Abstract

The diamines putrescine, cadaverine, and diaminopropane stimulate cephamycin biosynthesis in Nocardia lactamdurans, in shake flasks and fermentors, without altering cell growth. Intracellular levels of the P7 protein (a component of the methoxylation system involved in cephamycin biosynthesis) were increased by diaminopropane, as shown by immunoblotting studies. Lysine-6-aminotransferase and piperideine-6-carboxylate dehydrogenase activities involved in biosynthesis of the α-aminoadipic acid precursor were also greatly stimulated. The diamine stimulatory effect is exerted at the transcriptional level, as shown by low-resolution S1 protection studies. The transcript corresponding to the pcbAB gene and to a lesser extent also the lat transcript were significantly increased in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures, whereas transcription from the cefD promoter was not affected. Coupling of the lat and pcbAB promoters to the reporter xylE gene showed that expression from the lat and pcbAB promoters was increased by addition of diaminopropane in Streptomyces lividans. Intracellular accumulation of diamines in Nocardia may be a signal to trigger antibiotic production.

Polyamines are polycationic compounds that have a variety of physiological effects in microorganisms and animal cells. In gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, polyamines have been shown to play an important role in chromosome stabilization by compacting DNA and neutralizing negative charges (28). Polyamines affect the DNA synthesis by increasing the movement rate of the DNA replication fork (29). Furthermore, polyamines also stabilize functional ribosome structures controlling the fidelity of the translation process, including specific steps such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis, binding, and initiation or elongation of the polypeptide chain (24). These compounds also appear to have a critical function in membrane stability, suggested by their ability to decrease the lysis of spheroplasts and protoplasts diluted in hypotonic media (30).

The molecule of cephamycin C is synthesized in Nocardia lactamdurans from the three precursor amino acids, l-α-aminoadipic acid, l-cysteine, and l-valine, which are initially condensed to form the tripeptide δ-(l-α-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine (lld-ACV) by the large ACV synthetase multienzyme (4, 5). The tripeptide is later cyclized to isopenicillin N (7), and this penicillin intermediate is converted into cephamycin C by a series of late modification reactions (1, 23). The N. lactamdurans genes encoding cephamycin biosynthesis enzymes have been cloned and sequenced and shown to be clustered (6) in a 30-kb region of the genome of this microorganism (22). The genes of the cephamycin cluster are expressed as polycistronic mRNAs from three promoters, latp, pcbABp, and cefDp (11).

Production of cephamycin C by N. lactamdurans has been improved by strain selection and medium optimization. Inamine and Birmbaum (14) claimed in a Merck, Sharp & Dohme patent that cephamycin production in N. lactamdurans is stimulated by diamines, although the mechanism of this stimulation remains unknown.

Positive regulatory factors of antibiotic biosynthesis are of great interest. The diamine effect on cephamycin biosynthesis might be exerted at the transcriptional level, or it might be due to stimulation of the conversion of lysine into α-aminoadipic acid by the action of lysine-6-aminotransferase (5) and piperideine-6-carboxylate (P6C) dehydrogenase (8, 25).

In this article, we provide evidence showing that diaminopropane and other diamines increase the levels of several cephamycin biosynthetic enzymes by inducing transcription of the early cephamycin biosynthetic genes in N. lactamdurans. The inducer effect is clearly observed on transcription from latp and pcbABp, the two early promoters of the cephamycin gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and culture conditions.

N. lactamdurans MA4213, an improved cephamycin C producer strain (Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Rahway, N.J.) was used in this study. Mycelium was kept frozen in 20% glycerol at −20°C. Seed and antibiotic production cultures were grown in complex NYG medium (13). Triple-baffled flasks (500 ml) containing 100 ml of NYG medium were inoculated with 10 ml of a 48-h seed culture in the same medium and incubated at 24.5°C on a rotary shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) at 250 rpm. Batch fermentations were carried out in NYG medium in a Biostat Q fermentor (Braun Biotech, Barcelona, Spain) with four identical vessels of 500 ml. The fermentors, containing 270 ml of NYG medium, were inoculated with 1% (vol/vol) 48-h seed culture and incubated at 24.5°C with stirring at 400 rpm and sparging with air at 0.15 liter/min. Foaming was controlled by addition of antifoam MA24 DF 7960 (Braun Biotech).

In experiments to study the effect exerted by different diamines on antibiotic production, the NYG medium was supplemented with diaminopropane, putrescine, or cadaverine, at concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 g/liter.

Growth was estimated as cell DNA content, using the diphenylamine reagent (2) and salmon sperm DNA standard as described previously (18).

Antibiotic assays.

Cephamycin C was routinely measured by bioassay using the agar diffusion method with E. coli ESS-2231 as an indicator strain. In addition, cephamycin C and four of its biosynthetic pathway intermediates were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described elsewhere (17). Under these conditions, the retention times for these compounds were as follows: deacetylcephalosporin C, 4 min; cephamycin C, 4.5 min; deacetoxycephalosporin C, 10 min; 7-hydroxycephalosporin C, 14 min; and 7-methoxycephalosporin C, 18 min.

Lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase activities.

Lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase activities were assayed in extracts of N. lactamdurans as described previously (7, 8). One unit of lysine-6-aminotransferase or P6C dehydrogenase was defined as the activity that forms 1 nanomol of product (P6C or NADH, respectively) per min.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of proteins was performed as described by Laemmli (16), using a continuous buffer system (50 mM Tris, 150 mM glycine).

The P7 component of the methoxylation system (12) was detected by immunoblotting. After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon; Millipore) in a semidry electroblotting system (LKB), using a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 100 mM glycine, and 20% methanol, at a constant current of 0.8 mA/cm2. Free binding sites in the membranes were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. The membranes were then treated with the corresponding antibodies in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) containing 300 mM NaCl for 3 h at room temperature with shaking. The membranes were washed for 15 min with 1 M NaCl and then treated with a commercial mouse anti-immunoglobulin G–alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Promega) at a concentration of 15 U/ml in the same buffer for 1 h. After another membrane wash with 1 M NaCl for 15 min, the bands were developed with a commercial stabilized substrate solution of alkaline phosphatase (Promega) at room temperature until color appeared.

RNA purification.

N. lactamdurans MA4213 total RNA from different fermentation conditions was isolated by the guanidinium salt protocol (19), with minor modifications. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The pellet was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the cells were disrupted in a cold mortar with alumina. The disrupted cells were transferred to a clean tube and treated with equal volumes of phenol and ITCG solution (2 M guanidinium isothiocyanate, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 50 mM EDTA, 100 mM lauryl sarcosine, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol). After incubation in a water bath at 55°C for 30 min, the samples were extracted repeatedly with 1 volume of phenol-chloroform solution until the aqueous phase was clean. The RNA was precipitated with 0.3 volume of 8 M LiCl solution, and its purity was analyzed by UV spectrophotometry.

Low-resolution S1 nuclease RNA protection assays.

Low-resolution S1 protection assays were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (26), using 250 μg of total RNA and 2 μg of the selected DNA probe for each reaction. Hybridizations between the RNA and DNA probes were performed at 68°C for 15 h, and the RNA-DNA hybrids were treated with S1 nuclease at 37°C for 1 h, using 250 U of the commercial enzyme (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml. After S1 nuclease digestion, the hybrids were precipitated with ethanol, electrophoresed in an agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane. The membranes were hybridized at 68°C with the same digoxigenin labeled-DNA probe used for the protection assay in a buffer containing 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.1% (wt/vol) lauryl-sarcosine, and 0.02% SDS. Positive hybridization bands were visualized with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody and the corresponding commercial detection system for the conjugated enzyme (Boehringer Mannheim).

Coupling to the xylE reporter gene.

To study if expression from latp and pcbABp was regulated by diaminopropane, DNA fragments containing each promoter (11) were coupled in the appropriate orientation to the xylE in the promoter-probe vector pIJ4083 (3).

RESULTS

Diaminopropane and other diamines stimulate cephamycin production.

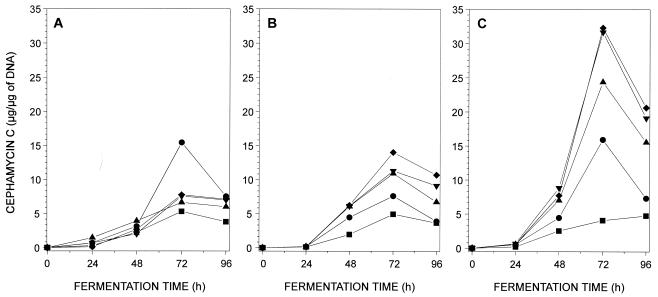

Diaminopropane and to a lesser extent cadaverine and putrescine exerted a strong stimulatory effect (three- to sixfold) on the yield of cephamycin in cultures of N. lactamdurans in NYG medium (Fig. 1). The stimulatory effect of diaminopropane was concentration dependent up to 2.5 g/liter; the optimal concentration of this diamine for cephamycin biosynthesis was about 2.5 g/liter (17 mM), and no further stimulation was observed with a diaminopropane concentration of 5 g/liter (Fig. 1C). Similarly, a clear stimulatory effect was obtained with increasing concentrations of cadaverine (up to 5 g/liter) and putrescine (the best stimulation with putrescine was observed at 0.2 g/liter). These results indicate that the stimulatory effect on cephamycin biosynthesis is exerted by different diamines, but the highest stimulation was obtained with the three-carbon diamine. The diaminopropane stimulatory effect on cephamycin biosynthesis was also observed in Streptomyces clavuligerus, having a maximum stimulatory effect at 5 g of diaminopropane per liter (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Cephamycin C production by N. lactamdurans MA4213 in NYG medium supplemented with putrescine (A), cadaverine (B), and diaminopropane (C). Final diamine concentration in culture medium: 0 (■), 0.2 (●), 1.0 (▴), 2.5 (▾), or 5 (⧫) g/liter.

Diaminopropane does not alter growth or oxygen uptake of N. lactamdurans in batch cultures.

Batch cultures were carried out in a four-twin-vessel fermentor (Biostat Q). Cephamycin production in submerged cultures in the fermentor was higher than in shake flasks. Diaminopropane at 2.5 g/liter increased cephamycin production by about 100% at 90 h but did not alter the oxygen uptake of the N. lactamdurans culture or the growth pattern. The pH profile was similar in control and diaminopropane-supplemented cultures.

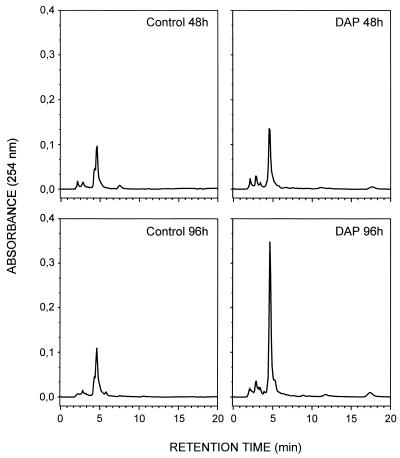

HPLC analysis of cephamycin C and the cephamycin intermediates in samples taken at 48 and 96 h of fermentation showed a large increase in the peak of cephamycin C eluting at 4.5 min in cultures supplemented with diaminopropane (Fig. 2). At 48 h, diaminopropane-supplemented cultures produced 1.2-fold more cephamycin C than unsupplemented cultures; at 96 h, the cephamycin C production was 2.5-fold higher in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures. These results (obtained by comparison of the integrated peak areas) were reproduced in three different experiments. The intermediate deacetylcephalosporin C (with a retention time of 4 min) was detected at low levels in control cultures at 48 and 96 h but was not found in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures, indicating that deacetylcephalosporin C is more efficiently converted to cephamycin C in supplemented cultures.

FIG. 2.

HPLC analysis of antibiotic production by diaminopropane (DAP)-supplemented and unsupplemented cultures of N. lactamdurans MA4213. The cephamycin C peak eluted at a retention time of 4.5 min, and the deacetylcephalosporin C peak eluted at 4 min.

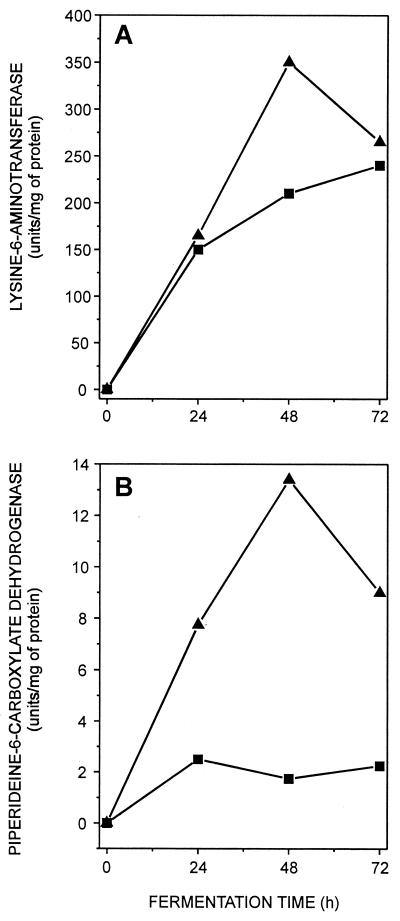

Diaminopropane increases lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase.

The enzyme levels of lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase (the first and second enzymes of the cephamycin pathway) were significantly stimulated in cultures of N. lactamdurans supplemented with diaminopropane. P6C dehydrogenase activity was increased about sixfold in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures at 48 h, and the activity was kept at high levels at 72 h compared to control (unsupplemented) cultures (Fig. 3). The drastic increase in P6C dehydrogenase levels in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures suggests that the dehydrogenation of P6C to give α-aminoadipic acid may be a bottleneck in cephamycin biosynthesis and that stimulation of the P6C dehydrogenase levels may remove one of the bottlenecks of cephamycin biosynthesis.

FIG. 3.

Stimulatory effect of diaminopropane on lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase in N. lactamdurans MA4213. (■) Control (unsupplemented) cultures; (▴) diaminopropane (2.5 g/liter)-supplemented cultures.

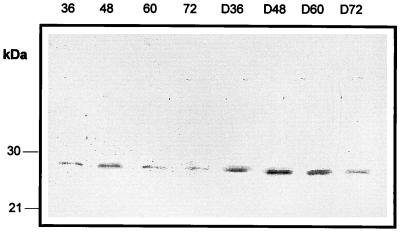

Diaminopropane increases the protein levels of the P7 component of the cephamycin methoxylation system.

The availability of antibodies against the P7 component of the cephamycin methoxylation system provided a useful tool for determining whether the stimulatory effect of diaminopropane on cephamycin biosynthesis was exerted on the synthesis of these proteins or whether it is simply due to stimulation of the activity of some of the biosynthetic enzymes.

Results of the immunoblotting (Fig. 4) showed that the level of the P7 protein at 36, 48, 60, and 72 h was significantly higher in diaminopropane-supplemented cultures than in control cultures.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblotting detection of the P7 protein in control and diaminopropane-supplemented N. lactamdurans MA4213 cultures. Numbers above the lanes indicate culture times (hours). Lanes D36 to D72 represent samples from diaminopropane-supplemented cultures taken at 36 to 72 h.

The diaminopropane effect is exerted at the transcriptional level.

The stimulation of the P7 protein of the methoxylation system and the increased levels of lysine-6-aminotransferase were consistent with the fact that these proteins are synthesized from long polycistronic mRNAs that include the lysine-6-aminotransferase, ACV synthetase, isopenicillin N synthase, methylcephem-3′ hydroxylase, the P7 and P8 proteins (methoxylation system), and the 7′-cephem carbamoyltransferase (11). The pcd gene (encoding P6C dehydrogenase), recently cloned from S. clavuligerus (25), has not been located in the N. lactamdurans genome.

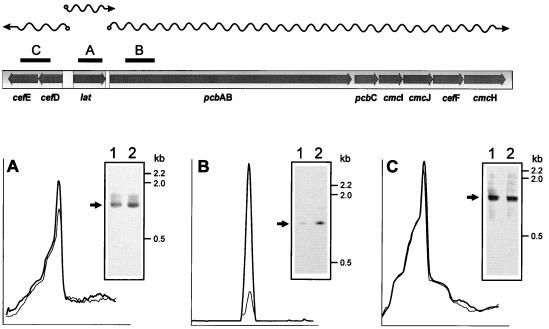

As shown in Fig. 5A, S1 nuclease protection studies indicated that the same fragment of the polycistronic transcript was protected with a 1,010-bp probe (internal to lat) in control and diaminopropane-supplemented cultures, but the intensity of the hybridization was 21% higher in RNA preparations from diaminopropane-supplemented cultures. A high stimulation by diaminopropane (79%) was also observed when a 1,083-bp probe corresponding to the 5′ end of the pcbAB gene was used as the probe in S1 protection experiments (Fig. 5B). This result suggests that expression of the long transcript corresponding to pcbAB and the late genes (11) is particularly enhanced by diaminopropane. However, the band corresponding to the transcript of the cefD and cefE genes (protected by the 1,392-bp probe) showed no difference in intensity, suggesting that expression from the cefD promoter is not stimulated by diaminopropane.

FIG. 5.

Low-resolution S1 protection study of selected regions of the cephamycin C cluster from N. lactamdurans, in diaminopropane-supplemented (lanes 2) and unsupplemented (lanes 1) cultures. Total RNA was extracted from cells harvested at 48 h and hybridized with the following probes: (A) SalI-NotI fragment (1,010 bp), internal to the lat gene; (B) PstI fragment (1,083 bp), corresponding to the initial region of the pcbAB gene; (C) XmnI-BamHI fragment (1,392 bp), covering part of cefD and cefE genes. A map of the cephamycin biosynthetic genes and the corresponding transcriptional units is shown at the top. The protected bands are indicated by arrows. The results are very similar in repeated experiments with an approximate 5% error in band intensity, using always the same RNA/probe DNA ratio.

Diaminopropane stimulates transcription initiation at the lat and pcbAB promoters.

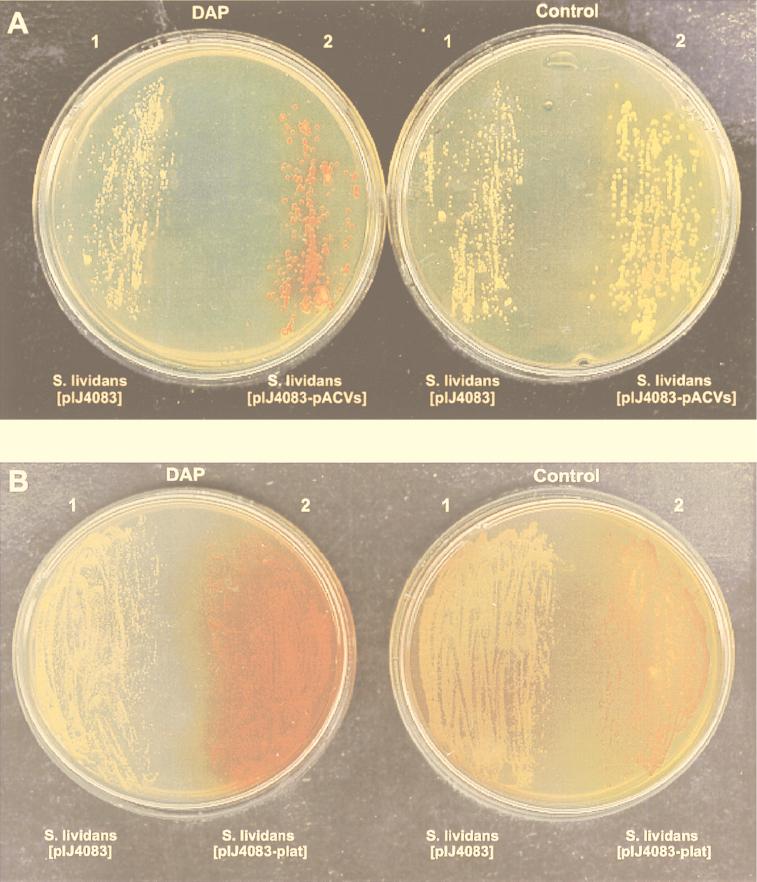

To confirm that the diaminopropane effect on transcription of the polycistronic mRNAs corresponding to lat, pcbAB, and the late genes of the pathway was exerted at the transcriptional level, the two known promoters of this region (latp and pcbABp) were coupled to the xylE reporter gene. As shown in Fig. 6, a moderate catechol oxygenase activity (yellow color) was observed in S. lividans transformants with the xylE gene under either the lat or pcbAB promoter. No formation of pigment was observed in S. lividans cultures transformed with the control plasmid (pIJ4083) without insert.

FIG. 6.

Effect of diaminopropane on xylE gene (encoding catechol oxygenase) from promoters pcbABp (A) and latp (B) of the N. lactamdurans cephamycin C cluster. S. lividans containing the indicated plasmids was grown on Trypticase soy agar plates with 25 μg of thiostrepton per ml for 36 h, and the plates were sprayed with 1 M catechol solution for color developing. Right, control (unsupplemented) plates; left, diaminopropane (DAP) (2.5 g/liter)-supplemented plates. pcbABp is indicated as pACVs.

The pigment formed by the catechol oxygenase increased considerably (to a reddish color) in plates supplemented with diaminopropane (5 g/liter). The color formed in S. lividans transformed with pIJ4083 under pcbABp was particularly strong after only 30 min of incubation, whereas expression from latp required a longer incubation time (24 h) to obtain the same color. Although no precise quantification of reporter gene activity is possible in solid medium, the increase in catechol oxygenase activity with respect to the promoterless pIJ4083 constructions is at least twofold, in good correlation with the stimulation observed in RNA studies.

DISCUSSION

Although the importance of diamines in biological systems is well documented (9, 15), very little is known about their mechanism of action, particularly with respect to the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In E. coli, putrescine, cadaverine, and spermidine are formed through the action of basic amino acid decarboxylases (30). Recently Sekowska et al. (28) reported that in Bacillus subtilis there is a single pathway to polyamines starting from arginine with agmatine as an intermediate. However, it is unknown whether a similar biosynthetic pathway occurs in Nocardia and other gram-positive bacteria.

Polyamines are used as nitrogen (and carbon) sources by different microorganisms. In S. lividans, lysine is known to be decarboxylated to cadaverine that is later further oxidized to 2-ketoglutarate (21). However, in the β-lactam producers N. lactamdurans and S. clavuligerus, lysine is not significantly degraded to cadaverine (10) but instead is converted to α-aminoadipic acid by the lysine-6-aminotransferase (20).

In the present work, we report that the biosynthesis of cephamycin C was stimulated by several diamines, in a mechanism that involves a positive effect on the levels of some biosynthetic enzymes, including lysine-6-aminotransferase and P6C dehydrogenase and the P7 protein of the methoxylation system. Unfortunately, the gene encoding the N. lactamdurans P6C decarboxylase is not located in the cephamycin cluster and has not been cloned. Therefore, we cannot conclude whether the substantial stimulation of the P6C dehydrogenase by diaminopropane is exerted at the transcriptional level. Our results clearly indicate that diaminopropane acts by inducing expression of the mRNAs for cephamycin biosynthesis at the pcbAB promoter and to a lesser extent at the lat promoter. These two promoters are used for expressing the early (lat, pcbAB, and pcbC) and late (cefF, cmcH, cmcI, and cmcJ) genes of the cephamycin pathway (11). Interestingly, no significant stimulation of the expression from the cefDE promoter (which is located in opposite orientation to the lat and pcbAB promoters) was observed.

The stimulatory effect could be due to a stabilization of mRNA. However, the finding that diaminopropane also stimulates expression from the lat and pcbAB promoters when coupled to the xylE reporter gene strongly supports an inducing effect on gene expression.

To some extent, the enhancing effect of diaminopropane on transcription is promoter specific. The strong induction of pcbABp by diaminopropane makes this promoter useful for inducible expression at will of genes in N. lactamdurans, in S. lividans, and probably in other actinomycetes.

Induction by the diamines following their accumulation may be a metabolic signal to trigger antibiotic production. Intracellular accumulation of diamines may regulate the lysine catabolic pathway, therefore affecting the lysine supply for cephamycin biosynthesis. However, it is unclear whether there is a diamine biosynthetic pathway in N. lactamdurans. Alternatively, the presence of extracellular diamines may indicate that diamine-producing bacteria are growing and competing for nutrients in the Nocardia habitat, signaling that cephamycin biosynthesis must be triggered as a defense mechanism.

Addition of diamines at high concentration may provoke a stress response resulting in up-regulation of stress-controlled promoters through ςS. However, no evidence for or against this hypothesis is available at this time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by grants BIO97-0289-CO2 from the CICYT and by a Generic Project of the Agencia de Desarrollo of Castilla and León (10-2/98/LE/0003). A. L. Leitão was supported by a PRAXIS XXI fellowship (BD13931/97) (Portugal), and F. J. Enguita received a fellowship from the PFPI Program, Ministry of Education and Culture (Spain).

We thank M. Corrales, M. Mediavilla, and R. Barrientos for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aharonowitz Y, Cohen G, Martín J F. Penicillin and cephalosporin biosynthetic genes: structure, organization, regulation and evolution. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:461–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton K. A study of the conditions and mechanism of the diphenylamine reaction for the colorimetric estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J. 1956;62:315–323. doi: 10.1042/bj0620315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton T M, Bibb M J. Streptomyces promoter-probe plasmids that utilize the xylE gene of Pseudomonas putida. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1077. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coque J J R, de la Fuente J L, Liras P, Martín J F. Overexpression of the Nocardia lactamdurans α-aminoadipyl-cysteinyl-valine synthetase in Streptomyces lividans. The purified multienzyme uses cystathionine and 6-oxopiperidine 2-carboxylate as substrates for synthesis of the tripeptide. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0264r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coque J J R, Liras P, Láiz L, Martín J F. A gene encoding lysine 6-aminotransferase, which forms the β-lactam precursor α-aminoadipic acid, is located in the cluster of cephamycin biosynthetic genes in Nocardia lactamdurans. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6258–6264. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6258-6264.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coque J J R, Liras P, Martín J F. Genes for a β-lactamase, a penicillin-binding protein and a transmembrane protein are clustered with the cephamycin biosynthetic genes in Nocardia lactamdurans. EMBO J. 1993;12:631–639. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coque J J R, Martín J F, Calzada J G, Liras P. The cephamycin biosynthetic genes pcbAB, encoding a large multidomain peptide synthetase, and pcbC of Nocardia lactamdurans are clustered together in an organization different from Acremonium chrysogenum and Penicillium chrysogenum. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De la Fuente J L, Rumbero A, Martín J F, Liras P. Δ-1-Piperideine-6-carboxylate dehydrogenase, a new enzyme that forms α-aminoadipate in Streptomyces clavuligerus and other cephamycin C-producing actinomycetes. Biochem J. 1997;327:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De la Vega A L, Delcour A H. Polyamines decrease Escherichia coli outer membrane permeability. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3715–3721. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3715-3721.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domínguez, H., and J. F. Martín. Unpublished results.

- 11.Enguita F J, Coque J J R, Liras P, Martín J F. The nine genes of the Nocardia lactamdurans cephamycin cluster are transcribed into large mRNAs from three promoters, two of them located in a bidirectional promoter region. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5489–5494. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5489-5494.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enguita F J, Liras P, Leitão A L, Martín J F. Interaction of the two proteins of the methoxylation system involved in cephamycin C biosynthesis. Immunoaffinity, protein cross-linking, and fluorescence spectroscopy studies. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33225–33230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginther C L. Sporulation and serine protease production by Streptomyces lactamdurans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;15:522–526. doi: 10.1128/aac.15.4.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inamine, E., and J. Birnbaum. August 1976. U.S. patent 3,977,942.

- 15.Koshi P, Vaara M. Polyamines as constituents of the outer membranes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella tryphimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3695–3699. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3695-3699.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leitão A L, Enguita F J, Martín J F. Improved oxygen transfer in cultures of Nocardia lactamdurans maintains the cephamycin biosynthetic proteins for prolonged times and enhances the conversion of deacetylcephalosporin into cephamycin C. J Biotechnol. 1997;58:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitão A L, Enguita F J, De la Fuente J L, Liras P, Martín J F. Allophane increases the protein levels of several cephamycin biosynthetic enzymes in Nocardia lactamdurans. Microbiology. 1996;142:3399–3406. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald R J, Swift G H, Przybyla A E, Chirgwin J M. Isolation of RNA using guanidinium salts. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madduri K, Shapiro S, DeMarco A C, White R L, Stuttard C, Vining L C. Lysine catabolism and α-aminoadipate synthesis in Streptomyces clavuligerus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:358–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00172726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madduri K, Stuttard C, Vining L C. Lysine catabolism in Streptomyces sp. is primarily through cadaverine: β-lactam producers also make α-aminoadipate. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:299–302. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.299-302.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martín J F. New aspects of genes and enzymes for β-lactam antibiotic biosynthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s002530051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martín J F, Liras P. Organization and expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:173–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsui K, Igarashi K, Kakegawa T, Hirose S. Preferential stimulation of the in vivo synthesis of a protein by polyamines in Escherichia coli: purification and properties of the specific protein. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2679–2683. doi: 10.1021/bi00307a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Llarena F J, Rodríguez-García A, Enguita F J, Martín J F, Liras P. The pcd gene encoding piperideine-6-carboxylate dehydrogenase involved in biosynthesis of α-aminoadipic acid is located in the cephamycin cluster of Streptomyces clavuligerus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4753–4756. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4753-4756.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawada Y, Konomi T, Solomon N A, Demain A L. Increase in activity of β-lactam synthetases after growth of Cephalosporium acremonium with methionine or norleucine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekowska A, Bertin P, Danchin A. Characterization of polyamine synthesis pathway in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:851–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabor C W, Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabor C W, Tabor H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]