Abstract

Gene III (gIII) of φLf, a filamentous phage specifically infecting Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, was previously shown to encode a virion-associated protein (pIII) required for phage adsorption. In this study, the transcription start site for the gene and the N-terminal sequence of the protein were determined, resulting in the revision of the translation initiation site from the one previously predicted for this gene. For comparative study, the gIII of φXv, a filamentous phage specifically infecting X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, was cloned and sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequences of these two pIIIs exhibit a high degree of identity in their C-terminal halves and possess the structural features typical of the adsorption proteins of filamentous phages: a signal sequence in the N terminus, a long glycine-rich region near the center, and a hydrophobic membrane anchorage domain in the C terminus. The regions between gIII and the upstream gVIII, 128 nucleotides in both phages, are larger than those of other filamentous phages. A hybrid phage of φXv, consisting of the φLf pIII and all the other components derived from φXv, was able to infect X. campestris pv. campestris but not X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, indicating that gIII is the gene specifying host specificity and demonstrating the interchangeability of the pIIIs.

φLf is a filamentous phage (39) specifically infecting Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, a gram-negative pathogen causing black rot in cruciferous plants. It is similar to other filamentous phages in morphology, having a single-stranded circular DNA genome (6,008 nucleotides [nt]), producing RF (replicative form) during DNA replication and propagating without lysis of the host (26, 43). However, several interesting properties different from those of other filamentous phages have been found. First, it has a mechanism to integrate its RF DNA into the host chromosome (11, 15). Second, its origin of viral strand replication is contained within the gene coding for the replication initiation protein (pII) instead of the major intergenic region (IR) as is the case in other filamentous phages (16). Third, its pII possesses sequence domains conserved in the superfamily I Rep proteins of the rolling-circle-replicating replicons, a superfamily not including the proteins of other filamentous phages (19). So far, 10 genes have been assigned to the φLf viral strand. These genes, in the order gII-gX-gV-gVII-gIX-gVIII-gIII-gVI-gI-gXI, organized similarly to those of the Escherichia coli filamentous phages Ff, IKe, and 12-2 (26, 30), were predicted to code for proteins pII, pX, pV, pVII, pIX, pVIII, pIII, pVI, pI, and pXI, respectively. pII, pX, and pV are required for DNA replication (19, 44); pVII and pIX are thought to form the protein coat in conjunction with pVIII, pIII, and pVI (20, 21, 44); pI and pXI are presumably involved in phage morphogenesis (6).

We have previously isolated filamentous phage φXv from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (18). Comparative study of φLf and φXv revealed that (i) they are strictly host specific, each phage being able to infect only its own host, not other X. campestris pathovars; (ii) most regions of their DNA exhibit sequence identity, as demonstrated by Southern hybridization; (iii) each of their antisera can cross-react with the other phage particles, indicating that these phages are closely related, and (iv) when RF DNA or single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) from these phages was electroporated into the nonhost Xanthomonas cells, authentic phage particles were produced, indicating that host specificity is eliminated by skipping the early steps of infection (18). Furthermore, we have shown that when φXv is propagated in the presence of cloned φLf gIII, coding for the adsorption protein, the progeny phage particles produced are able to infect both X. campestris pv. campestris and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (20).

In this study, we revised the φLf gIII coding region from the one assigned previously (45), sequenced the gIII gene of φXv, and demonstrated the interchangeability of gIII between φLf and φXv.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phages, bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Filamentous phages φLf and φXv have been described previously (18, 39). P20H was a nonmucoid mutant isolated from X. campestris pv. campestris strain 11 by nitrous acid mutagenesis (46). X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 36 (Xv36), the pathogen causing spot disease in pepper and tomato, was a gift from S.-T. Hsu, National Chung Hsing University (18). E. coli DH5α (32) was the host for gene cloning. pRKG3 was a plasmid carrying the φLf gIII cloned into the multiple cloning sites of the broad-host-range vector pRK415 (20). LB broth and LB agar (25) were used for growing E. coli (37°C) and X. campestris (28°C) strains. Antibiotics used were ampicillin (50 μg/ml), gentamicin (15 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and tetracycline (15 μg/ml).

Phage techniques.

To propagate the phages, overnight cultures of the host cells, P20H for φLf and Xv36 for φXv, were diluted 20-fold into 125-ml flasks containing 20 ml of LB medium. When the cultures reached 0.5 U of optical density at 550 nm (OD550), the phages were added at a multiplicity of infection of 20 and further grown until stationary phase (ca. 12 h postinfection). Crude phage suspensions were prepared by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 15 min) of the cultures to remove the cells and passing the supernatants through a membrane filter (0.45-μm pore size). Phages were purified by banding in ultracentrifugation as described previously (20). To determine the phage titer, a double-layer bioassay (9) was performed on an LB agar plate. Susceptibility to phage was assayed by a spot test done by dropping 5 μl of a phage-containing suspension onto the freshly poured top agar (0.7%) containing the cells to be tested. Transduction was performed by mixing the appropriately diluted crude phage suspension with the cells to be tested, incubating the mixture for 20 min, and then spreading aliquots of the mixture on LB agar containing antibiotics.

DNA techniques.

Restriction endonucleases, Klenow enzyme, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and other enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. RNase-free DNase and S1 nuclease were obtained from Promega. T4 DNA ligase and SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase were purchased from Gibco Bethesda Research Laboratories, Inc. All enzymes were used as instructed by the suppliers. [γ-32P]ATP and Hybond-N membrane were products of Amersham Life Science. Plasmid extraction, preparation of φLf RF DNA, gene cloning, Southern hybridization, and transformation of E. coli were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (32). Strains of X. campestris were transformed by electroporation (41). Single-stranded DNA sequencing was accomplished by the dideoxy-chain termination method (33) with a Sequenase 2.0 sequencing kit (United States Biochemical Corp.).

Construction of φXv gIII-defective mutant φXvSG.

The φXv mutant defective in gIII, designated φXvSG, was constructed by replacing the 578-bp SphI-SacI fragment internal to the φXv gIII with a gentamicin resistance gene (Gmr cartridge [34]). The RF DNA of φXvSG was maintained as autonomously replicating molecules in P20H. No infective phage particle was produced by P20H(φXvSG).

RNA preparation.

RNA was prepared by the method of Wang and Vodkin (40), with some modifications. An overnight culture of P20H was diluted 20-fold into 30 ml of LB medium. When the cell concentration reached 0.6 U of OD550, φLf was added at a multiplicity of infection of 20 and the culture was grown to an OD550 of 1. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min) and suspended in 0.7 ml of the RNA extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.2] containing 20 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 16 mM dithiothreitol). From this step on, all centrifugations were performed in a Sigma 2K15 centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 10 min. To the cells in the RNA extraction buffer, an equal volume of phenol (pH 4.0 to 4.5) was added, followed by vortexing for 2 min. The aqueous layer was extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform and once with an equal volume of chloroform. After each extraction, the mixture was centrifuged, allowing separation of the aqueous layer from the organic solvents. The RNA was kept overnight at 4°C in the presence of 2 M LiCl and then collected by centrifugation. The pellet was washed twice with cold ethanol (70%) and then dissolved in 50 μl of deionized water which had been treated with 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate. To this RNA solution, 5 μl of RNase-free DNase (50 U) was added. After 30 min at 37°C, the sample was extracted twice with phenol-chloroform, and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol (95%), dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated deionized water, and stored at −70°C until used.

Primer extension.

Primer extension was performed with a 20-residue synthetic oligonucleotide, 5′-GATTTCATACGACACACCGA-3′, complementary to positions 3417 to 3398 (counting from the unique PstI site of the φLf RF DNA) downstream of the gIII start codon. The primer was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP at the 5′ end by using T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified by passage through a Spin column-10 (Sigma). For annealing, the labeled primer (ca. 50,000 cpm) and the RNA (20 to 50 μg) were dissolved in a total volume of 30 μl of annealing buffer (34 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3] containing 50 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM dithiothreitol) and incubated at 80°C for 10 min and then at 48°C for 3 h. The RNA was ethanol precipitated and dissolved in 20 μl of primer extension reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3] containing 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP). After addition of 1 μl of SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (200 U/μl), the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then the reaction mixture was treated with 10 μg of DNase-free RNase. After 30 min at 37°C, the sample was extracted one time each with phenol-chloroform and chloroform and then ethanol precipitated. Pellets were dissolved in 10 μl of 1× DNA sequencing loading buffer (80% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mg of xylene cyanol FF per ml, 1 mg of bromophenol blue per ml) and electrophoresed on DNA sequencing gels. For comparison, the extension products were run next to a sequence ladder generated from the same primer on the φLf ssDNA template.

Protein techniques.

The φXv pIII was purified by gel filtration (Superose 12 column) with a fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system as described for the purification of φLf pIII (20). The pIII protein-containing fraction (a shoulder between peaks 1 and 2) from the first run was passed through the same column and buffer systems, resulting in good separation of the pIII from the other proteins. The eluate in peak 2 containing the φXv pIII was collected. For polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) separation, samples containing the φXv pIII were prepared as described previously (20) and electrophoresed in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (12%) by the method of Laemmli (13). Western blot analysis was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (32), using proteins which had been treated as described by Liu et al. (20). For determination of the N-terminal amino acid sequence, the φLf pIII was separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and then the protein was eluted from the membrane and subjected to Edman degradation in an Applied Biosystems model 476A protein sequencer. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (22).

Sequence analysis.

Signal peptides and membrane anchoring domains were predicted with the PSORT program (27). Multiple sequence alignments were performed with the Lasergene software package from DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the HindIII-HincII fragment containing the φXv gIII has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF069776.

RESULTS

Size of the φLf gIII transcript.

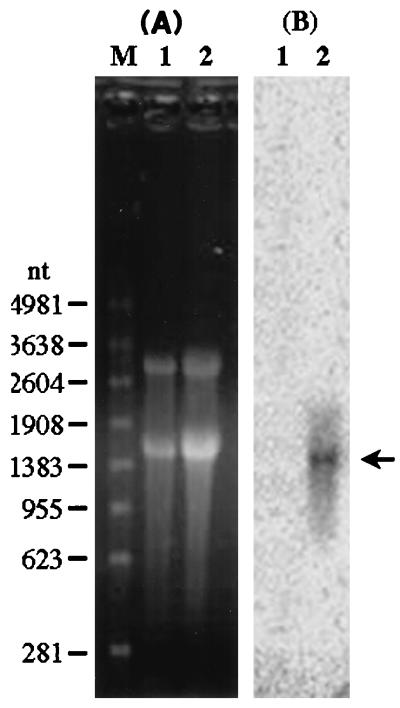

The previously predicted φLf gIII coding region is 1,101 bp in length, lying between gVIII and gVI at nt 3119 to 4222, counting from the unique PstI site of the φLf genome (43, 45). To measure the size of the transcript containing gIII, we carried out Northern blot analysis on the total mRNA extracted from the φLf-infected P20H, using the 731-bp MluI-SacI fragment within gIII as the probe. A transcript of ca. 1.6 kb was detected (Fig. 1). With a size about 400 bp longer than that of gIII, this transcript appears to be a polycistronic mRNA containing an additional gene besides gIII. Since a potential transcription terminator is present in the upstream IR between gVIII and gIII (44), suggesting that gVIII is the last gene of the preceding transcriptional unit, the additional gene is likely to be the 288-bp gVI behind gIII (21).

FIG. 1.

Northern blot analysis of the mRNA extracted from φLf-infected P20H cells, using the 731-bp MluI-SacI fragment within gIII of the φLf RF DNA as the probe. (A) Electrophoresis of the RNA in an agarose gel (1.2%) containing formaldehyde (2%). (B) Autoradiogram of Northern hybridization. Lanes: M, molecular size markers; 1, noninfected P20H; 2, φLf-infected P20H.

Transcription start site of the φLf gIII.

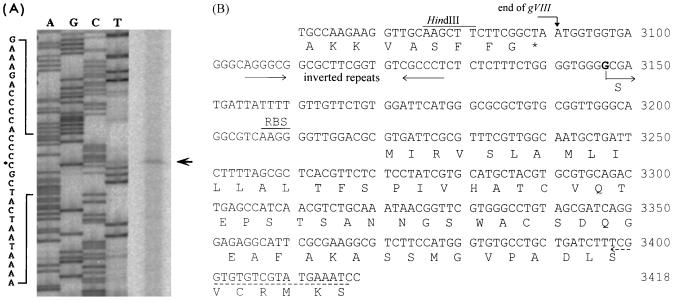

To determine the 5′ end of the 1.6-kb gIII-containing transcript, we performed primer extension using mRNA extracted from the φLf-infected P20H as the template and the 20-mer complementary to nt 3417 to 3398 of the φLf viral strand as the primer. For comparison, a sequencing reaction was performed with the same primer and the φLf ssDNA as the template (Fig. 2A). One primer extension product initiating with a C at nt 3147 was detected (Fig. 2B). It is evident that a 1.6-kb transcript starting here is long enough to contain gIII and gVI and likely extend into gI. In other words, the transcription of this operon is likely terminated within the gI coding region (6). This transcriptional organization is similar to that in Ff phages, where gIII and gVI are organized into a gIII-gVI operon and cotranscribed (26).

FIG. 2.

Determination of the transcription start site for φLf gIII by primer extension, using a 20-mer complementary to nt 3417 to 3398, counting from the unique PstI site of the φLf viral strand DNA. The RNA was prepared from φLf-infected P20H. (A) Gel electrophoresis of the primer extension product (indicated by an arrow). The sequence shown next to the sequencing gel is complementary to that displayed in panel B. The asterisk indicates the base complementary to the 5′ end of the transcript. (B) Nucleotide sequence (nt 3061 to 3418) containing the end of φLf gVIII, the beginning of gIII, and the IR. The upstream putative transcription terminator (inverted repeats) located 93 nt before gIII is indicated by inverted arrows. The dashed arrow indicates the region complementary to the primer used. The transcription start site (boldfaced G) determined here (nt 3147) is indicated by S.

N-terminal sequence of the φLf pIII.

The φLf pIII was purified by FPLC as described previously (20). The purified protein was subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence determination by Edman degradation, which revealed 14 amino acid residues with the sequence TXVQTXPSTSANNG, in which X represents an uncertain residue. This sequence is in good agreement with the previously predicted amino acid sequence of φLf pIII between amino acids (aa) 57 and 70 (45). These data suggest that a 56-residue signal sequence must be cleaved off the predicted nascent protein to produce the mature pIII. This stretch is about twice the length of the signal sequences normally observed (29), indicating that the previously predicted gIII translation initiation site may not be correct.

Revision of the translation initiation site of φLf gIII.

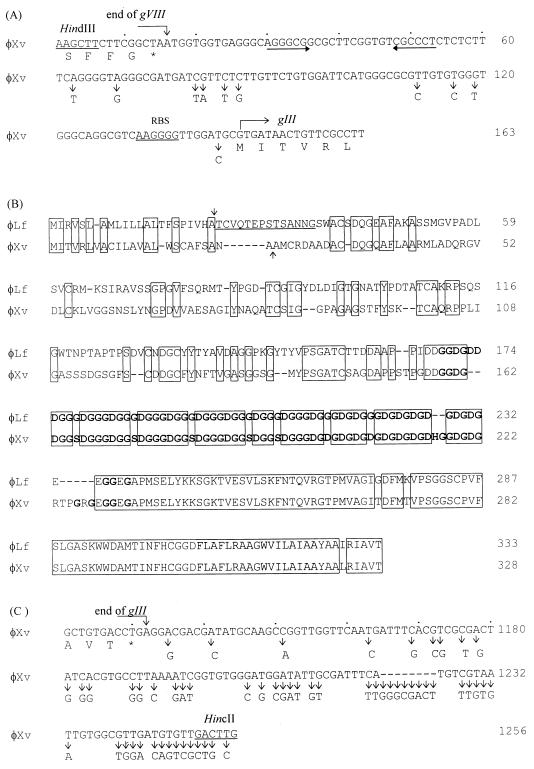

The GTG (nt 3221) specifying methionine (22 residues upstream from the chemically determined N terminus of the mature pIII) is preceded by a possible ribosome-binding site (35), 5′-AAGGgG-3′ (capitalized letters represent nucleotides complementary to the anti-Shine-Dalgarno sequence of the X. campestris pv. campestris 16S rRNA [17]), located 8 nt upstream (Fig. 2B). This GTG, instead of the previously proposed GTG (nt 3119), therefore appears to be the true initiation codon for biosynthesis of the φLf pIII. Translation initiated here would produce a polypeptide of 333 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular weight of 32,857 which has a predicted 22-residue N-terminal signal sequence. After processing, the mature pIII would be 30,497 Da in mass and have an N terminus matching the chemically determined N-terminal sequence (Fig. 3B). This size is a little smaller than that (37 kDa) estimated by SDS-PAGE (20).

FIG. 3.

(A) Upstream flanking sequence of the φXv gIII. The end of gVIII and the beginning of gIII are indicated. The arrows running convergently represent the possible rho-independent transcription termination signal. RBS is the predicted ribosome-binding site. A vertical arrow indicates a base substitution in the corresponding region of the φLf sequence. (B) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of φXv and φLf pIII. Blocked regions possess identical amino acid residues. Gaps were introduced for optimal alignment. Each vertical arrow indicates a possible cleavage site for removal of the N-terminal signal sequence. The 14 residues (underlined) behind the cleavage site of the φLf pIII are the sequence determined chemically. The glycine-rich regions are boldfaced, and the C-terminal hydrophobic regions predicted for membrane anchorage are shadowed. (C) Downstream flanking sequence (124 nt) of the φXv gIII. A vertical arrow indicates a base substitution in the corresponding region of the φLf sequence.

The φLf gVIII coding region has previously been determined (44) and found to terminate at nt 3091 of the φLf genome (Fig. 2B). Thus, revision of the gIII translation initiation site here results in the identification of an IR of 128 nt between gVIII and gIII of the φLf genome.

Sequence of the φXv gIII.

Southern hybridization with the cloned φLf gIII (the insert of pRKG3) as the probe showed a signal for the 1.3-kb HindIII-HincII fragment from the φXv RF DNA. Sequencing of this fragment revealed a total of 1,256 bp (accession no. AF069776). A possible open reading frame (orf328) able to encode 328 residues with a calculated molecular weight of 31,937 was found to initiate with GTG at nt 146 and terminate with TGA at nt 1132. It is preceded by a possible ribosome-binding site (35), 5′-AAGGgG-3′, 8 nt upstream of the predicted initiation codon (Fig. 3A), which is complementary to the anti-Shine-Dalgarno sequence in the X. campestris pv. campestris 16S rRNA (17). The amino acid sequence deduced from orf328 possesses 61.1% identity to that of the φLf pIII, with the highest identity (86%) in the C-terminal 172 residues (Fig. 3B). Structural features typical of filamentous phage pIIIs (4, 8, 10, 12, 37) are present in the φXv pIII: a 24-residue N-terminal signal sequence, a 75-residue glycine-rich region, and a 17-residue C-terminal hydrophobic region (Fig. 3B). After removal of the signal peptide, a mature protein of 29,463 Da would be produced.

The 1,256-bp HindIII-HincII fragment of the φXv DNA has a G+C content of 59.8%, a value which is a little lower than that (63.5%) of the X. campestris chromosome (3). The 145-nt upstream flanking region, starting from the HindIII site, is 93% identical to the corresponding φLf sequence, with only 10 base substitutions (Fig. 3A). This region contains the C-terminal five codons of gVIII (ended at nt 16) and the 128-nt IR between gVIII and gIII. Eleven nucleotides behind gVIII within the IR of the φXv sequence, there is a region (nt 30 to 53) having the potential to form a stem-loop structure which is identical to the putative transcription terminator of φLf in nucleotide sequence and distances from the adjacent genes (nt 3105 to 3128 in Fig. 2B and nt 30 to 53 in Fig. 3A). The downstream flanking sequence of 124 nt shows 63% identity to that of the corresponding region in φLf DNA.

Cross-reactivity of anti-φLf pIII serum with φXv pIII.

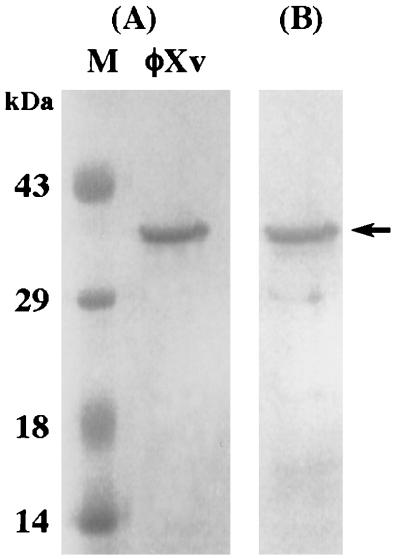

The φXv pIII was purified by two passages through the same gel filtration column (Superose 12) and buffer systems for FPLC as described for the purification of φLf pIII (20). The peak patterns were similar to that observed in the purification of φLf pIII, and the φXv pIII was detected in the second peak from the second column chromatography. In SDS-PAGE, the sample from this fraction formed a major protein band with an apparent mass of 36 kDa, which is a little larger than the value calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence of the mature φXv pIII (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

(A) SDS-PAGE of the φXv pIII purified from phage particles by FPLC. Lane M, protein molecular markers. (B) Western blot analysis of the φXv pIII from panel A with the antibody raised against the purified φLf pIII. The position of the φXv pIII is indicated by an arrow.

Our previous investigation demonstrated that the φLf and φXv phage particles can be cross-inactivated by the antiserum raised against the other phage particle (18). In this study, the pIIIs of φLf and φXv have been shown to possess a high degree of identity in amino acid sequence in their C termini. To test for cross-reactivity, we carried out Western blot analysis of the φXv pIII, using the serum raised against the purified φLf pIII. Strong reactivity was observed between the anti-φLf pIII serum and the purified φXv pIII (Fig. 4B).

Host specificity determinant of X. campestris filamentous phages.

φXvSG was a derivative of φXv with the fragment specifying aa 46 to 237 (Fig. 3B), encoded by the 578-bp SphI-SacI fragment, of gIII replaced by a Gmr cartridge. It was maintained as an autonomously replicating molecule after being electroporated into Xv36 or P20H. No infective phage particle was detectable by transduction in the supernatants of these cultures, indicating a lack of the complete process for normal propagation. However, upon superinfection of Xv36(φXvSG) with the wild-type φXv, phage particles able to transduce Xv36 to gentamicin resistance were detectable in the culture supernatant, indicating that the deficiency in pIII can be complemented by the wild-type φXv gIII.

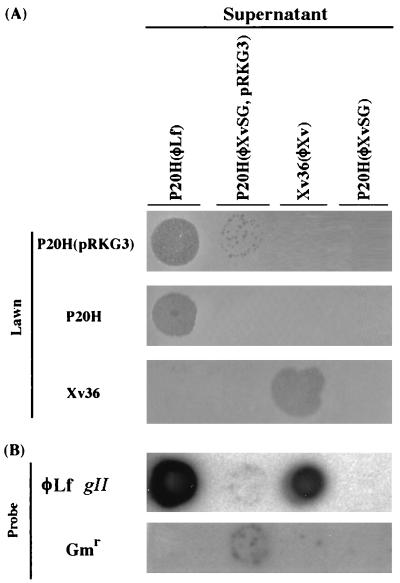

We have previously shown that pRKG3, a plasmid carrying the φLf gIII cloned into the broad-host-range vector pRK415, is able to express the φLf pIII in X. campestris and E. coli (20). In addition, when Xv36(pRKG3) was infected with φXv, the phage particles produced were able to infect Xv36 and P20H. Therefore, it was proposed that a mixture of authentic φXv and hybrid phage particles containing the φLf pIII and all the other components derived from φXv had been produced (20). To test whether the cloned φLf gIII can complement the deficiency in φXv pIII, we electroporated φXvSG into P20H(pRKG3) and assayed the resulting strain, P20H(pRKG3, φXvSG), for the production of phage particles by transduction. P20H(pRKG3, φXvSG) was found to release phage particles into the culture supernatant (about 1.2 × 104 PFU/ml) which were able to transduce P20H and P20H(pRKG3) to gentamicin resistance. In contrast, the same phage particles were not able to transduce Xv36 or Xv36(pRKG3), suggesting that a change of host specificity had resulted from the incorporation of the φLf pIII during the formation of hybrid phage particles. In a spot test, the phage particles released from P20H(pRKG3, φXvSG) were able to form clearing zones on a lawn of P20H(pRKG3) but not on the lawns of Xv36(pRKG3) or Xv36 (Fig. 5A). These results coincide with the data obtained in the transduction assay. Here, no clearing zone was observed in the spotted P20H lawn, because the cells without pRKG3, although able to be transduced, could not produce progeny phages necessary for clearing-zone formation (Fig. 5A). To verify that the phage particles released indeed contained φXvSG, Southern hybridization was performed with the φLf gII fragment (16) or the Gmr cartridge as the probe. Due to the high degree of sequence identity between the φXv and φLf gIIs, the φLf gII probe would react with φLf, φXv, and φXvSG, whereas the Gmr probe would hybridize to φXvSG only. As shown in Fig. 5B, both the Gmr and φLf gII probes hybridized to the spot formed on the lawn of P20H(pRKG3) by the phage particles released from P20H(φXvSG, pRKG3), confirming that the particles indeed contained φXvSG.

FIG. 5.

Detection of hybrid phage released from nonpermissive host cells by spot test and Southern hybridization. (A) Five-microliter aliquots of the culture supernatants of P20H(pRKG3, φXvSG) and P20H(φXvSG) were separately spotted on a lawn of P20H(pRKG3), P20H, or Xv36, using the supernatants of P20H(φLf) and Xv36(φXv) as the controls. (B) The spotted regions on the lawn of P20H(pRKG3) (top row in panel A) were transferred by lifting onto a Hybond-N membrane and hybridized with the φLf gII or Gmr probe. The hybridization signal shown by the Xv36(φXv) supernatant (top row in panel B) was generated by the spotted phage φXv, which hybridized to the φLf gII, instead of progeny produced after spotting.

In summary, the hybrid phage containing the φLf pIII and all the other components derived from φXv was infective to X. campestris pv. campestris, the natural host of φLf, but not X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, the natural host of φXv; therefore, we propose pIII to be the determinant specifying the host specificity of X. campestris filamentous phages.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the size of the φLf gIII transcript was estimated, the transcription start site for synthesizing the transcript was detected, and the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the gene product, pIII, was determined. Based on these data, the φLf gIII coding region was revised from the one predicted previously (45). The results obtained in these experiments were used as references for assigning the coding region of the φXv gIII, which has sequence identity to the φLf gIII. The sizes of the proteins thus deduced for the φLf pIII (333 residues) and φXv pIII (328 residues) are about 100 residues less than the pIIIs of Ff (424 residues), IKe (434 residues), and I2-2 (434 residues). Since the φLf genome, with a size of 6,008 nt (43), is smaller than the 6,407-nt genome of Ff (1), the 6,883-nt genome of IKe (28), and the 6,744-nt genome of I2-2 (36), keeping the size of pIII small should be help to maximize DNA usage in order to accommodate the same number of genes as the E. coli filamentous phages. However, revision of the φLf gIII coding region accomplished in this study has in the meantime resulted in the identification of an IR of 128 nt lying between gVIII and gIII of the φLf genome. An IR of the same size is also present in the corresponding region of the φXv genome, according to the sequence data (nt 17 to 145 in Fig. 3A). These IRs are much longer than those in the analogous regions of phages Ff (59 nt), IKe (67 nt), and I2-2 (66 nt), the ones which are second to their respective major IRs (2, 28, 36). The significance of the presence of an IR as large as 128 nt remains to be investigated, and the possibility that this region can accept an insertion of a foreign DNA fragment will be tested.

Both of the φLf and φXv pIIIs possess domains with structural features typical of the pIIIs of the filamentous phages of E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, i.e., the N-terminal signal sequence, the glycine-rich region, and the C-terminal hydrophobic region for membrane anchorage (4, 8, 10, 12, 37). Interestingly, the signal peptide of the φXv pIII shows a low degree of identity in amino acid sequence to that of the φLf pIII. In contrast, the predicted C-terminal 17-residue membrane anchorage domain (aa 303 to 319) is identical in sequence to that of the φLf pIII, aa 308 to 324 (Fig. 3B). The 75-residue glycine-rich region (aa 159 to 233) of the φXv pIII has sequences mainly appearing as GD, GGSD, and GGGD repeating 11, 5, and 4 times, respectively (Fig. 3B). While a serine residue is absent from the glycine-rich region of the φLf pIII, the glycine residues are clustered mainly as GD and GGGD repeating 9 and 10 times, respectively (Fig. 3B) (45).

In addition to the domain sequence conservation observed in the pIIIs of φLf and φXv, the pIII of φXo, a filamentous phage of X. oryzae pv. oryzae, has been found to possess similar domains (48). Thus, conservation of the domain sequence seems to be one of the common properties of the filamentous phage adsorption proteins. However, an exception seems to exist in Cf, a filamentous phage of X. campestris pv. citri (7), whose pIII has been shown to be interchangeable with the analogous gene of Xf (47), a filamentous phage of X. oryzae pv. oryzae (24). While the Xf gIII sequence was not available, we were able to compare the Cf pIII sequence (23) with those of the φLf and φXv pIIIs. Surprisingly, neither sequence identity nor similarity in domain conservation was found. The lack of domain conservation indicates the Cf pIII to be an exception to the filamentous phage pIIIs.

In phages Ff and IKe, the four minor coat proteins (pIII, pVI, pVII, and pIX) are present at three to five copies each in the phage particle, with pIII and pVI located at one end and pVII and pIX located at the other (26). pIII mediates phage adsorption to pili (receptor recognition) and is necessary for phage uncoating and DNA penetration into the host cell, which also requires the function of the host proteins TolQ, TolR, and TolA (14, 31, 38, 42). The pIIIs of these two phages possess a very low degree of overall similarity (15%), with the highest degree of similarity (43%) being found in the regions required for penetration, and one pIII cannot replace the functionally analogous protein of the other phage (4, 5, 28). In contrast to these cases, we have shown that cloned φLf gIII can complement the deficiency in φXv pIII, indicating that the pIIIs of φLf and φXv are interchangeable. These findings suggest that φLf and φXv share the sequence information required for assembling the pIII into phage particles. The required sequence information in pIII is most likely located in the C-terminal half of the polypeptide, since the highest degree of identity is concentrated in this region.

We have previously shown that the antibody raised against the whole phage particles of φLf or φXv can react with the particles of the other phage, suggesting that their major coat proteins share a high degree of similarity in amino acid sequence (18). In this study, the anti-φLf pIII was found to cross-react with the φXv pIII. The long identical segments present in the C-terminal half of the pIIIs are likely responsible for the cross-reactivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by grant NSC84-2311-B-005-029 from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck E, Zink B. Nucleotide sequence and genome organization of filamentous bacteriophages fl and fd. Gene. 1981;16:35–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeke J D, Model P. A procaryotic membrane anchor sequence: carboxyl terminus of bacteriophage fl gene III protein retains it in the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5200–5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradbury J F. Genus II. Xanthomonas. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bross P, Bußmann K, Keppner W, Rasched I. Functional analysis of the adsorption protein of two filamentous phages with different host specificities. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:461–471. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-2-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruno R, Bradbury A. A natural longer glycine-rich region in IKe filamentous phage confers no selective advantage. Gene. 1997;184:121–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang K-H, Wen F-S, Tseng T-T, Lin N-T, Yang M-T, Tseng Y-H. Sequence analysis and expression of the filamentous phage φLf gene I encoding a 48-kDa protein associated with host cell membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:313–318. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai H, Chiang K-S, Kuo T-T. Characterization of a new filamentous phage Cf from Xanthomonas citri. J Gen Virol. 1980;46:277–289. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis N G, Boeke J D, Model P. Fine structure of a membrane anchor domain. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenstark A. Bacteriophage techniques. In: Maramorosch K, Koprowski H, editors. Methods in virology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1967. pp. 449–524. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endemann H, Bross P, Rasched I. The adsorption protein of phage IKe. Localization by deletion mutagenesis of domains involved in infectivity. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:471–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu J-F, Chang R-Y, Tseng Y-H. Construction of stable lactose-utilizing Xanthomonas campestris by chromosomal integration of cloned lac genes using filamentous phage φLf. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;37:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill D F, Short N J, Perham R N, Petersen G B. DNA sequence of the filamentous bacteriophage Pf1. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:349–364. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90717-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levengood S K, Webster R E. Nucleotide sequences of the tolA and tolB genes and localization of their products, components of a multistep translocation system in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6600–6609. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6600-6609.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin N-T. Ph.D. thesis. Taichung, Taiwan: National Chung Hsing University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin N-T, Tseng Y-H. The ori of filamentous phage φLf is located within the gene encoding the replication initiation protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:246–251. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin N-T, Tseng Y-H. Sequence and copy number of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris gene encoding 16S rRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:276–280. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin N-T, You B-Y, Huang C-Y, Kuo C-W, Wen F-S, Yang J-S, Tseng Y-H. Characterization of two novel filamentous phages of Xanthomonas. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2543–2547. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin N-T, Wen F-S, Tseng Y-H. A region of the filamentous phage φLf genome that can support autonomous replication and miniphage production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:12–16. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T-J, You B-Y, Lin N-T, Yang M-T, Tseng Y-H. Purification and expression of the gene III protein from filamentous phage φLf. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:113–117. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T-J, Wen F-S, Tseng T-T, Yang M-T, Lin N-T, Tseng Y-H. Identification of gene VI of filamentous phage φLf coding for a 10-kDa minor coat protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:752–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo T-T, Tan M-S, Su M-T, Yang M-K. Complete nucleotide sequence of filamentous phage Cflc from Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2498. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo T-T, Huang T-C, Chow T-Y. A filamentous bacteriophage from Xanthomonas oryzae. Virology. 1969;39:548–555. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Model P, Russel M. Filamentous bacteriophage. In: Calender R, editor. The bacteriophages. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 375–456. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peeter B P H, Peters R M, Schoenmakers J G G, Konings R N H. Nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of the genome of the N-specific filamentous E. coli phage IKe. Comparison with the genome of the F-specific filamentous phages M13, fd, and f1. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:27–39. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapoza M P, Webster R E. The products of gene I and the overlapping in-frame gene XI are required for filamentous phage assembly. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:627–638. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russel M, Whirlow H, Sun T-P, Webster R E. Low-frequency infection of F− bacteria by transducing particles of filamentous bacteriophage. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5312–5316. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5312-5316.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. Bio/Technology. 1993;15:831–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stassen A P M, Schoenmakers E F P M, Yu M, Schoenmakers J G G, Konings R N H. Nucleotide sequence of the filamentous bacteriophage 12-2: module evolution of the filamentous phage genome. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:141–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00182391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stengele I, Bross P, Garcés X, Giray J, Rasched I. Dissection of functional domains in phage fd adsorption protein. Discrimination between attachment and penetration sites. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:143–149. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun T-P, Webster R E. Nucleotide sequence of a gene cluster involved in entry of E colicins and single-stranded DNA of infecting filamentous bacteriophage into Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2667–2674. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2667-2674.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng Y-H, Lo M-C, Lin K-C, Pan C-C, Chang R-Y. Characterization of filamentous bacteriophage φLf from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1881–1884. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-8-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C-S, Vodkin L. Extraction of RNA from tissues containing high levels of procyanidins that bind RNA. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1994;12:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang T-W, Tseng Y-H. Electrotransformation of Xanthomonas campestris by RF DNA of filamentous phage φLf. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1992.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webster R E. The tol gene products and the import of macromolecules into Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1005–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wen F-S. Ph.D. thesis. Taichung, Taiwan: National Chung Hsing University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen F-S, Tseng Y-H. Nucleotide sequence determination, characterization and purification of the single-stranded DNA binding protein and major coat protein of filamentous phage φLf of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:15–22. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen F-S, Tseng Y-H. Nucleotide sequence of the gene presumably encoding the adsorption protein of filamentous phage φLf. Gene. 1996;172:161–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang B-Y, Tsai H-F, Tseng Y-H. Broad host range cosmid pLAFR1 and non-mucoid mutant XCP20 provide a suitable vector-host system for cloning genes in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1988;21:40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang M-K, Yang Y-C. The A protein of the filamentous bacteriophage Cf of Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2840–2844. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2840-2844.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.You B-Y. M.S. thesis. Taichung, Taiwan: National Chung Hsing University; 1993. [Google Scholar]