Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is the most common form of spinal cord impairment in adults. DCM is an important, disabling and unfortunately frequently overlooked condition, which is estimated to affect as many as one in 50 adults.1–4 Despite the prevalence of DCM, awareness of this condition among members of the public and even among physicians is lacking. Thus, many patients do not receive a timely diagnosis, with wait times to the time of diagnosis ranging on average two to five years. Given the frequent delays in diagnosis and treatment, many will be left with lifelong disabilities despite appropriate surgical intervention.5 AO Spine RECODE DCM (REsearch Objectives and Common Data Elements for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy) (https://www.aospine.org/recode) was formed as an international, interdisciplinary, and interprofessional initiative, including patients with DCM. One of the research priorities is the development of comprehensive diagnostic criteria for DCM6,7 to facilitate early diagnosis and timely management.8 This requires standardized clinical evaluation metrics based on objective and reproducible signs and symptoms coupled with advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) approaches with standardized evaluation approaches. This is pertinent to DCM, as MRI findings, such as cord compression, are often incidental and only weakly correlate with disease severity. To stimulate research and awareness, we discuss a proposed diagnostic framework to advance the role of imaging in the diagnosis of DCM.9

THE ROLE OF NEUROIMAGING FOR DIAGNOSIS OF NEUROLOGICAL DISEASES

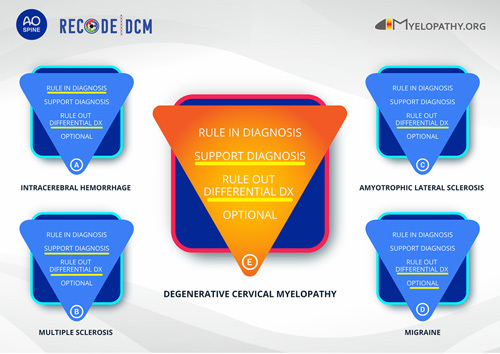

In neurological conditions, the additional value of imaging for diagnosing a specific disorder ranges between “rule in” a diagnosis and being “optional” (Figure 1). In most conditions, imaging is additionally used to exclude differential diagnoses. For instance, for the diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage, a computed tomography scan can “rule in” the diagnosis (Figure 1A).10 In other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, when clinical signs and/or symptoms are present, additional imaging is needed to “support” the final diagnosis (Figure 1B).11 Then, in some conditions, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, imaging is needed to “rule out” differential diagnoses, while the diagnosis relies on clinical findings (Figure 1C).12 Last, imaging can be considered “optional,” for example, in migraine (Figure 1D).13 This framework represents a simplification not covering cases with aberrant findings or all advantages that highly specialized imaging provides. However, this framework reflects the implicit system routinely used by neurologists and neurosurgeons. Therefore, it is logical to conclude that DCM criteria following this framework would permit high levels of acceptance and utility.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic framework to understand the role of neuroimaging in neurological diseases and application to degenerative cervical myelopathy.

APPLICATION OF NEUROIMAGING FRAMEWORK IN DCM

In DCM, cervical spine imaging, and in particular MRI, is essential for the diagnosis and is not optional, as spinal canal narrowing is a prerequisite for spinal cord compression. However, given the high prevalence of patients with asymptomatic spinal canal stenosis,14 the strong interrelation of degenerative features,15 and the challenges of correlating clinical and radiological findings,16 we advocate that spinal canal narrowing alone does not suffice to make the diagnosis of DCM. An accurate diagnostic approach will thus need to define the other characteristics, such as signs and symptoms, that permit a final diagnosis when cervical canal narrowing is present on MRI. In addition, differential diagnoses, for example, multiple sclerosis and tumor, should be ruled out with MRI (Figure 1E).

ADVANCED NEUROIMAGING: FROM SPINAL STENOSIS TO MEASURES OF SPINAL CORD DISTRESS

To enhance the utility of cervical spine MRI, several advanced neuroimaging methods are in various stages of translation.17 Their entry into clinical practice may adjust the role of MRI in the diagnosis of DCM, for example, to rule in a diagnosis of DCM. These include phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PCMR) to measure craniocaudal motion of the spinal cord and cerebrospinal fluid, microstructural and functional imaging of the spinal cord, and spinal cord perfusion imaging.18,19 PCMR in DCM has repeatedly demonstrated that spinal cord motion was increased at the level of stenosis and adjacent to the level of stenosis.20–23 This approach also demonstrated cerebrospinal fluid flow was increased at the level of stenosis.24 Interestingly, the authors have demonstrated a correlation between deranged cerebrospinal fluid flow and radiological evidence for myelopathy, and normalization of flow following decompressive surgery. Therefore, PCMR holds the potential to detect correlates of effective decompression. Microstructural imaging provides the unique opportunity to quantify spinal cord tissue properties. Diffusion tensor imaging allows for the assessment of axonal and myelin integrity. Among the best studied diffusion tensor imaging metrics, apparent diffusion coefficient, a rate of water motion without reference to the direction, and fractional anisotropy, a measure for water to diffuse in one direction, are best investigated in DCM. It was consistently demonstrated that an increased apparent diffusion coefficient and reduced fractional anisotropy had higher sensitivity and specificity to identify patients with DCM than T2-weighted hyperintensity.25,26 Moreover, quantitative MRI allowed for detection of subclinical tissue injury in patients with asymptomatic spinal canal stenosis before the onset of symptoms,27 and it was shown to be sensitive for myelopathic progression.28 In addition, it has been demonstrated that tract-specific neurodegeneration can be found remote to the level of compression,29–31 indicating that the mechanisms behind the clinical evolution of DCM are not restricted to focal cervical cord pathology, but involve complex degeneration across the spinal axis. Functional MRI and perfusion imaging are still nascent in the field of DCM but hold potential to increase our understanding of impaired spinal neuronal networks in DCM,32 respectively, to elucidate the role of chronic hypoperfusion for the clinical evolution of DCM.33

SPINAL CORD DISTRESS AND TIMELY MANAGEMENT

The translation of these techniques is most likely to benefit patients with mild forms of DCM where there is greater diagnostic uncertainty, for example, with fewer displaying the more objective examination findings (e.g., Hoffman sign), but also given the management uncertainty; are the risks of surgery warranted against the natural history of mild DCM? In keeping with DCM research in general,34 relatively few imaging studies have investigated mild myelopathy. Martin et al 27 used microstructural MRI, in particular T2* gray matter/white matter ratio assessment, to identify subclinical evidence of spinal cord damage in a cohort of patients with cervical stenosis, thus confirming promise. This finding is supported by similar studies using multimodal evoked potentials, suggesting solutions may also lie outside of imaging.35,36 Whatever the modality, the development of assessments to unlock this conundrum is crucial: being able to identify who requires surgery, and perform it before there is irreversible damage, would transform outcomes for DCM, moving it from a paradigm of reactive to pre-emptive care.5

IMMEDIATE OUTLOOK

While these new modalities remain in development, there are many simpler gains. For example, from discussions within the RECODE DCM working group, it became apparent the imaging framework would support educational initiatives. For example, those living with DCM referenced the common “lay” misconception that a diagnostic test provides certainty. For similar reasons, this could help raise awareness among nonexpert professionals, to identify those with seemingly mild stenosis and symptoms and allow for timely management, while avoiding surgery in patients with asymptomatic stenosis.

Future directions in the neuroimaging evaluation of DCM require a standardized definition of spinal canal narrowing, spinal cord compression and intrinsic cord signal changes. Systematic literature reviews with consensus-based evidence synthesis could set the stage for the development of an objective imaging diagnostic framework for DCM. Creating a simple framework for diagnosis in DCM has the potential to dramatically change care and outcomes.5,7 Novel methods for determining spinal cord distress are currently under examination and may reshape our view on DCM, but remain a work in progress. We look forward to the feedback and perspectives of the community and hope more will work with us on this endeavor.

Acknowledgments

M.G.F. acknowledge support from the Robert Campeau Family Foundation/Dr. C.H. Tator Chair in Brain and Spinal Cord Research at UHN.

Footnotes

Supported by AO Spine through the AO Spine Knowledge Forum Spinal Cord Injury, a focused group of international Spinal Cord Injury experts, as part of the AO Spine RECODE DCM project. AO Spine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation, which is an independent medically guided not-for-profit organisation.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Carl M. Zipser, Email: CarlMoritz.Zipser@balgrist.ch.

Michael G. Fehlings, Email: michael.fehlings@uhn.on.ca;tworden81@gmail.com;michael.fehlings@uhn.ca.

Konstantinos Margetis, Email: konstantinos.margetis@mountsinai.org.

Armin Curt, Email: Armin.Curt@balgrist.ch.

Michael Betz, Email: Michael.Betz@balgrist.ch.

Iwan Sadler, Email: iwan@myelopathy.org.

Lindsay Tetreault, Email: lindsay.tetreault89@gmail.com.

Benjamin M. Davies, Email: bd375@cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Hejrati N, Moghaddamjou A, Marathe N, Fehlings MG. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: towards a personalized approach. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipser CM, Margetis K, Pedro KM, et al. Increasing awareness of degenerative cervical myelopathy: a preventative cause of non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021;59:1216–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badhiwala JH, Ahuja CS, Akbar MA, et al. Degenerative cervical myelopathy—update and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:108–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Spine. 2015;40:E675–E693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies BM, Mowforth O, Wood H, et al. Improving awareness could transform outcomes in degenerative cervical myelopathy [AO Spine RECODE-DCM Research Priority Number 1]. Glob Spine J. 2022;12(1 suppl):28S–38S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies BM, Kwon BK, Fehlings MG, Kotter MRN. AO Spine RECODE-DCM: why prioritize research in degenerative cervical myelopathy? Glob Spine J. 2022;12(1 suppl):5S–7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilton B, Gardner EL, Jiang Z, et al. Establishing diagnostic criteria for degenerative cervical myelopathy [AO Spine RECODE-DCM Research Priority Number 3]. Glob Spine J. 2022;12(1 suppl):55s–63s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies BM, Khan DZ, Mowforth OD, et al. RE-CODE DCM (REsearch Objectives and Common Data Elements for Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy): a consensus process to improve research efficiency in DCM, through establishment of a standardized dataset for clinical research and the definition of the research priorities. Glob Spine J. 2019;9(1 suppl):65S–76S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerner A. Diagnostic Criteria in Neurology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health Cluster. WHO STEPS Stroke Manual: the WHO STEPwise Approach to Stroke Surveillance/Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health, World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SS, Stewart ME, Davies BM, Kotter MRN. The prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic spinal cord compression on magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Spine J. 2021;11:597–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nouri A, Martin AR, Tetreault L, et al. MRI analysis of the combined prospectively collected AOSpine North America and International Data: the prevalence and spectrum of pathologies in a global cohort of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy. Spine. 2017;42:1058–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouri A, Tetreault L, Dalzell K, Zamorano JJ, Fehlings MG. The relationship between preoperative clinical presentation and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging features in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David G, Mohammadi S, Martin AR, et al. Traumatic and nontraumatic spinal cord injury: pathological insights from neuroimaging. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:718–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin AR, Tetreault L, Nouri A, et al. Imaging and electrophysiology for degenerative cervical myelopathy [AO Spine RECODE-DCM Research Priority Number 9]. Glob Spine J. 2022;12(1 suppl):130S–146S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin AR, Aleksanderek I, Cohen-Adad J, et al. Translating state-of-the-art spinal cord MRI techniques to clinical use: a systematic review of clinical studies utilizing DTI, MT, MWF, MRS, and fMRI. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;10:192–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hupp M, Pfender N, Vallotton K, et al. The restless spinal cord in degenerative cervical myelopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021;42:597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf K, Hupp M, Friedl S, et al. In cervical spondylotic myelopathy spinal cord motion is focally increased at the level of stenosis: a controlled cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vavasour IM, Meyers SM, MacMillan EL, et al. Increased spinal cord movements in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine J. 2014;14:2344–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka H, Sakurai K, Iwasaki M, et al. Craniocaudal motion velocity in the cervical spinal cord in degenerative disease as shown by MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang HS, Nejo T, Yoshida S, Oya S, Matsui T. Increased flow signal in compressed segments of the spinal cord in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2014;39:2136–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demir A, Ries M, Moonen CT, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient and apparent diffusion tensor maps in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Radiology. 2003;229:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mamata H, Jolesz FA, Maier SE. Apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy in spinal cord: age and cervical spondylosis-related changes. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin AR, De Leener B, Cohen-Adad J, et al. Can microstructural MRI detect subclinical tissue injury in subjects with asymptomatic cervical spinal cord compression? A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin AR, De Leener B, Cohen-Adad J, et al. Monitoring for myelopathic progression with multiparametric quantitative MRI. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seif M, David G, Huber E, Vallotton K, Curt A, Freund P. Cervical cord neurodegeneration in traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vallotton K, David G, Hupp M, et al. Tracking White and gray matter degeneration along the spinal cord axis in degenerative cervical myelopathy. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:2978–2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabher P, Mohammadi S, David G, Freund P. Neurodegeneration in the spinal ventral horn prior to motor impairment in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2329–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Qian W, Jin R, et al. Amplitude of low frequency fluctuation (ALFF) in the cervical spinal cord with stenosis: a resting state fMRI study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0167279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellingson BM, Woodworth DC, Leu K, Salamon N, Holly LT. Spinal cord perfusion MR imaging implicates both ischemia and hypoxia in the pathogenesis of cervical spondylosis. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:e773–e781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grodzinski B, Bestwick H, Bhatti F, et al. Research activity amongst DCM research priorities. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2021;163:1561–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheuren PS, David G, Kipling Kramer JL, et al. Combined neurophysiologic and neuroimaging approach to reveal the structure-function paradox in cervical myelopathy. Neurology. 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jutzeler CR, Ulrich A, Huber B, Rosner J, Kramer JLK, Curt A. Improved diagnosis of cervical spondylotic myelopathy with contact heat evoked potentials. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2045–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]