Abstract

Pseudomonas abietaniphila BKME-9 is able to degrade dehydroabietic acid (DhA) via ring hydroxylation by a novel dioxygenase. The ditA1, ditA2, and ditA3 genes, which encode the α and β subunits of the oxygenase and the ferredoxin of the diterpenoid dioxygenase, respectively, were isolated and sequenced. The ferredoxin gene is 9.2 kb upstream of the oxygenase genes and 872 bp upstream of a putative meta ring cleavage dioxygenase gene, ditC. A Tn5 insertion in the α subunit gene, ditA1, resulted in the accumulation by the mutant strain BKME-941 of the pathway intermediate, 7-oxoDhA. Disruption of the ferredoxin gene, ditA3, in wild-type BKME-9 by mutant-allele exchange resulted in a strain (BKME-91) with a phenotype identical to that of the mutant strain BKME-941. Sequence analysis of the putative ferredoxin indicated that it is likely to be a [4Fe-4S]- or [3Fe-4S]-type ferredoxin and not a [2Fe-2S]-type ferredoxin, as found in all previously described ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. Expression in Escherichia coli of ditA1A2A3, encoding the diterpenoid dioxygenase without its putative reductase component, resulted in a functional enzyme. The diterpenoid dioxygenase attacks 7-oxoDhA, and not DhA, at C-11 and C-12, producing 7-oxo-11,12-dihydroxy-8,13-abietadien acid, which was identified by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance, UV-visible light, and high-resolution mass spectrometry. The organization of the genes encoding the various components of the diterpenoid dioxygenase, the phylogenetic distinctiveness of both the α subunit and the ferredoxin component, and the unusual Fe-S cluster of the ferredoxin all suggest that this enzyme belongs to a new class of aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases.

Resin acids are diterpenoid carboxylic acids which occur naturally in trees. Resin acids are more abundant in softwoods, such as pines, in which they can account for up to a few percent of biomass (38). Considering the total biomass of softwoods, resin acids are an abundant form of organic carbon in the biosphere, which must be processed in the global carbon cycle.

There is a high degree of public concern over the discharge of pulp and paper effluents into the environment. In Canada, regulations controlling the discharge of these effluents include limits on biological oxygen demand, total suspended solids, and acute toxicity. Leach and Thakore (25) reported that three resin acid soaps were responsible for over 80% of kraft effluent toxicity to juvenile coho salmon. The percentage of dehydroabietic acid (DhA) in the total resin acid content of an effluent varies significantly among pulp and paper mills. It is mainly dependent on the type of wood, the pulping process (kraft, thermomechanical, or chemithermomechanical), and the effluent treatment system the mill is using. Values between 10 and 50% have been reported in the literature (38). In addition to their contribution to pulp and paper mill effluent toxicity, resin acids are a component of pitch, which interferes with the paper-making process. In recent years, an effort to reduce or eliminate wastewater discharges has resulted in increases in resin acid concentrations in the process streams of pulp and paper mills, magnifying the existing problems. Although the contribution of these compounds to effluent toxicity and pitch formation has been well documented, knowledge of the biochemical pathway(s) of resin acid degradation by organisms found in both natural habitats and biological wastewater treatment systems is lacking.

Recently, several studies have reported the isolation of aerobic bacteria that use resin acids as growth substrates (7, 28, 30, 39). Pseudomonas abietaniphila BKME-9, a strain isolated from an aerated lagoon treating bleached kraft wood pulp mill effluent, was found to use abietane- but not pimerane-type diterpenoids via an inducible metabolic activity (7). Although this metabolic activity was investigated, the catabolic pathway used by this organism for DhA degradation was not determined. Biellmann et al. (8) reported on the degradation of DhA by Flavobacterium resinovorum and proposed that catabolism proceeds via hydroxylation at C-3 to form the alcohol, followed by oxidation to the ketone, which would undergo spontaneous or enzymatic decarboxylation at the C-4 position. In follow-up work (9), they also found evidence of oxidation at C-7 to form 7-oxoDhA prior to dihydroxylation of the aromatic ring at C-11 and C-12 to form a diol. Partial elucidation of the DhA metabolic pathways of a Pseudomonas sp. and an Alcaligenes sp. also demonstrated oxidative attack at the C-7 position prior to dihydroxylation but found that these two strains did not oxidize C-3 or decarboxylate C-4 (9). Although no genes or enzymes of the pathway were isolated, the formation of a diol intermediate suggests the involvement of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase enzyme.

In this study we describe the cloning and characterization of a novel ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, DitA, found in P. abietaniphila BKME-9. Unlike the genes encoding most ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases characterized to date, the genes encoding the three components of DitA, the putative ferredoxin reductase, the ferredoxin, and the oxygenase, are found in separate transcriptional units. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of the ferredoxin component of DitA indicates that it has little similarity to plant-type or Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins known to be associated with all previously characterized dioxygenases. This novel ferredoxin appears to be a [4Fe-4S]- or [3Fe-4S]-type ferredoxin. Although only the oxygenase and the ferredoxin components of DitA were cloned, it was possible to reconstitute the dioxygenase activity in Escherichia coli. The above-mentioned characteristics of DitA suggest that it belongs to a new class of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, 10 μg of gentamicin per ml, 30 μg of kanamycin per ml, or 12 μg of tetracycline per ml. P. abietaniphila BKME-9 was grown at 30°C on tryptic soy broth (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) or mineral medium supplemented with 1 g of Na pyruvate/liter or 0.1 g of one the diterpenoids (DhA, abietic acid [AbA], or 7-oxoDhA)/liter, as previously described (28). Resin acids were supplied by Helix Biotechnologies, Richmond, Canada.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. abietaniphila | ||

| BKME-9 | Wild-type; DhA+ | 7 |

| BKME-941 | ditA1::Tn5 mutant; DhA− | This study |

| BKME-91 | ditA3::xylE-Gmr mutant; DhA− | This study |

| BKME-91(pVM120) | Rescued BKME-91 mutant with pVM120; DhA+ | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF) U169 deoR (φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15) | Gibco BRL |

| XL1 Blue MR | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| S17-1 | recA pro thi hsdR with integrated RP4-2Tc::Mu-kan::Tn7 Tra+ Tpr Smr | 35 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Apr | 40 |

| pSL1190 | Apr | Pharmacia |

| pSUP2021 | Conjugable Tn5 mutagenesis vector; Apr Kmr | 35 |

| SuperCos1 | Cosmid vector; Apr | Stratagene |

| pEX100T | sacB conjugable plasmid for gene replacement; Apr | 34 |

| pX1918G | xylE-Gmr fusion cassette-containing plasmid; Apr | 34 |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Conjugable broad-host-range vector; Kmr | 23 |

| pAJ130 | fdx1 and redA2 encoding type IIA electron transfer proteins cloned into pVLT35 | 3 |

| pUCP27 | Conjugable broad-host-range vector; Tcr | 33 |

| pIPCRM41 | pCRII containing IPCRM41 product from BKME-941 mutant | 27 |

| pLC12 | SuperCos1 cosmid library clone containing DhA degradation genes | This study |

| pVM1 | 5.8-kb EcoRI fragment of pLC12 into EcoRI of pSL1190 | This study |

| pVM1R | Reverse orientation of 5.8-kb EcoRI fragment of pSL1190 | This study |

| pVM2 | 9.8-kb EcoRI fragment from pLC12 into EcoRI of pUC19 | This study |

| pVM4 | 3.6-kb EcoRI-SmaI fragment from pVM2 into EcoRI-SmaI of pUC19 | This study |

| pVM5 | 4.3-kb SmaI fragment from pVM2 into SmaI of pUC19 | This study |

| pVM10 | 891-bp NaeI fragment from pVM4 into SmaI of pEX100T | This study |

| pVM101 | HindIII xylE-Gmr cassette from pX1918G into unique HindIII of pVM10 | This study |

| pVM20 | KpnI-BamHI PCR product containing ditA1 and ditA2 in pBBR1MCS-2 | This study |

| pVM120 | 891-bp NaeI fragment from pVM4 into SmaI of pUCP27 | This study |

DhA+, grows on DhA; DhA−, does not grow on DhA.

Tn5 mutagenesis and inverse PCR.

Conjugation for Tn5 transposon mutagenesis with pSUP2021 (35) was carried out on 0.45-μm-pore-size sterile membranes (diameter, 13 mm) placed on tryptic soy agar at 30°C with a 3:1 donor-to-recipient ratio. Tn5 transconjugants were selected on mineral medium supplemented with Na pyruvate and kanamycin (30 μg/ml). Mutants were identified by replica plating on mineral medium supplemented with DhA and kanamycin. Mutants that failed to grow on DhA were screened by gas chromatography-flame ionization detection (GC-FID) for the production of pathway intermediates, using a cell suspension assay as described below. DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion in BKME-941 was isolated by a modified inverse-PCR (IPCR) method as described by Martin and Mohn (27).

Genomic library construction and screening.

Genomic DNA from strain BKME-9 was isolated and purified as previously described (11). The DNA was partially digested with MboI and ligated to BamHI-digested SuperCos1 (Stratagene, LaJolla, Calif.) cosmid arms, as described by the supplier. The ligated DNA was packaged in vitro with the Gigapack III Gold packaging extract (Stratagene). E. coli XL1 Blue MR was transfected with the packaged DNA, and library clones were selected on LB medium containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml. The cosmid genomic library was screened by colony lift with Nytran nylon membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). The immobilized DNA was hybridized to the IPCR product labeled with [α32-P]dCTP (NEN, Boston, Mass.) by using the nick translation system from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.). Cosmid DNA from minilysate of positive clones was analyzed by Southern hybridization, using a standard technique (4), to confirm the presence of the IPCR sequence in the cosmid insert and map it.

DNA manipulation, sequencing, and analysis.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by the standard alkali lysis method (4). Restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass., or Gibco BRL) digestions were performed by standard procedures. Ligation mixtures were incubated at 15°C overnight or at room temperature for 2 to 3 h with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) and used to transform E. coli cells made competent by the RbCl method, as described by Hanahan (18), or by electroporation according to the protocol supplied with the Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) gene pulser. Strain BKME-9 was transformed by electroporation as previously described (14). Plasmids pUC19 or pSL1190 and E. coli DH5α were used for the subcloning of pLC12 fragments needed for DNA sequencing. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels with QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.), and templates for DNA sequencing were purified with QIAprep spin columns (Qiagen). Successive unidirectional deletions of DNA were prepared for sequencing large fragments by using the double-stranded nested-deletion system from Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). Oligonucleotide primers synthesized at the Nucleic Acid and Protein Services unit at the University of British Columbia were used to sequence DNA regions not covered by the deletions. DNA sequences were determined by the Nucleic Acid and Protein Services unit by using AmpliTaq dye terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems) and Centri-Sep columns (Princeton Separation, Adelphia, N.J.) to purify the extension products. Clone Manager for Windows (version 4.01) and Primer Designer (version 2.0) were used for sequence analysis and PCR primer design. ClustalX and PHYLIP were used to align sequences and generate the phylogenetic tree.

Knockout of the ferredoxin (ditA3) by gene replacement.

A gene replacement plasmid was constructed by subcloning an 891-bp NaeI fragment of cosmid pLC12 into the unique SmaI site of pEX100T containing the sacB counterselectable marker to produce pVM10 and by inserting the xylE-Gmr transcriptional fusion antibiotic cassette from pX1918G into the unique HindIII site of ditA3. The plasmid was conjugally transferred to BKME-9 by using the E. coli mobilizing strain S17-1. Colonies containing integrated plasmids were selected on mineral medium supplemented with Na pyruvate and 4 μg of gentamicin per ml. Isolated colonies, which appeared after 48 h at 30°C, were plated on the same medium supplemented with 5% sucrose. Successful gene replacement was monitored by colony PCR (42) with primers targeted to the ferredoxin gene (VMFd1, 5′-ACTCAGGCAGCGTTGTC-3′, and VMFd2, 5′-ATGGAGCTGCATTGCAC-3′) at an annealing temperature of 58°C.

Biotransformation of DhA by P. abietaniphila BKME-9 resting cells.

Suspensions of BKME-9 cells were grown overnight at 30°C in 250 ml of mineral medium supplemented with 0.1% Na pyruvate, washed once in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and suspended in 50 ml of the same medium at a final optical density at 610 nm (OD610) of ∼3.0. DhA (333 mM) was dissolved in methanol and added to the cell suspension at a final concentration of 333 μM. The cell suspensions were incubated on a rotary shaker at 30°C. Samples (1.5 ml) were taken at regular intervals and immediately frozen at −20°C. Thawed samples were analyzed by GC-FID for the production of pathway intermediates, using the method previously described for DhA analysis (28), and UV-visible light (UV-Vis) absorption spectra of culture supernatants (1 ml) were measured with a Cary 1E spectrophotometer (Varian).

Expression of diterpenoid dioxygenase in E. coli.

The pUC-based plasmid pVM10, which was constructed for the ditA3 knockout, was also used for expression of the ferredoxin. The oxygenase (α and β subunit) genes were cloned into the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-2 by PCR. A 2,108-bp fragment containing ditA1, its putative ribosomal binding site, and ditA2 was amplified with primers VM100 (5′-CGGGGTACCGGCTCGGAGTA-3′) and VM101 (5′-CGCGGATCCTTAGAGGAATACCGC-3′), which introduced KpnI and BamHI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The PCR product was cloned into pBBR1MCS-2, which was previously digested with the same endonucleases, to produce pVM20. For expression of the enzyme, plasmids were introduced into E. coli XL1 Blue MR, and 100 ml of prewarmed LB broth containing the appropriate antibiotic(s) was inoculated (1%) with an overnight culture and grown to logarithmic phase (OD610, ∼0.6). The cultures were cooled on ice, harvested, washed once in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and suspended in 20 ml of 0.1% glycerol mineral medium at a final OD610 of ∼3.0. DhA (333mM) and 7-oxoDhA (318mM) were dissolved in methanol and added to cell suspensions at final concentrations of 333 and 318 μM, respectively. Triplicate 0.5-ml samples were taken at 1-h intervals, acidified with 1 drop of 1.2 N HCl, and immediately frozen at −20°C. The removal of the substrate and the production of the dihydrodiol were monitored by GC-FID, as for resting cell suspensions.

Purification and identification of the dihydrodiol.

A 500-ml suspension of E. coli cells expressing the dioxygenase was incubated overnight (37°C; 180 rpm) in mineral medium with 50 mg of 7-oxoDhA. The acidified (pH 3.0) culture supernatant was extracted twice with ethyl acetate, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuum in a rotoevaporator. The dihydrodiol of 7-oxoDhA, which precipitated out of solution during ethyl acetate concentration, was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (0.5-mm thickness silica gel, 60Å, with fluorescent indicator; Whatman, Clifton, N.J.) with benzene-methanol-acetic acid (79:20:1 [vol/vol/vol]) as a developing solvent. UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 1E spectrophotometer. GC electron impact (EI) mass spectrometry (MS) was performed with a Varian 3400 gas chromatograph equipped with a Varian Saturn 4D ion trap mass spectrometer and a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm [inside diameter]; 0.25-μm film thickness; J&W Scientific). The GC oven temperature program was 70°C for 2 min and then 10°C/min to 280°C, with an injector and detector temperature of 260 and 290°C, respectively. Prior to 1-μl injection, samples were derivatized by sparging with ethereal vapor of diazomethane to form methyl esters. High-resolution (EI) mass spectra were recorded with a Kratos MS50 at 70 eV and 150°C. Proton (1H) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded with a Bruker-WH400.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences reported in this study have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession no. AF119621.

RESULTS

Tn5 mutagenesis and isolation of cosmid clone.

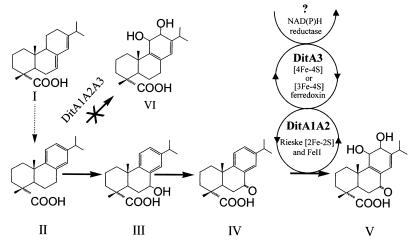

Transposon mutagenesis was used to obtain Tn5 insertion mutants of P. abietaniphila BKME-9 which were no longer capable of growing on DhA as a sole carbon source. These mutants were subsequently screened for the accumulation of biodegradation pathway intermediates by a cell suspension assay. One of the DhA− isolates, strain BKME-941, was found to accumulate a 7-oxoDhA intermediate (Fig. 1, compound IV). The identity of this metabolite was confirmed by comparison of its GC retention time and mass spectrum to those of a pure analytical standard. A modified inverse-PCR method was used to isolate the DNA sequences flanking the Tn5 insertion in BKME-941 and to rapidly obtain a partial sequence of the disrupted gene. A 1.4-kb fragment (IPCRM41) of BKME-941 was amplified by IPCR and cloned as previously described (27). The sequence analysis of IPCRM41 revealed that the transposon had been inserted into a gene with similarity to genes encoding the α subunit of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. Interestingly, this mutant also lost the ability to grow on AbA, a nonaromatic diterpenoid (Table 2). Screening of the BKME-9 wild-type Super-Cos1 cosmid library with the 1.4-kb inverse-PCR probe produced nine distinct positive clones. No dioxygenase activity was detected when these positive clones were tested for the production of indigo from indole and 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid from 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl. Moreover, these library clones did not metabolize DhA or 7-oxoDhA in resting cell suspension assays, but two library clones (pLC12 and pLC162) were able to metabolize 7-oxoDhA (but not DhA) in cultures growing on LB broth.

FIG. 1.

Proposed pathway for abietanic diterpenoid degradation in P. abietaniphila BKME-9. Compound designations: I, AbA; II, DhA; III, 7-hydroxy-DhA; IV, 7-oxoDhA; V, 7-oxo-11,12-dihydroxy-8,13-abietadien acid; VI, 11,12-dihydroxy-8,13-abietadien acid.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characterization of wild-type and mutant strains of P. abietaniphila BKME-9a

| Strain | Genotype | Growth on substrateb

|

DhA metab-olitec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate | DhA | 7-oxoDhA | AbA | |||

| BKME-9 | Wild-type | + | + | + | + | None |

| BKME-941 | ditA1::Tn5 | + | − | − | − | IV |

| BKME-91 | ditA3::xylE-Gmr | + | − | − | − | IV |

| BKME-910 | ditA3::xylE-Gmr (pVM120) | + | +d | +d | +d | None |

Growth of the cultures was monitored microscopically for a period of 3 days.

+, growth; −, no growth.

See Fig. 1.

Growth restored but slower (48 h) than wild type (24 h) to reach stationary phase.

Identification of the oxygenase genes ditA1 and ditA2.

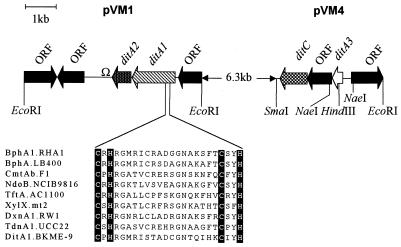

A 5.8-kb EcoRI band, which hybridized to the inverse-PCR probe (IPCRM41) in eight of the library clones, was further subcloned from the cosmid pLC12 into pSL1190 in both orientations, yielding pVM1 and pVM1R. Plasmid constructs were subjected to unidirectional deletions for sequencing both strands, and the complete physical map of this EcoRI fragment is presented in Fig. 2. Three complete and two partial open reading frames (ORFs) were identified. Two ORFs, designated ditA1 and ditA2, were similar to the genes encoding the α and β subunits of the oxygenase components of several bacterial ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. The DNA sequence of the inverse-PCR probe was in perfect agreement with the sequence of ditA1, confirming that we had isolated the gene corresponding to the one disrupted in BKME-941. The deduced amino acid sequences of DitA1A2 consisted of polypeptides of 469 and 201 amino acids, with calculated molecular masses of 52.5 and 22.9 kDa, respectively. From the primary amino acid sequence alignment of DitA1 and NDO, a naphthalene dioxygenase for which the three-dimensional structure was recently solved (21), we identified the highly conserved consensus sequences for the coordination of a [2Fe-2S] Rieske-type cluster (Fig. 2) and a catalytic nonheme iron. The [2Fe-2S] cluster-binding sequence (Cys-X-His-X17-Cys-X2-His) was located at residues 91 to 114, and the catalytic iron coordination residues were His219, His224, and Asp399 (corresponding to His 208, His213, and Asp362 of NDO). Although several features common to the α subunit of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases are present in DitA1, it has only weak overall sequence similarity to other proteins of this family. The α subunits of biphenyl dioxygenases from several Rhodococcus sp. strains showed the highest sequence similarity to DitA1, exhibiting up to 30% identity. Both ditA1 and ditA2 are translated from the ATG start codon and are preceded by a potential ribosomal binding site. A 25-bp stem-loop located 43 bp downstream of the ditA2 gene (Fig. 2) probably serves as a rho-independent transcription termination site, indicating the likely end of an operon. The segments of cloned DNA flanking ditA1A2 did not contain genes similar to those encoding electron transport proteins typically associated with ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases.

FIG. 2.

Physical map of the two loci from the library clone pLC12 carrying DhA degradation genes of P. abietaniphila BKME-9 and alignment of protein sequences of [2Fe-2S] binding domains of α subunits of several classes of dioxygenases. ditA1 encodes the α subunit of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, ditA2 encodes the β subunit of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, ditA3 encodes ferredoxin, and ditC encodes ring cleavage dioxygenase. Sequence abbreviations are defined in the legend to Fig. 7.

Identification of the ferredoxin gene ditA3.

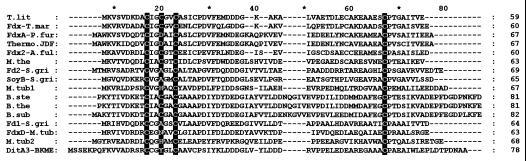

Since the genes encoding electron transport proteins are usually contiguous to those encoding their oxygenase counterparts, we decided to obtain additional sequence information upstream of ditA1A2. For that purpose, a 9.8-kb EcoRI fragment from pLC12, located upstream of the 5.8-kb EcoRI fragment containing ditA1A2, was cloned into pUC19, resulting in pVM2. A 3.6-kb SmaI-EcoRI fragment of pVM2 was further subcloned in pUC19 (pVM4) to produce a DNA insert of adequate size for nested deletions and sequencing of both strands. Examination of the sequence indicated that it contained three complete and one partial ORF (Fig. 2). Alignment searches with the BLAST program (2) identified one ORF encoding a protein with similarity to both [4Fe-4S]- and [3Fe-4S]-type ferredoxins. This ORF, designated ditA3, was located 9.2 kb upstream of ditA1 and is transcribed from the same strand. Preliminary DNA sequence analysis of the 9.2-kb region between ditA1 and ditA3 indicates that the two genes are probably regulated by different promoters. Although five potential methionine start codons are possible for this ferredoxin gene, we suspect that the correct start codon is the one encoding a 78-amino-acid protein (the smallest of the five possible ferredoxins), since protein alignments to similar ferredoxins did not extend to the N terminus of the longer possible DitA3 ferredoxins (Fig. 3). Examination of the nucleotide sequence preceding this ORF identified a possible ribosomal binding site (GGAGA) and a putative ntr-like promoter consensus sequence, TGGAGCN5TTGCA (12), 89 bp upstream of the Met start codon. The percent amino acid identities of the putative DitA3 ferredoxin to [4Fe-4S] or [3Fe-4S] ferredoxins are low, ranging from 22 to 36% for the ferredoxins listed in Fig. 3. Analysis of the amino acid composition of DitA3 reveals that it contains five cysteine residues. This protein is unusual in that its putative consensus sequence for [Fe-S] cluster coordination consists of three Cys and one Tyr residues (Cys-X2-Tyr-X2-Cys-Xn-Cys) rather than the typical four Cys residues (Fig. 3). Deviations from the consensus sequence have been observed in some proteins, where Asp can act as a fourth ligand (1) or, in the case of Ala substitution, where the protein adopts a [3Fe-4S] form (31). It is impossible to predict if the Tyr residue in DitA3 can act as a cluster-coordinating ligand; thus, the cluster geometry will have to be determined experimentally. An ORF (ditC) with sequence similarity to several meta ring cleavage dioxygenase genes was located 872 bp downstream of the ditA3 gene (Fig. 2). This led us to hypothesize that this ferredoxin was associated with the terminal oxygenase, DitA1A2, previously identified and that both the hydroxylating and the cleavage dioxygenases are involved in the oxidation of the aromatic ring of DhA.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the ferredoxin, DitA3, to the most similar 4Fe-4S and 3Fe-4S ferredoxins found in the SwissProt, GenBank, and EMBL databases. Conserved residues in iron-sulfur clusters are highlighted. The sequence abbreviations and accession numbers are as follows: T.lit, Thermococcus litoralis 4Fe-4S (P29604); Fdx-T.mar, Thermotoga maritima (x82178); FdxA-P.fur, Pyrococcus furiosus 4Fe-4S (P29603); Thermo.JDF, Thermococcus sp. strain JDF-3 4Fe-4S (U56939); Fdx2-A.ful, Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AE001095); M.the, Moorella thermoacetica 4Fe-4S (P00203); Fd2-S.gri, Streptomyces griseolus 3Fe-4S (P18325); SoyB-S.gri, Streptomyces griseus (P26910); M.tub1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (AL022021); B.ste, Bacillus stearothermophilus (P00212); B.the, Bacillus thermoproteolyticus 4Fe-4S (P10245); B.sub, Bacillus subtilis (P50727); Fd1-S.gri, S. griseolus 3Fe-4S (P18324); FdxD-M.tub, M. tuberculosis (AL022022); M.tub2, M. tuberculosis (Z80226); DitA3-BKME, P. abietaniphila BKME-9 (AF119621).

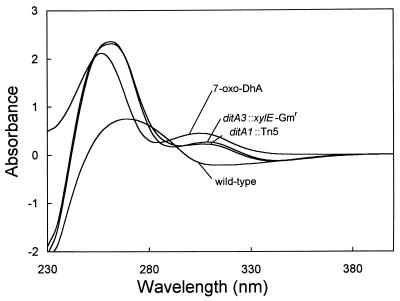

Phenotypic characterization of the ferredoxin (ditA3) mutant BKME-91.

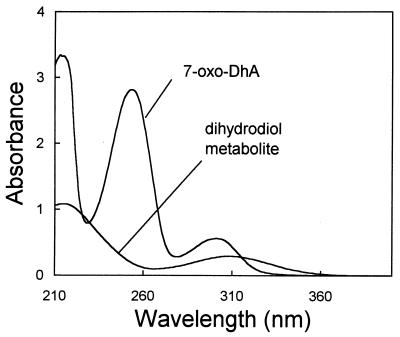

To determine the possible role of the putative ferredoxin in diterpenoid degradation, a chromosomal mutation in ditA3 was constructed by allelic exchange to insert a xylE-Gmr transcriptional fusion cassette containing no terminator sequence (34). DhA was added to cell suspensions of BKME-9 (wild type), BKME-941 (ditA1::Tn5), or BKME-91 (ditA3::xylE-Gmr), and the metabolites were analyzed by GC-MS and UV-Vis absorption. The strain carrying the ferredoxin mutation exhibited a phenotype identical to that of the strain with the α-subunit Tn5 mutation (Fig. 4 and Table 2). GC-MS analysis of the media from both mutant strains identified 7-oxoDhA as the most abundant metabolite. UV-Vis absorption spectra of culture supernatants from the two mutants were nearly identical, but comparison to pure 7-oxoDhA dissolved in mineral medium showed a shift to the left for the 253-nm peak. This difference was probably due to residual DhA in the medium of the mutant-strain cell suspensions. The spectra clearly indicate the appearance of a peak in the 300- to 310-nm region, indicating the formation of a ketone. To rescue the ferredoxin mutation and discount possible polar effects caused by the insertion of the xylE-Gmr cassette, a 891-bp NaeI fragment was cloned from pVM4 into the SmaI site of the broad-host-range vector pUCP27, resulting in pVM120, containing ditA3 under the control of the lac promoter. Although strain BKME-91 harboring pVM120 did not completely revert to the wild-type phenotype, it regained the ability to grow, albeit more slowly, on DhA (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Absorption spectra of 7-oxoDhA and supernatants from cell suspensions incubated with DhA for 10 h; wild-type, BKME-9; ditA1::Tn5, terminal oxygenase mutant strain BKME-941; ditA3::xylE-Gmr, ferredoxin mutant strain BKME-91.

Oxidation of 7-oxoDhA by recombinant diterpenoid dioxygenase expressed in E. coli.

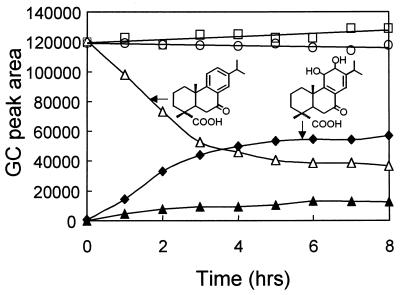

Diterpenoid dioxygenase activity was reconstituted in E. coli from a two-plasmid expression system similar to the one described by Armengaud et al. (3). Plasmids pVM20, containing the genes encoding the oxygenase (ditA1A2), and pVM10, containing the gene encoding the ferredoxin (ditA3), were introduced into E. coli XL1 Blue MR. When a suspension of this strain was incubated with 7-oxoDhA, the 7-oxoDhA was removed, and two metabolites were detected by GC-FID (Fig. 5). GC-MS analysis of the methyl ester derivatives showed that a third peak detected (not shown) was an artifact, resulting from the incomplete methylation of a hydroxyl group, as seen by a difference in mass of +14 for the molecular ion and the base peak. Interestingly, substrate transformation was only observed in cell suspensions supplemented with 0.1% glycerol (data not shown). Since the putative reductase component of the diterpenoid dioxygenase was not cloned, we assume that a reductase of the E. coli host substituted for the missing ferredoxin reductase in actively growing cultures. Parallel experiments demonstrated that the strain expressing the diterpenoid dioxygenase is unable to transform DhA (Fig. 1). A control strain expressing only ditA3, E. coli XL1 Blue MR(pBBR1MCS-2/pVM10), did not remove 7-oxoDhA in the same assay. Surprisingly, a control strain expressing only ditA1A2, E. coli XL1 Blue MR(pVM20/pEX100T), removed approximately 5% of the 7-oxoDhA (Fig. 5) and formed proportional amounts of the metabolites described above (not shown). Additionally, we used plasmid pAJ130 encoding a functional ferredoxin (Fdx1) and its reductase (RedA2) from the dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (3) to evaluate the functionality of a class IIA dioxygenase electron supply with the diterpenoid dioxygenase. Suspensions of E. coli(pVM20/pAJ130) cells expressing the genes encoding the class-IIA electron transfer proteins and DitA1A2 did not transform 7-oxoDhA.

FIG. 5.

Removal of 7-oxoDhA by suspensions of E. coli XL1 Blue MR cells expressing DitA3 (pVM10/pBBR1MCS-2) (□), DitA1A2 (pEX100T/pVM20) (○), or DitA1A2 plus DitA3 (pVM10/pVM20) (▵) and formation of the dihydrodiol (⧫) and a minor metabolite (▴) by the last.

Purification and identification of dioxygenase oxidation product.

We expected DitA to transform 7-oxoDhA to a nonaromatic dihydrodiol. Consistent with this expectation, the evidence provided by the UV-Vis, MS, and 1H NMR spectra indicate that the major metabolite produced by the diterpenoid dioxygenase is 7-oxo-11,12-dihydroxy-8,13-abietadien acid (Fig. 1, compound V). The substrate (7-oxoDhA) had the following characteristics: Rf value, 0.39 by TLC in benzene-methanol-acetic acid (79:20:1). UV-Vis (methanol) λmax, 213, 253, and 301 nm; GC-MS (methyl ester), molecular ion [M (% relative intensity)] at m/z 328 (21) and major fragment ions at m/z 296 (15), 269 (11), and 253 (100); 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.25 (J = 6.94, d, 6H), δ 1.29 (s, 1H), δ 1.34 (s, 1H), δ 7.39 (J = 8.22, d, 1H), δ 7.48 (J = 1.98, J = 2.11, dd, 1H), δ 7.81 (J = 2.09, d, 1H). The major metabolite had the following characteristics: Rf value, 0.35 by TLC in benzene-methanol-acetic acid (79:20:1). UV-Vis (methanol) λmax, 215 and 310 nm; GC-MS (methyl ester), molecular ion [M (% relative intensity)] at m/z 358 (62) and major fragment ions at m/z 343 (10), 326 (31), 283 (89), and 284 (100); high-resolution MS, apparent molecular ion at m/z 330.18231 (7) corresponding to a formula of C20H26O4 and a base peak at m/z 269.15532 (100) corresponding to C18H21O2; 1H NMR (CD3OD), δ 1.07 (J = 6.81, d, 3H), δ 1.12 (J = 6.80, d, 3H), δ 1.27 (s, 3H), δ 1.35 (s, 3H), δ 4.24 (J = 6.08, m, 1H), δ 4.38 (J = 4.99, d, 1H), δ 6.24 (J = 3.53, m, 1H).

UV-Vis spectra clearly show the loss of aromaticity of the purified metabolite (Fig. 6). Further evidence for the production of the diene came from the 1H NMR spectra, which show the loss of all three aromatic protons seen in 7-oxoDhA (δ 7.39, 7.48, and 7.81) and the appearance of one alkene proton on C-14 (δ 6.24) and two methine protons adjacent to the OH groups (δ 4.24 and 4.28). In addition, the CH3 signal for the isopropyl group of 7-oxoDhA occurs as a doublet at δ 1.25 but is split into two doublets at δ 1.07 and 1.12 for the metabolite, indicating the loss of aromaticity. The mass spectra of 7-oxoDhA and the major metabolite are in agreement with the EI mass fragmentation scheme of this family of compounds, as previously described (10, 13). GC and high-resolution mass spectra of the major product showed a compound with an M+ of −18 (H2O) relative to that of the expected dihydrodiol structure. High-resolution mass spectral analysis by chemical ionization with NH3 did not produce the expected molecular ion. Dehydration would be expected, given the unstable nature of this dihydrodiol.

FIG. 6.

Absorption spectra of 7-oxoDhA and the product of the dioxygenase, 7-oxo-11,12-dihydroxy-8,13-abietadien acid.

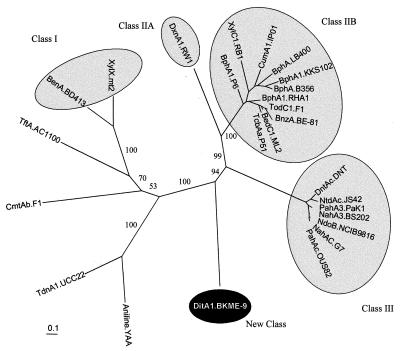

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe the cloning and expression of a new class of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. The diterpenoid dioxygenase, DitA, is like other ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases in its basic subunit structure, and those subunits have recognizable similarity to those of other dioxygenases. Like other dioxygenases, DitA catalyzes hydroxylation of an aromatic ring, forming a dihydrodiol. However, DitA is distinctive in several ways. First, the phylogenetic analysis of the protein sequence of the α subunit of DitA clearly indicates that DitA1 does not cluster with α subunits of the classes I, II, or III of dioxygenases but rather forms a distinct branch (Fig. 7). Furthermore, DitA does not belong to any of the oxygenase classes proposed by Batie et al. (5), which are distinguished by their variation in terminal oxygenase composition and their electron transport components. The ferredoxin components of all dioxygenase enzymes reported in the literature contain a [2Fe-2S]-type cluster, which functions as the electron supply to the oxygenase. However, the ferredoxin component of DitA appears to be of the [4Fe-4S] or [3Fe-4S] cluster type and has little sequence similarity to [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins. Finally, unlike most known dioxygenases, for which the genes encoding the components of the enzyme are found in the same transcriptional unit, DitA is encoded by genes at independent loci on the genome of BKME-9. This unusual organization of dioxygenase genes was also recently reported for a type IIA dioxin dioxygenase from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1, where the genes encoding the three components of the enzyme are separated by >40 kb (3).

FIG. 7.

Classification of α subunits from ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases based on the multiple alignment of related proteins. The phylogenetic tree (unrooted) was constructed by the PHYLIP protein distance and neighbor-joining methods, and confidence levels were determined by bootstrap analysis. The numbers on the branches represent percent confidence of 100 replicate analyses. The scale bar indicates percent divergence. The sequence abbreviations, enzyme substrate, species, and GenBank references are as follows: Aniline.YAA, aniline, Acinetobacter sp. strain YAA (D86080); TdnA1.UCC22, aniline, Pseudomonas putida UCC22 (D85415); XylX-mt2, toluate, P. putida mt2 (M64747); BenA.BD413, benzoate, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus BD143 (M76990); TftA.AC1100, 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid, Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 (U11420); CmtAb.F1, p-cymene, P. putida F1 (U24215); NdoB.NCIB9816, naphthalene, P. putida NCIB9816 (M23914); NahA3.BS202, naphthalene, P. putida BS202 (AF010471); PahAc.OUS82, polyaromatic hydrocarbon, P. putida OUS82 (D16629); NahAc.G7, naphthalene, P. putida G7 (M83949); PahA3.PaK1, naphthalene, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PaK1 (D84146); DntAc.DNT, 2,4-dinitrotoluene, Burkholderia sp. strain DNT (U62430); NtdAc.JS42, 2-nitrotoluene, Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42 (U49504); BedC1.ML2, benzene, P. putida ML2 (L04642); TodC1.F1, toluene, P. putida F1 (J04996); BnzA.BE-81, benzene, P. putida BE-81 (M17904); TcbAa.P51, chlorobenzene, Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 (U15298); BphA1.RHA1, biphenyl, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 (D32142); BphA1.P6, biphenyl, Rhodococcus globerulus P6 (X80041); BphA.LB400, biphenyl, B. cepacia LB400 (M86348); CumA1.IP01, isopropylbenzene, Pseudomonas fluorescens IP01 (D37828);BphA1.KKS102, biphenyl, Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 (D17319); BphA.B356, biphenyl, Comomonas testosteroni B356 (U47637); XylC1.RB1, substrate unknown, Cycloclasticus oligotrophus RB1 (U51165); DxnA1.RW1, dioxin, Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (AJ223219/223220); DitA1.BKME-9, dehydroabietic acid, P. abietaniphila BKME-9 (AF119621).

The protein sequence alignment of the α subunits of aromatic dioxygenases showed limited similarity between the catalytic domain (C terminal) of DitA1 and those of other dioxygenases. The residues lining the substrate pocket are not conserved between NDO and DitA1, with the exception of the three active-site iron ligands (His219, His224 and Asp399) and possibly Phe389 (21). This lack of similarity is expected, as the substrate specificity of dioxygenases is thought to be principally determined by the C termini of the α subunits of the terminal oxygenases (22, 32). Most of the similarity of DitA1 to other dioxygenases is limited to the Rieske domain, located between residues 48 and 170 (38 to 158 of NDO), and the region surrounding the putative ligands to the iron at the active site. The Asp216 residue, shown to be essential for toluene dioxygenase activity (20) and proposed to be a key residue in the electron transfer between the Rieske center and the iron at the active site (21), is also present in DitA1. In all likelihood, the path of electron transfer and oxygen activation at the active site of the diterpenoid dioxygenase is the same as for other classes of dioxygenases. However, given the atypical nature of the ferredoxin component of the diterpenoid dioxygenase, one would expect the binding site on DitA1 for DitA3 to be distinct from the binding sites on previously characterized terminal oxygenases for their respective [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins. In fact, the residues in the NDO α subunit (Lys97, Gly98, Val100, Gln115, Ser116, Pro118, and Trp211), thought to form a depression for interaction with the [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin, are not present in DitA1. These residues are also not fully conserved in α subunits of oxygenases from other classes, perhaps reflecting evolutionary adaptation of the oxygenases to interact with their respective ferredoxins.

The peculiar organization of the genes encoding the diterpenoid dioxygenase and the sequence of the ferredoxin proved to be problematic in the cloning of the genes encoding this enzyme. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to locate the ferredoxin component of DitA by PCR and Southern blotting, based on the expected conservation of the [2Fe-2S] cluster ligands and the ferredoxins observed in previously characterized dioxygenases. When enzyme assays with surrogate ferredoxins from type IIA and IIB dioxygenases coupled to DitA1A2 also failed (data not shown), we resorted to sequencing the DNA in the vicinity of ditA1A2, in the hope of finding the electron transport component(s) of the enzyme. The discovery of a putative [4Fe-4S] or [3Fe-4S] ferredoxin gene in the proximity of a ring cleavage dioxygenase gene (Fig. 2) suggested that this ferredoxin might be a component of the diterpenoid dioxygenase, despite not being phylogenetically related to [2Fe-2S]-type ferredoxins of known ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. The results from this study clearly established that the ferredoxin, DitA3, is a functional component of the diterpenoid dioxygenase. This is the first report of a [4Fe-4S]- or [3Fe-4S]-type ferredoxin functioning as an electron transport protein of a multicomponent dioxygenase, although such ferredoxins have been shown to supply electrons to multicomponent P-450 monooxygenases in Streptomyces spp. (31, 36). Interestingly, several proteins in the GenBank database with similarity to DitA3 are found in members of the Archaea and in gram-positive organisms (including thermophiles and anaerobes), but proteins with such similarity have not been found in members of the Proteobacteria (Fig. 3). The significance of this observation is unclear, but it suggests either an ancestral origin of DitA3 or acquisition of the gene from a distantly related organism.

The cloning in E. coli of the diterpenoid dioxygenase lacking the reductase (only DitA1A2A3) or lacking the reductase and the ferredoxin (only DitA1A2) both resulted in expression of the functional enzyme, although the activity was very low in the latter case (Fig. 5). This result was observed for other multicomponent dioxygenases (6, 24) and suggests relatively low specificity for electron transport components of some multicomponent oxygenase systems. This characteristic and the location of ditA3, ditA1A2, and the putative gene encoding the reductase, on separate transcriptional units suggest that the electron-transport proteins of the diterpenoid dioxygenase might be shared with other redox systems, possibly to maximize the catabolic potential while limiting its genetic burden. Harayama et al. (19) proposed that this tolerance between redox and oxygenase partners might also function as an evolutionary process for multicomponent oxygenases. Although some potential catabolic and evolutionary benefit may result from multipurpose electron transport proteins, it raises the question of coordination of expression of the genes. Are these electron transport proteins expressed constitutively or are they regulated? We are investigating the transcription coordination between ditA1A2 and ditA3 to address this question. The discovery of a new class of ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases for which the genes encoding the three components are unlinked shows that this characteristic is not restricted to the type IIA dioxygenases (3). The identification of homologues of DitA by examining other resin acid-degrading bacteria, or by large-scale sequencing projects, might reveal that this genetic organization is more common than previously thought.

The bacterial degradation of aromatic compounds is frequently initiated by their conversion to diol intermediates followed by cleavage of the aromatic ring. However, the initial attack of the aromatic diterpenoid DhA by P. abietaniphila BKME-9 occurs at two regions of the molecule, much like bile acid and steroid degradation by another Pseudomonas sp. (26). Previous studies reported that the hydroxylation at C-3 or C-7 precedes aromatic-ring oxidation in the DhA biodegradation pathway of a Pseudomonas sp., F. resinovorum, and an Alcaligenes sp. (8, 9). The product of C-7 oxidation, 7-oxoDhA, does occur in kraft pulp mill effluents (10), suggesting that this pathway of degradation is widespread. In the case of P. abietaniphila BKME-9, oxidation at C-7 is necessary before aromatic-ring hydroxylation, since DhA could not act as a substrate for the dioxygenase (Fig. 1). The initial oxidation at C-7 is consistent with the possible presence of a membrane-bound oxidase acting during uptake of the substrate, as in the alk system (37). The aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase, DitA, appears to be central to the biodegradation of abietanic diterpenoids, since a mutation in ditA1 or ditA3 inhibits growth of BKME-9 on the nonaromatic abietane AbA (Fig. 1 and Table 2). It is conceivable that nonaromatic diterpenoids may be aromatized to DhA by some yet-to-be-identified diterpenoid dehydrogenase(s) prior to ring hydroxylation. Previous work in our laboratory demonstrated that the ability of several members of the Proteobacteria (including BKME-9) to metabolize chlorinated DhA was correlated with their ability to metabolize DhA (29), suggesting that 12-ClDhA is degraded by the same enzyme system used to metabolize DhA. If this hypothesis holds true, it might indicate that the diterpenoid dioxygenase is capable of oxidative dechlorination. The potential dechlorination activity of the dioxygenase is of importance, since chlorinated DhA isomers, which are found in pulp and paper bleaching effluents, are more toxic and persistent than DhA (29, 41). Dioxygenase-catalyzed dechlorination was previously reported for the biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase of Burkholderia cepacia LB400 (formerly Pseudomonas cepacia), using chlorobiphenyl with substitution at the 2,2′ positions (17).

The search for a soluble, nontoxic inducer of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) degradation for use in PCB bioremediation has led to the hypothesis that plant terpenes may be the “natural” substrates for biphenyl biodegradation enzymes, or for their ancestors, since biphenyl is not naturally abundant (15). This raises the interesting question of whether the diterpenoid dioxygenase described in this study is ancestral to biphenyl dioxygenase. We have previously demonstrated that P. abietaniphila BKME-9 will not grow on biphenyl as a sole organic substrate (30). However, we have not tested the possible cometabolism of DhA and biphenyl by BKME-9 or the transformation of biphenyl by the cloned DitA enzyme. A structure-function analysis of potential inducers of PCB biodegradation by Arthrobacter sp. strain B1B suggested that isoprenoids were able to induce PCB degradation, with the most potent inducer being an aromatic isoprenoid (p-cymene) much resembling the aromatic region of the DhA molecule (Fig. 1) (16).

This study has reported a novel ring-hydroxylating diterpenoid dioxygenase found in P. abietaniphila BKME-9. We have previously shown that diverse bacteria degrade resin acids (30). Investigations of the occurrence of ditA1A2 and ditA3 homologues within these organisms might provide answers to questions about the distribution and evolution of this novel enzyme. Such information could be useful for ecological studies of pulp and paper effluent biological treatment systems, if conserved molecular probes targeting these genes can be used to study phylogenetically diverse guilds of resin acid degraders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Council of Forestry Industries of B.C., the Sustainable Forest Management Network Centres of Excellence, and the Industrial Research Chair in Forest Products Waste Management. Vincent J. J. Martin was supported by a B.C. Science Council postgraduate scholarship.

We thank Martin Tanner and Gordon Stewart for their help with the interpretation of the MS and 1H NMR spectral data. We are also grateful to Jean Armengaud for providing us with the plasmids pAJ130 and pBBR1MCS-2 and to Herbert Schweizer for pUCP27, pEX100T, and pX1918G. We also acknowledge Lindsay Eltis for his helpful discussions and Emma Master for critically reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M W W, Zhou Z H. Site-directed mutations of the 4Fe-ferredoxin from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: role of the cluster-coordinating aspartate in the physiological electron transfer reactions. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10892–10900. doi: 10.1021/bi9708141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armengaud J, Happe B, Timmis K N. Genetic analysis of dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1: catabolic genes dispersed on the genome. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3954–3966. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3954-3966.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batie C J, Ballou D P, Correll C C. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases. In: Müller F, editor. Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes. Vol. 3. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 546–566. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergeron J, Ahmad D, Barriault D, Larose A, Sylvestre M. Identification and mapping of the gene translation products involved in the first steps of the Comamonas testosteroni B-356 biphenyl/chlorobiphenyl biodegradation pathway. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:743–753. doi: 10.1139/m94-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bicho P A, Martin V, Saddler J N. Growth, induction, and substrate specificity of dehydroabietic acid-degrading bacteria isolated from a kraft mill effluent enrichment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;63:3014–3020. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3245-3250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biellmann J F, Branlant G, Gero-Robert M, Poiret M. Dégradation bactérienne de l’acide déhydroabiétique par un Flavobacterium resinovorum. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:1227–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biellmann J F, Branlant G, Gero-Robert M, Poiret M. Dégradation bactérienne de l’acide déhydroabiétique par un Pseudomonas et une Alcaligenes. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:1237–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownlee B, Strachan W M J. Distribution of some organic compounds in the receiving waters of a kraft pulp and paper mill effluent. J Fish Res Board Can. 1977;34:830–837. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns J L, Hedin L A, Lien D M. Chloramphenicol resistance in Pseudomonas cepacia because of decreased permeability. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:136–141. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon R. The xylABC promoter from the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid is activated by the nitrogen regulatory genes in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:129–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00330393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enzell C R, Wahlberg I. Mass spectrometric studies of diterpenes. Acta Chem Scand. 1969;23:871–891. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.23-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farinha M A, Kropinski A M. High efficiency electroporation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using frozen cell suspensions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Focht D D. Strategies for the improvement of aerobic metabolism of polychlorinated biphenyls. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert E S, Crowley D E. Plant compounds that induce polychlorinated biphenyl biodegradation by Arthrobacter sp. strain B1B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1933–1938. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1933-1938.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddock J D, Horton J R, Gibson D T. Dihydroxylation and dechlorination of chlorinated biphenyls by purified biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:20–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.20-26.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harayama S, Kok M, Neidle E L. Functional and evolutionary relationships among diverse oxygenases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:565–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Parales R E, Lynch N A, Gibson D T. Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved amino acids in the alpha subunit of toluene dioxygenase: potential mononuclear non-heme iron coordination sites. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3133–3139. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3133-3139.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kauppi B, Lee K, Carredano E, Parales R E, Gibson D T, Eklund H, Ramaswamy S. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure. 1998;6:571–586. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura N, Nishi A, Goto M, Furukawa K. Functional analyses of a variety of chimeric dioxygenases constructed from two biphenyl dioxygenases that are similar structurally but different functionally. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3936–3943. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3936-3943.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurkela S, Lehväslaiho H, Palva E T, Teeri T H. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and characterization of genes encoding naphthalene dioxygenase of Pseudomonas putida strain NCIB 9816. Gene. 1988;73:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach J M, Thakore A N. Identification of toxic constituents of kraft mill effluents that are toxic to juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) J Fish Res Board Can. 1973;30:479–484. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leppik R A. Steroid catechol degradation: disecoandrostane intermediates accumulated by Pseudomonas transposon mutant strains. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1979–1988. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-7-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, V. J. J., and W. W. Mohn. An alternative inverse PCR (IPCR) method to amplify DNA sequences flanking Tn5 transposon insertions. J. Microbiol. Methods, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Mohn W W. Bacteria obtained from a sequencing batch reactor that are capable of growth on dehydroabietic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2145–2150. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2145-2150.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohn W W, Stewart G R. Bacterial metabolism of chlorinated dehydroabietic acids occurring in pulp and paper mill effluents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3014–3020. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3014-3020.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohn, W. W., A. E. Wilson, P. Bicho, and E. R. B. Moore. Physiological and phylogenetic diversity of bacteria growing on resin acids. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.O’Keefe D P, Gibson K J, Emptage M H, Lenstra R, Romesser J A, Litle P J, Omer C A. Ferredoxins from two sulfonylurea herbicide monooxygenase systems in Streptomyces griseolus. Biochemistry. 1991;30:447–455. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parales J V, Parales R E, Resnick S M, Gibson D T. Enzyme specificity of 2-nitrotoluene 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42 is determined by the C-terminal region of the α subunit of the oxygenase component. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1194–1199. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1194-1199.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;158:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simons R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system of in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–790. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trower M K, Lenstra R, Omer C, Buchholz S E, Sariaslani F S. Cloning, nucleotide sequence determination and expression of the genes encoding cytochrome P-450soy (soyC) and ferredoxinsoy (soyB) from Streptomyces griseus. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2125–2134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Beilen J B, Wubbolts M G, Witholt B. Genetics of alkane oxidation by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Biodegradation. 1994;5:161–174. doi: 10.1007/BF00696457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallin B K, Condren A J. Fate of toxic and non-conventional pollutants in the wastewater treatment systems within the pulp, paper, and paperboard industry. EPA-600/2-81-158, NTIS PB81-247405. U.S. Washington, D.C: Environmental Protection Agency; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson A E J, Moore E R B, Mohn W W. Isolation and characterization of isopimaric acid-degrading bacteria from a sequencing batch reactor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3146–3151. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3146-3151.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanella E. The effect of pH on acute toxicity of dehydroabietic acid and chlorinated dehydroabietic acid to fish and Daphnia. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1983;30:133–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01610111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zon L I, Dorfman D M, Orkin S H. The polymerase chain reaction colony miniprep. BioTechniques. 1989;7:696–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]