Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Evidence regarding sex differences in clinical outcomes and treatment effect following intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is limited. Using the Antihypertensive Treatment in Intracerebral Hemorrhage-2 (ATACH-2) trial data, we explored whether sex disparities exist in outcomes and response to intensive blood pressure (BP)-lowering therapy.

Methods:

Eligible ICH subjects were randomly assigned to intensive (target systolic BP (SBP) 110–139 mmHg) or standard (140–179 mmHg) BP-lowering therapy within 4.5 h after onset. Relative risk (RR) of death or disability corresponding to the modified Rankin Scale 4–6 was calculated, and interaction between sex and treatment was explored.

Results:

In total, 380 women and 620 men were included. Women were older, more prescribed antihypertensive drugs before onset, and had more lobar ICH than men. Hematoma expansion was observed less in women. After multivariable adjustment, the RR of death or disability in women was 1.19 (1.02–1.37, p=0.023). The RR of death or disability between intensive vs. standard BP-lowering therapy was 0.91 (95% CI:0.74–1.13) in women vs. 1.13 (95% CI:0.92–1.39) in men (p for interaction=0.11), with inconclusive Gail-Simmon test (p=0.16).

Conclusions:

Women had a higher risk of death or disability following ICH. The benefit of intensive BP-lowering therapy in women is inconclusive, consistent with the overall results of ATACH-2.

Keywords: Intracranial Hemorrhage, Hypertensive, sex, blood pressure, Hypertension, Stroke

The uncertainty remains concerning the benefit of intensive blood pressure (BP)-lowering therapy in acute intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) following the recent two large clinical trials - the Second Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage Trial (INTERACT2) and Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage-II (ATACH-2).1,2

A systematic review reported that women had an unfavorable functional recovery, worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and a higher prevalence of post-stroke depression than men after stroke.3 In a recent pooled analysis of large stroke clinical trials, sex differences in mortality, disability, or stroke recurrence following ICH were not significant.4 Besides this study, few were designed to examine sex differences in ICH outcomes. Whether sex modifies the association between intensive BP-lowering therapy and clinical outcomes is also unknown.

In this prespecified analysis of ATACH-2, we aimed to explore whether sex is independently associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes after ICH and whether the response to BP-lowering therapy is different between sexes.

Methods

We used the open-to-public dataset of ATACH-2. In ATACH-2, subjects with spontaneous supratentorial ICH were randomly assigned to intensive (target SBP: 110–139 mm Hg) or standard (140–179 mm Hg) arm within 4.5 h of onset. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 4–6 was defined as an unfavorable clinical outcome (death or disability).2 To test for association of sex with outcomes, we calculated unadjusted and adjusted relative risk (RR) of death or disability and death in women versus men. Interaction between treatment and sex were also assessed. The ATACH-2 protocol was approved by the institutional review board or equivalent ethics committee at each participating site, and all participants or their legally authorized representative provided written informed consent. The dataset of ATACH-2 is currently open to the public and is available upon request to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). All data in this dataset are de-identified. Our research utilizing the publically available, anonymized dataset is an exemption from national ethical guidelines in Japan. Further details are provided in the online-only Data Supplement (https://www.ahajournals.org/journal/str).

Results

A total of 1000 subjects were enrolled in ATACH-2, and 38.0% were women. Demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by sex and treatment allocation are shown in Supplemental Table I & II. Compared with men, women were older and more prescribed antihypertensive drugs before the onset of ICH. Lobar ICH was more common in women. Hematoma expansion was observed less in women, and perihematomal edema expansion rate (PHER) was lower in women than in men.

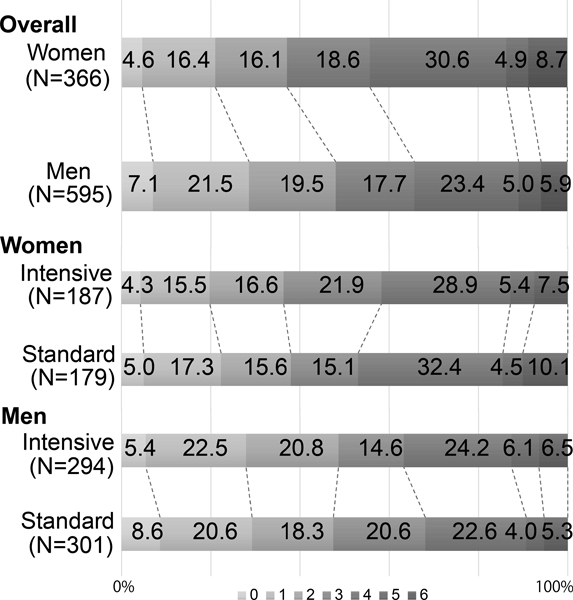

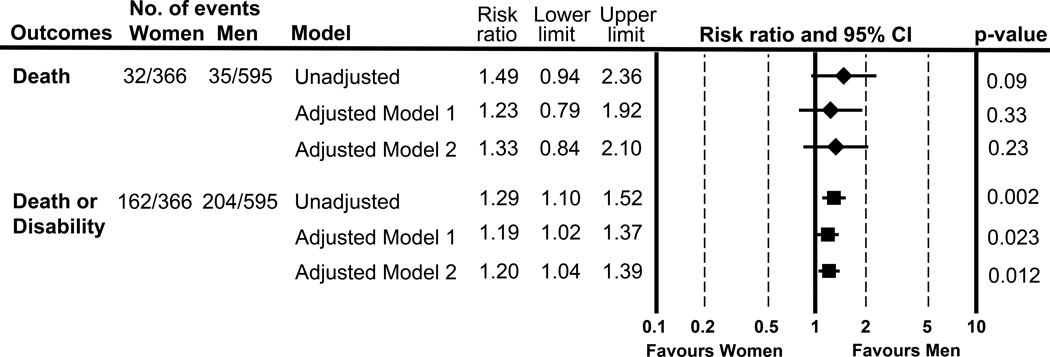

The proportion of death or disability, corresponding to mRS 4–6, was 44.3% in women vs. 34.3% in men (Figure1). The unadjusted and adjusted RR of (1) death and (2) death or disability are shown in Figure 2. With adjustment for prespecified covariates, the adjusted RR in women vs. men was (1) 1.23 (0.79–1.92) and (2) 1.19 (1.02–1.37,) (model 1), and (1) 1.33 (0.84–2.10) and (2) 1.20 (1.04–1.39) (model 2).

Figure 1.

Sex difference in the modified Rankin scale at 90 days.

Figure 2.

Sex difference in outcomes following intracerebral hemorrhage at 90 days

[Model 1]: Adjusted for Glasgow Coma Scale score, age, intraventricular hemorrhage, initial hematoma volume, and hematoma expansion. [Model 2]:additionally adjusted for initial edema volume and perihematomal edema expansion rate.

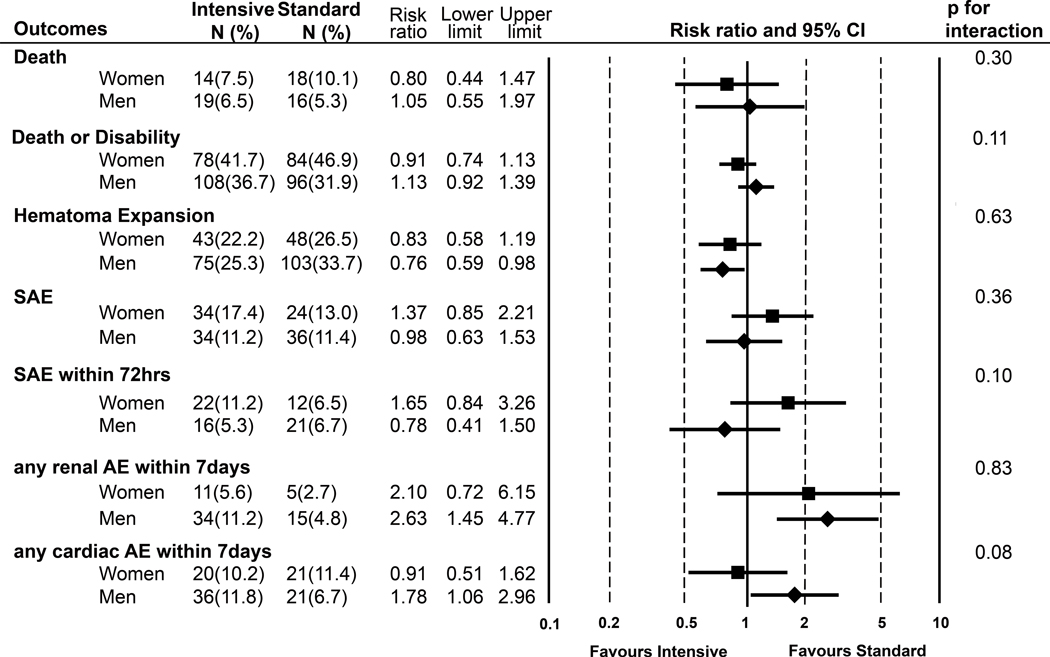

Statistically significant treatment-by-sex interaction was observed for death or disability (p for interaction=0.11), whereas the Gail-Simon test suggested no qualitative interaction (two-tailed p=0.16). SBP profiles of intensive vs. standard arm in both sexes were nearly identical (Supplemental Figure). The adjusted RR of death or disability in intensive vs. standard was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.74–1.13) among women and 1.13 (95% CI: 0.92–1.39) among men. Treatment-by-sex interaction were also observed in serious adverse events (SAEs) within 72 h (women: RR=1.65 (95% CI: 0.84–3.26) vs. men 0.78 (0.41–1.50); p for interaction=0.10) and any cardiac adverse events (AEs) within 7 days (women: 0.91 (0.51–1.62) vs. men: 1.78 (1.06–2.96) ; p for interaction=0.08)(Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sex difference in efficacy and safety of intensive SBP-lowering in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)

AE:adverse event, SAE: serious AE

Discussion

Here, we studied sex differences in clinical outcomes and the efficacy of intensive BP-lowering therapy following ICH.

The first significant finding was that women had a higher risk of death and disability than men at 90 days after ICH. After multivariable adjustment, women were independently associated with unfavorable outcomes.

In our analysis, hematoma expansion and PHER were treated as covariates since these are associated with poor outcomes.5–7 Seemingly paradoxical, though women had less hematoma expansion and lower PHER, their clinical outcomes were worse compared to men. Additional underlying mechanisms for sex differences in outcomes are suggested.

Stroke severity, poorer premorbid activity, and limited access to medical resources among women might contribute to the sex difference.8 In ATACH-2, however, the sex difference in the premorbid mRS, baseline NIHSS score, and time-delay in hospital arrival was not significant.

One plausible explanation for women’s poorer outcomes is a higher prevalence of post-stroke depression in women.3 Although specific depression scales were not measured, more women complained of anxiety/depression than men in the EQ-5D (Supplemental Table III). Previously, sex differences in the EQ-5D were not significant, except pain/discomfort.4 In our analysis, sex differences were significant in all dimensions, and overall, women reported worse HRQoL, though not translated into the mRS.

A higher incidence of frailty among women may attenuate the functional recovery. 9,10 Since frailty is associated with worse HRQoL,11 a higher rate of frailty among women was expected in our study. The prevalence of frailty is higher in the elderly; however, after adjustment for age, women were independently associated with unfavorable outcomes.

Due to the longer life expectancy in women, social isolation may play a key role in sex disparities following ICH. Recent large cohorts reported social isolation was independently associated with stroke morbidity and mortality.12 However, further studies are required to assess the inference.

Another important finding was a significant interaction between treatment and sex for death or disability. However, the relative treatment effects were comparable, and 95% CIs overlapped. Therefore we cannot conclude that intensive BP-lowering therapy in acute ICH is more beneficial for women. Note that we reported adjusted RRs, whereas the primary analysis reported unadjusted RRs.

Although a higher rate of renal AEs in the intensive arm was reported,2 sex did not modify the association between treatment and renal AEs. Overall, we could not find a significant additional risk of intensive SBP-lowering therapy in women and men.

The strengths of our study are a large number of study samples from diverse geographics, as well as the high-quality data with a limited number of missing. Our sensitivity analysis of missing data made no remarkable differences in the results/inference.

This study has some limitations. First, excluding some typical ICH patients with massive hematoma or infratentorial hemorrhage may limit generalizability. Second, we lacked data on long-term outcomes. Third, relatively small number of women included in this trial may raise the concern for the underrepresentation of women in the trial and therefore, the generalizability of the results. Forth, since our study is exploratory, caution in interpretation is advised on any statistically significant findings.

In conclusion, in this prespecified analysis of ATACH-2, women were independently associated with poor functional outcomes. Intensive SBP-lowering therapy did not reduce the poor outcomes in either women or men, which is consistent with the overall result of ATACH-2. Further studies focused on the reasons for the sex difference in outcomes may bring new insights for interventions targeting the unequal burden of ICH among women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Koko Asakura, Ph.D., for the statistical advice.

Sources of Funding

Supported by grants from NINDS (U01-NS062091, U01-NS061861, U01-NS059041), The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (JP17H04308), and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (20lk0201094h0002, 20lk0201109h0001 ).

Disclosures

KT reports honoraria (speaker fee) from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Yakuhin, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers-Squibb; outside the submitted work. MK reports personal fees from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and Ono, grants and personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Takeda, Astellas, Pfizer, and Shionogi, outside the submitted work. JN reports grants from Otsuka, Sanofi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Kyowa-Kirin, Takeda, Pfizer, Shionogi, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Sumitomo-Dainippon, Astellas, Novartis, Eisai, and Biogen, outside the submitted work. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: URL:https://www.clinicaltrials.gov. (NCT01176565)

Reference

- 1.Anderson CS, Heeley E, Huang Y, Wang J, Stapf C, Delcourt C, et al. Rapid blood-pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2355–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, Barsan WG, Hanley DF, Hsu CY, Martin RL, et al. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gall S, Phan H, Madsen TE, Reeves M, Rist P, Jimenez M, et al. Focused Update of Sex Differences in Patient Reported Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(3):531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carcel C, Wang X, Sandset EC, Delcourt C, Arima H, Lindley R, et al. Sex differences in treatment and outcome after stroke: Pooled analysis including 19,000 participants. Neurology. 2019;93(24):e2170–e2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SM, Broderick J, Hennerici M, Brun NC, Diringer MN, Mayer SA, et al. Hematoma growth is a determinant of mortality and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006;66(8):1175–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ironside N, Chen CJ, Ding D, Mayer SA, Connolly ES, Jr. Perihematomal Edema After Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50(6):1626–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leasure AC, Qureshi AI, Murthy SB, Kamel H, Goldstein JN, Walsh KB, et al. Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction and Perihematomal Edema Expansion in Deep Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2016–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordonnier C, Sprigg N, Sandset EC, Pavlovic A, Sunnerhagen KS, Caso V, et al. Stroke in women - from evidence to inequalities. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(9):521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Mazidi M, Zomer E, Ilomaki J, Zullo AR, et al. Global Incidence of Frailty and Prefrailty Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhamoon MS, Longstreth WT Jr., Bartz TM, Kaplan RC, Elkind MSV. Disability Trajectories Before and After Stroke and Myocardial Infarction: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(12):1439–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crocker TF, Brown L, Clegg A, Farley K, Franklin M, Simpkins S, et al. Quality of life is substantially worse for community-dwelling older people living with frailty: systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(8):2041–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Raback L, Virtanen M, Jokela M, Kivimaki M, Elovainio M. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart. 2018;104(18):1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.