Abstract

Background

In Mexico, the incidence of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has increased in the last few years. Mortality is higher than in developed countries, even though the same chemotherapy protocols are used. CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA) mutations are recurrent in AML, influence prognosis, and help to define treatment strategies. CEBPA mutational profiles and their clinical implications have not been evaluated in Mexican pediatric AML patients.

Aim of the Study

To identify the mutational landscape of the CEBPA gene in pediatric patients with de novo AML and assess its influence on clinical features and overall survival (OS).

Materials and Methods

DNA was extracted from bone marrow aspirates at diagnosis. Targeted massive parallel sequencing of CEBPA was performed in 80 patients.

Results

CEBPA was mutated in 12.5% (10/80) of patients. Frameshifts at the N-terminal region were the most common mutations 57.14% (8/14). CEBPA biallelic (CEBPABI) mutations were identified in five patients. M2 subtype was the most common in CEBPA positive patients (CEBPAPOS) (p = 0.009); 50% of the CEBPAPOS patients had a WBC count > 100,000 at diagnosis (p = 0.004). OS > 1 year was significantly better in CEBPA negative (CEBPANEG) patients (p = 0.0001). CEBPAPOS patients (either bi- or monoallelic) had a significantly lower OS (p = 0.002). Concurrent mutations in FLT3, CSF3R, and WT1 genes were found in CEBPAPOS individuals. Their contribution to poor OS cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

CEBPA mutational profiles in Mexican pediatric AML patients and their clinical implications were evaluated for the first time. The frequency of CEBPAPOS was in the range reported for pediatric AML (4.5–15%). CEBPA mutations showed a negative impact on OS as opposed to the results of other studies.

Keywords: CEBPA, pediatric, Mexican, AML, survival, risk-stratification

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and accumulation of immature myeloid precursor cells in the bone marrow, which leads to impaired hematopoiesis and bone marrow failure (1).

Acute myeloid leukemia is the second most common cancer in Mexican children. Its incidence has increased in the last years, and its mortality is higher than in developed countries even though the same chemotherapy protocols are used (2–4). AML accounts for 15–20% of leukemia-related mortality (5). Only 30% of patients achieve complete remission. This figure is significantly lower than the 90–95% reported literature (6). Mortality at the beginning of treatment is also higher than expected (7).

Several extensive sequencing studies on AML revealed the genetic heterogeneity of the disease: on average, 13 mutations were detected per patient, and at least 23 recurrently mutated genes were found (8). Some recurrent chromosomal translocations and somatic gene mutations are already included in clinical guidelines as biomarkers to improve disease classification, prognostic categorization, and definition of treatment strategies (9, 10).

CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA) is one of the recurrently mutated genes in both adult (7–16%) (11, 12) and pediatric (5–15%) AML patients (13–15). The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms includes two distinct CEBPA-related disease entities: AML with biallelic CEBPA mutations (CEBPABI) and AML with germline CEBPA mutations. Germline CEBPA mutations at N- and C-terminal protein domains have been described. They may lead to familial CEBPABI AML after acquiring a second hit in the CEBPA gene (9).

CEBPA encodes the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha, a lineage-specific basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor required to form myeloid progenitors from multipotent hematopoietic stem cells. It is expressed at high levels during myeloid cell differentiation. It binds to the promoters of multiple genes during myeloid linage maturation (16).

The CEBPA protein contains two transactivation domains (TADs) at its N-terminus, a DNA binding domain, and a basic leucine zipper at the C-terminus responsible for DNA binding and dimerization. CEBPA gene is located on chromosome 19q13.1 and has only one exon. It is transcribed into a single mRNA, translated into two isoforms by alternative start codon usage: a 42-kDa full isoform (p42) or a truncated 30-kDa (p30) isoform lacking the TAD1 domain. Both isoforms can make homo- or heterodimers with other proteins and participate in myeloid differentiation and other cellular processes (12).

As in most Latin American countries, extensive tumoral profiling is not routinely performed in Mexico; therefore, the information about the mutational profiles and their possible impact on outcomes in pediatric or adult patients is scarce or not available. Using real-time PCR methodology or FISH, molecular testing is limited to the most common fusions described in AML and acute lymphocytic leukemia. This study aims to explore the mutational profile of the CEBPA gene in a group of pediatric de novo AML patients and to evaluate the possible impact on clinical features and overall survival (OS).

Materials and Methods

Population

This study analyzed 80 patients with de novo AML. They were diagnosed between March 2010 and March 2018. The diagnosis was made at each institution by bone marrow aspirate and immunophenotype. Bone marrow samples were obtained at the time of diagnosis and submitted to the Mexican Inter-Institutional Group for Identifying Childhood Leukemia Causes in Mexico City. Data were collected from medical charts, including sex, age, peripheral white blood cell count, percentage of bone marrow blasts at diagnosis, FAB (French-American-British) classification, and treatment protocol. The clinical features of the analyzed patients had been previously reported in Molina et al. (17).

Risk classification at diagnosis was assigned based mainly on morphology; in most public hospitals in Mexico City, cytogenetics and minimal residual disease detection are unavailable. The risk groups were established as follows: standard-risk group: M1, M2, and M4 (with at least 3% of eosinophils); high-risk group: M4 (with less than 3% of eosinophils) and M5. Additionally, in one hospital, more than 5% of blasts in bone marrow on day 15 was used to identify patient with high-risk features. In M3 patients low-risk group includes patients with white blood cell count (WBC) < 10 × 109 and platelets > 40 × 109; for intermedia-risk group WBC count < 10 × 109 and platelets < 40 × 109 and for high-risk group WBC ≥ 10 × 109.

Patients were classified with an intermediate risk when MRD level by flow cytometry was >0.1% after course 1, but fell to <0.1% after course 2. Some child’s parents covered this test in a private laboratory.

The ethics and scientific review boards of the National Institute of Genomic Medicine, Mexico City, Mexico, approved this study (document number 28-2015-1). All human samples and clinical information were approved for the present study. The children’s parents signed the informed consent obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA Extraction

The DNA was extracted from bone marrow samples with Maxwell® 16 Blood DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The DNA purity and concentration were measured with NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States).

Next-Generation Sequencing

CEBPA sequencing was performed with the “Myeloid solution” panel by Sophia Genetics (Sophia Genetics SA, Saint-Sulpice, Switzerland). Library preparation and sequencing were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were pooled and sequenced on a MiSeq System v3 chemistry (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Sequence data were analyzed with the Sophia DDM® software version 5.2.7.1 (Sophia Genetics SA, Saint-Sulpice, Switzerland). Deep sequencing was greater than 500X for all the target regions. Variant Fraction (VF) was calculated for each mutation by dividing the number of sequencing reads showing the mutation by the total sequencing read at the mutation position.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed as described previously (17). For dichotomic variables, chi-square or two-sided’ Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions among different groups. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was applied for continuous variables, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed with the SPSS software package, SPSS v21 (Chicago, IL, United States).

The Kaplan-Meier method (18) was used to assess overall survival (OS). The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between survival distributions with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The OS time was calculated from the day diagnosis was confirmed to either the last follow-up or death from any cause. Patients who did not experience an event were censored at the last follow-up. Those who did not attend follow-up appointments were censored at the date of the last known contact.

The maternal years of education were used as socioeconomic status (SES) indicator to evaluate if it impacted the inferior OS observed. The patients were further categorized in CEBPA (positive/negative) and death (yes/no) to identify possible associations. As per the categorization used by the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium, SES was assigned as follows: [0–9 years (low SES), 9.1–12.9 years (reference category), ≥13 years of education (high SES)] (19, 20). The exact Fisher’s test was used to assess the difference between groups.

Results

Demographic and Biological Characteristics of the Patients

Demographic, clinical, and the main biological characteristics of the patients were previously reported (17). Fifty-five percent of the patients were male. The age at diagnosis was similar in both sexes; the mean age at diagnosis was 9.3 years (range 0.4–17.5). Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) M3 was the most prevalent subtype (36.3%), followed by M2 (33.8%). M0, M5, and M6 were the less common subtypes. The mean OS in the study population was 1.95 years.

The patients were treated based on one of the following four protocols: BFM-1998, BFM-2001 (Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster 1998 and 2001), NOPHO-AML93 (Nordic Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology), or PETHEMA-APL-05 (Spanish Program of Treatments in Hematology). APL patients were treated according to the PETHEMA-APL-05 protocol. None of the patients received an allogeneic or autologous bone marrow transplant. Treatment information and the impact of treatment on OS have been previously reported (17).

CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha Mutational Profile in Mexican Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients

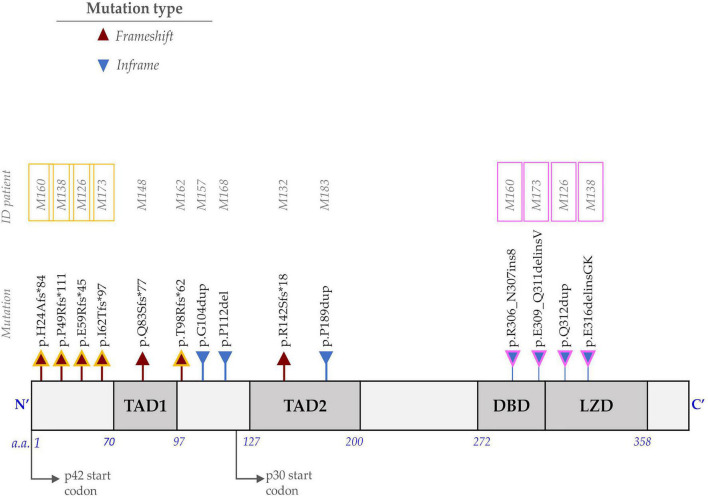

CEBPA was mutated in 12.5% (10/80) of the cases (CEBPAPOS). A total of 14 different mutations were identified. The mutational profile is shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The most common mutations were frameshifts located at the N-terminus of the protein 57.14% (8/14). Biallelic CEBPA mutations (CEBPABI) were identified in five patients, which accounted for 50% of the CEBPAPOS cases. All identified mutations were uploaded to the ClinVar database (accession numbers for submission SUB11180409 are SCV002104196-SCV002104210)1.

TABLE 1.

Mutational overview of the CEBPA gene in Mexican patients with pediatric AML.

| Patient ID | Coding consequence | cDNA | Protein consequence | VF (%) | COSMIC ID | dbSNP | Co-occurring mutations |

| M160 | frameshift | c.68dupC | p.His24Alafs*84 | 39.2 | COSM18922 | rs137852729 | NRAS, ZRSR2, EZH2 |

| inframe_24 | c.918_919ins24 | p.Arg306_Asn307ins8 | 42.8 | Novel | / | ||

| M138 | frameshift | c.146delC | p.Pro49Argfs*111 | 50.5 | COSM5064965 | / | WT1, CALR, PTPN11 |

| inframe_3 | c.946_947insGGA | p.Glu316delinsGlyLys | 48.2 | Novel | / | ||

| M173 | frameshift | c.180_183delGTCC | p.Ile62Thrfs*97 | 44.8 | Novel | / | ASXL1 |

| inframe_6 | c.926_932delAGACGCAinsT | p.Glu309_Gln311delinsVal | 42.7 | Novel | / | ||

| M126 | frameshift | c.174_184delCGAGACGTCCA | p.Glu59Argfs*45 | 49.2 | COSM29261 | / | FLT3, CSF3R, CALR, PTPN11 |

| inframe_3 | c.934_936dupCAG | p.Gln312dup | 49.6 | COSM18466 | / | ||

| M162 | frameshift | c.292delA | p.Thr98Argfs*62 | 94.4 | Novel | / | CSF3R |

| M148 | frameshift | c.247delC | p.Gln83Serfs*77 | 42.5 | COSM1375 | / | FLT3, WT1, PTPN11 |

| M132 | frameshift | c.426delG | p.Arg142Serfs*18 | 48.7 | Novel | / | IDH2 |

| M157 | inframe_3 | c.311_313dupGCG | p.Gly104dup | 1.8 | / | rs780345232 | RUNX1, PTPN11 |

| M168 | inframe_3 | c.334_336delCCC | p.Pro112del | 1.3 | Novel | / | ETV6 |

| M183 | inframe_3 | c.564_566dupGCC | p.Pro189dup | 1.2 | Novel | / | FLT3, TET2, RUNX1, CBL |

VF, variant fraction; COSMIC, catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer; NM_004364 was used for variant annotation.

FIGURE 1.

Representation of the protein encoded by the CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA) gene and the identified mutations. The N-terminus consists of two transactivation domains (TAD1 and TAD2). The carboxyl end (C-terminus) includes the DBD (DNA-binding domain) and the LZD (leucine zipper domain). The frameshift mutations (red triangle) at the N-terminus affect the translation of the p42 isoform and favor the overexpression of the p30 isoform. In-frame mutations (blue triangle) at the C-terminus alter the DNA binding or dimerization process. Individuals with CEBPABI (M160, M138, M126, and M173) have one mutation at the N-terminus (outlined in yellow) and one at the C-terminus (outlined in pink), whereas M162 is homozygous for p.Thr98Argfs*62.

Five germline variants were also identified: His191His (27.5%), Thr230Thr (5%), Hist195_Pro196 (5%), and Pro204Pro (1.2%). They were classified as benign or likely benign according to the ACMG criteria (21). The variant pGly223Ser located between the TAD2 and BDB domains was identified in one individual (1.2%, VF = 47.5%). It is listed in the ClinVar database (Variation ID 239926) and shows conflict regarding its clinical significance (uncertain significance vs. likely benign). According to the gnomAD v3 population database, its global frequency is 0.0004189 (58 of 138,460 alleles), with a maximum allele frequency of 0.004221 (56 of 13,266) in the Latino subpopulation. It has been identified in adults only2 (as of March 2022). The frequency in a local exome database of Mexican individuals is 1.1%. This frequency exceeds the prevalence of a pathogenic variant causing CEBPA-associated familial AML (22). The variant has not been reported in cases of familial AML. It is predicted benign for most in silico algorithms, although no functional studies have been performed. Considering the available information, we classified this variant as likely benign.

Distribution of Demographic and Biological Features Between CEBPAPOS and CEBPANEG Patients

Sex distribution, FAB classification, treatment protocol, risk assessment, WBC count, age, and blast percentage in bone marrow at diagnosis were stratified according to the presence of CEBPA mutations. The results are shown in Table 2. A non-significant (NS) higher proportion of male patients was found in the CEBPAPOS subgroup (60 vs. 54.3% in CEBPANEG group, p = NS). Statistically significant differences were found in the FAB subtype distribution. M2 was the most common among CEBPAPOS patients (70 vs. 28.6% in CEBPANEG p = 0.009). CEBPAPOS patients had significantly higher WBC counts at diagnosis: 50% of CEBPAPOS patients had a WBC count > 100,000, compared with 12.9% in the CEBPANEG group (p = 0.004).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of demographic and biological features between CEBPAPOS and CEBPANEG patients.

|

CEBPAPOS N = 10 |

CEBPANEG N = 70 |

p | |||

| Sex | aN | % | N | % | |

| Female | 4 | 40 | 32 | 45.7 | |

| Male | 6 | 60 | 38 | 54.3 | |

| Mean age at bDx | Years | Range | Years | Range | |

| Female | 9.24 | 4.9 - 10.1 | 9.4 | 0.4 - 17.5 | |

| Male | 9.7 | 5.3 - 15.9 | 9.1 | 1.3 - 16.6 | |

| Total | 9.6 | 4.9 - 15.9 | 9.3 | 0.4 - 17.5 | |

| Mean cBM blast at Dx | Mean (%) | Range | Mean (%) | Range | |

| 84.3 | 65 - 98 | 75.9 | 23 - 100 | ||

| dWBC count at Dx/mm3 | N | % | N | % | |

| <11,000 | 2 | 20 | 29 | 41.4 | |

| 11,000–100,000 | 3 | 30 | 32 | 45.7 | |

| >100,000 | 5 | 50 | 9 | 12.9 | 0.004 |

| dWBC median at Dx/mm3 | N | Median mm3 | N | Median mm3 | |

| <11,000 | 2 | 5000 | 29 | 4300 | |

| 11,000–100,000 | 3 | 42400 | 32 | 34450 | |

| >100,000 | 5 | 249000 | 9 | 146100 | |

| Total | 10 | 117630 | 70 | 18830 | |

| Mean overall survival | N | Years | N | Years | |

| OS | 10 | 0.9 | 69 | 1.97 | |

| OS ≤ 1 year | 5 (50%) | 0.3 | 25 (36.2%) | 0.35 | |

| OS > 1 year | 5 (50%) | 1.8 | 44 (63.8%) | 3.1 | 0.0001 |

| OS ≤ 2 year | 8 (80%) | 0.8 | 40 (58%) | 0.8 | |

| OS > 2 year | 2 (20%) | 2.1 | 29 (42%) | 3.9 | 0.0258 |

| eFAB subtypes | N | % | N | % | |

| M0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| M1 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 11.4 | |

| M2 | 7 | 70 | 20 | 28.6 | 0.009 |

| M3 | 2 | 20 | 27 | 38.6 | |

| M4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 17.1 | |

| M5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| M6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Treatment protocols | N | % | N | % | |

| fBFM-1998 | 4 | 40 | 21 | 30 | |

| BFM-2001 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| gNOPHO-AML93 | 2 | 20 | 18 | 25.7 | |

| hPETHEMA-APL-05 | 2 | 20 | 27 | 38.6 | |

| Risk classification at Dx. | N | % | N | % | |

| Standard | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8.6 | |

| Intermediate | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| High | 5 | 50 | 39 | 55.7 | |

| Not classified | 5 | 50 | 21 | 30 | |

| Achievement of iCR | N | % | N | % | |

| 10 | 100 | 67 | 95.7 | ||

| Relapsed | N | % | N | % | |

| 3 | 30 | 4 | 5.7% | ||

aN, number of patients; bDx, diagnosis; cBM, bone marrow; dWBC, white blood cell; eFAB, French-American-British classification; fBFM, Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster; gNOPHO, Nordic Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology; hPETHEMA, Spanish Program of Treatments in Hematology; iCR, complete remission assessed on day 28. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Impact of CEBPA Mutation on Overall Survival

A significantly higher mean OS was observed in CEBPANEG patients considering 1 year after diagnosis (3.1 years in CEBPANEG vs. 1.8 years in CEBPAPOS, p = 0.0001) or 2 years (2.1 years in CEBPAPOS vs. 3.9 years in CEBPANEG, p = 0.0258).

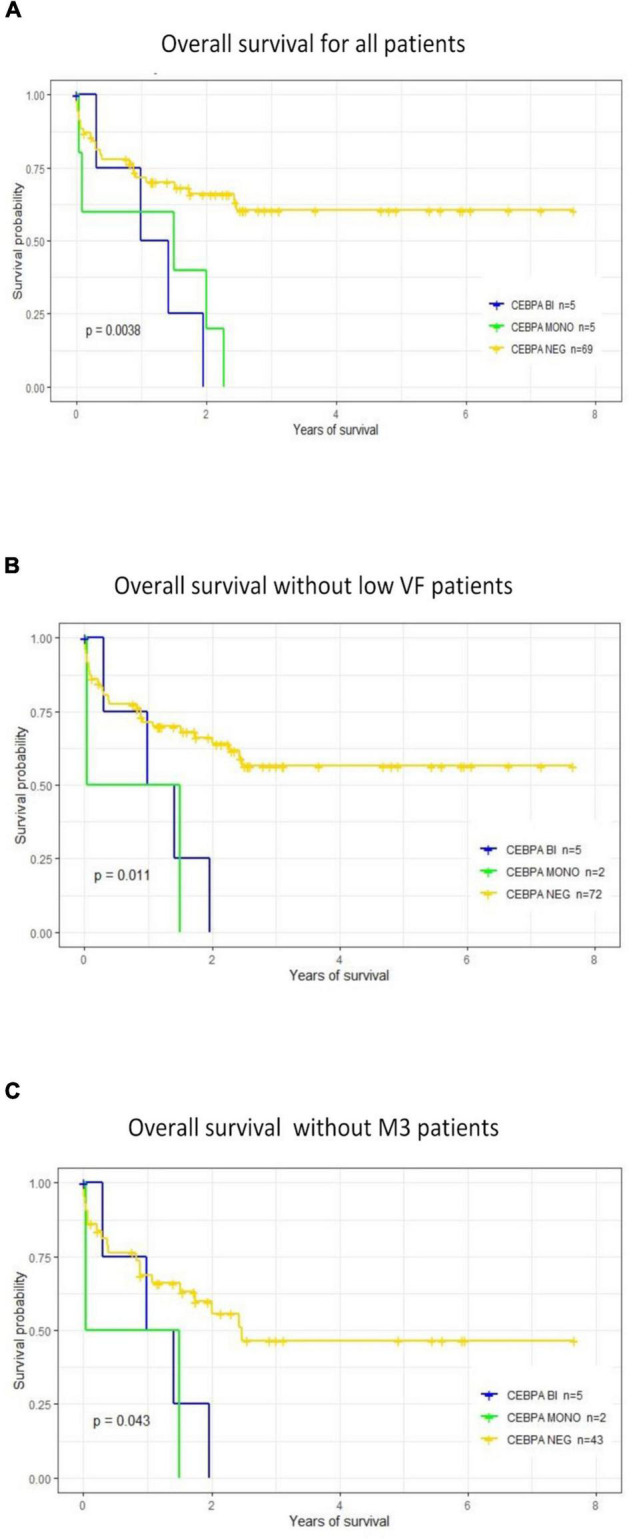

The impact of CEBPA mutation on OS was analyzed by comparing three subgroups of patients according to CEBPA status: CEBPAMONO (individuals with monoallelic mutations), CEBPABI, and CEBPANEG. The results are shown in Figures 2A–C. The OS significantly decreased in patients with CEBPA mutations compared with the CEBPANEG group (p = 0.002). No differences were found in OS between patients with CEBPAMONO and CEBPABI. Similar results were observed after removing from the analysis the three CEBPAMONO patients with CEBPA mutation VF < 2% (patients M157, M168, and M183). A significant decrease in OS was observed (p = 0.009), as shown in Figure 2B. OS analysis was performed after removing the M3 patients from the CEBPANEG mutated group. The result still showed a significantly lower OS in the CEBPAPOS group (p = 0.04; Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Prognostic impact of CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA) mutations on overall survival. (A) OS was analyzed considering the following groups: CEBPAMONO or CEBPABI vs. CEBPANEG. Groups with mono or biallelic mutations showed a significantly lower OS than patients without CEBPA mutations (CEBPANEG). (B) OS was analyzed after removing the three patients with CEBPAMONO and VF < 2%. Results are similar; OS is significantly lower in the CEBPA mutated subgroup. (C) Comparing OS between patients positive for CEBPA (CEBPABI or CEBPAMONO) vs. CEBPANEG, after removing patients classified as AML-M3. There is a significantly lower OS in the CEBPAPOS subgroups.

No statistically significant association was detected between CEBPAPOS cases and a low SES (p = 0.99) or between a low SES and a poor outcome (death) (p = 0.76; Results of the analysis are shown in Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the mutational landscape of the CEBPA gene and its clinical impact on Mexican patients with de novo AML. The proportion of CEBPAPOS patients was 12.5%, close to the 14.9% described in 315 AML pediatric patients (15) and the range of frequency reported in the adult population (7–16%) (15, 23). Of all identified mutations, 57.14% (8/14) were located at the N-terminus. Most of them were frameshifts predicted to result in the premature stop of the wild-type p42 translation while preserving the translation of a short p30 isoform by using the second ATG present downstream and overexpressing the p30 isoform (24). Mutation p.R142Sfs*18 is located downstream of the p30 start codon at the TAD2 domain and would suppress the expression of p42 and p30 isoform from this CEBPA mutated allele. Mutations in the C-terminus portion were less common, 28.57% (4/14), and were insertion/deletions that did not affect the gene reading frame. These mutations are distributed in both DNA binding and leucine zipper domains affecting the dimerization or the binding to the DNA processes (24).

A high proportion of the identified mutations are new; only 7 out of 14 had been previously reported in the COSMIC3 or dbSNP databases4 (as of March 2022). All the identified variants were uploaded to the ClinVar database. The high proportion of novel variants identified in this small subgroup of CEBPAPOS patients supports the importance of research focused on ethnically diverse populations of non-Caucasian ethnicities. A more comprehensive data on mutational profiles on cancer driver genes would contribute to a better understanding of the disparities in cancer outcomes observed by race/ethnicity (25).

All the novel mutations with VF > 40% were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to ACMG criteria (Supplementary Table 2). No functional in vitro analyses were performed to confirm their pathogenicity. However, most novel mutations are frameshift deletion (patients M173, M162, and M132) or inframe insertion (M160, M138, and M173). According to the COSMIC database statistics for CEBPA gene5, these types of mutations are the most frequent, representing 46% of all kinds of mutations in CEBPA across different tumors (Supplementary Figure 1). Considering this information and the published literature analyzing CEBPA mutations and their consequence, we thought it is improbable that these variants were not deleterious for the CEBPA protein functioning. The two variants with VF < 2% were classified as Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS); these variants were removed from the survival analysis.

Half of the CEBPAPOS patients had CEBPAMONO, similar to the findings in Japanese children with AML (55.5%) (15). The leukemogenic mechanism for monoallelic CEBPA is not clearly established. It has been proposed that monoallelic mutations favor a preleukemic stem cell that, through a multistep clonal evolutionary process, acquires additional cooperating mutations and fully develops a leukemic clone (26).

Pabst et al. described that around 60% of AML patients had biallelic mutated CEBPA (27). This proportion was lower in our series; CEBPABI mutations were found in 50% (5/10) of the cases. One patient was homozygous for a frameshift mutation affecting the TAD1 domain (M162). The other four were compound heterozygous for one variant located at the N-terminus and the other at the C-terminus region, the most common locations for biallelic mutations. Compound heterozygous and homozygous mutations have been previously identified in biallelic mutated CEBPA AML patients (15).

Biallelic mutation induces a biallelic expression of aberrant p30 isoforms; the residual p30 activity inhibits the remaining p42 protein in a dominant-negative manner and affects the myeloid differentiation process (27). Some data obtained in animal models propose that truncated p30 isoforms may also act as a gain of functions allele favoring the leukemogenesis. Knockout p42 mice with preserved p30 expression develop AML with complete penetrance; however, when both isoform expressions were abolished, AML was not developed (28, 29).

Germline CEBPA mutations induced a leukemia predisposition syndrome called familial CEBPA-mutated AML. They have been identified in 4–15% of CEBPAPOS AML (11, 30, 31). Germline mutations could be located at both the N- or C-terminus (11, 14, 32, 33), having a VF between 40 and 60% in heterozygous individuals. Mutations with VF close to the expected heterozygous value need further evaluation. DNA extracted from no hematopoietic tissue could be used to clarify its origin (34). In this study, patients with biallelic mutations showed VF close to the expected value for germline variant. However, no skin biopsy or remission samples were available for further evaluation. Although no AML family history was identified in the clinical records of our CEBPABI patients, germline origin cannot be confidently excluded based only on family history due to incomplete AML penetrance, incomplete family history, or the possibility of a de novo germline variant.

Impact of CEBPA Mutation on Clinical Features and Overall Survival

CEBPA mutations have been found more frequently among FAB M1 and M2 patients (35, 36). This was also true in our series (Table 2); M1 or M2 were present in 80% of the CEBPAPOS patients vs. 40% of the CEBPANEG subgroup (p = 0.01). However, a statistically significant difference was observed in the M2 distribution (p = 0.009). CEBPAPOS patients had a significantly higher WBC count at diagnosis; 50% of the CEBPAPOS patients had a WBC count > 100,000, compared with 12.9% in the CEBPANEG subgroup. Hyperleukocytosis at diagnosis has been associated with an increased risk for relapse in adults with CEBPABI AML (36). Due to the small number of patients in each subgroup, the statistical power is low to compare the distribution of clinical features between CEBPABI and CEBPAMONO.

CEBPA mutations were associated with a significantly lower OS but without significant differences between mono or biallelic CEBPA mutated patients. The mean OS in CEBPABI patients was 2 months longer than in CEBPAMONO (11.2 vs. 9.27 months p = NS).

Considering that the biological impact of mutations with VF < 2%, classified as VUS, that may belong to a small subclone, would be different from those present in a higher proportion in the dominant clone, we evaluated the effect of CEBPA mutations in OS after removing the three patients with low allelic fractions. The result was similar to the one obtained taking into account the whole CEBPAPOS group (Figure 2B).

Several studies have assessed the clinical impact of CEBPA biallelic mutations on the survival of pediatric patients to determine if they are useful biomarkers of favorable-risk AML, as observed in adults. The findings of the most representative studies are summarized in Table 3. In contrast with our results, none of those studies have reported a negative effect of CEBPA mutations on OS; they found no impact of CEBPA mutations or a positive effect mainly for CEBPABI mutations.

TABLE 3.

Results of different studies that evaluated the effect of CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Alpha (CEBPA) mutations in clinical outcomes of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients.

| Year of publication | Total patients | CEBPA POS | Clinical impact of CEBPA mutations | References |

| 2009 | 847 | 4.5% |

CEBPAPOS improved OS (at 5 years HR = 0.40, p = 0.023) and EFS (HR = 0.47, p = 0.01) No differences between CEBPABI and CEBPAMONO |

Ho et al. (47) |

| 2011 | 252 | 7.9% |

CEBPABI had significantly better OS as compared with CEBPAMONO and CEBPANEG CEBPABI was an independent marker for OS in multivariate analysis |

Hollink et al. (14) |

| 2011 | 170 | 6.0% | No impact on OS or EFS of CEBPA mutations | Staffas et al. (51) |

| 2014 | 315 | 14.9% |

CEBPAMONO and CEBPABI are independent favorable prognostic factors for EFS CEBPABI was an independent favorable prognostic factor for OS |

Matsuo et al. (15) |

| 2019 | 2958 | 5.4% | There were no differences in remission rates, OS, or EFS between CEBPAMONO and CEBPABI patients | Tarlock et al. (52) |

OS, overall survival; EFS, event-free survival.

Heterogeneity in relapse rates and survival outcomes has been reported in CEBPAPOS patients despite the favorable impact of CEBPABI mutations on OS (36). Concurrent mutations in other genes and a differential impact of CEBPA mutations according to their location would contribute to the observed heterogeneity (15, 37). We searched for concurrent mutations in FLT3, NPM1, CSF3R among CEBPAPOS patients; however, statistical tests could not be run due to the small sample size.

FLT3 was mutated with VF > 30% in 3 out of 10 CEBPAPOS patients (one CEBPABI and two CEBPAMONO). We had previously reported that FLT3 mutations have a negative impact on clinical outcomes in Mexican pediatric AML patients, and OS is significantly lower in patients with FLT3 mutations than in FLT3NEG (17, 37). Akin et al. reported that 2 out of 3 patients who carried concurrent CEBPA and FLT3 mutations died during treatment (38). A negative effect of FLT3 mutations on the CEBPABI positive effect has been observed in adult patients. However, a similar frequency of FLT3-ITD between mono and biallelic CEBPA mutated patients with no impact on OS has been found in children (14).

None of the CEBPAPOS patients harbored NPM1 mutations. This supports the idea that CEBPA and NPM1 mutations are mutually exclusive (39). The frequency of NPM1 in our series (1.2%) was much lower than previously reported (6–8%) (40–43).

CSF3R was mutated in two CEBPAPOS individuals; p.Thr618Ile with VF = 48.6% was identified in one of them. This activating mutation occurs in the membrane-proximal region of the colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor. The mutation produces ligand-independent receptor activation, a hallmark of chronic neutrophilic leukemia (44). Concurrent CSF3R mutations in pediatric CEBPABI AML were associated with significantly poorer relapse-free survival than wild-type CSF3R; however, OS was not significantly different (45). A similar impact of CSF3R mutations on CEBPABI groups has been reported in adults (46). A pathogenic mutation in WT1 with VF = 87% was also identified in one CEBPABI patient. Ho et al. also found three WT1-mutated patients in the CEBPABI subgroup, two of them died of progressive disease during induction (47). WT1 mutations are independent poor prognostic factors with a 5-year OS of 35% and EFS of 22% in children (48). No KIT mutations were identified in the CEBPAPOS patients.

In the present research, a low OS of the cohort was noted compared with reports of other parts of the world. It is well recognized that in developing countries, survival rates for this disease are low (∼40%). Several other biological and non-biological factors not evaluated in the present study could be contributing to this poor outcome. For instance, a late presentation, malnutrition, high treatment-related mortality, low SES, and high treatment abandonment rates have been recognized (49). The SES analysis performed, based on the mother years of study as an SES indicator, no statistically significant association was detected between CEBPAPOS positive cases and a low SES (p = 0.99) or between a low SES and a poor outcome (death) (p = 0.76; Results of the analysis are shown in Supplementary Table 1). SES does not seem to be a confounding factor affecting the results of this study.

This study has several limitations that must be considered to interpret the findings. Cytogenetic/FISH characterization is not routinely performed in most Mexican public institutions; it was not performed in these patients impairing the risk stratification and precluding further analysis aimed to evaluate the impact of CEBPA mutations on the normal karyotype subgroup. This study is a retrospective analysis of a heterogeneous group of patients treated according to four different protocols in eight different institutions. Although this study is the most extensive series of Mexican AML patients analyzed so far, the number of patients is small. Thus, it would reduce the statistical power to detect additional differences in the distribution of clinical features between positive and negative CEBPA patients.

However, these limitations do not seem to explain the significant reduction in OS in the CEBPAPOS. The lack of cytogenetic information at diagnosis and the use of different treatment regimens are common to the whole cohort of patients, not affecting the CEBPAPOS patients exclusively. The mutational status of CEBPA gene was unknown to the physician at the moment of choosing treatment protocols and during the whole course of the disease; therefore, a differential bias in clinical management affecting only the CEBPAPOS group is unlikely. CEBPAPOS patients were treated in 4 different hospitals. Therefore, a possible “hospital-effect” on OS of CEBPAPOS patients is also unlikely.

Conclusion

This study identifies the mutational landscape of the CEBPA gene in Mexican pediatric de novo AML patients and is the first to evaluate the impact on OS. The results suggest an adverse effect of CEBPA mutations in OS, compared with the good prognosis associated with CEBPA mutations in adults. Several molecular analyses support that pediatric and adult AML are different clinical and biological entities (50); therefore, the biomarkers identified in adults must be separately validated in the pediatric population before they can be confidently used for clinical management of the disease. Further prospective analyses of extensive series of well-characterized patients are needed to define the clinical impact of the CEBPA mutational status in pediatric de novo AML.

Nomenclature

Resource Identification Initiative

Cite this (ClinVar, RRID:SCR_006169)

URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/

Cite this(Genome Aggregation Database, RRID:SCR_01 4964)

URL: http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

Cite this (COSMIC - Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer, RRID:SCR_002260)

URL:http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/

Cite this (dbSNP, RRID:SCR_002338)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Genomic Medicine, Mexico City, Mexico, (document number 28-2015-1). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants or their legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

CM obtained the results, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. KC, LLF, MJ, AMu, and BV obtained and validated the results. HF validated the results and analyzed statistical data. JN, EJ, VB, JT, JF, JMa, MM, AMe, LE, JP, RE, LF, RA, MP, OS, HR, SJ, PG, and JMe collected clinical data and cared for patients. CA carried out the general supervision, the acquisition of funds, designed the study, obtained and validated the results, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients, their families, and the clinical personnel who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by CONACYT grants: “Fondo Sectorial de Investigación en Salud y Seguridad Social SS/IMSS/ISSSTE-CONACYT” number 000000000273210; FORDECYT- PRONACES 303082 and FORDECYT-PRONACES/303019/2019.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.899742/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:2209–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mejía Aranguré JM, Ortega Álvarez MC, Fajardo Gutiérrez A. Epidemiología de las leucemias agudas en niños. Parte 1. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. (2005) 43:323–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mejía-Aranguré JM, Núñez-Enríquez JC, Fajardo-Gutiérrez A, Rodríguez-Zepeda MDC, Martín-Trejo JA, Duarte-Rodríguez DA, et al. Epidemiología descriptiva de la leucemia mieloide aguda (LMA) en niños residentes de la Ciudad de México: reporte del grupo Mexicano interinstitucional para la identificación de las causas de la leucemia en niños. Gac Med Mex. (2016) 152(Suppl. 2):66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivera-Luna R, Cárdenas-Cardos R, Olaya-Vargas A, Shalkow-Klincovstein J, Pérez-García M, Alberto Pérez-González O, et al. El niño de población abierta con cáncer en México. Consideraciones epidemiológicas. An Med. (2015) 60:91–7. 17153703 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morais RVD, Souza MVD, Silva KADS, Santiago P, Lorenzoni MC, Lorea CF, et al. Epidemiological evaluation and survival of children with acute myeloid leukemia. J Pediatr (Rio J). (2021) 97:204–10. 10.1016/j.jped.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Ritter J, Reinhardt D, Hermann J, Henze G, et al. Treatment strategies and long-term results in paediatric patients treated in four consecutive AML-BFM trials. Leukemia. (2005) 19:2030–42. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilar-Hernandez M, Fernandez-Castillo G, Nunez-Villegas NN, Perez-Casillas RX, Nunez-Enriquez JC. Principales causas de mortalidad durante la fase de inducción a la remisión en los pacientes pediátricos con leucemia linfoblástica aguda. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. (2017) 55:286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Cancer Genome Atlas Rn. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:2059–74. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classi fi cation of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. (2016) 127:2391–406. 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Version 1.2022. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Wang F, Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang M, Liu H, et al. Companion gene mutations and their clinical significance in AML with double mutant CEBPA. Cancer Gene Ther. (2020) 27:599–606. 10.1038/s41417-019-0133-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green CL, Koo KK, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Linch DC, Gale RE. Prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in a large cohort of younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Impact of double CEBPA mutations and the interaction with FLT3 and NPM1 mutations. J Clin Oncol. (2010) 28:2739–47. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang DC, Shih LY, Huang CF, Hung IJ, Yang CP, Liu HC, et al. CEBPα mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. (2005) 19:410–4. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollink IHI, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Arentsen-Peters STCJ, Zimmermann M, Peeters JK, Valk PJ, et al. Characterization of CEBPA mutations and promoter hypermethylation in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. (2011) 96:384–92. 10.3324/haematol.2010.031336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuo H, Kajihara M, Tomizawa D, Watanabe T, Saito AM, Fujimoto J, et al. Prognostic implications of CEBPA mutations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Japanese pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group. Blood Cancer J. (2014) 4:e226–7. 10.1038/bcj.2014.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeshan K, Santilli G, Corradini F, Perrotti D, Calabretta B. Transcription activation function of C/EBPα is required for induction of granulocytic differentiation. Blood. (2003) 102:1267–75. 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina Garay C, Carrillo Sánchez K, Flores Lagunes LL, Jiménez Olivares M, Muñoz Rivas A, Villegas Torres BE, et al. Profiling FLT3 mutations in Mexican acute myeloid leukemia pediatric patients: impact on overall survival. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:586. 10.3389/fped.2020.00586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J ASA. (1958) 53:457–81. 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcotte EL, Thomopoulos TP, Infante-Rivard C, Clavel J, Petridou ET, Schüz J, et al. Caesarean delivery and risk of childhood leukaemia: a pooled analysis from the childhood leukemia international consortium (CLIC). Lancet Haematol. (2016) 3:e176–85. 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)00002-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petridou ET, Georgakis MK, Ma X, Heck JE, Erdmann F, Auvinen A, et al. Advanced parental age as risk factor for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results from studies of the childhood leukemia international consortium. Eur J Epidemiol. (2018) 33:965–76. 10.1007/s10654-018-0402-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards S, Nazneen A, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tawana K, Fitzgibbon J. CEBPA-associated familial acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, et al. editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; (2010). p. 1993–2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakral G, Vierkoetter K, Namiki S, Lawicki S, Fernandez X, Ige K, et al. AML multi-gene panel testing: a review and comparison of two gene panels. Pathol Res Pract. (2016) 212:372–80. 10.1016/j.prp.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiNardo CD. Getting a handle on hereditary CEBPA mutations. Blood. (2015) 126:1156–8. 10.1182/blood-2015-07-657908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, Carvajal-Carmona L, Coggins NB, Cruz-Correa MR, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. (2021) 124:315–32. 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somervaille TCP, Cleary ML. Mutant CEBPA: priming stem cells for myeloid leukemogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. (2009) 5:453–4. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pabst T, Mueller BU, Zhang P, Radomska HS, Narravula S, Schnittger S, et al. Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α (C/EBPα), in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. (2001) 27:263–70. 10.1038/85820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirstetter P, Schuster MB, Bereshchenko O, Moore S, Dvinge H, Kurz E, et al. Modeling of C/EBPα mutant acute myeloid leukemia reveals a common expression signature of committed myeloid leukemia-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. (2008) 13:299–310. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P, Iwasaki-Arai J, Iwasaki H, Fenyus ML, Dayaram T, Owens BM, et al. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell repopulating capacity and self-renewal in the absence of the transcription factor C/EBPα. Immunity. (2004) 21:853–63. 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tawana K, Wang J, Renneville A, Bödör C, Hills R, Loveday C, et al. Disease evolution and outcomes in familial AML with germline CEBPA mutations. Blood. (2015) 126:1214–23. 10.1182/blood-2015-05-647172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taskesen E, Bullinger L, Corbacioglu A, Sanders MA, Erpelinck CAJ, Wouters BJ, et al. Prognostic impact, concurrent genetic mutations, and gene expression features of AML with CEBPA mutations in a cohort of 1182 cytogenetically normal AML patients: Further evidence for CEBPA double mutant AML as a distinctive disease entity. Blood. (2011) 117:2469–75. 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pabst T, Eyholzer M, Haefliger S, Schardt J, Mueller BU. Somatic CEBPA mutations are a frequent second event in families with germline CEBPA mutations and familial acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:5088–93. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grossmann V, Haferlach C, Nadarajah N, Fasan A, Weissmann S, Roller A, et al. CEBPA double-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia harbours concomitant molecular mutations in 76.8% of cases with TET2 and GATA2 alterations impacting prognosis. Br J Haematol. (2013) 161:649–58. 10.1111/bjh.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiNardo CD, Routbort MJ, Bannon SA, Benton CB, Takahashi K, Kornblau SM, et al. Improving the detection of patients with inherited predispositions to hematologic malignancies using next-generation sequencing-based leukemia prognostication panels. Cancer. (2018) 124:2704–13. 10.1002/cncr.31331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fasan A, Haferlach C, Alpermann T, Jeromin S, Grossmann V, Eder C, et al. The role of different genetic subtypes of CEBPA mutated AML. Leukemia. (2014) 28:794–803. 10.1038/leu.2013.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn JS, Kim JY, Kim HJ, Kim YK, Lee SS, Jung SH, et al. Normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia patients with CEBPA double mutation have a favorable prognosis but no survival benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplant. Ann Hematol. (2016) 95:301–10. 10.1007/s00277-015-2540-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendoza H, Podoltsev NA, Siddon AJ. Laboratory evaluation and prognostication among adults and children with CEBPA-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. (2021) 43(Suppl. 1):86–95. 10.1111/ijlh.13517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akin D, Oner D, Kurekci E, Akar N. Determination of CEBPA mutations by next generation sequencing in pediatric acute leukemia. Bratisl Med. (2018) 119:366–72. 10.4149/BLL_2018_068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin LI, Lin TC, Chou WC, Tang JL, Lin DT, Tien HF. A novel fluorescence-based multiplex PCR assay for rapid simultaneous detection of CEBPA mutations and NPM mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemias. Leukemia. (2006) 20:1899–903. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown P, McIntyre E, Rau R, Meshinchi S, Lacayo N, Dahl G, et al. The incidence and clinical significance of nucleophosmin mutations in childhood AML. Blood. (2007) 110:979–85. 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cazzaniga G, Dell’Oro MG, Mecucci C, Giarin E, Masetti R, Rossi V, et al. Nucleophosmin mutations in childhood acute myelogenous leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. (2005) 106:1419–22. 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braoudaki M, Papathanassiou C, Katsibardi K, Tourkadoni N, Karamolegou K, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F. The frequency of NPM1 mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. (2010) 3:41. 10.1186/1756-8722-3-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balgobind BV, Hollink IHIM, Arentsen-Peters STCJM, Zimmermann M, Harbott J, Berna Beverloo H, et al. Integrative analysis of type-I and type-II aberrations underscores the genetic heterogeneity of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. (2011) 96:1478–87. 10.3324/haematol.2010.038976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price A, Druhan LJ, Lance A, Clark G, Vestal CG, Zhang Q, et al. T618I CSF3R mutations in chronic neutrophilic leukemia induce oncogenic signals through aberrant trafficking and constitutive phosphorylation of the O-glycosylated receptor form. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2020) 523:208–13. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarlock K, Alonzo T, Wang YC, Gerbing RB, Ries RE, Hylkema T, et al. Prognostic impact of CSF3R mutations in favorable risk childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. (2020) 135:1603–6. 10.1182/blood.2019004179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su L, Gao SJ, Tan YH, Lin H, Liu XL, Liu SS, et al. CSF3R mutations were associated with an unfavorable prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia with CEBPA double mutations. Ann Hematol. (2019) 98:1641–6. 10.1007/s00277-019-03699-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho PA, Zeng R, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Miller KL, Pollard JA, et al. Prevalence and prognostic implications of CEBPA mutations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a report from the children’s oncology group. Blood. (2010) 116:702–10. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollink IHIM, Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Zimmermann M, Balgobind BV, Arentsen-Peters STCJM, Alders M, et al. Clinical relevance of Wilms tumor 1 gene mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. (2009) 113:5951–60. 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghafoor T, Khalil S, Farah T, Ahmed S, Sharif I. Prognostic factors in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Experience from A Developing Country. Cancer Rep. (2020) 3:e1259. 10.1002/cnr2.1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conneely SE, Rau RE. The genomics of acute myeloid leukemia in children. Cancer Metastasis Rev. (2020) 39:189–209. 10.1007/s10555-020-09846-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staffas A, Kanduri M, Hovland R, Rosenquist R, Ommen HB, Abrahamsson J, et al. Presence of FLT3-ITD and high BAALC expression are independent prognostic markers in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. (2011) 118:5905–13. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-353185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarlock K, Alonzo TA, Wang Y-C, Gerbing RB, Ries RE, Hylkema TA, et al. Somatic Bzip Mutations of CEBPA Are Associated with Favorable Outcome Regardless of Presence As Single Vs. Double Mutation. Blood. (2019) 134(Suppl. 1):181–181. 10.1182/blood-2019-126273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.