Abstract

Phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays a key role in stomata closure, osmostress acclimation, and vegetative and embryonic dormancy. Group B3 Raf protein kinases (B3-Rafs) serve as positive regulators of ABA and osmostress signaling in the moss Physcomitrium patens and the angiosperm Arabidopsis thaliana. While P. patens has a single B3-Raf called ARK, specific members of B3-Rafs among six paralogs regulate ABA and osmostress signaling in A. thaliana, indicating functional diversification of B3-Rafs in angiosperms. However, we found that the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha, belonging to another class of bryophytes, has three paralogs of B3-Rafs, MpARK1, MpARK2, and MpARK3, with structural variations in the regulatory domains of the polypeptides. By reporter assays of the P. patens ark line and analysis of genome-editing lines of M. polymorpha, we found that these B3-Rafs are functionally redundant in ABA response, with respect to inhibition of growth, tolerance to desiccation and expression of stress-associated transcripts, the majority of which are under the control of the PYR/PYL/RCAR-like receptor MpPYL1. Interestingly, gemmae in gemma cups were germinating only in mutant lines associated with MpARK1, indicating that dormancy in the gametophyte is controlled by a specific B3-Raf paralog. These results indicated not only conservation of the role of B3-Rafs in ABA and osmostress response in liverworts but also functional diversification of B3-Rafs, which is likely to have occurred in the early stages of land plant evolution.

Keywords: abscisic acid, liverworts, vegetative dormancy, genome editing, Raf kinase, RNA-seq, Marchantia polymorpha

Introduction

The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) produced upon sensing osmostress caused by decreases in water potential provokes various biochemical changes for protection of tissues from a forthcoming cellular dehydration that might cause severe damage to plant cells (Finkelstein et al., 2002; Sah et al., 2016). In addition to its role in stomata closure, ABA plays a role in the regulation of developmental processes of seeds, including maturation, storage protein accumulation, desiccation tolerance, and dormancy (Kermode, 2005; Ali et al., 2022). ABA is also responsible for maintenance of dormancy in vegetative tissues such as propagules, axillary buds and underground bulbs of perennials (Pan et al., 2021).

Signal transduction of ABA is initiated by the actions of “core signaling components” with the ABA receptor PYR/PYL/RCAR, group A protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C-A), and subgroup III Snf1-related protein kinase2 (SnRK2) as revealed by studies of Arabidopsis (Cutler et al., 2010). PP2C-A blocks the activity of SnRK2 under unstressed conditions, while under a water stress condition, synthesized ABA binds to PYR/PYL/RCAR to inhibit activity of PP2C-A, which results in activation of SnRK2 (Fujii et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Umezawa et al., 2009). The activated SnRK2 in turn phosphorylates ion channels and transcription factors to provoke ABA-specific cellular responses such as closure of stomata and expression of a number of stress-associated transcripts. SnRK2 is thought to be also important for the ABA-regulated dormancy of immature seeds, because a lack of the genes for SnRK2 results in precocious germination in the Arabidopsis silique (Fujita et al., 2009).

ABA serves as a phytohormone not only in angiosperms but also in bryophytes with a gametophyte-dominant life cycle. ABA induces growth secession and freezing and desiccation tolerance and also the formation of vegetative propagules called brood cells in the moss Physcomitrium patens (formerly known as Physcomitrella patens; Cuming, 2009). Disruption of PP2C-A in the ppabi1a/b double mutant caused constitutive desiccation tolerance with enhanced SnRK2 activity, and disruption of SnRK2 in the ppsnrk2a/b/c/d quadruple mutant abolished ABA and osmostress responses, indicating the conservation of core signaling mechanisms in the moss (Komatsu et al., 2013; Shinozawa et al., 2019). ABA also plays a role in stress tolerance in liverworts representing another clade of bryophytes. ABA induces desiccation tolerance in the thallus (gametophyte) of Riccia fluitans and Pallavicinia lyellii (Pence et al., 2005). In the model liverwort M. polymorpha, the gemma, a propagule for asexual reproduction, acquires desiccation tolerance by ABA in the presence of sucrose (Akter et al., 2014). We reported that the M. polymorpha MpABI1 gene encoding PP2C-A functions as a negative regulator of ABA signaling (Tougane et al., 2010). Furthermore, the disruptant of the MpPYL1 gene encoding a PYR/PYL/RCAR-like ABA receptor exhibited strong ABA insensitivity with reduced desiccation tolerance in gemmae (Jahan et al., 2019). Considering that bryophytes are the evolutionarily earliest diverging group of land plants, conservation of the core signaling components of ABA for stress tolerance suggests that acquisition of these components had been crucial for the colonization of land by the common ancestor of land plants (Bowman et al., 2017; Komatsu et al., 2020).

A recent report also indicates that ABA possibly controls dormancy of gemmae in gemma cups in M. polymorpha. Gemmae stay dormant as long as they sit inside the gemma cups formed on thalli but grow rhizoids when the gemmae are placed under growth-favorable conditions outside the gemma cups. ABA treatment of M. polymorpha gemmae delays rhizoid initiation in a dose-dependent manner (Eklund et al., 2018). Furthermore, the disruptant of MpABI3A, an ortholog of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 of Arabidopsis, bore gemmae growing rhizoids in the gemma cups, indicating that the mechanism of dormancy maintained by ABA might be common in liverworts and seed plants (Eklund et al., 2018).

In addition to core signaling components for ABA discovered in angiosperms, our study using P. patens revealed that ARK belonging to the group B3 Raf protein kinases (B3-Rafs) is crucial for activation of SnRK2 (Saruhashi et al., 2015). An ark mutant designated AR7 showed little response to ABA, cold and hyperosmotic stress, indicating that ARK plays a role in the integration of environmental abiotic signals. AR7 had little SnRK2 activity upon treatment with ABA, cold and hyperosmosis, and a recombinant protein of the ARK kinase domain phosphorylated conserved serine residues in the activation loop of SnRK2 (Saruhashi et al., 2015; Shinozawa et al., 2019). Disruption of ARK in the ppabi1a/b mutant abolished SnRK2 activity and ABA-induced gene expression, indicating that ARK is a crucial positive regulator of SnRK2 in ABA and abiotic stress signaling (Islam et al., 2021). Reporter assays of P. patens indicated that genes of three of the six B3-Rafs of Arabidopsis designated AtARK1, AtARK2, and AtARK3 can complement the ark phenotype (Saruhashi et al., 2015). Disruption of these B3-Rafs in A. thaliana resulted in reductions in SnRK2 activity and osmostress response (Katsuta et al., 2020). Our study and studies done by other researchers indicated that the function of B3-Raf as an activator of SnRK2 is conserved in angiosperms (Lin et al., 2020; Takahashi et al., 2020). In addition to B3-Rafs, Arabidopsis genome has six genes for group B2 Raf kinases (B2-Rafs), which have the “PAS domain” that facilitates protein–protein interactions in the N-terminal non-kinase region, and it was shown that the PAS domain is important for dimerization of B2-Rafs (Lee et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2019). Disruption of B2-Rafs (RAF10 and RAF11) in Arabidopsis caused loss of ABA response in seed germination, indicating that these kinases might provide an additional mechanism of ABA response in seeds (Nguyen et al., 2019).

In contrast to the P. patens genome that has a single gene for B3-Raf (ARK) and no B2-Raf genes, we found that the genome of M. polymorpha has multiple genes for B3-Raf and B2-Raf as does Arabidopsis. However, the role of these Raf kinases in liverworts has not been determined. In this study, we generated mutants of group B2-Raf and B3-Raf in M. polymorpha by genome editing and analyzed growth and stress responses to ABA. Analyses of the mutant lines revealed differential roles of Raf kinase isoforms in desiccation tolerance and vegetative dormancy in the liverwort.

Materials and methods

Culture of plant materials

Male gametophyte of M. polymorpha accession Takaragaike-1 (TAK-1) was cultured by planting gemmae on a half-strength B5 agar medium with 1% sucrose (Akter et al., 2014). Protonemata of the P. patens for reporter assays were cultured on a cellophane-overlaid BCDAT agar medium (Bhyan et al., 2012).

Generation of CRISPR Cas-9 genome editing line

For constructs for genome editing lines, double-strand oligonucleotides containing the target guide RNA sequence were fused downstream to the U6 promoter (Sugano et al., 2018) in the pMpGE010 vector containing the Cas9 gene and a hygromycin phosphotransferase gene cassette. For making double mutants, similar constructs were made using pMpGE011, with a mutated acetolactate synthase gene for chlorsufuron-resistance was used (Ishizaki et al., 2015). Agrobacterium (Rhizobium radiobacter) C58 strain harboring the above constructs was used for infection of cultured gemmalings of M. polymorpha as described by Kubota et al. (2013). After selection on a medium containing 10 mg L−1 hygromycin or 0.5 μM chlorsulfuron, gemmae of the generated transgenic lines were individually cultured for further experiments.

Reporter assays

The cDNA encoding Raf kinases was fused downstream to the rice actin promoter and used for transient reporter assays. The constructs were introduced into protonema cells of the ARK-null AR133 mutant of P. patens, in which the CGA codon of Arg1043 has been changed to TGA, with the proEm-GUS reporter construct (Marcotte et al., 1989) and the proUbi-LUC reference construct (Christensen and Quail, 1996) by particle bombardment using the PDS-1000He particle delivery system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After bombardment, the protonema cells were cultured at 25°C under continuous light for 1 day on a BCDAT medium with or without 10 μM ABA. Proteins extracted from the protonemata were used for GUS and LUC assays to determine GUS/LUC ratio as previously described (Komatsu et al., 2009).

Determination of gemma dormancy

Gemmae isolated from gemma cups located at the most basal position in thalli were stained by 15 μM propidium iodide and 0.01% Triton X-100 for 15 min and observed under the binocular fluorescent microscope (Leica M205FA, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) using the DsRED filter set. The number of gemmae with elongated rhizoids were counted. A total of 60–114 gemmae were used for each data point of three biological replicates.

Tests for desiccation tolerance

Gemmae were cultured for 1 day in a half-strength B5 liquid medium with or without 1 and 10 μM ABA and transferred onto a sheet of cellophane on wet filter paper in a petri dish. The dish was then placed in an airtight container containing silica gel and kept at 23°C for 2 days in the dark for desiccation treatment. The dried gemmae on the cellophane were rehydrated by immersing in the same liquid medium, and then transferred onto a fresh agar medium and cultured for 10 days to determine survival (Jahan et al., 2019).

Total RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription (qRT-PCR) analysis

Gemmalings cultured for 4 days in liquid medium were treated with or without 10 μM ABA for 6 h for RNA extraction. qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using oligonucleotides for MpLEAL1 (Mapoly0112s0030, Mp4g09300), MpLEAL3 (Mapoly0035s0082, Mp6g02960), MpLEAL5 (Mapoly0087s0015, Mp4g05760), MpLEAL6 (Mapoly0027s0114, Mp5g05120), and MpABI3 (Mapoly0086s0035, Mp5g08310; Supplementary Table S1). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The ABA-unaffected MpEF1 (Mapoly0024s0116, Mp3g23400; Ishizaki et al., 2008) was used for normalization.

RNA-seq analysis

Quality of total RNA extracted from WT and mutants was confirmed by Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). RNA libraries were prepared using 1 μg of total RNA according to the protocol of the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States). The library size was 200–700 bp as measures by Bioanalyzer 2100, and the average length of the library was 350 bp. The library concentration was measured by Kapa Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, United States) and adjusted to 10 nM. Sequencing of the library was performed on the Hiseq 2500 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Conversion of single reads to FASTQ format was performed by bcl2fastq tool version 2.18.0.12 (Illumina). Row read data for each library were stored in the DDBJ (accession number DRA014012). Trimming of the reads, mapping to the M. polymorpha genome v3.1 (Phytozome 12)1 and extraction of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were performed using CLC genomics workbench version 12 (Qiagen). In trimming, the following parameters were changed (quality limit = 0.001, number of 5′ terminal nucleotides = 14, number of 3′ terminal nucleotides = 3, and minimum number of nucleotides in reads = 36). Genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05 and a fold change greater than 2 were defined as DEGs.

Results

Characterization of group B2/B3 Raf genes and transient assays in Physcomitrium patens

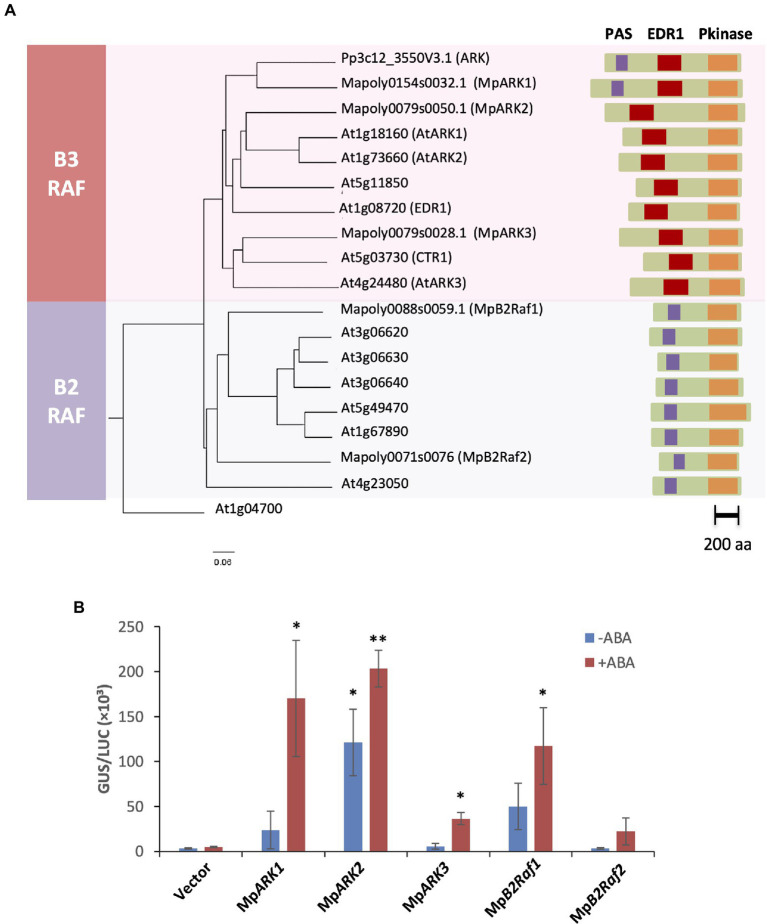

By a BLAST search of the M. polymorpha genome database, we identified one gene (Mapoly0154s0032, Mp8g16320) encoding 1,294 amino acids with the highest similarity to P. patens ARK. The gene was designated M. polymorpha ARK1 (MpARK1). A search of the Pfam database revealed that, as in the case of P. patens ARK, the MpARK1 polypeptide has a PAS domain (amino acids 178–290) toward the N-terminus, a protein kinase domain (amino acids 1019–1266) near the C-terminus and a conserved EDR1 domain (amino acids 585–788) between these domains (Figure 1A). In addition, two other genes for B3-Rafs related to MpARK1 were found in the M. polymorpha genome, and these genes were designated as MpARK2 (Mapoly0079s0050, Mp8g15630) and MpARK3 (Mapoly0079s0028, Mp8g15840). The polypeptides encoded by these genes had both the EDR1 and C-terminal kinase domains but lacked obvious PAS domains.

Figure 1.

(A) Phylogenetic relationships and polypeptide structures of group B2 and B3 Raf kinases. The phylogenetic analysis was conducted by the neighbor-joining method using CLASTALW. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap values (100 replicates) and the bar represents the number of amino acid changes per branch length. (B) Reporter assays of ark mutant of P. patens using cDNA constructs of group B2 and B3 Raf kinases of M. polymorpha. The constructs of cDNA fused to the rice actin promoter, proEm-GUS and proUbi-LUC were introduced into protonema cells by particle bombardment. The vector without cDNA was used as a control. The bombarded cells were cultured for 1 day with or without 10-μM ABA before GUS and LUC assays. Levels of gene expression are represented by GUS/LUC ratio. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 in the t-test (n = 3) compared with WT of the same treatment.

To determine whether MpARK1, MpARK2, and MpARK3 function in ABA responses, reporter assays were carried out using a P. patens mutant lacking ARK. cDNA fused to the rice actin promoter was introduced into protonema cells of the ARK-null AR133 mutant of P. patens, with constructs of the β-glucuronidase gene fused with the ABA-inducible wheat Em promoter as a reporter (proEm-GUS) and the firefly luciferase gene fused with the rice ubiquitin promoter (proUbi-LUC) as an ABA-nonresponsive reference. The assays revealed that the level of ABA-induced GUS expression was very low in AR133 but that the expression was restored by the introduction of MpARK1 and MpARK2 and to a lesser extent, by the introduction of MpARK3 (Figure 1B).

We also found that the M. polymorpha genome has two group B2-Raf genes, which were designated MpB2Raf1 (Mapoly0088s0059, Mp7g02280) and MpB2Raf2 (Mapoly0071s0076, Mp5g15330). Polypeptide structures of these kinases were similar to those of Arabidopsis B2-Rafs, i.e., they had the C-terminus protein kinase domain and the N-terminus PAS domain but lacked the EDR1 domain in between (Figure 1A). Transient expression of these genes in the P. patens AR133 mutant indicated that these kinases also restored the ABA-induced gene expression, with a greater effect of MpB2Raf1 compared with MpB2Raf2 (Figure 1B).

Analysis of ABA responses in genome-editing lines of group B3-Raf genes

To determine the role of B3-Rafs in M. polymorpha, we transformed a male wild-type line (WT) using genome-editing constructs targeting MpARK1, MpARK2, and MpARK3 to generate mutant lines. The 18-nucleotide target sequences were designed in the kinase domain of each gene and fused between the MpU6 promoter and the gRNA backbone sequence in the MpGE10 vector carrying a hygromycin resistant marker. By Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, we obtained Mpark1ge, Mpark2ge, and Mpark3ge mutant lines (Supplementary Figure S1). When gemmae of these lines were planted on a medium containing ABA, all of the lines showed reduced growth sensitivity to ABA at 1 μM in comparison with WT. However, these single mutant lines retained sensitivity to a higher concentration (10 μM) of ABA (Supplementary Figure S2).

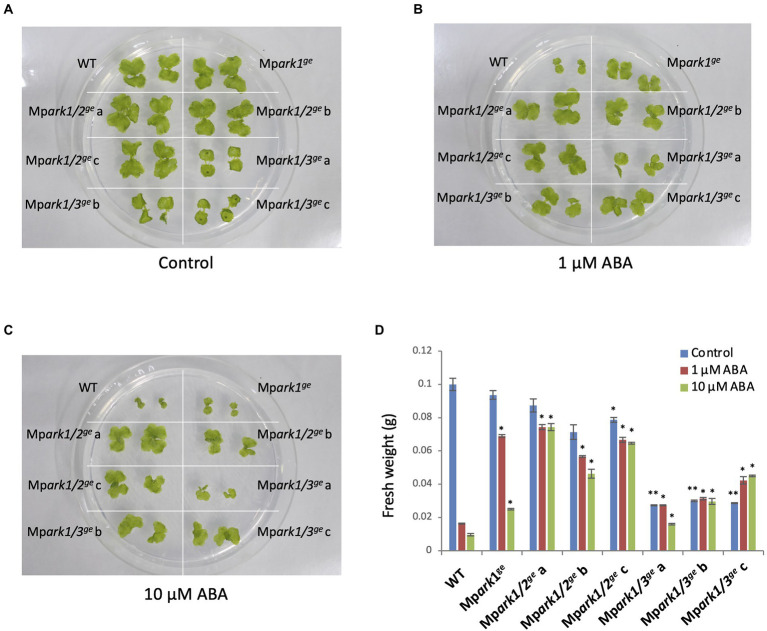

Thus, we made double mutant lines by transforming the Mpark1ge line using the MpGE11 vector carrying a chlorsulfuron-resistance marker gene and obtained Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge lines (Supplementary Figure S1). When gemmae of three independent lines of both mutants were grown on media containing 1 and 10 μM ABA, the plants were resistant to 10 μM ABA (Figure 2), although some growth retardation with or without ABA was observed in the Mpark1/3ge lines. These results indicated that B3-Rafs play a role in ABA responses in gemmalings of M. polymorpha. We also obtained both single and double mutants of MpB2Raf1 and MpB2Raf2 by genome editing (Supplementary Figure S3a). Growth analysis of gemmae of these lines, however, indicated that their ABA response was similar to that of WT (Supplementary Figure S3b).

Figure 2.

Effect of ABA on growth of gametophytes of M. polymorpha. Gemmae of wild type (WT) and three each of double mutant lines of MpARK1 and MpARK2 (Mpark1/2gea to c) and MpARK1 and MpARK3 (Mpark1/3gea to c) were grown on medium without ABA (control) (A) or with 1-μM (B) or 10-μM (C) ABA for 14 days. (D) Fresh weight of the gemmalings was plotted in histograms. Error bars indicate the standard error (n = 3). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 in the t-test compared with WT of the same treatment.

Vegetative dormancy and desiccation tolerance in the B3-Raf genome-editing lines

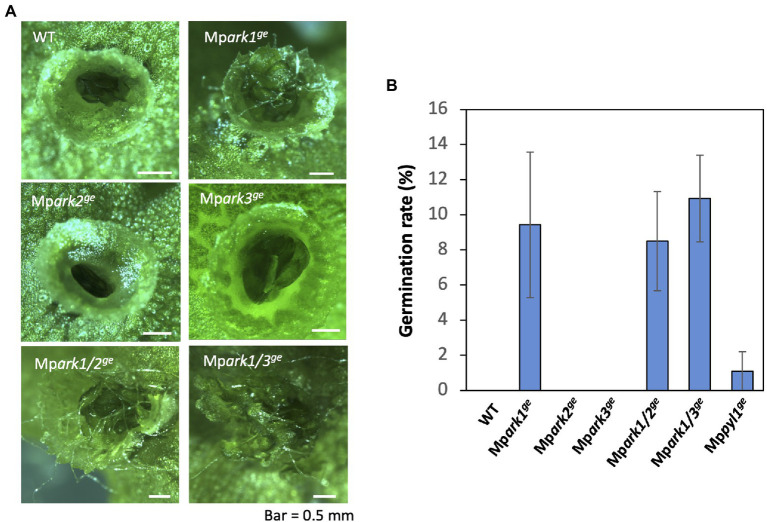

Our observations of the generated genome-editing lines indicated that many gemma germinate to form rhizoids in gemma cups in Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge but not in WT, Mpark2ge and Mpark3ge (Figure 3A). Counting the number of gemmae growing rhizoids in gemma cups revealed that germination rates of Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2g,e and Mpark1/3ge were similar (Figure 3B), while there was no germination of gemmae at a similar growth stage in WT, Mpark2ge and Mpark3ge. We compared the germination rates of these genome-editing lines with the germination rate of Mppyl1ge lacking the major PYR/PYL/RCAR in gametophytes (Jahan et al., 2019), which shows strong ABA insensitivity. Interestingly, the germination rate of the gemmae of Mppyl1ge was greater than that of WT but much less than that of Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge (Figure 3B; Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of dormancy of gemmae in gemma cups. (A) Appearance of gemmae in a gemma cup of WT and the B3-Raf genome-editing lines of M. polymorpha. Germination of rhizoids was frequently observed in gemmae of Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge lines while gemmae of WT and Mpark2ge and Mpark3ge remained dormant within the gemma cup. (B) Germination rate of gemmae in gemma cup of WT and genome editing lines. Gemmae isolated from a gemma cup located at the most basal position in the thallus were used for analysis. Germination of rhizoids from gemmae was analyzed by staining with propidium iodide, and the percentages of gemmae growing rhizoids were plotted in histograms. The experiment was carried out on a date different from that shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Error bars indicate +/− SE of the mean (n = 3).

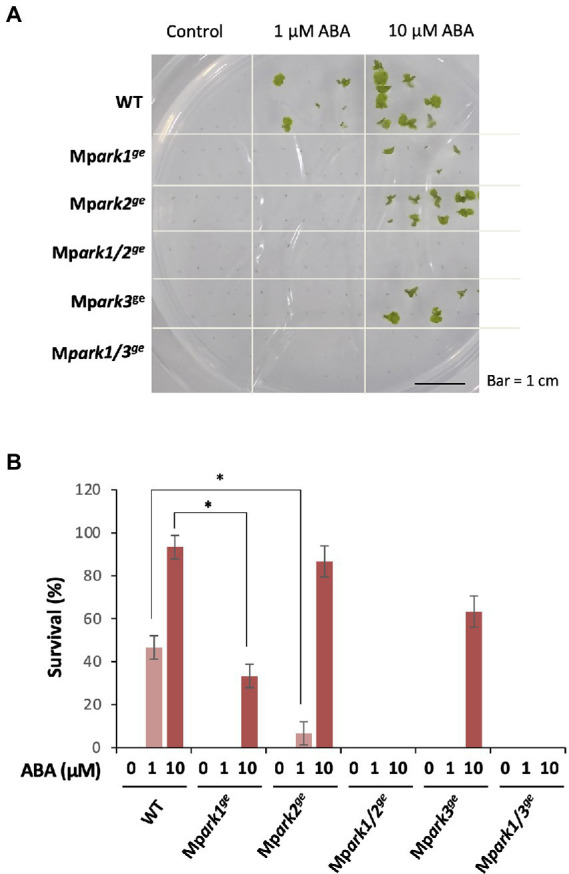

We also examined desiccation tolerance in the gemmae of WT and the mutant lines. Gemmae of these plants were incubated with or without 1 and 10 μM ABA for 1 day and dried for 2 days in a chamber containing dried silica gel. Determination of survival by rehydration and reculture on a fresh medium revealed that all mutant lines showed reduced desiccation tolerance in comparison with that of WT (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figure S5), i.e., survival was enhanced by 1 and 10 μM ABA in WT as we reported previously (Jahan et al., 2019), but it was not enhanced by 1 μM ABA in the single mutants Mpark1ge, Mpark2ge, and Mpark3ge and even by 10 μM ABA in the Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge double mutants (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of ABA on desiccation tolerance in M. polymorpha. Gemmae of wild type (WT) and the B3-Raf genome-editing lines were cultured for 1 day with or without 1 or 10 μM ABA in liquid medium. The gemmae were transferred to a container containing silica gel and dried for 2 days. After rehydration, the gemmae were transferred onto a fresh agar medium and cultured for 10 days to determine survival. (A) Growth appearance of gemmalings after culture for 10 days. (B) Survival rate was plotted in histograms. Error bars indicate +/− SE. *p < 0.05 by t-test (n = 3).

RNA-seq analysis of genome-editing lines

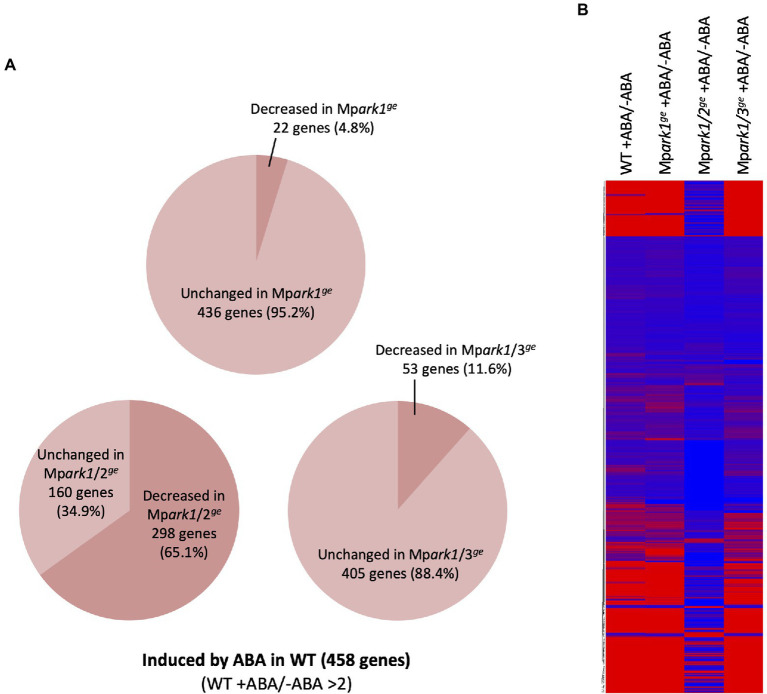

To reveal global changes in gene expression controlled by B3-Rafs, we analyzed ABA-responsive transcriptomes in representative genome-editing lines. RNA-seq analysis revealed that 458 genes were induced more than two-fold by 6-h treatment with 10 μM ABA in WT. Expression of 22 (4.8%) of the genes was decreased to less than half in ABA-treated Mpark1ge compared with that in ABA-treated WT, while expression of 298 (65.1%) and 53 (11.6%) of the genes was decreased in Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge, respectively (Figure 5A; Supplementary Figure S6). A heat map of gene expression also indicated that the majority of genes induced by ABA in WT were not induced in Mpark1/2ge (Figure 5B). We also analyzed the expression of ABA-repressed genes. Of 87 ABA-repressed genes detected in WT, expression of 24 (27.5%), 57 (65.5%), and 44 (50.6%) of the genes was increased in Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge, respectively (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 5.

Profiles of ABA-responsive gene expression in wild type (WT) and the B3-Raf genome-editing lines. (A) Percentages of ABA-induced genes (>2) for which expression was reduced (<2) in the genome-editing lines. (B) Heat map showing ABA-induced and ABA-reduced genes in WT and the genome editing lines. The fold change used for the color key was calculated by comparing values of ABA-treated and control samples.

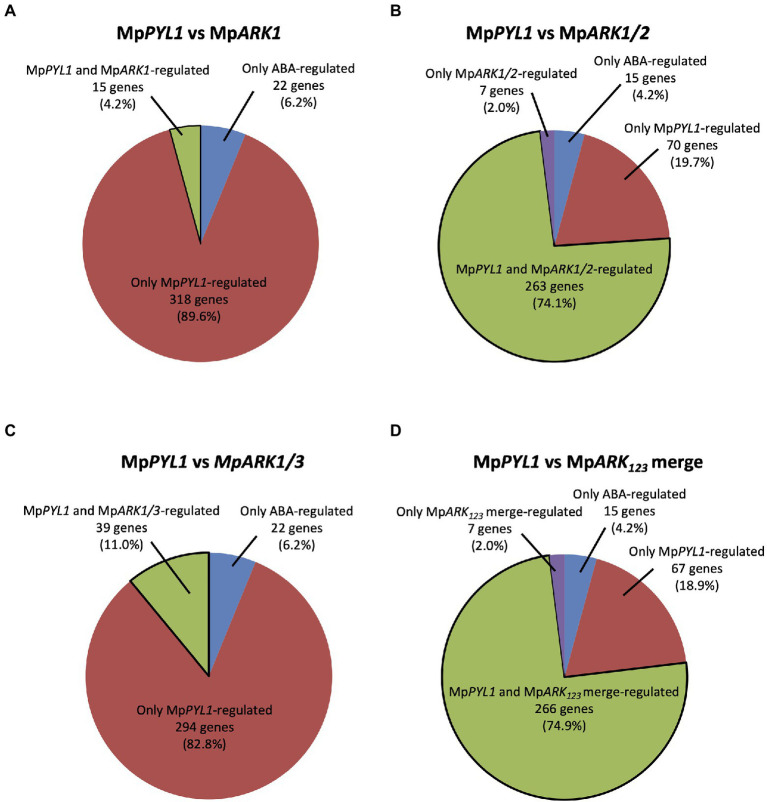

We previously showed that the expression of approximately 80% of ABA-induced genes was decreased in the Mppyl1ge mutant (Jahan et al., 2019). Reanalysis of the extracted 333 ABA-induced genes previously identified as genes regulated by MpPYL1 indicated that expression of 15 (4.5%), 263 (79.0%), and 39 (11.7%) of the genes was reduced in Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge, respectively. This corresponded to 4.2%, 74.1%, and 11.0% of ABA-induced genes commonly identified in this study and the study by Jahan et al. (2019); (Figures 6A–C). A comparison with the merge of the results of Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge indicated that the expression of 266 genes (79.9%) regulated by MpPYL1 was reduced in either of the B3-Raf mutants (Figure 6D), indicating that the majority of B3-Raf-regulated genes are under the control of MpPYL1.

Figure 6.

Relationships between ABA-induced genes mediated by the ABA receptor MpPYL1 and B3-Rafs. Using ABA-induced 355 genes commonly identified in this study and our previous study (Jahan et al., 2019), percentages of genes under the control of MpPYL1, B3-Rafs and both are analyzed. Genes for which expression in Mppyl1ge, Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge is less than half of WT are represented as MpPYL1-, MpARK1-, MpARK1/2-, and MpARK1/3-regulated genes (A–C). The result of analysis against the merge of Mpark1ge, Mpark1/2ge, and Mpark1/3ge (MpARK123 merge) is also shown (D).

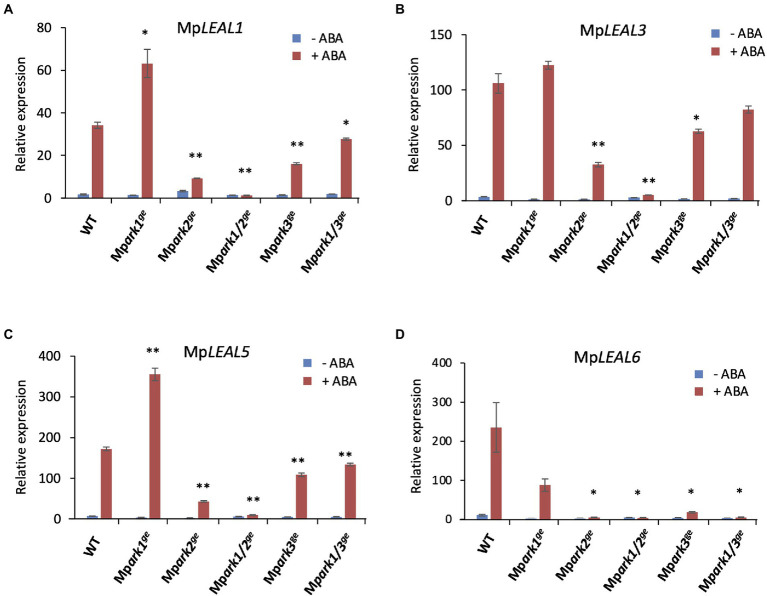

Previous studies shed light on the role of ABA-induced Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA)-like transcripts in desiccation tolerance in bryophytes (Akter et al., 2014; Hatanaka et al., 2014). LEA-like genes encoding hydrophilic proteins are thought to be important for protection from dehydration damage (Shih et al., 2008). We reported that M. polymorpha LEA-like (MpLEAL) transcripts are induced by ABA in WT but not in Mppyl1ge, which is desiccation-sensitive (Jahan et al., 2019). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for four representative MpLEAL genes revealed that ABA-induced expression of all four transcripts was very little in Mpark1/2ge in comparison with that in WT. Reductions in the expression of these MpLEAL genes to various extents were observed in Mpark2ge, Mpark3ge, and Mpark1/3ge. In contrast, there was no significant decrease in any of these MpLEAL transcripts in the Mpark1ge single mutant (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

ABA-induced expression of LEA-like genes in wild type (WT) and B3-Raf genome editing lines. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was carried out using RNA isolated from gemmalings treated with or without 10 μM ABA. Transcripts for MpLEAL1 (Mapoly0112s0030) (A), MpLEAL3 (Mapoly0035s0082) (B), MpLEAL5 (Mapoly0087s0015) (C), and MpLEAL6 (Mapoly0027s0114) (D) were analyzed. Relative values were determined by SYBR green-based quantitative PCR analysis using MpEF1 (Mapoly0024s0116) unaffected by ABA as a reference. Error bars indicate +/− SE. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by t-test (n = 3) compared with WT of the same treatment.

Discussion

Roles of B3 Raf kinases in ABA response are conserved in embryophytes

Sequencing the whole genomes of various organisms has revealed the presence of signal transduction processes for ABA in both vascular and nonvascular plants, indicating that the basic toolkit for ABA signaling has been acquired in the common ancestor of embryophytes (Rensing et al., 2008; Takezawa et al., 2011; Bowman et al., 2017). Identification of the genes for the functional ABA receptors in bryophytes, comprising the earliest divergent groups of land plants, indicates that the acquisition of the receptors might have been the key evolutionary event for the establishment of the mechanism for PP2C-A-mediated SnRK2 regulation in the common ancestor of land plants (Jahan et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Komatsu et al., 2020). Identification of B3-Raf as a positive regulator of SnRK2 has extended our understanding of the integrated regulation of ABA and osmostress signals (Saruhashi et al., 2015; Katsuta et al., 2020; Takahashi et al., 2020). In this study, we demonstrated that the function of B3-Rafs in ABA and abiotic stress response is conserved in liverworts, which are recognized as a distinct lineage of basal land plants, by reporter assays and analysis of mutant lines of M. polymorpha. ABA-induced growth retardation, gemma dormancy and desiccation tolerance are important adaptive mechanisms to survive the period of water scarcity. Reversal of phenomena by lack of B3-Rafs indicate that the B3-Rafs are important components for survival in the terrestrial environment. Taken together with the results of our previous studies showing complementation of P. patens ark mutant with B3-Raf genes of A. thaliana and the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii (Saruhashi et al., 2015), the results obtained in this study indicate that the role of B3-Rafs in stress signaling is conserved in embryophytes.

The presence of three B3-Rafs in M. polymorpha with structural variations provides new insights into the evolutionary diversity of B3-Rafs. Identification of MpARK2 and MpARK3, B3-Rafs phylogenetically related to those of Arabidopsis but absent in P. patens, suggests that B3-Raf in this clade as a positive regulator of stress signaling had been raised in basal land plants (Figure 1A). Gene expression studies have revealed that the MpARK2 disruption has a greater effect on the ABA-induced gene expression than does the MpARK3 disruption, especially when the gene was co-disrupted with MpARK1 (Figures 5, 7). In the RNA-seq data, there was a significant reduction (−5.13-fold, FDR < 0.05) in the expression of a gene (Mapoly0072s0050) encoding ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5)-like transcription factor in Mpark1/2ge but not in Mpark1/3ge. Such difference might have caused a drastic reduction in the ABA-induced gene expression in Mpark1/2ge.

MpARK1, which forms an independent B3-Raf clade with P. patens ARK (Figure 1A), might have functions in the regulation of distinct genes. Unlike Mpark2ge and Mpark3ge, Mpark1ge did not show reductions in LEA-like transcript expression but showed reductions in transcripts encoding several bryophyte-specific proteins and proteins for which functions have not been identified such as “desiccation-like protein” (Supplementary Table S2). A distinct function of MpARK1 might be attributed to the domain structures of the polypeptide. The PAS domain found only in the MpARK1/ARK-clade kinases indicates that these B3-Rafs might function as a dimer (Stevenson et al., 2016), whereas other B3-Rafs without PAS domains function as monomers. It has been shown that the PAS domain is important for dimerization of B2-Raf kinases of Arabidopsis (Nguyen et al., 2019), although the functional significance of the dimerization has not been demonstrated. Results of both reporter assays (Figure 1B) and mutant studies (Figures 2-6) indicate that MpARK2 and MpARK3 have a function redundant with that of MpARK1 with respect to the ABA response, indicating that the PAS domain may not be crucial for the ABA response. On the other hand, the EDR1 domain that is common in the B3-Raf kinases of both bryophytes and angiosperms might be important for the function of the B3-Raf molecule. In P. patens ARK, a single Ser to Phe substitution in the EDR1 domain was identified in the ABA-insensitive mutant AR7 (Saruhashi et al., 2015), indicating that a small structural change in this domain can affect the function of B3-Raf. The EDR1 domain might be important for interaction with other molecules that regulate the activity of B3-Raf. We recently reported that sensor-histidine kinases (HK) can interact with ARK and that the knockout mutants of HK showed little response to ABA and osmostress in P. patens (Toriyama et al., 2022). An N-terminal deletion of ARK to a domain adjacent to the EDR1 domain abolished the interaction with HK, whereas a deletion to the PAS domain alone did not affect interaction with HK or response to ABA (Toriyama et al., 2022). A functional comparison of B3-Raf paralogs of M. polymorpha with deletions and point mutations in the EDR1 domain would reveal the role of this domain in interaction with HK and responses to ABA/osmostress.

In this study, we also showed that M. polymorpha has B2-Rafs, which are present in angiosperms but not in P. patens. Although mutant lines of MpB2Raf1/2ge did not exhibit obvious changes in ABA response (Supplementary Figure S3), restoration of ABA-induced gene expression in the ark line (Figure 1B) indicates that B2-Rafs might also participate in the ABA response in liverworts. Arabidopsis B2-Rafs appear to be crucial for the ABA response in seeds, but their function might be different from that of B3-Rafs. While B3-Rafs phosphorylate residues in the activation loop of SnRK2 for activation, B2-Rafs phosphorylate a residue near the C-terminus, which can reduce interaction with PP2C-A that negatively regulates SnRK2 (Nguyen et al., 2019). The phosphorylation site for B2-Raf is conserved in SnRK2s of P. patens and M. polymorpha, although the mode of regulation of SnRK2 in bryophytes might be different from that in Arabidopsis as previously discussed by Komatsu et al. (2013).

Roles of B3-Raf kinase in gemma dormancy

Dormancy of vegetative organs such as axillary buds and propagules is widely recognized in land plants as a developmental strategy for survival under seasonally changing environmental conditions. The dormancy and its release are controlled by phytohormones such as auxin, cytokinins, abscisic acid, and strigolactones and also by environmental factors such as light, water status, and temperature (Lang, 1987; Horvath et al., 2003). In contrast to the well-defined roles of ABA-regulated factors such as ABI3 (Giraudat et al., 1992), AHG1/3 (Nishimura et al., 2004), and DOG1 (Bentsink et al., 2006) in seed dormancy, the molecular target of ABA for the regulation of dormancy in vegetative tissues has not been clarified. Thus, gemmae formed in gemma cups in M. polymorpha can be a useful model for genetic studies of vegetative dormancy, since the developmental processes of the gemmae might be under the control of factors common in embryophytes (Kato et al., 2020). Frequent observation of rhizoid growth in gemmae in gemma cups of Mpark1ge and the Mpark1ge-derived double mutants Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge but not in Mpark2ge and Mpark3ge single mutants indicates that MpARK1 plays a specific role in dormancy in gemmae (Figure 3). A higher germination rate observed in Mpark1ge than in Mppyl1ge might indicate that the effect of MpARK1 on gemma dormancy includes an ABA-independent process. This notion is consistent with the results of RNA-seq analysis showing a limited correlation between MpARK1- and MpPYL1-regulated genes (Figure 6A). Furthermore, analysis of ABA-induced gene expression of MpABI3, which is thought to be a key regulator of ABA-triggered gemma dormancy (Eklund et al., 2018), revealed that, although expression of the MpABI3 transcript was significantly reduced in the Mpark1/2ge and Mpark1/3ge double mutants, there was only a slight reduction observed in Mpark1ge (Supplementary Figure S9). These results indicate that the alleviation of gemma dormancy in Mpark1ge was achieved independent of the function of MpABI3. Further analysis of ABA- and B3-Raf-regulated genes should lead to the identification of key factors for the regulation of dormancy in vegetative tissues.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/, DRA014012.

Author contributions

DT and YS: conceptualization. AJ, YY, MI, TG, NY, HK, and KI: investigation. AS: data analysis. AJ, YS, and DT: writing and editing. DT, KI, and YS: funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (S1311017) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 20K06680, 18H04774, JP15H05955, and 19H03247) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Takayuki Kohchi for providing the Marchantia ecotype TAK-1 and the pMpGE10 and pMpGE11 vectors. We also thank Yasuo Niwa for GFP (S65T; Niwa, 2003), Ralph Quatrano for proEm-GUS, Tuan-hua David Ho for proUbi-LUC constructs, and the NODAI Genome Research Center of Tokyo University of Agriculture for RNA sequencing.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.952820/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akter K., Kato M., Sato Y., Kaneko Y., Takezawa D. (2014). Abscisic acid-induced rearrangement of intracellular structures associated with freezing and desiccation stress tolerance in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 1334–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.05.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F., Qanmber G., Li F., Wang Z. (2022). Updated role of ABA in seed maturation, dormancy, and germination. J. Adv. Res. 35, 199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.03.011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L., Jowett J., Hanhart C. J., Koornneef M. (2006). Cloning of DOG1, a quantitative trait locus controlling seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 17042–17047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607877103, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhyan S. B., Minami A., Kaneko Y., Suzuki S., Arakawa K., Sakata Y., et al. (2012). Cold acclimation in the moss Physcomitrella patens involves abscisic acid-dependent signaling. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.08.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. L., Kohchi T., Yamato K. T., Jenkins J., Shu S., Ishizaki K., et al. (2017). Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell 171, 287–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.030, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A. H., Quail P. H. (1996). Ubiquitin promoter-based vectors for high-level expression of selectable and/or screenable marker genes in monocotyledonous plants. Transgenic Res. 5, 213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01969712, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuming A. C. (2009). “Moss as a model system for plant stress responses,” in Plant Stress Biology. ed. Hirt H. (Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.), 17–36. doi: 10.1002/9783527628964.ch2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Finkelstein R. R., Abrams S. R. (2010). Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 651–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund D. M., Kanei M., Flores-Sandoval E., Kishizaki K., Nishihama R., Kohchi T., et al. (2018). An evolutionarily conserved abscisic acid signaling pathway regulates dormancy in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Curr. Biol. 28, 3691–3699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.10.018, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R. R., Gampala S. S., Rock C. D. (2002). Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell 14, S15–S45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010441, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H., Chinnusamy V., Rodrigues A., Rubio S., Antoni R., Park S. Y., et al. (2009). In vitro reconstitution of an abscisic acid signalling pathway. Nature 462, 660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature08599, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Nakashima K., Yoshida T., Katagiri T., Kidokoro S., Kanamori N., et al. (2009). Three SnRK2 protein kinases are the main positive regulators of abscisic acid signaling in response to water stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 2123–2132. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp147, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J., Hauge B. M., Valon C., Smalle J., Parcy F., Goodman H. M. (1992). Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell 4, 1251–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka R., Furuki T., Shimizu T., Takezawa D., Kikawada T., Sakurai M., et al. (2014). Biochemical and structural characterization of an endoplasmic reticulum-localized late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein from the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 454, 588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.130, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath D. P., Anderson J. V., Chao W. S., Foley M. E. (2003). Knowing when to grow: signals regulating bud dormancy. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.013, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki K., Chiyoda S., Yamato K. T., Kohchi T. (2008). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the haploid liverwort Marchantia polymorpha L., an emerging model for plant biology. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn085, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki K., Nishihama R., Ueda M., Inoue K., Ishida S., Nishimura Y., et al. (2015). Development of gateway binary vector series with four different selection markers for the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. PLoS One 10:e0138876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138876, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M., Inoue T., Hiraide M., Khatun N., Jahan A., Kuwata K., et al. (2021). Activation of SnRK2 by Raf-like kinase represents a primary mechanism of ABA and abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 185, 533–546. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiaa046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan A., Komatsu K., Wakida-Sekiya M., Hiraide M., Tanaka K., Ohtake R., et al. (2019). Archetypal roles of an abscisic acid receptor in drought and sugar responses in liverworts. Plant Physiol. 179, 317–328. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00761, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Yasui Y., Ishizaki K. (2020). Gemma cup and gemma development in Marchantia polymorpha. New Phytol. 228, 459–465. doi: 10.1111/nph.16655, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuta S., Masuda G., Bak H., Shinozawa A., Kamiyama Y., Umezawa T., et al. (2020). Arabidopsis Raf-like kinases act as positive regulators of subclass III SnRK2 in osmostress signaling. Plant J. 103, 634–644. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14756, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode A. R. (2005). Role of abscisic acid in seed dormancy. J. Plant Growth Regul. 24, 319–344. doi: 10.1007/s00344-005-0110-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu K., Nishikawa Y., Ohtsuka T., Taji T., Quatrano R. S., Tanaka S., et al. (2009). Functional analyses of the ABI1-related protein phosphatase type 2C reveal evolutionarily conserved regulation of abscisic acid signaling between Arabidopsis and the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Mol. Biol. 70, 327–340. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9476-z, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu K., Suzuki N., Kuwamura M., Nishikawa Y., Nakatani M., Ohtawa H., et al. (2013). Group a PP2Cs evolved in land plants as key regulators of intrinsic desiccation tolerance. Nat. Commun. 4:2219. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3219, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu K., Takezawa D., Sakata Y. (2020). Decoding ABA and osmostress signalling in plants from an evolutionary point of view. Plant Cell Environ. 43, 2894–2911. doi: 10.1111/pce.13869, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota A., Ishizaki K., Hosaka M., Kohchi T. (2013). Efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha using regenerating thalli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77, 167–172. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120700, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang G. A. (1987). Dormancy: a new universal terminology. Hort. Sci. 22, 817–820. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Lee M. H., Kim J. I., Kim S. Y. (2014). Arabidopsis putative MAP kinase kinase kinases Raf10 and Raf11 are positive regulators of seed dormancy and ABA response. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 84–97. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Li Y., Zhang Z., Liu X., Hsu C.-C., Du Y., et al. (2020). A RAF-SnRK2 kinase cascade mediates early osmotic stress signaling in higher plants. Nat. Commun. 11:613. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14477-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Szostkiewicz I., Korte A., Moes D., Yang Y., Christmann A., et al. (2009). Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324, 1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1172408, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte W. R., Jr., Russel S. H., Quatrano R. S. (1989). Abscisic acid-responsive sequences from the Em gene of wheat. Plant Cell 1, 969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q. T. C., Lee S. J., Choi S. W., Na Y. J., Song M. R., Hoang Q. T. N., et al. (2019). Arabidopsis Raf-like kinase Raf10 is a regulatory component of core ABA signaling. Mol. Cells 42, 646–660. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.0173, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N., Yoshida T., Murayama M., Asami T., Shinozaki K., Hirayama T. (2004). Isolation and characterization of novel mutants affecting the abscisic acid sensitivity of Arabidopsis germination and seedling growth. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1485–1499. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch171, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y. (2003). A synthetic green fluorescent protein gene for plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnology 20, 1–11. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.20.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W., Liang J., Sui J., Li J., Liu C., Xin Y., et al. (2021). ABA and bud dormancy in perennials: current knowledge and future perspective. MDPI Genes 12:1635. doi: 10.3390/genes12101635, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Fung P., Nishimura N., Jensen D. R., Fujii H., Zhao Y., et al. (2009). Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324, 1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1173041, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence V. C., Dunford S. S., Redella S. (2005). Differential effects of abscisic acid on desiccation tolerance and carbohydrates in three species of liverworts. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.02.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing S., Lang D., Zimmer A. D., Terry A., Salamov A., Shapiro H., et al. (2008). The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 319, 64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1150646, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah S. K., Reddy K. R., Li J. (2016). Abscisic acid and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:571. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saruhashi M., Kumar Ghosh T., Arai K., Ishizaki Y., Hagiwara K., Komatsu K., et al. (2015). Plant Raf-like kinase integrates abscisic acid and hyperosmotic stress signaling upstream of SNF1-related protein kinase2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, E6388–E6396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511238112, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M. D., Hoekstra F. A., Hsing Y. I. C. (2008). Late embryogenesis abundant proteins. Adv. Bot. Res. 48, 211–255. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)00404-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozawa A., Otake R., Takezawa D., Umezawa T., Komatsu K., Tanaka K., et al. (2019). SnRK2 protein kinases represent an ancient system in plants for adaptation to a terrestrial environment. Commun. Biol. 2:30. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0281-1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson S.-R., Kamisugi Y., Trinh C. H., Schmutz J., Jenkins J. W., Grimwood J., et al. (2016). Genetic analysis of Physcomitrella patens identifies ABSCISIC ACID NON-RESPONSIVE (ANR), a regulator of ABA responses unique to basal land plants and required for desiccation tolerance. Plant Cell 28, 1310–1327. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00091, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano S. S., Nishihama R., Shirakawa M., Takagi J., Matsuda Y., Ishida S., et al. (2018). Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing and its application to conditional genetic analysis in Marchantia polymorpha. PLoS One 13, 1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Harpazi B., Wijerathna-Yapa A., Merilo E., de Vries J., Michaeli D., et al. (2019). A ligand-independent origin of abscisic acid perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 24892–24899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914480116, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Zhang J., Hsu P. K., Ceciliato P. H. O., Zhang L., Dubeaux G., et al. (2020). MAP3Kinase-dependent SnRK2-kinase activation is required for abscisic acid signal transduction and rapid osmotic stress response. Nat. Commun. 11:12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13875-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa D., Komatsu K., Sakata Y. (2011). ABA in bryophytes: how a universal growth regulator in life became a plant hormone? J. Plant Res. 124, 437–453. doi: 10.1007/s10265-011-0410-5, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toriyama T., Shinozawa A., Yasumura Y., Saruhashi M., Hiraide M., Ito S., et al. (2022). Sensor histidine kinases mediate ABA and osmostress signaling in the moss Physcomitrium patens. Curr. Biol. 32, 164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.068, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougane K., Komatsu K., Bhyan S. B., Sakata Y., Ishizaki K., Yamato K. T., et al. (2010). Evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanisms of abscisic acid signaling in land plants: Characterization of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE1-like type 2C protein phosphatase in the liverwort M. polymorpha. Plant Physiol. 152, 1529–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Sugiyama N., Mizoguchi M., Hayashi S., Myouga F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2009). Type 2C protein phosphatases directly regulate abscisic acid-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 17588–17593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/, DRA014012.