Abstract

Transcriptional control of the low-temperature-inducible icdII gene, encoding the thermolabile isocitrate dehydrogenase of a psychrophilic bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1, was found to be mediated in part by a transcriptional silencer locating at nucleotide positions −560 to −526 upstream from the transcription start site of icdII. Deletion of the silencer resulted in a 20-fold-increased level of expression of the gene at low temperature (15°C) but not at high temperature (37°C). In addition, a CCAAT sequence located 2 bases upstream of the −35 region was found to be essential for the low-temperature-inducible expression of the gene. By deletion of this sequence, low-temperature-dependent expression of the gene was completely abolished. The ability of the icdII promoter to control the expression of other genes was confirmed by using a fusion gene containing the icdII promoter region and the promoterless icdI open reading frame, which encodes the non-cold-inducible isocitrate dehydrogenase isozyme of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. Escherichia coli transformants harboring icdII acquired an ability to grow rapidly at low temperature.

The bacterial isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), which catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate and CO2 coupled with the reduction of NADP+, plays an important role in the central metabolic pathway. Escherichia coli mutants defective in this enzyme have been shown to exhibit auxotrophy for glutamate (30). There have been many reports on the purification and biochemical characterization of the enzyme from a wide range of bacterial sources (6, 7, 10, 20–22). Most bacteria contain only one type of IDH, either a dimer composed of ca. 45-kDa subunits or a monomer of ca. 80 kDa (28). Previously, we reported the coexistence of two types of IDH in Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1, a psychrophilic bacterium (15, 24): a dimeric enzyme (IDH-I) with thermostability comparable to that of mesophiles and a monomeric enzyme (IDH-II) with extreme thermolability at above 25°C. Kinetic studies on the purified IDH isozymes suggested that the catalytic ability of IDH-II at low temperature is much higher than that of IDH-I (24). In addition, the amino acid sequences of the isozymes differed substantially (16), and the transcriptions of the cloned genes encoding the two IDH isozymes were confirmed to be differently regulated in E. coli (28). The transcription of the gene icdI, encoding IDH-I, was induced by acetate, while that of the gene icdII, coding for IDH-II, was induced by low temperature. These results imply that acquisition of a low-temperature-inducible promoter and a cold-adapted enzyme such as IDH-II might be crucial to facilitate the adaptation of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 to low temperature. In ectothermic multicellular organisms, such as the sea anemone, the activities of some enzymes in the intermediary metabolism have been reported to increase during the acclimation to cold temperature (14, 28), although the mechanism of the increase remains unknown.

Regarding bacterial adaptation to low temperature, recent findings of low-temperature-dependent expression of cold shock genes in mesophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria are of great interest (2, 18, 19). A shift down of the cultural temperature to near the minimum limit for growth induces the transient synthesis of cold shock proteins (Csps). This response to cold has been extensively studied in a mesophilic bacterium, E. coli. CspA, the major cold shock protein of E. coli, has been demonstrated to act as a transcriptional activator for other cold shock genes, i.e., gyrA and hns (17, 19). It has been also demonstrated that CspA can bind to a DNA probe containing the sequence CCAAT, which is located in the promoter regions of the cold shock genes (19). However, little is known about the effects of temperature on gene expression of psychrophilic bacteria, which are permanently exposed to low temperature. In this paper, we describe the nucleotide sequences of cis-acting elements for the low-temperature-inducible promoter of icdII, encoding a thermolabile, monomeric type of IDH isozyme (IDH-II) of a psychrophilic bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. We show also that growth of E. coli cells at low temperature is improved by transformation with a plasmid carrying icdII.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All restriction endonucleases were obtained from Nippon Gene (Toyama, Japan), Toyobo (Osaka, Japan), or New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.). AmpliTaq DNA polymerase was from Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, Conn.). A Kilo-Sequence deletion kit, exonuclease III, and mung bean nuclease were purchased from Takara Shuzo (Kyoto, Japan). Poly(dI-dC) was obtained from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany). [γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]dCTP were purchased from ICN Biomedical Inc. (Irvine, Calif.). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The psychrophilic bacterium Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 was grown at 15°C as previously described (15). The strains of E. coli and the plasmids used are shown in Table 1. E. coli DEK2004, a mutant defective in icd (a gift from Peter Thorsness), or E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) was used as a host for transformation by icd genes. The medium for the growth of this strain was Luria broth (LB) (27) or morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-based medium (23), supplemented with 2% sodium succinate. For plate culture, the liquid medium was solidified with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. E. coli XL1-Blue was used for propagation of plasmids. Media for this strain were supplemented with a trace amount of thiamine (about 10 to 100 nM). When necessary, media were supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin and/or 15 μg of tetracycline per ml. Plasmids pIS102 and pIS202, which are pBluescript KS(+) with insertions of icdI and icdII, respectively, were constructed as described previously (16). Plasmid pSS512 was constructed by insertion of the 1.9-kbp EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pTK512 (a gift from Peter Thorsness) containing the E. coli icd gene into EcoRI-HindIII-digested pBluescript SK(+). Plasmid pIS001, which is pBluescript KS(+) carrying both the icdI and icdII genes, was constructed by inserting an XbaI-digested DNA fragment (6.3 kbp) of the λ genomic library of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. To investigate the ability of the low-temperature-inducible icdII promoter to control the expression of other genes, an icdII-icdI fusion plasmid, pTS601, in which expression of icdI could be regulated under the control of icdII promoter, was generated by PCR with standard techniques and the forward primer 5′-ATGACCAATAAAATCATCATTCCAACGAC-3′ (nucleotides +40 to +68 from the icdI transcriptional initiation site) and reverse primer 5′-TGAAATTCCTATTTTAATTAGCTAAAAGC-3′ (complement to nucleotides +96 to +68 from the icdII transcriptional initiation site). DNA of pIS001 was used as the template for the reaction. To create pMS42C and pMSF8C, which lack the sequence CCAAT located 2 bases upstream from the −35 region of the icdII promoter, PCR was applied with the forward primer 5′-AATTTATAGGGTTTGGTAAGTTTTCTAACT-3′ (nucleotides −37 to −8 from the icdII transcriptional start site), the reverse primer 5′-CCTACACAATATTTCTAAAAAACACTTAGA-3′ (complement to nucleotides −43 to −72 from the icdII transcriptional start site), and pMS42 and pMSF8, respectively, as the templates. Similarly, PCR techniques were applied to create pMS42S and pMSF8S, which lack a stem-loop-like structure located at nucleotides +44 to +87 from the transcriptional start site of icdII, by using the forward primer 5′-GGAATTTCAATGAGCACTGATAACTCAAAA-3′ (nucleotide positions +88 to +117 from the icdII transcriptional start site) and reverse primer 5′-CGACCCTCATGTTCGGTAATTGAACAAATC-3′ (complement to the nucleotide sequence +43 to +14 from the icdII transcriptional start site). Overlapping deletions of the upstream noncoding region of the icdII promoter were produced by the method of Henikoff (13) with a Kilo Sequence Deletion Kit (Takara Shuzo) and pIS202. DNA was extracted from the bacterial cells and purified as described previously (16). All DNA nucleotide sequences were determined by the cycle sequencing method by using -21M13 and M13 reverse dye-primer with an ABI 373 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). The sequences were analyzed and compared by using the Genetyx computer program (Software Development Co., Tokyo, Japan).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 | Psychrophilic bacterium | 29 |

| E. coli | ||

| K-12 | Wild type | |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 lac endA1 gryA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 (F′ proAB lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10) | Stratagene |

| DEK2004 | icd trp recA; tetracycline resistant | 30 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS(+) or SK(+) | ori ColE1; ampicillin resistant | Stratagene |

| pIS001 | Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 icdI and icdII genes cloned into the XbaI site of pBluescript KS(+) | This study |

| pIS102 | Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 icdI gene cloned into the EcoRV-XbaI sites of pBluescript KS(+) | 16 |

| pIS202 | Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 icdII gene cloned into the XbaI-SacI sites of pBluescript KS(+) | 16 |

| pMS and pMSF series | icdII upstream deletion plasmids derived from pIS202 | This study |

| pTS601 | pBluescript KS(+) with an insertion of a fused gene of the Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 icdII upstream region and icdI ORF | This study |

| pTS602 | 5.5-kbp SpeI fragment derived from pTS601 was ligated | This study |

| pSS512 | E. coli icd gene derived from pTK512 (30) was cloned into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of pBluescript SK(+) | 28 |

RNA isolation and Northern (RNA) blot analysis.

Total RNAs from the bacterial cells were extracted and purified by a single-step RNA isolation method as described previously (5). The extracted RNAs were separated on agarose gels (1.2%) containing 0.66 M formaldehyde, transferred onto nylon membranes, and then hybridized with appropriate radiolabeled DNA fragments as described previously (28). After hybridization, the membranes were washed successively in SSC (1× SSC is 150 mM NaCl plus 15 mM sodium citrate) containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate as follows: 2× SSC at room temperature for 20 min, 1× SSC at 65°C for 15 min, and 0.1× SSC at 65°C for 20 min. Autoradiography was performed by exposing the membranes to X-ray film (Fuji RX medical X-ray film) for over 24 h at −80°C. The amount of mRNA that hybridized with each specific probe was quantified from the autoradiographs by densitometry.

Western blot analysis.

The procedures for preparation of antibodies raised against the IDH isozymes were described previously (15). The purified isozymes (0.2 μg) and proteins (10 μg) in cell extracts from E. coli mutants harboring each plasmid carrying an insertion of icdI or icdII were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (7.5%) gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and subjected to Western blot analysis with the ECL Western blotting detection system (Amersham) and rabbit anti-IDH-I or -II antibody.

Primer extension analysis.

We chemically synthesized the following 32-mer oligonucleotide as the primer for icdII: 5′-GCTTGAATAATGGGTAATAAAGAATACGTCGC-3′, complementary to the internal region from base +185 to +154 of icdII. The primer was 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. Total RNA isolated from Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 or E. coli transformants was hybridized with the labeled primer. The primer extension reaction (27) was done by using Rous-associated virus 2 reverse transcriptase (Takara Shuzo Co.), and products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel with a sequencing ladder generated as described previously (16).

Enzyme assay.

Sonic cell extract of the bacterial cells was obtained as described previously (15). IDH activities were assayed spectrophotometrically at 40°C for IDH-I at or 20°C for IDH-II as described previously (21). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount capable of catalyzing the reduction of 1 μmol of NADP+ per min. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (3).

Figures.

All figures were produced by using Adobe Photoshop 4.0/IBMPC.

RESULTS

Effects of deletions of the upstream noncoding region on the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII.

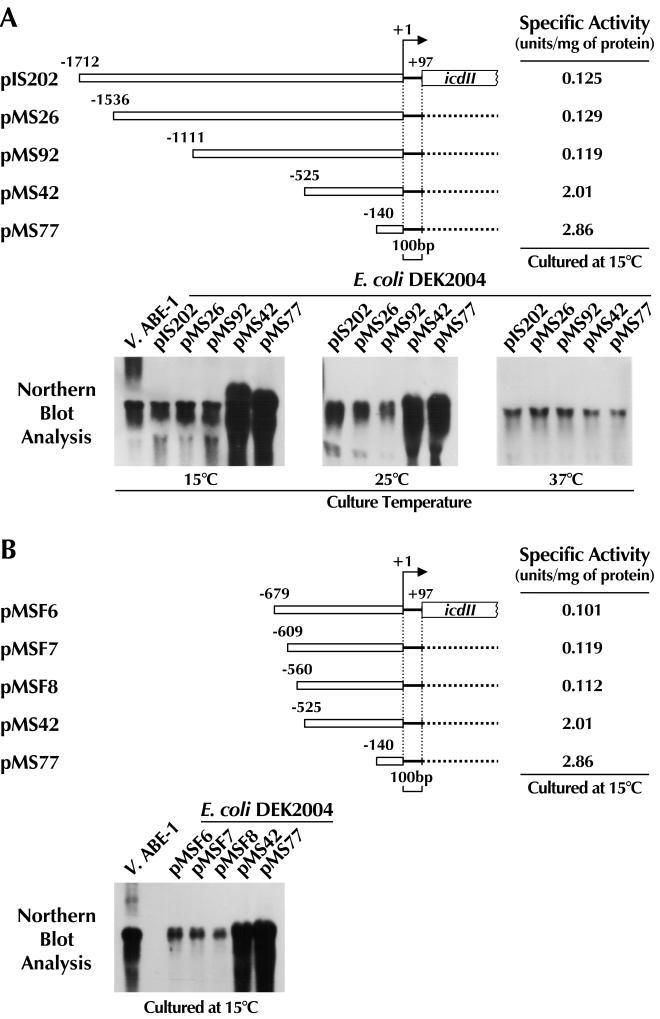

Plasmid pIS202, which contains 4.2-kbp XbaI-SacI fragment of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 genomic DNA, is an icdII expression plasmid (16). The upstream noncoding region of the icdII open reading frame (ORF) is 1,808 bp long. Sequencing revealed no ORF or unique sequence, such as that forming a stem-loop structure, absolute tandem repeat, or reverse repeat, in this upstream region. To examine whether a cis-acting element(s) for the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII is present in this upstream noncoding region, we made a series of deletion mutations from the 5′ end of the upstream noncoding region of the XbaI-SacI insert in pIS202 (Fig. 1). Effects of the deletions on the low-temperature-inducible expression of icdII were examined by measuring the levels of the icdII mRNA and enzymatic activity in E. coli transformants harboring each construct grown at different temperatures (15, 25, and 37°C). As shown in Fig. 1A, the transformants harboring either pMS26 (177-base deletion) or pMS92 (602-base deletion) expressed almost the same level of icdII mRNA as those harboring the control plasmid (pIS202). However, the level of icdII mRNA was greatly increased when the transformants harboring pMS42 (1,188-base deletion) or pMS77 (1,573-base deletion) were cultured at temperatures of below 25°C but not when they were cultured at 37°C. The changes in the level of enzymatic activity of the icdII product (IDH-II) were found to coincide with those of the icdII mRNA (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that a cis-acting element(s) which can repress the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII is present in a region between nucleotide positions −1,111 and −525. In order to determine the sequence required for the repression of icdII expression at low temperature, more deletion mutants of this region were constructed. The expression level of the icdII mRNA was examined by using transformants harboring pMSF6 (1,034-base deletion), pMSF7 (1,104-base deletion), or pMSF8 (1,153-base deletion) and cultured at 15°C. As shown in Fig. 1B, none of these plasmids conferred derepression of the low-temperature-dependent gene expression on the transformants. These results indicate that the sequence of 35 bp located at nucleotide positions −560 to −526 (Fig. 2) has the function of repressing the low-temperature-dependent icdII expression.

FIG. 1.

Deletion analysis of the upstream noncoding region of icdII of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. Each plasmid was constructed by successive deletion from the 5′ end of pIS202 as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers indicate nucleotide positions from the transcriptional start site (+1). E. coli DEK2002 was used as the host. Each transformant was cultured at the temperatures indicated and harvested for analyses of mRNA and enzymatic activity. The procedures for the analyses are described in Materials and Methods. Two and 10 μg of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 (V. ABE-1) and the transformant RNAs, respectively, were used for detection of the icdII mRNA. A radiolabeled 828-bp PstI fragment (+640 to +1267) of icdII was used as a probe.

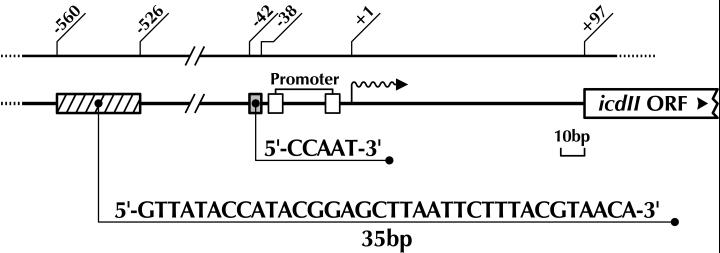

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the two cis-acting elements responsible for icdII expression. The numbers indicate nucleotide positions as described for Fig. 1. The hatched box indicates the position of the 35-bp sequence (−560 to −526) acting as a silencer. The gray box shows the position of the CCAAT sequence (−42 to −38) which is a putative common motif for E. coli cold-inducible genes. Positions −35 and −10 are indicated by open boxes.

The sequence CCAAT, located in the vicinity of the promoter region, is required for the low-temperature-dependent expression of the icdII gene.

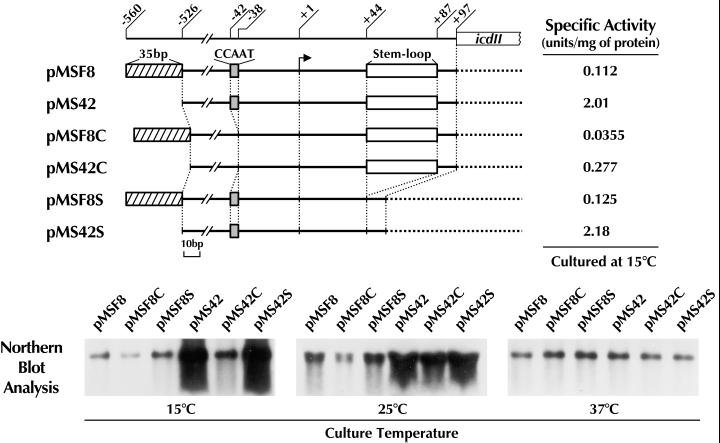

Although the deletion of the 35-bp sequence, which acts as a transcriptional silencer, resulted in a 20-fold increase in the expression of the icdII gene at 15°C, low-temperature-dependent expression of the gene still occurred (Fig. 1A; compare the expression levels at 15 and 37°C). This result suggests that some element(s) other than the silencer is responsible for the low-temperature-dependent gene expression. Computer analysis of the noncoding region of nucleotide positions −525 to +97 revealed that there are two unique sequences in the vicinity of the promoter region of icdII. One is CCAAT, located 2 bases upstream of the −35 region of icdII. This sequence has been suggested to be a common motif of low-temperature-inducible genes of E. coli (19, 25). The other is a sequence of 44 bp which is located downstream of the promoter (positions +44 to +87). Judging from sequence analysis, the latter sequence seems to form a stem-loop structure. To investigate the possibility that these two sequences are responsible for regulating the expression of icdII at low temperature, we attempted to construct expression plasmids carrying icdII without either of the two sequences. For this purpose, PCR techniques were applied as described in Materials and Methods. The constructs pMSF8C and pMS42C are derivatives with CCAAT deleted from pMSF8 and pMS42, respectively. The difference between pMSF8C and pMS42C is that the former contains the 35-bp silencer sequence at the 5′ end of the noncoding region of icdII but the latter does not (Fig. 3). Similarly, pMSF8S and pMS42S are derivatives with the 44-bp sequence deleted from pMSF8 and pMS42, respectively. The regulatory role of the CCAAT or 44-bp sequence in the low-temperature dependent expression of icdII was investigated by measuring the levels of icdII mRNA in E. coli transformants harboring each plasmid cultured at different temperatures. The results are shown in Fig. 3. The expression levels at 37°C were similar in all cells with a plasmid, and longer exposure to the film was required to detect the signals. This result indicates that the expression level of icdII mRNA at 37°C is low and that no upstream region of the gene specifically responds to this temperature. At culture temperatures of below 25°C, the transformants harboring pMSF8C expressed less icdII mRNA than those harboring the control plasmid (pMSF8). The effect of the deletion of the CCAAT sequence on the icdII expression at low temperature was much more obvious when plasmid pMS42C was used as the icdII expression vector (compare with the control, pMS42). In contrast, deletion of the 44-bp sequence had no effect on the expression of icdII at any temperature. The changes in the levels of mRNA were coincident with those in the levels of IDH-II specific activity in the cell extract prepared from the cells grown at 15°C. These results indicate clearly that the sequence CCAAT located 2 bases upstream of the promoter region plays an essential role in the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII.

FIG. 3.

Effects of deletion of the CCAAT sequence on the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII. (Upper panel) Schematic representation of the upstream noncoding region of the icdII gene. Plasmids used in this experiment are indicated on the left. The numbers are nucleotide positions as described for Fig. 1. Hatched, gray, and open boxes indicate the positions of the 35-bp (−560 to −526), CCAAT (−42 to −38), and 44-bp (+44 to +87) sequences, respectively. E. coli DEK2004 harboring each plasmid was cultured in LB medium at the temperatures indicated and harvested for mRNA and enzymatic analyses. The procedures for the analyses were the same as those described for Fig. 1. The specific activities of IDH-II in a cell extract from the cells grown at 15°C are indicated on the right. (Lower panel) Northern blot analysis of icdII mRNA. Total RNA (10 μg) extracted from each E. coli transformant cultured at the temperatures indicated was used for each lane. The radiolabeled probe used for detection of the icdII mRNA was the same as that described for Fig. 1.

Effects of temperature on icdI expression under the control of the icdII promoter.

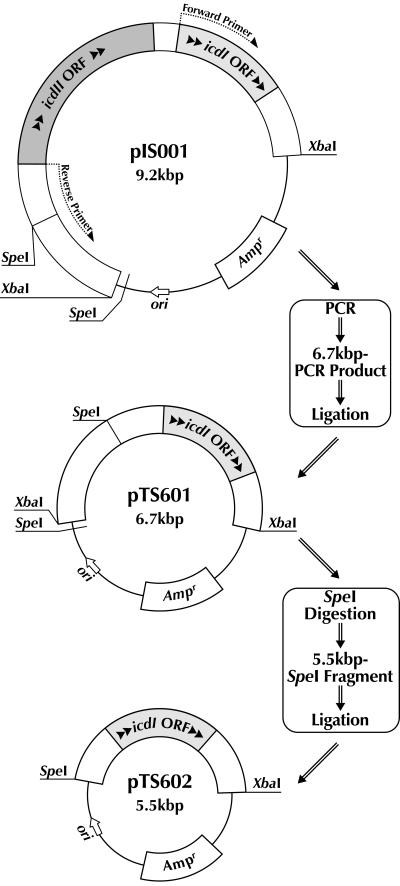

We previously demonstrated that icdI and icdII are located adjacent to each other on the chromosome of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1; however, the expression of icdI is induced by acetate but not by low temperature (16, 28). To elucidate whether the icdII promoter can control the expression of other genes, we constructed plasmids carrying the icdII promoter-icdI ORF fusion as described in Materials and Methods. These constructs are schematically shown in Fig. 4. pTS601 contains the whole length of the upstream noncoding region of icdII. The 3′ end of this region was connected with the icdI ORF in frame. In the plasmid pTS602, the icdI ORF was similarly connected with the upstream noncoding region with 1,190 bases deleted from the 5′ end. As described above, this deletion resulted in an increase of the icdII expression level at low temperature. The expression of the fused genes was determined at the levels of mRNA, protein, and enzymatic activity in the transformants harboring pTS601 or pTS602 grown at different temperatures. As seen in Fig. 5, the obtained data, including Western blot analysis (data not shown), indicate that the expression level of icdI was increased by decreasing the growth temperature. These results clearly indicate that the promoter of icdII is able to control the expression of other genes and that no region of the icdII ORF is responsible for low-temperature-inducible expression of icdII.

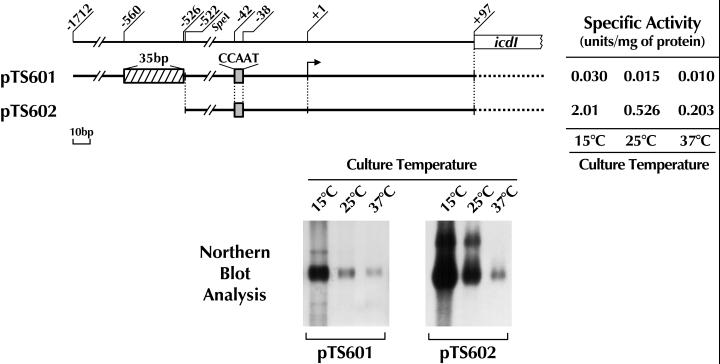

FIG. 4.

Construction of plasmids pTS601 and pTS602, carrying an icdII-icdI fusion gene. Plasmid pTS601 was constructed by the PCR method with pIS001 as a template such that it contained the whole length of the upstream noncoding region of icdII fused with the icdI ORF. Nucleotide sequences of the primers used for PCR and the procedures used are described in Materials and Methods. Plasmid pTS602 was made by self-ligation of a 5.5-kbp SpeI fragment from pTS601.

FIG. 5.

Low-temperature-dependent expression of icdI under the control of the icdII promoter. (Upper panel) Schematic representation of the icdII-icdI fusion gene. Numbers indicate the nucleotide positions from the transcriptional start site of icdII. Plasmids used in this experiment are indicated on the left. The hatched and gray boxes show the positions of the 35-bp silencer and CCAAT sequence, respectively. E. coli DEK2004 was used as the host. E. coli transformants harboring each plasmid were cultured in LB medium at the temperatures indicated and harvested for analyses of mRNA and enzymatic activity. The specific activity of IDH-I in the cell extracts prepared from each transformant is indicated on the right. (Lower panel) Northern blot analysis of icdI mRNA. Total RNA (20 μg) extracted from each transformant cultured at the temperatures indicated was used for each lane. A radiolabeled 343-bp SacI fragment (+34 to +376) of icdI was used for detection of the icdI mRNA.

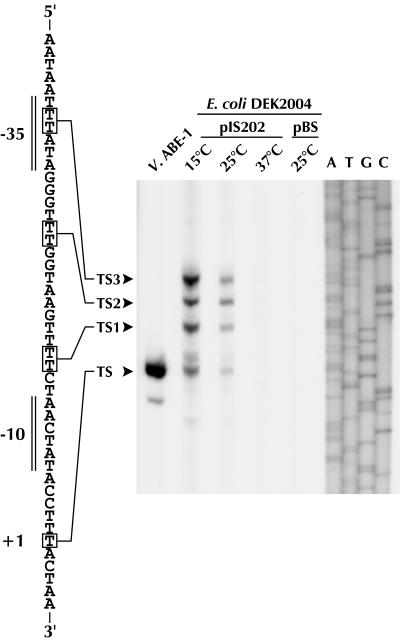

We next examined the effect of the sequence CCAAT, located at position −38 in the icdII promoter region, on the low-temperature-inducible expression of the fused gene, and we found that it too was required for the expression (data not shown). In addition, we examined whether the transcription initiation site of icdII in E. coli is the same as that in Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 (16). Total RNA isolated from E. coli DEK2004 cells harboring pIS202 was used for a primer extension reaction. A 5′ transcript end generated from a site designated TS, which was the same transcription initiation site determined with RNA from Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1, was observed (Fig. 6). As expected, the amount of this transcript was decreased with increasing culture temperature for the transformants. In addition to this transcript, we saw three or six starts upstream of TS at base −14 or −15 (TS1), −24 or −25 (TS2), and −33 or −34 (TS3). The bands of these transcripts often gave doublets. These results suggest that icdII can be transcribed from multiple sites in E. coli and that one of the sites is the same as in Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1.

FIG. 6.

Primer extension analysis. Products of primer extension with a primer complementary to icdII are shown. V. ABE-1, total RNA (40 μg) isolated from Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 cells grown at 15°C was used as the template. E. coli DEK2004 transformants harboring pIS202 were grown at the indicated temperatures, and total RNA (40 μg) obtained from the transformants was used as the template for each analysis. pBluescript (pBS) was used as a vector control. A, T, G, and C, sequencing ladders of pIS202, using the same primer. Positions of the primer extension products are indicated with arrowheads, and +1 on the sequence shown on the left is the transcription initiation site determined previously (16).

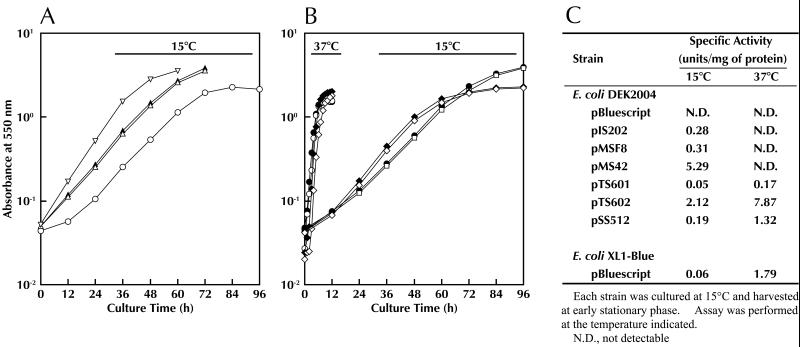

Effects of icdII on the growth of E. coli at low temperature.

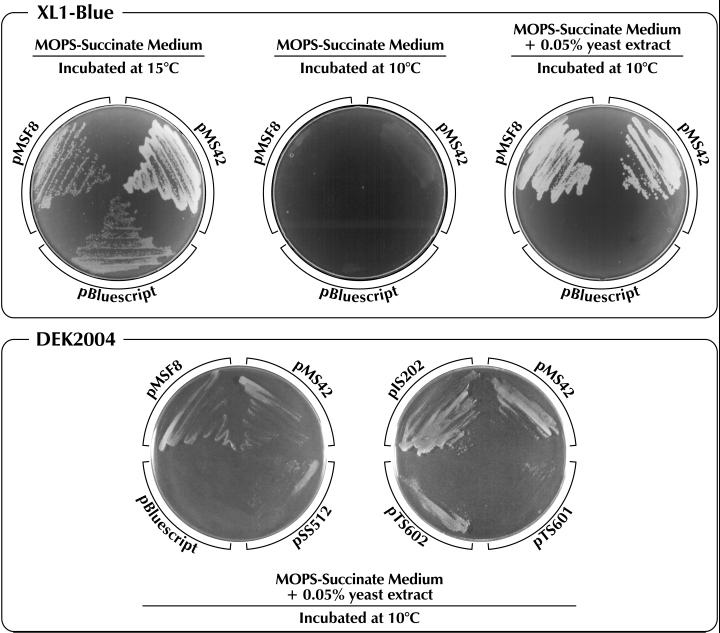

The icdII gene product, IDH-II, is a thermolabile enzyme and shows higher catalytic efficiency at low temperature than the other isozyme, IDH-I (16, 24). The presence of such an enzyme may be important for the growth of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 at low temperature. To evaluate the physiological role of IDH-II, we examined the growth of E. coli DEK2004 transformants harboring plasmid pIS202, pMSF8, or pMS42, which contain an icdII insert. Effects of the icdI gene on low-temperature growth of E. coli were also examined by using plasmids pTS601 and pTS602, which contain icdII-icdI fusion genes. Plasmid pSS512, which contains the E. coli icd gene, was used as a control. In addition, E. coli XL1-Blue, which contains its own icd gene, was used to compare the effects of transformation with various plasmids. The results are shown in Fig. 7. At the optimum temperature (37°C) for the growth of E. coli, no difference in the growth rate of any transformant in LB medium was observed (Fig. 7B). This result supports the observation that IDH-II is completely inactivated at this temperature (16, 24). However, the transformants harboring different plasmids showed different growth rates at low temperature (15°C) in the same medium. The growth rate of the transformants harboring pSS512 was essentially the same as that obtained with the transformants harboring the vector control (Fig. 7B). However, the rate was increased (in order) for the transformants harboring pSS512, pMSF8 or pIS202, and pMS42; the doubling times of the transformants harboring pSS512, pMSF8 or pIS202, and pMS42 were 11.3, 9.0, and 6.8 h, respectively (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, transformation with pTS601 or pTS602 had little effect (Fig. 7B), although the levels of IDH-I activity at 15 and at 37°C differed greatly (Fig. 7C). To confirm that the observed differences in the growth rates were caused by different levels of IDH-II activity, we assayed the enzymatic activity in the cell extract prepared from each transformant grown at 15°C. The specific activity of the enzyme in the transformants harboring pMS42 was about 20-fold higher than that in the transformants harboring pMSF8 or pIS202 (Fig. 7C). Since IDH is a key enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and E. coli mutants defective in this enzyme exhibit auxotrophy for glutamate, we examined whether IDH-II influences the growth rate of E. coli at low temperature on an agar plate of minimal medium containing succinate as the sole source of carbon and energy. In comparison with E. coli IDH, E. coli XL1-Blue containing the icd gene was transformed with pMSF8 or pMS42. Each transformant was streaked on the agar plate and incubated at 15 or 10°C. The results are shown in Fig. 8. At 15°C, all transformants, including the cells harboring the vector control, formed visible colonies within 9 days. However, at 10°C, no transformants formed visible colonies even after 2 weeks. When the minimal medium was supplemented with 0.05% yeast extract, the transformants harboring the plasmid containing icdII formed visible colonies at 10°C. Furthermore, we examined the difference between the IDH-I and -II isozymes of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 by using E. coli DEK2004 as a host for transformation. At 10°C, the transformants harboring either of the plasmids containing icdII were able to grow well, while those harboring a plasmid containing icdI or E. coli icd grew only slightly (Fig. 8). These results clearly confirm the previous observation that IDH-I is unable to enhance the growth rate of E. coli at low temperature, even though it is overproduced under the control of the icdII upstream region (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Growth of E. coli transformants harboring 5′-deleted icdII or an icdII-icdI fusion gene. (A) E. coli DEK2004 was transformed with vector [pBluescript KS(+)] (○), pMS42 (▿), pIS202 (▴), or pMSF8 (▵). (B) E. coli DEK2004 was transformed with pTS601 (⧫), pTS602 (◊), or pSS512 (□). As a control, E. coli XL1-Blue, which has its own icd gene, was also transformed with the vector (●). Other symbols are the same as in panel A. Each transformant, precultured in LB medium at 37°C for 16 h, was inoculated in fresh LB medium and cultured at 15 or 37°C. (C) Specific activity of IDH determined with crude extract prepared from each transformant. Details of assay conditions are described in Materials and Methods. Note the thermolability of IDH-II at 37°C.

FIG. 8.

Low-temperature growth of E. coli transformants harboring the icdII gene. (Upper panel) E. coli XL1-Blue was transformed with pMSF8 or pMS42. (Lower panel) E. coli DEK2004 was used as the host and transformed with the indicated plasmid. pBluescript was used as a vector. E. coli transformants harboring each plasmid were streaked on MOPS-succinate or MOPS-succinate-yeast extract agar plates and incubated at 10 or 15°C. Photographs were taken 2 weeks after the inoculation.

DISCUSSION

The present results indicate that the expression of low-temperature-inducible icdII, which codes for a thermolabile monomeric IDH isozyme of a psychrophilic bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 (16, 28), is controlled by two different cis-acting elements in the upstream noncoding region. The cloned icdII has a stretch of upstream noncoding sequence of about 1,800 bp (Fig. 1A). Serial deletions from the 5′ end of the upstream noncoding region of the icdII gene revealed that one of the cis elements is located at positions −560 to −526 from the transcription initiation site. The deletion of this element (a 35-bp sequence) resulted in up to a 20-fold increase in the icdII mRNA level at low temperature (15 or 25°C) but not at high temperature (37°C) (Fig. 1). These results indicate that this sequence acts as a negative element or transcriptional silencer at low temperature and that some other element(s) located downstream, at position −526, still functions to regulate the low-temperature-dependent expression of the gene. Interestingly, thermoregulation of transcription of the E. coli papI gene, which is expressed at high temperature (37°C, but not below 25°C), has been reported to be controlled through transcriptional silencing by the drdX product, a histone-like DNA binding protein (12). The mutation in drdX resulted in derepressed expression of the papI gene. In our case, however, the deletion of the 35-bp cis-acting element resulted in incomplete derepression, because the expression level at 37°C was not altered. Although the effects of temperature on the expression of the papI and icdII genes are completely different, the mechanisms of the thermoregulation of expression of these bacterial genes may be similar. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of this 35-bp cis-acting element did not reveal any homologous sequences in the databases. Nevertheless crude extracts prepared from E. coli or Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 were found to contain a protein factor which can bind specifically to DNA fragments containing this element (data not shown).

A candidate for the second cis-acting element located downstream at position −526 is the CCAAT sequence 2 bases upstream of the −35 region. This sequence, in the proximal region of promoter, has been proposed as a common motif of E. coli cold shock genes (19, 25). However, no direct evidence is available to show that this sequence is responsible for the low-temperature-dependent expression of the bacterial genes. Our plasmid constructs, which lack the CCAAT sequence at nucleotide position −38 of the icdII gene, lost completely the ability to respond to low temperature when the expression of icdII in E. coli transformants harboring each of the plasmids was examined (Fig. 3). When the icdI gene, which is nonresponsive to low temperature, was expressed under the control of the upstream noncoding region of icdII, the effects of the deletions of the 35-bp or CCAAT sequence on the expression were essentially the same as those observed with the icdII gene. Thus, it is evident that these two sequences act as cis elements for the regulation of icdII gene expression. In addition, the results for the icdII-icdI fusion gene clearly indicate that the low-temperature-inducible promoter of icdII is strong enough to control the expression of other genes and that no region of the icdII ORF is responsible for the low-temperature-dependent expression. We propose that the 35-bp sequence located at nucleotide positions −560 to −526 controls the response to low temperature by silencing the gene expression, whereas the CCAAT sequence located at nucleotide positions −42 to −38 is essentially required for the low-temperature response. In E. coli, it was found that icdII was transcribed from multiple sites, including T+1(TS) determined previously with RNA isolated from Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 (16). The reason for this is not known at present. The putative promoter motifs at positions −10 and −35 for icdII are TTTATA and AACTAT (16) and exhibit relatively low homology (37.3%) to the consensus sequence of the E. coli ς60 recognition site (26). Within the limits of −20 to −78 bases upstream of T+1(TS), there are three promoter motifs with low homology (37.3 to 43.2%), which correspond to TS1, TS2, and TS3 (Fig. 6). ς60 of E. coli RNA polymerase might recognize these sequences. The detailed mechanism of the low-temperature-dependent expression of icdII gene still remains unclear; however, a similar mechanism may operate to control the gene expression in E. coli and Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1, because low-temperature-inducible expression of the icdII gene was observed in both bacteria (28).

Recently, low-temperature induction of cspA, encoding the major cold shock protein of E. coli, has been reported to be the result of increased stabilization of cspA mRNA at low temperature, but not at the level of transcription (9). Indeed, the promoter of cspA is not cold inducible (8), and the 5′ untranslated region of cspA mRNA is involved in the regulation of the transient synthesis of CspA during the bacterial acclimation to low temperature (8, 9, 11). Generally, cold shock proteins are characterized as a group of proteins that are synthesized upon cold shock and disappear after adaptation to low temperature. However, icdII of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 is not categorized as a cold shock gene, because it is expressed constitutively at low temperature. This difference may be reflected in the nature of the promoters.

One of the aims of our study is to clarify the mechanisms underlying the bacterial adaptation to low temperature. Despite many biochemical reports on psychrophilic bacteria, the importance of a cold-adapted enzyme for growth at low temperature has yet to be demonstrated directly. IDH-II of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 is thermolabile and exhibits high catalytic efficiency at low temperature (24, 28). It is interesting that E. coli, a mesophilic bacterium, acquired the ability to shorten its doubling time at low temperature on insertion of a plasmid carrying icdII, encoding IDH-II, whereas transformation with a plasmid carrying the homologous E. coli icd gene conferred no such ability to the bacteria (Fig. 7 and 8). In addition, an E. coli icd mutant carrying a plasmid with another mesophilic bacterial icd gene, cloned from Azotobacter vinelandii, the product of which is a monomeric IDH and exhibits a high specific activity at 37°C (1, 7), failed to form a visible colony on a minimal medium agar plate at 10°C (our unpublished observation). The importance of IDH-II was further demonstrated by the observation that plasmid pTS602, which can overexpress IDH-I, has little effect on bacterial growth at low temperature (Fig. 7 and 8). Over the course of evolution, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 acquired a set of cold-adapted enzymes and a low-temperature-inducible promoter. This acquisition might have facilitated bacterial adaptation to low temperature.

ADDENDUM

During the review of this article, a paper describing reassignment of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 was published (32). From a phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequencing, this bacterium was found to be more closely related to Colwellia species than to Vibrio species. The new name Colwellia maris sp. nov. has been proposed for Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Thorsness for donating the E. coli icd mutant DEK2004 and plasmid pTK512. We are grateful to the members of the Research Center for Molecular Genetics, Hokkaido University, for allowing us to use their facilities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrera C R, Jurtshuk P. Isolation and purification of the isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP+) of Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;191:193–195. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger F, Morellet N, Menu F, Potier P. Cold shock and cold acclimation proteins in the psychrophilic bacterium Arthrobacter globiformis S155. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2999–3007. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.2999-3007.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapt-Charbier M-P, Schouler C, Lepeuple A S, Gripon J C, Chopin M C. Characterization of cspB, a cold-shock-inducible gene from Lactococcus lactis, and evidence for a family of genes homologous to the Escherichia coli cspA major cold shock gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5589–5593. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5589-5593.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung A E, Franzen J S. Oxidized triphosphopyridine nucleotide specific isocitrate dehydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii: purification and characterization. Biochemistry. 1969;8:3175–3184. doi: 10.1021/bi00836a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colman R F. Aspects of the structure and function of the isocitrate dehydrogenases. Pept Protein Rev. 1983;1:41–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang L, Jiang W, Bae W, Inouye M. Promoter-independent cold-shock induction of cspA and its derepression at 37°C by mRNA stabilization. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:355–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2351592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang L, Hou Y, Inouye M. Role of the cold-box region in the 5′ untranslated region of the cspA mRNA in its transient expression at low temperature in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:90–95. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.90-95.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukunaga N, Imagawa S, Sahara T, Ishii A, Suzuki M. Purification and characterization of monomeric isocitrate dehydrogenase with NADP-specificity from Vibrio parahaemolyticus Y4. J Biochem. 1992;112:849–855. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenber D, Azar I, Oppenheim A B. Differential mRNA stability of the cspA gene in the cold-shock response of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:241–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.363898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goransson M, Sonden S, Nilsson P, Dagberg B, Forsman K, Emanuelsson K, Uhlin B E. Transcriptional silencing and thermoregulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1990;344:682–685. doi: 10.1038/344682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III in DNA sequence analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:156–165. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochachka P G, Somero G N. Biochemical adaptation. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii A, Imagawa S, Fukunaga N, Sasaki S, Minowa O, Mizuno Y, Shiokawa H. Isozymes of isocitrate dehydrogenase from an obligately psychrophilic bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1: purification, and modulation of activities by growth conditions. J Biochem. 1987;102:1489–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii A, Suzuki M, Sahara T, Takada Y, Sasaki S, Fukunaga N. Genes encoding two isocitrate dehydrogenase isozymes of a psychrophilic bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6873–6880. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6873-6880.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones P G, Krah R, Tafuri S R, Wolffe A P. DNA gyrase, CS7.4, and the cold shock response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5798–5802. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5798-5802.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones P G, Inouye M. The cold shock response—a hot topic. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:811–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Teana A, Brandi A, Falconi M, Spurio R, Pon C L, Gualerzi C O. Identification of a cold shock transcriptional enhancer of the Escherichia coli gene encoding nucleoid protein H-NS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10907–10911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leyland M L, Kelly D. Purification and characterization of a monomeric isocitrate dehydrogenase with dual coenzyme specificity from the photosynthetic bacterium, Rhodomicrobium vannielii. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyazaki K, Eguchi H, Yamagishi A, Wakagi T, Oshima T. Molecular cloning of the isocitrate dehydrogenase gene of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus HB8. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:93–98. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.93-98.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muro-Pastor M I, Florencio F J. NADP+-isocitrate dehydrogenase from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120: purification and characterization of the enzyme and cloning, sequencing, and disruption of the icd gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2718–2726. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2718-2726.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture media for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–749. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochiai T, Fukunaga N, Sasaki S. Purification and some properties of two NADP-specific isocitrate dehydrogenases from an obligately psychrophilic marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1. J Biochem. 1979;86:377–384. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qoronfleh M W, Debouck C, Keller J. Identification and characterization of novel low-temperature-inducible promoters of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7902–7909. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.7902-7909.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg M, Court D. Regulatory sequences involved in the promotion and termination of RNA transcription. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:319–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki M, Sahara T, Tsuruha J, Takada Y, Fukunaga N. Differential expression in Escherichia coli of the Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 icdI and icdII genes encoding structurally different isocitrate dehydrogenase isozymes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2138–2142. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2138-2142.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takada Y, Ochiai T, Okuyama H, Nishi K, Sasaki S. An obligately psychrophilic bacterium isolated on the Hokkaido coast. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1979;25:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorsness P E, Koshland D E., Jr Inactivation of isocitrate dehydrogenase by phosphorylation is mediated by the negative charge of the phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10422–10425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh P J, Somero G N. Temperature adaptation in sea anemones: physiological and biochemical variability in geographically separate populations of Metridium senile. Mar Biol. 1981;62:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yumoto I, Kawasaki K, Iwata H, Matsuyama H, Okuyama H. Assignment of Vibrio sp. strain ABE-1 to Colwellia maris sp. nov., a new psychrophilic bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1357–1362. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]