Abstract

Upon replacement of molybdenum by tungsten in DMSO reductase isolated from the Rhodobacteraceae family, the derived enzyme catalyzes DMSO reduction faster. To better understand this behavior, we synthesized two tungsten(VI) dioxido complexes [WVIO2L2] with pyridine- (PyS) and pyrimidine-2-thiolate (PymS) ligands, isostructural to analogous molybdenum complexes we reported recently. Higher oxygen atom transfer (OAT) catalytic activity was observed with [WO2(PyS)2] compared to the Mo species, independent of whether PMe3 or PPh3 was used as the oxygen acceptor. [WVIO2L2] complexes undergo reduction with an excess of PMe3, yielding the tungsten(IV) oxido species [WOL2(PMe3)2], while with PPh3, no reactions are observed. Although OAT reactions from DMSO to phosphines are known for tungsten complexes, [WOL2(PMe3)2] are the first fully characterized phosphine-stabilized intermediates. By following the reaction of these reduced species with excess DMSO via UV–vis spectroscopy, we observed that tungsten compounds directly react to WVIO2 complexes while the Mo analogues first form μ-oxo Mo(V) dimers [Mo2O3L4]. Density functional theory calculations confirm that the oxygen atom abstraction from WVIO2 is an endergonic process contrasting the respective reaction with molybdenum. Here, we suggest that depending on the sacrificial oxygen acceptor, the tungsten complex may participate in catalysis either via a redox reaction or as an electrophile.

Short abstract

A W(VI) dioxido complex with pyridine-2-thiolate ligands mimics the activity of DMSO reductase. The W complex catalyzes the reactions more efficiently than the Mo analogue, similar to the catalytic behavior of DMSO reductase upon metal ion replacement. Surprisingly, the catalytic performance was higher for PPh3 than for PMe3, suggesting two different mechanisms. While with PMe3, reduction to a W(IV) species is observed, with PPh3, the W(VI) complex seems to play the role of an electrophile.

Introduction

Nature has taken advantage of minor differences in the coordination chemistry of molybdenum and tungsten to perform several sophisticated enzymatic transformations. The physicochemical properties of their bioavailable (oxo)anions, MO42– (M = Mo, W), allow similar odds for both metals to incorporate into the enzyme structure. Generally, in tungsto- and molybdoenzymes, the metal center in oxidation state +IV or +VI is coordinated by one or two of any variations of the metallopterin moiety.1,2 However, the activity of the metalloenzymes is strongly dependent on the metal ion situated in their active site.3,4 Some molybdoenzymes, such as sulfite oxidase5 or nitrate reductase,6−8 are less active or not active at all upon replacement of Mo by W. Conversely, when molybdenum is replaced with tungsten in DMSO reductase (DMSOr) from Rhodobacter capsulatus or Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the derived enzyme reduces DMSO at a higher rate but also is inactive in catalyzing the reverse DMS oxidation.9,10 Similarly, trimethylamine−N–oxide reductase (TMAOr) from Escherichia coli shows a slight increase in catalytic activity when molybdenum is substituted by tungsten.11 Both DMSOr and TMAOr catalyze biochemical transformations known as oxygen atom transfer (OAT) which are widespread reactions for molybdenum and tungsten oxidoreductase enzymes.12,13 To better understand the mechanism under which the metalloenzymes perform the OAT, many molybdenum model compounds were synthesized and investigated, while tungsten modeling chemistry is far less explored.1,14,15 Frequently used model reactions for OAT usually employ the biological substrate DMSO and different tertiary phosphines as sacrificial oxygen acceptors.16−18 In general, if the catalyst is based on a higher-valent metal center (MVIO22+), OAT model reactions involve the concomitant two-electron reduction coupled with oxygen abstraction by the oxygen acceptor (Scheme 1a).16 Reduced species (MIVO2+) can further undergo oxidation to recover the catalyst by abstracting the oxygen from DMSO or any related substrate (Scheme 1b).19

Scheme 1. Reaction Steps in an OAT Using Model Complexes.

Enzyme-like reactivity was achieved with different model catalysts, most frequently dithiolene-based molybdenum complexes due to their resemblance to the biological active sites.20−22 However, there are still many limitations to overcome since dithiolene-based ligands often cause the formation of tris chelate compounds with molybdenum and tungsten in oxidation states +IV or +V.1 Another issue in OAT modeling chemistry with molybdenum is the formation of relatively inert Mo(V) μ-oxo dimers, which are formed upon comproportionation of a Mo(IV) and Mo(VI) species (Scheme 1c).4,14 These dimers may still support OAT reactions but often decrease the catalytic performance depending on the position of the equilibrium. While special care must be taken for the analysis of the equilibrium,23 it may be regulated by the ligands’ steric and electronic properties.24,25 Thus, the dinuclear Mo(V) species may be viewed as an “electronic buffer,” where the two electrons are each localized on a single molybdenum center.23

Tungsten(VI) models in OAT reactions are studied less and mainly alongside analogous molybdenum compounds. Such investigations revealed that analogous Mo(IV, VI) and W(IV, VI) complexes are nearly isostructural;4 however, lower or no catalytic activity of the tungsten system is usually observed.26−28 This may mainly be explained by the half-reaction of the catalytic cycle requiring reduction of the metal center (Scheme 1a), which is often challenging with tungsten due to its lower redox potential.29−31 Possibly for these reasons, W(V) μ-oxo dimers are only known with scorpionate32,33 and dithiocarbamate ligands,34,35 besides an organometallic example.36 Comparative studies revealing a higher OAT activity of the tungsten(VI) compound than that of the molybdenum analogue are extremely rare. Some years ago, we described Mo(VI) and W(VI) complexes with a [ONN] donor, which catalyzed the OAT from DMSO to PMe3, and found the higher homolog to be significantly more efficient.37 However, reduction of the tungsten(VI) center was not observed even with an excess of phosphine, which made us consider retention of the oxidation state throughout the catalytic cycle. For this reason, additional studies should be carried out with tungsten(VI) compounds. Furthermore, they are generally more stable at elevated temperatures and show lower affinity toward μ-oxo dimers formation.

We recently described functional DMSO reductase models of the type [MoO2L2] with bidentate monoanionic pyridine/pyrimidine-2-thiolate ligands. Those complexes react with PMe3 and PPh3, yielding Mo(IV) and Mo(V) species, respectively.38 Here, we present the challenges and results of replacing the molybdenum with tungsten in analogous complexes.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of Tungsten (VI) Dioxido Complexes

Two tungsten(VI) dioxido complexes [WO2L2] (L = pyridine-2-thiolate (PyS), (1) and pyrimidine-2-thiolate (PymS), (2)) were synthesized in two steps starting from the tungsten(II) precursor [WBr2(CO)3(MeCN)2] (Scheme 2). After reacting the precursor with 2.05 equiv of the ligand salt NaL in CH2Cl2 to obtain related tricarbonyl complexes [W(CO)3L2], the reaction mixture was filtered and reacted with two equiv of pyridine-N-oxide overnight. After concentrating the solution and adding MeCN, dark yellow microcrystals of the products were collected in good yields directly from the reaction flask upon cooling or slow solvent removal.

Scheme 2. Two-Step Synthesis of [WO2L2] Complexes.

Alternatively, synthesis of [WO2L2] could also be performed starting from tungsten(VI) precursors [WO2Cl2(dme)] (dme = dimethoxyethane) and [WO2(acac)2] (acac = acetylacetonate) at −10 °C via salt metathesis or ligand substitution, but many impurities complicate the work-up. For the synthesis of 2, inert conditions are crucial because otherwise almost immediate ligand hydrolysis occurred accompanied by the formation of the tungsten(IV) species [W(PymS)4] (together with the disulfide of the ligand).39

Complex 1 is soluble, while complex 2 has low solubility in chlorinated solvents. Low solubility in MeCN and hydrocarbons was observed for both complexes. Although stable in solid-state for a few days under ambient conditions, solutions of 1 and 2 are sensitive to moisture, and syntheses were successful only under strictly inert conditions. The dioxido complexes were nevertheless isolated in pure form and fully characterized. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy revealed the existence of only one isomer in solutions of 1 and 2 and, together with elemental analysis, confirmed the purity of the samples. IR signals deriving from W=O bonds were detected in a range of 902–953 cm–1, similar to other neutral WVIO2 complexes.40−42 Compounds 1 and 2 were crystallized from CH2Cl2/MeCN at −37 °C to obtain a single crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. Experimental details and structure refinements are reported within the Supporting Information. Molecular views are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures (50% probability thermal ellipsoids) of complexes 1 (left) and 2 (right) showing the atomic numbering scheme. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Both WVIO2 complexes crystallized as single isomers with sulfur atoms oriented trans and nitrogen atoms cis to each other and trans to oxygen atoms. The structures are isotypic with the published molybdenum analogues,38,43,44 with metal–oxygen double bonds slightly elongated for the tungsten analogues (W–O bonds range: 1.715–1.743 Å; Mo–O bonds range: 1.693–1.711 Å), as previously observed in the literature.45 This is certainly due to the differences in the radial distribution functions of the Mo and W orbitals involved in the bonding. Single crystals of compound 2 reveal two conformers, where the angle between the two least–square planes of the two ligands varies [71.1(5) and 75.4(5)°].

W versus Mo in OAT Catalysis

To test the catalytic activity of complexes 1 and 2, identical experimental conditions were used as in our previous molybdenum OAT work allowing direct comparison.38 Accordingly, well-dried deuterated DMSO was used as an oxygen donor and solvent, while PMe3 or PPh3 were used as oxygen acceptors. To remove all solvent residues, complexes were dried in vacuo at 50 °C for at least 5 h before use. Catalyst loading was 1 mol % calculated versus phosphines used as limiting reagents. The formation of the respective phosphine oxides was followed via 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy at rt, and all the samples were prepared in J. Young NMR tubes to provide a water- and air-free environment. Blank experiments revealed that complex 2 is not stable in the DMSO-d6 solution because of decomposition to the disulfide (PymS)2 (1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): 8.71 (d, 4H), 7.37 (t, 3H)), DMS-d6 and presumably WO3. The formation of (PymS)2 was confirmed by independent synthesis as described in the Supporting Information.46 Furthermore, a 1H NMR spectrum of a CDCl3 solution of 2 with an excess of DMSO revealed signals in the region 1.85–2.07 ppm for DMS. Nevertheless, a comparison between tungsten and molybdenum catalysts was possible for the pyridine-2-thiolate system [MO2(PyS)2] (M = Mo or W), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of Catalytic OAT Reactions between DMSO and PPh3 and PMe3a.

| catalytic loading and catalyst | conversion (%) | time |

|---|---|---|

| PMe3 → OPMe3 | ||

| 1 mol % [MoO2(PyS)2] | 100 | >2 weeks |

| 1 mol % [WO2(PyS)2] | 100 | 5 h |

| PPh3 → OPPh3 | ||

| 1 mol % [MoO2(PyS)2] | 100 | 48 h |

| 1 mol % [WO2(PyS)2] | 100 | 3.5 h |

Conditions: DMSO-d6 (0.5 mL), PPh3 (114 μmol) or PMe3 (233 μmol), and catalyst (1 mol % vs PPh3 or PMe3). Full conversion of PPh3 to OPPh3 and PMe3 to OPMe3, respectively, was determined by NMR spectroscopy. All experiments were performed at least three times. In blank experiments without a metal complex, no conversion of phosphines was observed.

As summarized in Table 1, OAT experiments reveal significantly higher activity of the tungsten compound, both with PMe3 and PPh3, respectively, compared to molybdenum. Surprisingly, the more basic PMe3 was less efficiently converted than PPh3, suggesting different mechanisms between the two substrates. The higher activity of the tungsten compound is unexpected since, in most comparative literature studies, tungsten complexes were either less efficient or not active at all.17,26,27,41,47 Indeed, if considering a typical OAT mechanism,13 which includes the reduction of a metal center M(VI) to M(IV), molybdenum catalysts are expected to be faster due to their favorable redox potentials.31 In the tungsten-catalyzed experiment with PMe3, the yellow color of the DMSO solution of 1 changed initially to dark green, indicating that the mechanism occurs via reduction, identical to the suggested molybdenum-based pathway. On the other hand, no color change was observed during the tungsten-catalyzed experiments with PPh3. To further elucidate this unusual behavior in catalysis, the reactivity of complexes 1 and 2 toward phosphines was investigated in absence of DMSO.

Reactivity of [WO2L2] toward Phosphines

Although [MoO2L2] complexes react with PPh3 yielding μ-oxo dimers [Mo2O3L4],38 tungsten complexes 1 and 2 do not react with PPh3 under the same conditions. Also, with longer reaction times (24 h) and the use of various solvents (CD2Cl2, MeCN-d3, and C6D6), no OPPh3 was observed, as evidenced by 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy. On the other hand, both complexes react with 3 equiv of the more electron-rich phosphine PMe3 overnight (Scheme 3) under the formation of the seven-coordinated reduction products [WO(PMe3)2L2] (L = PyS 3, PymS 4) and OPMe3. They can be isolated in good yields after work-up as described in the Supporting Information as dark green (3) or violet (4) microcrystals. Both compounds contain two PMe3 ligands in trans position to each other. Such a stabilization, which is not possible with PPh3 due to steric hindrance, allows the reduction of the metal center with the sterically less demanding PMe3. Tungsten(IV) oxido compounds with two trans phosphine ligands that are obtained via OAT from tungsten(VI) dioxido complexes have as yet not been described.

Scheme 3. Reduction of [WO2L2] with PMe3 in Chlorinated Solvents at rt.

However, two trans-oriented phosphines stabilizing a d2 W center were observed in [WO(PMe2Ph)2L] (L = 2,2′:6′,2″:6″,2‴-quaterpyridine)48 and [W(O)Cl2(CO)(PMePh2)2],49 but they were not studied in the context of OAT. The monophosphine complex [WO(S2CN(CH2Ph)2)2(PMe3)] was also described, but structural data is lacking.35 None of the mentioned examples were prepared by synthetic routes, including the reduction of a tungsten(VI) species.

Compounds 3 and 4 are very well soluble in chlorinated hydrocarbons, MeCN, and THF and poorly soluble in hydrocarbons and diethyl ether. The complexes are stable in chloroform for several days, unlike the molybdenum variants.

IR spectroscopy revealed a strong band at 940 cm–1 for both 3 and 4, indicating the existence of a W≡O bond, which is following molybdenum analogues38 and related W(IV) species.50 To obtain meaningful NMR data for complex 4, it was necessary to perform variable-temperature NMR experiments due to dynamic behavior (Figure 2). At room temperature, two broad signals and one sharp triplet appear in the aromatic region. At −30 °C, free rotation of the coordinated pyrimidine-2-thiolate ligand about its C2 axis is hindered, revealing sharp signals for all aromatic protons. The rotation is possible since the W–N bond is rather weak, which is consistent with the observed lower stability of the pyrimidine system in DMSO. Furthermore, decoordination is feasible in the presence of a π–donor oxido ligand.

Figure 2.

VT 1H NMR spectra of 4 in CDCl3 (measured at rt, 10, 0, −10, −20, −30 °C). The scheme represents the rotation about the C2 axis within the coordinated ligand. The second ligand was omitted for better visualization.

1H NMR spectra show that 3–4 exist as single isomers in solution. Owing to virtual coupling, protons belonging to two trans-coordinated PMe3 appear as virtual triplets resonating at ≈1.36 ppm and integrating for 18H. Also, carbons belonging to coordinated PMe3 show triplets in the 13C NMR spectra. [MOL2(PMe3)2] (M = Mo, W; L = PyS, PymS) are isotypic for both metals allowing comparison of NMR data (Table 2).

Table 2. Chemical Shifts (ppm) of H and P Atoms in the Analogous WIV and MoIV Complexesa.

| δ (ppm)a | 1H (PyS/PymS) | 1H (PMe3) | 31P{1H} | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [WO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] (3) | 8.68, 6.87, 6.69, 6.49 | 1.33 | –27.51 | |

| [MoO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] | 8.73, 7.16, 6.63, 6.56 | 1.24 | –8.07 | (38) |

| [WO(PymS)2(PMe3)2] (4) | 8.73, 7.89, 6.74 | 1.34 | –27.66 | |

| [MoO(PymS)2(PMe3)2] | 8.56 (4H), 6.66 | 1.25 | –9.00 | (38) |

NMR spectra were recorded in CD2Cl2 and at rt.

The effect of metal ion replacement is observable upon a comparison of the 31P{1H} NMR spectra: signals belonging to PMe3 coordinated to Mo are downfield shifted by approx. 20 ppm due to the lower π basicity of the metal. Furthermore, signals of the tungsten compounds 3 and 4 reveal 183W satellites, which are absent in the Mo complexes.38

Compound 3 crystallized from a CH2Cl2/n-heptane mixture at −37 °C, while compound 4 crystallized from a saturated MeCN solution, forming single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. Molecular views are presented in Figure 3, and selected bond lengths and angles are shown in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Molecular structures (50% probability thermal ellipsoids) of complexes 3 (left) and 4 (right) showing the atomic numbering scheme. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 3. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) of [MIVOL2(PMe3)2] (M = W, Mo; L = PyS (3); PymS (4)).

| 3 | 4a | [MoO(PyS)2(PMe3)2]38 | [MoO(PymS)2(PMe3)2]38 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M–O | 1.745(2) | 1.727(3) | 1.7190(11) | 1.7115(13) |

| M–S1 | 2.6675(8) | 2.6825(13) | 2.6906(4) | 2.6880(5) |

| M–S2 | 2.6668(10) | 2.6399(12) | 2.6891(4) | 2.7006(5) |

| M–N11 | 2.205(3) | 2.162(4) | 2.2228(13) | 2.2084(17) |

| M–N21 | 2.195(3) | 2.181(4) | 2.2234(13) | 2.2072(16) |

| M–P1 | 2.4760(8) | 2.4909(14) | 2.4910(4) | 2.5023(5) |

| M–P2 | 2.4883(9) | 2.4936(14) | 2.4994(4) | 2.5080(6) |

| P1–M1–P2 | 170.08(3) | 170.96(4) | 168.946(14) | 169.654(19) |

The crystal structure analysis of 3 and 4 revealed a pentagonal bipyramidal surrounding of the W atom with two PMe3 ligands trans to each other, confirming 1H NMR data. The asymmetric unit of 4 consists of two complexes (4a and 4b) with the same connectivity and slightly different geometrical parameters. Here, only data of 4a are discussed, while those of 4b are given in the Supporting Information (Table S6).

Compounds 3 and 4 are isostructural to previously described molybdenum versions.38 As expected, the M=O bonds are slightly longer in the higher homolog. Moreover, all listed complexes have rather large M–S distances compared to previously described complexes with pyridine and pyrimidine-2-thiolate ligands,51,52 which is presumably due to the higher coordination number. However, the metal–sulfur distances are shorter than in reported Mo/W complexes with thioether ligands.42,45,53

Mechanistic Insights into OAT Catalysis with PMe3

The proposed cycle for [MoO2L2]-catalyzed OAT suggests three steps: (1) reduction of the starting compound with 3 equiv of PMe3 to stable 18e– species [MoOL2(PMe3)2], (2) reversible dissociation of two trans-coordinated PMe3 to form catalytically active [MoOL2], and (3) reoxidation to the starting [MoO2L2] with DMSO and formation of DMS.38 The first step is favorable for Mo compounds since the redox potential of Mo(VI)/Mo(IV) is usually higher than for W(VI)/W(IV).29 Moreover, the time necessary to reduce MVIO2 to [MOL2(PMe3)2] (M = Mo or W) with PMe3 is shorter for the Mo variants (3 h for Mo vs 16 h for W), evidenced by comparing synthetic procedures (see the Supporting Information and previous publication38). Here, we followed the oxidation step via UV–vis spectroscopy. Excess DMSO (1000 equiv) was added to a CH2Cl2 solution of the respective [MO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] complex at room temperature, and data were acquired until complete conversion (Table 4).

Table 4. Reaction Time for the Oxidation of [MO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] with 1000 equiv of DMSO to [MO2(PyS)2]a.

| compound | reaction completed after (h) |

|---|---|

| [MoO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] | 9 |

| [WO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] (3) | 5 |

Conditions: to a 3 mL of CH2Cl2 solution of the [MO(PMe3)2(PyS)2] (0.3 μmol) in a quartz cuvette, 1000 equiv of DMSO was added in the glove box. UV–vis measurement started 3 min after the preparation of the sample. The screening was performed at 25 °C.

As expected, reoxidation of W(IV) to W(VI) with DMSO is faster by a factor of 1.8 compared to Mo, which is similar to the oxidation rate differences observed for dithiolene-based MIVO complexes.54 However, a detailed analysis of the UV–vis spectra reveals significant differences between the two metals (Figure 4). Namely, the MoIVO complex does not simply react to the respective MoVIO2, but an intermediate species is formed after 1.5 h of reaction (Figure 4a). This species with λmax values at 370 and 505 nm we found to be the dinuclear molybdenum(V) compound [Mo2O3(PyS)4], previously reported as a product of the reduction of MoVIO2 with PPh3.38 Such dimers are common in molybdenum oxido chemistry.55−57 Here, it further reacts slowly with an excess of DMSO, yielding the oxidized MoVIO2 complex (Figure 4b). [Mo2O3(PyS)4] is poorly soluble in any solvent, precluding NMR spectroscopic observation. To confirm that the dimer is formed before the conversion to the dioxido complex, [MoO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] was reacted with 1 or 2 equiv of DMSO in CD2Cl2 in a J. Young tube, which caused crystallization of [Mo2O3(PyS)4] in pure form in both cases.1H NMR spectra of the solution revealed the formation of DMS and OPMe3, while no traces of the dioxido complex were observed. Dimer formation gives evidence that the short-living species [MoOL2] is indeed formed in the solution, which immediately reacts with [MoO2L2]. Thus, the dimer may be considered a resting state of the catalytic cycle. The oxidation rate of the molybdenum dimer is quite low (Figure 4b,c), which is influenced by the dissociation barrier38 and the low solubility.

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis spectra of the reaction of [MoO(PyS)2(PMe3)2] (λ1max = 360 nm; λ2max = 435 nm) to [Mo2O3(PyS)4] (λ1max = 370 nm; λ2max = 505 nm) during the first 1.5 h; (b) UV–vis spectra of the reaction of [Mo2O3(PyS)4] with DMSO forming [MoO2(PyS)2] (λmax = 385 nm) during the following 7.5 h; (c) absorbance at 505 nm over 9 h; (d) UV–vis spectra at the beginning (blue), after 1.5 h (red), and after 9 h (green) of the reaction.

In contrast, the formation of a dimer was not observed by UV–vis spectroscopy when reacting tungsten compound 3 with an excess of DMSO (Figure S17), but rather the oxidized tungsten(VI) complex [WO2(PyS)2] is formed directly. In the reaction of 3 with DMSO, one PMe3 may dissociate first, leaving a vacant site for DMSO to interact with the complex and transfer an oxygen atom, causing the second PMe3 to leave. Thus, phosphine-free [WOL2] is presumably never formed, so W dimer formation is not observed in contrast to molybdenum. Additionally, tungsten dimer formation might not be possible here because WVIO2 is not a good enough oxidant for WIVO due to unfavorable differences in redox potentials of the WVI/WV and WV/WIV couples. However, the flexibility of the [MOL2] core with bidentate ligands (L = PyS, PymS) allows the isolation of the reduced product. In this case, the angle between the two least–square planes of the ligands in [MO2L2] expands from 71.1(5)° (L = PymS) or 80.33(15)° (L = PyS) to an almost coplanar geometry in [MOL2(PMe3)2]. We assume that the stabilization by two trans PMe3 molecules is crucial for the isolation of reduced species and that, therefore, a lack of flexibility in other ligand systems prevents the formation of phosphine-stabilized OAT intermediates for tungsten. Such a rearrangement seems unlikely in the enzymes where the two metalloprotein ligands are locked into a pseudo-cis orientation by a plethora of hydrogen bonds.58−61

Suggested OAT Mechanism with PPh3

As described above, dioxido compounds 1 and 2 do not react with PPh3 while nevertheless catalyzing OAT with DMSO. For this reason, an alternative mechanism with PPh3 versus PMe3 seems likely. Since no reduction of the tungsten center was observed during catalysis, the mechanism presented in Scheme 4 is suggested. Accordingly, the tungsten center enables polarization of the DMSO molecule under the formation of a 7-coordinate intermediate stabilized by delocalization of the charge over two W–O double bonds. The electrophilic metal center renders the oxygen atom at DMSO prone to a nucleophilic attack by phosphine. Upon elimination of phosphine oxide, the catalyst is recovered. The suggested cycle avoids the reduction of the third-row metal tungsten. We have previously observed such behavior where tungsten(VI) dioxido compounds were not reduced by PMe3 but still catalyzed OAT.37

Scheme 4. Proposed OAT Mechanism Catalyzed by Complex 1.

With the second-row metal molybdenum reduction with PPh3 is possible, so the mechanism via the μ-oxo dimer analogous to the one with PMe3 is favored.

A mechanism for the W-catalyzed PPh3 oxidation with DMSO via the reduction of the tungsten center could, in principle, be envisioned via a transient [WOL2] species which is too short-lived to detect and also to form the dimer. However, our NMR experiments (vide supra) revealed no traces of reduction in the absence of an oxygen donor, and our calculations (vide infra) reveal high energy for obtaining [WOL2], arguing against such a mechanism.

The suggestion that OAT with W enzymes might not proceed via reduction and oxidation of the metal is intriguing and should be compared with the discussed mechanism of tungsten-dependent acetylene hydratase (AH).2 The latter, exhibiting a similar active site as the OAT enzymes, catalyzes the hydration of acetylene, a nonredox reaction. The tungsten center is proposed to remain in the oxidation state +IV throughout the catalytic cycle. This suggests that W may act as an electrophile, both in AH and certain OAT enzymes. Owing to size restrictions in the active site of DMSO reductase, the substrate could be polarized and further reduced without formation of an intermediate 7-coordinate species.

Theoretical Calculations

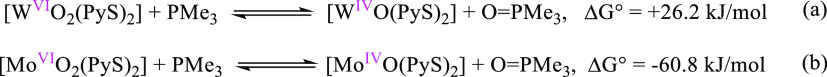

To better understand the general reluctance of tungsten oxido complexes to form the μ-oxo dimeric species, ΔG° values for the abstraction of one oxygen atom by a phosphine molecule were determined by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. To simplify the computation, PMe3 was considered as an oxygen acceptor instead of the larger PPh3. Calculated Gibbs free energies are given in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Gibbs Free Energies for the Abstraction of One Oxygen Atom from the Respective Dioxido Complexes by PMe3.

ΔG° values reveal that the oxygen atom abstraction from the tungsten compound is an endergonic process. In contrast, the negative value in the case of molybdenum indirectly supports the fact that dimers are formed effortlessly. Results reveal that the WIVO complex is a high-energy species and that even the easy formation of O=PMe3 does not deliver enough energy to compensate. However, the coordination of two molecules of PMe3 seems to stabilize the coordination core, as we were able to isolate compounds of the type [WOL2(PMe3)2]. We also calculated the ΔG° values for the formation of dimers from corresponding MIVO and MVIO2 compounds (Scheme 6). While the molybdenum dimer [Mo2O3(PyS)4] is an isolated species, calculations with the analogous tungsten dimer [W2O3(PyS)4] are virtual.

Scheme 6. Gibbs Free Energies for the Formation of Virtual WV and the Isolated MoV Dimer.

These results reveal that if [WO(PyS)2] exists in solution, dimerization should occur easily, suggesting that the phosphine-free W(IV) species is never formed. This also supports the suggestion that during the oxidation of [WOL2(PMe3)2], first, one phosphine is detached, and the second one dissociates only after the monophosphine species [WOL2(PMe3)] interacts with DMSO. We assume that the [WOL2(PMe3)] is not a powerful enough reductant to reduce the dioxido complex and form the dimer. Moreover, the stability of [WO2(PyS)2] might be additionally enhanced by the sulfur ligands. Indeed, the average M–S bonds are shorter for the monomers than for the dimers.38,62,63 Other comparative studies with Mo and W compounds reach similar conclusions. For example, [MO2Cl2(mbipy)] (M = Mo, W; mbipy: 5,5′-dimethyl-2,2′-dipyridyl) reacts with 2 equiv of thiophenol in basic conditions to form [WO2(SPh)2(mbipy)] or [Mo2O2(μ-O)2(SPh)2(mbipy)2], wherein the latter case reduction to MoV is observed under formation of disulfide.62 Since dimerization, in this case, includes M–S bond formation and breaking, the authors suggest that the tungsten compound resists reduction and dimerization due to the high stability of W–S bonds.

All this suggests that the higher activity of the tungsten catalyst derives from the reluctance of dimerization or, in other words, the lower activity of molybdenum derives from the ease of dimerization, hindering further reactivity.

Conclusions

Biomimetic tungsten(VI) dioxido complexes with the pyridine-2-thiolate ligand (PyS) and the pyrimidine-2-thiolate ligand (PymS) were synthesized and fully characterized. The OAT catalytic experiments revealed that [WO2(PyS)2] catalyzes the OAT from DMSO to PMe3 or PPh3 faster than the analogous molybdenum compound. In similar studies with [WO2(PymS)2], decomposition is observed upon dissolving in DMSO under the formation of the disulfide (PymS)2. Both the Mo and W complex reacted with PMe3, yielding a rare pentagonal bipyramidal MIVO species stabilized by two PMe3 molecules. Such a reduction requires expansion of the angle enclosed by the two least–square planes of the two aromatic ligands, which is easily occurring with the here used flexible ligands. These phosphine-stabilized species are models for the reduced form of the DMSO reductase active site and have as yet not been observed as intermediates in the oxygen transfer catalytic cycles for tungsten. When comparing the behavior of WIVO and MoIVO species in the presence of DMSO via UV–vis spectroscopy, we observed that the WIVO species is directly oxidized to the corresponding WVIO2 compound, while the MoIVO species first yields [Mo2O3(PyS)4], which further reacts to the related MoVIO2 complex. The higher tendency of Mo compounds to form μ-oxo dimers and their low solubility decelerate the OAT catalysis in this case. This is supported by DFT calculations, which confirmed that, unlike the tungsten variant, the oxygen transfer from [MoO2(PyS)2] to PMe3 is an exergonic process. In the case of OAT catalysis with PPh3, the molybdenum variants are reduced to the respective μ-oxo dimers, while no reduction was observed for any of the tungsten complexes. However, catalytic studies showed a higher performance of the tungsten compound, presumably due to the mechanism under the retention of the metal’s oxidation state +VI. This is biologically relevant as it delivers a possible explanation for the higher activity upon replacement of Mo by W in certain enzymes: Depending on both the substrate and the ligand set, the metal may participate in catalysis either through a net redox reaction (e.g., DMSO reductase) or by serving as an electrophile for the substrate (e.g., AH). In AH, retention of the oxidation state of tungsten is proposed, suggesting that the metal may act as an electrophile under certain circumstances rather than a redox center. Furthermore, this unexpected catalytic behavior and the fact that tungsten compounds are more temperature tolerant renders the far less explored metal in atom transfer catalysis a promising candidate for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, grant number P31583) and NAWI Graz is gratefully acknowledged. The authors especially thank Bernd Werner for measuring many NMR samples.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c01868.

Complete X-ray data, NMR spectra, UV data, and experimental procedures (PDF)

Author Contributions

M.Z.Ć. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. F.W. did DFT calculations. F.B. performed XRD measurements and analyzed the data. N.C.M. conceived the experiments and adjusted the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Open Access is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Majumdar A. Structural and functional models in molybdenum and tungsten bioinorganic chemistry: description of selected model complexes, present scenario and possible future scopes. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 8990–9003. 10.1039/c4dt00631c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelmann C. S.; Willistein M.; Heider J.; Boll M. Tungstoenzymes: Occurrence, Catalytic Diversity and Cofactor Synthesis. Inorganics 2020, 8, 44. 10.3390/inorganics8080044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hille R.; Schulzke C.; Kirk M. L.. Molybdenum and Tungsten Enzymes: Bioinorganic Chemistry:An Overview of the Synthetic Strategies. Reaction Mechanisms and Kinetics of Model Compounds; RSC Metallobiology Series No. 6; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holm R. H.; Solomon E. I.; Majumdar A.; Tenderholt A. Comparative molecular chemistry of molybdenum and tungsten and its relation to hydroxylase and oxotransferase enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 993–1015. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L.; Cohen H. J.; Rajagopalan K. V. Molecular Basis of the Biological Function of Molybdenum. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 5046–5055. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)42326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauret C.; Knowles R. Effect of tungsten on nitrate and nitrite reductases in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. Can. J. Microbiol. 1991, 37, 744–750. 10.1139/m91-128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M.; Moureaux T.; Caboche M. Tungstate, a molybdate analog inactivating nitrate reductase, deregulates the expression of the nitrate reductase structural gene. Plant Physiol. 1989, 91, 304–309. 10.1104/pp.91.1.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benemann J. R.; Smith G. M.; Kostel P. J.; McKenna C. E. Tungsten incorporation into Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. FEBS Lett. 1973, 29, 219–221. 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco J.; Niks D.; Hille R. Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of tungsten-substituted DMSO reductase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2018, 23, 295–301. 10.1007/s00775-017-1531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L. J.; Bailey S.; Bennett B.; Charnock J. M.; Garner C. D.; McAlpine A. S. Dimethylsulfoxide reductase: an enzyme capable of catalysis with either molybdenum or tungsten at the active site. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 299, 593–600. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buc J.; Santini C. L.; Giordani R.; Czjzek M.; Wu L. F.; Giordano G. Enzymatic and physiological properties of the tungsten-substituted molybdenum TMAO reductase from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 159–168. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm R. H. The biologically relevant oxygen atom transfer chemistry of molybdenum: from synthetic analogue systems to enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1990, 100, 183–221. 10.1016/0010-8545(90)85010-p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hille R. The reaction mechanism of oxomolybdenum enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1994, 1184, 143–169. 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark J. H.; Cooney J. J. A.; Wang J.-J.; Holm R. H. Synthetic analogues and reaction systems relevant to the molybdenum and tungsten oxotransferases. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1175–1200. 10.1021/cr020609d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pätsch S.; Correia J. V.; Elvers B. J.; Steuer M.; Schulzke C. Inspired by Nature—Functional Analogues of Molybdenum and Tungsten-Dependent Oxidoreductases. Molecules 2022, 27, 3695. 10.3390/molecules27123695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu P.; Nemykin V. N.; Sengar R. S. Substituent effect on oxygen atom transfer reactivity from oxomolybdenum centers: synthesis, structure, electrochemistry, and mechanism. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 6303–6313. 10.1021/ic900579s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyashenko G.; Saischek G.; Judmaier M. E.; Volpe M.; Baumgartner J.; Belaj F.; Jancik V.; Herbst-Irmer R.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Oxo-molybdenum and oxo-tungsten complexes of Schiff bases relevant to molybdoenzymes. Dalton Trans. 2009, 5655–5665. 10.1039/b820629e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caradonna J. P.; Reddy P. R.; Holm R. H. Kinetics, mechanisms, and catalysis of oxygen atom transfer reactions of S-oxide and pyridine N-oxide substrates with molybdenum(IV,VI) complexes: relevance to molybdoenzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 2139–2144. 10.1021/ja00215a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. C.; Samuel P. P.; Schulzke C. Synthesis, characterization and oxygen atom transfer reactivity of a pair of Mo(IV)O- and Mo(VI)O2-enedithiolate complexes - a look at both ends of the catalytic transformation. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 7523–7533. 10.1039/c7dt01470h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke C. Molybdenum and Tungsten Oxidoreductase Models. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 1189–1199. 10.1002/ejic.201001036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. R.; Gisewhite D.; Kalinsky A.; Esmail A.; Burgmayer S. J. N. Solvent-Dependent Pyranopterin Cyclization in Molybdenum Cofactor Model Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 8214–8222. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi M.; Fischer C.; Ghosh A. C.; Schulzke C. An Asymmetrically Substituted Aliphatic Bis-Dithiolene Mono-Oxido Molybdenum(IV) Complex With Ester and Alcohol Functions as Structural and Functional Active Site Model of Molybdoenzymes. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 486. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan C. J.; Slizys D. A.; Young C. G. New Insights into the Berg–Holm Oxomolybdoenzyme Model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6430–6436. 10.1021/ja9900959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M. S.; Berg J. M.; Holm R. H. Kinetics of oxygen atom transfer reactions involving oxomolybdenum complexes. General treatment for reactions with intermediate oxo-bridged molybdenum(V) dimer formation. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 3057–3062. 10.1021/ic00188a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oku H.; Ueyama N.; Kondo M.; Nakamura A. Oxygen atom transfer systems in which the μ-oxodimolybdenum(V) complex formation does not occur: syntheses, structures, and reactivities of monooxomolybdenum(IV) benzenedithiolato complexes as models of molybdenum oxidoreductases. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 209–216. 10.1021/ic00080a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schachner J. A.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C.; Peuronen A.; Lehtonen A. Dioxidomolybdenum(VI) and −tungsten(VI) complexes with tetradentate amino bisphenolates as catalysts for epoxidation. Polyhedron 2017, 134, 73–78. 10.1016/j.poly.2017.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupé A.; Hossain M. K.; Schachner J. A.; Belaj F.; Lehtonen A.; Nordlander E.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Dioxomolybdenum(VI) and -tungsten(VI) Complexes with Multidentate Aminobisphenol Ligands as Catalysts for Olefin Epoxidation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 3572–3579. 10.1002/ejic.201500055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.-L.; Tong L. H.; Dilworth J. R.; Ng D. K. P.; Lee H. K. New dioxo-molybdenum(VI) and -tungsten(VI) complexes with N-capped tripodal N2O2 tetradentate ligands: synthesis, structures and catalytic activities towards olefin epoxidation. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 4602–4611. 10.1039/b926864b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci G. C.; Donahue J. P.; Holm R. H. Comparative Kinetics of Oxo Transfer to Substrate Mediated by Bis(dithiolene)dioxomolybdenum and -tungsten Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 1602–1608. 10.1021/ic971426q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke C. Temperature dependent electrochemical investigations of molybdenum and tungsten oxobisdithiolene complexes. Dalton Trans. 2005, 713–720. 10.1039/b414853c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring A.; Schulzke C. Tungsten’s redox potential is more temperature sensitive than that of molybdenum. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 5623–5629. 10.1039/c000489h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmdach K.; Villinger A.; Seidel W. W. Spontaneous Formation of an η2 -C, S-Thioketene Complex in Pursuit of Tungsten(IV)-Sulfanylalkyne Complexes. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2015, 641, 2300–2305. 10.1002/zaac.201500576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.; Tiekink E. R. T.; Young C. G. pi-Acid/pi-Base Carbonyloxo, Carbonylsulfido, and Mixed-Valence Complexes of Tungsten. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 352–361. 10.1021/ic051456q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoura K.; Kondo M.; Nagasawa A.; Kanesato M.; Sakiyama H.; Oyama A.; Horiuchi H.; Nishida E.; Kondo T. Synthesis, molecular structure, and voltammetric behaviour of unusually stable cis-dioxobis(diisobutyldithiocarbamato)tungsten(VI). Inorg. Chim. Acta 2004, 357, 1265–1269. 10.1016/j.ica.2003.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Staley D. L.; Rheingold A. L.; Cooper N. J. Evidence for photodisproportionation of d1-d1 dimers [(Mo{S2CN(CH2Ph)2}2)2O] (M = molybdenum, tungsten) containing linear oxobridges and for oxygen atom transfer from [WO2{S2CN(CH2Ph)2}2] to triethylphosphine. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 4391–4396. 10.1021/ic00347a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jernakoff P.; Fox J. R.; Hayes J. C.; Lee S.; Foxman B. M.; Cooper N. J. Oxo Complexes of Tungstenocene via Oxidation of [W(η5-C5H5)2(OCH3)(CH3)] and Related Reactions. Organometallics 1995, 14, 4493–4504. 10.1021/om00010a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan T.; Mayilmurugan R.; Volpe M.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Faster oxygen atom transfer catalysis with a tungsten dioxo complex than with its molybdenum analog. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 7850–7857. 10.1039/c1dt10248f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehweiner M. A.; Wiedemaier F.; Belaj F.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Oxygen Atom Transfer Reactivity of Molybdenum(VI) Complexes Employing Pyrimidine- and Pyridine-2-thiolate Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 14577–14593. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham I. A.; Leigh G. J.; Pickett C. J.; Huttner G.; Jibrill I.; Zubieta J. The anion of pyrimidine-2-thiol as a ligand to molybdenum, tungsten, and iron. Preparation of complexes, their structure and reactivity. Dalton Trans. 1986, 1181. 10.1039/dt9860001181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa A. P.; Reis P. M.; Gamelas C.; Romão C. C.; Royo B. Dioxo-molybdenum(VI) and -tungsten(VI) BINOL and alkoxide complexes: Synthesis and catalysis in sulfoxidation, olefin epoxidation and hydrosilylation of carbonyl groups. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 1915–1921. 10.1016/j.ica.2007.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto H.; Hatakeda K.; Toyota K.; Tatemoto S.; Kubo M.; Ogura T.; Itoh S. A new series of bis(ene-1,2-dithiolato)tungsten(IV), -(V), -(VI) complexes as reaction centre models of tungsten enzymes: preparation, crystal structures and spectroscopic properties. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 3059–3070. 10.1039/c2dt32179c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyashenko G.; Jancik V.; Pal A.; Herbst-Irmer R.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Dioxomolybdenum(VI) and dioxotungsten(VI) complexes supported by an amido ligand. Dalton Trans. 2006, 1294–1301. 10.1039/b514873a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traill P. R.; Wedd A. G.; Tiekink E. R.T. Synthesis and Structure of cis-Dioxobis(pyrimidine-2-thiolato-N,S)molybdenum(VI). Aust. J. Chem. 1992, 45, 1933–1937. 10.1071/ch9921933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnáiz F. J.; Aguado R.; Pedrosa M. R.; Maestro M. A. Dioxomolybdenum(VI) thionates: molecular structure of dioxobis(pyridine-2-thiolate-N,S)molybdenum(VI). Polyhedron 2004, 23, 537–543. 10.1016/j.poly.2003.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Starke K.; Schulzke C.; Schmidt H.-G.; Noltemeyer M. Structural, Electrochemical, and Theoretical Investigations of New Thio- and Selenoether Complexes of Molybdenum and Tungsten. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 2006, 628–637. 10.1002/ejic.200500698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabi F.; Kakeshpour T.; Saidi M. R. Supported iron oxide nanoparticles: Recoverable and efficient catalyst for oxidative S-S coupling of thiols to disulfides. Catal. Commun. 2013, 40, 13–17. 10.1016/j.catcom.2013.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.-L.; Cowley A. R.; Dilworth J. R. Synthesis, structures, electrochemistry and properties of dioxo-molybdenum(VI) and -tungsten(VI) complexes with novel asymmetric N2OS, and partially symmetric N2S2, NOS2 N-capped tripodal ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2004, 357, 4358–4372. 10.1016/j.ica.2004.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-M.; Cheung K.-K.; Che C.-M. Preparation and crystal structure of a seven-co-ordinated oxotungsten(IV) complex of 2,2′:6′,2″:6″,2‴-quaterpyridine. Dalton Trans. 1993, 3515–3517. 10.1039/dt9930003515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan J. C.; Geib S. J.; Rheingold A. L.; Mayer J. M. Oxidative addition of carbon dioxide, epoxides, and related molecules to WCl2(PMePh2)4 yielding tungsten(IV) oxo, imido, and sulfido complexes. Crystal and molecular structure of W(O)Cl2(CO)(PMePh2)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 2826–2828. 10.1021/ja00243a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto H.; Sugimoto K. New bis(pyranodithiolene) tungsten(IV) and (VI) complexes as chemical analogues of the active sites of tungsten enzymes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008, 11, 77–80. 10.1016/j.inoche.2007.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi R.; Ćorović M. Z.; Buchsteiner M.; Vidovič C.; Belaj F.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. The Effect of Pyridine-2-thiolate Ligands on the Reactivity of Tungsten Complexes toward Oxidation and Acetylene Insertion. Organometallics 2021, 40, 3591–3598. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidovič C.; Peschel L. M.; Buchsteiner M.; Belaj F.; Mösch-Zanetti N. C. Structural Mimics of Acetylene Hydratase: Tungsten Complexes Capable of Intramolecular Nucleophilic Attack on Acetylene. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 14267–14272. 10.1002/chem.201903264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama H.; Yamamoto K.; Sauer A.; Ikeda H.; Spaniol T. P.; Tsurugi H.; Mashima K.; Okuda J. Reversible Transformation between Alkylidene, Alkylidyne, and Vinylidene Ligands in High-Valent Bis(phenolate) Tungsten Complexes. Organometallics 2016, 35, 932–935. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B. S.; Sung K.-M.; Holm R. H. Structural and Functional Bis(dithiolene)-Molybdenum/Tungsten Active Site Analogues of the Dimethylsulfoxide Reductase Enzyme Family. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7410–7411. 10.1021/ja001197y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra J.; Sarkar S. Oxo-Mo(IV)(dithiolene)thiolato complexes: analogue of reduced sulfite oxidase. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 3032–3042. 10.1021/ic302485c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cindrić M.; Matković-Čalogović D.; Vrdoljak V.; Kamenar B. Molybdenum(V) and molybdenum(IV) complexes with trifluorothioacetylacetone. X-ray structure of [Mo2O3{CF3C(O)CHC(S)CH3}4]. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 1998, 1, 237–238. 10.1016/S1387-7003(98)00060-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumisago M.; Matsubayashi G.-e.; Tanaka T.; Nishigaki S.; Nakatsu K. Synthesis, spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallographic analysis of (η3 -dithiobenzoato-SCS′)oxo(trithioperoxybenzoato-S,S′S″)molybdenum(IV) and μ-oxo-bis[bis(dithiobenzoato-SS′)oxomolybdenum(V)]. Dalton Trans. 1982, 121–127. 10.1039/dt9820000121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.-K.; Temple C.; Rajagopalan K. V.; Schindelin H. The 1.3 Å Crystal Structure of Rhodobacter sphaeroides Dimethyl Sulfoxide Reductase Reveals Two Distinct Molybdenum Coordination Environments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7673–7680. 10.1021/ja000643e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine A. S.; McEwan A. G.; Bailey S. The high resolution crystal structure of DMSO reductase in complex with DMSO. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 275, 613–623. 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin H.; Kisker C.; Hilton J.; Rajagopalan K. V.; Rees D. C. Crystal structure of DMSO reductase: redox-linked changes in molybdopterin coordination. Science 1996, 272, 1615–1621. 10.1126/science.272.5268.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F.; Löwe J.; Huber R.; Schindelin H.; Kisker C.; Knäblein J. Crystal structure of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus at 1.88 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 263, 53–69. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Starke K.; Schulzke C.; Hofmeister A.; Magull J. Different reaction behaviour of molybdenum and tungsten – Reactions of the dichloro dioxo dimethyl-bispyridine complexes with thiophenolate. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2007, 360, 3400–3407. 10.1016/j.ica.2007.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Schulzke C.; Yang Z.; Ringe A.; Magull J. Synthesis, structures and oxygen atom transfer catalysis of oxo-bridged molybdenum(V) complexes with heterocyclic bidentate ligands (N,X) X=S, Se. Polyhedron 2007, 26, 5497–5505. 10.1016/j.poly.2007.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.