Abstract

Quantum computing has recently exhibited great potential in predicting chemical properties for various applications in drug discovery, material design, and catalyst optimization. Progress has been made in simulating small molecules, such as LiH and hydrogen chains of up to 12 qubits, by using quantum algorithms such as variational quantum eigensolver (VQE). Yet, originating from the limitations of the size and the fidelity of near-term quantum hardware, the accurate simulation of large realistic molecules remains a challenge. Here, integrating an adaptive energy sorting strategy and a classical computational method—the density matrix embedding theory, which respectively reduces the circuit depth and the problem size, we present a means to circumvent the limitations and demonstrate the potential of near-term quantum computers toward solving real chemical problems. We numerically test the method for the hydrogenation reaction of C6H8 and the equilibrium geometry of the C18 molecule, using basis sets up to cc-pVDZ (at most 144 qubits). The simulation results show accuracies comparable to those of advanced quantum chemistry methods such as coupled-cluster or even full configuration interaction, while the number of qubits required is reduced by an order of magnitude (from 144 qubits to 16 qubits for the C18 molecule) compared to conventional VQE. Our work implies the possibility of solving industrial chemical problems on near-term quantum devices.

Quantum embedding simulation greatly enhanced the capability of near-term quantum computers on realistic chemical systems and reach accuracy comparable to advanced quantum chemistry methods.

1. Introduction

Various methods based on wave function theory, from the primary mean-field Hartree–Fock to high accuracy coupled-cluster and full configuration interaction methods, have been developed to simulate many-electron molecular systems.1,2 However, owing to the exponential wall,3 the exact treatment of those systems with more than a few dozens of orbitals remains intractable for classical computers, hindering further investigations on large realistic chemical systems. Quantum computing is believed to be a promising approach to overcome the exponential wall in quantum chemistry simulation,4–6 which may potentially boost relevant fields such as material design and drug discovery. Despite the great potential, fault-tolerant simulation of realistic molecules is still far beyond the current reach.7–11 In the present noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era,12 variational quantum eigensolver (VQE), as one of the most popular quantum-classical algorithms,4,13–27 has been exploited to experimentally study molecules from H2 (2 qubits),14 BeH2 (6 qubits),15 H2O (8 qubits),26 to H12 (12 qubits)16 and isomers of benzyne C6H4 (4 qubits).28,29 Meanwhile, the largest scale numerical molecular VQE simulation is C2H4 (28 qubits).27 The simulation of even large molecular systems might be realized in the future with the recently developed fermionic quantum emulator,30 which utilizes the particle number and spin symmetry along with custom evolution routines for Hamiltonians to reduce the memory requirement.

However, realistic chemical systems with an appropriate basis set generally involve hundreds or thousands of qubits, and whether VQE with NISQ hardware is capable of solving any practically meaningful chemistry problems remains open. The main challenge owes to limitations on the size (the number of qubits) and the fidelity (the simulation accuracy) of NISQ hardware.12,17,18,21 Specifically, it is yet hard to scale up the hardware size, while maintaining or even increasing the gate fidelity. Experimentally, when VQE is directly implemented on more than hundreds of qubits, the number of gates needed might become too large so that errors would accumulate drastically and error mitigation would require too many measurements to reach the desired chemical accuracy.

Adaptive and hybrid classical-quantum computational methods provide more economical ways to potentially bypass the conundrum. On the one hand, adaptive VQE algorithms31–44 can greatly reduce the circuit depth and hence alleviate the limitation on the gate fidelity. On the other hand, noticing the fact that most quantum many-body systems have mixed strong and weak correlation, we only need to solve the strongly correlated degrees of freedom using quantum computing and calculate the remaining part at a mean-field level using classical computational methods. Along this line, several hybrid methods have been proposed by exploiting different classical methods,45–47 such as density matrix embedding theory,48–51 dynamical mean field theory,52–54 density functional theory embedding,55 quantum defect embedding theory,56,57 tensor networks,23,58 and perturbation theory.59 Density matrix embedding is one of the representative embedding methods that have been theoretically and experimentally developed in several studies,6,48–51,60–67 yet the practical realization toward realistic chemical systems remains a significant technical challenge.

In this work, we integrate the adaptive energy sorting strategy68 and density matrix embedding theory,48–51,62 and provide a systematic way with multiscale descriptions of quantum systems toward practical quantum simulation of realistic molecules. We numerically study chemical systems with strong electron–electron correlation with specific geometries, including the homogeneous stretching of the H10 chain, the reaction energy profile for the hydrogenation of C6H8 and the potential energy curve of the C18 molecule.69 While using a much smaller number of qubits (from 144 qubits to 16 qubits for the C18 molecule) and a much shallower quantum circuit, our method can still reach high accuracy comparable to coupled cluster or even full configuration interaction calculations. Our work reveals the possibility of studying realistic chemical processes on near-term quantum devices.

2. Framework

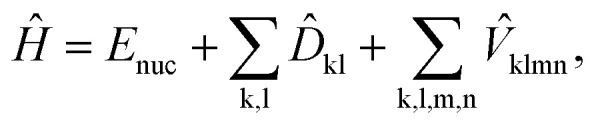

The generic Hamiltonian of a quantum chemical system under the Born–Oppenheimer approximation4 in the second-quantized form can be expressed as

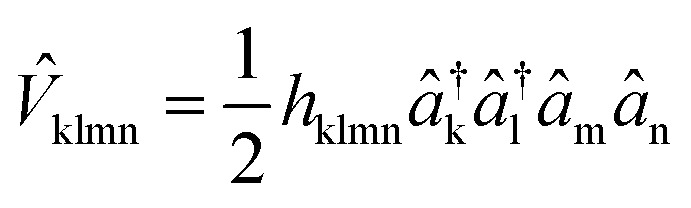

|

1 |

where Enuc is the scalar nuclear repulsion energy, D̂kl = dklâ†kâl and  are the one and two-body interaction operators, respectively, âp (â†p) is the fermionic annihilation (creation) operator to the pth orbital, and {dkl} and {hklmn} are the corresponding one- and two-electron integrals calculated with classical computers, respectively. Here, we denote the spin-orbitals of the molecule as k, l, m, and n. Variational quantum eigensolvers (VQEs) can be used to find a ground state of the Hamiltonian in eqn (1).4,17 The key idea is that the parametrized quantum state Ψ(

) is prepared and measured on a quantum computer, while the parameters are updated using a classical optimizer on a classical computer. The ground state can be found by minimizing the total energy with respect to the variational parameters

, following the variational principle, E = min

〈Ψ(

)|Ĥ|Ψ(

)〉.

are the one and two-body interaction operators, respectively, âp (â†p) is the fermionic annihilation (creation) operator to the pth orbital, and {dkl} and {hklmn} are the corresponding one- and two-electron integrals calculated with classical computers, respectively. Here, we denote the spin-orbitals of the molecule as k, l, m, and n. Variational quantum eigensolvers (VQEs) can be used to find a ground state of the Hamiltonian in eqn (1).4,17 The key idea is that the parametrized quantum state Ψ(

) is prepared and measured on a quantum computer, while the parameters are updated using a classical optimizer on a classical computer. The ground state can be found by minimizing the total energy with respect to the variational parameters

, following the variational principle, E = min

〈Ψ(

)|Ĥ|Ψ(

)〉.

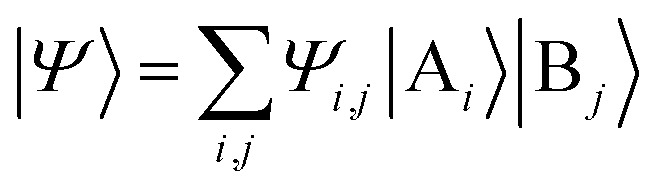

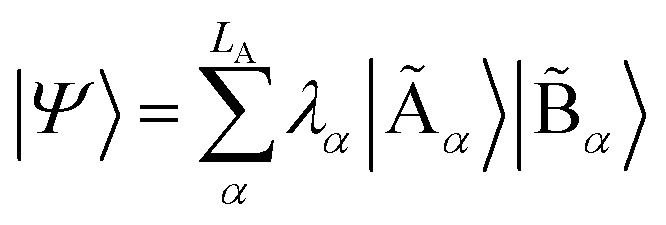

The above quantum algorithm entails a number of qubits no smaller than the system size, making it inaccessible to large realistic molecular systems. Here, we introduce the quantum embedding approach, a powerful classical method originally proposed by Knizia et al.,48 to reduce the required quantum resources. We consider to divide the total Hilbert space  of the quantum system into two parts, the fragment A with LA bases {|Ai〉} and the environment B with LB bases {|Bj〉}, respectively. The full quantum state in the {|Ai〉|Bj〉} basis can be represented by

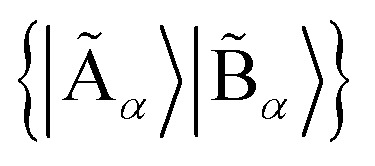

of the quantum system into two parts, the fragment A with LA bases {|Ai〉} and the environment B with LB bases {|Bj〉}, respectively. The full quantum state in the {|Ai〉|Bj〉} basis can be represented by  with dimensions LA × LB. However, this can be largely reduced by considering the entanglement between the two parts. Specifically, the quantum state |Ψ〉 can be decomposed into a rotated basis

with dimensions LA × LB. However, this can be largely reduced by considering the entanglement between the two parts. Specifically, the quantum state |Ψ〉 can be decomposed into a rotated basis  as

as  , corresponding to Schmidt decomposition of bipartite states. After the decomposition, we can split the environment into at most LA bath states that are entangled with the fragment and purely disentangled ones. We could thus construct the embedding Hamiltonian by projecting the full Hamiltonian

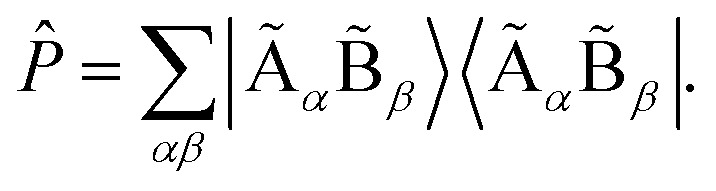

, corresponding to Schmidt decomposition of bipartite states. After the decomposition, we can split the environment into at most LA bath states that are entangled with the fragment and purely disentangled ones. We could thus construct the embedding Hamiltonian by projecting the full Hamiltonian  into the space spanned by the basis of the fragment and bath as Ĥemb = P̂ĤP̂ with the projector P̂ defined as

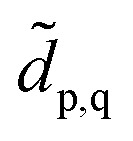

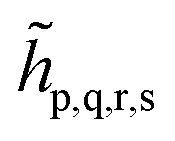

into the space spanned by the basis of the fragment and bath as Ĥemb = P̂ĤP̂ with the projector P̂ defined as  We note that the embedding Hamiltonian can be represented in the rotated spin-orbitals p, q, r, s with renormalized coefficients

We note that the embedding Hamiltonian can be represented in the rotated spin-orbitals p, q, r, s with renormalized coefficients  and

and  (see the ESI†), and admits the second-quantized form as that in eqn (1).

(see the ESI†), and admits the second-quantized form as that in eqn (1).

We can find that if |Ψ〉 is the ground state of a Hamiltonian Ĥ, it must also be the ground state of Ĥemb. This indicates that the solution of a small embedded system is the exact equivalent to that of the full system,50 with the dimensions of the embedded system reduced to LA × LA. In principle, the construction of P̂ requires the exact ground state of the full system |Ψ〉, which makes it unrealistic from theory. However, since we are interested in the ground state properties (for instance, the energy, which is a local density), we can consider to match the density or density matrix of the embedding Hamiltonian and the full Hamiltonian at a self-consistency level. More specifically, we consider a set of coupled eigenvalue equations

| Ĥmf|Φ〉 = Emf|Φ〉, Ĥemb|Ψ〉 = Eemb|Ψ〉, | 2 |

which describe a low-level mean-field system and a high-level interacting embedding system, respectively. Here, the mean-field Hamiltonian can be constructed provided the correlation potential Ĉ as Ĥmf = Ĥ0mf + Ĉ, and we can efficiently obtain the low-level wavefunction |Φ〉 and hence the one-body reduced density matrix 1Dkl = 〈â†kâl〉. Here Ĥmf0 is the original mean-field Hamiltonian constructed directly from Ĥ and 1Dkl. Given the solution of the eigenvalue equations in eqn (2), we can also obtain the reduced density matrix of the embedded system. At a self-consistency level, we can match the reduced density matrices of the multilevel systems by adjusting the correlation potential Ĉ in the mean-field Hamiltonian Ĥmf, and we obtain a guess for the ground state solution at convergence.

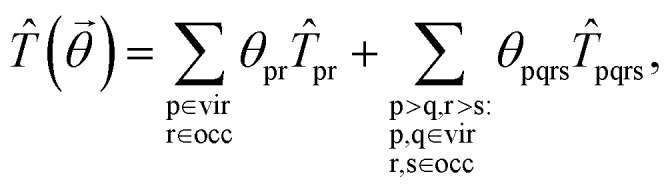

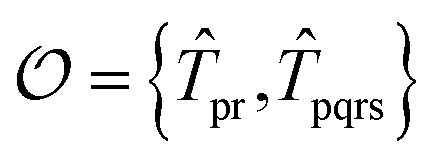

Next, we discuss how to get the solution of the high-level embedding Hamiltonian using variational quantum eigensolvers. The key ingredient in VQE is to design an appropriate circuit ansatz to approximate the unknown ground state of the chemical system. Here, we use the unitary coupled-cluster (UCC) ansatz,70–72 which effectively considers the excitations and de-excitations above a reference state. The UCC ansatz is defined as |Ψ〉 = exp(T̂ − T̂†)|Ψ0〉, where |Ψ0〉 is chosen as the Hartree–Fock ground state represented in the basis of the embedded system, and T̂ is the cluster operator. The cluster operator truncated at single- and double-excitations has the form where the one- and two-body terms are defined as T̂pr = â†pâr and T̂pqrs = â†pâ†qârâs, respectively. Then, we can get the high-level wavefunction by optimizing the energy of the embedded system, E = minθ〈Ψ(

)|Ĥemb|Ψ(

)〉, and thus can obtain the reduced density matrices 1D. Matching the reduced density matrices with those of the mean-field system forms a self-consistency loop until convergence.

where the one- and two-body terms are defined as T̂pr = â†pâr and T̂pqrs = â†pâ†qârâs, respectively. Then, we can get the high-level wavefunction by optimizing the energy of the embedded system, E = minθ〈Ψ(

)|Ĥemb|Ψ(

)〉, and thus can obtain the reduced density matrices 1D. Matching the reduced density matrices with those of the mean-field system forms a self-consistency loop until convergence.

3. Implementation

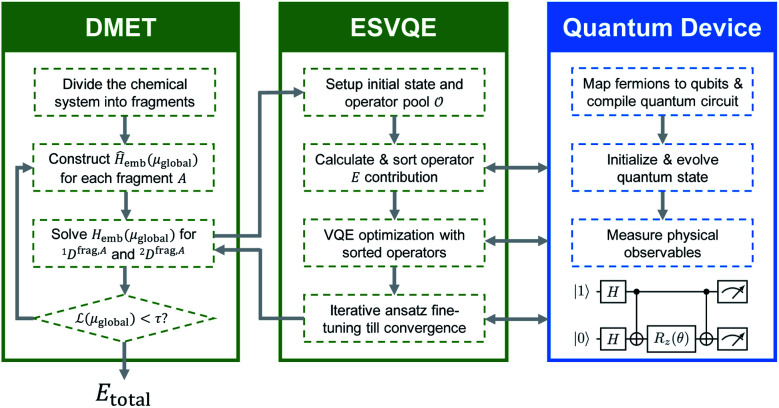

Here, we discuss the implementation of the quantum embedding theory in practice. In this work, we employ the energy sorting (ES) strategy68 to select only the dominant excitations in the original operator pool and construct a compact quantum circuit in VQE procedures. We term the algorithm DMET-ESVQE and an overall schematic flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. Our detailed algorithm can be found in the ESI.†

Fig. 1. The workflow for the DMET–ESVQE method. The chemical system is first decomposed into fragments. Then the effective embedding Hamiltonian Hemb(μglobal) in DMET iteration is solved by ESVQE. The ESVQE module utilizes quantum devices in the blue box to prepare quantum states and measure physical observables. Both DMET iteration and ESVQE parameter optimization are carried out on a classical computer, indicated by green boxes.

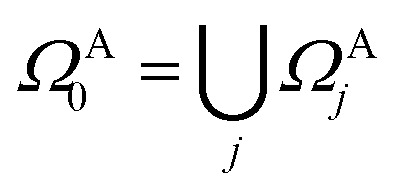

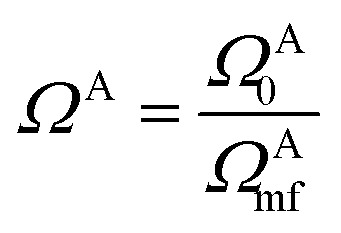

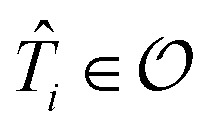

In practical molecular DMET implementation, we determine the fragment partition on the basis of atomic orbital interactions. The conventional partitioning based on clusters of atoms chooses the set of single-particle bases ΩA0 for fragment A as  , where ΩAj is the set of bases located on the jth atom of fragment A. Here, we define a set of inactive orbitals ΩAmf treated at the mean-field level and excluded from the DMET iteration, resulting in a reduced basis set

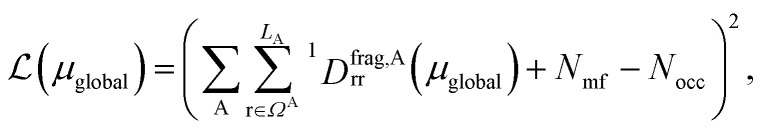

, where ΩAj is the set of bases located on the jth atom of fragment A. Here, we define a set of inactive orbitals ΩAmf treated at the mean-field level and excluded from the DMET iteration, resulting in a reduced basis set  . Note that ΩAmf could be an empty set. Compared to ΩA0, ΩA can more effectively capture the entanglement between the orbitals and is more compact for the VQE procedure. During the DMET optimization, we introduce a global chemical potential μglobal to preserve the total number of electrons Nocc, and the DMET cost function

. Note that ΩAmf could be an empty set. Compared to ΩA0, ΩA can more effectively capture the entanglement between the orbitals and is more compact for the VQE procedure. During the DMET optimization, we introduce a global chemical potential μglobal to preserve the total number of electrons Nocc, and the DMET cost function  can now be written as

can now be written as

|

3 |

where  is the number of electrons in the inactive orbitals obtained at the mean-field level, termed the single-shot embedding.50 We note that 1Dmfrr is invariant during single-shot embedding iteration, and thus Nmf is not a function of μglobal. This feature distinguishes the approach from simply adopting an active space high-level solver. More details can be found in the ESI.†

is the number of electrons in the inactive orbitals obtained at the mean-field level, termed the single-shot embedding.50 We note that 1Dmfrr is invariant during single-shot embedding iteration, and thus Nmf is not a function of μglobal. This feature distinguishes the approach from simply adopting an active space high-level solver. More details can be found in the ESI.†

For the ESVQE part, an efficient ansatz for each of the fragment is constructed by selecting dominant excitation operators in the operator pool  . Here, the importance of the operator

. Here, the importance of the operator  is evaluated by the magnitude of energy difference between the reference state as ΔEi = Ei − Eref with Ei = minθi〈Ψref|e−θi(T̂i − T̂†i)Ĥeθi(T̂i − T̂†i)|Ψref〉 and Eref = 〈Ψref|Ĥ|Ψref〉. The operators with contributions above a threshold |ΔEi| > ε are picked out and used to perform the VQE optimization. Extra fine-tuning can be performed by iteratively adding more operators to the ansatz until the energy difference E(k−1) − E(k) between the (k − 1)th and the kth iteration is smaller than a certain convergence criterion. In this work we skip this step for simplicity. More details can be found in the ESI.†

is evaluated by the magnitude of energy difference between the reference state as ΔEi = Ei − Eref with Ei = minθi〈Ψref|e−θi(T̂i − T̂†i)Ĥeθi(T̂i − T̂†i)|Ψref〉 and Eref = 〈Ψref|Ĥ|Ψref〉. The operators with contributions above a threshold |ΔEi| > ε are picked out and used to perform the VQE optimization. Extra fine-tuning can be performed by iteratively adding more operators to the ansatz until the energy difference E(k−1) − E(k) between the (k − 1)th and the kth iteration is smaller than a certain convergence criterion. In this work we skip this step for simplicity. More details can be found in the ESI.†

4. Results and discussion

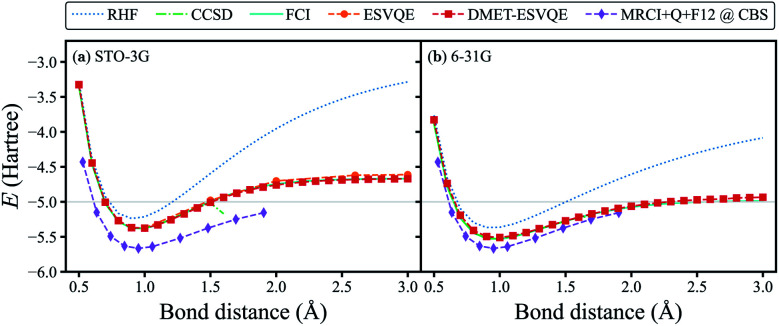

To benchmark our algorithm, we first show the simulated potential energy curve for the homogeneous stretching of a hydrogen chain composed of 10 atoms in Fig. 2, a benchmark platform for advanced many-body computation methods.73,74 Classical quantum chemistry calculations are performed with the PySCF package75 (the same hereinafter unless otherwise stated). In our DMET-ESVQE simulation, we consider each hydrogen atom as a fragment  . With both STO-3G and 6-31G basis sets, DMET–ESVQE is in excellent agreement with FCI results. The coupled-cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) method performs well near the equilibrium bond distance; however, in the dissociation limit (bond distance > 1.7 Å) its calculation fails to converge.74 For the STO-3G basis set, conventional ESVQE with 20 qubits is performed for a limited number of bond distances due to the prohibitive computational cost. Surprisingly, in the dissociation limit, DMET–ESVQE is more accurate than conventional ESVQE despite the drastic reduction of the number of qubits. This counter-intuitive outcome, along with a detailed analysis of the errors, is discussed in the ESI.† To evaluate the error introduced by the incomplete basis set, we include results from the MRCI + Q + F12 method in the complete basis set (CBS) limit,74 which can be considered as the true ground state energy for the potential energy curve of H10. By comparing Fig. 2(a) and (b), we find that using a larger basis set brings the potential energy curve produced by DMET–ESVQE much closer to the MRCI + Q + F12@CBS reference curve and the exact dissociation limit, which is only made possible by the DMET framework.

. With both STO-3G and 6-31G basis sets, DMET–ESVQE is in excellent agreement with FCI results. The coupled-cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) method performs well near the equilibrium bond distance; however, in the dissociation limit (bond distance > 1.7 Å) its calculation fails to converge.74 For the STO-3G basis set, conventional ESVQE with 20 qubits is performed for a limited number of bond distances due to the prohibitive computational cost. Surprisingly, in the dissociation limit, DMET–ESVQE is more accurate than conventional ESVQE despite the drastic reduction of the number of qubits. This counter-intuitive outcome, along with a detailed analysis of the errors, is discussed in the ESI.† To evaluate the error introduced by the incomplete basis set, we include results from the MRCI + Q + F12 method in the complete basis set (CBS) limit,74 which can be considered as the true ground state energy for the potential energy curve of H10. By comparing Fig. 2(a) and (b), we find that using a larger basis set brings the potential energy curve produced by DMET–ESVQE much closer to the MRCI + Q + F12@CBS reference curve and the exact dissociation limit, which is only made possible by the DMET framework.

Fig. 2. DMET–ESVQE simulated homogeneous stretching of an evenly spaced hydrogen chain composed of 10 atoms in (a) STO-3G and (b) 6-31G basis sets, in comparison with RHF, CCSD and FCI results. The MRCI + Q + F12@CBS results in both panels can be considered as the exact reference in the complete basis set (CBS) limit.74 For the STO-3G basis set, we also show the results obtained by conventional ESVQE. The grey horizontal line indicates the exact dissociation limit composed of non-interacting hydrogen atoms.

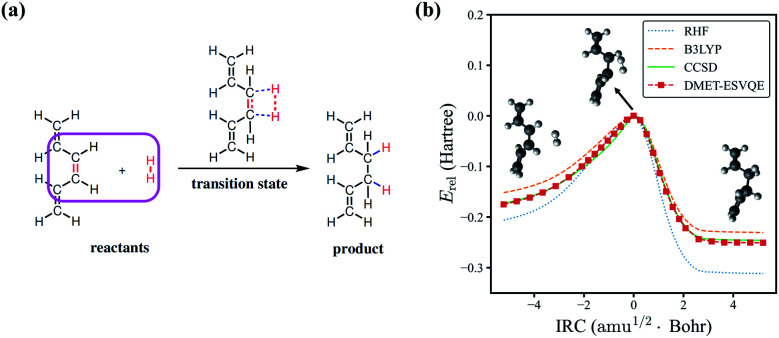

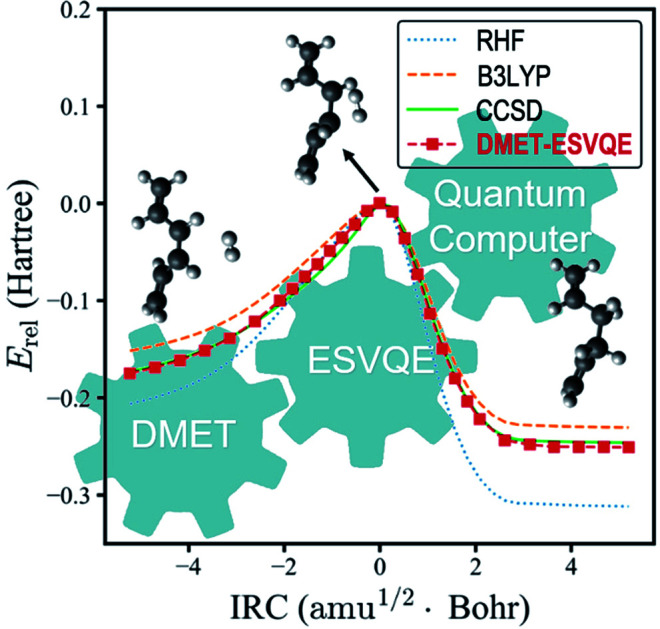

Next, we study the energy profile for the addition reaction between C6H8 and H2 in the gas phase, which is a simplified model for the addition of hydrogen to conjugated hydrocarbons, an essential step for many organic synthesis routes.76–78 A schematic diagram of the addition reaction is depicted in Fig. 3(a). A large fraction of the molecule is involved in conjugated π bonds, which poses a challenge for quantum embedding theories. Besides, the transition state, defined as the first order saddle point in the potential energy surface, is known to be difficult for electronic structure methods. In DMET–ESVQE simulation, each atom in the magenta box is considered as a single fragment with the 1s orbitals for carbon atoms frozen. The transition state and the intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRCs)79 for the reaction are determined by density functional theory (DFT) with the hybrid functional B3LYP under an STO-3G basis set using the Gaussian 09 package.80 In Fig. 3(b), we plot the relative energy Erel = E − ETS along with the IRC, where ETS is the transition state energy. The absolute value of ETS can be found in the ESI.† In agreement with the common quantum chemistry perception, restricted Hartree–Fock (RHF) overestimates the reaction barrier, while B3LYP (DFT) underestimates the reaction barrier. On the other hand, the energy profile generated by DMET–ESVQE is in remarkable agreement with the highly accurate and time-consuming CCSD method. We note that using a basis set larger than STO-3G is essential for a more realistic description of the reaction.

Fig. 3. The potential energy curve for the hydrogenation reaction of C6H8 with H2. (a) A schematic view for the hydrogenation reaction of C6H8 with H2. Each atom in the magenta box is considered as a single fragment. (b) Comparison of the energies obtained with RHF, B3LYP, CCSD and DMET-ESVQE along the IRC of the reaction. The relative energy Erel is E − ETS where ETS is the transition state energy. Note that ETS is different for different methods.

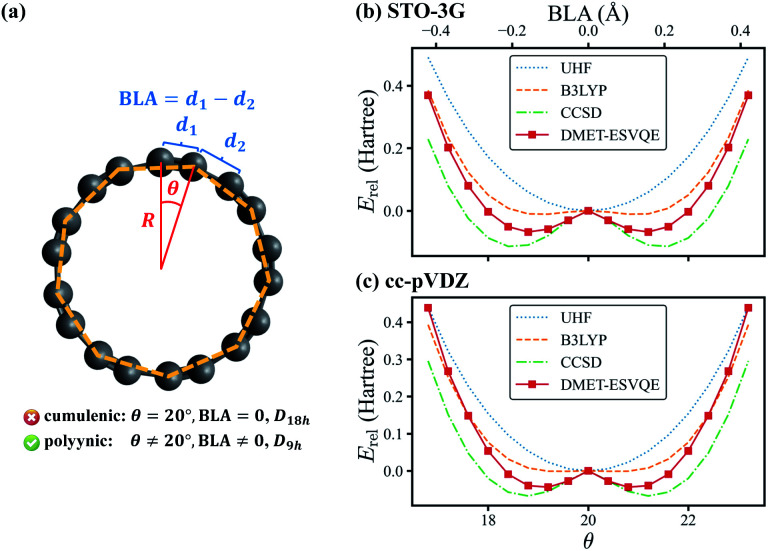

The last system studied is the C18 molecule, a novel carbon allotrope with many potential applications such as molecular devices due to its exotic electronic structure.81–84 Before its experimental identification,69 the equilibrium geometry of the molecule is under heated debate: DFT and perturbation theory (MP2) often conclude a D18h cumulenic structure, yet high-level CCSD calculations indicate that a bond-length and bond-angle alternated polyynic structure is more energetically favoured.85 In 2019, the polyynic structure is confirmed unambiguously via experimental synthesis of the molecule.69 In this work we investigate a series of geometries of the C18 molecule, as shown in Fig. 4(a), to determine the molecule's equilibrium geometry. These geometries are generated by relatively rotating two interleaving C9 regular nonagons by an angle of θ ∈ [0, 40°], with all carbon atoms located on the same plane. We define d1 and d2 as the lengths of the two sets of C–C bonds in the molecule and the bond length alternation (BLA) as d1 − d2. The θ = 20° geometry is known as the cumulenic structure, while for other cases the geometries with D9h symmetry are called the polyynic structure. The radius R of the regular nonagon is determined to be 3.824 Å via geometry optimization at the CCSD/STO-3G level using the Gaussian 09 package.80

Fig. 4. (a) A schematic diagram of the C18 molecule. θ is the angle between the two interleaving C9 nonagons, one of which is indicated with orange dashed lines. R is the radius of the regular nonagons. d1 and d2 are the two sets of C–C bond lengths, respectively. (b) and (c) Comparison of the energies obtained with UHF, B3LYP, CCSD and DMET-ESVQE for the potential energy curve of the C18 molecule within (b) STO-3G and (c) cc-pVDZ basis sets. The relative energy Erel is defined as E − Ecumu where Ecumu is the energy for the θ = 20° cumulenic structure. The DMET-ESVQE results suggest that the bond-length alternating structure is favoured, which agrees with experimental observation.

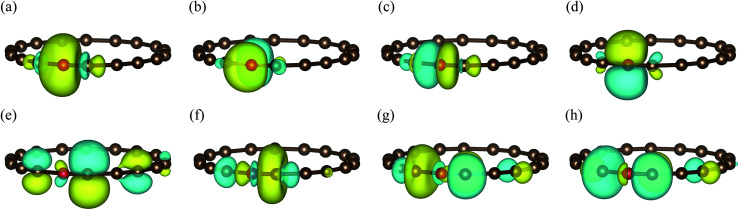

In Fig. 4(b), we present the potential energy curve in the physically intriguing region θ ∈ [16.8°, 23.2°] within the STO-3G basis set. The relative energy Erel is Erel = E − Ecumu, where Ecumu is the energy for the θ = 20° cumulenic structure. The absolute value of Ecumu can be found in the ESI.† For this pathological system, RHF is known to suffer from the convergence problem84 and thus the unrestricted Hartree–Fock (UHF) results are shown. However, the UHF energy curve is qualitatively incorrect in that it anticipates the cumulenic structure to be more stable. The representative DFT method B3LYP predicts a rather flat potential energy curve around θ = 20° and the polyynic structure is slightly favoured by 11 mH compared to that of the cumulenic structure. Because it is well documented that the full degree of freedom optimization at the B3LYP level yields a cumulenic structure,84–86 we believe the slight advantage of the polyynic structure shown in Fig. 4(b) is an artifact of the fixed R. In DMET-ESVQE simulation, we treat each carbon atom as a fragment with the 1s orbital frozen. As illustration, the orbitals of the fragment and the corresponding bath under the STO-3G basis set at the angle θ = 18° are shown in Fig. 5. The orbitals are generated by the PYSCF package and drawn by using VESTA software.87 Unlike UHF and B3LYP, DMET–ESVQE correctly reproduces the polyynic structure. We note that solving the ground state of the full molecule with conventional VQE requires 144 qubits under frozen core approximation, while for DMET–ESVQE 16 qubits are sufficient for a correlated treatment of the whole molecule. Fig. 4(c) shows the results with Dunning's correlation-consistent basis set cc-pVDZ.88 In DMET-ESVQE simulation, the 2s and 2p basis orbitals for each carbon atom are considered as a single fragment and thus the effect of high angular momentum orbitals is treated at the mean-field level. The general trends reflected by Fig. 4(b) and (c) are consistent and only CCSD and DMET–ESVQE are able to produce the correct equilibrium geometry.

Fig. 5. The fragment and bath orbitals of the C18 molecule under the STO-3G basis set at the angle θ = 18°. (a)–(d) Fragment orbitals corresponding to localized 2s and 2p orbitals in a single carbon atom (red ball). (e)–(h) Bath orbitals obtained by Schmidt decomposition.

5. Simulation with noise

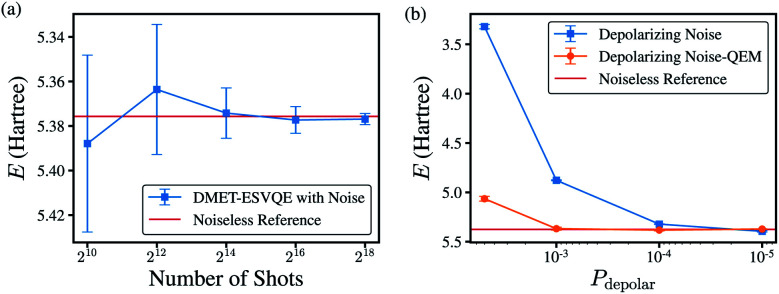

To evaluate the algorithm on real noisy quantum devices, we performed noisy simulations on the H10 molecule with the STO-3G basis set using the QASM simulator from the Qiskit toolkit.89 As shown in Fig. 6(a), we first evaluate the shot-noise effect with the number of shots ranging from 210 to 218 without extra gate noise. DMET-ESVQE exhibits fast convergence versus the repetitions of the quantum circuit. The difference between the reference values and the simulated result is no more than 15 mH. When the number of shots is increased to 214, the standard deviation also decreases to around 1 mH.

Fig. 6. (a) DMET–VQE energy vs. number of shots for the H10 molecule without introducing gate noise. The bond distance is set to 1.0 Å. (b) DMET–VQE energy vs. depolarizing probability with 216 shots. The red line is the calculated DMET–ESVQE energy using the ideal solver.

We next consider depolarizing noise and apply zero-noise extrapolation based on linear fitting using the Mitiq package90 to mitigate noise, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The quantum observable is measured at noise-scaled quantum circuits by unitary folding and extrapolated to the zero-noise limit by linear fitting. The scaling factors are 1.00, 1.25 and 1.50 in our calculations. The calculated energy by naively applied DMET–ESVQE fails when encountering large noise (depolarizing probability, Pdepolar ≥ 5 × 10−3). For smaller Pdepolar, the deviation becomes smaller to tens of mH. After quantum error mitigation, the deviation from the reference value decreases from 2.065 Hartree to 0.249 Hartree for Pdepolar = 5 × 10−3. For calculations with smaller Pdepolar, after QEM the deviation is further reduced to less than 10 mH. DMET–ESVQE calculations show fast convergence with the number of shots and robustness to noise.

With the quantum error mitigation method, we can achieve desired simulation accuracy with respect to the reference value computed from an ideal simulator. Our result indicates a promising application on real quantum devices.

6. Quantum resource reduction

For the systems investigated in this work, DMET–ESVQE is able to reduce the number of qubits by about an order of magnitude and the number of excitation parameters by several orders of magnitude, and thus effectively reduces the resource requirements for quantum devices. In Table 1 we show the reduction of the number of qubits and excitation parameters by DMET and ESVQE. For H10 the bond distance is set to 3 Å while for C6H8 + H2 and C18 we use the transition state geometry and the cumulenic geometry respectively. When counting the total number of electrons and spin-orbitals, for C6H8 + H2 and C18 (STO-3G), we have frozen the 1s orbitals, and for C18 (cc-pVDZ) we have also frozen the 3s, 3p and 3d orbitals, in order for a fair comparison with DMET. For conventional VQE (cVQE), the number of qubits required are the same as the number of spin-orbitals, assuming Jordan–Wigner transformation. In DMET schemes, the number of qubits for the quantum solver is determined by the maximum number of orbitals in each of the fragment. Suppose in fragment A there are LA spin orbitals and accordingly there are LA spin orbitals for the bath, then under fermion-to-qubit mapping (such as Jordan–Wigner transformation) 2LA qubits are required for the quantum solver. The number of excitation parameters is computed assuming that the total spin of the molecule is zero. Suppose there are nocc occupied spatial-orbitals and nvir unoccupied spatial-orbitals, the total number of independent excitation amplitudes is:

| Nex = noccnvir + noccnvir(noccnvir + 1)/2 | 4 |

where the first term and the second term correspond to single- and double-excitations respectively. For the cumulenic structure of C18 DMET and ESVQE together realize a 19 576-fold parameter number reduction. We expect the effect of DMET to be more prominent for more complex chemical systems. We note here that each parameter is associated with a generator T̂i − T̂†i, which then transformed into the qubit type Pauli operator. The exponential of the generator will decompose into a sequence of single-qubit gates and two-qubit gates after the Trotter decomposition. We refer readers to find more details about the decomposed quantum gate and depth for the corresponding single-excitation and double-excitation in Sec. II in the ESI.†

The reduction of the number of qubits and excitation parameters by DMET and ESVQE. cVQE represents conventional VQE without the energy sorting (ES) strategy.

| System | Basis | Electrons | Spin–orbitals | Method | Qubits | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H10 | STO-3G | 10 | 20 | cVQE | 20 | 350 |

| DMET–cVQE | 4 | 2 | ||||

| DMET–ESVQE | 4 | 1 | ||||

| H10 | 6-31G | 10 | 40 | cVQE | 40 | 2925 |

| DMET–cVQE | 8 | 14 | ||||

| DMET–ESVQE | 8 | 10 | ||||

| C6H8 + H2 | STO-3G | 34 | 68 | cVQE | 68 | 42 194 |

| DMET–cVQE | 16 | 152 | ||||

| DMET–ESVQE | 16 | 105 | ||||

| C18 | STO-3G | 72 | 144 | cVQE | 144 | 841 752 |

| DMET–cVQE | 16 | 152 | ||||

| DMET–ESVQE | 16 | 44 | ||||

| C18 | cc-pVDZ | 72 | 144 | cVQE | 144 | 841 752 |

| DMET–cVQE | 16 | 152 | ||||

| DMET–ESVQE | 16 | 43 |

7. Conclusion

In this work, we propose to integrate ESVQE with DMET for the study of realistic chemical problems. For benchmarking purposes, the typical model system H10 is first tested with the STO-3G basis set, and we find that DMET–ESVQE reaches near FCI accuracy. DMET also enables ESVQE simulation of H10 with the 6-31G basis set, producing a potential energy curve much closer to the reference result in the complete basis set limit. The study of the hydrogenation reaction between C6H8 and H2 shows that the accuracy of DMET–ESVQE is comparable to that of CCSD, while the number of qubits required for VQE is reduced from 68 qubits to 16 qubits. The last case studied in this work is the equilibrium geometry of the C18 molecule and it is found that DMET–ESVQE correctly predicts the experimentally observed polyynic structure with a significant reduction of the quantum resource, from 144 qubits to 16 qubits. Our results suggest that the DMET embedding scheme can effectively extend the simulation scale of the state-of-the-art NISQ quantum computers.

To further expand the capability of quantum embedding simulation, the effort could be divided into two directions: improved embedding scheme and high-level quantum solvers. For the embedding scheme part, the efforts could be further divided into three sub-directions. One may need to develop more effective partition schemes to capture the correlation between the fragment and bath. Or, one may apply the self-consistent fitting feature with a correlation potential to the DMET iteration and try other cost functions, respectively.50 Particularly, one may consider to speed up the convergence through projected DMET60 and enhance the robustness and efficiency of DMET via semidefinite programming and local correlation potential fitting.63 Finally, one may consider the bootstrap embedding scheme, which has been tested on larger molecule systems to achieve better accuracy and faster convergence.91–93 For the high-level quantum solvers part, there are at least several directions that one can pursue. For the ESVQE, one may reduce the energy threshold ε to increase the operator pool size selected for the VQE iteration, thus further increasing the accuracy. Apart from the energy sorting scheme, it is worth trying other schemes such as k-UpCCGSD31 to prepare trial states in the high-level quantum solver. One may also try more efficient optimizers or more advanced quantum algorithms to find the ground state.94–99 When implementing the high-level quantum solver on real quantum systems, one may explore quantum error mitigation methods to improve the accuracy of the measurement results.100–105 For more efficient simulation of larger molecule systems, advanced measurement schemes can be used to reduce the measurement cost, such as (derandomized) classical shadows or Pauli grouping methods to reduce the measurement overhead.13,15,106–108

The synergistic development of quantum embedding theory, high-level quantum solvers and quantum devices provides a great chance of solving strongly correlated chemical systems in future. For example, one of the holy grails for quantum chemistry is the electronic structure of the iron–sulfur clusters of nitrogenase,7,109,110 which contains eight transition metal atoms and exhibits strong correlation. Within the polarized triple-zeta basis set, it requires about 50 basis functions to describe each metal atom. If, in the future, 200 qubits with a sufficiently long coherence time and high gate fidelity are available, the clusters can be divided into fragments consisting of individual transition metal atoms, such that the fragment + bath problem of embedded transition metal atoms can be solved accurately using efficient VQE algorithms. The successful implementation of the proposed protocol may elucidate the complicated interaction of transition metal atoms and push the boundary of theoretical chemistry.

Data availability

Data for this paper are available at Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6544996.

Author contributions

D. Lv conceived the project. D. Lv, W. Li and Z. Huang implemented the DMET–ESVQE algorithm. W. Li collected the numerical data with the help from Z. Shuai. W. Li, Z. Huang, C. Cao, Y. Huang, J. Sun, X. Yuan, and D. Lv wrote the manuscript. J. Sun, X. Yuan and X. Sun helped analyze the data.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Jiajun Ren, Chong Sun, Hongzhou Ye, Hung Q. Pham, He Ma and Xuelan Wen, Nan Sheng, Zhihao Cui, Zhen Huang, and Ji Chen for helpful discussions and Hang Li for support and guidance.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc01492k

Notes and references

- Szabo A. and Ostlund N. S., Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory, Courier Corporation, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Levine I. N., Busch D. H. and Shull H., Quantum Chemistry, Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2009, vol. 6 [Google Scholar]

- Kohn W. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999;71:1253–1266. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.71.1253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle S. Endo S. Aspuru-Guzik A. Benjamin S. C. Yuan X. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020;92:015003. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.92.015003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aspuru-Guzik A. Dutoi A. D. Love P. J. Head-Gordon M. Science. 2005;309:1704–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.1113479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B. Bravyi S. Motta M. Chan G. K.-L. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:12685–12717. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiher M. Wiebe N. Svore K. M. Wecker D. Troyer M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:7555–7560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619152114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Li J. Dattani N. S. Umrigar C. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;150:024302. doi: 10.1063/1.5063376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. W. Gidney C. Motta M. McClean J. R. Babbush R. Quantum. 2019;3:208. doi: 10.22331/q-2019-12-02-208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Burg V. Low G. H. Häner T. Steiger D. S. Reiher M. Roetteler M. Troyer M. Phys. Rev. Res. 2021;3:033055. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.3.033055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Berry D. W. Gidney C. Huggins W. J. McClean J. R. Wiebe N. Babbush R. PRX Quantum. 2021;2:030305. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.030305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preskill J. Quantum. 2018;2:79. doi: 10.22331/q-2018-08-06-79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley P. J. Babbush R. Kivlichan I. D. Romero J. McClean J. R. Barends R. Kelly J. Roushan P. Tranter A. Ding N. et al. . Phys. Rev. X. 2016;6:031007. [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzo A. McClean J. Shadbolt P. Yung M.-H. Zhou X.-Q. Love P. J. Aspuru-Guzik A. O’brien J. L. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandala A. Mezzacapo A. Temme K. Takita M. Brink M. Chow J. M. Gambetta J. M. Nature. 2017;549:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature23879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arute F. Arya K. Babbush R. Bacon D. Bardin J. C. Barends R. Boixo S. Broughton M. Buckley B. B. Buell D. A. et al. . Science. 2020;369:1084–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo M. Arrasmith A. Babbush R. Benjamin S. C. Endo S. Fujii K. McClean J. R. Mitarai K. Yuan X. Cincio L. Coles P. J. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021;3:625–644. doi: 10.1038/s42254-021-00348-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti K. Cervera-Lierta A. Kyaw T. H. Haug T. Alperin-Lea S. Anand A. Degroote M. Heimonen H. Kottmann J. S. Menke T. Mok W.-K. Sim S. Kwek L.-C. Aspuru-Guzik A. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022;94:015004. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.94.015004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins W. J. McClean J. R. Rubin N. C. Jiang Z. Wiebe N. Whaley K. B. Babbush R. Npj Quantum Inf. 2021;7:23. doi: 10.1038/s41534-020-00341-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S. Sun J. Li Y. Benjamin S. C. Yuan X. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020;125:010501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S. Cai Z. Benjamin S. C. Yuan X. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021;90:032001. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.90.032001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel C. Maier C. Romero J. McClean J. Monz T. Shen H. Jurcevic P. Lanyon B. P. Love P. Babbush R. Aspuru-Guzik A. Blatt R. Roos C. F. Phys. Rev. X. 2018;8:031022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X. Sun J. Liu J. Zhao Q. Zhou Y. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;127:040501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii K. Mitarai K. Mizukami W. Nakagawa Y. O. PRX Quantum. 2022;3:010346. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.3.010346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Sun J. Endo S. Li Y. Benjamin S. C. Yuan X. Sci. Bull. 2021;66:2181–2188. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2021.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y. Chen J.-S. Pisenti N. C. Wright K. Delaney C. Maslov D. Brown K. R. Allen S. Amini J. M. Apisdorf J. et al. . Npj Quantum Inf. 2020;6:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41534-019-0235-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C. Hu J. Zhang W. Xu X. Chen D. Yu F. Li J. Hu H. Lv D. Yung M.-H. Phys. Rev. A. 2022;105:062452. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.105.062452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyn J.-N. Lykhin A. O. Smart S. E. Gagliardi L. Mazziotti D. A. J. Chem. Phys. 2021;155:244106. doi: 10.1063/5.0074842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart S. E. Boyn J.-N. Mazziotti D. A. Phys. Rev. A. 2022;105:022405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.105.022405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin N. C. Gunst K. White A. Freitag L. Throssell K. Chan G. K.-L. Babbush R. Shiozaki T. Quantum. 2021;5:568. doi: 10.22331/q-2021-10-27-568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Huggins W. J. Head-Gordon M. Whaley K. B. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018;15:311–324. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley H. R. Economou S. E. Barnes E. Mayhall N. J. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3007. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10988-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H. L. Shkolnikov V. Barron G. S. Grimsley H. R. Mayhall N. J. Barnes E. Economou S. E. PRX Quantum. 2021;2:020310. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.020310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinkin I. G. Yen T.-C. Genin S. N. Izmaylov A. F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018;14:6317–6326. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinkin I. G. Lang R. A. Genin S. N. Izmaylov A. F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:1055–1063. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.-J., Sun J., Yuan X. and Yung M.-H., 2020, arXiv:2011.05283

- Motta M. Ye E. McClean J. R. Li Z. Minnich A. J. Babbush R. Chan G. K.-L. npj Quantum Inf. 2021;7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41534-020-00339-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa Y. Kurashige Y. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:944–952. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottmann J. S. Aspuru-Guzik A. Phys. Rev. A. 2022;105:032449. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.105.032449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin N. C., Lee J. and Babbush R., 2021, arXiv:2109.05010

- Tkachenko N. V. Sud J. Zhang Y. Tretiak S. Anisimov P. M. Arrasmith A. T. Coles P. J. Cincio L. Dub P. A. PRX Quantum. 2021;2:020337. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.020337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins A. Motta M. Gujarati T. P. Bravyi S. Mezzacapo A. Hadfield C. Sheldon S. PRX Quantum. 2022;3:010309. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.3.010309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cincio L., Negre C. F., Czarnik P., Coles P., Anisimov P. M., Mniszewski S. M., Tretiak S. and Dub P. A., 2021, arXiv:2106.07619

- Kumar A., Asthana A., Masteran C., Valeev E. F., Zhang Y., Cincio L., Tretiak S. and Dub P. A., 2022, arXiv:2201.09852 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maier T. Jarrell M. Pruschke T. Hettler M. H. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005;77:1027. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.77.1027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q. Chan G. K.-L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:2705–2712. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotliar G. Savrasov S. Y. Haule K. Oudovenko V. S. Parcollet O. Marianetti C. A. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2006;78:865–951. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.78.865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knizia G. Chan G. K.-L. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:186404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.186404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knizia G. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:1428–1432. doi: 10.1021/ct301044e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters S. Jiménez-Hoyos C. A. Sun Q. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:2706–2719. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin N. C., 2016, arXiv:1610.06910

- Bauer B. Wecker D. Millis A. J. Hastings M. B. Troyer M. Phys. Rev. X. 2016;6:031045. [Google Scholar]

- Rungger I., Fitzpatrick N., Chen H., Alderete C. H., Apel H., Cowtan A., Patterson A., Ramo D. M., Zhu Y., Nguyen N. H., Grant E., Chretien S., Wossnig L., Linke N. M. and Duncan R., 2020, arXiv:1910.04735

- Chen H. Nusspickel M. Tilly J. Booth G. H. Phys. Rev. A. 2021;104:032405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.104.032405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmannek M. Barkoutsos P. K. Ollitrault P. J. Tavernelli I. J. Chem. Phys. 2021;154:114105. doi: 10.1063/5.0029536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. Govoni M. Galli G. npj Comput. Mater. 2020;6:85. doi: 10.1038/s41524-020-00353-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng N., Vorwerk C., Govoni M. and Galli G., Quantum Simulations of Material Properties on Quantum Computers, 2021, arXiv:2105.04736

- Orús R. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019;1:538–550. doi: 10.1038/s42254-019-0086-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Endo S., Lin H., Hayden P., Vedral V. and Yuan X., 2021, arXiv:2106.05938

- Wu X. Cui Z.-H. Tong Y. Lindsey M. Chan G. K.-L. Lin L. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;151:064108. doi: 10.1063/1.5108818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima Y. Coons M. P. Nam Y. Lloyd E. Matsuura S. Garza A. J. Johri S. Huntington L. Senicourt V. Maksymov A. O. Jason H. V. Nguyen. Jungsang Kim. Nima Alidoust. Arman Zaribafiyan. Takeshi Yamazaki. Commun. Phys. 2021;4:245. doi: 10.1038/s42005-021-00751-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly J. Sriluckshmy P. V. Patel A. Fontana E. Rungger I. Grant E. Anderson R. Tennyson J. Booth G. H. Phys. Rev. Research. 2021;3:033230. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.3.033230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Lindsey M. Zhou T. Tong Y. Lin L. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;102:085123. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.102.085123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z.-H. Zhu T. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:119–129. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertitta E. Booth G. H. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;151:014115. doi: 10.1063/1.5100290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X. Graham D. S. Chulhai D. V. Goodpaster J. D. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:385–398. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C. Ray U. Cui Z.-H. Stoudenmire M. Ferrero M. Chan G. K.-L. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;101:075131. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.075131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Cao C., Xu X., Li Z., Lv D. and Yung M.-H., 2021, arXiv:2106.15210

- Kaiser K. Scriven L. M. Schulz F. Gawel P. Gross L. Anderson H. L. Science. 2019;365:1299–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.aay1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutzelnigg W. J. Chem. Phys. 1982;77:3081–3097. doi: 10.1063/1.444231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R. J. Kucharski S. A. Noga J. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;155:133–140. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(89)87372-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taube A. G. Bartlett R. J. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2006;106:3393–3401. doi: 10.1002/qua.21198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hachmann J. Cardoen W. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:144101. doi: 10.1063/1.2345196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M. Ceperley D. M. Chan G. K.-L. Gomez J. A. Gull E. Guo S. Jiménez-Hoyos C. A. Lan T. N. Li J. Ma F. Millis A. J. Prokof’ev N. V. Ray U. Scuseria G. E. Sorella S. Stoudenmire E. M. Sun Q. Tupitsyn I. S. White S. R. Zgid D. Zhang S. Phys. Rev. X. 2017;7:031059. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q. Zhang X. Banerjee S. Bao P. Barbry M. Blunt N. S. Bogdanov N. A. Booth G. H. Chen J. Cui Z.-H. Eriksen J. J. Gao Y. Guo S. Hermann J. Hermes M. R. Koh K. Koval P. Lehtola S. Li Z. Liu J. Mardirossian N. McClain J. D. Motta M. Mussard B. Pham H. Q. Pulkin A. Purwanto W. Robinson P. J. Ronca E. Sayfutyarova E. R. Scheurer M. Schurkus H. F. Smith J. E. T. Sun C. Sun S.-N. Upadhyay S. Wagner L. K. Wang X. White A. Whitfield J. D. Williamson M. J. Wouters S. Yang J. Yu J. M. Zhu T. Berkelbach T. C. Sharma S. Sokolov A. Y. Chan G. K.-L. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;153:024109. doi: 10.1063/5.0006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N. S. Dullaghan E. M. Finlay B. B. Gong H. Reiner N. E. Jon Paul Selvam J. Thorson L. M. Campbell S. Vitko N. Richardson A. R. Zoraghi R. Young R. N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:1708–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y. Chen Z. Jing Y. Rong Y. Facchetti A. Yao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4956–4959. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawski W. Hurej K. Skonieczny J. Pawlicki M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:10946–10950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201904819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981;14:363–368. doi: 10.1021/ar00072a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A. V., Bloino J., Janesko B. G., Gomperts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H. P., Ortiz J. V., Izmaylov A. F., Sonnenberg J. L., Williams-Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Ranasinghe D., Zakrzewski V. G., Gao J., Rega N., Zheng G., Liang W., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Throssell K., Jr. J. A., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M. J., Heyd J. J., Brothers E. N., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Keith T. A., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A. P., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Millam J. M., Klene M., Adamo C., Cammi R., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Farkas O., Foresman J. B., and Fox D. J., Gaussian09, revision E.01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Li H. Feng Y. P. Shen L. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:2611–2617. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeber A. E. Mazziotti D. A. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020;22:23998–24003. doi: 10.1039/D0CP04172F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedik N. Kulichenko M. Steglenko D. Boldyrev A. I. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:2711–2714. doi: 10.1039/C9CC09483K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Lu T. Chen Q. Carbon. 2020;165:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2020.04.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arulmozhiraja S. Ohno T. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:114301. doi: 10.1063/1.2838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. M. L. El-Yazal J. François J.-P. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995;242:570–579. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(95)00801-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Momma K. Izumi F. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011;44:1272–1276. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811038970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:1007–1023. doi: 10.1063/1.456153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ANIS M. S., Abby-Mitchell, Abraham H., AduOffei, Agarwal R., Agliardi G., Aharoni M., Akhalwaya I. Y., Aleksandrowicz G., Alexander T., Amy M., Anagolum S., Anthony-Gandon, Arbel E., Asfaw A., Athalye A., Avkhadiev A., Azaustre C., BHOLE P., Banerjee A., Banerjee S., Bang W., Bansal A., Barkoutsos P., Barnawal A., Barron G., Barron G. S., Bello L., Ben-Haim Y., Bennett M. C., Bevenius D., Bhatnagar D., Bhobe A., Bianchini P., Bishop L. S., Blank C., Bolos S., Bopardikar S., Bosch S., Brandhofer S., Brandon, Bravyi S., Bronn N., Bryce-Fuller, Bucher D., Burov A., Cabrera F., Calpin P., Capelluto L., Carballo J., Carrascal G., Carriker A., Carvalho I., Chen A., Chen C.-F., Chen E., Chen J. C., Chen R., Chevallier F., Chinda K., Cholarajan R., Chow J. M., Churchill S., CisterMoke, Claus C., Clauss C., Clothier C., Cocking R., Cocuzzo R., Connor J., Correa F., Crockett Z., Cross A. J., Cross A. W., Cross S., Cruz-Benito J., Culver C., Córcoles-Gonzales A. D., N. D., Dague S., Dandachi T. E., Dangwal A. N., Daniel J., Daniels M., Dartiailh M., Davila A. R., Debouni F., Dekusar A., Deshmukh A., Deshpande M., Ding D., Doi J., Dow E. M., Drechsler E., Dumitrescu E., Dumon K., Duran I., EL-Safty K., Eastman E., Eberle G., Ebrahimi A., Eendebak P., Egger D., ElePT, Emilio, Espiricueta A., Everitt M., Facoetti D., Farida, Fernández P. M., Ferracin S., Ferrari D., Ferrera A. H., Fouilland R., Frisch A., Fuhrer A., Fuller B., GEORGE M., Gacon J., Gago B. G., Gambella C., Gambetta J. M., Gammanpila A., Garcia L., Garg T., Garion S., Garrison J. R., Garrison J., Gates T., Gil L., Gilliam A., Giridharan A., Gomez-Mosquera J., Gonzalo, de la Puente González S., Gorzinski J., Gould I., Greenberg D., Grinko D., Guan W., Guijo D., Gunnels J. A., Gupta H., Gupta N., Günther J. M., Haglund M., Haide I., Hamamura I., Hamido O. C., Harkins F., Hartman K., Hasan A., Havlicek V., Hellmers J., Herok Ł., Hillmich S., Horii H., Howington C., Hu S., Hu W., Huang J., Huisman R., Imai H., Imamichi T., Ishizaki K., Ishwor, Iten R., Itoko T., Ivrii A., Javadi A., Javadi-Abhari A., Javed W., Jianhua Q., Jivrajani M., Johns K., Johnstun S., Jonathan-Shoemaker, JosDenmark, JoshDumo, Judge J., Kachmann T., Kale A., Kanazawa N., Kane J., Kang-Bae, Kapila A., Karazeev A., Kassebaum P., Kehrer T., Kelso J., Kelso S., Khanderao V., King S., Kobayashi Y., Kovi11Day, Kovyrshin A., Krishnakumar R., Krishnan V., Krsulich K., Kumkar P., Kus G., LaRose R., Lacal E., Lambert R., Landa H., Lapeyre J., Latone J., Lawrence S., Lee C., Li G., Lishman J., Liu D., Liu P., Lolcroc, A. K. M., Madden L., Maeng Y., Maheshkar S., Majmudar K., Malyshev A., Mandouh M. E., Manela J., Manjula, Marecek J., Marques M., Marwaha K., Maslov D., Maszota P., Mathews D., Matsuo A., Mazhandu F., McClure D., McElaney M., McGarry C., McKay D., McPherson D., Meesala S., Meirom D., Mendell C., Metcalfe T., Mevissen M., Meyer A., Mezzacapo A., Midha R., Miller D., Minev Z., Mitchell A., Moll N., Montanez A., Monteiro G., Mooring M. D., Morales R., Moran N., Morcuende D., Mostafa S., Motta M., Moyard R., Murali P., Müggenburg J., NEMOZ T., Nadlinger D., Nakanishi K., Nannicini G., Nation P., Navarro E., Naveh Y., Neagle S. W., Neuweiler P., Ngoueya A., Nguyen T., Nicander J., Nick-Singstock, Niroula P., Norlen H., NuoWenLei, O'Riordan L. J., Ogunbayo O., Ollitrault P., Onodera T., Otaolea R., Oud S., Padilha D., Paik H., Pal S., Pang Y., Panigrahi A., Pascuzzi V. R., Perriello S., Peterson E., Phan A., Pilch K., Piro F., Pistoia M., Piveteau C., Plewa J., Pocreau P., Pozas-Kerstjens A., Pracht R., Prokop M., Prutyanov V., Puri S., Puzzuoli D., Pérez J., Quant02, Quintiii, Rahman R. I., Raja A., Rajeev R., Rajput I., Ramagiri N., Rao A., Raymond R., Reardon-Smith O., Redondo R. M.-C., Reuter M., Rice J., Riedemann M., Rietesh, Risinger D., Rocca M. L., Rodríguez D. M., RohithKarur, Rosand B., Rossmannek M., Ryu M., SAPV T., Sa N. R. C., Saha A., Ash-Saki A., Sanand S., Sandberg M., Sandesara H., Sapra R., Sargsyan H., Sarkar A., Sathaye N., Schmitt B., Schnabel C., Schoenfeld Z., Scholten T. L., Schoute E., Schulterbrandt M., Schwarm J., Seaward J., Sergi, Sertage I. F., Setia K., Shah F., Shammah N., Sharma R., Shi Y., Shoemaker J., Silva A., Simonetto A., Singh D., Singh D., Singh P., Singkanipa P., Siraichi Y., Siri, Sistos J., Sitdikov I., Sivarajah S., Sletfjerding M. B., Smolin J. A., Soeken M., Sokolov I. O., Sokolov I., Soloviev V. P., SooluThomas, Starfish, Steenken D., Stypulkoski M., Suau A., Sun S., Sung K. J., Suwama M., Słowik O., Takahashi H., Takawale T., Tavernelli I., Taylor C., Taylour P., Thomas S., Tian K., Tillet M., Tod M., Tomasik M., Tornow C., de la Torre E., Toural J. L. S., Trabing K., Treinish M., Trenev D., TrishaPe, Truger F., Tsilimigkounakis G., Tulsi D., Turner W., Vaknin Y., Valcarce C. R., Varchon F., Vartak A., Vazquez A. C., Vijaywargiya P., Villar V., Vishnu B., Vogt-Lee D., Vuillot C., Weaver J., Weidenfeller J., Wieczorek R., Wildstrom J. A., Wilson J., Winston E., WinterSoldier, Woehr J. J., Woerner S., Woo R., Wood C. J., Wood R., Wood S., Wootton J., Wright M., Xing L., YU J., Yang B., Yang U., Yao J., Yeralin D., Yonekura R., Yonge-Mallo D., Yoshida R., Young R., Yu J., Yu L., Zachow C., Zdanski L., Zhang H., Zidaru I., Zoufal C., aeddins ibm, alexzhang13, b63, bartek bartlomiej, bcamorrison, brandhsn, charmerDark, deeplokhande, dekel.meirom, dime10, dlasecki, ehchen, fanizzamarco, fs1132429, gadial, galeinston, georgezhou20, georgios ts, gruu, hhorii, hykavitha, itoko, jeppevinkel, jessica angel7, jezerjojo14, jliu45, jscott2, klinvill, krutik2966, ma5x, michelle4654, msuwama, nico lgrs, ntgiwsvp, ordmoj, sagar pahwa, pritamsinha2304, ryancocuzzo, saktar unr, saswati qiskit, septembrr, sethmerkel, sg495, shaashwat, smturro2, sternparky, strickroman, tigerjack, tsura crisaldo, upsideon, vadebayo49, welien, willhbang, wmurphy collabstar, yang.luh and Cepulkovskis M., Qiskit: An Open-source Framework for Quantum Computing, 2021

- LaRose R., Mari A., Kaiser S., Karalekas P. J., Alves A. A., Czarnik P., Mandouh M. E., Gordon M. H., Hindy Y., Robertson A., Thakre P., Shammah N. and Zeng W. J., 2021, arXiv:2009.04417

- Welborn M. Tsuchimochi T. Van Voorhis T. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;145:074102. doi: 10.1063/1.4960986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H.-Z. Ricke N. D. Tran H. K. Van Voorhis T. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:4497–4506. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H.-Z. Tran H. K. Van Voorhis T. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:5035–5046. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle S. Jones T. Endo S. Li Y. Benjamin S. C. Yuan X. npj Quantum Inf. 2019;5:75. doi: 10.1038/s41534-019-0187-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X. Endo S. Zhao Q. Li Y. Benjamin S. C. Quantum. 2019;3:191. doi: 10.22331/q-2019-10-07-191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi H. Kosugi T. Matsushita Y.-i. npj Quantum Inf. 2021;7:85. doi: 10.1038/s41534-021-00409-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M. Sun C. Tan A. T. O'Rourke M. J. Ye E. Minnich A. J. Brandão F. G. Chan G. K.-L. Nat. Phys. 2020;16:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Huo M. and Li Y., Shallow Trotter circuits fulfil error-resilient quantum simulation of imaginary time 2021, arXiv:2109.07807

- Zeng P., Sun J. and Yuan X., 2021

- Temme K. Bravyi S. Gambetta J. M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:180509. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.180509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S. Benjamin S. C. Li Y. Phys. Rev. X. 2018;8:031027. [Google Scholar]

- Strikis A. Qin D. Chen Y. Benjamin S. C. Li Y. PRX Quantum. 2021;2:040330. doi: 10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.040330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. Yuan X. Tsunoda T. Vedral V. Benjamin S. C. Endo S. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021;15:034026. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.034026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bravyi S. Sheldon S. Kandala A. Mckay D. C. Gambetta J. M. Phys. Rev. A. 2021;103:042605. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.103.042605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Wood C. J., Yoder T. J., Merkel S. T., Gambetta J. M., Temme K. and Kandala A., 2021, arXiv:2108.09197

- Huang H.-Y. Kueng R. Preskill J. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;127:030503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.030503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Sun J., Huang Q. and Yuan X., 2021, arXiv:2105.13091

- Zhang T. Sun J. Fang X.-X. Zhang X. Yuan X. Lu H. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;127:200501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. M. Mazziotti D. A. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2018;122:4988–4996. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Guo S. Sun Q. Chan G. K.-L. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:1026–1033. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this paper are available at Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6544996.