Abstract

The iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co) of nitrogenase contains molybdenum, iron, sulfur, and homocitrate in a ratio of 1:7:9:1. In vitro synthesis of FeMo-co has been established, and the reaction requires an ATP-regenerating system, dithionite, molybdate, homocitrate, and at least NifB-co (the metabolic product of NifB), NifNE, and dinitrogenase reductase (NifH). The typical in vitro FeMo-co synthesis reaction involves mixing extracts from two different mutant strains of Azotobacter vinelandii defective in the biosynthesis of cofactor or an extract of a mutant strain complemented with the purified missing component. Surprisingly, the in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co with only purified components failed to generate significant FeMo-co, suggesting the requirement for one or more other components. Complementation of these assays with extracts of various mutant strains demonstrated that NifX has a role in synthesis of FeMo-co. In vitro synthesis of FeMo-co with purified components is stimulated approximately threefold by purified NifX. Complementation of these assays with extracts of A. vinelandii DJ42.48 (ΔnifENX ΔvnfE) results in a 12- to 15-fold stimulation of in vitro FeMo-co synthesis activity. These data also demonstrate that apart from the NifX some other component(s) is required for the cofactor synthesis. The in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co with purified components has allowed the detection, purification, and identification of an additional component(s) required for the synthesis of cofactor.

Nitrogenase, which catalyzes the ATP- and reductant-dependent reduction of dinitrogen to ammonium, is composed of two oxygen-labile metalloproteins: dinitrogenase (MoFe protein, NifDK, or component I) and dinitrogenase reductase (Fe protein, NifH, or component II) (5, 9, 29). Dinitrogenase, an α2β2 tetramer of the nifD and nifK gene products, is specifically reduced by dinitrogenase reductase, a dimer of the nifH gene product, one electron at a time with the concomitant hydrolysis of two MgATPs (18). The electrons transferred to dinitrogenase are channeled to the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co; a unique prosthetic group that contains molybdenum, iron, sulfur, and homocitrate in a ratio of 1:7:9:1), the site for substrate reduction (10, 12, 17, 24, 28, 30).

The products of at least five nitrogen fixation (nif) genes, including nifV, nifB, nifH, nifN, and nifE, are known to be involved in the biosynthesis of FeMo-co (7, 12, 25, 31); the nifQ gene product is also implicated under conditions of molybdenum starvation (15). Interestingly, the genes that encode dinitrogenase (nifD and nifK) are not required for FeMo-co biosynthesis, suggesting that FeMo-co is assembled elsewhere in the cell and is then inserted into the FeMo-co-deficient dinitrogenase (apodinitrogenase) (14, 32). The high degree of sequence similarity between the nifE and nifD sequences and the nifN and nifK sequences suggests that NifNE might serve as a scaffold for at least a portion of FeMo-co biosynthesis (4). This hypothesis is supported by the recent observation that the mobility of NifNE on a native (nondenaturing) electrophoresis gel changes upon the specific addition of purified NifB cofactor (NifB-co) (the Fe- and S-containing FeMo-co precursor as described below) (26). The nifV gene encodes homocitrate synthase (33). Apart from the above gene products, dinitrogenase reductase is also required for FeMo-co biosynthesis, though its exact role in this process is not clear (25, 31).

An in vitro FeMo-co synthesis system that requires an ATP-regenerating system, molybdate, homocitrate, and at least NifB, NifNE, and NifH has been described previously (12, 13, 25, 31). This system has provided a method of assaying for NifB and NifNE activities and homocitrate (12, 23, 31). With the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis system, the product of NifB was purified (27) as a detergent-soluble small molecule termed NifB-co. The requirement for NifB in the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis assay has been shown to be satisfied by the addition of NifB-co (27). The stoichiometric requirement of NifB-co for in vitro FeMo-co synthesis and the incorporation of iron and sulfur from active NifB-co into FeMo-co have clearly demonstrated that NifB-co is an iron-sulfur-containing precursor of FeMo-co (1, 27).

Typically, the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis reaction involves mixing extracts from two different mutants defective in the synthesis of the cofactor or a mutant extract complemented with the purified missing component (12, 23, 27, 31). All the components known to be required for FeMo-co synthesis, from genetic and biochemical analyses, are now available in purified forms. However, a mixture containing only the purified forms of these known components along with MgATP, molybdate, homocitrate, and dithionite was tested and was found to yield very little FeMo-co. This paper reports the finding that NifX, the product of the nifX gene, in conjunction with an as-yet-unidentified factor, greatly stimulates FeMo-co synthesis by the purified components.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

ATP, phosphocreatine, creatine phosphokinase, DNase I, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), leupeptin, dithiothreitol (DTT), homocitric acid lactone, Tris base, Reactive Red 120 agarose, heparin agarose, and N-lauroylsarcosine (sodium salt) were obtained from Sigma, Zwittergent 3-12 (SB-12) and sodium dithionite (DTH) were from Fluka Chemicals. Sephacryl S-100, Sephacryl S-300, Sephadex G-25, and phenyl-Sepharose were from Pharmacia Biotech, Inc. The DEAE-cellulose was Whatman DE-52. All other chemicals were of analytical grade available commercially.

Methods.

All buffers used throughout the purification procedure and cell breakage were deoxygenated as described earlier (31) and contained 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 1 mM DTH unless otherwise specified. Anaerobic conditions were used throughout the protocol, and the temperature was maintained at 4 to 5°C.

Azotobacter vinelandii UW45 (containing a point mutation in the nifB gene), DJ35 (ΔnifE), DJ678 (ΔnifDK ΔnifYENX::kan), DJ42.48 (ΔnifENX ΔvnfE), DJ39 (ΔnifNX34), and CA142 (ΔnifDK ΔnifYENX::kan) have been described previously (1, 3, 6, 16, 22). Cells were grown and derepressed, and extracts were prepared as described previously (23, 26, 28). Except as noted, all crude extracts were made 10% in glycerol and stored as 4- to 5-ml aliquots in anoxic vials at −80°C. The extracts used for the purification of apodinitrogenase, NifNE and NifX, did not contain glycerol.

Klebsiella pneumoniae UN1217 (nif4536) has been described previously (19). The minimal medium, growth conditions, and purification of NifB-co from membranes of strain UN1217 have been described previously (27).

ATP-generating system.

The ATP-generating solution was prepared as described previously (13), at the final pH of 7.4. Dithionite solution (0.1 M) was prepared anaerobically in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). ATP-generating solution, dithionite, and 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM dithionite were mixed in a ratio of 24:1:7, after deoxygenating the ATP-generating solution by repeated evacuation and flushing with argon. This mixture is referred to as ATP-dithionite throughout this paper.

In vitro FeMo-co synthesis and nitrogenase assays.

The reactions were carried out in stoppered, 9-ml serum vials under argon as described earlier (13, 27, 31). One hundred microliters of 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM dithionite, 10 μl of 1 mM Na2MoO4, 20 μl of 5 mM homocitrate (pH 8.0), and 200 μl of ATP-dithionite was added to each vial, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 10 to 15 min. Aliquots of NifB-co (containing 1 nmol of Fe), NifNE (3 μg of protein), apodinitrogenase (12 μg of protein), and dinitrogenase reductase (52 μg of protein) were added to the reaction mixture. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 550 μl. The vials were incubated in a rotary water bath shaker at 30°C for 30 to 35 min to allow FeMo-co synthesis and insertion into apodinitrogenase. An aliquot of extracts of A. vinelandii mutant strains (nif derepressed) or an extract of wild-type A. vinelandii grown in medium containing ammonium (nif repressed) or purified protein component(s) was included in the reaction mixture (where stated in Results and Discussion) as a source of other proteins and/or cofactors. After this incubation, an additional 800 μl of ATP-dithionite solution and 52 μg of purified dinitrogenase reductase (in 5 μl) were injected into each vial. Acetylene reduction assays were carried out at 30°C for 30 min (27, 31), and the ethylene formed was measured with a Shimadzu model GC8A gas chromatograph equipped with a Porapak N (Waters Associates) column.

The activities of the individual purified components were established by assaying the purified form of the component with an appropriate extract of a mutant strain lacking that component. For example, NifNE activity was determined by adding purified NifNE and 200 μl of an extract of strain DJ35 (ΔnifE) to the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis assay (26). NifNE activity is expressed as the nanomoles of ethylene formed per minute per milligram of protein in the NifNE-containing fraction in the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis assays containing an excess of other components (26). A unit of NifB-co activity is defined as 1 nmol of ethylene formed per min when a source of NifB-co is added to in vitro FeMo-co synthesis assays containing 200 μl (2.5 mg of protein) of extract of strain UW45 (nifB) (27). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (11) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Dinitrogenase reductase was purified as described previously, and the activity of dinitrogenase reductase was determined as nanomoles of ethylene formed per minute per milligram of protein in assays containing purified dinitrogenase as described earlier (29).

In vitro FeMo-co insertion assay.

FeMo-co was isolated as described earlier (28). In vitro FeMo-co insertion assays were performed as described previously (22). Apodinitrogenase activity is expressed as the nanomoles of ethylene formed per minute per milligram of protein in the apodinitrogenase-containing fraction in the in vitro FeMo-co insertion assay in the presence of excess FeMo-co (22).

SDS-PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with a 2.8% stacking gel and a 14% resolving gel electrophoresed at 100 V until the bromophenol blue entered the resolving gel and then electrophoresed at 200 V until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel. Low-molecular-weight markers (Bio-Rad) were used.

Immunoblots.

The protocols for immunoblotting and development with modifications (2) have been described previously. Gels were equilibrated in the transfer buffer for at least 5 min and transferred at 4°C to a nitrocellulose membrane at 0.3 A for 1 h.

Production of antibody.

Purified NifX, overproduced in Escherichia coli, was kindly provided by Limin Zheng and Dennis Dean. Antibody to NifX was produced by the Animal Care Unit of the University of Wisconsin Medical School by a Center for Health Sciences-Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol for standard rabbit polyclonal antibody production.

Purification of NifNE and apodinitrogenase.

Apodinitrogenase and NifNE were purified from A. vinelandii UW45 (nifB). The form of apodinitrogenase obtained from UW45 is hexameric (α2β2γ2) and can be activated by purified FeMo-co in the absence of any other factors (22). All buffers used throughout the purification of NifNE and apodinitrogenase contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1.7 mM DTH, and 1 mM DTT (referred to as buffer 1 in this section). Buffer 1 containing 20% glycerol is referred to as buffer 2. All buffers were deoxygenated as described earlier (27, 31). Temperature was maintained at 4 to 5°C, and anoxic conditions were maintained throughout the procedure. The Reactive Red 120 agarose column (4 by 20 cm) was equilibrated in buffer 1. Approximately 320 ml of crude extract from 80 g of strain UW45 cells (nif derepressed) was made 1 mM in DTT and applied to the Reactive Red 120 agarose column at the flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed first with 150 ml of buffer 1 and then with 100 ml of buffer 2 containing 0.1 M NaCl. NifNE and apodinitrogenase were eluted with buffer 2 containing 0.4 M NaCl. Most of the NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities were recovered in approximately 100 ml of 0.4 M NaCl-containing fractions. These fractions were diluted with 3 volumes of buffer 1 and applied to a Q-Sepharose column (2.5 by 20 cm) equilibrated in buffer 2 containing 0.15 M NaCl. The column was washed with 1 column volume of buffer 2 containing 0.15 M NaCl and 1/2 column volume of buffer 2 containing 0.2 M NaCl, and the NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities were eluted with buffer 2 containing 0.35 M NaCl. Most of the activities were recovered in approximately 40 ml of 0.35 M NaCl-containing fractions. Fractions showing NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities were concentrated by ultrafiltration with an Amicon XM100A membrane and applied (in two aliquots) to a Sephacryl S-300 column (2.5 by 99 cm) equilibrated in buffer 2 containing 0.1 M NaCl. The column was operated at a flow rate of approximately 14 ml/h. NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities were recovered in 25-ml fractions collected after 230 ml had eluted from the column. Active fractions were diluted with 2 volumes of buffer 1 and applied at a flow rate of 1 ml/min to a heparin agarose column (1.5 by 20 cm) equilibrated in buffer 1. The column was washed with 1/2 column volume of buffer 1 and 1/2 column volume of buffer 2 containing 50 mM NaCl. NifNE and apodinitrogenase were then eluted with buffer 2 containing 0.3 M NaCl. Most of the NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities were recovered together in fractions, with a total of 15 to 20 ml.

Separation of NifNE and apodinitrogenase.

The combined fractions containing purified NifNE and apodinitrogenase were diluted with 2 volumes of buffer 1 and applied to a Q-Sepharose column (1.5 by 20 cm) equilibrated in buffer 2 containing 0.1 M NaCl. The column was washed with 1/2 column volume each of 0.1 M, 0.15 M, 0.2 M, 0.25 M, 0.3 M, and 0.35 M NaCl in buffer 2. Fractions were assayed for NifNE and apodinitrogenase activities, and active fractions of each were concentrated by ultrafiltration with an Amicon XM100A membrane and stored in liquid N2. NifNE (free of apodinitrogenase) activity was recovered in 0.2 M NaCl fractions, while apodinitrogenase (free of NifNE) activity was recovered in 0.3 M and 0.35 M NaCl fractions.

Purification of NifX from A. vinelandii.

All buffers used throughout the purification of NifX contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 0.1 mM DTH (referred to as buffer 3 in this section). A Reactive Red 120 agarose column (4 by 20 cm) was reduced with buffer 3 containing 1.7 mM DTH, and the column was further washed with 2 column volumes of buffer 3. Approximately 240 ml of crude extract of A. vinelandii UW45 (nif derepressed) was applied to the column at the flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions were assayed for stimulation of the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis reaction with the purified components. NifX was visualized by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-NifX antibody as described above. NifX did not bind to Reactive Red 120 agarose and was recovered in the column flowthrough fractions. The fractions containing NifX were then applied to a Q-Sepharose column (2.5 by 20 cm) equilibrated with buffer 3 containing 0.1 M NaCl. The column was washed with 2 column volumes of 0.1 M NaCl in buffer 3, followed by 1 column volume each of 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 M NaCl in buffer 3, and fractions were collected anaerobically. Most of the NifX eluted with 0.3 M NaCl in buffer 3. The Q-Sepharose fractions showing NifX activity were concentrated by ultrafiltration and applied (in two aliquots) to a Sephacryl S-100 column (2.5 by 96 cm) equilibrated in 0.1 M NaCl in buffer 3, and the column was operated at a flow rate of approximately 15 ml/h. NifX was recovered in the fractions collected after approximately 260 ml. The NifX-active fractions were applied to a Q-Sepharose column (0.75 by 10 cm) equilibrated in buffer 3 containing 0.1 M NaCl. The column was washed with 1 column volume each of 0.1 M and 0.2 M NaCl in buffer 3, and NifX activity was eluted with 0.3 M NaCl in buffer 3. The NifX-active fractions were then applied to a hydroxylapatite column (1.5 by 10 cm) equilibrated with buffer 3 containing 0.1 M NaCl and washed with 1 column volume of the column buffer. The column was developed with 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 mM KPO4 buffer (pH 7.4). Most of the NifX activity eluted with 10 and 25 mM KPO4 buffer. The NifX-active fractions were diluted with equal volumes of 1 M (NH4)2SO4 in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and applied to a phenyl-Sepharose column (1 by 18 cm) equilibrated in 0.5 M (NH4)2SO4 in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The column was eluted with 20 ml each of 0.5, 0.25, 0.2, 0.15, 0.1, and 0.05 M (NH4)2SO4 in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Most of the NifX activity eluted with 0.15 and 0.1 M (NH4)2SO4 in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). A densitometric scan of Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels suggested that the NifX was at least 70% pure. Active fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration and stored at −20°C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

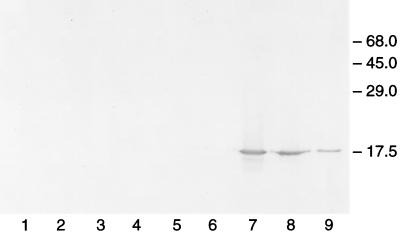

The typical in vitro FeMo-co synthesis reaction involves mixing extracts from two different mutant strains defective in the biosynthesis of the cofactor or an extract of a mutant strain complemented with the purified missing component (23, 26, 27, 31). It has been known, from genetic and biochemical analyses, that FeMo-co synthesis involves the gene products of nifV, nifB, nifH, nifN, and nifE. All of the components known to be required for in vitro FeMo-co synthesis are now available in purified form. Apodinitrogenase, NifNE, NifB-co, and dinitrogenase reductase were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Purified apodinitrogenase, NifNE, and dinitrogenase reductase had specific activities of 1,300, 4,400, and 1,600, respectively. To determine if only the above-mentioned components were required for the biosynthesis of the cofactor, the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis assay was performed in the presence of these purified components (purified system). Surprisingly, the purified system failed to generate significant FeMo-co (Table 1). When the components (NifNE, apodinitrogenase, NifB-co, and dinitrogenase reductase) used in the above experiment were assayed individually by complementation with extracts of appropriate mutant strains, all components were very active (see footnote a of Table 1), suggesting that the lack of FeMo-co synthesis was not due to the addition of an inactive component to these assays. These results clearly suggest that some component(s) required for the synthesis of FeMo-co is missing in the purified system. Cell extracts of various mutant strains defective in the biosynthesis of FeMo-co or an extract of A. vinelandii wild type grown in the medium containing ammonium (nif repressed) was then used to complement assay mixtures containing only purified components. Most of the extracts stimulated FeMo-co synthesis activity 2- to 3-fold, while the extract of strain DJ35 (ΔnifE) stimulated activity 28-fold (Table 1). Each of the mutants examined, except strain DJ35, had a deletion of various nif genes including nifX. When the extracts of these mutants were analyzed for the presence of NifX by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses with antibody to NifX, only DJ35 showed the presence of NifX (Fig. 1, lane 7). These results suggest that NifX participates in the in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co and that it can be partly replaced by another protein(s) in the extract. Curiously, the deletion of nifX has no significant effect on the phenotype of A. vinelandii (16), suggesting that another protein(s) can substitute for the function of NifX in vivo to some extent and that the two- to threefold stimulation of activity (Table 1) by these extracts may be due to the effect of these proteins.

TABLE 1.

In vitro synthesis of the FeMo-co with purified components and the effect of addition of extracts of various Nif− strainsa

| Cell extract addedb | Genotype | Activity (nmol of ethylene formed/min) | Fold stimu-lation |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | 0.46 | 1.0 |

| DJ4248 | ΔnifENX ΔvnfE | 1.19 | 2.6 |

| CA142 | ΔnifDK ΔnifYENX::kan | 1.21 | 2.6 |

| DJ678 | ΔnifDK ΔnifYENX::kan | 0.95 | 2.1 |

| DJ39 | ΔnifNX34 | 0.85 | 1.8 |

| UW NH4+-grown | nif repressed | 0.80 | 1.7 |

| DJ35 | ΔnifE | 12.75 | 27.7 |

The reaction mixture contained 100 nmol of homocitrate, 10 nmol of molybdate, 200 μl of ATP-dithionite solution as defined in Materials and Methods, NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe), apodinitrogenase (12 μg of protein), NifNE (3 μg of protein), and dinitrogenase reductase (52 μg of protein) in a final volume of 550 μl. Twelve micrograms of dinitrogenase gave 15.5 nmol of ethylene formed/min when assayed with excess purified FeMo-co, 3 μg of NifNE gave 13.2 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with extract of strain DJ35 (ΔnifE), NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe) gave 25.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with an extract of strain UW45 (nifB mutant), and 52 μg of dinitrogenase reductase gave 82.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with purified dinitrogenase, as described in Materials and Methods.

Where noted, 200 μl of extract (2.2 to 2.6 mg of protein) from the indicated strain was added.

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot analysis of SDS gel developed with antibody to NifX. Lane 1, purified NifNE (3 μg of protein); lane 2, extract of DJ42.48 (27 μg of protein); lane 3, extract of CA142 (30 μg of protein); lane 4, extract of DJ678 (32 μg of protein); lane 5, extract of DJ39 (28 μg of protein); lane 6, extract of UW (NH4+ grown) (26 μg of protein); lane 7, extract of DJ35 (29 μg of protein); lane 8, extract of UW45 (31 μg of protein); lane 9, purified NifX (0.4 μg of protein). Numbers at right show molecular masses in kilodaltons.

In order to determine if NifX alone could stimulate the synthesis of FeMo-co by purified components, NifX was purified as described in Materials and Methods and added to the in vitro FeMo-co synthesis reaction mixture. As shown in Table 2, purified NifX stimulated the activity of the purified system only two- to threefold. Addition of increasing amounts of purified NifX did not increase the fold stimulation. Exposure of NifX to air for 15 min or heat treatment at 50°C for 5 min had no effect on its ability to stimulate in vitro FeMo-co synthesis. On the other hand, heat treatment at 60°C for 5 min inactivated NifX activity (data not shown). These data suggest that NifX is O2 stable but heat labile.

TABLE 2.

Effect of NifX on in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co with purified componentsa

| NifX added (μg of protein) | DJ42.48 extract (mg of protein) | Activity (nmol of ethylene formed/min) | Fold stimulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | 0.52 | 1.0 |

| 1.9 | 1.48 | 2.8 | |

| 3.8 | 1.77 | 3.4 | |

| 7.5 | 1.69 | 3.2 | |

| 2.2 | 1.40 | 2.7 | |

| 1.9 | 2.2 | 6.52 | 12.5 |

| 3.8 | 2.2 | 7.34 | 14.1 |

| 7.5 | 2.2 | 8.04 | 15.5 |

The reaction mixture contained 100 nmol of homocitrate, 10 nmol of molybdate, 200 μl of ATP-dithionite solution, NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe), apodinitrogenase (12 μg of protein), NifNE (3 μg of protein), and dinitrogenase reductase (52 μg of protein) in a final volume of 550 μl. Twelve micrograms of apodinitrogenase gave 15.5 nmol of ethylene formed/min when assayed with excess purified FeMo-co, 3 μg of NifNE gave 13.2 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with an extract of strain DJ35 (ΔnifE), NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe) gave 25.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with an extract of strain UW45 (nifB mutant), and 52 μg of dinitrogenase reductase gave 82.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with purified dinitrogenase, as described in Materials and Methods.

The stimulation of in vitro FeMo-co synthesis activity by addition of purified NifX to the purified system was greater when an extract of A. vinelandii DJ42.48 was added in conjunction with purified NifX. The strain DJ42.48 has deletions of nifENX and vnfE (vnfE is the gene encoding the nifE homolog of the vanadium nitrogenase system). As shown in Fig. 1, there is no immunologically detectable NifX in the extract of this strain. The extract of strain DJ42.48 alone gave a small (2.7-fold) stimulation of FeMo-co synthesis activity when added to the purified system. However, when purified NifX and the extract of strain DJ42.48 were added together to the purified system, up to a 15-fold stimulation of in vitro FeMo-co synthesis was observed (Table 2). These data suggest that, apart from NifX, some other component(s) may be necessary for in vitro FeMo-co synthesis. From our preliminary data, it seems that the unknown component(s) in the extract of strain DJ42.48 (ΔnifENX ΔvnfE) is very sensitive to DTH concentrations (1.7 mM and higher) normally used during purification of O2-labile proteins. The unknown component(s) was partially purified with anoxic buffers containing 0.1 mM DTH and 0.2 mM DTT. The unknown component(s) did not bind to the Reactive Red 120 agarose or heparin agarose columns and was recovered in the flowthrough fractions from these columns. The unknown component(s) was found to bind to a Q-Sepharose column equilibrated in 0.1 M NaCl in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer. The column was then developed with 0.1 M, 0.3 M, and 0.5 M NaCl in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Most of the unknown component(s) was recovered in 0.3 M NaCl in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer wash. The active fractions, as judged by the ability to stimulate in vitro FeMo-co synthesis with purified components, were then pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration with an XM50 membrane and applied to a Sephacryl S-100 column (2.5 by 96 cm) equilibrated in 0.1 M NaCl in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer. The unknown component(s) was recovered in fractions collected after approximately 235 ml. When the FeMo-co synthesis assays with purified components and NifX were complemented with varying amounts of partially purified unknown component (Table 3), the activity increased in proportion to the amount of protein added. These data suggest that the unknown component seems to be the limiting factor in these assays.

TABLE 3.

Effect of partially purified unknown component on in vitro synthesis of FeMo-co with purified components plus NifXa

| NifX added (μg of protein) | Partially purified unknown component (mg of protein) | Activity (nmol of ethylene formed/min) | Fold stimulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | 0.55 | 1.0 |

| 2.1 | 1.60 | 2.9 | |

| 4.2 | 1.79 | 3.2 | |

| 0.21 | 1.56 | 2.8 | |

| 0.42 | 1.90 | 3.4 | |

| 2.1 | 0.21 | 4.18 | 7.6 |

| 2.1 | 0.42 | 7.54 | 13.7 |

| 2.1 | 0.64 | 10.42 | 18.9 |

| 2.1 | 0.85 | 12.55 | 22.8 |

The reaction mixture contained 100 nmol of homocitrate, 10 nmol of molybdate, 200 μl of ATP-dithionite solution, NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe), apodinitrogenase (12 μg of protein), NifNE (3 μg of protein), and dinitrogenase reductase (52 μg of protein) in a final volume of 550 μl. Twelve micrograms of apodinitrogenase gave 15.5 nmol of ethylene formed/min when assayed with excess purified FeMo-co, 3 μg of NifNE gave 13.2 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with an extract of strain DJ35 (ΔnifE), NifB-co (1 nmol of Fe) gave 25.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with an extract of strain UW45 (nifB mutant), and 52 μg of dinitrogenase reductase gave 82.4 nmol of ethylene/min when assayed with purified dinitrogenase, as described in Materials and Methods.

What is the role of NifX in FeMo-co biosynthesis? We have considered the following possible roles of NifX in FeMo-co synthesis. On the basis of primary sequence similarity of NifNE to NifKD (dinitrogenase), it has been suggested that NifNE provides a scaffold for the biosynthesis of FeMo-co (3, 6). NifNE forms a heterotetrameric (α2β2) complex like NifKD (22, 23). NifX has some sequence similarity to NifY (16). The nifY gene is located in the same transcription unit as the dinitrogenase structural genes (nifD and nifK), whereas the nifX gene is located in the same transcription unit as nifE and nifN (16, 21). These similarities and the attachment of NifY in K. pneumoniae to the α2β2 form of apodinitrogenase to generate the α2β2γ2 form of apodinitrogenase suggest that NifX may be attached to NifNE at some stage of FeMo-co biosynthesis and may serve as a molecular prop for the biosynthesis of FeMo-co or its precursor. Analysis of the purified NifNE preparations by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibody to NifX showed no detectable NifX in the purified NifNE preparations used for in vitro biosynthesis of FeMo-co (Fig. 1, lane 1), which demonstrates that NifX is not tightly bound to NifNE, as purified from mutant strain UW45. Purified NifNE is able to bind NifB-co (26), suggesting that the presence of NifX is not essential for the binding of NifB-co to NifNE. It is possible that NifX is associated with NifNE in vivo but that this complex is not stable enough to withstand the purification protocol. Analysis of crude extracts of strain UW45 (nifB) by anaerobic Sephacryl S-300 column chromatography and anoxic native PAGE followed by immunoblotting with antibody to NifX failed to demonstrate any association of NifX with NifNE (data not shown). These results do not rule out any transient association of NifX with NifNE during FeMo-co biosynthesis. It is also possible that the NifX might be involved in effective transfer of the FeMo-co precursor from the NifNE complex to dinitrogenase reductase or another protein where further steps of FeMo-co synthesis are completed.

On the basis of sequence comparison among nifB, nifX, and nifY, Moreno-Vivian et al. (20) suggested that NifX might be involved in maturation and/or stability of FeMo-co. An insertional mutation in the nifX gene of K. pneumoniae had little effect on the nitrogenase activity of the strain (8). These results are similar to those for deletion of the nifX gene of A. vinelandii (16). On the other hand, the overexpression of the wild-type nifX region inhibited Nif protein synthesis and protein accumulation in K. pneumoniae (8). The present in vitro work suggests that those regulatory effects might be indirect. For example, the absence or overexpression of NifX might perturb FeMo-co synthesis, which might serve as a regulatory signal. It is also possible that NifX from A. vinelandii and that from K. pneumoniae differ in their physiological roles, as their sequence identity is not high.

Conclusion.

We have shown in the present work the requirement of NifX for in vitro FeMo-co synthesis. By use of the purified FeMo-co synthesis system, we have established an assay for NifX activity. The purified system has also allowed the detection of yet another component that seems to be required for in vitro FeMo-co synthesis. The identification and characterization of this unknown component are currently being undertaken. Use of the purified FeMo-co synthesis system should help identify other proteins that play roles in cofactor biosynthesis, in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work from our laboratories described here has been supported by NIH grant GM 35332 and USDA NRI grant 98-35305-6685 to P.W.L. and by NSF grant MCB-9604446 to G.P.R.

We thank Dennis Dean for generously providing A. vinelandii mutant strains. We are grateful to Paul Bishop and R. Premakumar for the construction of A. vinelandii CA142. We thank Dennis Dean and Limin Zheng for purified overexpressed NifX used for antibody production. We also thank Winston Brill for his continued interest in the FeMo-co project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen R M, Chatterjee R, Ludden P W, Shah V K. Incorporation of iron and sulfur from NifB cofactor into the iron-molybdenum cofactor of dinitrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26890–26896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandner J P, McEwan A G, Kaplan S, Donohue T. Expression of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 structural gene. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:360–368. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.360-368.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brigle K E, Setterquist R A, Dean D R, Cantwell J S, Weiss M C, Newton W E. Site-directed mutagenesis of the nitrogenase MoFe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7066–7069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigle K E, Weiss M C, Newton W E, Dean D R. Products of the iron-molybdenum cofactor-specific biosynthetic genes, nifE and nifN, are structurally homologous to the products of the nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein genes, nifD and nifK. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1547–1553. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1547-1553.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulen W A, LeComte J R. The nitrogenase system from Azotobacter: two enzyme requirements for N2 reduction, ATP dependent H2 evolution and ATP hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:979–986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.3.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean D R, Bolin J T, Zheng L. Nitrogenase metalloclusters: structures, organization, and synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6737–6744. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6737-6744.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filler W A, Kemp R M, Ng J C, Hawkes T R, Dixon R A, Smith B E. The nifH gene product is required for the synthesis or stability of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Biochem. 1986;160:371–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosink M M, Franklin N M, Roberts G P. The product of the Klebsiella pneumoniae nifX gene is a negative regulator of the nitrogen fixation (nif) regulon. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1441–1447. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1441-1447.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hageman R V, Burris R H. Nitrogenase and nitrogenase reductase associate and dissociate with each catalytic cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2699–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkes T R, McLean P A, Smith B E. Nitrogenase from nifV mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae contains an altered form of the iron-molybdenum cofactor. Biochem J. 1984;217:317–321. doi: 10.1042/bj2170317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill H D, Straka J G. Protein determination using bicinchoninic acid in the presence of sulfhydryl reagents. Anal Biochem. 1988;170:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoover T R, Imperial J, Ludden P W, Shah V K. Homocitrate is a component of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2768–2771. doi: 10.1021/bi00433a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imperial J, Hoover T R, Madden M S, Ludden P W, Shah V K. Substrate reduction properties of dinitrogenase activated in vitro are dependent upon the presence of homocitrate or its analogues during iron-molybdenum cofactor synthesis. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7796–7799. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperial J, Shah V K, Ugalde R A, Ludden P W, Brill W J. Iron-molybdenum cofactor synthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii Nif− mutants. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1784–1786. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1784-1786.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperial J, Ugalde R A, Shah V K, Brill W J. Role of the nifQ gene product in the incorporation of molybdenum into nitrogenase in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:187–194. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.187-194.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson M R, Brigle K E, Bennett L T, Setterquist R A, Wilson M S, Cash V L, Beynon J, Newton W E, Dean D R. Physical and genetic map of the major nif gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1017–1027. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.1017-1027.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Rees D C. Crystallographic structure and functional implications of the nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein from Azotobacter vinelandii. Nature. 1992;360:553–560. doi: 10.1038/360553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljones T, Burris R H. Nitrogenase: the reaction between the Fe protein and bathophenanthrolinedisulfonate as a probe for interactions with MgATP. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1866–1872. doi: 10.1021/bi00603a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacNeil T, MacNeil D, Roberts G P, Supiano M A, Brill W J. Fine-structure mapping and complementation analysis of nif (nitrogen fixation) genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:253–266. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.1.253-266.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno-Vivian C, Schmehl M, Masepohl B, Arnold W, Klipp W. DNA sequence and genetic analysis of the Rhodobacter capsulatus nifENX gene region: homology between NifX and NifB suggests involvement of NifX in processing of the iron-molybdenum cofactor. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;216:353–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00334376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muchmore S W, Jack R F, Dean D R. Developments in the analysis of nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor biosynthesis. In: Hausinger R P, editor. Mechanisms of metallocenter assembly. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers, Inc.; 1996. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paustian T D, Shah V K, Roberts G P. Apo-dinitrogenase: purification, association with a 20-kilodalton protein, and activation by the iron-molybdenum cofactor in the absence of dinitrogenase reductase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3515–3522. doi: 10.1021/bi00466a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paustian T D, Shah V K, Roberts G P. Purification and characterization of the nifN and nifE gene products from Azotobacter vinelandii mutant UW45. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6082–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawlings J, Shah V K, Chisnell J R, Brill W J, Zimmermann R, Münck E, Orme-Johnson W H. Novel metal cluster in the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:1001–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson A C, Dean D R, Burgess B K. Iron-molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii requires the iron protein of nitrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14327–14332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roll J T, Shah V K, Dean D R, Roberts G P. Characteristics of NIFNE in Azotobacter vinelandii strains. Implications for the synthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of dinitrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4432–4437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah V K, Allen J R, Spangler N J, Ludden P W. In vitro synthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Purification and characterization of NifB cofactor, the product of the NifB protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1154–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah V K, Brill W J. Isolation of an iron-molybdenum cofactor from nitrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah V K, Brill W J. Nitrogenase. IV. Simple method of purification to homogeneity of nitrogenase components from Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;305:445–454. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(73)90190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah V K, Chisnell J R, Brill W J. Acetylene reduction by the iron-molybdenum cofactor from nitrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;81:232–236. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah V K, Imperial J, Ugalde R A, Ludden P W, Brill W J. In vitro synthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1636–1640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ugalde R A, Imperial J, Shah V K, Brill W J. Biosynthesis of iron-molybdenum cofactor in the absence of nitrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:888–893. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.3.888-893.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng L, White R H, Dean D R. Purification of the Azotobacter vinelandii nifV-encoded homocitrate synthase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5963–5966. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5963-5966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]