Abstract

A 4.8-kb plasmid region carrying the four genes mcjABCD necessary for production of and immunity to the cyclic peptide antibiotic microcin J25 (MccJ25) has been sequenced. mcjA encodes the primary structure of MccJ25 as a precursor endowed with an N-terminal extension of 37 amino acids. The products of mcjB and mcjC are thought to be involved in microcin maturation, which implies cleavage of McjA and head-tail linkage of the 21-residue pro-MccJ25. The predicted McjD polypeptide, which is highly similar to several ABC exporters, was found to be required for MccJ25 secretion, thus explaining its ability to confer immunity to MccJ25.

Microcin J25 (MccJ25) is a plasmid-encoded, hydrophobic cyclic peptide consisting of 21 unmodified amino acid residues (2) which is synthesized and secreted into the culture medium by Escherichia coli AY25 isolated from human feces (15). MccJ25 is active on gram-negative bacteria, and some pathogenic species of Salmonella and Shigella are highly sensitive to it. MccJ25 exhibits a unique mode of action. It induces cell filamentation in a non-SOS-dependent way, suggesting that its molecular target may be a factor involved in cell septation (15). Thus, in addition to its interest as an antibacterial compound, MccJ25 holds promise as a tool for cell division studies. The production of MccJ25 is induced at the onset of stationary growth phase and is optimal in iron-depleted medium (15, 17). Genetic studies identified three genes, mcjA, mcjB, and mcjC, which were essential to microcin production, and one gene, mcjD, that conferred immunity to exogenous MccJ25. The four genes were located in a continuous 4.8-kb region of the 50-kb plasmid pTUC100 isolated from the AY25 strain (21). In the present study, both strands of this DNA fragment were entirely sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method of Sanger et al. (19). We show that the four genes mcjABCD are required and sufficient to confer on a bacterial host the ability to produce mature extracellular microcin. Based upon the results of physiological experiments and features of the predicted polypeptide gene products, we propose a function for each gene.

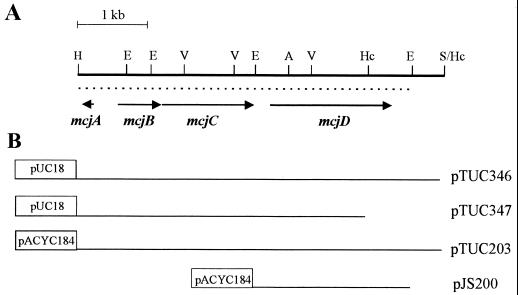

E. coli K-12 RYC1000 (F− araD139 ΔlacU169 ribΔ7 rpsL relA thiA recA56 gyrA) (6) was used as the host strain for plasmids, except when otherwise indicated. SBG231 is a MccJ25-resistant spontaneous mutant derived from strain AB259 (supQ80 λ− relA1 spoT1 thi-1), kindly provided by B. Bachmann (E. coli Genetic Stock Center). Plasmids pTUC203 and pJS200 are described in reference 21. Plasmid pTUC346, which was used for sequencing, was constructed by subcloning the HindIII-SalI fragment containing the microcin genes (Fig. 1) into pUC18. A schematic diagram of all plasmids used in this work is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

(A) Genetic organization of the HindIII-SalI fragment containing the MccJ25 system. The dotted line below the restriction map shows the sequenced region. Arrows indicate the extension and transcriptional direction of the genes identified by nucleotide sequence analysis. Abbreviations for restriction endonuclease sites: H, HindIII; E, EcoRI; V, EcoRV; A, AccI; Hc, HincII; S, SalI. (B) Map of the different plasmids used in this study. The names of the plasmids are indicated on the right. The lines correspond to the DNA of the HindIII-SalI fragment present on each construct. Boxes represent vector DNA (not drawn to scale).

The analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed the presence of four open reading frames (ORFs), which were preceded by putative ribosome binding sites at a distance adequate to initiate translation (20). The size and location of these ORFs corresponded to the four genes previously deduced from genetic complementation experiments (21). The mcjB, mcjC, and mcjD genes are transcribed in the same direction, while mcjA is transcribed in the opposite direction, diverging from mcjB (Fig. 1). The features of the predicted gene products are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of ORFs of the MccJ25 cluster

| Protein | Gene size (bp) | Predicted protein size

|

Calculated pI | Localization of protein on membranea | Homologyb | Proposed function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | kDa | ||||||

| McjA | 174 | 58 | 6.2 | 10.86 | No | No | MccJ25 precursor |

| McjB | 624 | 208 | 24.6 | 7.98 | No | No | MccJ25 maturation |

| McjC | 1,326 | 442 | 50.4 | 6.19 | No | No | MccJ25 maturation |

| McjD | 1,740 | 580 | 65.4 | 8.16 | Yes | ABC exporters | MccJ25 export |

mcjA encodes the MccJ25 precursor.

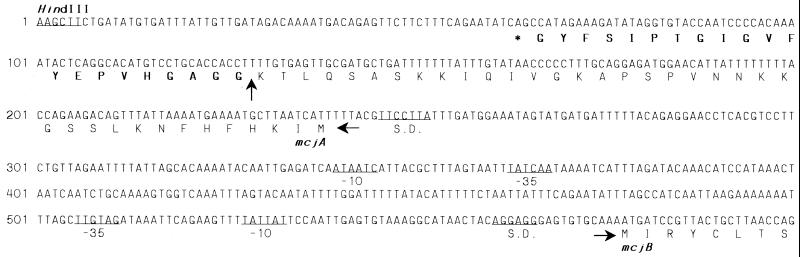

For convenience, the nucleotide sequence of mcjA is presented here (Fig. 2). The deduced amino acid sequence of the 21-residue C-terminal portion of the McjA polypeptide (from Gly-38 to Gly-58) is identical to that of purified mature MccJ25 (2). This indicates that MccJ25 derives from McjA by the elimination of the 37-residue N-peptide and subsequent head-tail linkage of the 21-residue C-propeptide. Then, as with most small-peptide antibiotics, MccJ25 is synthesized on ribosomes as a precursor (the prepropeptide) containing an N-terminal extension (the leader peptide), which is removed during peptide maturation (4, 7, 10). In the case of McjA, the cleavage should occur between Lys-37 and Gly-38. This 37-amino-acid leader peptide differs from typical secretion signal sequences of polypeptides that are secreted from the cytoplasm using the sec apparatus, suggesting that, as with many other small peptides, MccJ25 is secreted using a dedicated export machinery, as demonstrated below.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the 5′ region of the MccJ25 cluster, including the mcjA gene and the beginning of the mcjB gene. mcjA and mcjB are transcribed from the opposite DNA strands; thus, the sequence of mcjA is the noncoding strand, and the sequence of mcjB presented here is the coding strand. The stop codon of mcjA is indicated by an asterisk. Putative ribosome binding sites (S.D.) and promoter sequences are underlined. The cleavage site in McjA is indicated by a vertical arrow between amino acids 37 and 38. The amino acid sequence of mature microcin is shown in boldface.

The mcjB and mcjC gene products are required for the conversion of McjA to MccJ25.

The end of mcjB overlaps the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of mcjC, suggesting that these genes are transcriptionally and translationally coupled (1, 3). Hydropathy profiles of the inferred amino acid sequences of McjB and McjC indicated that none of these proteins has potential membrane-spanning domains or a characteristic signal peptide, which suggests that they may be cytosolic proteins. While active MccJ25 may be extracted from cells expressing the three genes mcjABC, no active peptide was detected in cells bearing plasmids that expressed only two genes, mcjA and mcjB or mcjA and mcjC (21). Therefore, McjB and McjC must take part in MccJ25 maturation, which would imply the cleavage of pre-MccJ25 and linkage of the Gly-38 residue to the C-terminal Gly-58 residue resulting in the cyclic MccJ25. Note that no significant similarity was observed between the mcjB and mcjC products and other known proteins. It is possible that the enzymatic machinery necessary for microcin biosynthesis represents unknown types of enzymes.

The mcjD gene encodes a putative inner membrane ABC exporter which is required for MccJ25 secretion.

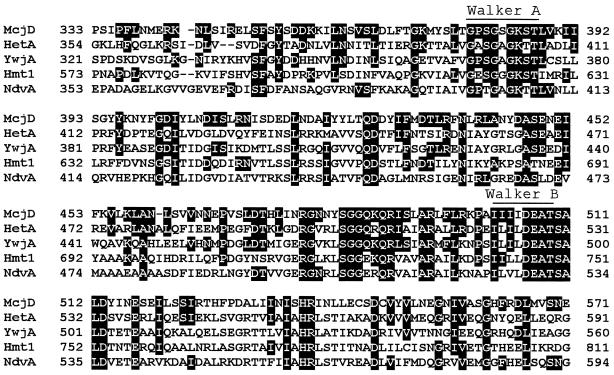

Computer-aided analysis of the amino acid sequence deduced from the mcjD gene showed that it contains all of the typical structural characteristics of known bacterial ABC exporters (5). Indeed, the amino half of McjD is predicted to span the inner membrane six times, and the carboxy half contains an ATP-binding domain, which includes the highly conserved Walker A and B motifs (23). McjD was highly similar to polypeptides belonging to the family of ABC transporter proteins. The strongest similarities were confined to the C-terminal portion of McjD surrounding the nucleotide-binding fold. Figure 3 illustrates the alignment of 240 amino acid residues of this domain for McjD and the ABC transporters that showed the highest levels of homology: HetA from Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120, required for the process of morphological differentiation of heterocysts (35% identity) (8); YwjA, a Bacillus subtilis hypothetical ABC transporter (GenBank accession no. P45861) (35% identity); Hmt1, from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, involved in heavy metal tolerance (29% identity) (14); and Rhizobium meliloti NdvA, required for β-(1→2) glucan production (27% identity) (22).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the McjD amino acid sequence flanking the nucleotide binding site with corresponding regions of other ABC transporters. The proteins listed are described in the text. Identical residues are shaded. Dashes indicate gaps introduced in the sequence to maximize the similarity. Amino acid sequences corresponding to the Walker A and B motifs (23) are indicated.

Plasmid pTUC203 contains the four genes mcjABCD (Fig. 1). When it was mutagenized with transposon Tn5, many insertion mutations impairing microcin production were obtained in genes mcjABC, but none was isolated within mcjD (21). This suggested that inactivation of mcjD could be lethal for cells expressing the other three genes; in other words, the activity of the latter would result in the biosynthesis of a toxic compound (i.e., microcin) which, in the absence of McjD, would probably accumulate in the cells and kill them. Hence, McjD could be the component or a component of the pump that extrudes MccJ25 out of producing cells. This view is consistent with the findings that McjD confers resistance (immunity) to exogenous microcin (21), and its predicted sequence displays all of the typical characteristics of an ABC exporter, as indicated above. To confirm this hypothesis, a HincII fragment was deleted from pTUC346 (MccJ25+ Imm+ Apr) to generate pTUC347 (Fig. 1). This deletion removed the nucleotide sequence that encodes the 117 amino acid residues of the C-terminal end of McjD, including the Walker B motif, but did not touch mcjABC, which remained intact. Since this construct was expected to kill nonimmune host cells, the digested and religated mixture was transformed into immune RYC1000 (pJS200 Tcr) cells, selecting for ampicillin resistance. One of the several clones obtained was shown to contain both plasmids species, the residing pJS200 and the newly constructed pTUC347. This plasmid mix was then used to transform RYC1000 cells, selecting for ampicillin or tetracycline resistance. Whereas all of the Apr transformants were also Tcr, only some of the Tcr clones were Apr. This expected result indicated that pTUC347 could not be propagated in the absence of pJS200 and supported the hypothesis that the compound synthesized from pTUC347 was lethal in the absence of McjD.

While the above experiments were in progress, we simultaneously conducted a search for new types of MccJ25-resistant mutants. Although most of the clones isolated belonged to the already-known classes of resistant mutants (i.e., sbmA, tonB, exb, and fhuA mutants [16, 18]), one of them showed a distinct phenotype. Presuming that this mutant (called SBG231) was a microcin target mutant, we transformed it with a plasmid preparation containing both pTUC347 and pJS200, selecting for ampicillin resistance. This time, clones harboring only pTUC347 were obtained. These transformants (Apr Tcs) grew normally, indicating that the chromosomal mutation overcame the inhibitory effect of pTUC347, but they were unable to give growth inhibition halos on microcin-sensitive indicator strains. When these nonproducing cells were checked for intracellular antibiotic activity, we found that they contained as much microcin as SBG231(pTUC346) cells. The extracted antibiotic killed MccJ25-susceptible cells but had no effect on MccJ25-immune and MccJ25-resistant mutant cells (SBG231), indicating that it was true mature microcin. On the other hand, when transformed with pJS200, which contains only the mcjD gene, strain SBG231(pTUC347) gained the ability to produce normal-sized inhibition halos on MccJ25-sensitive cells. Together, these results indicated that McjD is not involved in MccJ25 synthesis and maturation but is required for its export out of the producing cells.

Concluding remarks.

In this study, we have presented the molecular characterization of the four plasmid genes, mcjABCD, involved in microcin production. No other ORF with potential biological significance was detected in the nucleotide sequence. Our results indicate that MccJ25 derives from McjA by elimination of a 37-residue leader peptide and subsequent cyclization of the 21-residue C-terminal propeptide. The dipeptide Gly-38–Gly-39, adjacent to the cleavage site (Fig. 2), is reminiscent of the double glycine motif found in the leader peptides of most nonlantibiotics and some lantibiotic peptides from gram-positive bacteria and colicin V from E. coli (4, 10). However, apart from this, the MccJ25 leader did not share significant homology with consensus sequences found in the double-glycine-type leader peptides. Furthermore, in the latter the cleavage occurs at the carboxy side of the Gly-Gly motif whereas the microcin leader is cleaved just prior to the glycine residues. Another feature distinguishing the MccJ25 leader from those of the Gly-Gly class is the net charge; whereas that of the latter ones is highly negative, the MccJ25 leader peptide is highly positive.

Although the function of McjB and McjC is not well defined, they are clearly required for microcin biogenesis. With regard to the mcjD gene product, we have demonstrated that it is necessary for endogenously synthesized MccJ25 to be exported out of the cells. The predicted location and amino acid sequence of McjD are consistent with this role. Thus, the immunity conferred by McjD could well be mediated by active efflux of the peptide, which would keep its concentration below a critical level.

Finally, it is interesting to note that posttranslational modification of ribosomally synthesized peptides by tail-head linkage is not common. In fact, MccJ25 appears to be the second example of this new type of peptide. The first one is the Enterococcus faecalis bacteriocin AS-48, whose genetic system has recently been characterized (12, 13).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the 4.8-kb region described in this work has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF061787.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) grant PID 3-013800, Fundación Antorchas grant 12576/1-000065, and funds from the Consejo de Investigaciones de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (CIUNT). J.O.S. was the recipient of a CONICET fellowship, R.N.F. was a career investigator of CONICET, and M.C. was a visiting scientist from Istituto di Biologia dello Sviluppo (C.N.R., Italy).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksoy S, Squires C L, Squires C. Translational coupling of the trpB and trpA genes in Escherichia coli tryptophan operon. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:363–367. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.363-367.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blond A, Péduzzi J, Goulard C, Chiuchiolo M J, Barthélémy M, Prigent Y, Salomón R A, Farías R N, Moreno F, Rebuffat S. The cyclic structure of microcin J25, a 21-residue peptide antibiotic from Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:747–755. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das A, Yanofsky C. A ribosome binding site sequence is necessary for efficient expression of the distal gene of a translationally-coupled gene pair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4757–4768. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.11.4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vos W M, Kuipers O P, van der Meer J R, Siezen R J. Maturation pathway of nisin and other lantibiotics: post-translationally modified antimicrobial peptides exported by Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fath M J, Kolter R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:995–1017. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.995-1017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrido M C, Herrero M, Kolter R, Moreno F. The export of the DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17 provides immunity for the host cell. EMBO J. 1988;7:1853–1862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Håvarstein L S, Diep D B, Nes I F. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland D, Wolk C P. Identification and characterization of hetA, a gene that acts early in the process of morphological differentiation of heterocysts. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3131–3137. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3131-3137.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein P, Kanehisa M, DeLisi C. The detection and classification of membrane-spanning proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;815:468–476. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolter R, Moreno F. Genetics of ribosomally synthesized peptide antibiotics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:141–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M, Gálvez A, Samyn B, van Beeumen J, Coyette J, Valdivia E. Determination of the gene sequence and the molecular structure of the enterococcal peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6334–6339. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6334-6339.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Bueno M, Valdivia E, Gálvez A, Coyette J, Maqueda M. Analysis of the gene cluster involved in production and immunity of the peptide antibiotic AS-48 in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:347–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortiz D F, Kreppel L, Speiser D M, Scheel G, McDonald G, Ow D W. Heavy metal tolerance in the fission yeast requires an ATP-binding cassette-type vacuolar membrane transporter. EMBO J. 1992;11:3491–3499. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salomón R A, Farías R N. Microcin 25, a novel antimicrobial peptide produced by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7428–7435. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7428-7435.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salomón R A, Farías R N. The FhuA protein is involved in microcin 25 uptake. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7741–7742. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7741-7742.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salomón R A, Farías R N. Influence of iron on microcin 25 production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salomón R A, Farías R N. The peptide antibiotic microcin 25 is imported through the TonB pathway and the SbmA protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3323–3325. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3323-3325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solbiati J O, Ciaccio M, Farías R N, Salomón R A. Genetic analysis of plasmid determinants for microcin J25 production and immunity. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3661–3663. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3661-3663.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanfield S W, Ielpi L, O’Brochta D, Helinski D R, Ditta G S. The ndvA gene product of Rhizobium meliloti is required for β-(1→2)glucan production and has homology to the ATP-binding export protein HlyB. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3523–3530. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3523-3530.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases, and other ATP requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]