Abstract

The molecular microevolution of the 23S rRNA gene (rrl) plus the spacer downstream has been studied by sequencing of different operons from some representative strains of the Escherichia coli ECOR collection. The rrl gene was fully sequenced in six strains showing a total of 67 polymorphic sites, a level of variation per nucleotide similar to that found for the 16S rRNA gene (rrs) in a previous study. The size of the gene was highly conserved (2902 to 2905 nucleotides). Most polymorphic sites were clustered in five secondary-structure helices. Those regions in a large number of operons were sequenced, and several variations were found. Sequences of the same helix from two different strains were often widely divergent, and no intermediate forms existed. Intercistronic variability was detected, although it seemed to be lower than for the rrs gene. The presence of two characteristic sequences was determined by PCR analysis throughout all of the strains of the ECOR collection, and some correlations with the multilocus enzyme electrophoresis clusters were detected. The mode of variation of the rrl gene seems to be quite similar to that of the rrs gene. Homogenization of the gene families and transfer of sequences from different clonal lines could explain this pattern of variation detected; perhaps these factors are more relevant to evolution than single mutation. The spacer region between the 23S and 5S rRNA genes exhibited a highly polymorphic region, particularly at the 3′ end.

The rRNA genes are the most frequently used markers for the study of molecular phylogeny for reasons that have been repeatedly reviewed (1, 30, 32), although their applicability to establish organismal phylogenies in prokaryotes has been recently contested (19, 26, 33). The rrn operons are among the few genes in prokaryotic genomes that are often repeated. In Escherichia coli seven rrn operons are located throughout the half of the chromosome containing the origin of replication (6). Little is known about the mode of evolution of these genes. A standard way to approach this problem is to study sequence variation within populations of relatively recent divergence, so that the general pattern of molecular evolution can still be discerned (31). Lately, we have studied the variation affecting different regions of the rRNA operons in E. coli and related species (2, 10, 22, 23), specifically, the rrs gene and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region between the rrs and rrl genes. As expected, relatively little variation of single nucleotide substitutions for the rrs gene was found, and higher variation for the rrs-rrl ITS was found. There were hypervariable regions in both elements where clustered nucleotide substitutions occurred, generally conserving the rRNA secondary structure (compensatory mutations). In some regions, such as helix V1 of the rrs gene, several variants were found. The different sequence variants differed by single or compensatory mutations, and possible relationships among the different sequences were shown (23). This mode of gradual change fits well with a model of evolution by neutral change and genetic drift. However, the most frequent situation in both the rrs gene and the rrs-rrl ITS (2) was the finding of a restricted number of highly divergent sequences that maintained the same secondary structure. This “jumpy” mode of variation is difficult to explain by neutral-change models. Sometimes the sequences found are similar to those of other species (5), and some researchers have suggested lateral transfer and recombination to explain their presence in E. coli. Regardless of their origin, molecular coevolution with ribosomal proteins or the transcript processing machinery could be an important reason for the preservation of these sequences (8).

The most remarkable difference found between the rrs gene and the rrs-rrl ITS was the presence in the latter of relatively large insertions and deletions, as exemplified by the rsl loop, that alter the secondary structure dramatically. A mode of evolution in which cumulative insertions and deletions would eventually alter the overall sequence of the rrs-rrl ITS was suggested (2, 22). This would explain the great variation found when organisms with increasing phylogenetic distances are compared, as opposed to the rrs gene, in which variation on a larger phylogenetic scale is relatively proportionate.

Here, we have studied another region within rRNA operons that includes the rrl gene and the spacer region downstream (rrl-rrf ITS). The rrl gene is apparently less restricted in size variation (11), and a wide divergence exist throughout the class Proteobacteria (21). In addition, the rrl gene is also assumed to be more variable at the sequence level than the rrs gene, particularly for shorter phylogenetic distances. Representatives from different clusters determined by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) of the E. coli ECOR collection (25), plus one O157 serotype isolate, were selected for sequencing. Hypervariable regions have been sequenced to assess intercistronic heterogeneity. Finally, the determined variants of two helices were examined by PCR analysis throughout the ECOR collection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation.

E. coli strains of the ECOR collection, comprising isolates from a wide variety of hosts and geographic regions (25), were used. Strain A8190 of E. coli serotype O157:H7 (kindly provided by T. S. Whittam, Pennsylvania State University) was also included. Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for 18 h at 37°C and stored at −80°C in 15% glycerol.

DNA extraction.

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted by using the InstaGene DNA Purification Matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s indications. DNA concentrations were spectrophotometrically estimated and diluted to 100 ng/μl.

PCR amplification.

Long-distance PCR was used to amplify the complete rrn operon and the upstream flanking sequence of ca. 1,000 bp. Previously described primers (2) designed on the basis of specific sequences located upstream of the rrs gene of E. coli K-12 were combined with primer 5SR (5′-ATGCCTGGCAGTTCCCTACT-3′). Reaction mixtures of 50 μl contained 1 μl of genomic DNA, 60 mM Tris-SO4 (pH 9.1), 18 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.8 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleotide, 0.2 μM each primer, and 2 U of Elongase Enzyme Mix (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies Ltd.). PCR was performed with a PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc.). The mixtures were subjected to 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 6 min. A final extension step of 68°C for 5 min was allowed. Probes designed on the basis of two variable regions of the rrl gene were H25R I (5′-CACACGCCTAAGCGTGCTCC-3′), H25R II (5′-CACCCCATTAAGAGGCTCCC-3′), and H25R III (5′-GTCACACAGATTGCTCTGTG-3′) for helix 25 and H63R I (5′-CAGCTCCATCCGCGAGGGAC-3′) and H63R II (5′-CAGCTCCACGAGCAAGTCGC-3′) for helix 63. The PCR conditions used with these probes were as previously described (2). PCR products were analyzed in 1% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized on a UV transilluminator.

Sequencing of the rrl gene and the rrl-rrf ITS.

PCR products were purified by using a QUIquick PCR Purification Kit (Quiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Nucleotide sequences were determined in an ABI PRISM 377 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer) as recommended by the manufacturer. The sequencing primers for the rrl gene were 23SOF (5′-GTGAGTCTCTCAAATTTTCG-3′), 23S3F (5′-AGTAGCGGCGAGCGAACGGG-3′), 23S6F (5′-GCGTACCTTTTGTATAATGG-3′), 23S8F (5′-ATAGCTGGTTCTCCCCGAAA3′), 23S11F (5′-AAGAAAGCGTAATAGCTCAC-3′), 23S16F (5′-TACCCCAAACCGACACAGG-3′), 23S20F (5′-TAGCGAAATTCCTTGTCGGG-3′), 23S23F (5′-GGGTAGTTGACTGGGGCGG-3′), and 23S26F (5′-CAAGGGTATGGCTGTTCGCC-3′). Primer 5SR was used to sequence the rrl-rrf ITS.

Data analysis.

Alignment and phylogenetic analysis of the rrl gene sequences were carried out by using the programs ClustalW and Mega (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, Version 1.01), respectively. Comparisons with sequences in the GenBank database were achieved by BLAST searches (BLASTN). The GenBank accession numbers of the rrl genes of strains ECOR 35, ECOR 52, ECOR 40, ECOR 10, ECOR 24, and A8190 are AF053963 to AF053968, respectively.

RESULTS

The six E. coli strains were subjected to locus-specific PCR using primers located upstream from each rrn operon. The strains were selected considering the diversity found in both the rrs gene and the rrs-rrl ITS (2, 23), as well as their relationships shown by MLEE (16). ECOR 10 is highly related to E. coli K-12 and was used as a reference. ECOR 24 was selected because it contains unusual intercistronic homogeneity and the rsl loop in all of the rrs-rrl ITSs. ECOR 35 is relatively homogeneous regarding differences among the rrn operons at the level of the rrs-rrl ITS. ECOR 40 belongs to an MLEE cluster with a peculiar insertion in the rrs-rrl ITS that is also found in Salmonella spp. and contains a high level of intercistronic heterogeneity. ECOR 52 is a representative of the MLEE B2 group that represents a highly homogeneous phylogenetic cluster that lacks the variants found in other MLEE clusters. Finally, A8190 is a representative of verotoxigenic E. coli serotype O157, which has recently been shown to be widely divergent from other E. coli lineages (27). PCR amplification yielded amplicons of ca. 6 kb. Complete rrl gene sequences of a single operon from each strain were determined in order to examine representatives of the operons containing one (rrnC and rrnB) and two (rrnD) tRNA genes. Figure 1 summarizes the 67 polymorphic sites found from alignment of the six rrl genes fully sequenced. The pattern of variation was highly reminiscent of that found for the rrs gene (23), and the percentage of polymorphic sites is about the same. All of the rrl genes were almost identical in size, 2902 to 2905 bp. Intervening sequences, like those found in Salmonella rrl genes (4), were not detected. They were not found in the rrs genes of E. coli strains (5, 23) either, and if they are present at all in E. coli, they should be much rarer than in Salmonella spp.

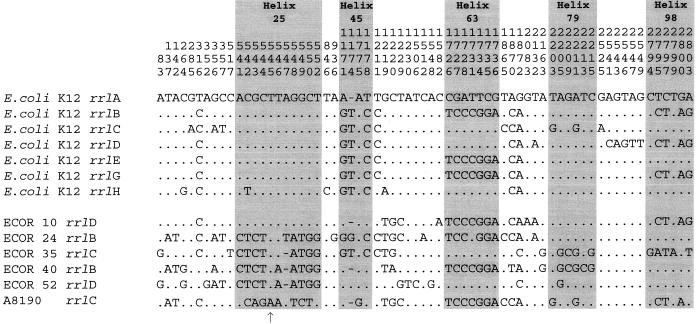

FIG. 1.

Variable positions in the rrl genes of E. coli K-12 and other strains used in this study. Periods indicate the same nucleotide composition as the rrlA sequence of E. coli K-12 (Escherichia coli Database Collection). The numbers at the top indicate positions in the sequences reported by Brosius et al. (3). Insertion of nucleotides G and C between positions 545 and 546 is indicated by the arrow.

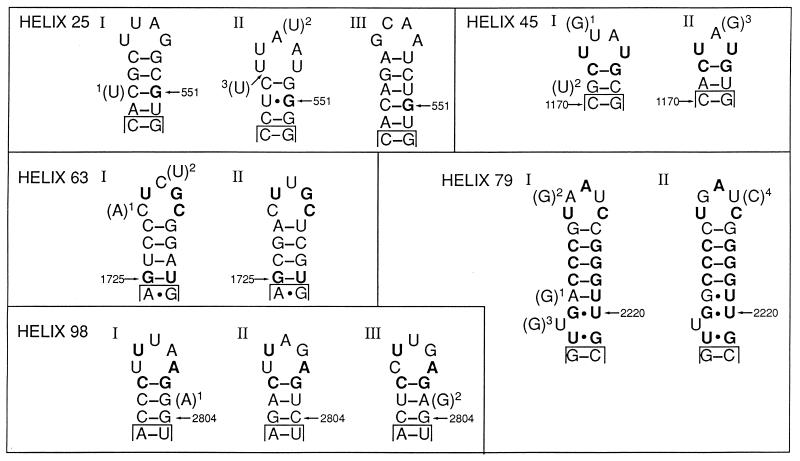

Most polymorphic sites clustered in five secondary-structure loops, viz., helices 25, 45, 63, 79, and 98 (helix numbering is that of Larsen [20]; Fig. 1 and 2). In helices 25, 63, and 98, although the secondary structure is well preserved, the sequence is often remarkably divergent. A moderate degree of polymorphism was observed in helices 45 and 79, and some intermediate forms could be related by single and compensatory mutational events. In helix 25, the three forms detected had a distribution clearly associated with the MLEE clusters. Partial sequences of the most variable regions were obtained from a larger number of rrn operons of the six strains previously amplified by PCR using operon-specific primers. The types of primary structures detected are summarized in Table 1. These sequencing results confirmed the polymorphism already found in the fully sequenced rrl genes; no new forms were detected in the hypervariable helices under study (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Except for helices H25 II, H25 III, and H98 II, all of the structures were previously found in E. coli K-12 (data from the Escherichia coli Database Collection). A remarkable aspect of the results presented in Table 1 is the high degree of intercistronic homogeneity found within each strain. This homogeneity has been confirmed by a PCR test using specific probes for helix 25 and, to a lesser degree, helix 63 (Fig. 3). E. coli K-12 and strain ECOR 10 (which are highly related) were the most heterogeneous, in agreement with previous analysis of the rrs gene (23) and the rrs-rrl ITS (2).

FIG. 2.

Secondary structures of variable regions in the rrl genes from E. coli strains. The numbers indicate positions reported by Brosius et al. (3). Conserved nucleotides are in boldface. In parentheses are the nucleotides that have been determined in the rrl genes of the following strains: helix 25, (U)1 in rrlH of ECOR 40, (U)2 in rrlB, rrlC, rrlE, and rrlG of ECOR 35, and a (U)3 insertion in rrlB, rrlC, and rrlD of ECOR 24 and rrlG of A8190; helix 45, (G)1 in rrlB, rrlG, and rrlH of ECOR 10 and rrlB, rrlC, and rrlD of ECOR 24, (U)2 in rrlC of ECOR 24; and (G)3 in rrlA and rrlC of A8190; helix 63, (A)1 in rrlC of ECOR 40 and (U)2 in rrlB and rrlC of ECOR 10 and rrlB, rrlC, and rrlD of ECOR 24; helix 79, (G)1 in rrlA, rrlC, rrlD, and rrlE of ECOR 52 and (G)2 and (G)3 in rrlB and rrlC of ECOR 10 and rrlA, rrlC, and rrlG of A8190; helix 98, (A)1 in rrlC of A8190 and (G)2 in rrlA and rrlE of ECOR 52.

TABLE 1.

Determination of variable regions in the rrl genes of the ECOR collection strains used in this study and E. coli K-12

| Strain and locus | Sequence present ata:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helix 25

|

Helix 45

|

Helix 63

|

Helix 79

|

Helix 98

|

||||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | I | II | I | II | I | II | III | |

| K-12 | ||||||||||||

| rrlA | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlB | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlD | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlE | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlG | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlH | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| ECOR 10 | ||||||||||||

| rrlB | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlD | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlG | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlH | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| ECOR 24 | ||||||||||||

| rrlB | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlD | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| ECOR 35 | ||||||||||||

| rrlB | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlE | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlG | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| ECOR 40 | ||||||||||||

| rrlB | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| ECOR 52 | ||||||||||||

| rrlA | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlD | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlE | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| A8190 | ||||||||||||

| rrlA | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlC | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlE | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| rrlG | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

A plus sign indicates the sequence found at the locus and helix in question.

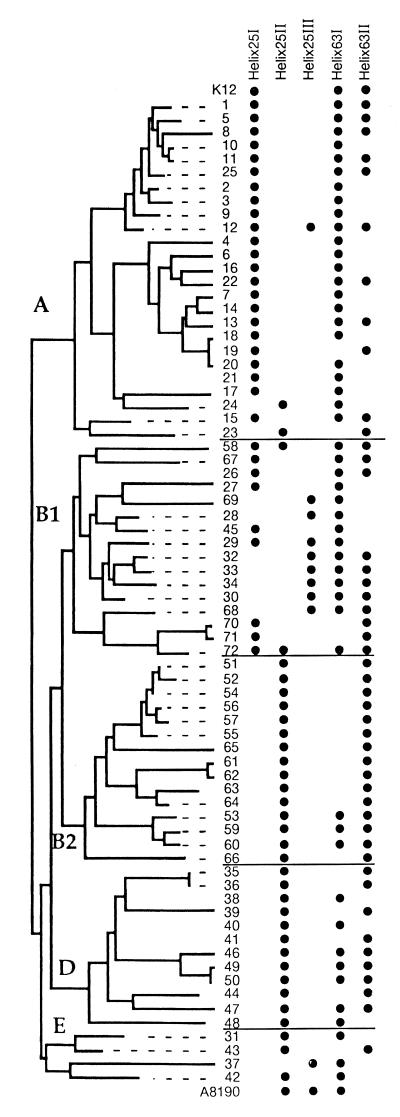

FIG. 3.

Distribution of structures I, II, and III of helix 25 and structures I and II of helix 63 among the ECOR strains as revealed by a PCR test using sequence-specific probes. The MLEE relationships shown in the tree are those described by Herzer et al. (16) modified by the addition of E. coli K-12 and A8190.

For helices showing widely divergent sequences (helices 25 and 63), PCR primers were designed and used as probes to screen the ECOR collection in order to evaluate their distribution throughout the phylogenetic expanse of the species (Fig. 3). The sequence of helix 25 I, found in E. coli K-12, was restricted to MLEE cluster A plus two strains of B1. The probe for ECOR 25 II hybridized with most of the strains of groups B2, D, and E. Altogether, the distribution of these different forms seemed to correlate quite well with the clusters defined by MLEE. Finally, the probe for the sequence of helix 25 III, found originally in strain A8190, was restricted to a group of strains within cluster B1 of MLEE and only two strains outside this cluster, ECOR 12 of cluster A and ECOR 37 of cluster E. All of the other representatives of group E were negative with this probe. In a previous study of mdh sequences using representatives of E. coli, only ECOR 37 fell within the cluster that includes representatives of the O157:H7 serotype (27). Only four strains in the ECOR collection were positive by more than one H25 probe, showing remarkable intercistronic homogeneity at this level. A different result was obtained with probes for the two sequences found in helix 63. Twenty-five strains were positive with both probes, 25 were positive only by the probe for helix 63 I (half of them belonging to group B2), and the remaining 22 strains were positive only by the helix 63 II probe. In this case, intercistronic heterogeneity must be as high as that of E. coli K-12 (Table 1).

The sequences found in the hypervariable loops were compared to those in databases to assess similarity to the equivalent loops in other bacterial species. No significant match was found, with the single exception of helix 98 II, which was most similar (only two nucleotides were different) to the equivalent helix of Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, the tetranucleotide (AACG) at the end of helix 25 III was found in many members of the class Proteobacteria, including Thiobacillus cuprinus, Nannocystis exedens, and Stigmatella aurantica.

23S-5S rRNA gene ITS region (rrl-rrf ITS).

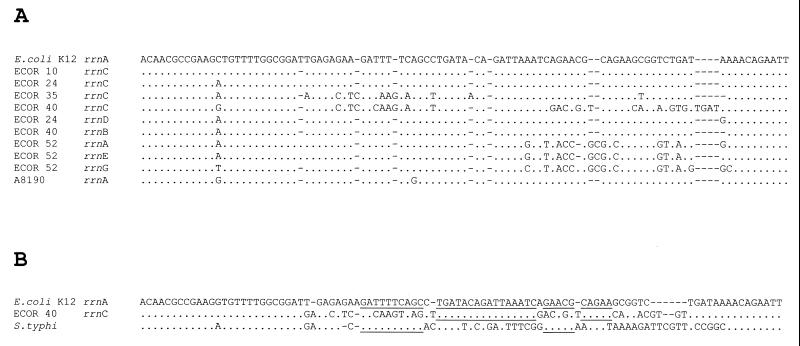

This spacer region is highly conserved among the rrn operons of E. coli K-12. In this strain, 57 of the 94 nucleotides of this ITS are presumed to form a secondary structure by pairing with the corresponding stretch downstream of the 5S rRNA gene (rrf) (3). However, strains in the present study showed significant variations affecting mostly the region that does not contribute to the secondary structure of the transcript (Fig. 4A). Particularly, one of the operons of ECOR 40 (group D) and the three operons of ECOR 52 (group B2) are widely divergent from E. coli K-12 in their rrl-rrf ITS sequences. A remarkable intercistronic heterogeneity was found affecting the determined rrl-rrf ITS of ECOR 40.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of rrl-rrf ITS sequences determined for ECOR strains and A8190 and for rrnA of E. coli K-12. (B) Alignment of rrl-rrf ITSs of E. coli K-12, ECOR 40, and S. typhi. Mosaic similarities are underlined. Periods indicate the same nucleotide composition.

DISCUSSION

23S rRNA gene.

Overall, the sequence variation found in the rrl gene was smaller than expected. The 23S rRNA gene is larger and shows a higher rate of variation than does the rRNA of the small subunit (11, 18). When different genera of the class Proteobacteria are compared, the similarity of the 16S rRNA genes is about 4% higher than that of the 23S rRNA genes (21). In a previous study (23), five complete rrs gene sequences from three strains in the ECOR collection showed 34 polymorphic sites (unpublished data). In the present study, 67 polymorphic sites were detected in the six fully sequenced rrl genes. Therefore, at this level, variation per nucleotide seems to be equivalent for both genes. Similarly, an unexpected conservation was found for the size of the rrl gene. Even disregarding the contribution of frequent intervening-sequence insertions, the size of the 23S rRNA molecule in members of the class Proteobacteria varies in a range of ca. 200 nucleotides (21). The size of the rrl genes within the ECOR collection varied by only three nucleotides; apparently, as happens with the spacer regions (2, 22), variability at the interspecific level cannot be used to infer intraspecific variability.

On the other hand, the hypervariable regions found correspond to the variable loops detected by sequence comparison of rrl genes from widely divergent Proteobacteria. Helices 25, 63, and 98, which contained most of the variable sites, are also the most variable helices at the level of different proteobacterial subclasses. This could be interpreted as just a reflection of the low functional restriction of these regions of the secondary structure. However, the pattern of variation found in these helices does not fit well with a model of neutral variation by genetic drift (14). In the latter, a more gradual variation should be expected (15). Instead, we found alternative sequences that are not similar but are apparently well preserved among strains. Some of the sequences found in these helices are not completely unique to E. coli. For example, the nonpaired nucleotide stretch at the end of helix 25 III was identical to that of distantly related genera of Proteobacteria. However, the small number of identical nucleotides seems to indicate that this reflects common ancestry and functional conservation rather than horizontal transfer. In helix 98 II, a nearly identical sequence for the whole loop is found in K. pneumoniae. In this case, horizontal transfer seems more likely given the high similarity over a wide stretch of nucleotides and the close relationship between the two species. Still, other regions seem to vary according to a gradual pattern. The sequence diversity found in helices 45 and 79 could easily have originated from single and compensatory mutations affecting these areas, and the same applies to the isolated nucleotide substitutions. In all of these aspects, the rrl gene is reminiscent of the rrs gene, where hypervariable regions of both types have been found (23).

In the rrs gene, intercistronic heterogeneity in two variable regions was rampant, and most strains contained more than one of the sequence types detected (23). Something similar happens in helix 63 of the rrl gene. However, intercistronic heterogeneity seems to be rather restricted in helix 25. As detected by sequencing and probing by PCR, most strains, including E. coli K-12 and ECOR 40, seem to have only one of the sequence types found, although both strains are particularly heterogeneous in other regions of the operon (2, 23). The distribution of sequence types for helix 25 follows the MLEE phylogeny quite well. For instance, helix 25 I seems characteristic of group A, and strains of clusters B2 and D only showed helix 25 II. The clonality of cluster B2 was also evidenced by a previous analysis of rrs sequence diversity (23).

23S-5S rRNA gene ITS region (rrl-rrf ITS).

Sequencing of the rrl-rrf ITS has revealed the existence of an undescribed hypervariable region affecting ca. 40 nucleotides before the 5′ end of the rrf gene (Fig. 4A). This region seems to be the most variable found throughout the rrn operon. We have found again a strong heterogeneity affecting ECOR 40, a strain that is highly heterogeneous in the rrs gene and the rrs-rrl ITS (2, 23). The mosaic relationships found in the spacer regions of E. coli K-12, ECOR 40, and S. enterica serovar typhi are remarkable (Fig. 4B). This situation is often found in comparisons of homologous genes of bacteria (9, 24, 28), and it has generally been attributed to recombination. However, recombination acting over such short stretches of nucleotides appears unlikely. In spite of the wide variation at the nucleotide sequence level, the size of the spacer was remarkably conserved for the strains sequenced. This is in contrast to the rrs-rrl ITS, where size varies widely, even among orthologous (containing the same tRNA gene) operons (3).

Molecular evolution of the rrn operons in E. coli.

Only restricted information regarding the sequence diversity in roughly half of the ribosomal operons studied here is available, because only the hypervariable regions were sequenced in more than one operon per strain. However, from the partial sequences and the PCR probe screening, it is quite apparent that this section of the ribosomal operon behaves similarly to the other half. The information accumulated regarding the sequence variation in different strains of the ECOR collection allows us to draw a general picture of how the evolution of the operon has proceeded. As expected, variation is concentrated in specific regions, and the sequence variation preserves the secondary structure (i.e., covariation) (13). This much can be predicted from what is known about the variation at the interspecific level. However, there are two markedly different modes of variation. One is exemplified by helix V1 of the rrs genes or helices 79 and 45 of the rrl genes that exhibit a gradual variation that could be explained by a lack of functional restriction and genetic drift. Other regions, such as V6 of rrs genes or helices 25, 63, and 98 of rrl genes only showed a few different, widely divergent sequence types, but no gradual variation was present. In the latter, a high level of similarity to the equivalent region in other bacterial species is sometimes found. These widely divergent variations could have originated by mutation or by horizontal transfer. In any case, the lack of gradual variation among the ECOR representatives studied hints of a more restricted freedom of variation by functional restriction and/or coevolution with ribosomal proteins. The spacer regions vary in a similar pattern, with relatively few isolated nucleotide substitutions and most of the polymorphisms clustered in areas that sometimes also correspond to conserved secondary-structure loops. The rrs-rrl ITS contains important insertion and deletion events that are not found in the structural genes and could be the main force behind the wide divergence found when spacers from distantly related species are compared.

Another aspect of the evolution of the rrn operons is intercistronic heterogeneity. The concerted evolution of the rRNA gene family has been shown to be essential in eukaryotes for the relatively slow rate of change of those genes and noncoding sequences (18). The resulting effect of molecular drive has been suggested to be an important force in evolution in general and in the maintenance of species coherence and even identity, i.e., low (or negligible) levels of intraspecific variation versus notable interspecific variation (7, 8). Based on the available preliminary analysis, intercistronic and intraspecific variation of the rRNA genes appears to be very small in those organisms (17). On the other hand, a more limited number of copies of the repeating units is present in prokaryotes (1 to 13 rrn operons) (12) than in eukaryotes (typically in the range of hundreds). In addition, the panmictic structure found for most diploid multicellular eukaryotic populations cannot be extrapolated to bacterial populations (29). In fact, the degree to which different bacterial species differ from panmixia is a subject of ongoing controversy and is one of the keys to a better understanding of bacterial population genetics. In principle, smaller numbers of gene copies and more clonal (further from panmixia) populations should lead to more intercistronic and intraspecific variation and, in the absence of strong purifying selection (such as those predicted for spacer regions), to faster evolutionary rates. Indeed, the levels of intercistronic heterogeneity and intraspecific variation seem to be higher in bacteria. While as far as we know, E. coli strains have the same number of copies of the rrn operons, different situations are apparent in different strains. For example, E. coli K-12 and ECOR 40 are remarkably heterogeneous at the level of the entire operon. In contrast, strains in MLEE cluster B2, which includes strains that cause urinary tract infections, are much more homogeneous, reflecting either their inability to recombine with DNA from distantly related strains or a restricted ecological niche.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adoutte A, Philippe H. The major lines of metazoan evolution: summary of traditional evidence and lessons from ribosomal RNA sequence analysis. EXS. 1993;63:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7265-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antón A I, Martínez-Murcia A J, Rodríguez-Valera F. Sequence diversity in the 16S-23S intergenic spacer region (ISR) of the rRNA operons in representatives of the Escherichia coli ECOR collection. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:62–72. doi: 10.1007/pl00006363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosius J, Dull T J, Sleeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgin A B, Parodos K, Lane D J, Pace N R. The excision of intervening sequences from Salmonella 23S ribosomal RNA. Cell. 1990;60:405–414. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cilia V, Lafay B, Christen R. Sequence heterogeneities among 16S ribosomal RNA sequences, and their effect on phylogenetic analyses at the species level. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:451–461. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condon C, Liveris D, Squires C, Schwartz I, Squires C L. rRNA operon multiplicity in Escherichia coli and the physiological implications of rrn inactivation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4152–4156. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4152-4156.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dover G A. Observing development through evolutionary eyes: a practical approach. Bioessays. 1992;14:281–287. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dover G A, Flavell R B. Molecular coevolution: DNA divergence and the maintenance of function. Cell. 1984;38:622–623. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBose R F, Dykhuizen D E, Hartl D L. Genetic exchange among natural isolates of bacteria: recombination within the phoA gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7036–7040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Martínez J, Martínez-Murcia A J, Antón A I, Rodríguez-Valera F. Comparison of the small 16S to 23S intergenic spacer region (ISR) of the rRNA operons of some Escherichia coli strains of the ECOR collection and E. coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6374–6377. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6374-6377.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray M W, Schnare M N. Evolution of the modular structure of rRNA. In: Hill W E, Dahlberg A, Garrett R A, Moore P B, Schlessinger D, Warner J R, editors. The ribosome: structure, function, & evolution. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurtler V, Stanisich V A. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3–16. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutell R R. Collection of small subunit (16S- and 16S-like) ribosomal RNA structures: 1994. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3502–3507. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutell R R, Larsen N, Woese C R. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:10–26. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.10-26.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock J M, Tautz D, Dover G A. Evolution of the secondary structures and compensatory mutations of the ribosomal RNAs of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol. 1988;5:393–414. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzer P J, Inouye S, Inouye M, Whittam T S. Phylogenetic distribution of branches RNA-linked multicopy single-stranded DNA among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6175–6181. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6175-6181.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillis D M, Davis S K. Ribosomal DNA: intraspecific polymorphism, concerted evolution, and phylogeny reconstruction. Syst Zool. 1988;37:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillis D M, Moritz C, Porter C A, Baker R J. Evidence for biased gene conversion in concerted evolution of ribosomal DNA. Science. 1991;251:308–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1987647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koonin E V, Galperin M Y. Prokaryotic genomes: the emerging paradigm of genome-based microbiology. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:757–763. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen N. Higher order interactions in 23S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5044–5048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludwig W, Rosello-Mora R, Aznar R, Klugbauer S, Spring S, Reetz K, Beimfohr C, Brockmann E, Kirchhof G, Dorn S, Bachleitner M, Klugbauer N, Springer N, Lane D, Nietupsky R, Weizenegger M, Schleifer K H. Comparative sequence analysis of 23S rRNA from Proteobacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:164–188. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luz S P, Rodríguez-Valera F, Lan R, Reeves P R. Variation of the ribosomal operon 16S-23S gene spacer region in representatives of Salmonella enterica subspecies. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2144–2151. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2144-2151.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martínez-Murcia, A. J., A. I. Antón, and F. Rodríguez-Valera. Patterns of sequence variation in two regions of the 16S rRNA multigene family of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Milkman R. Recombinational exchange among clonal populations. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2663–2684. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochman H, Selander R K. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:690–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.690-693.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennisi E. Genome data shake tree of life. Science. 1998;280:672–674. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pupo G M, Karaolis D K R, Lan R, Reeves P R. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strains inferred from multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and mdh sequence studies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2685–2692. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2685-2692.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selander R K, Li J, Boyd E F, Wang F-S, Nelson K. DNA sequence analysis of the genetic structure of populations of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli. In: Priest F G, et al., editors. Bacterial diversity and systematics. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith J M. Population genetics: an introduction. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2685–2690. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sogin M. Early evolution and the origin of eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1991;1:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tautz D, Tautz C, Webb D, Dover G A. Evolutionary divergence of promoters and spacers in the rDNA family of four Drosophila species. Implications for molecular coevolution in multigene families. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:525–542. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woese C R. The universal ancestor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6854–6859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]