Abstract

Purpose:

To determine whether there is a difference in the prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration (IPM) across age and genetic etiologies of inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs).

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Methods:

Patients were evaluated at a single tertiary referral center. All patients with a clinical diagnosis of IRD and confirmatory genetic testing were included in this analyses. A total of 392 patients fit inclusion criteria and 151 patients were excluded based on inconclusive genetic testing. Patients were placed into three groups, ciliary and ciliary-related photoreceptor, non-ciliary photoreceptor, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), based on the cellular expression of the gene and the primary affected cell type. The presence of IPM was evaluated through slit lamp biomicroscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and wide-field color fundus photography.

Results:

IPM was seen in 257 of 339 patients (75.8%) with mutations in photoreceptor-specific genes and in 18 of 53 patients (34.0%) with mutations in RPE-specific genes (p<0.0001). Pairwise analysis following stratification by age and gene category suggested a significant difference at all age groups between patients with mutations in photoreceptor-specific genes as compared to patients with mutations in RPE-specific genes (p<0.05). A fitted multivariable logistic regression model was produced and demonstrated that the incidence of IPM increases as a function of both age and gene category.

Conclusions:

IPM is a finding that is more commonly observed in IRDs caused by mutations in photoreceptor-specific genes as compared to RPE-specific genes. The absence of IPM does not always rule out IRD and should raise suspicion for disease mutations in RPE-specific genes.

Introduction

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) refer to a group of rare, heterogeneous disorders that affect an estimated 1 in 2000 individuals worldwide.1,2 These irreversible disorders are currently a leading cause of blindness, and while disease due to biallelic mutations in RPE65 has been successfully treated and other causes of disease are currently being targeted for therapy, the majority of these IRDs are currently untreatable.2,3 Typically, the genetic etiology of these conditions can be traced either to mutations in genes that are expressed within the inner and outer segments of photoreceptors or the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).4 The phenotypic variability associated with these conditions reflects the manner in which photoreceptor and RPE cells respond to disease.5–9 In IRDs involving mutations in genes expressed within the RPE, RPE degeneration may occur as a result of interruption of metabolic function (CYP4V2), accumulation of misfolded protein (C1QTNF5), or unclear mechanism (RPE65).10–13 In contrast, IRDs caused by mutations within photoreceptor genes can lead to the degeneration of photoreceptors as a consequence of the accumulation of toxic substrates (PDE6A/PDE6B), stress-induced apoptosis (RHO), or unknown mechanisms (USH2A).14–16

A hallmark of inherited retinal dystrophies is the appearance of bone spicule pigmentation, caused by the translocation of pigment-containing cells derived from the RPE to the surface of the retina.4 Previously, this intraretinal pigment migration (IPM) was characterized to occur after roughly five years in patients diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa sine pigmento.17 The identification of IPM is particularly important in order to rule out more severe disease such as cancer-associated retinopathy or melanoma-associated retinopathy, which typically have rapid symptomatic progression.18 It was also shown to be relevant in the evaluation of disease severity in patients with recessive Stargardt disease—the appearance of IPM corresponded to a more severe phenotype.19 As such, the appearance of IPM may serve as a critical diagnostic tool and biomarker for disease.

In this study, we compare a large cohort of patients with IRDs caused by mutations in photoreceptor genes and in RPE genes. Specifically, we hypothesized that patients with mutations in RPE specific genes would not have evidence of IPM as mutations in RPE specific genes would lead to primary RPE degeneration as opposed to migration. In contrast, we hypothesized that IPM would be prominent in patients with mutations in photoreceptor specific genes due to photoreceptor degeneration leading to loss of the apposition between photoreceptors and RPE cells, allowing for RPE cells to access the neurosensory retina. Given that genes associated with ciliary disease have been linked to more rapid disease progression, an additional distinction was made between ciliary and ciliary-related genes (CR) and non-ciliary photoreceptor genes (PR) in order to identify potential differences in the prevalence and timing of IPM.20

Methods

Patient Selection

Retrospective chart review was performed of patients seen and evaluated at Columbia University Medical Center between January 2009 and December 2019 who were clinically diagnosed with IRDs and received confirmatory diagnostic genetic testing. Clinical diagnosis of these patients was performed using a combination of complete ophthalmic examination, imaging, and full-field electroretinogram testing. A total of 392 patients were identified who fit inclusion criteria and 151 patients were excluded based on inconclusive genetic testing. Of the 392 patients, a total of 343 patients had a diagnosis with a rod-first pattern of degeneration, including retinitis pigmentosa (RP), late onset-retinal degeneration, Bietti crystalline dystrophy, and choroideremia. The remaining 49 patients had diagnoses of macular, cone, or cone-rod dystrophy. The study was conducted under Columbia University Institutional Review Board approval (protocol AAAR8743) and the need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study design and the minimal risk conferred to patients. All procedures were in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Gene Classification

Patients were separated into one of three categories (CR, PR, and RPE) based primarily on the subcellular localization of the gene product and, if known, the function of the gene implicated in their condition as described in the literature. Genes with protein products localizing to the connecting cilium, including the basal bodies and the ciliary axoneme, the periciliary membrane complex, or the calyceal processes of photoreceptors were labeled as CR genes. All other photoreceptor specific genes were labeled as PR genes. Finally, genes specific to the RPE were labeled as RPE genes. Patients with choroideremia due to mutations in CHM were placed within the RPE cohort as studies have suggested that although choroideremia affects photoreceptors and the RPE independently, choroideremia predominantly affects the RPE.21–23

Intraretinal pigment migration evaluation

Each patient underwent slit lamp biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy of the posterior pole and peripheral retina following pupillary dilation with topical phenylephrine (2.5%) and tropicamide (1%). Afterwards, each patient underwent a series of imaging tests including spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and digital fundus photography or wide-angle color fundus photography using an Optos 200 Tx (Optos, PLC, Dunfermline, United Kingdom). Pigment migration was defined as the visible presence of bone spicule pigmentation in the inner retina. Determination of the presence of IPM was made by slit lamp biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy and corroborated by fundus images and SD-OCT. Fundus photos were evaluated at initial and most recent visit for evidence of IPM. Cases with nummular subretinal pigment deposition were excluded based on evaluation of pigment seen on SD-OCT (Fig. 1).

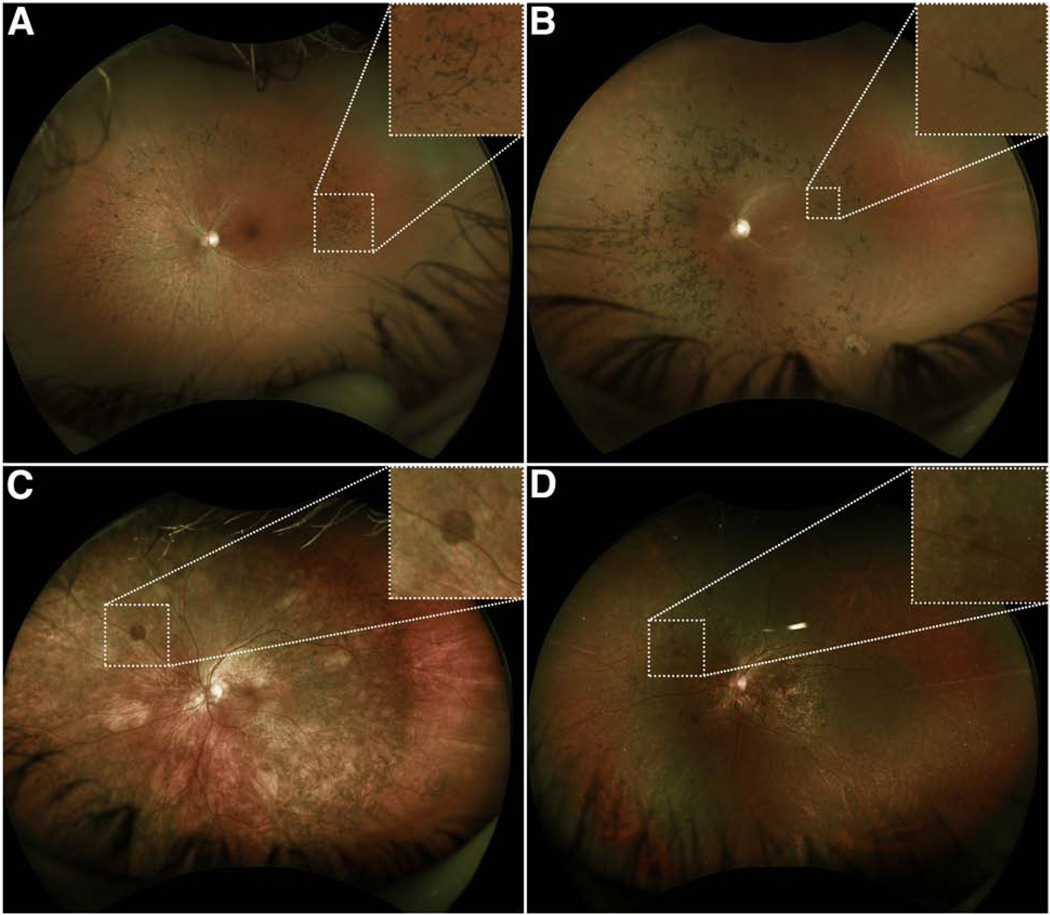

Figure 1. Intraretinal and subretinal pigment visualized on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and color fundus photography.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) images and wide-field color fundus photographs of two patients with mutations in (A) a ciliary gene (MAK) and (B) an RPE-specific gene (CYP4V2) are illustrated. (A) Intraretinal pigment has a bone-spicule like appearance in color fundus photographs and can be visualized on the near-infrared reflectance scan and within the neurosensory retina in the SD-OCT (yellow arrows). (B) In contrast, subretinal pigment appears nummular in color fundus photographs and is seen deposited beneath the outer retinal layers and above the retinal pigment epithelium (yellow arrows). In both cases, posterior shadowing beneath the pigment is seen on SD-OCT.

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 3.6.1 (Vienna, Austria). A Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine whether the prevalence of IPM was independent of the category of gene. Analysis was then repeated to determine whether the prevalence of IPM by category of gene differed following stratification by age. A multivariable logistic regression model using gene category and age category as independent variables was fitted to predict the prevalence of IPM based on gene category and age.

Results

Gene Classification

Identified genetic etiologies of disease in our cohort were mutations in the following genes: PR (CDHR1, CERKL, CNGB1, CRB1, CRX, DHDDS, GUCA1A, GUCA1B, GUCY2D, IMPDH1, KLHL7, NRL, PDE6A, PDE6B, PDE6C, PROM1, PRPF3, PRPF8, PRPF31, PRPH2, RDH12, REEP6, RHO, ROM1, SNRNP200), CR (AHI1, BBS1, BBS10, C21orf2,C2orf71, CDH23, CEP290, CEP78, CLRN1, EYS, FAM161A, GPR98, IFT140, IFT172, KIZ, MAK, MYO7A, NPHP1, PCDH15, RP1, RP2, RPGR, RPGRIP1, SPATA7, TTLL5, TOPORS, TULP1, USH1C, USH2A), and RPE (C1QTNF5, CHM, CYP4V2, LRAT, RDH5, RDH11, RGR, RLBP1, RPE65). A summary of the gene functions and localizations are illustrated in Figure 2 and in Supplemental Table 1 (Supplemental Material at AJO.com).

Figure 2. Cellular localization of genes associated with inherited retinal degenerations.

A diagram of photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) illustrates the various subcellular compartments of the photoreceptors, including the inner and outer segment as well as the connecting cilium and surrounding periciliary areas, which includes the periciliary membrane complex and the calyceal processes. The functions of the inner and outer segment were categorized into photoreceptor morphogenesis, rhodopsin processing, phototransduction and general metabolism and homeostasis. The functions of the connecting cilium were simplified as ciliogenesis, ciliary transport and trafficking, and ciliary structure and stability. Finally, the functions of the RPE were classified as either general homeostasis or associated with the visual cycle.

Patient Summary

A total of 392 patients were evaluated. Within this cohort were 140 patients in the PR group, 199 patients in the CR group, and 53 patients in the RPE group. Within these three groups, 106 patients in the PR group, 184 patients in the CR group, and 53 patients in the RPE group were diagnosed with a type of rod-first degeneration. Mean and median age at initial evaluation was 40 and 37.5 for the PR cohort, 41.3 and 43 for the CR cohort, and 37 and 34 for the RPE cohort respectively. Mean follow-up time for all patients who were seen at more than one visit was 4.09, 3.77, and 2.8 years in these three groups respectively. A summary of the demographic and diagnostic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographics and diagnoses of 392 patients with inherited retinal dystrophy

| Gender | Diagnosis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rod-first degeneration | Cone-first degeneration | ||||||||||

| Male | Female | ARRP | ADRP | XLRP | BCD | LORD | CHM | Cone-Rod Dystrophy | Cone Dystrophy | Macular Dystrophy | |

| PR | 70 | 70 | 52 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 20 |

| CR | 130 | 69 | 144 | 8 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| RPE | 35 | 18 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

PR – patients with mutations in non-ciliary photoreceptor-specific genes, CR – patients with mutations in ciliary and ciliary-related photoreceptor-specific genes, RPE – patients with mutations in retinal pigment epithelium-specific genes, ARRP – autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, ADRP – autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, XLRP – X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, BCD – Bietti Crystalline Dystrophy, LORD – Late Onset Retinal Degeneration, CHM - choroideremia

Intraretinal pigment migration

On evaluation of the PR cohort, a total of 99 of 140 patients (71%) had evidence of IPM at most recent visit. Ninety-five of the 106 patients (90%) with a diagnosis of rod-first degeneration and 4 of the 34 (12%) patients with a diagnosis of cone-first degeneration were found to have IPM in the PR cohort. A total of 158 of 199 patients (79%) had signs of IPM on examination of the CR cohort. Prevalence of IPM in patients with rod-first degeneration was 154 of 184 (84%), as compared to 4 of 15 (27%) in patients with cone-first degeneration within this cohort. In the RPE cohort, the prevalence of IPM was 18 of 53 patients (34%). Two of 14 patients (14%) with RP and 16 of 24 patients (67%) with choroideremia had IPM while no patients with Bietti crystalline dystrophy or late-onset retinal degeneration showed any signs of IPM. Comparison of the three cohorts following stratification by age was performed among the patients with a diagnosis of rod-first degeneration. Patients in each group were divided into five age categories (0–15, 16–30, and 31–45, 46–60, and 61+). The prevalence of IPM by age can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2:

Prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration as stratified by age and gene category in patients with rod-first degeneration

| Age | PR Incidence (%) | CR Incidence (%) | RPE Incidence (%) | Fisher’s Exact Test p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–15* | 10/14 (71%) | 9/23 (39%) | 0/7 (0%) | 0.002 |

| 16–30* | 20/24 (83%) | 26/36 (72%) | 6/15 (40%) | 0.017 |

| 31–45* | 28/30 (93%) | 45/46 (98%) | 4/13 (31%) | 1.22 × 10−7 |

| 46–60* | 17/18 (94%) | 47/50 (94%) | 4/11 (36%) | 5.20 × 10−5 |

| 61+* | 20/20 (100%) | 27/29 (93%) | 4/7 (57%) | 0.006 |

| Cumulative* | 95/106 (90%) | 154/184 (84%) | 18/53 (34%) | 5.97 × 10−14 |

PR - Photoreceptor gene, CR - Ciliary and ciliary-related gene, RPE - Retinal pigment epithelium gene,

statistically significant at p<0.05

A Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine the homogeneity of prevalence of IPM among the three gene categories, yielding a p-value < 1×10−13, suggesting a significant difference. Following further stratification of prevalence rates by age, Fisher’s exact test demonstrated a significant difference in the prevalence of IPM at each age group (p<0.02). Pairwise comparison of gene categories revealed no significant differences between the PR and CR group at any age group, however, significant differences were seen between the PR and RPE cohort at all age groups (p<0.05) and between the CR and RPE cohort at all age groups (p<0.05) except for the groups aged 0–15 and 16–30 years old (Supplemental Data 1, Supplemental Material at AJO.com).

A multivariable logistic regression model was first produced using only gene category as the explanatory variable. The model (Supplemental Data 2 & 3, Supplemental Tables 2–5, Supplemental Material at AJO.com) similarly suggested a statistically significant difference in rates of IPM between the CR and RPE gene categories and the PR and RPE gene categories (p<1×10−10). Predicted prevalence rates of IPM were 0.90, 0.84, and 0.34 among the PR, CR, and RPE gene categories, respectively. The model was then refitted to include age as an additional explanatory variable and revealed persistent statistical significance in the prevalence of IPM between the gene categories. Moreover, it also suggested that prevalence of IPM increases with age (p<1×10−14). A summary of the predicted prevalence rates by gene category and age grouping are found in Table 3 and their respective odds ratios are illustrated in Supplemental Figure 1 (Supplemental Material at AJO.com).

Table 3:

Predicted incidence of pigment migration in patients with rod-first degeneration by age and gene category using a fitted regression model

| Age | PR Incidence (95% CI) | CR Incidence (95% CI) | RPE Incidence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–15 | 0.61 (0.41, 0.78) | 0.44 (0.28, 0.61) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.13) |

| 16–30 | 0.87 (0.75, 0.94) | 0.78 (0.65, 0.87) | 0.20 (0.10, 0.36) |

| 31–45 | 0.96 (0.90, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.84, 0.96) | 0.45 (0.26, 0.65) |

| 46–60 | 0.96 (0.89, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.83, 0.96) | 0.44 (0.25, 0.65) |

| 61 + | 0.97 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.95 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.57 (0.30, 0.80) |

PR - Photoreceptor gene, CR - Ciliary and ciliary related gene, RPE - Retinal pigment epithelium gene, 95% CI - 95% confidence interval

Discussion

IPM is a defining feature of IRDs. These clumps of pigment are known to be derived from RPE cells that detach from Bruch’s membrane and migrate towards the inner retina following the degeneration of photoreceptors and loss of RPE-photoreceptor connection.4,24,25 Despite detailed histologic understanding of what constitutes this classic pathologic finding, the mechanism and pathophysiology of IPM is poorly understood.4 Prior studies in RP models have suggested the role of vascular affinity of RPE cells while others have implicated the inactivation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway (PI3K) pathway.4,24,26 Studies of the migration of RPE cells into the vitreous cavity in proliferative vitreoretinopathy have suggested that the process is dependent on a number of factors including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR)/PI3K/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling.27–29

To date, the classification of IRDs and their phenotypes has typically been according to inheritance pattern.3,30,31 Fishman et al. first correlated prognosis with pattern of inheritance, showing that autosomal dominant RP had the mildest manifestations, followed by autosomal recessive RP, and most severely X-linked RP.3,30,31 The gene-specific treatment of IRDs is also closely tied to the inheritance pattern, as both recessive and X-linked conditions require the introduction of one functional allele, whereas dominant mutations, such as those that behave in a dominant negative fashion, impair the function of the normal allele and necessitate a more complex intervention.32–34

Despite these factors, there lies an argument for a greater emphasis on the functional grouping of IRD etiologies, as both disease pathophysiology and mechanism are dependent on the causative gene.35,36 This has been previously suggested in the literature, and prior studies of ciliopathies as compared to non-ciliopathies involving the retina have shown a more rapid phenotypic progression in ciliopathies.19,35,36 In this study, we examined differences in IPM across functional categories and suggested a role for IPM as a biomarker in candidate gene testing and the characterization of disease progression.

A statistically significant difference in prevalence of IPM was seen among the three categories (p<1×10−13) with the lowest prevalence of IPM found in patients with mutations in RPE genes. The absence of IPM in the RPE group was consistent with the hypothesis that in retinal diseases caused by RPE-specific genes, RPE cells may undergo degeneration prior to secondary photoreceptor loss. Consequently, because the RPE degenerates while it remains apposed to intact photoreceptors, it is likely that they are not able to physically penetrate through the neurosensory retina due to contact inhibition by the intact photoreceptor cell-RPE complex.4,20,37 By the time secondary photoreceptor loss occurs, the RPE cells have already degenerated to a point where they are unable to undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition and respond to PTEN inactivation and other stimuli that draw them towards the inner retina.26,38 Notably, several patients in the RPE cohort, in particular those diagnosed with Bietti crystalline dystrophy and RGR-mediated retinal dystrophy, were found to have evidence of nummular subretinal pigment clumping seen as deposits underneath the branch retinal veins and arteries on color fundus photographs (Fig. 3) SD-OCT images through such pigment in several patients with BCD confirmed that these pigment were subretinal in all observed cases (Fig. 4). Limitations of this analysis include the possibility that the presence of intraretinal pigment was not identified through the combination of dilated fundus examination and wide-field color fundus photography, especially in the periphery of severely progressive disorders such as Bietti crystalline dystrophy and late-onset retinal degeneration. Further studies utilizing SD-OCT imaging in the far periphery will help confirm that these pigment clumps are subretinal even in the periphery.

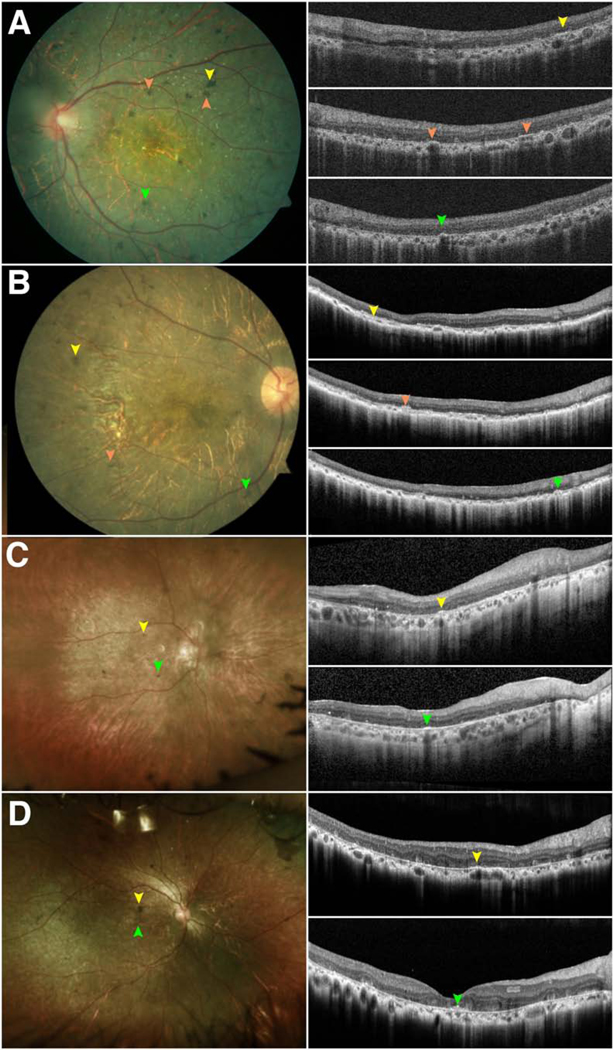

Figure 3. Intraretinal pigment migration in comparison with subretinal pigment migration near the branch vessels on color fundus photographs.

Wide-field color fundus photos of patients with (A) a mutation in a phototransduction gene (RHO) and (B) mutations in a ciliary gene (USH2A) demonstrated the presence of intraretinal pigment overlying the ophthalmic veins, confirming that the pigment is anterior to the neurosensory retina. In contrast, fundus photos of patients with (C & D) mutations in RPE-specific genes, RGR and CYP4V2 respectively, demonstrated the presence of pigment below the vessels, suggestive of subretinal pigment.

Figure 4. Subretinal pigment migration as seen on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with Bietti crystalline dystrophy.

Color fundus photographs and optical coherence tomography of four patients with Bietti crystalline dystrophy (A-D) demonstrate that the foci of pigment on color photographs spatially correlate with subretinal deposits (arrows) on optical coherence tomography as opposed to intraretinal deposits.

Of the 18 patients within the RPE cohort who were found to have IPM, 16 patients had a clinical diagnosis of choroideremia. The relatively high prevalence of IPM in choroideremia as compared to the other rod-cone degenerations may be explained by the unique pathophysiology of choroideremia. Choroideremia is found to be expressed in both photoreceptors and RPE cells, and while it is currently believed that the disease predominantly affect the RPE prior to photoreceptors, prior studies have suggested that the degeneration of the two cells occurs, to some degree, independently of one another.21–23 Therefore, we hypothesize that the intraretinal pigment seen in patients with choroideremia, may occur at foci of the retina where photoreceptors degenerate concurrently or prior to RPE degeneration. This is in contrast to many other forms of IRDs, where degeneration of one cell type typically precedes the other.

No statistically significant difference was seen between the PR and CR groups overall. However, a relatively high prevalence of IPM was seen in the PR group (71%) as compared to the CR group (39%) at ages 0–15. Prior studies have shown that ciliary dysfunction causes defects in RPE maturation that predate photoreceptor death, which suggests a potential mechanism for why IPM may develop more slowly and later on in the CR group as compared to the PR group.39 Limitations of this analysis include the small number of patients in each age group following stratification and future evaluation of a larger cohort of patients may help elucidate a significant difference between these two groups.

Finally, a multivariable logistic regression model was produced to predict prevalence of IPM taking into account both age and gene category. This model corroborated that the prevalence of IPM was significantly higher in the CR and PR groups as compared to the RPE group and that prevalence of IPM increases with age. Notably, deviance testing of the interaction between age and gene on IPM was found to be insignificant; however, the implementation of age to the model results in a profound shift in the predicted prevalence of IPM based on gene category, suggesting that patient age may have an underlying effect on gene function as it relates to the development of IPM. Further mechanistic studies on the effects of age on various gene functions will be valuable in refining this model. Limitations of this predictive model include its fitting based on this specific cohort, and analysis of a larger cohort of patients will help validate the accuracy of the model. Additionally, the model does not take into consideration additional confounding factors which may influence the prevalence of pigment migration and the interactions between such factors.

IPM is a defining feature in several inherited retinal dystrophies, and the prevalence of pigment development was shown in this study to be a function of both age and gene category. In patients with mutations in PR or CR gene mutations, the fitted logistic regression model may serve as a predictor for the timeline and development of pigment in patients, supporting the use of IPM as a possible biomarker for monitoring disease progression and as a potential outcome measurement in future treatments that involve early intervention before appreciable pigmentary changes. Similarly, the lack of IPM seen in patients with RPE-specific gene mutations as compared to those with PR or CR gene mutations may be helpful to guide candidate gene testing.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Odds ratio of the prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration based on predictive modeling. The odds ratios (OR) of the predicted prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration based on our binary logistic regression model demonstrate an OR of 1.99 when comparing the non-ciliary photoreceptor and ciliary & ciliary-related cohort, 0.07 when comparing the retinal pigment epithelium and ciliary & ciliary-related cohort, and 0.04 when comparing the retinal pigment epithelium and non-ciliary photoreceptor cohorts. The 95% confidence intervals of the OR are also illustrated.

Highlights.

Pigment migration is prevalent in diseases due to mutations in photoreceptor genes.

Pigment migration is rare in diseases caused by mutations in RPE genes.

Age has an effect on gene function in the development of pigment migration.

Pigment migration is less common in young patients with ciliary gene mutations.

Acknowledgments/Disclosure

a. Funding/Support

Funding for this research was supported by the Jonas Children’s Vision Care and Bernard & Shirlee Brown Glaucoma Laboratory are supported by the National Institute of Health 5P30CA013696, U01 EY030580, U54OD020351, R24EY028758, R24EY027285, 5P30 EY019007, R01EY018213, R01EY024698, R01EY024091, R01EY026682, R21AG050437, the Schneeweiss Stem Cell Fund, New York State [SDHDOH01-C32590GG-3450000 ], the Foundation Fighting Blindness New York Regional Research Center Grant [PPA-1218-0751-COLU], Nancy & Kobi Karp, the Crowley Family Funds, The Rosenbaum Family Foundation, Alcon Research Institute, the Gebroe Family Foundation, the Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) Physician-Scientist Award, unrestricted funds from RPB, New York, NY, USA. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

b. Financial Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures.

c. Other Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our consulting ophthalmic bio-statistician Jimmy K. Duong from the Department of Biostatistics at Columbia University for validating our proposed model.

Footnotes

CRediT Author Statement

Jin Kyun Oh: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft

Sarah R. Levi: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft

Joonpyo Kim: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Jose Ronaldo Lima de Carvalho: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Joseph Ryu: Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Validation

Janet R. Sparrow: Writing – Review & Editing, Conceptualization, Supervision

Stephen H. Tsang: Writing – Review & Editing, Conceptualization, Project Administration

Supplemental Material available at AJO.com

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.McClements ME, MacLaren RE. Gene therapy for retinal disease. Transl Res. 2013;161(4):241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cremers FPM, Boon CJF, Bujakowska K, Zeitz C. Special Issue Introduction: Inherited Retinal Disease: Novel Candidate Genes, Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, and Inheritance Models. Genes (Basel). 2018;9(4):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maguire AM, Russell S, Wellman JA, et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl in RPE65 Mutation-Associated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: Results of Phase 1 and 3 Trials. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(9):1273–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verbakel SK, van Huet RAC, Boon CJF, den Hollander AI, Collin RWJ, Klaver CCW, Hoyng CB, Roepman R, Klevering BJ. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;66:157–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li ZY, Possin DE, Milam AH. Histopathology of bone spicule pigmentation in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(5):805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Hollander AI, Black A, Bennett J, Cremers FP. Lighting a candle in the dark: advances in genetics and gene therapy of recessive retinal dystrophies [published correction appears in J Clin Invest. 2011 Jan 4;121(1):456–7]. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3042–3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roosing S, Thiadens AAHJ, Hoyng CB, Klaver CCW, den Hollander AI, Cremers FPM. Causes and consequences of inherited cone disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014;42:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saari JC. Vitamin A metabolism in rod and cone visual cycles. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:125–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis GH, Golczak M, Moise AR, Palczewski K. Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:469–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparrow JR, Hicks D, Hamel CP. The retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10(9):802–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-García GP, Martínez-Rubio M, Moya-Moya MA, Pérez-Santonja JJ, Escribano J. Current perspectives in Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:1379–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodruff M, Wang Z, Chung H. et al. Spontaneous activity of opsin apoprotein is a cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 2003;35:158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shu X, Tulloch B, Lennon A, et al. Disease mechanisms in late-onset retinal macular degeneration associated with mutation in C1QTNF5. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(10):1680–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galy A, Roux MJ, Sahel JA, Léveillard T, Giangrande A. Rhodopsin maturation defects induce photoreceptor death by apoptosis: a fly model for RhodopsinPro23His human retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(17):2547–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lolley R, Farber D, Rayborn M, Hollyfield J. Cyclic GMP accumulation causes degeneration of photoreceptor cells: simulation of an inherited disease. Science. 1977;196(4290):664–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dona M, Slijkerman R, Lerner K, et al. Usherin defects lead to early-onset retinal dysfunction in zebrafish. Exp Eye Res. 2018;173:148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi VKL, Takiuti JT, Jauregui R, Mahajan VB, Tsang SH. Rates of Bone Spicule Pigment Appearance in Patients With Retinitis Pigmentosa Sine Pigmento. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;195:176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grewal DS, Fishman GA, Jampol LM. Autoimmune retinopathy and antiretinal antibodies: a review. Retina. 2014;34(5):827–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong X, Strauss RW, Cideciyan AV, Michaelides M, Sahel JA, Munoz B, Ahmed M, Ervin AM, West SK, Cheetham JK, Scholl HPN, ProgStar Study G. Visual Acuity Change over 12 Months in the Prospective Progression of Atrophy Secondary to Stargardt Disease (ProgStar) Study: ProgStar Report Number 6. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1640–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahash VKL, Xu CL, Takiuti JT, Apatoff MBL, Duong JK, Mahajan VB, Tsang SH. Comparison of structural progression between ciliopathy and non-ciliopathy associated with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolmachova T, Anders R, Abrink M, et al. Independent degeneration of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium in conditional knockout mouse models of choroideremia. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):386–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue K, Oldani M, Jolly JK, et al. Correlation of Optical Coherence Tomography and Autofluorescence in the Outer Retina and Choroid of Patients With Choroideremia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(8):3674–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue K, MacLaren RE. Ocular gene therapy for choroideremia: clinical trials and future perspectives. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2018;13(3):129–138. doi: 10.1080/17469899.2018.1475232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milam AH, Li ZY, Fariss RN. Histopathology of the human retina in retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17(2):175–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuerch K, Marsiglia M, Lee W, Tsang SH, Sparrow JR. MULTIMODAL IMAGING OF DISEASE-ASSOCIATED PIGMENTARY CHANGES IN RETINITIS PIGMENTOSA. Retina. 2016;36 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S147–S158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JW, Kang KH, Burrola P, Mak TW, Lemke G. Retinal degeneration triggered by inactivation of PTEN in the retinal pigment epithelium. Genes Dev. 2008;22(22):3147–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin M, He S, Worpel V, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Promotion of adhesion and migration of RPE cells to provisional extracellular matrices by TNF-alpha. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(13):4324–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen XD, Su MY, Chen TT, Hong HY, Han AD, Li WS. Oxidative stress affects retinal pigment epithelial cell survival through epidermal growth factor receptor/AKT signaling pathway. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(4):507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Wang F, Jiang Y, Xu S, Lu F, Wang W, Sun X, Sun X. Migration of retinal pigment epithelial cells is EGFR/PI3K/AKT dependent. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2013;5:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishman GA. Retinitis pigmentosa. Visual loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(7):1185–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishman GA, Farber MD, Derlacki DJ. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Profile of clinical findings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(3):369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiCarlo JE, Mahajan VB, Tsang SH. Gene therapy and genome surgery in the retina. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(6):2177–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi VKL, Takiuti JT, Jauregui R, Tsang SH. Gene therapy in inherited retinal degenerative diseases, a review. Ophthalmic Genet. 2018;39(5):560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang DJ, Xu CL, Tsang SH. Revolution in Gene Medicine Therapy and Genome Surgery. Genes (Basel). 2018;9(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelan JK, Bok D. A brief review of retinitis pigmentosa and the identified retinitis pigmentosa genes. Mol Vis. 2000;6:116–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dias MF, Joo K, Kemp JA, et al. Molecular genetics and emerging therapies for retinitis pigmentosa: Basic research and clinical perspectives. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;63:107–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin S, Rodrigues GA. Progress and perspectives on the role of RPE cell inflammatory responses in the development of age-related macular degeneration. J Inflamm Res. 2008;1:49–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamiya S, Liu L, Kaplan HJ. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Proliferation of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Initiated upon Loss of Cell-Cell Contact. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2755–2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May-Simera HL, Wan Q, Jha BS, et al. Primary Cilium-Mediated Retinal Pigment Epithelium Maturation Is Disrupted in Ciliopathy Patient Cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22(1):189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Odds ratio of the prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration based on predictive modeling. The odds ratios (OR) of the predicted prevalence of intraretinal pigment migration based on our binary logistic regression model demonstrate an OR of 1.99 when comparing the non-ciliary photoreceptor and ciliary & ciliary-related cohort, 0.07 when comparing the retinal pigment epithelium and ciliary & ciliary-related cohort, and 0.04 when comparing the retinal pigment epithelium and non-ciliary photoreceptor cohorts. The 95% confidence intervals of the OR are also illustrated.