Abstract

Background

In the coronavirus disease-impacted era, many medical institutions have not permitted clinical practice at hospitals or have operated their training on a restricted basis. The effective strategy for improving therapeutic communication and team cooperation as a nursing core competency is required.

Objectives

The study aimed to verify the effects of simulation problem-based learning on nursing students' communication skills, communication attitudes, and team efficacy.

Design

Non-equivalent control group pretest-posttest design.

Settings

A university in South Korea.

Participants

Nursing students who were classified as advanced beginners were randomly allocated to the control group (n = 46) or the experimental group (n = 47).

Methods

The experimental group's students participated in the simulation problem-based learning for cesarean section maternity nursing. The control group's students participated in a conventional type of maternity nursing clinical practice. The communication skills, communication attitudes, and team efficacy were measured by using a self-reported questionnaire.

Results

As compared with the pretest, the communication attitudes increased significantly (t = 2.41, p = .020) in the posttest for the experimental group. The communication skills (t = 1.47, p = .150) and team efficacy (F = 3.30, p = .073) were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

The simulation problem-based learning in clinical practice is recommended to improve communication attitudes for nursing students and to apply the learned knowledge in simulated nursing situations through experiential learning. Future research is particularly needed the standardized educational program to identify the long-term effects in various cases and settings.

Keywords: Cesarean section, Communication skills, Communication attitudes, Team efficacy, Maternity nursing, Simulation problem-based learning

1. Introduction

Patients' symptoms are becoming diverse, complex, and severe, rather than typical. This increases the need for nurses' communication with patients to achieve an optimal nursing outcome (Kim, 2014; Lasater, 2007). Considering that nursing is a discipline that prioritizes human-to-human relationship, it is critical for nurses and patients to build therapeutic relationships between them (Travelbee, 1971). Nurses are required to engage in therapeutic communication with patients to facilitate their interactions (Bambini et al., 2009; Ruth and Constance, 2007). As a part of the nursing education program offered by the Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education, such therapeutic communication is one of the core competencies that nursing students in a baccalaureate program must learn through integrated practical training (Yang and Hwang, 2016).

However, with the emergence of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China in 2019, and its continued existence in Korea since January 20, 2020, local communities have seen a rapid spread of the infection. Many medical institutions have not permitted clinical practice at hospitals or have operated their training on a restricted basis (Kang, 2020). As a result, the nursing students seeking to become professional nurses are finding it difficult to learn core competencies including communication based on therapeutic relationships through only traditional clinical practice in the COVID-19 pandemic. Especially, these competencies may be acquired effectively through direct interaction with patients or high-fidelity human patient simulators, not by simply participating in a limited clinical practice (Lee et al., 2007).

To complement the limited experiential learning of traditional clinical practice, simulation is being used more frequently in nursing education (Blum et al., 2010). In particular, there is a growing need to supplement the experience of interaction between the nursing students and patients with applying simulation problem-based learning (S-PBL) (Son, 2020). This is linked to nursing simulation and problem-based learning (PBL), and its effectiveness is validated. Simulation is a technique to replace real-patient experiences with supervised and guided experiences, artificially contrived to evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner (Gaba, 2004). Moreover, PBL is an alternative educational method that was first suggested in the medical field to overcome one of the problems of traditional medical education—the failure to develop the problem-solving ability required in clinical settings (Barrows, 1994). PBL is specifically effective in promoting communication between patients and nurses caused by a lack of experience (Yuan et al., 2019), thus PBL could be used to overcome limitations with clinical practice at hospitals (Shin and Kim, 2013). In this context, S-PBL employs standardized patients and simulators to replicate the conditions that are similar to real-world clinical settings. It is useful in teaching strategies that allow nursing students to learn by repetition, obtain feedback, receive evaluation, and reflect on themselves. It also helps them integrate their theoretical and practical learning (Bland et al., 2011; Cato et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2019).

Given the past research, S-PBL also uses peer role-play and offers real-world experience and training for health communication and collaboration. With an increasing focus on patient safety and quality care, finding innovative ways to better educate nursing students in the use of therapeutic communication are being seen as important (Campbell et al., 2013). Professional communication between nurse and patient has a significant role in patient satisfaction with nursing care (Lotfi et al., 2019). This communication is actually used in hospitals among physicians, nurses, patients, and carers. In other words, communication refers to the sharing of health-related information between them. Each stakeholder acts as both a sender and a receiver. It specifically refers to exchanging information verbally, nonverbally, in writing, or in conversation (Yang and Hwang, 2016). In nursing education, communication skills mean that performed verbal or nonverbal health communication behaviors between nursing students and patient, and communication attitudes is nursing students' perceptions of communication effectiveness (Campbell et al., 2013; Rees et al., 2002). However, there is evidence to suggest that communication skills and attitudes decline as students' progress through their training (Rosenbaum, 2017). Furthermore, nurses work in a team with other healthcare professionals as well as nurses. Team efficacy is required to perform a variety of nurses' roles to deliver patient-centered care and achieve nursing outcomes by collaborative practice (Kim et al., 2011). Team efficacy refers to a team's belief that it can successfully perform a specific task (Lindsley et al., 1995). Team efficacy is not simply the sum of the efficacy beliefs of individual members (Bandura, 2000). Members must coordinate their actions, and they are likely to be influenced by the beliefs, motivation, and performance of their coworkers (Gully et al., 2002). Simulation provides excellent opportunities for learning assessment and evaluation of group dynamics in nursing students' interactions in clinical environments (Campbell et al., 2013). Therefore, to increase nursing students' non-technical skills such as communication and team efficacy, this study was used S-PBL by peer-role plays based on Peplau's (1952) interpersonal relationship theory.

Peplau's (1952) Interpersonal Relationship Model is a mid-range, descriptive classification theory focusing on the interpersonal relationships between nurses and patients to solve their health-related problems (Fawcett, 2005; McCamant, 2006). It is ideal for situations that require communication in various interpersonal relationships. It has also been empirically verified to be sufficient through the assessment and evaluation of the different communication aspects in clinical settings (Erci et al., 2008; Oh, 2005). Since the publication of the Interpersonal Relationship Model in 1952, the model has been applied to the development of nursing education, practice, theory, and research (Oh, 2005). Therefore, this study develops nursing scenarios by using peer role-plays based on Peplau's (1952) model. It implements this for nursing students as a part of their educational program. This study seeks to provide nursing students with opportunities to engage in interpersonal communication. This communication is based on the interpersonal relationships among nurses, medical staff, patients, and carers that may be encountered in nursing situations. The study also seeks to identify its impact on nursing students' communication skills, communication attitudes, and team efficacy.

1.1. Aims

The study's purpose was to determine the effects of a practical course integrated with S-PBL for Cesarian section (C-section) maternity nursing on nursing students' communication skills, communication attitudes, and team efficacy.

1.2. Research hypotheses

The study's hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1

The nursing students who participated in S-PBL will exhibit improved communication skills as compared to the nursing students who participate in the conventional clinical practice.

Hypothesis 2

The nursing students who participated in S-PBL will exhibit improved communication attitudes as compared to the nursing students who participated in the conventional clinical practice.

Hypothesis 3

The nursing students who participated in S-PBL will exhibit improved team efficacy as compared to the nursing students who participated in the conventional clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

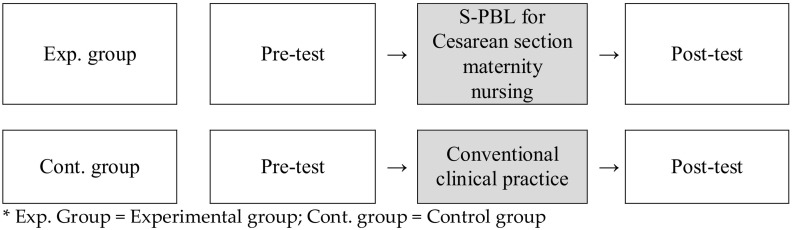

A quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group pretest and posttest designs are shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Research design.

Exp. group = Experimental group; cont. group = Control group.

2.2. Participants and setting

The participants of this study were selected by convenience sampling of third-year nursing students participating in a maternity nursing practicum at a single university in South Korea's “S City” (a metropolitan area). Nursing students who understood the purpose of this study during the subject orientation and voluntarily agreed to participate were selected. Before becoming eligible for this study, the participants were required to take basic courses in human relations and communication, and prerequisite courses in maternity nursing.

Using the G*Power 3.1 program, the minimum number of the samples were calculated based on a significance level α of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and an effect size of 0.8 (Son, 2020). This yielded a minimum number of 42 samples for each group, which is a total of 84. The sample was randomly assigned to the experimental group (n = 47) and the control group (n = 46) by considering a dropout rate of 10%. When one person from each group was eliminated due to responding insincerely, 91 students were eligible to participate. This therefore met the minimum sample size.

2.3. Outcome assessment

2.3.1. Communication skills

The communication skills were measured by using the Korean version of the Health Communication Assessment Tool (K-HCAT). HCAT is a communication assessment tool developed by a collaboration between the nursing and communication scholars. The aim is to measure the nursing students' communication skills in clinical simulation with standardized patients or simulators (Campbell et al., 2013). The K-HCAT consists of 15 items that are answered by using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from one to five points. The reliability Cronbach's ⍺ was 0.80 to 0.91 (Campbell et al., 2013). The K-HCAT's Cronbach's ⍺ was 0.85 (Yang and Hwang, 2016), whereas in the present study, it was 0.81.

2.3.2. Communication attitudes

The nursing students self-assessed their communication attitudes by using the Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS). This was designed by Rees et al. (2002) for medical students. The CSAS consists of 26 items that measured the recognition of communication value, learning modalities, and continuous learning efforts. It has 13 positive and 13 negative questions on the respondents' competencies in communication. Each question is answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). The higher the total score, the greater the importance of the communication. The Cronbach's ⍺ for Rees et al. (2002) ranged from 0.81 to 0.87, whereas in the present study, it was 0.81.

2.3.3. Team efficacy

The team efficacy was measured by using a tool developed by Marshall (2003). It was modified and supplemented by Kwon (2010). It consists of a total of 8 items, each of which is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from one ‘not at all,’ to five ‘very much so.’ The higher the score, the more effective the team. The Cronbach's α for Kwon's (2010) study was 0.97, whereas in the present study, it was 0.81.

2.3.4. Development of simulation problem-based learning

The S-PBL for C-section maternity nursing was developed based on Peplau's (1952) Interpersonal Relationship Model. Peplau (1988) suggested that the nurse-patient relationships are formed in four stages: orientation, identification, exploitation, and resolution. The S-PBL was designed to allow for the implementation of obstetric nursing after C-section, with each step interlocking and overlapping with each other (Fig. 2 ). This was because each phase overlapped with one another and was linked to the other phases.

Fig. 2.

Research framework based on Peplau's Interpersonal Relationship Model.

The S-PBL began with the orientation phase, where the nursing students met patient about to undergo C-section, along with their carer. The nursing students greeted the patient and carer by name and with professional title. They initiated communication with them. This allowed students to provide nursing information to the patient after cesarean delivery. It also allowed them to establish trust and rapport through their skilled nursing assessments. During the identification phase, nursing students identified their nursing needs to generate a nursing diagnosis. This was an important part of continuing and developing the therapeutic relationships with the patient and carer from the previous phase. Through the exploitation phase, the nursing students, patient, and carer formed an effective therapeutic relationship. In S-PBL, the therapeutic communication for counseling and education, or implementation were provided a platform to aid the patient in solving their problems. Through these interactions, the trust relationships with the patient were developed. The resolution phase allowed the nursing students to resolve their nursing problems and reflect back on the care provided. The nursing students were responsible for providing additional information and advice, and appropriate support to the patient. At this stage, if the nursing assessment identified the patient's new nursing needs, the nursing students were able to promise and plan new interactions to address these inadequacies.

At every stage, the three nursing techniques for the interpersonal processes presented by Peplau were included: observation, verbal and nonverbal communication, and recording (Peplau and Ebrary, 1991). The observations focused on assessing the physical and psychological well-being of the patients who came to the ward after a cesarean delivery had been performed, and predicting what they needed. Verbal or nonverbal communication involved a professional nurse building trust by communicating clear information to the patients. It also involved identifying the nursing needs and resolving nursing problems. These include anxiety and pain derived from the patients' various expressions, such as facial expressions. Records involved documenting the nurses' performance, the patients' responses, and so on. It encouraged students to express their opinions on the S-PBL during the debriefings through the reflection journaling.

The S-PBL for C-section maternity nursing was developed by two nursing professors, who were in charge of more than a decade of maternal nursing clinical experience. They also were responsible for more than five years of maternal nursing lecture and practice. The learning objective was to help the nursing students to gain confidence through their ability to establish therapeutic relationships with the patient and to resolve nursing problems during the C-section maternity nursing.

2.4. Research procedures

The nursing students, who were eligible participants in this study, had to complete a maternal nursing course, a prerequisite subject. They also had to gain basic knowledge about the C-section maternity nursing. In small groups of three to four students, students were randomly assigned to control or experimental groups using drawing lots according to the duration of the maternal nursing practicum.

The control group was exposed to communication in clinical nursing situations through the conventional clinical practice. The experimental group was provided with opportunities to communicate with other nursing students by reenacting clinical nursing situations in the small group activities of S-PBL. The nursing students in the experimental group engaged in the nursing activities associated with S-PBL for C-section maternity nursing based on their major knowledge. Students were provided with a prebriefing for 50 min, during which they were guided on the topic of C-section maternity nursing and the S-PBL. They were given sufficient time for group discussions prior to participation in the S-PBL. The students then were arranged to observe through a one-way mirror and participated in the small group activities during the S-PBL. They also practiced the C-section maternity nursing in a simulation room that replicated the clinical environment by using a high-fidelity human patient simulator. The activities were designed such that a group of three to four randomly selected students had to analyze the nursing cases presented by the instructors. They also had to derive nursing problems to perform the C-section maternity nursing. Fifteen minutes of the S-PBL's running time was applied to each group. After running a simulation, the instructor evaluated the students' nursing performance by using a checklist related to the C-section maternity nursing. A 50-minute debriefing followed, where the instructor relayed feedback to the students in the evaluation of the results and reflection.

2.5. Data collection

From May 24 to July 16, 2021, the study was conducted with nursing students enrolled in the maternal nursing practice course. It was ensured that the nursing students were not aware of their placement in an experimental or control group. They were kept from interacting with each other during the intervention and data collection period by varying the time and location, so as to avoid the diffusion or imitation effect of treatment. Prior to the study, the researcher provided a comprehensive explanation of the study to the participants for voluntary participation. The data collection for the pre- and post-surveys each took approximately 10 min per survey. The students were required to complete the structured questionnaires individually by using the KSDC database online survey platform (https://www.ksdcdb.kr) to prevent the exposure to personal information and the evaluators biases. The researchers compensated all the participants with school supplies worth KRW 1000.

2.6. Statistical analysis

For the data analysis, the IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 program (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the general characteristics. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to assess the reliability of the instruments. Regarding the effect of interventions, a paired t-test was used to analyze the communication skills and attitudes with homogeneous pre-values. An ANCOVA was used to analyze the team efficacy without homogeneous pre-values. The correlation between the factors indicated the size of the correlation coefficient. This was considered statistically significant if the p-value was <0.05.

2.7. Ethical considerations

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the research ethics review committee at the university where the researcher was affiliated. The participants were free to express their intention to participate or decline to participate in the study at any time. We eliminated unnecessary tension regarding their participation by explaining in detail, prior to the study's commencement. No negative effects were associated with refusing to participate. The researchers informed the nursing students that if they experienced new stress while completing the survey, researchers would provide appropriate empathy and communication separately. To protect participants' privacy, an online platform was used for the survey.

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity test

Table 1 shows the homogeneity test's results for the general characteristics and variables of the experimental and control groups. In all the categories both groups were statistically homogeneous: average age (t = 1.30, p = .199), gender (X2 = 0.13, p = .758), religion (X2 = 2.38, p = .304), self-rated health (X2 = 4.03, p = .133), reason for majoring in nursing (X2 = 3.60, p = .609), GPA (X2 = 0.96, p = .810), residential status (X2 = 7.83, p = .050), and satisfaction in major (X2 = 5.34, p = .149). For the variables, the two groups were not statistically homogeneous regarding the team efficacy (t = −2.61, p = .011). They were homogeneous in the communication skills (t = −1.74, p = .087) and communication attitudes (t = −0.01, p = .925).

-

Hypothesis 1: The nursing students who participated in the S-PBL will exhibit improved communication skills as compared to those who participated in the conventional clinical practice.

The experimental group's communication skills increased from a pre-simulation average score (SD) of 61.52 ± 10.54 to a post-simulation score of 63.13 ± 8.78. This was not statistically significant (t = 1.47, p = .150). Due to a lack of statistical significance in the control group as well (t = 0.57, p = .575), Hypothesis 1 was rejected (Table 2).

Table 1.

Homogeneity (N = 91).

| Category | Exp. group (n = 46) Mean ± SD/n (%) |

Cont. group (n = 45) Mean ± SD/n (%) |

X2/t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 23.52 ± 3.79 | 22.71 ± 1.84 | 1.30 | .199 |

| Gendera | 0.13 | .758 | ||

| Men | 5 (10.9) | 6 (13.3) | ||

| Women | 41 (89.1) | 39 (86.7) | ||

| Religion | 2.38 | .304 | ||

| Christianity | 8 (17.4) | 14 (31.1) | ||

| Catholic | 2 (4.3) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| None | 36 (78.3) | 29 (64.4) | ||

| Self-rated health | 4.03 | .133 | ||

| Good | 38 (82.6) | 31 (68.9) | ||

| Reasonable | 7 (15.2) | 14 (31.1) | ||

| Bad | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Reason for majoring in nursing | 3.60 | .609 | ||

| High graduate employment rates | 12 (26.1) | 12 (26.7) | ||

| Aptitude | 15 (32.6) | 8 (17.8) | ||

| Considering high school GPA | 5 (10.9) | 7 (15.6) | ||

| Family recommendation | 8 (17.4) | 8 (17.8) | ||

| Good impression of a nurse | 5 (10.9) | 9 (20.0) | ||

| Others | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| GPA | 0.96 | .810 | ||

| <3.0 | 4 (8.7) | 2 (4.4) | ||

| 3.0–3.5 | 14 (30.4) | 12 (26.7) | ||

| 3.5–4.0 | 18 (39.1) | 20 (44.4) | ||

| >4.0 | 10 (21.7) | 11 (24.4) | ||

| Residential status | 7.83 | .050 | ||

| With family member | 34 (73.9) | 42 (93.3) | ||

| With friends | 5 (10.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Alone | 6 (13.0) | 3 (6.7) | ||

| Other | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Satisfaction in major | ||||

| Very satisfying | 11 (23.9) | 4 (8.9) | 5.34 | .149 |

| Satisfying | 20 (43.5) | 27 (60.0) | ||

| Neutral | 12 (26.1) | 13 (28.9) | ||

| Not satisfying | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Not satisfying at all | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Communication skills | 61.52 ± 10.54 | 64.76 ± 6.83 | −1.74 | .087 |

| Communication attitudes | 88.00 ± 6.83 | 88.16 ± 8.76 | −0.10 | .925 |

| Team efficacy | 32.46 ± 6.38 | 35.49 ± 4.67 | −2.61 | .011⁎ |

Fisher's exact test.

p < .05.

Table 2.

Comparison of communication skills between two groups (N = 91).

| Group | Pre |

Post |

t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Exp. (n = 46) | 61.52 ± 10.54 | 63.13 ± 8.78 | 1.47 | .150 |

| Cont. (n = 45) | 64.76 ± 6.83 | 65.24 ± 7.44 | 0.57 | .575 |

-

Hypothesis 2: The nursing students who participated in the S-PBL will exhibit improved communication attitudes as compared to those who participated in the conventional clinical practice.

The experimental group's communication attitudes score was statistically significant (t = 2.41, p = .020). This was as it improved from a pre-simulation average score (SD) of 88.00 ± 6.83 to a post-simulation score of 91.07 ± 7.67. Conversely, the control group failed to demonstrate any statistical significance (t = 0.64, p = .526), thus supporting Hypothesis 2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of communication attitudes between two groups (N = 91).

| Group | Pre |

Post |

t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Exp. (n = 46) | 88.00 ± 6.83 | 91.07 ± 7.67 | 2.41 | .020⁎ |

| Cont. (n = 45) | 88.16 ± 8.76 | 89.09 ± 6.83 | 0.64 | .526 |

p < .05.

-

Hypothesis 3: The nursing students who participated in the S-PBL will exhibit improved team efficacy as compared to those who participated in the conventional clinical practice.

The team efficacy was tested after controlling for the effects of the differences in the pre-values. This was done by treating the pre-values as covariates because the prior measurements between the two groups lacked homogeneity. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (F = 3.30, p = .073). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is rejected (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of team efficacy between two groups (N = 91).

| Group | Pre |

Post |

Fa | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Exp. (n = 46) | 32.46 ± 6.38 | 34.93 ± 5.05 | 3.30 | .073 |

| Cont. (n = 45) | 35.49 ± 4.67 | 35.04 ± 4.78 |

Analyzed by ANCOVA with pretest value as a covariate.

4. Discussion

The majority of existing communication education is centered on special nursing situations, such as negotiating end of life care (Holms et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2014). Therefore, more education on common clinical cases is required to enhance the nursing core competencies. This includes the universal communication with a wide variety of patients (Gutiérrez-Puertas et al., 2020). Thus, the C-section maternity nursing S-PBL was developed based on Peplau's (1952) Interpersonal Relationship Model. This study designed and applied a team-based simulation learning method that offered an opportunity to perform communication frequently encountered by nurses in maternity nursing clinics. It is also applied to practical nursing care adapted to nursing situations.

This study found that the experimental group's communication attitudes increased significantly after participating in the S-PBL as compared to before their participation. This indicated that there was an improvement in the nursing students' communication competence. Given the considerable research, simulation and PBL specifically improved the professional communication competence between nursing students and patients (Webster, 2014; Yuan et al., 2019), and scenario-based simulation enhanced communication competence compared with traditional course (Hsu et al., 2015). In particular, communication was increased at integrating effective educational strategies such as S-PBL like the results of this study (Roh and Kim, 2015). This was consistent with a previous study's results (Jin et al., 2019) that conducted a communication training program on pharmaceutical college students. As such, the present study is believed to have improved students' communication attitudes. It achieved this by presenting cases commonly encountered in nursing education and clinical practice. It also achieved by designing scenarios, where effective communication skills could be applied (Keller, 2000). The communication attitudes are influenced by predisposing factors, such as previous learning experiences. In turn, the communication attitudes affect the effectiveness of communication education (Molinuevo et al., 2016). Hence, if future studies include an assessment and consideration of influencing factors associated with learner-specific characteristics, more effective communication education could be achieved.

In this study, the experimental group's communication skills increased after their S-PBL participation, however, the difference was not significant. This result differs from that of previous studies (Banerjee et al., 2017; Blake and Blake, 2019; Gutiérrez-Puertas et al., 2020), which proposed that simulation strengthened nursing students' communication skills. In caring for patients, their communication skills are considered a core competency to achieve optimal health outcomes (Molinuevo et al., 2016). In this study, after a 50-minute prebriefing, the C-section maternity nursing scenario took about 15 min to complete, immediately after small group activities, nursing students in each small group discussed and filled out the reflection journaling. The instructor also held a 50-minute debriefing for all students to reflect on the participation of the S-PBL. Given the past research, the running time of prebriefing, scenario display, and debriefing was appropriate for simulation-based learning (Hung et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019). In future studies, it is imperative that prebriefing and debriefing be used in S-PBL. This is to help prepare the nursing students in advance and to reduce unnecessary physiological tension and anxiety. It also helps to have an experienced nurse demonstrate nursing care, explain the effective communication methods, and provide adequate feedback. However, communication skills are taught and learned but are easily forgotten if not maintained through practice (Molinuevo et al., 2016). A previous study (Webster, 2014) demonstrated that students' communication skills were better during their second simulation participation. Given this, it was believed that in this study, the nursing students experienced simulated patient interactions for the first time. They also felt that performing the appropriate nursing care while communicating with patients may have affected their communication skills (Shearer, 2016; Webster, 2014). Conversely, the control group is believed to have been influenced by increasing their communication skills through the vicarious experience of monitoring the communication situation of nurses in conventional clinical practice. Furthermore, self-reported measures for assessment of simulation learning outcomes could pose limitations such as a lack of objectivity (Liaw et al., 2012). Therefore, it has been suggested that various objective assessment must be considered to support the validity for evaluation of learning outcomes from simulation.

The experimental group's team efficacy did not show statistically significant differences as compared to the control group. However, the mean value increased after S-PBL participation as compared to before it. This is while the mean value of the control group actually decreased. A previous study (Kim and Kim, 2021) has demonstrated that team-based education can enhance team efficacy. In particular, peer role-play in simulation-based education is to rehearse situations to improve learners' abilities to face with similar situations in clinical practice (Nestel et al., 2017). Such training can be especially valuable to nursing students who will become nurse professionals in the future. This is because the nursing duties involve much team cooperation. However, self-assessment has a potential danger that could lead towards overestimation of subjective confidence (Liaw et al., 2012). In addition, it has been suggested that various factors that impact team efficacy must also be considered for team-based simulations. These include individual characteristics, such as the grade and rapport among students (Kim and Kim, 2021).

Finally, the C-section maternity nursing S-PBL addresses the essential areas of nursing, including the nurses' communication with the patient. It was developed by analyzing the level of the learners who completed the human relations and communication courses in their first and second university years. It was also developed to promote their understanding of maternity nursing through the prerequisite course. The recent COVID-19 crisis has limited clinical nursing practice opportunities for nursing students. It thus makes it difficult for them to empirically learn how to respond appropriately to patients' nursing needs and questions (Blum et al., 2010; Kang, 2020; Lee et al., 2007). It has provided an alternative method of overcoming such limitations by implementing simulations that apply communication peer role-play based on Peplau's (1952) model. This is to obtain pre-training and nursing competencies for nursing practice. However, given that the participants were novice learners who experienced simulation and clinical practice training for the first time, this study should be viewed in the context of the possible effects of physiological tension and emotional conditions such as anxiety on the process of the delivery of educational materials (Shearer, 2016; Webster, 2014). In future nursing education and research, it is proposed that S-PBL be repeatedly implemented. It is also recommended that the effectiveness of nursing students' learning transfer be assessed over time. Furthermore, it is important to observe how communication skills, communication attitudes, and team efficacy change depending on learners' characteristics, which include grades. It is also important to provide practical communication education in stages, according to the learner's level.

4.1. Limitations

Given the inherent limitation of this cross-sectional study of having nursing students at a single university, caution must be taken when generalizing the results. Nursing students' self-assessment using the structured questionnaires poses limitations such as subjectivity. In particular, a simulated scenario was planned in a maternity nursing practicum. For future studies, it is crucial to compare the assessments of nursing students' learning transfer with multiple examples of maternity nursing. Furthermore, it is crucial to verify whether the communication competency acquired through the repeated and long-term educational effects are retained. Based on this study's findings, it is recommended that the learning objectives that students should accomplish when engaging in clinical practice in conjunction with various nursing practice courses be complemented. Ultimately, a further recommendation is to facilitate the nursing students' therapeutic communication and team cooperation as learning transfer.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis limits the opportunity for nursing students to receive direct nursing experience. As a result, there is a need for alternatives to complement the limitations in nursing practicum. There is also a need for systematic, integrated nursing simulations to facilitate learning about various nursing cases. Accordingly, based on Peplau's (1952) model, this study developed a C-section maternity nursing S-PBL scenario incorporating communication peer role-play. Especially, this study concluded that should pay special attention to professional communication between nursing students and patients and communication training using S-PBL may improve nursing students' communication. In the S-PBL, nursing students formed therapeutic relationships with patients. This allowed them to receive communication training and directly perform nursing in a more secure simulation environment than in a real-life clinical setting. Therefore, this study is significant in the sense that it recognized the nursing students' learning transfer in the context of communication between nurses and patients. It established an important foundation of clinical nursing education for preparing future professional nurses. Based on this study's findings, future research is particularly needed the standardized S-PBL to identify the long-term educational effects in various cases and settings.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant number: 2020R1G1A1010895).

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eulji University (No. EU21-015).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jeongim Lee: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft preparation, Supervision

Hae Kyoung Son: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bambini D., Washburn J., Perkins R. Outcomes of clinical simulation for novice nursing students: communication, confidence, clinical judgment. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2009;30:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000;9:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S.C., Manna R., Coyle N., Penn S., Gallegos T.E., Zaider T., Parker P.A. The implementation and evaluation of a communication skills training program for oncology nurses. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017;7(3):615–623. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows H. Southern Illinois University School of Medicine; Springfield, IL, USA: 1994. Problem-Based Learning Applied to Medical Education. [Google Scholar]

- Blake T., Blake T. Improving therapeutic communication in nursing through simulation exercise. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2019;14(4):260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bland A.J., Topping A., Wood B.A. Concept analysis of simulation as a learning strategy in the education of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today. 2011;31:664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum C.A., Borglund S., Parcells D. High fidelity nursing simulation: impact on student self-confidence and clinical competence. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2010;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S.H., Pagano M.P., O'Shea E.R., Connery C., Caron C. Development of the health communication assessment tool: enhancing relationships, empowerment, and power-sharing skills. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013;9(11):e543–e550. [Google Scholar]

- Cato M.L., Lasater K., Peeples A.I. Nursing students’ self-assessment of their simulation experiences. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2009;30(2):105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erci B., Sezgin S., Kaçmaz Z. The impact of therapeutic relationship on preoperative and postoperative patient anxiety. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;26(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J. In: Contemporary Nursing Knowledge. 2nd ed. DaCunha J., editor. F. A. Davis; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. Peplau’s theory of interpersonal relations; pp. 528–552. [Google Scholar]

- Gaba D.M. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl. 1):2–10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gully S.M., Incalcaterra K.A., Joshi A., Beaubien J.M. A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002;87(5):819–832. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Puertas L., Márquez-Hernández V.V., Gutiérrez-Puertas V., Granados-Gámez G., Aguilera-Manrique G. Educational interventions for nursing students to develop their communication skills with patients: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(7):2241–2262. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holms N., Miligan S., Kydd A. A study of the lived experiences of registered nurses who have provided end-of-life care within an intensive care unit. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2014;20(11):549–556. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.11.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L.L., Chang W.H., Hsieh S.I. The effects of scenario-based simulation course training on nurses’ communication competence and self-efficacy: a randomized controlled trial. J. Prof. Nurs. 2015;31:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.H., Tang F.I., Liu C.Y., Chen M.B., Liang T.H., Sheu S.J. Truth-telling to patients’ terminal illness: what makes oncology nurses act individually? Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014;18(5):492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C.C., Kao H.F.S., Liu H.C., Liang H.F., Chu T.P., Lee B.O. Effects of simulation-based learning on nursing students' perceived competence, self-efficacy, and learning satisfaction: a repeat measurement method. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;97:104725–104731. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.K., Park S.H., Kang J.E., Choi K.S., Kim H.A., Jeon M.S., Rhie S.J. The influence of a patient counseling training session on pharmacy students’ self-perceived communication skills, confidence levels, and attitudes about communication skills training. BMC Med. Educ. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1607-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. Simulated nursing practice education in the on-tact age: a mixed methods case study. J. Learner-Centered Curric. Instr. 2020;20(18):937–957. doi: 10.22251/jlcci.2020.20.18.937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.E., Kim J.Y. The impact of a team-based group readiness assurance test on nursing students’ problem solving, learning satisfaction, and team efficacy: a crossover study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;100:104819–104825. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J.M. How to Integrate Learner Motivation Planning Into Lesson Planning: The ARCS Model Approach. VII Semanario; Santiago, Cuba: 2000. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.J. Nursing students’ clinical judgment skills in simulation: using Tanner’s clinical judgment model. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2014;20(2):212–222. doi: 10.5977/jkasne.2014.20.2.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.R., Choi E.Y., Kang H.Y. Simulation module development and team competency evaluation. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2011;18(3):392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon E.M. Ewha Womans University; Seoul, South Korea: 2010. The Correlation Among Team Efficacy, Interpersonal Understanding, Proactivity in Problem Solving and Team Performance. Master’s Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Lasater K. Clinical judgement development: using simulation to create an assessment rubric. J. Nurs. Educ. 2007;46(11):496–503. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20071101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.O., Liang H.F., Chu T.P., Hung C.C. Effects of simulation-based learning on nursing student competences and clinical performance. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019;41:102646–102652. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.O., Eom M.R., Lee J.H. Use of simulation in nursing education. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2007;13(1):90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw S.Y., Scherpbier A., Rethans J.J., Klainin-Yobas P. Assessment for simulation learning outcomes: a comparison of knowledge and self-reported confidence with observed clinical performance. Nurse Educ. Today. 2012;32(6):e35–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley D.H., Brass D.J., Thomas J.B. Efficacy-performance spirals: a multilevel perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995;20:645–678. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi M., Zamanzadeh V., Valizadeh L., Khajehgoodari M. Assessment of nurse–patient communication and patient satisfaction from nursing care. Nurs. Open. 2019;6(3):1189–1196. doi: 10.1002/nop2.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCamant K.L. Humanistic nursing, interpersonal relations theory, and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2006;19:334–338. doi: 10.1177/0894318406292823. 10.1177/ 0894318406292823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L.C. University of Southern California; California, United States of America: 2003. The Relationship Between Efficacy, Teamwork, Effort and Patient Satisfaction. Doctoral Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo B., Aradilla-Herrero A., Nolla M., Clèries X. A comparison of medical students', residents' and tutors' attitudes towards communication skills learning. Educ. Health. 2016;29(2):132–135. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.188755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestel D., Kelly M., Jolly B., Watson M. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2017. Healthcare Simulation Education: Evidence, Theory & Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Oh K.O. Theory: theory of interpersonal relations: Hildegard E. Peplau. Korean J. Nurse Query. 2005;14(2):29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau H.E. Interpersonal Relations in Nursing. A Conceptual Frame of Reference for Psychodynamic Nursing. New York, United States of America; G.P. Putnam’s Sons: 1952. pp. 1–330. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau H.E. Interpersonal constructs for nursing practice. Nurse Educ. Today. 1988;7(5):201–208. doi: 10.1016/0260-6917(87)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau H.E., Ebrary I. Interpersonal Relations in Nursing: A Conceptual Frame of Reference for Psychodynamic Nursing. Springer; New York, United States of America: 1991. pp. 1–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rees C., Sheard C., Davies S. The development of a scale to measure medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills learning: the communication skills attitude scale (CSAS) Med. Educ. 2002;36:141–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh Y.S., Kim S.S. Integrating problem-based learning and simulation: effects on student motivation and life skills. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2015;33(7):278–284. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M.E. Dis-integration of communication in healthcare education: workplace learning challenge and opportunities. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017;100(11):2054–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth F.C., Constance J.H. Fundamentals of Nursing: Human Health and Function. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, United States of America: 2007. pp. 1–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J.N. Anxiety, nursing students, and simulation: state of the science. J. Nurse Educ. 2016;55(10):551–554. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20160914-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin I.S., Kim J.H. The effect of problem-based learning in nursing education: a meta-analysis. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2013;18(5):1103–1120. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H.K. Effects of S-PBL in maternity nursing clinical practicum on learning attitude, metacognition, and critical thinking in nursing students: a quasi-experimental design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:7866–7878. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travelbee J. Interpersonal Aspects of Nursing. 2nd ed. F.A. Davis Company; Philadelphia, United States of America: 1971. pp. 1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Webster D. Using standardized patients to teach therapeutic communication in psychiatric nursing. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2014;10(2):e81–e86. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.M., Hwang S.Y. Reliability and validity of the assessment tool for measuring communication skills in nursing simulation education. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2016;28(1):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Xiu W., Xuan-rui Z., Yan-xin Z., Jiao S. Effectiveness of problem-based learning on the professional communication competencies of nursing students and nurses: a systematic review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019;37:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]