Abstract

Patient: Female, 49-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Bifid ureter with blind ending

Symptoms: Lumbar pain • urinary infection

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Urology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

The blind-ending branch of a bifid ureter is a rare congenital anomaly which is usually asymptomatic but can occasionally give rise to various symptoms, such as chronic abdominal pain. Diagnosis is most often confirmed radiologically, and treatment is usually conservative. Surgical resection of the blind ending of a bifid ureter should be considered in cases of persistent symptoms.

Case Report:

A female patient of 49 years of age presented with intermittent right lumbar pain, repetitive urinary infections and microscopic hematuria.

We present here the diagnostic work-up of the case, leading to the identification of the existence of ureteral bifidity located at the lower third of the ureter and of a blind ending of the bifid ureter. Several regimens of various antibiotics failed to resolve the symptoms. It was decided to carry out a laparoscopic resection of the blind ending of the bifid ureter. We describe the practical procedures of the surgical operation and discuss briefly the embryological etiology and the physiopathology of the condition as well as the principal diagnostic modalities. Since the surgery, the patient has been symptom-free.

Conclusions:

Despite being usually asymptomatic, the rare congenital anomaly of a bifid ureter with a blind ending can occasionally give rise to symptoms such as recurrent infections and persistent abdominal pain. Laparoscopic-based resection of the blind ending should be considered in such cases.

Keywords: Abdominal Pain; Hand-Assisted Laparoscopy; Ureter; Ureter, Bifid or Double

Background

The blind-ending branch of a bifid ureter is a rare congenital anomaly [1]. The literature has reported approximately 200 cases [2]. Since most patients are asymptomatic, the condition is frequently overlooked. In some cases, however, the anatomic variant can give rise to several symptoms, such as abdominal pain. Diagnosis is most often established as the result of radiological examination, and treatment is usually conservative. Although rare, it is important to be aware of the condition, particularly if unrelated abdominal interventions may be being planned.

We present here the case of a woman with a blind-ending branch of a bifid ureter with recurring clinical symptoms. In our case, we successfully used laparoscopic surgery to remove the blind-ending bifid ureter.

Case Report

A female patient of 49 years of age (body weight 60 kg; height 162.5 cm; body mass index 22.9 kg/m2) and with no relevant comorbidities presented with intermittent right lumbar pain, repetitive urinary infections, and microscopic hematuria. She reported a previous diagnosis of “probable ureteral malformation” for which no formal supporting documentation or data could be located. An initial clinical examination revealed no particular abnormal findings. Biological tests conducted on the day of presentation showed a normal renal function (creatinine: 0.8 mg/dL) and the absence of any inflammatory conditions (C-reactive protein: 1 mg/L). Analysis of the urine revealed microscopic hematuria without pyuria. Flexible cystoscopy was conducted and showed a normal bladder with 2 normally implanted ureteral orifices.

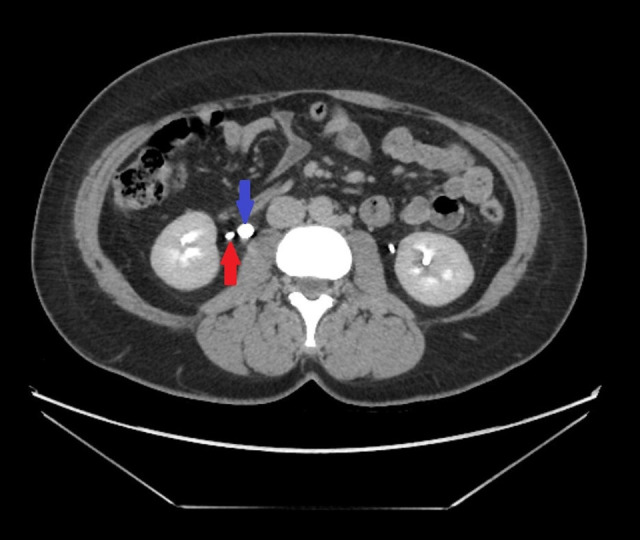

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed the right ureter to be composed of first branch that had a classical normal renal implantation and a second ureter that had a blind ending (Figures 1, 2). A voiding cystogram was conducted and had normal results, thus ruling out the possibility of ureteral reflux.

Figure 1.

Transversal abdominal computed tomography image acquired 10 min after administration of contrast media showing a right bifid ureter with a branch that has a blind ending (blue arrow) and a single pyelocaliciel system (red arrow).

Figure 2.

3D reconstruction of the urinary system. The right bifid ureter with blind ending can be clearly seen.

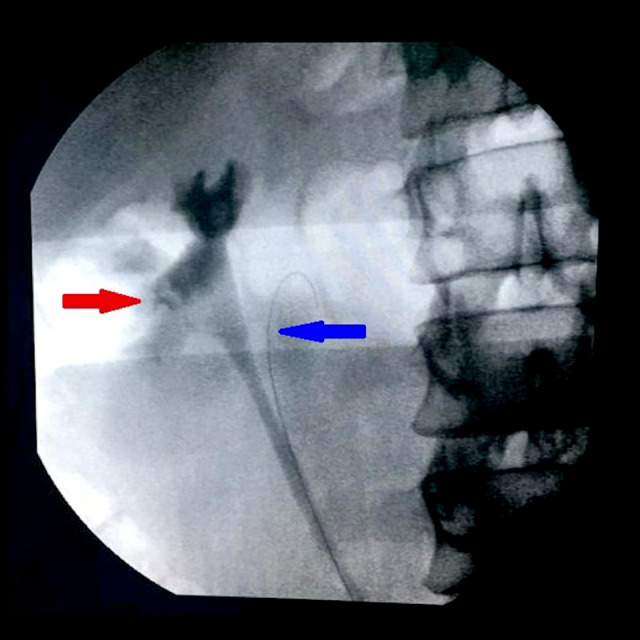

The next step in our investigation was achieving a diagnostic rigid ureteroscopy, which confirmed the existence of ureteral bifidity located at the lower third of the ureter. A retrograde pyelography procedure was then performed and confirmed the presence of a first ureteral branch with normal renal implantation and a second ureteral branch whose proximal extremity was blind ending (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Retrograde uterero pyelograph confirming the single pyelocaliciel system (red arrow). The ureteral catheter is placed in the blind ending (blue arrow).

Further investigation was carried out by ureteroscopy, which once more confirmed the existence of the blind ending and the absence of any communication with the pyelocaliceal system. In this ureteroscopy examination, no suspicious lesions were observed in the blind ending branch.

Despite several correctly complied regimens of antibiotic treatment, urinary infections continually recurred, and the patient reported persistent abdominal pain. Therefore, it was decided to propose to the patient that the blind ending of the bifid ureter be resected by a laparoscopic surgery procedure. The patient gave informed consent.

Surgical Procedure

Prior to the laparoscopic intervention, prophylactic antibiotics were administered (ciprofloxacin 500 mg, 1 injection). For the surgery, the patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position with appropriate cushioning and support.

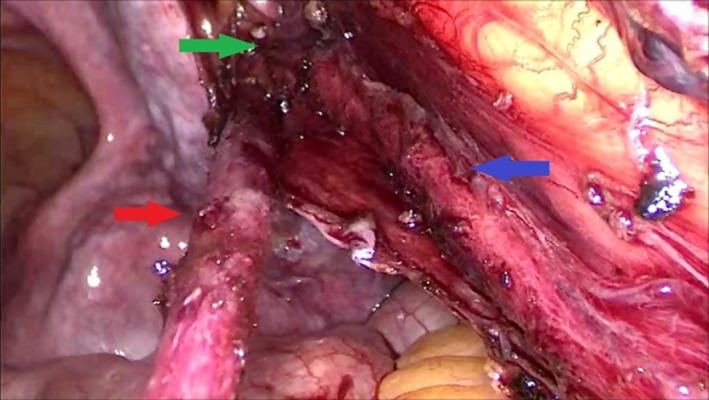

The procedure began with the endoscopic placement of a double J catheter in the healthy ureter and a ureteral catheter in the blind-ending ureter. These were placed to facilitate the identification of the ureters during the laparoscopic procedure. The ureteral catheter allowed identification of the blind-ending branch and was withdrawn before resection. A bladder catheter was placed after the endoscopic procedure. An initial trocar for laparoscopy was inserted at the lateral of the right rectus muscle, at the level of the umbilicus. A total of 3 working trocars were inserted. One of these (5 mm) was placed on the right iliac fossa and another (5 mm) on the right hypochondrium. The third trocar (11 mm) was placed on the patient’s right flank. The line of Toldt was incised to mobilize the ascending colon medially. The 2 ureters could be easily identified, due to the presence of the catheters. Likewise, the proximal extremity of the blind-ending ureter was easily identified and was released from the proximal extremity up to its insertion in the healthy ureter. At this stage, the catheter that had been inserted to facilitate the identification of the ureter was removed. The blind-ending ureter was clipped at the point of its insertion into the healthy ureter and was resected between 2 clips (Figure 4). The resected blind-ending ureter was then removed from the abdomen via the 11 mm trocar. Finally, a drain was placed over the site of the laparoscopic intervention. A prophylactic course of anti-thrombotic treatment was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin 4000 UI/0.4 mL once a day for 10 days).

Figure 4.

Resection of the blind-ending ureter (red arrow) up to the point of its insertion (green arrow) into the healthy ureter (blue arrow).

On the first day after surgery, the venous catheter, the bladder catheter, and the drain were all removed. The patient was discharged on the second day after surgery.

The patient was examined 3 weeks after the surgery, and the double J catheter from the healthy ureter was removed. Three weeks after this, an ultrasound examination was conducted, which confirmed that there was no ureterohydronephrosis. The patient reported the absence of abdominal pain and has not since re-presented for urinary infections.

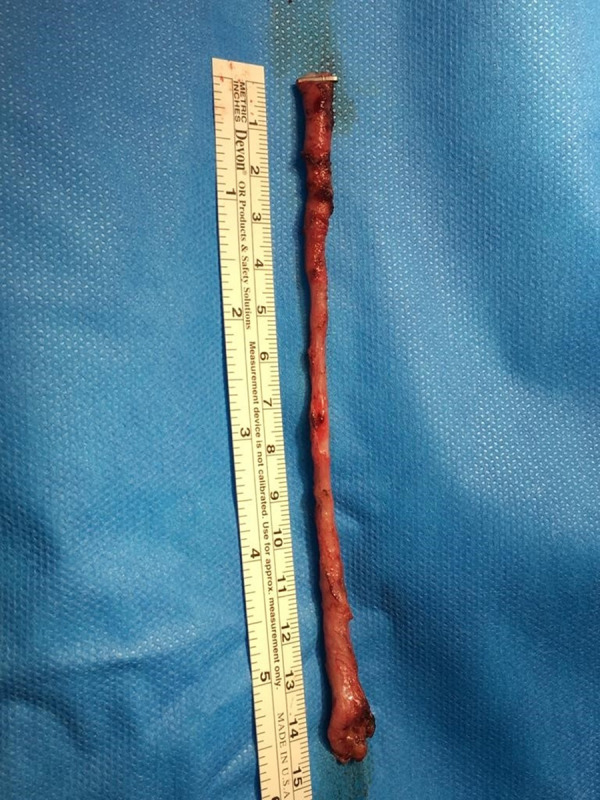

Histopathological analysis of the ureteral segment that had been removed (Figure 5) showed some isolated abnormalities of the urothelial coating and occasional thickening of the muscle wall. There was no sign of any malignancy.

Figure 5.

The surgically removed blind-ending bifid ureter.

Discussion

Embryology

At the 28th day of gestation, the ureteral bud – the precursor of the urine collection system – separates from the Wolffian or mesonephric duct and forms the metanephric mesenchyme, or future nephron. Several anomalies can occur at this stage of embryogenesis giving rise to several urological malformations. A bifid ureter is a result of an early division of the ureteral bud, which in most cases gives rise to the formation of 2 pyelo-caliciel systems that combine and flow into the bladder in a single ureterovesical orifice [1]. The uretero-ureteral junction occurs at various levels: pyelic, lumbar, iliac, pelvic, or intramural. In cases of bifid ureters with a blind-ending branch, the latter detaches itself from the distal or middle portion of the orthotopic ureter [3]. In the case of a bifid ureter with a blind-ending, the normal development of 1 of the 2 ureters, resulting from the division of the ureteral bud, is halted so the ureter does not reach the future kidney. There is therefore only a single pyelocaliceal system, in contrast to a complete bifid ureter where there are 2. Ureteral duplication is the result of 2 ureteral buds whose ureters reach the bladder via 2, quite separate, orifices.

Physiopathology

A bifid ureter with a blind-ending occurs 3 times more often in women than in men and is located mostly on the right side (twice as often than on the left) [4].

Patients with such anomalies are mostly asymptomatic; however, they can also present with abdominal pain, have repeated urinary infections, have hematuria, or be more prone to the formation of stones [5,6].

So-called “yo-yo uretero-ureteral reflux” occurs when there is a lack of peristaltic synchrony between the 2 ureteral branches [7]. Thus, when antegrade urine flow reaches the junction of the healthy ureter and the blind-ending ureter, a retrograde flow is channeled toward the blind-ending branch because of the greater pressure in the distal section, namely the lower branch of the Y, corresponding to the junction of the 2 ureters, than in the blind-ending branch [1].

It is this reflux phenomenon which explains the chronic inflammation in the blind-ending ureteral branch and the resulting abdominal pain. The reflux is also responsible for the fact that the blind-ending ureter is only partially emptied, therefore giving rise to stagnation of the urine in the blind-end and a greater propensity for urinary infection and stone formation. Rare cases of urothelial carcinoma have been reported in the blind endings of bifid ureters [8,9].

Diagnostic Methods

In the past, the method of choice for the diagnosis of blind-ending bifid ureteral anomalies was intravenous urography, but this has now been largely replaced by CT scans [2], which can yield reconstructed 3D images providing greater overall perspective and diagnostic precision. However, it can still happen that the identification of blind-ending ureters is missed on radiological examination, even when a contrast medium is used. For example, if there is edema at the level of the ureteroureteral junction, or if there is compression or abnormal peristalsis in the blind-ending, then the latter may not show any contrast-enhanced attenuation/opacity [2]. Likewise, if the CT images are acquired too soon, when the iodinated contrast has not yet opacified the ureter, the blind ending can be missed.

A possible alternative imaging modality to CT is magnetic resonance imaging, which should be used if the patient is allergic to the iodine-based contrast agent used in CT. Retrograde pyelography and diagnostic ureteroscopy can also provide useful diagnostic information [4].

Treatment

If the diagnosis of a blind-ending bifid ureter is established as the result of an incidental finding, for example, at a radiological examination of a patient with no clinical symptoms of possible abnormalities in the ureters, the management approach should be conservative and no therapeutic treatment initiated. In cases where there is stone formation in the blind-ending branch, therapeutic ureteroscopy can be considered [5]. Urinary infections should first be treated with appropriate antibiotics, according to the particular antimicrobial susceptibility. In cases of unsuccessful antibiotic treatment or repeated infections, surgical intervention should be considered, such as transperitoneal or retroperitoneal laparoscopic resection of the blind-ending ureteral branch.

In the few cases of bifid blind-ending ureters that have been reported, open surgical resection has traditionally been carried out on symptomatic patients. A first description of a laparoscopic retroperitoneal resection of a blind-ending bifid ureter was reported in 2005 [10]. The comparative benefits and disadvantages of open versus laparoscopic surgery (and more recently robotic surgery) have been established and validated in many pathologies [11,12].

The low incidence of cases precludes the possibility of carrying out widespread, statistically valid trials to determine the pros and cons of the various surgical approaches for blind-ending bifid ureters.

The choice of laparoscopic surgery in our particular case of bifid blind-ending ureter was motivated by our experience in laparoscopic procedures in other pathologies, with the main rationale being a decrease in the level of the patient’s postoperative pain, length of hospitalization, and overall length of convalescence. The successful outcome of our patient seems to justify our choice of surgical approach.

Conclusions

A bifid ureter with a blind ending is a rare anatomic anomaly, which is mostly asymptomatic. In cases of repeated clinical symptoms, it is all the more necessary to establish an accurate and reliable diagnosis. If drug treatment is unsuccessful, surgical intervention should be considered. Laparoscopic resection of the blind-ending ureter is effective and easy to conduct.

Footnotes

Department and Institution in Which Work Was Done

Department of Urology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Ardenne Libramont, Libramont, Belgium.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Moghul S, Liyanage S, Vijayananda S, et al. Bifid ureter with blind-ending branch: A rare anatomic variant detected during antegrade ureteric stent insertion. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13:1199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang E, Santillan C, O’Boyle MK. Blind-ending branch of a bifid ureter: Multidetector CT imaging findings. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:38–40. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muraro GB, Pecori M, Giusti G, Masini GC. Blind-ending branch of bifid ureter: Report of seven cases. Urol Radiol. 1985;7:12–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02926840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karabacak OR, Bozkurt H, Dilli A, et al. Distal blind-ending branch of a bifid ureter. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9(1):188–90. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.30951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halim HA, Al-Awadi KA, Kehinde E, Mahmoud AH. Blind-ending ureteral duplication with calculi. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:346–48. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salakos C, Tyritzis SI, Papanastasiou D, et al. Double-blind ureteral duplication: A rare urologic anomaly. Urology. 2009;73:210.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan N, Elkin M. Bifid renal pelvis and ureters. Radiographic and cinefluorographic observations. Br J Urol. 1968;40:235–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1968.tb09879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura H, Sasaki N. Transitional cell carcinoma in the blind-ending branch of the bifid ureter. Br J Urol. 1998;82:307–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodama K, Iwasa Y, Motoi I, et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with a blind-ending bifid ureter. Int Canc Conf J. 2012;1:147–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlmutter AE, Parousis VX, Farivar-Mohseni H. Laparoscopic retroperito-neal resection of blind-ending bifid ureter in patient with recurrent urinary tract infections. Urology. 2005;65(2):388. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hideaki M, Gaku K, Akinobu G, et al. Comparison of surgical stress between laparoscopy and open surgery in the field of urology by measurement of humoral mediators. Int J Urol. 2002;9:329–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill IS, Clayman RV, McDougall EM. Advances in urological laparoscopy. J Urol. 1995;154(4):1275–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]