Abstract

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) is a 12-item measure of functional social support (SS); however, the psychometric properties of the MSPSS have not been evaluated in prisoners. We used measures of known-groups validity, convergent and discriminant validity, internal consistency reliability and factor structure to assess the suitability of the MSPSS for measuring SS among 184 individuals in prison in the U.S., who were diagnosed with depression. The MSPSS was correlated with scores on scales measuring related constructs (i.e., loneliness), and uncorrelated with unrelated constructs (i.e., verbal ability). Correlations among items of the MSPSS on the same subscale were large, and small to moderate among items of different subscales. The overall Cronbachʼs α for the scale was 0.93. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the theorized three-factor solution for the MSPSS (i.e., significant other, family, and friends) provided a good fit for the data. We recommend using the MSPSS to measure perceived SS among incarcerated individuals.

Keywords: confirmatory factor analysis, incarceration, major depressive disorder, multidimensional scale of perceived social support, psychometrics, social support

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In the U.S., more than two million people are held in state and federal prisons and jails on any given day (Kaeble, Glaze, Tsoutis, & Minton, 2015). Events before incarceration or even incarceration itself can lead to breakdown in individualʼs social support networks or to their perceived lack of access to social support. Global (Fazel & Danesh, 2002) and U.S.(James & Glaze, 2006) data indicate that people in prison suffer from mental disorders, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) at rates much higher than the general population. Estimates of current MDD among people in U.S. prisons ranges upwards to 29% (Prins, 2014). Social support theory indicates that low social support is a significant risk factor for MDD in incarcerated populations; likewise, high social support can buffer mental health complaints (Johnson et al., 2011; Lakey & Cronin, 2008; Marzano, Hawton, Rivlin, & Fazel, 2011; McCarty, Vander Stoep, Kuo, & McCauley, 2006; Potts, 1997). Literature on the mechanism by which social support effects mental health suggests that social support protects people from MDD by buffering the effects of stress on mood (Johnson et al., 2011). Interventions for mental disorders, such as interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), that are currently being evaluated in prison settings (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012; Johnson et al., 2019), seek to improve mental health status by strengthening interpersonal relationships and the social functioning of those affected (Wilfley, 2000). Indeed, there is evidence that the general supportiveness of incarcerated individuals’ social support networks is modifiable (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008; Nargiso, Kuo, Zlotnick, & Johnson, 2014).

Social support is also beneficial to incarcerated adults’ health and well-being in other ways. Higher social support is strongly associated with lower suicidality in prison, more treatment engagement during prison, better understanding of prison program rules, and more prison program participation (Joe et al., 2012; Marzano et al., 2011; Rivlin, Hawton, Marzano, & Fazel, 2013; Sacks & Kressel, 2005; Way, Miraglia, Sawyer, Beer, & Eddy, 2005). Maintaining strong supports during incarceration is also important for preventing recidivism (Bales & Mears, 2008; Cochran, 2014), and promoting positive employment outcomes at re-entry (Berg & Huebner, 2011; Feaster et al., 2013; Naser & La Vigne, 2006). There is a need to provide clinicians in correctional settings with an accurate assessment of incarcerated adults’ social support to guide their efforts to treat common mental health problems like MDD, reduce suicidality, prepare for re-entry, and improve other outcomes. Given that social support plays a central role in the etiology and treatment of MDD (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012; McCarty et al., 2006), being able to accurately assess social support among people in prison with MDD is especially important for guiding clinical care. To do this, a psychometrically sound measure of social support among incarcerated adults is required, yet there are no known measures of social support for prison populations.

2 |. SOCIAL SUPPORT

Social support is commonly defined as the perceived or actual expressive or instrumental support provided by informal relations or formal agencies (Cullen, 1994; Lin, 1986). Social support encompasses both structural (i.e., the number and size of available social support networks) and functional (i.e., the perception that one has access to, and the quality of, social support) components. As a protective factor, social support is hypothesized to impact health through direct and indirect pathways (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Uchino, 2006). Structural aspects of social support protect against ill health through direct means, such as encouraging healthy behaviors like physical activity, good nutrition, and adherence to medications (DiMatteo, 2004; Uchino, 2006). On the other hand, functional or perceived social support is believed to buffer the effects of an established stressor on oneʼs wellbeing (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Norris & Murrell, 1990).Psychotherapies, such as IPT, directly target social support to decrease related symptoms (i.e., depressive symptoms and interpersonal problems; Lipsitz & Markowitz, 2013; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012).

Social support is an important construct across populations and contexts including in the criminal justice system (Vaingankar, Abdin, & Chong, 2012; Zhou et al., 2015). Prior research suggests higher social support is associated with lower symptoms of depression, lower rule breaking behaviors, and lower rates of recidivism following release (Cochran, 2014; De Claire & Dixon, 2017). Unfortunately, social supports that existed before incarceration are often reduced or severed. Access to social supports outside of prison is often limited in frequency, duration, and form of contact (e.g., visitation, mail, phone calls, and special programs). Prison guests who participate in visitation often have to take time off work, arrange childcare, and travel long distances to visit, especially if the prisoner is a woman (Christian, 2005). Prison facilities can also be intimidating or in poor condition (e.g., limited space) to accept visitors (Cochran, 2014). In terms of phone calls, people in prison often cannot afford the cost. Therefore, needs for social support often fall to others in prison. However, opportunities for social support within prison are also limited. People frequently enter prison not knowing others and prisons are inherently challenging settings to develop new close relationships (e.g., transiency, risk of victimization, environmental barriers; Schaefer, Bouchard, Young, & Kreager, 2017). Prior research on social support in prison settings found that men and women both have an interest in close relationships and believe they are valuable (Schaefer et al., 2017). Specifically, men and women report close relationships in prison provide companionship, help deter problem behaviors, and promote self-improvement.

3 |. THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCALE OF PERCEIVED SOCIAL SUPPORT

Given the important role of social support among incarcerated adults, it is important to have a psychometrically sound measure of social support. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS; Appendix A) is a frequently used 12-item instrument developed by Zimet et al. to assess the subjective adequacy of an individuals’ social support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). Since the MSPSS was first published in 1988, it has been used extensively in both healthy and clinical samples to assess respondents’ perceived social support (Bruwer, Emsley, Kidd, Lochner, & Seedat, 2008; Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000;Dahlem, Zimet, & Walker, 1991; Eker, Arkar, & Yaldız, 2001; Kazarian & McCabe, 1991; Stanley, Beck, & Zebb, 1998; Vaingankar et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2015; Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, & Berkoff, 1990). The MSPSS is preferred for use in many contexts because it is brief, and provides measures of support from significant others (SO), family (FAM), and friends (FRI). Studies in non-incarcerated populations suggest that the MSPSS has good convergent and discriminant validity and internal consistency reliability in many populations (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Ekbäck, Benzein, Lindberg, & Årestedt, 2013; Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet et al., 1990). There is also empirical support for the original three-factor structure of the MSPSS (i.e., one factor for SO, FAM, and FRI) in most populations, including university students (Dahlem et al., 1991; Zimet et al., 1988), urban African American adolescents (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000), South African youth (Bruwer et al., 2008), and patients affected by psychiatric disorders (Cecil, Stanley, Carrion, & Swann, 1995; Vaingankar et al., 2012). In most settings moderate to large inter-factor correlations have been reported for the MSPSS with correlations as high as 0.56 between the SO and FAM subscales, 0.87 between the SO and FRI subscale, and 0.83 between the FAM and FRIs subscales (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Ekbäck et al., 2013).

Two examples of the MSPSS not fully supporting a three-factor solution, however, include a study by Zhou and colleagues involving Chinese mainland patients (n = 1,212) participating in methadone maintenance treatment (Zhou et al., 2015) and a study by Stanley et al. (1998) involving older adults with generalized anxiety disorder (n = 50) and normal controls (n = 94). Whereas findings from both studies showed that the MSPSS had strong measures of internal consistency reliability, factor analytic findings did not result in the original three-factor structure. Zhou et al. (2015) found a two-factor structure, one factor for FAM and one factor for SO and FRI, and hypothesized that patients may have viewed FAM as a key source of support and may not have perceived a distinction among support from SOs and FRIs. Stanley et al. (1998) also found a two-factor structure for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder though one factor consisted of SOs and FAM members and the second was comprised of items from the FRI subscale. Thus, the MSPSS generally, but not always, performs as expected, so it is important to ensure the scale is suitable before adopting it for use in new populations.

4 |. THE PRESENT STUDY

The MSPSS has been used in studies of incarcerated adults’ functional social support (Brown & Day, 2008; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008; Nargiso et al., 2014; Zhang, Grabiner, Zhou, & Li, 2010) without evaluation of its psychometric properties. For the MSPSS to be adopted to measure perceived social support among incarcerated adults with MDD, or incarcerated adults in general, its psychometric properties among incarcerated adults should be evaluated. It is possible that the MSPSS could not perform as well in a prison setting as it has among non-prison samples given restrictions on incarcerated adults regarding when, how, and how long they can access social supports, such as SOs and FAM members. Given the high prevalence and adverse effects of MDD among prison populations, and the use of the MSPSS in previous and ongoing studies of incarcerated adults with MDD, this study assesses construct validity (i.e., known-groups, convergent, and divergent validity), internal consistency and composite reliability, and factor structure of the MSPSS as a metric for perceived social support among incarcerated adults with MDD. There is no known study of the psychometric properties of the MSPSS among incarcerated adults with MDD or incarcerated adults in general. We hypothesized that the three- factor structure of the MSPSS would be replicated among incarcerated adults with depression and that the scale would have adequate validity and reliability in the present sample. Results from this study will indicate whether the MSPSS can be used by clinicians, public health professionals, and other scholars to measure perceived social support among people in prison suffering from MDD in particular as well as provide information relevant to its use among incarcerated adults in general.

5 |. METHODS

5.1 |. Design

This is a cross-sectional study using pretreatment (baseline) data collected among incarcerated adults recruited as part of a study designed to test the effectiveness of IPT for incarcerated men and women with MDD in the U.S. The parent study (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012) used the MSPSS and is the first fully-powered randomized controlled trial (RCT) of any treatment (psychological or psychopharmacological) for MDD in any incarcerated population. The data being reported for this study were collected from participants at enrollment which occurred before randomization into the two arms of the RCT (Johnson et al., 2016).

5.2 |. Procedures and sampling

Participants were recruited from womenʼs prison facilities and menʼs medium security prison facilities in Rhode Island (RI) and Massachusetts (MA) over a period of three years: from March 5, 2011 to March 21, 2014. At the time of the RCT, the recruitment sites housed the entire womenʼs prison population for MA and RI, the entire medium security prison population for men in RI, and part of the medium security prison population in MA. Eligible participants for this study were required to: (a) be sentenced men and women aged between 18 and 65 years held in any one of the participating institutions; (b) meet the DSM-IV criteria for current, non-substance induced, MDD after at least 4 weeks of incarceration as determined by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV disorders (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002); and (c) self-reported being likely to stay at their current facilities for at least six months given expected release dates or pending transfers to other facilities. Individuals were excluded if they met lifetime criteria for bipolar disorder or primary psychotic disorder (individuals with psychotic MDD were included).

Written informed consent was obtained from participants before they were enrolled into the study (for detailed procedures, see Johnson et al., 2016). The primary study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brown University (#1105000382) and of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (#268370-14) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01685294). Study assessments were conducted by study research assistants who were blinded to treatment condition. Study assessments took place in private rooms with no prison staff present. Data were kept strictly confidential from prison staff, and confidentiality of data was protected by a federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

Incarcerated individuals (n = 599) submitted interest slips to find out more about the study. Of these, 237 were ineligible at initial screening. The primary reasons for ineligibility at screening were that prospective participants did not expect to remain at their facilities for six or more months (n = 126), and being no longer interested/too busy (n = 64). Of the 362 potential participants assessed for full eligibility following screening, 184 were eligible and were included in this analysis. Individuals who were excluded included 6 who declined consent, 23 who consented but changed their minds before randomization, and others who were ineligible for other reasons (e.g., did not meet criteria for MDE). A full CONSORT diagram can be found in Johnson et al. (2019).

5.3 |. Measures

Trained research assistants (RAs) administered structured questionnaire and self-report measures, including the SCID, to consenting adult men and women who met the inclusion criteria for this study. Assessments included severity of their current major depressive episode (MDE) using the 17-item revised Hamilton rating scales for depression (HAM-D), UCLA loneliness scale (UCLA LS), expressive vocabulary test-second edition (EVT-2), MSPSS, and demographic information. The study principal investigator and a clinical interviewing trainer supervised the RAs. Reliability checks were made periodically throughout the study and ongoing training provided. Interrater reliability was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.97 across raters for the HAM-D).

5.3.1 |. Hamilton rating scales for depression

All study participants met criteria for a current MDE per the SCID-IV. However, individual incarcerated adults included in the study were at varying levels of severity of their current MDE. Therefore, we used the interviewer-rated, 17-item revised HAM-D (Hamilton, 1980) to assess incarcerated adults’ depressive symptoms, calculated the HAM-D score for each prisoner and used the resultant score as a metric of the severity of incarcerated adults current MDE. Scores were calculated based on severity of symptoms on items, such as depressed mood, somatic symptoms, insomnia, and weight. Possible scores range from 0 to 46, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Scores of 0–7 indicate no depression, scores of 8–16 indicate mild depression, scores of 17–23 indicate moderate depression, and scores of 24 and above indicate severe depression (Zimmerman, Martinez, Young, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, 2013). Half (50%) of participants in this study scored 24 or above, indicating severe depression, and were coded as having a severe current MDE. Those with scores less than 24 were coded as having non-severe current MDE. The HAM-D is a well-validated and reliable 17-item measure used extensively in MDD treatment studies (Keller, 2003) and in our prison pilot studies (Johnson, Williams, & Zlotnick, 2015; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008). In the current study, HAM-D internal consistency was satisfactory (Cronbachʼs α = 0.74) and interrater reliability was excellent, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.97 across raters.

5.3.2 |. UCLA loneliness scale

The revised UCLA LS (Russell, 1996) was used to measure incarcerated adults’ loneliness (i.e., satisfaction and dissatisfaction with their social relationships). The original UCLA LS is a 20 item self-report questionnaire; however, Russell (1996) also suggests a briefer, 10-item version of the scale that is reliable (Cronbachʼs α of 0.89 and item-total correlations ranging between 0.56 and 0.73) and amenable for use among time constrained respondents. This study used the 10-item version, which had a Cronbachʼs α of 0.85 in the current study. Items on the 10-item UCLA LS refer to, for example, “How often do you feel unhappy doing so many things alone?” or “How often do you feel completely alone?” Respondents chose among four response options: “I often feel this way” (Scored 4), “I sometimes feel this way” (Scored 3), “I rarely feel this way” (Scored 2) or “I never feel this way” (Scored 1). Possible scores ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness.

5.3.3 |. Expressive vocabulary test, second edition

The EVT-2 screener items were administered to provide additional data regarding each study participantʼs verbal communication skills including word acquisition and/or retrieval. The EVT-2 consists of a total of 190 items (including the five screener items) featuring a series of pictures depicting objects, people, and situations. During the administration of the EVT-2, respondents were given a stimulus question and prompted to name or describe the picture that was being displayed. The summed score on the screener items ranged from 0 to 5. Test–retest reliability of the EVT-2 is good (0.79; Reese & Read, 2000) and it is validated for use with adults with and without intellectual disabilities (Cascella, 2006).

5.3.4 |. Multidimensional scale of perceived social support

The MSPSS (Zimet et al., 1988; Appendix A) is a 12-item instrument used to measure perceived social support from three sources: SO (items 1, 2, 5, and 10), FAM (items 3, 4, 8, and 11), and FRI (items 6, 7, 9, and 12). Each item on the MSPSS was rated on a 7 point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). A total score can be calculated by summing responses for all 12 items. Subscale scores can also be obtained by summing responses to items in each of the three subscales. Possible scores on each subscale range from 4 to 28 while the full scale score can range from 12 to 84. Higher scores on the MSPSS represent individuals with higher levels of perceived social support.

5.3.5 |. Demographics

The following demographic variables were collected: Age, gender (man vs. woman), marital status (single or never married vs. married or living with a partner before incarceration), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic), race (White, Black, Native-American/Alaskan, Asian, or other), employment status (employed vs. unemployed), length of time served, and length of sentence.

5.4 |. Statistical analysis

Analyses assessed the factor structure, known groups validity, convergent and discriminant validity, and interrater reliability of the MSPSS in our sample. In the absence of a true criterion or gold standard upon which a measure can be assessed to establish criterion-based validity, construct validity, that is, the degree to which an instrument measures the underlying construct that it was designed to measure (Porta, 2008), can be established through assessment of known-groups validity and convergent and discriminant validity (Fayers & Machin, 2000). Therefore, overall validity was represented by known-groups, convergent, and discriminant validity.

First, the means (standard deviation [SD]), medians (interquartile range [IQR]), and frequency distributions of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of study participants were tabulated. We used mean (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, medians (IQR) for non-normally distributed continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality indicated that UCLA LS scores were normally distributed. Age, MSPSS, and EVT-2 scores were not normally distributed.

5.4.1 |. Factor structure

First, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the MSPSS. We conducted CFA using maximum likelihood estimation approaches. Post-estimation goodness of fit indices (i.e., root mean square of approximation [RMSEA], comparative fit index [CFI], and standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR]) were used to assess model fit. The criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Brown (2014) were used to assess goodness of fit: (a) SRMR values <0.08; (b) RMSEA values = 0.06 or below; and (c) CFI/Tuckers–Lewis index (TLI) values >0.95. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All p values are two-sided and set to α = 0.05. Confirming the MSPSS factor structure among incarcerated adults would support its use for the population.

5.4.2 |. Known-groups validity

Prior research suggests that measures of social support obtained with the MSPSS vary depending on gender and marital status (Berg & Huebner, 2011; Eker et al., 2001). We also hypothesized that social support scores for incarcerated adults in the study would vary depending on the severity of their current MDE (lower for more severe MDE), gender (higher for women), and marital status (higher for individuals who are married). This finding would be an indicator that the MSPSS performs similarly among incarcerated adults as it does in other populations. As MSPSS scores were not normally distributed, we calculated the median (IQR) MSPSS scores overall and for the SO, FAM, and FRI subscales by incarcerated adults’ gender (men vs. women), marital status (single or never married vs. married or living with a partner before incarceration) and current MDE severity (non-severe vs. severe MDE). We then conducted statistical tests (Mann–Whitney tests) to determine whether there were significant differences at p < .05 in overall MSPSS and subscale scores by each of the three dichotomous variables.

5.4.3 |. Convergent and discriminant validity

Next, we evaluated the MSPSS using standard measures of convergent and discriminant validity. Assuring that the MSPSS is correlated with the expected constructs and uncorrelated with irrelevant other constructs demonstrates that it functions as expected for individuals who are incarcerated. We tested the convergent and discriminant validity of the full MSPSS and then the convergent and discriminant validity of the MSPSS scale items. For the full scale, we assessed the Pearson correlation coefficient between the MSPSS and UCLA LS scores (assuming bivariate normality) and Spearmanʼs correlation coefficient between MSPSS and EVT-2 scores (because we could not assume bivariate normality). We hypothesized that the MSPSS score would be correlated with the UCLA LS score but not correlated with the EVT-2 score. Since social support and loneliness are related constructs (Chen & Feeley, 2014), a strong correlation (≥0.50) between the MSPSS and UCLA LS score would be a strong indicator of convergent validity. A weak correlation (<0.30) between MSPSS scores and EVT-2 scores would signal strong discriminant validity since the two constructs are not known to be closely connected. We also assessed the convergent and discriminant validity of the individual MSPSS scale items. To do this, we evaluated the strength of the associations between items using inter-item correlation coefficients (Fayers & Machin, 2000). We tested the inter-correlations for items belonging to the same subscale versus correlations for items belonging to different subscales (Fayers & Machin, 2000). We also used correlation coefficients to measure the direction and strength of item-test, item-rest, and average inter-item correlations. Overall, average inter-item correlations equal to 0.50 with individual inter-item correlations about this value were considered appropriate (Clark & Watson, 1995).

5.4.4 |. Internal consistency reliability

We used Cronbachʼs α values and the composite reliability coefficient to establish the internal consistency reliability of the MSPSS among incarcerated adults. Cronbachʼs α value is used to establish an instrumentʼs internal consistency reliability and measures the correlation between the total score across a series of items on an instrument (e.g., the 12 items on the MSPSS) and the total score that would have been obtained if a comparable series of items had been employed (Porta, 2008). Overall, alpha values and alpha values corrected for overlap ≥0.80 were considered adequate (Clark & Watson, 1995; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1978). Because the underlying measurement model of the MSPSS is also congeneric, we also computed the composite reliability coefficient (Raykov & Shrout, 2002) to supplement Cronbachʼs α measure of internal consistency.

6 |. RESULTS

Participants’ socioeconomic and demographic variables are presented in Table 1. A total of 184 incarcerated adults with median (IQR) age of 39.5 (31, 47) years were included. The majority of participants were male (64.1%; n = 118), Non-Hispanic (81.4%; n = 150) and of White race (63.0%; n = 116). In addition, 22.8% of participants (n = 42) identified as African American or Black. More than half (59.8%; n = 110) of participants reported they had never married, 19.6% (n = 36) identified as divorced or in annulled marriages and 15.2% (n = 28) as married or living with a partner before incarceration. About half (55.7%; n = 102) of participants reported not being employed in the immediate period preceding their imprisonment. Participants had been incarcerated a median of 31 months; 15% were serving life sentences. For participants not serving life sentences, median sentence length was 58–60 months.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics and socioeconomic characteristics

| Characteristic | N = 184 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.3 ± 10.4a |

| Range = 20–61 | |

| Gender | |

| Man | 118 (64.1%)a |

| Woman | 66 (35.9%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 34 (18.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 149 (81.4%) |

| Raceb | |

| White | 116 (63.0%) |

| African American or Black | 42 (22.8%) |

| Native-American/Alaskan | 10 (5.4%) |

| Asian | 2 (1.1%) |

| Other | 24 (13.0%) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 110 (59.8%) |

| Married or living with a partner | 22 (15.2%) |

| Separated | 7 (3.8%) |

| Divorced or annulled | 36 (19.6%) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.6%) |

| Employment status before incarceration | |

| Not employed | 81 (44.3%) |

| Employed | 102 (55.7%) |

| Time served on current sentence (in months) | Median = 31 (range = 1–489) |

| Life sentence | 27 (15%) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Mean ± SD (standard deviation) or n (%).

Percentages do not add up to 100 as participants identified as more than one race.

6.1 |. Factor structure

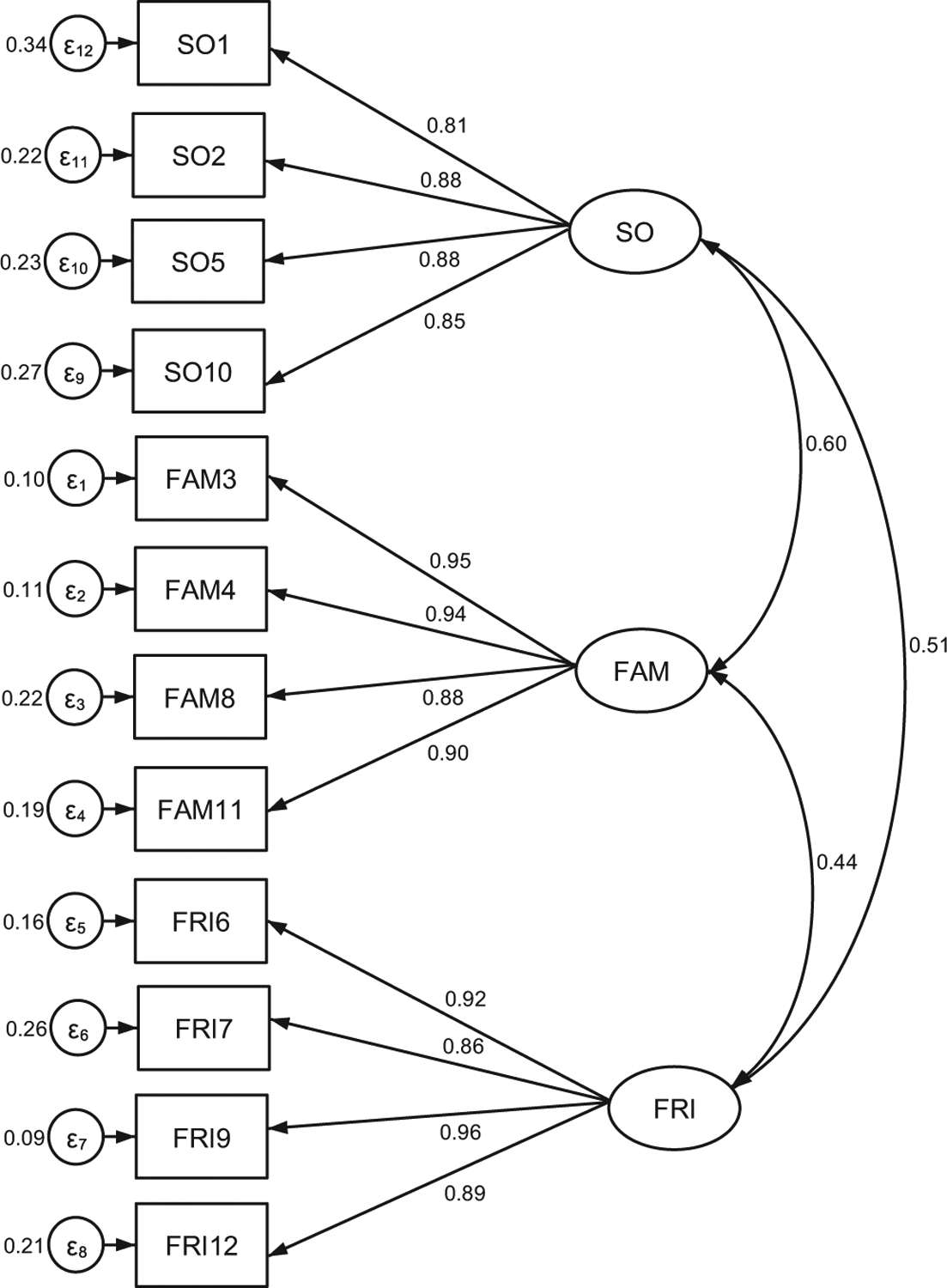

Results from the CFA (Figure 1) showed each of the 12 items loading on its respective factor within the three-factor solution with loadings of 0.81 or greater. The post-estimation goodness of fit indices for the three-factor structure of the MSPSS met all four indices in our a priori set criteria, that is, CFI/TLI > 0.95 and SRMR < 0.08 (Table 2). The observed measures of goodness-of-fit were RMSEA (95% confidence interval [CI]) = 0.09 (0.07; 0.11), CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, and SRMR = 0.03. Interfactor-correlations are shown in Figure 1. Large inter-factor correlations were observed during CFA among all three factors in the solution. The largest inter-factor correlation (0.60) was between the SO and the FAM factors. This was followed by the inter-factor correlation between the SO and FRI factors (0.51). The correlation (0.44) between the FAM and FRI factors was the lowest.

FIGURE 1.

CFA model of the three-factor structure of the MSPSS. CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; FM, family; FRI, friends; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support; SO, significant other

TABLE 2.

Confirmatory factor analyses goodness of fit indices for the MSPSS

| Goodness of fit criteria | Estimate |

|---|---|

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.091 |

| Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) | 0.029 |

| Tuckers–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.955 |

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.965 |

Abbreviation: MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

6.2 |. Known-groups validity

Women in prison scored significantly higher than men in prison on the MSPSS total score (Table 3). Women also had significantly higher scores on the SO, FAM, and FRI subscales. Severe current MDE cases scored significantly lower on the MSPSS than non-severe MDE cases; they also scored lower on the SO, FAM, and FRI subscales. Contrary to our expectation, incarcerated adults who were married or living with a partner before incarceration (n = 22) did not score significantly higher on the full MSPSS than single or never married adults in prison (n = 110). However, married incarcerated adults did score higher on the SO subscale (but not on the FAM or FRI subscales; see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

MSPSS (and subscale) means and standard deviations overall and by gender and marital status of prisoners with MDD

| Social support measure (MSPSS) or subscale | Overall score | Gender | Marital status | Severity of MDEa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Woman | T statistic | Pr (|T| > |t|) | Married | Single | T statistic | Pr (|T| > |t|) | Not severe | Severe | T statistic | Pr (|T| > |t|) | ||

| Overall MSPSS score | 53.0 ± 18.7 | 48.9 ± 18.7 | 60.3 ± 16.4 | 4.1 | 0.00 | 58.5 ± 16.6 | 53.8 ± 18.8 | −1.2 | 0.24 | 56.7 ±18.7 | 49.5 ± 18.1 | −2.6 | 0.01 |

| Significant other (SO) | 19.2 ± 7.4 | 17.7 ±7.7 | 21.8 ± 5.8 | 3.8 | 0.00 | 22.7 ±5.6 | 19.1 ± 7.6 | −2.4 | 0.02 | 20.2 ± 7.4 | 18.2 ± 7.2 | −1.9 | 0.06 |

| Family (FAM) | 18.1 ± 8.2 | 17.2 ± 7.8 | 19.7 ± 8.7 | 2.0 | 0.05 | 19.6 ±7.9 | 18.7 ± 7.9 | −0.6 | 0.58 | 19.6 ± 7.8 | 16.7 ± 8.3 | −2.4 | 0.02 |

| Friend (FRI) | 15.7 ± 7.5 | 14.0 ± 7.3 | 18.8 ± 6.9 | 4.4 | 0.00 | 16.2 ± 7.7 | 16.1 ± 7.5 | −0.04 | 0.97 | 16.8 ± 7.4 | 14.6 ± 7.4 | 2.0 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

Bold indicates significant p value at p < .05.

6.3 |. Convergent and discriminant validity

Analyses assessed whether the MSPSS was correlated with scores on scales measuring related constructs (i.e., UCLA LS measure of loneliness), and uncorrelated with unrelated constructs (i.e., EVT-2 measure of verbal ability). MSPSS total scores were correlated with UCLA LS total scores (r = −.47; p < .01). MSPSS total scores were not correlated with EVT-2 scores (Spearmanʼs rho, ρ = .05, p = .52).

6.4 |. Internal consistency reliability

Associations between individual items on the MSPSS scale were satisfactorily high with the largest inter-item correlations observed for items belonging to the same subscale, that is, 0.62–0.77 for SO; 0.81–0.89 for FAM, and 0.75–0.87 for FRI (Table 4). Inter-item correlations for items belonging to different subscales ranged from 0.33 to 0.57 indicating that the values were above the critical value of 0.30 for all items. The overall average inter-item Spearmanʼs correlation coefficient was 0.52 with individual inter-item correlations ranging between 0.51 and 0.53 (Table 5). With the exception of the MSPSS item 7 (i.e., FRI7. I can count on my friends when things go wrong) which had an item-test correlation coefficient equal to 0.70, all of the other 11 items had item-test correlation coefficients that ranged between 0.72 and 0.80. Values of each of the item-test correlation coefficients were slightly lower than the corresponding item-test correlations.

TABLE 4.

Inter-item correlations for the SO, FAM, and FRI subscales of the MSPSS

| MSPSS subscale and item | SO1 | SO2 | SO5 | SO10 | FAM3 | FAM4 | FAM8 | FAM 11 | FR16 | FR17 | FR19 | FRI12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO | ||||||||||||

| SO1. There is a special person who is around when I am in need | 1 | |||||||||||

| SO2. There is a special person with whom I can share joys and sorrows | 0.76 | 1 | ||||||||||

| SO5. I have a special person who is a source of comfort to me | 0.70 | 0.73 | 1 | |||||||||

| SO10. There is a special person in my life that cares about my feelings | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 1 | ||||||||

| FAM | ||||||||||||

| FAM3. My family really tries to help me | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 1 | |||||||

| FAM4. I get help and support I need from my family | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 1 | ||||||

| FAM8. I can talk about my problems with my family | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 1 | |||||

| FAM11. My family is willing to help me make decisions | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1 | ||||

| FRI | ||||||||||||

| FRI6. My friends really try to help me | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 1 | |||

| FRI7. I can count on my friends when things go wrong | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.83 | 1 | ||

| FRI9. I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 1 | |

| FRI12. I can talk about my problems with my friends | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 1 |

Note: Bold indicates inter-correlations of items in the same subscale.

Abbreviations: FM, family; FRI, friends; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support; SO, significant other.

TABLE 5.

Item-test and item-rest correlation and Cronbachʼs α values of the MSPSS

| MSPSS items | Item-test correlation | Item-rest correlation | Average inter-item correlation | a If item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO | ||||

| SO1. There is a special person who is around when I am in need | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.92 |

| SO2. There is a special person with whom I can share joys and sorrows | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| SO5. I have a special person who is a source of comfort to me | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| SO10. There is a special person in my life that cares about my feelings | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.92 |

| FAM | ||||

| FAM3. My family really tries to help me | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| FAM4. I get help and support I need from my family | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| FAM8. I can talk about my problems with my family | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| FAM11. My family is willing to help me make decisions | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

| FRI | ||||

| FRI6. My friends really try to help me | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.92 |

| FRI7. I can count on my friends when things go wrong | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.93 |

| FRI9. I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.92 |

| FRI12. I can talk about my problems with my friends | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.92 |

| Overall for the MSPSS | 0.52 | 0.93 |

Abbreviations: FM, family; FRI, friends; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support; SO, significant other.

The overall Cronbachʼs α value for the scale was 0.93. Cronbach’s α values for the three subscales were 0.91 for SO, 0.95 for FAM, and 0.95 for FRI. Cronbach’s α values for the entire scale if any of the 12 items were deleted from the scale ranged between 0.92 and 0.93, further indicating strong internal consistency reliability. The composite reliability coefficient for the MSPSS was 0.91 with a 95% CI of 0.89–0.93.

7 |. DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the MSPSS (Appendix A) among U.S. incarcerated adults with MDD. This is the first study to evaluate the performance of MSPSS among incarcerated adults with MDD or among any incarcerated population, despite its use in this context (Brown & Day, 2008; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008; Nargiso et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2010). Results indicate that the MSPSS replicated a stable three-factor structure with indicators of goodness of fit (Figure 1) and demonstrated strong measures of known-groups validity (Table 2), convergent and discriminant validity (Table 3), and internal consistency (Table 4).

The MSPSS factor structure found in other populations held up well for incarcerated adults, suggesting that use of the MSPSS and its subscales is appropriate in this population. Our validation of the MSPSSʼs three-factor structure among incarcerated adults is consistent with prior findings by the originators of the MSPSS (Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet et al., 1990) and additional researchers who evaluated the performance of the MSPSS in other populations and settings (Bruwer et al., 2008; Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Cecil et al., 1995; Dahlem et al., 1991; Eker et al., 2001; Kazarian & McCabe, 1991;Vaingankar et al., 2012), aside from a few exceptions in which the three-factor structure was not found due to cultural differences in relationships with SOs, FAM members, and FRIs (Stanley et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2015).

The MSPSS showed good known groups and convergent and discriminant validity. As expected given findings in other populations (Ekbäck et al., 2013; Jiang & Winfree, 2006; Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet et al., 1990), we found that MSPSS scores were lower for men in prison than women in prison. Although MSPSS scores overall were not lower for single or unmarried incarcerated adults than for married incarcerated adults or incarcerated adults living with someone before incarceration, the SO subscale score was. As has been found in other populations, incarcerated adults with a severe current MDE had lower MSPSS scores than for incarcerated adults with a non-severe current MDE. Further evidence of convergent and discriminant validity was observed through the MSPSSʼs significant negative association with a measure of loneliness (UCLA LS) and non-association with verbal ability (EVT-2). Findings in this study are similar to those reported by Ekbäck et al. (2013), which also supported the three-factor structure.

Items on a scale measuring a unified underlying construct should be homogeneous (Brown, 2014). Because internal consistency reliability reflects the degree to which scale items are related to each other, it is a necessary but insufficient condition for achieving homogeneity. As in other populations (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Ekbäck et al., 2013; Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet et al., 1990), our findings suggest that the MSPSS was internally consistent in the sample of incarcerated adults with MDD. Metrics with high levels of homogeneity achieve moderate inter-item correlations with inter-item correlations for the individual items clustering around the mean value (Green, 1978). In this study, the overall inter-item correlation coefficient was 0.52 with average inter-item correlations for individual items ranging from 0.51 to 0.53. In this sample of incarcerated adults with MDD, the MSPSS achieved strong measures of homogeneity possibly indicating that the scale items as a whole measured a unified construct of perceived social support.

7.1 |. Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the psychometric properties of the MSPSS among an incarcerated population. This study provides support for using the MSPSS to assess the social support of incarcerated adults with MDD, offering a valuable tool for assessing clinical outcomes of IPT. However, it is important to note the limitations of the study. The generalizability of results are limited by including only incarcerated adults with MDD, an incarcerated subpopulation for whom social support is important. The sample consisted of mostly white incarcerated adults in the Northeastern U.S. with different lengths of prison stay. Also, the sample size of 184 falls just under the recommended sample size of 200 for CFA (Kline, 1998).

8 |. CONCLUSION

The MSPSS is a frequently used, brief, psychometrically sound measure of social support that has been used in different contexts and populations. This is the first known evaluation of the psychometric properties of MSPSS in an incarcerated population. Our results indicate that the MSPSS achieved strong measures of construct validity, homogeneity, and a stable three-factor structure among U.S. incarcerated adults with MDD. Given the concordance of our results with the majority of previous studies among healthy and clinical populations, we recommend the MSPSS for clinical and research use among incarcerated populations, especially those with MDD (Johnson et al., 2016).

APPENDIX A.

Instructions:

We are interested in how you feel about the following statements; read each statement carefully; indicate how you feel about each statement

TABLE A1.

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support

| Circle the “1” if you very strongly disagree | Circle the “5” if you mildly agree | ||||||||

| Circle the “2” if you strongly disagree | Circle the “6” if you strongly agree | ||||||||

| Circle the “3” if you mildly disagree | Circle the “7” if you very strongly agree | ||||||||

| Circle the “4” if you are neutral | |||||||||

| 1 | There is a special person who is around when I am in need. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | SO1 |

| 2 | There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | SO1 |

| 3 | My family really tries to help me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FAM3 |

| 4 | I get the emotional help and support I need from my family. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FAM4 |

| 5 | I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | SO5 |

| 6 | My friends really try to help me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FRI6 |

| 7 | I can count on my friends when things go wrong. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FRI7 |

| 8 | I can talk about my problems with my family. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FAM8 |

| 9 | I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FRI9 |

| 11 | There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | SO10 |

| 11 | My family is willing to help me make decisions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FAM11 |

| 12 | I can talk about my problems with my friends. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | FRI12 |

Abbreviations: FM, family; FRI, friends; SO, significant other.

REFERENCES

- Bales WD, & Mears DP (2008). Inmate social ties and the transition to society: Does visitation reduce recidivism? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45, 287–321. [Google Scholar]

- Berg MT, & Huebner BM (2011). Reentry and the ties that bind: An examination of social ties, employment, and recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 28, 382–410. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, & Day A (2008). The role of loneliness in prison suicide prevention and management. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 47, 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer B, Emsley R, Kidd M, Lochner C, & Seedat S (2008). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in youth. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty-Mitchell J, & Zimet GD (2000). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascella PW (2006). Standardized speech-language tests and students with intellectual disability: A review of normative data. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 31, 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil H, Stanley MA, Carrion PG, & Swann A (1995). Psychometric properties of the MSPSS and NOS in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Feeley TH (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the health and retirement study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Christian J (2005). Riding the bus: Barriers to prison visitation and family management strategies. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- De Claire K, & Dixon L (2017). The effects of prison visits from family members on prisonersʼ well-being, prison rule breaking, and recidivism: A review of research since 1991. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 18, 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, & Watson D (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7, 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran JC (2014). Breaches in the wall: Imprisonment, social support, and recidivism. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51, 200–229. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen FT (1994). Social support as an organizing concept for criminology: Presidential address to the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Justice Quarterly, 11, 527–559. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem NW, Zimet GD, & Walker RR (1991). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR (2004). Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 23, 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbäck M, Benzein E, Lindberg M, & Årestedt K (2013). The Swedish version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS)—a psychometric evaluation study in women with hirsutism and nursing students. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eker D, Arkar H, & Yaldız H (2001). Factorial structure, validity, and reliability of revised form of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 12, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fayers PM, & Machin D (2000). Multi-item scales. Quality of Life: Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation, 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, & Danesh J (2002). Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: A systematic review of 62 surveys. The Lancet, 359, 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaster DJ, Reznick OG, Zack B, McCartney K, Gregorich SE, & Brincks AM (2013). Health status, sexual and drug risk, and psychosocial factors relevant to postrelease planning for HIV+ prisoners. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 19, 278–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JB (2002). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition.(SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Green BF (1978). In defense of measurement. American Psychologist, 33, 664–670. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1980). Rating depressive patients. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 41, 21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, & Glaze LE (2006). Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, & Winfree LT Jr, (2006). Social support, gender, and inmate adjustment to prison life: Insights from a national sample. The Prison Journal, 86, 32–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Knight K, Simpson DD, Flynn PM, Morey JT, Bartholomew NG, & O’Connell DJ (2012). An evaluation of six brief interventions that target drug-related problems in correctional populations. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 51, 9–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Esposito-Smythers C, Miranda R Jr, Rizzo CJ, Justus AN, & Clum G (2011). Gender, social support, and depression in criminal justice-involved adolescents. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55, 1096–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Miller TR, Stout RL, Zlotnick C, Cerbo LA, Andrade JT, & Wiltsey-Stirman S (2016). Study protocol: Hybrid Type I cost-effectiveness and implementation study of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for men and women prisoners with major depression. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 47, 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Stout RL, Miller TR, Zlotnick C, Cerbo LA, Andrade JT, & Wiltsey-Stirman S (2019). Randomized cost-effectiveness trial of group interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for prisoners with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87, 392–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Williams C, & Zlotnick C (2015). Development and feasibility of a cell phone-based transitional intervention for women prisoners with comorbid substance use and depression. The Prison journal, 95, 330–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, & Zlotnick C (2008). A pilot study of group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in substance-abusing female prisoners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34, 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, & Zlotnick C (2012). Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46, 1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, Glaze L, Tsoutis A, & Minton T (2015). Correctional populations in the United States, 2014. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Kazarian SS, & McCabe SB (1991). Dimensions of social support in the MSPSS: Factorial structure, reliability, and theoretical implications. Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Keller M (2003). Past, present, and future directions for defining optimal treatment outcome in depression: Remission and beyond. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3152–3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, & Cronin A (2008). Low social support and major depression: Research, theory, and methodological issues. In Dobson KS & Dozois DJA (Eds.), Risk factors in depression (pp. 385–408). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N (1986). Conceptualizing social support. In Lin N, Dean A & Ensel WM (Eds.), Social support, life events, and depression (pp. 17–30). Orlando, FL: Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz JD & Markowitz JC (2013). Mechanisms of change in interpersonal therapy (IPT). Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 1134–1147. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano L, Hawton K, Rivlin A, & Fazel S (2011). Psychosocial influences on prisoner suicide: A case-control study of near-lethal self-harm in women prisoners. Social Science and Medicine, 72, 874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Vander Stoep A, Kuo ES, & McCauley E (2006). Depressive symptoms among delinquent youth: Testing models of association with stress and support. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 28, 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargiso JE, Kuo CC, Zlotnick C, & Johnson JE (2014). Social support network characteristics of incarcerated women with co-occurring major depressive and substance use disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46, 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser RL, & La Vigne NG (2006). Family support in the prisoner reentry process: Expectations and realities. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 43, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, & Murrell SA (1990). Social support, life events, and stress as modifiers of adjustment to bereavement by older adults. Psychology and Aging, 5, 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, & Bernstein IH (1978). Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Porta M (Ed.). (2008). A dictionary of epidemiology. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potts MK (1997). Social support and depression among older adults living alone: The importance of friends within and outside of a retirement community. Social Work, 42, 348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins SJ (2014). Prevalence of mental illnesses in U.S. state prisons: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 65, 862–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T, & Shrout PE (2002). Reliability of scales with general structure: Point and interval estimation using a structural equation modeling approach. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, & Read S (2000). Predictive validity of the New Zealand MacArthur communicative development inventory: Words and sentences. Journal of Child Language, 27, 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin A, Hawton K, Marzano L, & Fazel S (2013). Psychosocial characteristics and social networks of suicidal prisoners: Towards a model of suicidal behaviour in detention. PLoS One, 8, e68944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JY, & Kressel D (2005). Measuring client progress in treatment: The client assessment inventory (CAI). CJ-DATS Steering Committee Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer DR, Bouchard M, Young JT, & Kreager DA (2017). Friends in locked places: An investigation of prison inmate network structure. Social Networks, 51, 88–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Beck JG, & Zebb BJ (1998). Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging and Mental Health, 2, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29, 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, & Chong SA (2012). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BB, Miraglia R, Sawyer DA, Beer R, & Eddy J (2005). Factors related to suicide in New York state prisons. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 28, 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE (2000). Interpersonal psychotherapy for group. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Grabiner VE, Zhou Y, & Li N (2010). Suicidal ideation and its correlates in prisoners. Crisis, 31, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Li H, Wei X, Yin J, Liang P, Zhang H, & Zhuang G (2015). Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, & Farley GK (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, & Berkoff KA (1990). Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, & Dalrymple K (2013). Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150, 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]