Abstract

Purpose

Supraphysiologic serum estradiol levels may negatively impact the likelihood of conception and live birth following IVF. The purpose of this study is to determine if there is an association between serum estradiol level on the day of progesterone start and clinical outcomes following programmed frozen blastocyst transfer cycles utilizing oral estradiol.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study at an academic fertility center analyzing 363 patients who underwent their first autologous single (SET) or double frozen embryo transfer (DET) utilizing oral estradiol and resulting in blastocyst transfer from June 1, 2012, to June 30, 2018. Main outcome measures included implantation, clinical pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates. Cycles were stratified by quartile of serum estradiol on the day of progesterone start and separately analyzed for SET cycles only. Poisson and Log binomial regression were used to calculate relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for implantation, clinical pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage with adjustments made for age and BMI.

Results

Cycles with the highest quartile of estradiol (mean 528 pg/mL) were associated with lower risks of implantation (RR 0.66, CI 0.50–0.86), ongoing pregnancy (RR 0.66, CI 0.49–0.88), and live birth (RR 0.70, CI 0.52–0.94) compared with those with the lowest estradiol quartile (mean 212 pg/mL). Similar findings were seen for analyses limited to SETs. There was no significant difference in miscarriage rate or endometrial thickness between groups.

Conclusion

High levels of serum estradiol on the day of progesterone start may be detrimental to implantation, pregnancy, and live birth following frozen blastocyst transfer.

Keywords: Estradiol level, Frozen embryo transfer, Programmed FET, Supraphysiologic estradiol, Oral estradiol

Introduction

Supraphysiologic serum estradiol levels may negatively impact the likelihood of conception and live birth in pregnancies resulting from assisted reproductive technology [1–6]. While existing data are mixed, there is evidence to support a detrimental effect of elevated estradiol levels resulting from controlled ovarian hyperstimulation on outcomes following fresh embryo transfers, likely due to endometrium/embryo asynchrony and/or abnormal trophoblast invasion [7–12]. Several studies have demonstrated poorer IVF outcomes with increasing serum estradiol levels around the time of fresh embryo transfer in a dose-dependent manner, with the suggestion that there may be an “ideal” level of serum estradiol that supports implantation and ongoing pregnancy [3, 7, 13].

Possible etiologies for poorer IVF outcomes include an estradiol-mediated unfavorable effect on endometrial receptivity, aberrant trophoblastic invasion at the time of implantation, and/or a negative impact on oocyte or embryo quality [14–19]. As such, many IVF programs have adopted a freeze-all strategy with subsequent frozen embryo transfers, in lieu of fresh IVF transfers, to mitigate the impact of elevated estradiol [10, 16, 20]. However, the thresholds at which elevated estradiol levels may adversely affect IVF outcomes have not yet been elucidated.

While serum estradiol levels are generally lower at the time of a frozen embryo transfer (FET) than a fresh embryo transfer, it is important to evaluate whether elevated estradiol thresholds may similarly impact outcomes following FET cycles. For programmed (medicated) FET cycles, there are multiple options for the route of estradiol administration, and several studies have demonstrated that administration route does not influence FET cycle outcomes [21–24]. Oral estradiol is commonly used for endometrial preparation and suppression of folliculogenesis [25]. However, in contrast to vaginal and transdermal estradiol administration, oral estradiol is affected by the first pass effect and is largely converted to estrone [26]. Estrone has different effects on the endometrium and measured serum steroid levels differ compared with estradiol; therefore, FET cycles utilizing oral estradiol are intrinsically distinct from cycles utilizing alternate routes of estradiol administration.

Few heterogeneous studies have looked specifically at whether serum estradiol level is associated with outcomes following blastocyst embryo transfer in programmed FET cycles, and have found mixed results. While a study by Fritz et al. has suggested that elevated mean estradiol levels in programmed FET cycles were associated with lower pregnancy and birth rates, other studies have not found estradiol to be associated with pregnancy, live birth, or miscarriage rates following embryo transfer [27–29]. These studies each included cleavage-stage transfers in their analyses, and some utilized non-oral forms of estrogen replacement and/or varying forms of progesterone for luteal support. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to expand on the limited literature and evaluate whether there is an association between serum estradiol level at the time of intramuscular progesterone start and clinical outcomes among frozen blastocyst transfer cycles utilizing oral estradiol.

Materials and methods

Study population

Consecutive autologous single or double frozen blastocyst transfers that were performed between June 1, 2012, and June 30, 2018, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital were retrospectively reviewed after approval from the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 2017P001125). Cycles were included if only oral estradiol was used for endometrial preparation, serum estradiol was drawn on the day of progesterone start, a blastocyst was transferred, and progesterone replacement occurred via the intramuscular route. Only patients’ first frozen blastocyst transfers were included. The exclusion criteria were third-party reproduction cycles, cycles that utilized non-oral routes of estradiol administration, non-intramuscular progesterone administration, GnRH agonist for downregulation, and cycles in which a transferred embryo was previously subjected to preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), as PGT was not routinely utilized in our practice over this study’s timeframe. Patients were excluded if they carried a diagnosis of uterine factor infertility (Asherman’s syndrome, congenital anomalies including unicornuate uterus, innumerable fibroids not amenable to resection, etc.).

Clinical and laboratory protocols

All patients underwent preparation for frozen embryo transfer using exogenous oral estradiol and intramuscular progesterone replacement. Patients had a baseline ultrasound to ensure that there were no functional cysts at the time of cycle start. Oral estradiol was initiated at a dose of 6 mg/day in divided doses in the early follicular phase. Serum estradiol level was checked after 2 or 3 days of administration and the dose increased by 2 mg/day if the level was < 200 pg/mL. A transvaginal ultrasound was performed and serum progesterone level checked between days 14 and 18 of estradiol administration to ensure that the endometrial thickness was ≥ 7 mm and that there was no evidence of ovulation (serum progesterone > 3 ng/mL), based on prior published literature and program experience [30, 31]. If the endometrium was < 7 mm in thickness, either the dose or route of estradiol was modified and serum labs and a transvaginal ultrasound were repeated; patient’s whose route of estradiol was modified were excluded from this study. Intramuscular progesterone (50 mg) was initiated in the evening of laboratory and ultrasound evaluation, 6 days prior to transfer of thawed blastocysts (i.e., the transfer occurred on the 6th day of progesterone administration). The dose of intramuscular progesterone was adjusted if needed to maintain a serum progesterone value of 20 ng/mL or higher. All embryo transfers occurred under direct ultrasound guidance following a trial embryo transfer. Exogenous hormone supplementation was continued until a serum pregnancy test, and if positive, through 10 weeks’ gestation.

Variable collection

Primary study outcomes included implantation, ongoing pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates, using Society of Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) definitions as follows: implantation rate was defined as the number of gestational sacs seen on transvaginal ultrasound following transfer/number of embryos transferred, miscarriage was defined as loss of a previously seen ultrasound-confirmed pregnancy, ongoing pregnancy was defined as an intrauterine gestation beyond 20 weeks, and live birth as the birth of a live fetus. Patient demographics and cycle-specific characteristics were collected from the electronic medical record and included maternal age, BMI, pregnancy and birth history, number of days of estradiol administration, serum estradiol and progesterone levels, SART diagnosis, endometrial thickness, use of ICSI, and number of embryos transferred. Current use of tobacco smoke is an exclusion to treatment at our center.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this study was the live birth rate. Secondary outcomes included implantation, ongoing pregnancy, and miscarriage rates. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables are shown with mean (standard deviation), or median as indicated, with categorical variables described with frequencies (percentage). Cycles were stratified by quartile according to serum estradiol level on the day of progesterone start. Chi-squared tests were used to assess the association between serum estradiol level quartile on the day of progesterone start (exposure) and outcomes following frozen blastocyst transfer (implantation, ongoing pregnancy, miscarriage, and live birth rates). Additionally, regression analyses were performed to calculate crude and adjusted relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses controlled a priori for maternal age at embryo freeze and BMI at time of embryo transfer, and used log binomial regression or Poisson regression when considering the implantation rate for double embryo transfers. Sensitivity analyses were performed considering single embryo transfer cycles only. Blastocyst morphology did not modify results for transfers utilizing SET; as such, blastocyst morphology was not included in the final model, which controlled for maternal age and BMI. Effect estimates excluding 1.0 in the CI denoted statistically significant findings. Statistical significance was assumed for p < 0.05.

Results

Three hundred sixty-three first autologous single or double frozen blastocyst transfer cycles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Baseline population demographics and cycle characteristics are found in Table 1 and stratified by serum estradiol quartile. Serum estradiol levels on the day of intramuscular progesterone start ranged from 135 to 3867 pg/mL. The mean estradiol levels for the lowest quartile were 212 pg/mL and highest quartile was 528 pg/mL. Endometrial thickness was similar across all quartiles with means ranging from 9.1 to 10.0 mm. Age at embryo transfer was similar between groups (mean range: 34.5 to 35.3 years) and the majority of patients were nulliparous across all quartiles. The mean BMI of patients in this cohort was in the overweight category, 25.8 kg/m2. Approximately half of cycles utilized ICSI for fertilization. The majority of patients had not previously had a prior fresh transfer (n = 258, 71.1) and history of prior fresh transfer was not statistically different across estradiol quartiles (p = 0.91). A higher percentage of transfers were single embryo transfers in the group of patients with lower and second serum estradiol quartiles (76.7% and 80.4%) versus the third and highest serum estradiol quartiles (71.4% and 68.9%). The implantation, ongoing pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates for the overall cohort were 58.1%, 50.7%, 48.5%, and 10.2%, respectively.

Table 1.

Population demographics and cycle characteristics of patients who underwent their first autologous single or double frozen embryo transfer utilizing oral estradiol and resulting in blastocyst transfer

| Quartiles of serum estradiol (pg/mL) on day of intramuscular progesterone start | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest N = 90 |

Second N = 92 |

Third N = 91 |

Highest N = 90 |

p-value* | |

|

Serum estradiol level (pg/mL) (mean (SD)) min–max |

212 (29) 135–246 |

274 (16) 247–302 |

340 (21) 304–376 |

528 (385) 378–3867 |

|

| Age (y) at embryo creation (mean (SD)) | 35.3 (4.0) | 35.0 (3.9) | 34.5 (4.0) | 35.2 (3.8) | 0.37 |

| Age category: | 0.14 | ||||

|

< 35y 35–37y 38–40y 41–42y ≥ 43y |

41 (45.6%) 20 (22.2%) 24 (26.7%) 3 (3.3%) 2 (2.2%) |

47 (51.1%) 20 (21.7%) 20 (21.7%) 5 (5.4%) 0 (0.0%) |

53 (58.2%) 23 (25.3%) 10 (11.0%) 2 (2.2%) 3 (3.3%) |

43 (47.8%) 22 (24.4%) 24 (26.7%) 1 (1.1%) 0 (0.0%) |

|

| Age (y) at embryo transfer (mean (SD)) | 36.2 (3.9) | 35.6 (4.0) | 35.1 (3.9) | 35.7 (4.1) | 0.24 |

| Age category: | 0.03 | ||||

|

< 35y 35–37y 38–40y 41–42y ≥ 43y |

33 (36.7%) 23 (25.6%) 26 (28.9%) 3 (3.33%) 5 (5.6%) |

39 (42.4%) 24 (26.1%) 21 (22.8%) 8 (8.7%) 0 (0.0%) |

54 (52.8%) 24 (27.3%) 14 (15.4%) 1 (1.1%) 4 (4.4%) |

40 (44.4%) 17 (18.9%) 28 (31.1%) 4 (4.4%) 1 (1.1%) |

|

| BMI at embryo transfer (kg/m2) (mean (SD)) | 25.4 (6.8) | 26.1 (6.4) | 26.5 (6.2) | 25.0 (5.5) | 0.26 |

| BMI category at embryo transfer | 0.43 | ||||

|

18–24.9 (normal weight) 25.0–29.9 (overweight) 30–34.9 (class I obesity) 35–39.9 (class II obesity) ≥ 40 (class III obesity) |

62 (68.9%) 12 (13.3%) 8 (8.9%) 4 (4.4%) 4 (4.4%) |

50 (54.4%) 21 (22.8%) 8 (8.7%) 8 (8.7%) 5 (5.4%) |

51 (56.0%) 19 (20.9%) 10 (11.0%) 9 (9.9%) 2 (2.2%) |

54 (60.0%) 20 (22.2%) 11 (12.2%) 2 (2.2%) 3 (3.3%) |

|

| Null gravidity | 38 (42.2%) | 38 (41.3%) | 38 (41.8%) | 37 (41.1%) | 1.00 |

| Nulliparous | 58 (64.4%) | 63 (68.5%) | 66 (72.5%) | 61 (67.8%) | 0.71 |

| Diagnosis | |||||

|

Unexplained Male factor Tubal factor Ovulatory dysfunction/PCOS Diminished ovarian reserve Endometriosis Other |

34 (37.8%) 26 (28.9%) 7 (7.8%) 8 (8.9%) 9 (10.0%) 3 (3.3%) 17 (18.9%) |

34 (37.0%) 28 (30.4%) 11 (12.0%) 11 (12.0%) 9 (9.8%) 6 (6.5%) 17 (18.5%) |

33 (36.3%) 33 (36.3%) 5 (5.5%) 10 (11.0%) 14 (15.4%) 4 (4.4%) 20 (22.0%) |

32 (35.6%) 38 (42.2%) 8 (8.9%) 15 (16.7%) 9 (10.0%) 8 (8.9%) 6 (6.7%) |

0.99 0.22 0.47 0.43 0.57 0.39 0.03 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) level on day of mapping (mean (SD)) | 0.31 (0.20) | 0.35 (0.28) | 0.30 (0.21) | 0.39 (0.25) | 0.04 |

| Any prior fresh embryo transfers | 27 (30.0%) | 24 (26.1%) | 28 (30.8%) | 26 (28.9%) | 0.91 |

| Single blastocyst transfer | 69 (76.7%) | 74 (80.4%) | 65 (71.4%) | 62 (68.9%) | 0.28 |

| Number of days of E2 administration at transfer (mean (SD)) | 20.8 (2.9) | 21.2 (3.9) | 21.6 (4.2) | 21.4 (3.4) | 0.85 |

| ICSI (yes) | 49 (54.4%) | 45 (48.9%) | 47 (51.7%) | 51 (56.7%) | 0.74 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) (mean (SD)) | 9.7 (2.5) | 10.0 (2.7) | 9.6 (2.1) | 9.1 (2.6) | 0.07 |

*Continuous variables (e.g., age, BMI, progesterone level) were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis tests and categorical variables (e.g., age category, diagnosis, null gravity, nulliparity) were analyzed using chi-squared tests

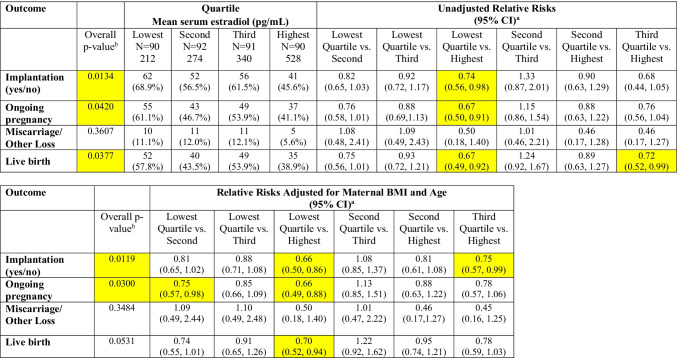

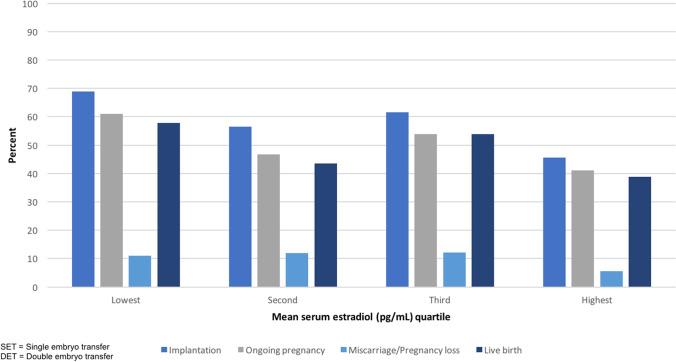

Clinical outcomes when combining single and double embryo transfers are shown in Table 2 and visually represented in Fig. 1. There was a statistically significant difference across quartiles of serum estradiol for implantation and ongoing pregnancy (p-values = 0.01 and 0.03, respectively, in the adjusted models). We observed a statistically significant difference in the unadjusted models for live birth across quartiles (p = 0.04), which attenuated slightly and no longer reached the threshold of statistical significance in confounder-adjusted models (p = 0.053). The unadjusted and adjusted risks of implantation were significantly lower when serum estradiol was in the top quartile (> 75%; mean estradiol 528 pg/mL) compared with the lowest quartile (referent value < 25%; mean estradiol 212 pg/mL; unadjusted and adjusted RR (CI): 0.74 (0.56–0.98) and 0.66 (0.50–0.86), respectively. The risks of ongoing pregnancy and live birth were similarly lower for the highest vs. lowest quartile in both unadjusted and adjusted models (adjusted RR (CI) for live birth: 0.70 (0.52–0.94). There was no difference in the risk of miscarriage between groups.

Table 2.

Differences in outcomes by estradiol quartile—all single and double embryo transfers (N = 363)

aFirst category is reference category for calculation of crude and adjusted relative risks, as noted

bChi-squared test

Fig. 1.

Differences in frozen embryo transfer outcomes by mean serum estradiol quartile for single and double embryo transfers

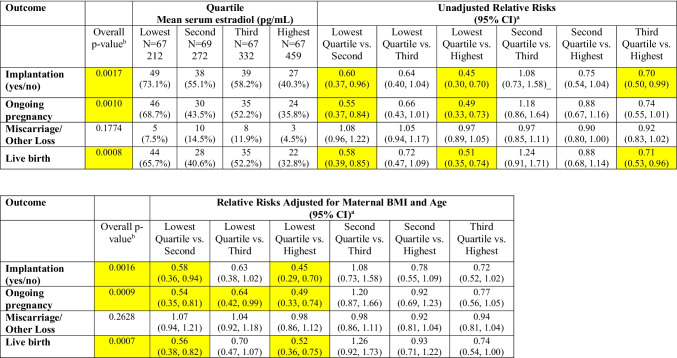

Analyses that considered only single embryo transfers demonstrated similar findings, with overall p-values indicating statistically significant differences across quartiles for implantation, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth in both unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 3). Cycles with estradiol levels in the highest quartile (mean 459 pg/mL) versus lowest quartile (mean 212 pg/mL) were associated with significantly lower risks of implantation (RR (CI): 0.45 (0.29–0.70)), ongoing pregnancy (RR (CI): 0.49 (0.33–0.74)), and live birth (RR (CI): 0.52 (0.36–0.75)) in the adjusted models. Similarly, serum estradiol levels in the second quartile (mean 272 pg/mL) versus the lowest quartile were associated with lower risks of implantation, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth. There were no statistically significant differences in miscarriage rates across quartiles.

Table 3.

Differences in outcomes by estradiol quartile—single embryo transfers only (N = 270)

aFirst category is reference category for calculation of crude and adjusted relative risks, as noted

bChi-squared test

Discussion

This study examined the association between serum estradiol levels at the start of progesterone replacement and outcomes following programmed frozen blastocyst transfers. Our results indicate that elevated levels of serum estradiol may negatively impact implantation, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth rates. Analyses including only cycles in which a single embryo was transferred demonstrated similar findings. It is clear that appropriate endometrial preparation is imperative for optimizing embryo transfer outcomes, and that the serum levels of estradiol and progesterone, as well as the interaction between these steroid hormones, may play critical roles in implantation [32, 33]. While there was not a direct linear relationship between estradiol level and IVF outcomes on the day of progesterone start, there may instead be a “threshold” estradiol level above which outcomes are poorer, as suggested by our results, with the poorest outcomes associated with the highest estradiol values.

The percentage of embryo transfers performed using frozen/warmed blastocysts is increasing. There are several possible explanations for this, including better ovarian stimulation and freezing techniques, the increased utilization of PGT and single embryo transfer, and the concern that supraphysiologic serum estradiol levels at the time of oocyte stimulation may negatively impact outcomes following fresh embryo transfer [1, 2, 10, 16, 20]. Serum estradiol levels during frozen embryo transfer cycles are lower, on average, than serum estradiol levels at the time of a fresh embryo transfer, potentially mitigating the detrimental impact of elevated estradiol reported in fresh stimulation cycles. However, even during programmed frozen embryo transfer cycles, serum estradiol levels can vary greatly and are often supraphysiologic compared with levels normally seen in natural ovulatory cycles. In this present study, the top decile of serum estradiol was 697 pg/mL. Whether these estradiol values around the time of implantation influence frozen cycle success has been debated in the literature.

A study by Fritz et al. demonstrated similar findings to our results, in which elevated mean estradiol levels in programmed FET cycles were associated with lower pregnancy and birth rates [27]. Among their 110 cycles analyzed, they found a statistically significant downward trend in pregnancy and live birth rates with increasing estradiol levels, though peak estradiol levels during FETs were not significantly different between cycles resulting in pregnancy or live birth versus unsuccessful cycles. Their study differs from ours in the heterogeneity of the cycles studied, which included both cleavage-stage and blastocyst-stage embryo transfers; utilization of transdermal, intramuscular, and vaginal estradiol; and intramuscular or vaginal progesterone, all of which are potential confounding variables that may impact cycle outcomes [34]. Despite differences in study design, the consistent findings of the two studies suggest that elevated estradiol levels may pose a detriment to success following programmed frozen embryo transfer cycles.

The findings of our study differ from several prior studies, though differences in methodology make direct comparisons challenging. A study by Niu et al., which evaluated 274 frozen embryo transfers of cleavage-stage blastocysts, found that serum estradiol was not predictive of cycle success [28]. However, pregnancy rates were lower than in our study (approximately 40% for all cycles) and the top quartile of serum estradiol level was < 300 pg/mL. This may suggest that higher estradiol levels are needed to detect a detrimental effect, as seen in our study. Similar to our study, the authors found that endometrial thickness was not directly related to serum estradiol level. Our results are also in contrast to a larger retrospective study by Mackens et al., who analyzed outcomes of 1222 programmed FET cycles according to serum estradiol level on the day of progesterone start and found no statistically significant differences in live birth rate across groups [29]. However, live birth rates in this study were much lower than in our study (range: 17.4% (for cycles with highest estradiol levels) to 25.0% (for cycles with the lowest estradiol levels)) and at least 30% of cycles for each estradiol stratification consisted of a cleavage-stage embryo transfer.

Strengths of our study include that all transfers were of warmed blastocysts and the estradiol and progesterone administration route was consistent across all cycles, eliminating potential biases. Analyses were completed for both single and double embryo transfers, and results were confirmed with analyses of single embryo transfers alone, controlling for confounding variables. Study limitations include the retrospective study design and relatively small N for each quartile, though consistent with prior studies. Analyses restricted to SETs similarly have a smaller sample size. As estradiol level was only measured twice during the cycle, once after 2–3 days of estradiol administration (around cycle day 4), and one additional time between cycle day 14 and 18, mean serum estradiol cannot accurately be determined. The population studied was limited to one clinical setting in Massachusetts, which may limit generalizability.

In summary, elevated levels of serum estradiol on the day of progesterone start decreased implantation, pregnancy, and live birth rates following frozen blastocyst transfer in programmed cycles. As serum estradiol level is a potentially modifiable variable, determining an “ideal” estradiol value may improve overall success rates. Further study on the underlying mechanisms by which elevated estradiol may negatively impact outcomes following FET should be undertaken.

Author contribution

Mark Hornstein and Randi Goldman formulated the study questions and directed their implementation. Leslie Farland and Catherine Racowsky contributed to the study design. Leslie Farland, Ann Muir Thomas, and Andrea Lanes performed statistical analyses. Catherine Racowsky and Anna Greer provided critical data. All authors were involved with data interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Randi Goldman, Anna Greer, and Mark Hornstein. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript and have approved this final version.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 2017P001125). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

MH is on the advisory board for WIN Fertility and Interlon Optics and is an author on Up-To-Date, all outside the submitted work. RG is an editorial board member for the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Forman R, Fries N, Testart J, Belaisch-Allart J, Hazout A, Frydman R. Evidence for an adverse effect of elevated serum estradiol concentrations on embryo implantation. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:118–122. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simón C, Cano F, Valbuena D, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Clinical evidence for a detrimental effect on uterine receptivity of high serum oestradiol concentrations in high and normal responder patients. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2432–2437. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joo BS, Park SH, An BM, Kim KS, Moon SE, Moon HS. Serum estradiol levels during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation influence the pregnancy outcome of in vitro fertilization in a concentration-dependent manner. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitwally MFM, Bhakoo HS, Crickard K, Sullivan MW, Batt RE, Yeh J. Estradiol production during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation correlates with treatment outcome in women undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steward RG, Zhang CE, Chen C, Li Y-J, Price TM, Muasher SJ. High peak estradiol (E2) predicts higher miscarriage (MC) and lower live birth (LB) rates in high-responders triggered with a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) in IVF/ICSI cycles. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:S139–S140. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.1571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandoval JS, Steward RG, Chen C, Li YJ, Price TM, Muasher SJ. High peak estradiol/mature oocyte ratio predicts lower clinical pregnancy, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth rates in GnRH antagonist intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imudia AN, Goldman RH, Awonuga AO, Wright DL, Styer AK, Toth TL. The impact of supraphysiologic serum estradiol levels on peri-implantation embryo development and early pregnancy outcome following in vitro fertilization cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelety TJ, Buyalos RP. The influence of supraphysiologic estradiol levels on human nidation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1995;12:406–412. doi: 10.1007/BF02211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imudia AN, Awonuga AO, Doyle JO, Kaimal AJ, Wright DL, Toth TL, et al. Peak serum estradiol level during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation is associated with increased risk of small for gestational age and preeclampsia in singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1374–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinerman R, Mainigi M. Why we should transfer frozen instead of fresh embryos: the translational rationale. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng EHY, Yeung WSB, Lau EYL, So WWK, Ho PC. High serum oestradiol concentrations in fresh IVF cycles do not impair implantation and pregnancy rates in subsequent frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:250–255. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karatasiou GI, Bosdou JK, Venetis CA, Zepiridis L, Chatzimeletiou K, Tarlatzi TB, et al. Is the probability of pregnancy after ovarian stimulation for IVF associated with serum estradiol levels on the day of triggering final oocyte maturation with hCG? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1531–1541. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01829-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Zeng C, Shang J, Wang S, Gao XL, Xue Q, et al. Association between serum estradiol level on the human chorionic gonadotrophin administration day and clinical outcome. Chin Med J. 2019;132:1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C, Thomas S. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer in normal responders. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Restrepo H, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C. Matched-cohort comparison of single-embryo transfers in fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:389–392. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C. Clinical rationale for cryopreservation of entire embryo cohorts in lieu of fresh transfer. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erşahin AA, Acet M, Erşahin SS, Dokuzeylül GN. Frozen embryo transfer prevents the detrimental effect of high estrogen on endometrium receptivity. J Turkish German Gynecol Assoc. 2017;18:38–42. doi: 10.4274/jtgga.2016.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarin JJ, Pellicer A. Consequences of high ovarian response to gonadotropins: a cytogenetic analysis of unfertilized human oocytes. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:665–670. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)53827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valbuena D, Martin J, De Pablo JL, Remohí J, Pellicer A, Simón C. Increasing levels of estradiol are deleterious to embryonic implantation because they directly affect the embryo. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:962–968. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biliangady R, Pandit R, Tudu N, Kinila P, Maheswari U, Gopal I, et al. Is it time to move toward freeze-all strategy? - A retrospective study comparing live birth rates between fresh and first frozen blastocyst transfer. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2019;12:321–326. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_146_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davar R, Janati S, Mohseni F, Khabazkhoob M, Asgari S. A comparison of the effects of transdermal estradiol and estradiol valerate on endometrial receptivity in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a randomized clinical trial. J Reprod Infertil. 2016;17:97–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao X, Li Z, Dong X, Zhang H. Comparison between oral and vaginal estrogen usage in inadequate endometrial patients for frozen-thawed blastocysts transfer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:6992–6997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corroenne R, El Hachem H, Verhaeghe C, Legendre G, Dreux C, Jeanneteau P, et al. Endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer in an artificial cycle: transdermal versus vaginal estrogen. Sci Rep. 2020;10:985. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57730-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garimella S, Karunakaran S, Gedela DR. A prospective study of oral estrogen versus transdermal estrogen (gel) for hormone replacement frozen embryo transfer cycles. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37:515–518. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2020.1793941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weissman A, Leong M, Sauer MV, Shoham Z. Characterizing the practice of oocyte donation: a web-based international survey. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madero S, Rodriguez A, Vassena R, Vernaeve V. Endometrial preparation: effect of estrogen dose and administration route on reproductive outcomes in oocyte donation cycles with fresh embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1755–1764. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fritz R, Jindal S, Feil H, Buyuk E. Elevated serum estradiol levels in artificial autologous frozen embryo transfer cycles negatively impact ongoing pregnancy and live birth rates. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:1633–1638. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu Z, Feng Y, Sun Y, Zhang A, Zhang H. Estrogen level monitoring in artificial frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles using step-up regime without pituitary suppression: is it necessary? J Exp Clin Assist Reprod. 2008;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-1050-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackens S, Santos-Ribeiro S, Orinx E, De Munck N, Racca A, Roelens C, et al. Impact of serum estradiol levels prior to progesterone administration in artificially prepared frozen embryo transfer cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:255. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro D, Boostanfar R, Silverberg K, Yanushpolsky EH. Examining the evidence: progesterone supplementation during fresh and frozen embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29:S1–S14. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(14)50063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasius A, Smit JG, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJC, Mol BW, Opmeer BC, et al. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:530–541. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labarta E, Mariani G, Holtmann N, Celada P, Remohí J, Bosch E. Lower serum progesterone on the day of embryo transfer is associated with a diminished ongoing pregnancy rate in oocyte donation cycles after artificial endometrial preparation: a prospective study. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2437–2442. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rashid NA, Lalitkumar S, Lalitkumar PG, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Endometrial receptivity and human embryo implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Correia KF, Dodge LE, Farland LV, Hacker MR, Ginsburg E, Whitcomb BW, Wise LA, Missmer SA. Confounding and effect measure modification in reproductive medicine research. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1013–1018. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]