Abstract

Background

Since the beginning of civilization, medicinal plants have been used in human healthcare systems. Studies have been conducted worldwide to evaluate their efficacy, and some of the results have triggered the development of plant-based medications. Rural women in Pakistan frequently experience gynaecological disorders due to malnutrition and heavy physical work during pregnancy. Due to the low economic status, the remoteness of the area, and the lack of modern health services, herbal therapy for gynaecological disorders is common among the indigenous tribes of the study area.

Methods

Field surveys were carried out from April 2018 to October 2020 to collect data regarding medicinal plants used for different gynaecological disorders. A semistructured questionnaire was used to collect ethnogynaecological data.

Results

In total, 67 medicinal plant species belonging to 38 families are being used to treat 26 different gynaecological problems. The herbaceous growth form and the Lamiaceae family were recorded with the maximum number of plant species (42 species and 7 species, respectively). Leaves are the most highly utilized plant part, with 16 species. In the case preparation method, decoction was the dominant method (25 species, 36.76%). The informants reported the maximum number of species for the treatment of irregular menstrual flow as 11 species (15.28%). The highest relative frequency of citation (RFC) value was obtained for Acacia modesta (0.37), and the use value (UV) for Tecomella undulata (0.85). The highest informants' consensus factor (ICF) value (1.0) was obtained for emmenagogue and tonic each after delivery. The highest consensus index (CI%) value was calculated for Acacia modesta (36.92%). The Lamiaceae had the highest family importance value (FIV) (98.46%).

Conclusion

This is the first ever quantitative study focusing mainly on ethnogynaecological study conducted in the tribal areas of North Waziristan which highlights the importance of traditional herbal remedies for their basic medical requirements. The results of this study would serve as a baseline for advanced phytochemical and pharmacological screening, as well as conservationists for further studies.

1. Introduction

Ethnogynaecology is a new branch of ethnobotany, which mainly deals with the use of therapeutic plants for curing gynaecological disorders such as menses problems, abortion, lactation, infertility, gonorrhea, leucorrhoea, and delivery disorders [1, 2]. It has been documented that sexual and other women's basic healthcare problems are reported to account for 18% of the total worldwide diseases [3]. Medicinal plants used to treat gynaecological disorders such as menstrual pain, abortion, leucorrhoea, pregnancy, infertility, lactation, and delivery problems have been documented in some areas of this region's ethnic groups [4]. The tribal communities have been preparing medication from the available medicinal plant species, which are widely used to cure common women's ailments. The tribal communities depend on therapeutic plants because of their efficacy, lack of basic medical care facilities, and ethnic preferences [5]. The medicinal plants used in traditional remedies are mostly collected from the wild. Tribal people have diverse knowledge of traditional medicine based on local plants for basic medical care [6]. In tribal communities, traditional healers possess a lot of information about medicinal plants. In these regions, medicinal plants are important for the indigenous people, providing access to basic healthcare [7]. The traditional medicinal system acts as the principal supplier of primary healthcare services in the tribal areas because of the lack of modern healthcare facilities, the remoteness of the region, and a strong cultural belief in the efficacy of folk medicines [8].

The use of medicinal plants in everyday life has a long history and still has immense importance in aboriginal civilization [9]. In remote areas, therapeutic plants still play an important role [10] and are still used as the basic healthcare system. According to the literature, more than 50,000 flowering taxa have been used for medical purposes all over the globe [11]. Pakistan has diverse flora comprised of about 6000 flowering plant species [12, 13] and about 600 plant species have been identified with medicinal values [14]. About 80% of the inhabitants of remote areas of Pakistan are still dependent on medicinal plants [15]. Plant-derived medicines account for about 25% of all medicines available in the modern pharmacies, with many more artificial compounds isolated from plants.

In Pakistan, rural women frequently experience gynaecological disorders due to malnutrition, poor living standards, and hard physical work during pregnancy. A local woman, who is locally called “Dayiah,” is found in each village and specializes in herbal therapy to relieve gynaecological disorders with local medicinal plants [16]. The highest use of the therapeutic plant in rural communities is due to the high price of allopathic medicine and its side effects [17]. A traditional way of life, as well as a lack of a suitable approach to modern health facilities, motivates rural women to consult with nearby midwives and indigenous healers [18].

There is very limited literature on ethnogynaecology [19], whereas many reports on ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal knowledge are available across the globe [18, 20]. Some ethnomedicinal surveys have been conducted to study the role of herbal therapy in women's medical and reproductive health disorders [20, 21]. Similarly, little literature is available about medicinal plants used by pastoral women for the healing of gynaecological problems. There is very little work carried out in Pakistan and in the whole world [22, 23]. Moreover, due to modernization and the lack of interest of younger generations in indigenous knowledge, which is declining speedily, ethnoecological information may vanish if not properly recorded [24]. In today's society, allopathic medicines, anti-inflammatory medicines, surgery, and nonsteroidal analgesics are commonly used to treat gynaecological disorders. These remedies are effective but usually have side effects, particularly when medicines are used for a long time. Moreover, some medicines used during the entire pregnancy period can harm the embryo [20].

This study aimed to record different types of plant species used against various gynaecological problems encountered by the female inhabitants of the tribal district of North Waziristan, Pakistan. The area is dominated by the Wazir and Dawar tribes, with low financial status, poor infrastructure, no modern medical facilities, and a lack of modern resources [14]. Many women and men in the region seek healing from a traditional therapist for a variety of problems related to the female reproductive organs. Such traditional knowledge has not been reported before from the study area as no ethnoecological documentation has been done earlier. Hence, this survey aims to report the ethnomedicinal knowledge of indigenous herbal remedies for the cure of gynaecological disorders and to preserve this precious but fast-vanishing indigenous knowledge of the tribal communities of the study area.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

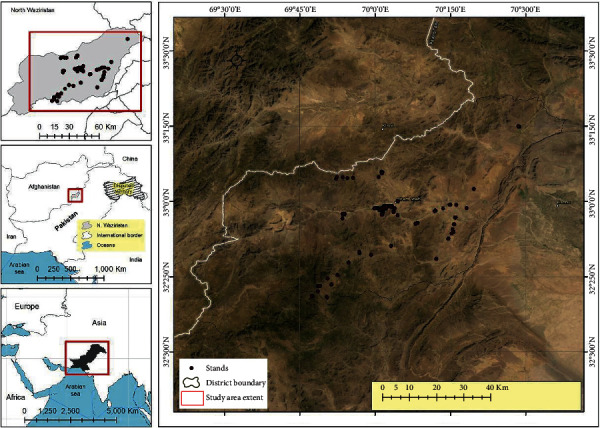

Tribal district North Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, is the hilly region that lies between 32°35′ and 33°20′ north latitudes and 69°25′ and 70°40′ east longitudes, with an altitude of 2143–7717 feet. North Waziristan falls under the Irano-Turanian Region [25]. The area is bounded by mountains that are connected with Koh-e-Sulaiman in the south and Koh-e-Sufaid in the north. North Waziristan is bounded on the south by the district of South Waziristan; on the north by Kurram Agency, Hangu district, and Afghanistan; on the east by the district of Bannu; and on the west also by Afghanistan (Figure 1). The area is fertile and is irrigated by 3 rivers, namely, the Tochi, Kurram, and Katu rivers. The annual rainfall is 45 cm. The North Waziristan area contains 4,707 square kilometers (1,817 sq mi). There are two major tribes in the study area, that is, Wazir and Dawar. Pushto is the major language. The study area is one of the major war-affected areas of Pakistan. The total population in the conflict-affected area of North Waziristan is approximately 840,000. The region has been targeted with shelling and air raids, and at least 456,000 people, including nearly 200,000 children (42%), fled ahead of or during the ground assaults to safer parts of Pakistan and neighbouring Afghanistan.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area (North Waziristan, KP, Pakistan). The black dots indicate the visited sites for the study.

2.2. Field Surveys and Medicinal Plants' Collection

The ethnogynaecological surveys were carried out in the tribal district (North Waziristan) from April 2018 to October 2020. Medicinal plants were collected during field visits [26, 27]. A collection number was given to each plant specimen with the help of tags. Plants were serially tagged and appropriately placed in the field presser. Snapshots of the collected plants were also captured [28, 29].

2.3. Questionnaires and Interviews

A semistructured questionnaire was used to collect the information regarding indigenous knowledge from the local informants and Hakeems of the study area [30–32]. Preference was given to elderly people and Hakeems. The collected specimens and photographs were further used in the interviews to recheck the information with other informants as well [28, 29]. A total of 130 local informants were interviewed, belonging to different age groups (35 years to 65 years), of which 105 were male and 25 were female, including housewives (daei/midwives and traditional healers) (Table 1) [33]. During the survey, local names, botanical names, folk uses, used parts, mode of preparation, mode of application (e.g., juice, paste, decoction, infusion, and powder), and growth/life form were documented by the local people of the study area. Through semistructured interviews [34, 35], knowledge about gender and age differences and occupation background and information about the herbal recipes for gynaecological disorders were documented [36].

Table 1.

Demographic information of the Informants.

| Variable | Categories | No. of informants N = 130 | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 105 | 80.77 |

| Female (Dayiahs/midwives) | 25 | 19.23 | |

|

| |||

| Informant category | Traditional healers | 90 | 69.23 |

| Indigenous people | 40 | 30.77 | |

|

| |||

| Occupation | Herbalists | 76 | 58.46 |

| Housewives | 25 | 19.23 | |

| Professional | 29 | 22.31 | |

|

| |||

| Age | 35–50 | 15 | 11.54 |

| 50–65 | 53 | 40.77 | |

| Above 65 | 62 | 47.69 | |

|

| |||

| Education level | Illiterate | 53 | 40.77 |

| Primary level | 34 | 26.15 | |

| Middle level | 15 | 11.54 | |

| Secondary level | 12 | 09.23 | |

| Undergraduate (Hakims) | 9 | 06.92 | |

| Graduate (Hakims) | 7 | 05.38 | |

2.4. Plant Identification and Preservation

The plant taxonomist Dr. Rahmatullah Qureshi identified the herbarium specimens and confirmed them with the help of available published literature [37]. These will be compared with identified specimens in the Herbarium of Pakistan Islamabad (ISL), Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad. Medicinal plant species were also photographed at the time of collection [38, 39]. The collected plants' specimens were dried, pressed, poisoned with 1% HgCl2 solution, and mounted on standard-sized herbarium sheets (11.5 × 17.5 inch). A voucher number was assigned and the voucher specimens were submitted to the herbarium of the Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan, for future references.

2.5. Quantitative Data Analysis

Indigenous knowledge is quantitatively analyzed using different quantitative indices [40–42] such as relative frequency of citation (RFC), used reports (UR), use value (UV), informant consensus factor (ICF), consensus index (CI%), fidelity level (FL%), and family importance value (FIV).

2.5.1. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

The RFC value for indigenous therapeutic plants is based on the number of informants for each plant species. A relative frequency of citation (RFC) is obtained by dividing the frequency of citation (FC) by the total number of informants in the survey (N). RFC was calculated by using the following formula [43, 44]:

| (1) |

where FC is frequency of citation and N is total number of informants taking part in the survey (N = 130).

2.5.2. Use Value (UV)

Use value (UV) of a species was determined by the following formula [45]:

| (2) |

where U is number of use reports documented by the informants for a given medicinal plant and n is total number of informants interviewed for a specific medicinal plant.

2.5.3. Consensus Index (CI%)

The percentage of local informants regarding their indigenous knowledge of therapeutic plants used to treat gynaecological problems was calculated by consensus index (CI%) [31]. The following formula was used:

| (3) |

where “n” is the number of informants citing the medicinal plant species and “N” is the total number of respondents for the species during the survey.

2.5.4. Fidelity Level (FL%)

The fidelity level (FL) is the percentage of informants who mention the utilization of particular medicinal plant species to cure specific ailments in the study area. The fidelity level (FL) is calculated by the following formula [46]:

| (4) |

where “Np” is the particular number of citations for a specific disease and “N” is the total number of respondents citing the plant species for any ailments.

2.5.5. Informant Consensus Factor (ICF)

Informant consensus factor (ICF) was used to determine the informants' agreement on the reported treatment for any diseases group or ailment category [47]. The ICF value ranges from 0 to 1. Thus, the following formula was used:

| (5) |

where Nur is the number of useful reports in any disease category and Nt is the number of plant species used.

2.5.6. Family Importance Value (FIV)

To determine the importance of a family, the family importance value (FIV) was applied [44] using the following formula:

| (6) |

where FC is number of informants mentioning the family and N is total number of informants taking part in the survey (N = 130).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Informants' Demography

This study was conducted in the tribal district of North Waziristan, Pakistan. Inhabitants use medicinal plants for the cure of different gynaecological disorders. Demographic knowledge was acquired from the gender, age, education level, and practice of the informants. A total of 130 informants were interviewed, including 80.77% male and 19.23% female (Dayiahs). All the informants spoke Pushto. The dominance of male informants in the study area was greater as compared to females. There were certain cultural barriers due to which female informants could not talk with male interviewers outside of their families, but the investigated female informants gave their assent. Many of them were over 65 years old (47.69%), followed by 50–65 years old (40.77%) and 35–50 years old (11.54%). Participants were 76 herbalists, 29 professionals, and 25 housewives (Table 1). The majority of herbal healers in this study were males. These results are similar to the previous literature [48]. Based on educational facilities, the indigenous knowledge and use of therapeutic plants for the treatment of gynaecological disorders were more prevalent in the illiterate people, that is, 40.77%, and the same traditional knowledge was declining in the graduate level (5.38%) of the study area. Based on age, it was observed that the indigenous knowledge and use of medicinal plants remedies for gynaecological disorders were more prevalent in the elders. The same results were documented by other authors from nearby areas and other countries [49, 50]. The inherited traditional knowledge of therapeutic plants is transferred orally and verbally from their ancestors and passed from generation to another [24]. Noticeably, information and knowledge related to the traditional medication of gynaecological disorders are vanishing due to the death of older females (Dayiahs) in the community. Hence, there is a dire need to conserve this indigenous knowledge from extinction [5].

3.2. Indigenous Medicinal Plants' Diversity

The study area has a wealthy floral diversity. For their basic medical care needs, tribal people have varying knowledge of traditional medicine associated with medicinal plants. All medicinal plant species along with their qualitative analysis (botanical names, family name, parts used, mode of preparation, mode of application, and disease treated) and quantitative analysis (RFC, FL, ICF, UV, and UR) of each medicinal plant species were calculated and are presented in Table 2. In this study, 67 medicinal plants belonging to 38 families were recorded as being used to treat gynaecological disorders by the indigenous people of tribal district of North Waziristan, Pakistan. Approximately, 84% of the rural population depends on herbal therapeutic plants [51]. In rural areas of Pakistan, approximately 75% of the inhabitants are still reliant on traditional knowledge for their basic healthcare system [52], because there is no modern healthcare facility provided to them. Thus, most of the inhabitants are dependent on herbal remedies in the study area. The most dominant family was the Lamiaceae with 7 species, followed by Asteraceae and Rosaceae with 4 species each (Table 2). The family Lamiaceae is predominant in the study area similar to the results reported in the previous work [53].

Table 2.

Medicinal plants with the quantitative analysis used for gynaecological disorders by the local communities of the tribal district of North Waziristan, Pakistan.

| Plants species | Family name | Vernacular name | Voucher no. | Habit | Parts used | Mode of preparation | Gynaecological use | Mode of application | FC | RFC | UR | UV | CI% | FL% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet | Malvaceae | Zergulai | SR-13340 | Shrub | Root | Powder + honey + milk | Leucorrhoea | The mixture of about one glass is taken once a day for seven days for the treatment of leucorrhoea. | 40 | 0.31 | 20 | 0.50 | 30.77 | 57.50 |

| Acacia modesta Wall. | Mimosaceae | Palusa | SR-13196 | Tree | Gum | Powder + butter oil + milk | Backache after delivery, aphrodisiac | The mixture of about one cup is taken twice a day for 3–5 days to treat backache after delivery and used as an aphrodisiac. | 48 | 0.37 | 37 | 0.77 | 36.92 | 100.00 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex Delile | Mimosaceae | Kekar | SR-13448 | Tree | Bark | Decoction | Gonorrhea | Decoction of one medium size cup is taken for three days to cure gonorrhea. | 27 | 0.21 | 14 | 0.52 | 20.77 | 62.96 |

| Achyranthes aspera L. | Amaranthaceae | Ghoshkai | SR-13311 | Herb | Leaves | Decoction | Labour pain | Decoction of leaves (half cup) is used to reduce excessive labour pain. | 23 | 0.18 | 12 | 0.52 | 17.69 | 69.57 |

| Adiantum capillus-veneris L. | Adiantaceae | Ebe betai | SR-13459 | Ferns | Leaves | Decoction | Abnormal stoppage of menstruation | Decoction of leaves of about one medium size cup for 4-5 days is taken and used as menstruation additive. | 24 | 0.18 | 16 | 0.67 | 18.46 | 50.00 |

| Ajuga bracteosa Wall. | Lamiaceae | Varekai boti | SR-13425 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Abnormal stoppage of menstruation | Decoction of aerial parts of about 1 cup for three days is taken and used as menstruation additive. | 20 | 0.15 | 13 | 0.65 | 15.38 | 55.00 |

| Ajuga parviflora Benth. | Lamiaceae | Shengulai | SR-13413 | Herb | Leaves, roots | Powder + milk | Amenorrhea | Powder (3 tablespoons) is given with one glass of warm milk for 6-7 days used to cure amenorrhea. | 14 | 0.11 | 8 | 0.57 | 10.77 | 50.00 |

| Allium sativum L. | Alliaceae | Yeza | SR-13462 | Herb | Bulb | Powder + curcumin powder | Easy delivery | Powder of 2 : 1 spoons is given to pregnant women with one glass of water used to stimulate uterine muscles for easy delivery. | 25 | 0.19 | 13 | 0.52 | 19.23 | 56.00 |

| Amaranthus spinosus L. | Amaranthaceae | Geta pakhe | SR-13326 | Herb | Roots | Decoction | Excessive menstruation | Decoction of roots (one cup) is taken for 3 days and used to reduce menstrual flow. | 21 | 0.16 | 11 | 0.52 | 16.15 | 57.14 |

| Amaranthus viridis L. | Amaranthaceae | Surme | SR-13341 | Herb | Leaves | Paste | Leucorrhoea | Leaves are cooked in oil and jaggery (gur) and the paste is taken for five days to treat leucorrhoea. | 22 | 0.17 | 13 | 0.59 | 16.92 | 59.09 |

| Androsace rotundifolia Hardw. | Primulaceae | Sergulai | SR-13424 | Herb | Leaves | Juice | Irregular menstrual flow | Fresh juice (2 spoons) for 5–7 days is taken to regularize menstrual flow. | 26 | 0.20 | 9 | 0.35 | 20.00 | 61.54 |

| Berberis lycium Royle | Berberidaceae | Therkha | SR-13444 | Shrub | Roots | Decoction | Gonorrhea | Decoction of roots (2 spoons) is taken for 7–10 days to cure gonorrhea. | 45 | 0.35 | 34 | 0.76 | 34.62 | 100.00 |

| Boerhavia diffusa L. | Nyctaginaceae | Pret boti | SR-13373 | Herb | Aerial parts | Decoction | Irregular menstrual flow | Decoction of aerial parts (1 spoonful) is given twice a day for seven days to regularize menstrual flow. | 39 | 0.30 | 28 | 0.72 | 30.00 | 61.54 |

| Bupleurum falcatum L. | Apiaceae | Pest boti | SR-13443 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Irregular menstrual flow | Decoction of the whole plant (3 spoons) is taken once a day for fifteen days to regulate the menses. | 28 | 0.22 | 13 | 0.46 | 21.54 | 64.29 |

| Calendula arvensis M.Bieb. | Asteraceae | Zer gulai | SR-13367 | Herb | Flower | Infusion | Painful menstruation | Infusion of flowers (10–15 ml) is taken twice a day to cure pain during menstruation. | 25 | 0.19 | 10 | 0.40 | 19.23 | 48.00 |

| Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. | Brassicaceae | Push boti | SR-13477 | Herb | Aerial parts | Decoction | Irregular menstrual flow | Decoction of aerial pats (2 spoonful) is taken thrice a day for 3–5 days to regularize menstrual flow. | 34 | 0.26 | 12 | 0.35 | 26.15 | 50.00 |

| Carum carvi L. | Apiaceae | Zera | SR-13467 | Herb | Seeds | Powder + butter oil | Expel impurities from the uterus | Powder of seeds (10 g) is mixed with butter oil, taken once a day for 5 days, and used to expel impurities from the uterus. | 44 | 0.34 | 31 | 0.70 | 33.85 | 97.73 |

| Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Chenopodiaceae | Khersapaka | SR-13531 | Herb | Leaves | Decoction | Painful menstruation, enhance milk flow | Leaves decoction (one cup) given twice a day for three days is recommended for painful menstruation. The same is given to nursing mothers to enhance the flow of breast milk. | 41 | 0.32 | 27 | 0.66 | 31.54 | 56.10 |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad | Cucurbitaceae | Maraginye | SR-13486 | Herb | Fruit | Juice | Easy delivery | Fresh juice of fruit (two spoons) is given to women during childbirth and is used for easy and smooth delivery. | 39 | 0.30 | 21 | 0.54 | 30.00 | 71.79 |

| Cnicus benedictus L. | Asteraceae | Pest azghi | SR-13473 | Herb | Aerial parts | Decoction + milk | Enhance milk flow | A decoction of aerial parts (one spoonful) is mixed with one glass of milk and given to nursing mothers to increase the flow of breast milk. | 27 | 0.21 | 14 | 0.52 | 20.77 | 77.78 |

| Cocculus pendulus (J.R. Forst. and G. Forst.) | Menispermaceae | Motiki boti | SR-13573 | Shrub | Roots | Decoction | Amenorrhea | Decoction of roots (15 ml) is given for 7–10 days continuously to treat amenorrhea. | 43 | 0.33 | 31 | 0.72 | 33.08 | 53.49 |

| Convolvulus arvensis L. | Convolvulaceae | Pervetia | SR-13215 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Irregular menstrual flow | Decoction of the plant (4 tea spoonful) is taken for 3-4 days to regulate menstrual flow. | 18 | 0.14 | 10 | 0.56 | 13.85 | 44.44 |

| Cydonia oblonga Mill. | Rosaceae | Bahi | SR-13520 | Shrub | Fruit, seeds | Jame, powder | Nausea and vomiting, leucorrhoea | Fruit jam (two teaspoonful) is given to pregnant women once in the early morning on an empty stomach for 3 days to treat nausea and vomiting. Seeds powder (1 teaspoonful) is mixed with honey and given once a day for 7 days to treat leucorrhoea. | 47 | 0.36 | 38 | 0.81 | 36.15 | 100.00 |

| Cyperus rotundus L. K | Cyperaceae | Delgai | SR-13296 | Sedge | Rhizome | Poultice | Enhance milk flow | A poultice of the rhizome is applied to the breast to increase the flow of breast milk. | 33 | 0.25 | 9 | 0.27 | 25.38 | 63.64 |

| Datura stramonium L. | Solanaceae | Berbaka | SR-13376 | Shrub | Leaves | Poultice | Breast swelling | A poultice of fresh leaves is topically applied on a nursing mother's breast to cure the inflammation of breasts. | 23 | 0.18 | 12 | 0.52 | 17.69 | 82.61 |

| Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq | Sapindaceae | Ghavajara | SR-13269 | Shrub | Leaves | Decoction | Excessive menstruation | Decoction of leaves (two spoons) is taken twice a day for 3 days to control excessive menstruation. | 43 | 0.33 | 27 | 0.63 | 33.08 | 79.07 |

| Eclipta prostrate (L.) | Asteraceae | Thorkvanai | SR-13359 | Herb | Whole plant | Herbal tea | Miscarriage | Herbal tea (1 tea spoonful) is given twice a day for 7 days to prevent miscarriage. | 23 | 0.18 | 12 | 0.52 | 17.69 | 73.91 |

| Equisetum arvense L. | Equisetaceae | Bandkai | SR-13216 | Ferns | Whole plant | Decoction | Gonorrhea | Decoction of plant (15–20 ml) is given once a day for 4-5 days and used to cure gonorrhea. | 27 | 0.21 | 13 | 0.48 | 20.77 | 77.78 |

| Erodium cicutarium L. | Geraniaceae | Not known | SR-13209 | Herb | Whole plant | Herbal tea + jaggery | Irregular menstrual flow, enhance milk flow | Herbal tea (two teaspoonful) with jaggery is given twice a day to regulate menstrual flow. The same is given to nursing mothers to increase the flow of breast milk. | 33 | 0.25 | 19 | 0.58 | 25.38 | 72.73 |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | Euphorbiaceae | Bayavenia | SR-13529 | Herb | Whole plant | Latex | Enhance milk flow | Latex (10 ml) is given once a day to the nursing mother to increase the flow of breast milk. | 31 | 0.24 | 16 | 0.52 | 23.85 | 70.97 |

| Fragaria nubicola (Hook.f.) Lindl. | Rosaceae | Jangli strawberi | SR-13429 | Herb | Fruit | Raw | Irregular menstrual flow | Fruits (5–10) are taken twice a day for three days to regulate menstrual flow. | 25 | 0.19 | 8 | 0.32 | 19.23 | 64.00 |

| Fritillaria imperialis L. | Liliaceae | Geger Gul | SR-13383 | Herb | Bulb | Powder + milk | Enhance milk flow | Bulb powder (one spoon) is given with one cup of milk to nursing mothers once a day for 7 days to increase the flow of breast milk. | 25 | 0.19 | 11 | 0.44 | 19.23 | 52.00 |

| Geranium wallichianum D. Don ex sweet | Geraniaceae | Varekai bote | SR-13389 | Herb | Roots | Powder + milk | Leucorrhoea, tonic after delivery | Roots powder (1 teaspoonful) mixed with milk and sugar is given twice a day for 3–5 days to cure leucorrhoea and is also used as tonic after delivery. | 41 | 0.32 | 23 | 0.56 | 31.54 | 78.05 |

| Gymnosporia nemorosa (Eckl. & Zeyh.) Szyszyl. | Celastraceae | Sagherzai | SR-13364 | Shrub | Fruit | Powder + butter oil | Labour pain | Fruit powder (10–12 gm) mixed with butter oil is given to pregnant women during childbirth to reduce excessive labor pain. | 29 | 0.22 | 11 | 0.38 | 22.31 | 72.41 |

| Justicia adhatoda L. K | Acanthaceae | Bikarh | SR-13233 | Shrub | Root, leaves | Paste + milk | Leucorrhoea | Roots paste (2 teaspoonful) mixed with one glass of milk is given twice a day for 15 days of and used to cure leucorrhoea. | 33 | 0.25 | 16 | 0.48 | 25.38 | 66.67 |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Brassicaceae | Bashke | SR-13320 | Herb | Seeds | Powder + milk | Abnormal stoppage of menstruation | Seeds powder (5-6 g) mixed with one glass of milk is given once a day for 3–5 days and used as a menstruation additive. | 20 | 0.15 | 9 | 0.45 | 15.38 | 65.00 |

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | Mimosaceae | Pest kekar | SR-13358 | Shrub | Seeds | Powder + honey | Menstrual cramps | Seeds powder (10 g) mixed with honey and taken twice a day for 4-5 days is recommended for menstrual cramps. | 23 | 0.18 | 11 | 0.48 | 17.69 | 60.87 |

| Melia azedarach L. | Meliaceae | Bakana | SR-13266 | Tree | Fruit gum | Powder + cow's milk | Emmenagogue | Fruits gum powder (4-5 g) mixed with cow's milk and given to women once a day for 2-3 days is recommended for emmenagogue. | 44 | 0.34 | 27 | 0.61 | 33.85 | 70.45 |

| Mentha spicata L. | Lamiaceae | Velanai | SR-13283 | Herb | Leaves | Juice | Easy delivery | Juice of leaves (one glass) is given to expectant mother to speed up child birth. | 20 | 0.15 | 13 | 0.65 | 15.38 | 65.00 |

| Mentha arvensis L. | Lamiaceae | Sarkori Velanai | SR-13284 | Herb | Whole plant | Powder | Antifertility | Powder of plant (2 spoons) mixed with one glass of water is given to women before the meeting and used for antifertility. | 21 | 0.16 | 11 | 0.52 | 16.15 | 85.71 |

| Mirabilis jalapa L. | Nyctaginaceae | Mazdergul | SR-13500 | Herb | Roots | Powder + milk | Sexual tonic | Roots powder (1 spoonful) mixed with one glass of milk is taken during nighttime daily for 7 days and used as a sexual tonic. | 36 | 0.28 | 16 | 0.44 | 27.69 | 80.56 |

| Nasturtium officinale R.Br. | Brassicaceae | Mangore | SR-13317 | Herb | Leaves, shoots | Juice | Produce temporary sterility | Juice of plant (one cup) is given to women daily for 3–5 days to produce temporary sterility. | 28 | 0.22 | 14 | 0.50 | 21.54 | 78.57 |

| Nepeta cataria L. | Lamiaceae | Khezbe | SR-13420 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Delayed menses | Decoction of plant (one cup) taken once a day for 5–7 days is recommended to delay menstruation. | 18 | 0.14 | 10 | 0.56 | 13.85 | 72.22 |

| Opuntia dillenii Haw. | Cactaceae | Sapre boti | SR-13168 | Shrub | Fruit | Baking + honey | Gonorrhea | Fruit juice is baked and mixed with honey and given twice a day for 10 days to cure gonorrhea. | 40 | 0.31 | 22 | 0.55 | 30.77 | 77.5 |

| Oxalis corniculata L. | Oxalidaceae | Threw boti | SR-13254 | Herb | Leaves | Chewing | Vomiting | The leaves are chewed to avoid vomiting during the early period of pregnancy. | 37 | 0.28 | 19 | 0.51 | 28.46 | 59.46 |

| Peganum harmala L. | Zygophyllaceae | Sponda | SR-13163 | Herb | Whole plant | Smoke | Antiseptic | The smoke of the plant passed on to the women after childbirth is used as an antiseptic. | 40 | 0.31 | 19 | 0.48 | 30.77 | 95.00 |

| Phyla nodiflora (L.) Greene. | Verbenaceae | Ebe betai | SR-13319 | Herb | Roots | Decoction + honey | Infertility | Decoction of root (10–12 ml) with honey (2 spoons) is given to women for promoting sexual desire. | 16 | 0.12 | 8 | 0.50 | 12.31 | 50.00 |

| Pistacia integerrima J. L. Stewart ex Brandis. | Anacardiaceae | Shene | SR-13464 | Tree | Gum | Powder + milk | Gonorrhea | Gum powder (8 g) mixed with milk and sugar is given once a day for 12 days to cure gonorrhea. | 43 | 0.33 | 21 | 0.49 | 33.08 | 90.70 |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Portulacaceae | Parkhorai | SR-13169 | Herb | leaves | Cooked | Excessive menstruation | Leaves are cooked in oil and black pepper and this paste is given for 3-4 days to control excessive menstruation. | 31 | 0.24 | 16 | 0.52 | 23.85 | 74.19 |

| Potentilla erecta (L.) Raeusch. | Rosaceae | Dhania ghonde | SR.13432 | Herb | Whole plant | Powder + curd | Excessive menstruation | Powder of plant (10 g) mixed with curd is taken daily for 3 days to control excessive menstruation. | 25 | 0.19 | 11 | 0.44 | 19.23 | 60.00 |

| Prunus domestica L. | Rosaceae | Manra | SR-13521 | Tree | Fruit | Raw | Vomiting | The unripe fruit is given to pregnant women to avoid vomiting during the early period of pregnancy. | 25 | 0.19 | 17 | 0.68 | 19.23 | 72.00 |

| Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | Arind | SR-13132 | Shrub | Seed | Powder | Abortion | Powder of seeds (15–20 g) is given with water to pregnant women for 3 days at the initial stage to induce abortion. | 37 | 0.28 | 18 | 0.49 | 28.46 | 72.97 |

| Solanum surattense Burm. f. | Solanaceae | Kurkundai | SR-13396 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction + jaggery | Conception | Decoction of the plant (one cup) mixed with jaggery is given for 5 days to promote the chance of pregnancy in females. | 43 | 0.33 | 27 | 0.63 | 33.08 | 90.70 |

| Tagetes erecta L. | Asteraceae | Zenda gula | SR-13260 | Herb | Roots | Decoction | Irregular menstruation | Decoction of roots (10–12 ml) is taken once a day for 3-4 days to regulate menstruation. | 25 | 0.19 | 13 | 0.52 | 19.23 | 56.00 |

| Tamarix aphylla (L.) H. Karst. | Tamaraceae | Ghaz | SR-13215 | Tree | Leaves | Smoke | Antiseptic | The smoke passed on to women after childbirth is used as an antiseptic. | 42 | 0.32 | 23 | 0.55 | 32.31 | 95.24 |

| Tecomella undulata (Roxb.) Seeman. | Bignoniaceae | Rawdana | SR-13378 | Shrub | Bark | Decoction + sugar | Lecucorroea | Decoction of the bark (one cup) mixed with sugar is given twice a day for 7 days to cure leucorrhoea. | 46 | 0.35 | 39 | 0.85 | 35.38 | 97.83 |

| Teucrium stocksianum Boiss. | Lamiaceae | Malgai | SR-13274 | Herb | Shoots | Powder + milk | Conception, miscarriage | Powder of shoot (8–10 g) mixed with milk is taken once a day for 5 days to increase chances of fertilization and to prevent miscarriage. | 20 | 0.15 | 11 | 0.55 | 15.38 | 90.00 |

| Thymus serpyllum L. | Lamiaceae | Pestekai | SR-13451 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction + sugar | Irregular menstruation | Decoction of the plant (one cup) mixed with sugar is given once a day for 3-4 days to regulate menses. | 15 | 0.12 | 8 | 0.53 | 11.54 | 60.oo |

| Trachyspermum ammi (L.) Sprague | Apiaceae | Sperkai | SR-13206 | Herb | Seeds | Powder | Irregular menstruation | Powder of the seeds (15–20 g) is taken with water twice a day for 3-4 days to regulate menstruation. | 41 | 0.32 | 21 | 0.51 | 31.54 | 95.12 |

| Trianthema portulacastrum L. | Azoiaceae | Mardor betai | SR-13339 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Abortion | Decoction of the plant (one glass) is given twice a day to pregnant women in the early period of pregnancy to induce abortion. | 45 | 0.35 | 27 | 0.60 | 34.62 | 77.78 |

| Tribulus terrestris L. | Zygophyllaceae | Markhiri | SR-13236 | Herb | Leaves | Decoction + sugar | Gonorrhea | Decoction of leaves (one cup) mixed with sugar is taken once a day for 5–7 days to cure gonorrhea. | 17 | 0.13 | 9 | 0.53 | 13.08 | 88.24 |

| Urtica dioica L. | Urticaceae | Sezankai | SR-13128 | Herb | Whole plant | Powder + cow's milk | Leucorrhoea | Powder of the plant (12–15 g) mixed with one glass of cow's milk is taken twice a day for 15 days to cure leucorrhoea. | 19 | 0.15 | 8 | 0.42 | 14.62 | 63.16 |

| Verbena officinalis L. | Verbenaceae | Bachawai | SR-13293 | Herb | Whole plant | Decoction | Miscarriage | Decoction of the plant (one cup) is given once a day for 5 days to prevent miscarriage. | 23 | 0.18 | 11 | 0.48 | 17.69 | 60.87 |

| Vitex negundo L. | Verbenaceae | Marwandai. | SR-13171 | Shrub | Shoots | Decoction + honey | Irregular menstruation | Decoction of the shoots (two teaspoonful) mixed with honey is taken once a day for 3-4 days to regulate menstrual flow. | 26 | 0.20 | 14 | 0.54 | 20.00 | 65.38 |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Solanaceae | Sre dane | SR-13230 | Shrub | Roots | Powder + butter oil | Sexual tonic | Powder of roots (6–8 g) mixed with butter oil is taken once a day during nighttime for 10 days to stimulate sexual desire. | 46 | 0.35 | 36 | 0.78 | 35.38 | 84.78 |

| Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. | Rhamnaceae | Bara | SR-13198 | Tree | Seeds | Paste | Leucorrhoea | The paste made from seeds is given twice a day for 15 days to cure leucorrhoea. | 21 | 0.16 | 11 | 0.52 | 16.15 | 76.19 |

| Ziziphus nummularia (Burm. f.) Wight and Arn. | Rhamnaceae | Karkana | SR-13179 | Shrub | Roots | Powder | Abortion | Powder of the roots (8–10 g) is given with water twice a day to pregnant women in the early stage of pregnancy to induce abortion. | 37 | 0.28 | 21 | 0.57 | 28.46 | 70.27 |

RFC: relative frequency of citation, FC: frequency of citation, UR: used reports, UV: use value, FL%: fidelity level, FIV: family importance value.

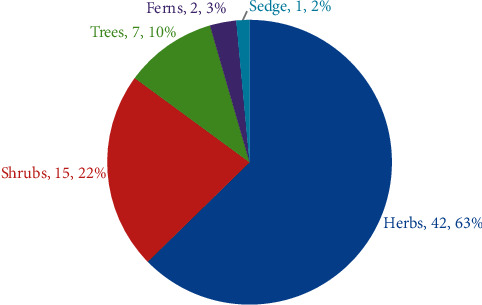

3.3. Life Form of the Ethnomedicinal Flora

In terms of life forms, the most dominant life form used in gynaecological remedies was herbs (42 species, 62.69%), followed by shrubs (15 species, 22.39%), trees (7 species, 10.45%), ferns (2 species, 2.99%), and sedge (1 species, 1.49%) (Figure 2). The frequent use of herbs in herbal remedies has also been documented in other areas of the globe [54, 55]. Herbs often have a high content of bioactive compounds [56], are easily accessible, and have profuse growth in wild varieties. Similar to other studies carried out by [57], easy accessibility of herbaceous plants or therapeutic plants, valuable healing action, and reasonable cost of the healthcare system are the major factors for the preference and advancement of herbal medication in the economically backward rural communities [58].

Figure 2.

The proportion of various plant life forms.

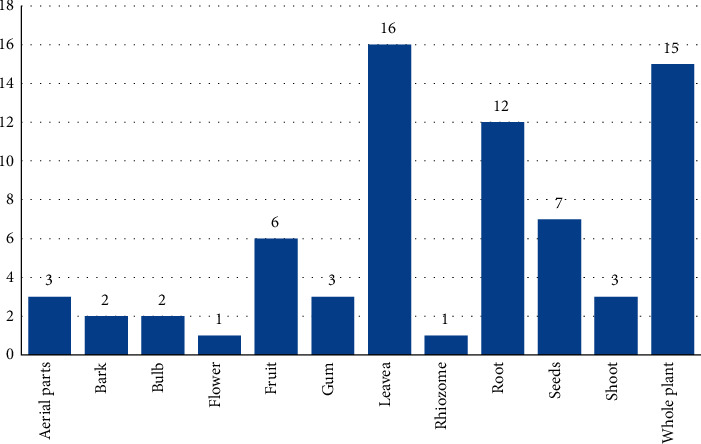

3.4. Plant Parts Used in Herbal Remedies

Various plant parts are regarded as useful in various ailments. The indigenous communities of North Waziristan, Pakistan, use approximately all parts of the medicinal plants as remedies for gynaecological problems. The most highly utilized parts for herbal remedies observed were leaves (16 species, 22.54%), followed by the whole plant (15 species, 21.13%), roots (12 species, 16.90%), seed (7 species, 9.86%), fruits (6 species, 8.45%), aerial parts, gum and shoots (3 species, 4.23% each), bark and bulb (2 species, 2.82% each), and flower and rhizome (1 species, 1.41% each) (Figure 3). The collection of leaves and medication preparation from leaves are so easy as compared to the other plant parts. For these purposes, leaves are commonly used in folk remedies [59]. The removal of leaves from the medicinal plants can cause less harm as compared to the removal of other parts of the plant [60]. The high use of leaves in herbal remedies preparation is also reported in other study areas [61–63].

Figure 3.

Plant parts are used in herbal remedies. The blue bar shows the “number of species.”

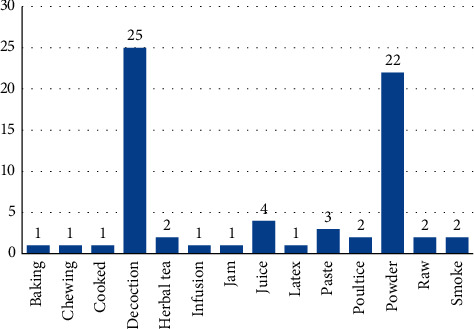

3.5. Preparation of Remedies

Medicinal plants were used by the indigenous people in diverse ways and in various recipes. A total of 14 modes of preparation were used in the indigenous communities. In the current study, decoction (25 species, 36.76%) is the dominant methodology used for the preparation of herbal remedies, followed by powder (22 species, 32.35%), juice (4 species, 5.88%), paste (3 species, 4.42%), herbal tea, poultice, raw, and smoke (2 species, 2.94% each) (Figure 4). Similarly, decoction and powder were reported as the most commonly used methods for preparing herbal remedies in other studies [64, 65].

Figure 4.

Mode of herbal drug preparation. The blue bar shows the “number of species.”

3.6. Mode of Administration

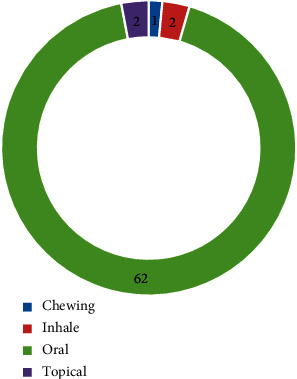

In this study, the dominant modes of administration/application were orally advised (62 species, 92.54%), followed by inhaling and topical (2 species, 92.54% each), and chewing (1 species, 1.49%) (Figure 5). The majority of oral administration was also reported in other study areas [66, 67].

Figure 5.

Mode of application/administration. The blue bar shows the “number of species.”

3.7. Indigenous Plants Used for the Treatment of Gynaecological Disorders

Tribal people have a wide range of knowledge about traditional medicine based on local plants for basic medical care [6]. During this ethnogynaecological study, 26 gynaecological disorders were documented, which were treated by using 67 medicinal plants (Table 3). The common gynaecological disorder in the study area was irregular menstrual flow, which was treated by using 11 plant species (15.28%), followed by leucorrhoea (8 species, 11.11%), enhanced milk flow and gonorrhea (6 species, 8.33% each), excessive menstruation (4 species, 5.56%), abnormal stoppage of menstruation, abortion, easy delivery, miscarriage, and vomiting (3 species, 4.17% each).

Table 3.

Gynaecological diseases treated by using indigenous plants.

| Sr. no. | Diseases | Number of species | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abnormal stoppage of menstruation | 3 | 4.17 |

| 2 | Abortion | 3 | 4.17 |

| 3 | Amenorrhea | 2 | 2.78 |

| 4 | Antifertility | 1 | 1.39 |

| 5 | Antiseptic | 2 | 2.78 |

| 6 | Backache after delivery | 1 | 1.39 |

| 7 | Breast swelling | 1 | 1.39 |

| 8 | Conception | 2 | 2.78 |

| 9 | Delayed menses | 1 | 1.39 |

| 10 | Easy delivery | 3 | 4.17 |

| 11 | Emmenagogue | 1 | 1.39 |

| 12 | Enhance milk flow | 6 | 8.33 |

| 13 | Excessive menstruation | 4 | 5.56 |

| 14 | Expel impurities from uterus | 1 | 1.39 |

| 15 | Gonorrhea | 6 | 8.33 |

| 16 | Infertility | 1 | 1.39 |

| 17 | Irregular menstrual flow | 11 | 15.28 |

| 18 | Labour pain | 2 | 2.78 |

| 19 | Leucorrhoea | 8 | 11.11 |

| 20 | Menstrual cramps | 1 | 1.39 |

| 21 | Miscarriage | 3 | 4.17 |

| 22 | Painful menstruation | 2 | 2.78 |

| 23 | Produce temporary sterility | 1 | 1.39 |

| 24 | Sexual tonic | 2 | 2.78 |

| 25 | Tonic after delivery | 1 | 1.39 |

| 26 | Vomiting | 3 | 4.17 |

3.8. Quantitative Analysis

The recorded data were analyzed through different statistical indices like RFC, UV, CI%, ICF, FL%, and FIV.

3.8.1. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

A relative frequency of citation was used to assess the most commonly used therapeutic plants [68] for gynaecological disorders. In this study, the RFC ranged from 0.11 to 0.37 (Table 2). Based on RFC values, the most valuable medicinal plant having a high degree of RFC was Acacia modesta (0.37), followed by Cydonia oblonga (0.36), Berberis lycium, Tecomella undulata, Trianthema portulacastrum, and Withania somnifera (0.35). The lowest RFC value was calculated for Ajuga parviflora (0.11). Those therapeutic plant species having the highest RFC value should be further analyzed pharmaceutically and phytochemically to identify their bioactive compounds for medicinal discovery [69, 70].

3.8.2. Use Value (UV)

According to [45], the use value indexation is a quantitative technique of ethnobotany that correlates the importance of plant species among aboriginal communities with regard to their uses. The use value in our documented data ranged from 0.27 to 0.85 and the use reports (URs) ranged from 9 to 39 (Table 2). The highest use value was reported for Tecomella undulata (0.85), followed by Cydonia oblonga (0.81), Withania somnifera (0.78), Acacia modesta (0.77), and Berberis lycium (0.76). The lowest use value (UV) was recorded for Cyperus rotundus (0.27). It was observed that the maximum use values were due to the higher number of use reports (URs) in the study area. The highest used values of documented therapeutic plants might indicate their indigenous professional expertise, which leads to a preference option for the disorder [71]. Medicinal plants with the lowest UV do not mean that they are not medicinally important, but it is shown that the traditional knowledge about these medicinal plants is limited [72]. Therapeutic plants for which the use value (UV) is high due to their frequent distribution in the research area and the inhabitants are well known for their medicinal value [35].

3.8.3. Consensus Index (CI%)

The percentage of informants having traditional indigenous knowledge of medicinal plant species used for illness control (in this study, gynaecological disorders) was determined using a consensus index (CI%) [73], which indicates the citation by percent of informants [74]. The consensus index (CI) value ranges from 10.77% to 36.92% (Table 2). The maximum CI value was obtained for Acacia modesta (36.92%), followed by Cydonia oblonga (36.15%), Tecomella undulata, and Withania somnifera (35.38%). The lowest consensus index (CI) value was calculated for Ajuga parviflora (10.77%). CI indicates an agreement on the fact that Acacia modesta and Cydonia oblonga are the most important and well-known therapeutic plants used for the treatment of gynaecological disorders in North Waziristan.

3.8.4. Fidelity Level (FL%)

Fidelity level (FL%) is used to determine the medicinal plant species that are most preferred by indigenous people for the cure of any specific ailment [46]. The therapeutic plants with the highest healing effects have the maximum fidelity level of 100%. The medicinal plant species that were mentioned by a single informant were not considered for the FL level study. In this study, FL ranged from 44.44% to 100% (Table 2). It is a fact that the higher the plant's utilization is, the higher the FL value will be. In this study, the highest FL was determined for Acacia modesta (backache after delivery), Berberis lycium (gonorrhea), and Cydonia oblonga (leucorrhoea) (100%), followed by Carum carvi (97.73%) for expelling impurities from the uterus and Tamarix aphylla (95.24%) for antiseptic, while the lowest FL was recorded for Convolvulus arvensis (44.44%) for irregular menstrual flow. The highest value of fidelity level (FL) determined the choice of informants to cure the specific disease [75].

3.8.5. Informant Consensus Factor (ICF)

The informant consensus factor (ICF) establishes the even sharing of informants' information regarding the medicinal plants, which validates that all the local people in the research area use plants for the treatment of the same ailment in same or different methods. In other words, the ICF value explains the cultural consistency in the use of a group of medicinal plants to treat a specific ailment [76]. To determine the informants' consensus factor (ICF), various diseases were grouped into 14 different disease categories based on taxa and use reports (Table 4). In this study, the ICF values ranged from 0.96 to 1.0. The highest ICF value was reported for emmenagogue and tonic after delivery (1.0), followed by antiseptic (0.99), and the lowest ICF value was reported for menstrual problems (0.96). Similar results were reported by [77] demonstrating that emmenagogue disorder has the highest ICF values.

Table 4.

Informant consensus factor (ICF) value for various diseases categories.

| Sr. no. | Use categories | Nur | Nt | Nur − Nt | Nur−1 | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amenorrhea | 57 | 2 | 55 | 56 | 0.98 |

| 2 | Antiseptic | 82 | 2 | 80 | 81 | 0.99 |

| 3 | Breast inflammation and lactation | 213 | 7 | 206 | 212 | 0.97 |

| 4 | Delivery problems | 84 | 3 | 81 | 83 | 0.98 |

| 5 | Emmenagogue | 44 | 1 | 43 | 43 | 1.00 |

| 6 | Gonorrhea | 199 | 6 | 193 | 198 | 0.97 |

| 7 | Induce abortion | 119 | 3 | 116 | 118 | 0.98 |

| 8 | Labour pain and backache | 100 | 3 | 97 | 99 | 0.98 |

| 9 | Leucorrhoea | 269 | 8 | 261 | 268 | 0.97 |

| 10 | Menstrual problems | 620 | 23 | 597 | 619 | 0.96 |

| 11 | Prevent miscarriage | 109 | 4 | 105 | 108 | 0.97 |

| 12 | Sexual problems | 147 | 5 | 142 | 146 | 0.97 |

| 13 | Tonic after delivery | 41 | 1 | 40 | 40 | 1.00 |

| 14 | Vomiting stoppage | 109 | 3 | 106 | 108 | 0.98 |

3.8.6. Family Importance Value (FIV)

The family importance value increases with the increase in the frequency of citations of all species. In this work, the most important family, based on the frequency of citations, was Lamiaceae with an FIV value of 98.46%, followed by Rosaceae (93.85%), Apiaceae (86.92%), Solanaceae (86.15%), Asteraceae (76.92%), and Mimosaceae (75.38%). Convolvulaceae has the lowest family importance value, with 13.85% (Table 5). Medicinally important plant species of the families Asteraceae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae, and Rosaceae are mentioned as important in various pharmacological works [78, 79]. The highest FIV value percentage reveals that the plants of a specific family are commonly used in treating various disorders, as reported by informants.

Table 5.

Family importance value (FIV) of medicinally important families.

| Sr. no. | Family name | No. of species | FC (family) | FIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acanthaceae | 1 | 33 | 25.38 |

| 2 | Adiantaceae | 1 | 24 | 18.46 |

| 3 | Alliaceae | 1 | 25 | 19.23 |

| 4 | Amaranthaceae | 3 | 66 | 50.77 |

| 5 | Anacardiaceae | 1 | 43 | 33.08 |

| 6 | Apiaceae | 3 | 113 | 86.92 |

| 7 | Asteraceae | 4 | 100 | 76.92 |

| 8 | Azoiaceae | 1 | 45 | 34.62 |

| 9 | Berberidaceae | 1 | 45 | 34.62 |

| 10 | Bignoniaceae | 1 | 46 | 35.38 |

| 11 | Brassicaceae | 3 | 82 | 63.08 |

| 12 | Cactaceae | 1 | 40 | 30.77 |

| 13 | Celastraceae | 1 | 29 | 22.31 |

| 14 | Chenopodiaceae | 1 | 41 | 31.54 |

| 15 | Convolvulaceae | 1 | 18 | 13.85 |

| 16 | Cucurbitaceae | 1 | 39 | 30.00 |

| 17 | Cyperaceae | 1 | 33 | 25.38 |

| 18 | Equisetaceae | 1 | 27 | 20.77 |

| 19 | Euphorbiaceae | 2 | 68 | 52.31 |

| 20 | Geraniaceae | 2 | 74 | 56.92 |

| 21 | Lamiaceae | 7 | 128 | 98.46 |

| 22 | Liliaceae | 1 | 25 | 19.23 |

| 23 | Malvaceae | 1 | 40 | 30.77 |

| 24 | Meliaceae | 1 | 44 | 33.85 |

| 25 | Menispermaceae | 1 | 43 | 33.08 |

| 26 | Mimosaceae | 3 | 98 | 75.38 |

| 27 | Nyctaginaceae | 2 | 39 | 30.00 |

| 28 | Oxalidaceae | 1 | 37 | 28.46 |

| 29 | Portulacaceae | 1 | 31 | 23.85 |

| 30 | Primulaceae | 1 | 26 | 20.00 |

| 31 | Rhamnaceae | 2 | 58 | 44.62 |

| 32 | Rosaceae | 4 | 122 | 93.85 |

| 33 | Sapindaceae | 1 | 43 | 33.08 |

| 34 | Solanaceae | 3 | 112 | 86.15 |

| 35 | Tamaraceae | 1 | 42 | 32.31 |

| 36 | Urticaceae | 1 | 19 | 14.62 |

| 37 | Verbenaceae | 3 | 65 | 50.00 |

| 38 | Zygophyllaceae | 2 | 57 | 43.85 |

3.9. Status of Medicinal Plants

According to local residents, the population of most medicinal plants has decreased over the last few decades. Threatened and endangered species of the study area are Berberis lycium, Fritillaria imperialis, Gymnosporia nemorosa, Pistacia integerrima, and Tecomella undulata. Excessive and injudicious use, overgrazing, improper harvesting practices such as digging out the entire plant, market pressure, and deforestation are also contributing factors. Medicinal plants are collected from the study area, transported to a small market by locals, and then exported to major cities. Locals also use shrubby species and trees as fuel sources, which have a negative impact on medicinal plant populations. Forests are necessary for the survival of several therapeutic plant species. As a result, the area's medicinally important plants are decreasing. Such flora need preservation through sustainable use, appropriate management, and conservation. A regional awareness campaign regarding the state of indigenous flora, sustainable plant harvesting, and the conservation of valuable therapeutic plants will lead to better outcomes. Local inhabitants, local stakeholders, and plant collectors should be aware of the conservation of plant resources in the region, and the indigenous people should be involved in conservation practices.

3.10. Novelty and Future Impacts

This study was compared with previously published literature of neighbouring areas and distant areas of utilization of medicinal plants for ethnogynaecological disorders [18, 80–86]. The comparative study between previously reported medicinal plants showed that some medicinal plants have the same or different medicinal uses, while some were documented for the first time and others were not previously documented. The following 9 species were reported for the first time to cure gynaecological diseases: Acacia modesta (aphrodisiac), Cnicus benedictus (enhance milk flow), Cocculus pendulus (amenorrhea), Cydonia oblonga (leucorrhoea), Cyperus rotundus (enhance milk flow), Peganum harmala (antiseptic), Prunus domestica (vomiting), Tamarix aphylla (antiseptic), and Tecomella undulata (leucorrhoea) (Table 2). Many ethnomedicinal studies have similar medicinal uses of therapeutic plants for the treatment of various ailments all over the globe. This study adds some new therapeutic plant uses, which may provide baseline data for phytochemical and pharmacological screening for the detection of new drugs in future studies. The discovery of drugs from therapeutic plants links an interdisciplinary approach to joining ethnomedicinal, pharmacological, botanical, and natural methods. However, any medicinal plants in this study area are not subjected to detailed pharmacological screenings.

4. Conclusion

This study focuses on pastoral women's health and healing. In rural areas, modern health facilities are insufficient or not available. Rural people (midwives, traditional healers) have indigenous knowledge of herbal remedies for treating gynaecological disorders. In the research area, 67 therapeutic plants are used to treat 26 different types of gynaecological disorders. Leaves are the dominant part used in the preparation of herbal remedies for gynaecological disorders. Menstrual problems were the most prevalent ailment category treated using 26 therapeutic plants in the study area. Decoction and powder were reported as the most commonly used methods for preparing herbal remedies, which clearly shows the consistency with other studies as well [53, 54]. The highest use value was reported for Tecomella undulata (0.85), followed by Cydonia oblonga (0.81) and Withania somnifera (0.78). It was observed that the medicinal plants having maximum UV were due to their higher number of use reports (URs) in the study area. The literature reveals that the therapeutic plants with higher UV are because of their frequent distribution in the research area and the inhabitants are well known for their medicinal value [62], which leads them to be the preferred option for the particular ailment [59]. The cultural consistency in the use of a group of medicinal plants to treat a specific ailment group was explained using ICF [47], through which the consistency of our results was found in accordance with Sadeghi et al. [20]; they reported that emmenagogue disorder has the highest ICF values. Some medicinal plants, like Berberis lycium, Fritillaria imperialis, Gymnosporia nemorosa, Pistacia integerrima, and Tecomella undulata are under extreme pressure as a result of the indiscriminate collection by locals. We believe that forest protection and floral habitat conservation are critical. For this, the government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) must design appropriate programmes with the participation of local people who must be educated about the need to maintain precious forest resources and participate in forestation for future generations. This survey provides a baseline for future clinical and pharmacological studies in the field of gynecology. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the medicinal uses of the reported plants [48]. Detailed clinical and pharmacological trials are needed to find out the bioactive components for the treatment of the gynaecological disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the local community members of the study area for sharing their valuable information. The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project no. RSP-2021/190, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability

The figures and tables supporting the results of this study are included within the article, and the original datasets are available from the first author or the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

References

- 1.Lawal I. O., Amao A. O., Lawal K. O., Alamu O. T., Sowunmi I. L. Phytotherapy approach for the treatment of gynaecological disorder among women in Ido local government area of ibadan, oyo state, Nigeria. Journal of Advanced Scientific Research . 2013;4(03):41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman A. H. M. M., Jahan-E-Gulsan S. M., Naderuzzaman A. T. M. Ethno-Gynecological disorders of folk medicinal plants used by santhals of dinajpur district, Bangladesh. Frontiers of Biological and Life Sciences . 2014;2(3):p. 62. doi: 10.12966/fbls.09.03.2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaingu C. K., Oduma J. A., Kanui T. I. Practices of traditional birth attendants in Machakos District, Kenya. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2011;137(1):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel P. K., Patel M. K. Ethnogynaecological uses of plants from Gujarat, India. Bangladesh Journal of Plant Taxonomy . 2012;19(1):93–94. doi: 10.3329/bjpt.v19i1.10947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed Khattak N., Nouroz F., Ur Rahman I., Noreen S. Ethno veterinary uses of medicinal plants of district Karak, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;171:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rekka R., Murugesh S., Prabakaran R., Tiruchengode N. D. Plants used by malayali tribes in ethnogynaecological disorders in yercaud hills, southern eastern ghats, salem district, Tamil nadu. Reporter . 2013;3:190–192. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiringe J. W. Ecological and anthropological threats to ethno-medicinal plant resources and their utilization in Maasai communal ranches in the Amboseli region of Kenya. Ethnobotany Research and Applications . 2005;3:231–242. doi: 10.17348/era.3.0.231-242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattarai S., Chaudhary R. P., Quave C. L., Taylor R. S. L. The use of medicinal plants in the trans-himalayan arid zone of Mustang district, Nepal. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2010;6(1):14–11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman I. U., Afzal A., Iqbal Z., et al. Historical perspectives of ethnobotany. Clinics in Dermatology . 2019;37(4):382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi R. A., Ghufran M. A. Medicinal value of some important roses and allied species of northeren area of Pakistan. Pakistan Rose Annu . 2005:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schippmann U., Leaman D. J., Cunningham A. B. Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture . Québec, Canada: Forestry and Fisheries; 2002. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues; pp. 675–706. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amjad M. S., Arshad M., Saboor A., Page S., Chaudhari S. K. Ethnobotanical profiling of the medicinal flora of Kotli, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan: empirical reflections on multinomial logit specifications. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine . 2017;10(5):503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbasi A. M., Khan M. A., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Jahan S., Sultana S. Ethnopharmacological application of medicinal plants to cure skin diseases and in folk cosmetics among the tribal communities of North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2010;128(2):322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murad W., Azizullah A., Adnan M., et al. Ethnobotanical assessment of plant resources of banda daud shah, district karak, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2013;9(1):77–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad Jan H., Wali S., Ahmad L., Jan S., Ahmad N., Ullah N. Ethnomedicinal survey of medicinal plants of Chinglai valley, Buner district, Pakistan. European Journal of Integrative Medicine . 2017;13:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat J. A., Kumar M., Bussmann R. W. Ecological status and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in kedarnath wildlife sanctuary of garhwal himalaya, India. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2013;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marwat S. K., Rehman F. U. Medicinal folk recipes used as traditional phytotherapies in district Dera Ismail Khan, KPK, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2011;43(3):1453–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qureshi R. A., Ghufran M. A., Gilani S. A., Zaheer Y., Ghulam A., Aniqa B. Indigenous medicinal plants used by local women in southern Himalayan regions of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2009;41(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahu P. K. Plants used by Gond and Baiga women in ethnogynaecological disorders in Achanakmar wild life sanctuary, Bilaspur. International Journal of Pharmacy and Life Sciences . 2011;2:559–561. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadeghi Z., Mahmood A. Ethno-gynecological knowledge of medicinal plants used by Baluch tribes, southeast of Baluchistan, Iran. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia . 2014;24(6):706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2014.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhingra R., Kumar A., Kour M. Knowledge and practices related to menstruation among tribal (Gujjar) adolescent girls. Studies on Ethno-Medicine . 2009;3(1):43–48. doi: 10.1080/09735070.2009.11886336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui M. B., Alam M. M., Hussain W., Sharma G. K. Ethnobotanical study of plants used for terminating pregnancy. Fitoterapia . 1998;59:250–252. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dash K., Satapathy C. S. Ethno medicinal uses of plants related to gynecological problem among the Mundas of Jajpur district of Odisha. Journal of Medicinal Plants . 2016;4(6):248–251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan M. P. Z., Ahmad M. Traditional preference of Wild Edible Fruits (WEFs) for digestive disorders (DDs) among the indigenous communities of Swat Valley-Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;174:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali S. I. Significance of flora with special reference to Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2008;40(3):967–971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ijaz F., Iqbal Z., Alam J., et al. Ethno medicinal study upon folk recipes against various human diseases in Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, Pakistan. World Journal of Zoology . 2015;10(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ijaz F. Biodiversity and Traditional Uses of Plants of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, M.Phil Dissertation . Mansehra, Pakistan: Hazara University Manehra; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman I. U., Afzal A., Iqbal Z., et al. Herbal teas and drinks: folk medicine of the manoor valley, lesser himalaya, Pakistan. Plants . 2019;8(12):p. 581. doi: 10.3390/plants8120581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ijaz F., Iqbal Z., Rahman I. U., et al. Investigation of traditional medicinal floral knowledge of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, KP, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;179:208–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman I. U., Afzal A., Iqbal Z., Ijaz F., Ali N., Bussmann R. W. Traditional and ethnomedicinal dermatology practices in Pakistan. Clinics in Dermatology . May 2018;36(3):310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman I. U., Ijaz F., Afzal A., Iqbal Z., Ali N., Khan S. M. Contributions to the phytotherapies of digestive disorders: traditional knowledge and cultural drivers of Manoor Valley, Northern Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;192:30–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ijaz F., Rahman I. ., Iqbal Z., Alam J., Ali N., Mulk Khan S. Ethno-ecology of the healing forests of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, Pakistan: an economic and medicinal appraisal. In: Ozturk M., Hakeem K. R., editors. Plant and Human Health . 1st. Berlin, Germany: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018. pp. 675–706. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motti R., Motti P. An ethnobotanical survey of useful plants in the agro Nocerino Sarnese (Campania, southern Italy) Human Ecology . 2017;45(6):865–878. doi: 10.1007/s10745-017-9946-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahman I. U., Hart R., Afzal A., et al. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research . 2019;17(2):2765–2777. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1702_27652777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman I. U., Ijaz F., Iqbal Z., et al. A novel survey of the ethno medicinal knowledge of dental problems in Manoor Valley (Northern Himalaya), Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;194:877–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin G. J. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual . London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nasir Y. J., Rafiq R. A., Roberts T. J. Wild Flowers of Pakistan . Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman I. U. Ecophysiological Plasticity and Ethnobotanical Studies in Manoor Area, Kaghan Valley, Pakistan, PhD Dissertation . Mansehra, Pakistan: Hazara University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman I. U., Bussmann R. W., Afzal A., Iqbal Z., Ali N., Ijaz F. Folk formulations of Asteraceae species as remedy for different ailments in lesser himalayas, Pakistan. In: Abbasi A. M., Bussmann R. W., editors. Ethnobiology of Mountain Communities in Asia . Berlin, Germany: Springer International Publishing AG; 2020. pp. 295–325. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan K., Rahman I. U., Calixto E. S., Ali N., Ijaz F. Ethnoveterinary therapeutic practices and conservation status of the medicinal flora of chamla valley, khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Frontiers in Veterinary Science . 2019;6(APR):p. 122. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehman S., Iqbal Z., Qureshi R., et al. Ethnoveterinary practices of medicinal plants among tribes of tribal District North waziristan, khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Frontiers in Veterinary Science . 2022;9(MAR):p. 182. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.815294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majid A., Ahmad H., Saqib Z., et al. Exploring threatened traditional knowledge; ethnomedicinal studies of rare endemic flora from Lesser Himalayan region of Pakistan. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia . 2019;29(6):785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2019.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butt M. A., Ahmad M., Fatima A., et al. Ethnomedicinal uses of plants for the treatment of snake and scorpion bite in Northern Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;168:164–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malik K., Ahmad M., Zafar M., et al. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases in northern Pakistan. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2019;19(1):210–238. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2605-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips O. L., Hall P., Gentry A. H., Sawyer S. A., Vasquez R. Dynamics and species richness of tropical rain forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 1994;91(7):2805–2809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman J., Yaniv Z., Dafni A., Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 1986;16(2–3):275–287. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuasha N., Petros B., Asfaw Z. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers to treat malignancies and other human ailments in Dalle District, Sidama Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . Feb. 2018;14(1):p. 15. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amujoyegbe O. O., Idu M., Agbedahunsi J. M., Erhabor J. O. Ethnomedicinal survey of medicinal plants used in the management of sickle cell disorder in Southern Nigeria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . Jun. 2016;185:347–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbasi A. M., Khan M. A., Khan N., Shah M. H. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinally important wild edible fruits species used by tribal communities of Lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;148(2):528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alam N., Shinwari Z. K., Ilyas M., Ullah Z. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants of Chagharzai valley, District Buner, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2011;43(2):773–780. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad M., Khan M. P. Z., Mukhtar A., Zafar M., Sultana S., Jahan S. Ethnopharmacological survey on medicinal plants used in herbal drinks among the traditional communities of Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;184:154–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ullah M., Khan M. U., Mahmood A., et al. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Wana district south Waziristan agency, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;150(3):918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aziz M. A., Khan A. H., Adnan M., Ullah H. Traditional uses of medicinal plants used by Indigenous communities for veterinary practices at Bajaur Agency, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2018;14(1):p. 11. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muthu C., Ayyanar M., Raja N., Ignacimuthu S. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2006;2(1):43–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kala C. P. Ethnomedicinal botany of the apatani in the eastern himalayan region of India. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2005;1(1):11–18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lulekal E., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Van Damme P. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used for human ailments in ankober district, north shewa zone, amhara region, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2013;9(1):p. 63. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uniyal S. K., Singh K. N., Jamwal P., Lal B. Traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, Western Himalaya. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2006;2(1):p. 14. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Konno B. Integration of Traditional Medicine with Modern Medicine . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: EHNRI; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Telefo P. B., Lienou L. L., Yemele M. D., et al. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of female infertility in Baham, Cameroon. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2011;136(1):178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kadir M. F., Bin Sayeed M. S., Mia M. M. K. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Bangladesh for gastrointestinal disorders. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . May 2013;147(1):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akhtar N., Rashid A., Murad W., Bergmeier E. Diversity and use of ethno-medicinal plants in the region of Swat, North Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2013;9(1):p. 25. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hachi M., Hachi T., Belahbib N., Dahmani J., Zidane L. Contribution a l’etude floristique et ethnobotanique de la flore medicinale utilisee au niveau de la ville de Khenifra (Maroc)/(contribution to the study and floristic ethnobotany flora medicinal use at the city of Khenifra (Morocco)) International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies . 2015;11(3):p. 754. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah S. A., Shah N. A., Ullah S., et al. Documenting the indigenous knowledge on medicinal flora from communities residing near Swat River (Suvastu) and in high mountainous areas in Swat-Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2016;182:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gürdal B., Kültür Ş. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Marmaris (Muğla, Turkey) Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;146(1):113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bano A., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Sultana S., Rashid S., Khan M. A. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of the most commonly used plants from deosai plateau, western himalayas, gilgit baltistan, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;155(2):1046–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benarba B., Meddah B., Tir Touil A. Response of bone resorption markers to Aristolochia longa intake by Algerian breast cancer postmenopausal women. Advances in Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2014;2014:4. doi: 10.1155/2014/820589.820589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chermat S., Gharzouli R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the north east of Algeria-an empirical knowledge in djebel zdimm (setif) Journal of Material Science & Engineering . 2015;5:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mrabti H. N., Jaradat N., Kachmar M. R., et al. Integrative herbal treatments of diabetes in Beni Mellal region of Morocco. Journal of Integrative Medicine . 2019;17(2):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vitalini S., Iriti M., Puricelli C., Ciuchi D., Segale A., Fico G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—an alpine ethnobotanical study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;145(2):517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mukherjee P. K., Nema N. K., Venkatesh P., Debnath P. K. Changing scenario for promotion and development of Ayurveda--way forward. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2012;143(2):424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ullah S., Rashid Khan M., Ali Shah N., Afzal Shah S., Majid M., Asad Farooq M. Ethnomedicinal plant use value in the lakki marwat district of Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;158:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahmood A., Mahmood A., Malik R. N., Shinwari Z. K. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants from Gujranwala district, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2013;148(2):714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belhaj S., Chaachouay N., Zidane L. Ethnobotanical and toxicology study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes in the High Atlas Central of Morocco. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmacognosy Research . 2021;9(5):619–662. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sreekeesoon D. P., Mahomoodally M. F. Ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants and animals used in the treatment and management of pain in Mauritius. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;157:181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bisi-Johnson M. A., Obi C. L., Kambizi L., Nkomo M. A survey of indigenous herbal diarrhoeal remedies of OR Tambo district, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. African Journal of Biotechnology . 2010;9(8):1245–1254. doi: 10.5897/ajb09.1475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Social Science & Medicine . 1998;47(11):1859–1871. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sadeghi Z., Kuhestani K., Abdollahi V., Mahmood A. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants of Saravan region, Baluchistan, Iran. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;153(1):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tareen N. M., Rehman M. A., Shinwari Z. K., Bibi T. Ethnomedicinal utilization of wild edible vegetables in district Harnai of Balochistan Province-Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2016;48(3):1159–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shad A. A., Shah H. U., Bakht J. Ethnobotanical assessment and nutritive potential of wild food plants. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences . 2013;23(1):92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aziz M. A., Khan A. H., Ullah H., Adnan M., Hashem A., Abd_Allah E. F. Traditional phytomedicines for gynecological problems used by tribal communities of Mohmand Agency near the Pak-Afghan border area. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia . 2018;28(4):503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khan R. U., Mehmood S., Muhammad A., Mussarat S., Khan S. U. Medicinal plants from flora of Bannu used traditionally by north west Pakistan women’s to cure gynecological disorders. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences . 2015;15(4):553–559. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hussain W., Ullah M., Dastagir G., Badshah L. Quantitative ethnobotanical appraisal of medicinal plants used by inhabitants of lower Kurram, Kurram agency, Pakistan. Avicenna journal of phytomedicine . 2018;8(4):313–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adnan M., Tariq A., Mussarat S., Begum S., AbdEIsalam N. M., Ullah R. Ethnogynaecological assessment of medicinal plants in Pashtun’s tribal society. BioMed Research International . 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/196475.196475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aziz M. A., Adnan M., Khan A. H., Rehman A. U., Jan R., Khan J. Ethno-medicinal survey of important plants practiced by indigenous community at Ladha subdivision, South Waziristan agency, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2016;12(1):p. 53. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shinwari S., Ahmad M., Zhang G., Jahan S., Sultana S. Medicinal plant diversity use for gynecological disorders among the rural communities of Northern Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2017;49(5):1787–1799. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Das D. C., Sinha N. K., Das M. The use of medicinal plants for the treatment of gynaecological disorders in the eastern parts of India. Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Research . 2015;2 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data