Abstract

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to a lockdown period. Confinement periods have been related to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. Our study aimed to determine weight change, changes in eating and exercise habits, the presence of depression and anxiety, and diabetes mellitus (DM) status in a cohort of patients with obesity.

Methods

The study was undertaken in nine centers of Collaborative Obesity Management (COM) of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) in Turkey. An e-survey about weight change, eating habits, physical activity status, DM status, depression, and anxiety was completed by patients. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) score was used to determine physical activity in terms of metabolic equivalents (METs). A healthy nutrition coefficient was calculated from the different categories of food consumption. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) Questionnaire were used for determining depression and anxiety, respectively.

Results

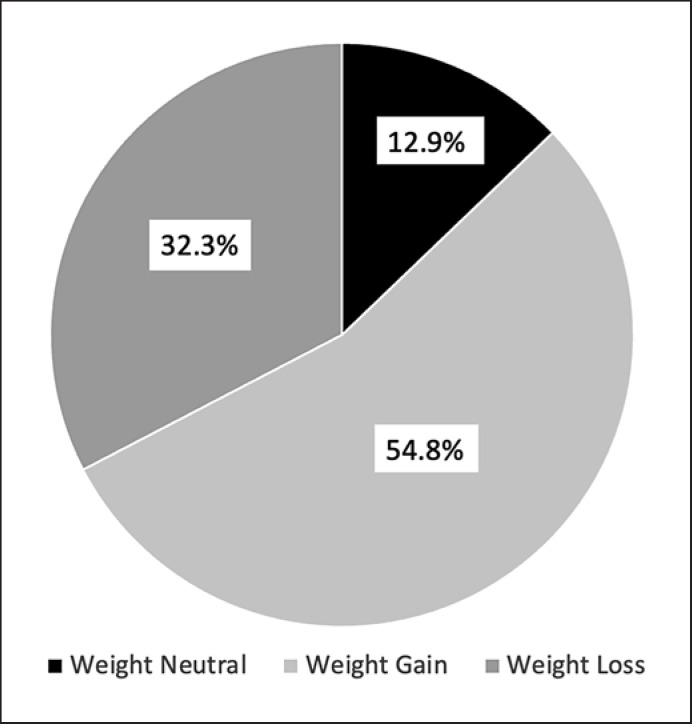

Four hundred twenty-two patients (age 45 ± 12.7 years, W/M = 350/72) were included. The healthy nutrition coefficient before the pandemic was 38.9 ± 6.2 and decreased to 38.1 ± 6.4 during the pandemic (p < 0.001). Two hundred twenty-nine (54.8%) patients gained weight, 54 (12.9%) were weight neutral, and 135 (32.3%) lost weight. Patients in the weight loss group had higher MET scores and higher healthy nutrition coefficients compared with the weight gain and weight-neutral groups (p < 0.001). The PHQ and GAD scores were not different between the groups. Percent weight loss was related to healthy nutrition coefficient (CI: 0.884 [0.821–0.951], p = 0.001) and MET categories (CI: 0.408 [0.222–0.748], p = 0.004). One hundred seventy patients had DM. Considering glycemic control, only 12 (8.4%) had fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL and 36 (25.2%) had postprandial BG <160 mg/dL. When patients with and without DM were compared in terms of dietary compliance, MET category, weight loss status, PHQ-9 scores, and GAD-7 scores, only MET categories were different; 29 (11.7%) of patients in the nondiabetic group were in the highly active group compared with 5 (2.9%) in the diabetic group.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 lockdown resulted in weight gain in about half of our patients, which was related to changes in physical activity and eating habits. Patients with DM who had moderate glycemic control were similar to the general population in terms of weight loss but were less active.

Keywords: Obesity, COVID-19, Lockdown, Weight change, Lifestyle behaviors, Anxiety, Depression

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to a lockdown period of around 2 months between March and May 2020 in Turkey, as in many parts of the world. Although there seemed to be positive influences on decreasing the transmission of COVID-19 during the lockdown, there have been other consequences coming with changes in the lifestyle of people. Especially evident were the changes in physical activity [1, 2, 3], eating behaviors [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12], problems in reaching healthcare services, and increases in psychological, mood, and sleep disturbances due to the increased stress of both being confined and fear of the COVID-19 infection itself [13, 14, 15].

Weight gain was found to be related to increased snacking, increased consumption of unhealthy food, and increased number of meals in the general population [4, 10]. The changes in eating and physical activity patterns were inevitable due to being restricted to food products with a longer shelf-life, which are commonly unhealthy and rich in calories, and also the unavailability of gyms and outdoor sports facilities [16]. However, the psychological state of people was possibly more effective. There is a complex but intriguing relationship between psychological state, eating habits, physical activity state, and sleep quality [17, 18].

There were also problems in reaching healthcare services because hospitals were already overwhelmed with patients with COVID-19 and there were difficulties in giving service to other individuals who were seeking care. Second, patients tried to avoid going to hospitals due to the fear of contracting COVID-19 [19].

Considering the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on a population with obesity, there may be some different aspects compared with the normal population. People with obesity may be more cautious about their eating and exercise habits because they have previously been involved in these aspects and have developed certain lifestyle behaviors. On the other hand, the effect might be just the opposite where people with obesity may be affected by stress and exhibit patterns of emotional eating. It has been previously shown that this population is more vulnerable to psychological stress and emotional eating and has an increased risk of gaining weight [10]. A few studies have addressed the status of people with obesity during the pandemic. A study from Texas determined the issues about substance use, mental health, and weight-related behaviors, showing that most of the participants had increased depression and anxiety, an increased rate of emotional eating, and difficulty in achieving their weight goals [20].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a prominent complication of obesity. All the unfavorable aspects of the pandemic probably affect the course of diabetes because, being a metabolic complication, changes in eating and physical activity habits may directly affect the course of DM. There has been some data published about the diabetic population previously, indicating that there is increased anxiety, less exercise, but no weight gain or deterioration of blood glucose levels in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes [21].

The aim of the study was to determine weight status, changes in weight-related behaviors such as eating patterns, diet quality, emotional eating, physical activity, degree of depression and anxiety, status of reaching healthcare during the pandemic, concerns about COVID-19, and details about diabetes status in patients with DM during the COVID-19 lockdown in a group of individuals with obesity who are being followed at Obesity Management Centers in Turkey.

Methods

The study was undertaken in nine centers of Collaborative Obesity Management (COM) of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) in Turkey. These centers were from different regions of Turkey, including Istanbul, Bursa, and Zonguldak. A power analysis was conducted and a target responder rate of 385 was determined. Each center was asked to recruit at least 45 patients. Participants were randomly selected from among patients who had been followed at the centers for at least 3 months and had regularly attended appointments before March 11, 2020, when the first case was detected in Turkey. The inclusion criteria were all patients with obesity who could read and answer the questions online. An e-survey was prepared using Google forms and was sent to patients who were followed at these centers via e-message or e-mail by the attending physicians or nurses.

The Questionnaire Consisted of Different Sections

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The first part included questions related to the sociodemographic profile of the participants (e.g., age, sex, marital status, educational level, number of children).

Obesity History

Obesity history included parts about the duration of obesity, medications used by the patients, complications of obesity, and frequency of follow-up for obesity.

Weight Change during the Pandemic

Both weights before and during the pandemic and height were self-reported by the participants. Their body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (kg) by the height2 (m2).

Healthcare/Medication Availability during the Pandemic

Patients were asked whether they could obtain all their medications, whether they could reach their physicians, and whether they could go to hospitals and undergo lab tests during the pandemic.

Eating Habits during the Pandemic

Eating habits were evaluated by focusing on the quantity and quality of different types of food (i.e., bakery, red meat, chicken/fish, deserts, vegetables) participants consumed before and during the lockdown. The frequencies for each group were asked in the questionnaire as every meal, every day, 4–5 times/week, 2–3 times/week, once per week, 2–3 times/month, and less than once per month. These frequencies were classified using the Likard scale. Bakery, red meat, sugar-containing drinks, packaged food, and sweets were designated as unhealthy foods, and fish/chicken, vegetables, and fruits were designated as healthy foods. For unhealthy foods, a score of 1–7 was given, increasing from the commonest consumption to the least common consumption (every meal = 1; every day = 2; 4–5 times/week = 3; 2–3 times/week = 4; once per week = 5; 2–3 times/month = 6; less than once per month = 7). For the healthy foods, a score of 1–7 was given, increasing from the least common consumption to the commonest consumption (less than once per month = 1; 2–3 times/month = 2; once per week = 3; 2–3 times/week = 4; 4–5 times/week = 5; every day = 6; every meal = 7). A healthy nutrition coefficient was obtained by adding all these scores for each individual. One score for the period before the pandemic and another score for during the pandemic were obtained.

Physical Activity Status

Physical activity was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), determining the amount of vigorous and moderate activity, walking, and sitting during the previous 7 days of the pandemic [22]. The total number of metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes was calculated from the raw data. Also, MET categories were determined from the raw data as low, moderate, and high.

COVID-19-Related Concerns

Questions regarding the infection status of the patients and their fear about COVID-19 were included.

DM Status

Patients who had DM were asked in detail about the type of their diabetes, the medications they were using, the complications, their ability to reach healthcare, their physicians, and their medications. Questions were asked regarding their blood glucose status, including A1c levels, the frequency of their blood glucose measurements, the results of their fasting and postprandial glucose readings, hypoglycemic events, and whether they had any acute diabetic complications.

Depression Status

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 [23], which has been validated in Turkish, was used [24]. A cut-off of 10 was taken to describe the patients as having depression. Patients who had a score of ≥10 were considered to have depression.

Anxiety Status

The validated Turkish version [25] of the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 questionnaire [26] was used to assess anxiety. A cut-off of 10 was taken for GAD-7. Patients with a score ≥10 were considered to have anxiety. Also, questions about smoking and sleep status were added.

The questionnaire was prepared in Turkish. The questionnaire required approximately 20 min to complete. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participating in the study. The study was approved by the Local Institutional Board at Koç University, Istanbul (approval number: 2020.268.IRB1.091).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25, Chicago, IL, USA) program. Mainly, descriptive analyses were performed to determine the frequencies of categorical variables as percentages. Also, ordinal variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The distribution of variables was measured using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For the analysis of quantitative independent data, in normal distribution, we performed Student's t test. In nonnormal distribution, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney U test for the analysis of quantitative independent data. Fisher's exact χ2 test was used for the analysis of qualitative independent data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were performed to determine the factors affecting weight loss status. In univariate analysis, percentage weight loss, age, education status, MET category, dietary compliance, and nutrition coefficient were evaluated. Multivariate analyses were performed for factors that were significant in univariate analysis. Statistically significant results were defined as p < 0.05. The confidence level was set at 95%.

Results

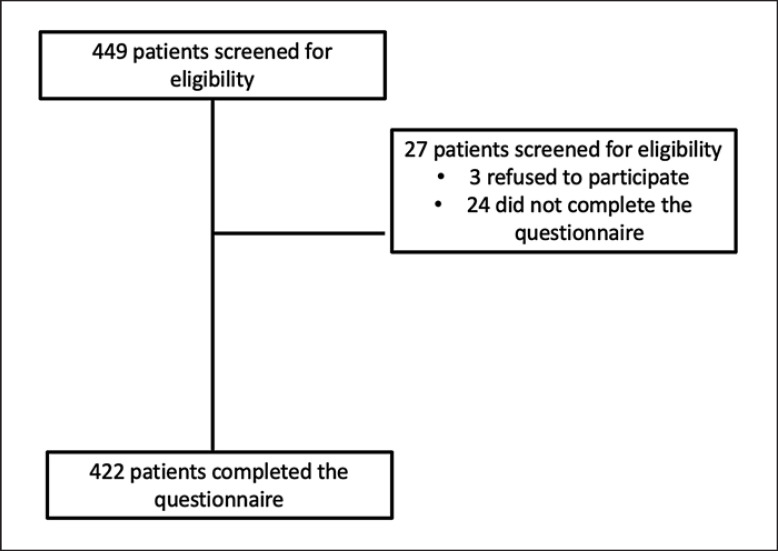

A total of 449 patients were reached, of whom only 422 patients answered all the questions in the questionnaire. A flowchart of the recruitment is given in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

A flowchart of the recruitment of participants in the study.

The sociodemographic variables of the population are presented in Table 1. Data about physician visits, treatment for obesity, and complications of obesity were also included in Table 1.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic variables, MET categories, PHQ-9, GAD-7 scores, and categories of the population

| Variables | N = 422 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 45±12.7 |

| Women/Men, n | 350/72 |

| Education status, n (%) | 153 (37.1) |

| Primary | 46 (11.2) |

| Middle | 106 (25.7) |

| High school | 76 (18.4) |

| University | 13 (3.2) |

| College student | 11 (2.7) |

| Postgraduate | 7 (1.7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 289 (69.6) |

| Never married | 85 (20.5) |

| Divorced | 25 (6) |

| Single | 16 (3.9) |

| Duration of obesity, years | 7.3±7.7 (0.02–45) |

| Physician visits, n (%) | |

| Regularly | 241 (57.1) |

| Sometimes or rarely | 145 (34.4) |

| Never | 36 (8.5) |

| Therapy for obesity, n (%) | |

| Diet | 68 (16.7) |

| Exercise | 4 (1.0) |

| Medications | 18 (4.4) |

| Diet + exercise | 99 (24.3) |

| Diet + exercise + behavioral therapy | 33 (6.1) |

| Diet + exercise + medications | 82 (20.1) |

| Bariatric surgery | 104 (25.5) |

| Complications, n (%) | |

| DM | 174 (41.2) |

| Hypertension | 160 (37.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 108 (25.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 30 (7.1) |

| Fatty liver disease | 60 (14.2) |

| Sleep apnea | 35 (8.2) |

| Asthma | 58 (13.7) |

| Cholelithiasis | 18 (4.2) |

| Joint problems | 85 (20.1) |

| Depression | 61 (14.4) |

| Cancer | 5 (1.1) |

| PCOS | 17 (4.2) |

| Sterility | 3 (0.7) |

| GER | 47 (11.1) |

| Varicose veins | 34 (8.5) |

| BMI before pandemic, kg/m2 | 36.8±7.9 |

| BMI during pandemic, kg/m2 | 36.6±7.9 |

| IPAQ (average MET) | 633.5±1,169.6 |

| MET category, n (%) | |

| Low | 304 (72.0) |

| Moderate | 84 (19.9) |

| High | 34 (8.1) |

| PHQ-9 (total score) | 7.7±5.9 |

| PHQ-9 category, n (%) | |

| <10 | 302 (71.6) |

| ≥10 | 120 (28.4) |

| GAD-7 (total score) | 5.6±5.1 |

| GAD-7 category, n (%) | |

| <10 | 342 (81.0) |

| ≥10 | 80 (19.0) |

BMI, body mass index; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MET, metabolic equivalent; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder.

During the pandemic period, 201 people (48.8%) never left their house and 39 people (9.5%) spent more than 5 h outside their houses. Three hundred fifteen (80.2%) patients had no difficulty in obtaining their medications during the pandemic; the remainder had problems to some extent. Two hundred thirty-one (71.5%) patients were compliant with their medications more than 80% of the time, but 56 (20.1%) were not compliant at all. Three hundred two (83.7%) did not quit or decrease the dose of their medications during the pandemic; 161 (41.2%) had problems reaching their physician; and only 142 (35.4%) had no problems reaching hospitals for laboratory tests. Two hundred eight (64%) patients did not go to hospitals due to the fear of COVID-19 transmission.

The number of meals during the pandemic (3.8 ± 1.7) increased compared with before the pandemic (3.3 ± 1.3) (p < 0.001). When compliance with diet during the pandemic was inquired, 122 patients (29.8%) were never compliant with their diet during the pandemic, 88 (21.5%) were rarely compliant, and 85 (20.8%) were frequently compliant.

The frequencies of different kinds of foods (bakery, red meat, fish/chicken, vegetables, fruits, sugar-containing drinks, packaged food such as potato chips and biscuits, deserts) before and during the pandemic were also questioned and are shown in Table 2. The healthy nutrition coefficient before the pandemic was 38.9 ± 6.2. It decreased to 38.1 ± 6.4 during the pandemic (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

The frequencies of different kinds of foods (bakery, red meat, fish/chicken, vegetables, fruits, sugar containing drinks, package food like potato chips and biscuits, desserts) before and during the pandemic

| Before |

During |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| every meal | every day | 4–5 times/week | 2–3 times/week | once a week | 2–3 times/month | once a month | every meal | every day | 4–5 times/week | 2–3 times/week | once a week | 2–3 times/month | once a month | p value | |

| Bakery | 11 (2.7) | 28 (6.9) | 28 (6.9) | 61 (15.1) | 96 (23.8) | 88 (21.8) | 92 (22.8) | 9 (2.3) | 43 (11.1) | 46 (11.9) | 85 (22.0) | 78 (20.2) | 60 (15.5) | 65 (16.8) | <0.0001 |

| Red meat | 6 (1.5) | 22 (5.4) | 43 (10.5) | 121 (29.6) | 142 (34.7) | 48 (11.7) | 27 (6.6) | 4 (1.0) | 20 (5.2) | 52 (13.5) | 120 (31.2) | 119 (30.9) | 43 (11.2) | 27 (7.0) | 0.13 |

| Fish/chicken | 9 (2.2) | 11 (2.7) | 44 (10.7) | 164 (40) | 127 (31) | 33 (8) | 22 (5.4) | 5 (1.3) | 12 (3.1) | 55 (14.2) | 160 (41.5) | 106 (27.5) | 26 (6.7) | 22 (5.7) | 0.13 |

| Vegetables | 29 (7.1) | 138 (33.7) | 95 (23.2) | 108 (26.3) | 25 (6.1) | 7 (1.7) | 8 (2.0) | 33 (8.5) | 136 (35.1) | 102 (26.4) | 72 (18.6) | 29 (7.5) | 9 (2.3) | 6 (1.6) | 0.006 |

| Fruits | 34 (8.3) | 176 (41.7) | 89 (21.7) | 70 (17.1) | 25 (6.1) | 7 (1.7) | 9 (2.2) | 23 (6.0) | 175 (45.5) | 88 (22.9) | 41 (10.6) | 31 (8.1) | 18 (4.7) | 9 (2.3) | 0.13 |

| Sugary drinks | 14 (3.7) | 23 (6) | 30 (7.9) | 44 (11.5) | 39 (10.2) | 52 (13.6) | 179 (47) | 10 (2.7) | 32 (8.8) | 35 (9.6) | 43 (11.8) | 28 (7.7) | 38 (10.4) | 178 (48.9) | 0.31 |

| Package food (potato chips/biscuits) | 9 (2.2) | 23 (6) | 28 (7.3) | 55 (14.3) | 50 (13) | 64 (16.7) | 155 (40.4) | 8 (2.2) | 32 (8.6) | 38 (10.3) | 52 (14.1) | 36 (9.7) | 44 (11.9) | 160 (43.2) | 0.02 |

| Desserts | 8 (2.0) | 28 (7.1) | 38 (9.6) | 70 (17.8) | 84 (21.3) | 74 (18.8) | 92 (23.4) | 9 (2.4) | 42 (11.1) | 42 (11.1) | 65 (17.2) | 63 (16.7) | 77 (20.4) | 79 (21) | 0.002 |

The sleep time during the pandemic was around 6–8 h in 218 patients (52.4%) and 8–10 h in 105 (25.2%) patients. Seventy-eight (18.7%) patients were actively smoking during the pandemic. One hundred two (39.6%) patients had negative thoughts about COVID-19. Of the entire cohort, 389 (94.9%) did not have a COVID-19 infection. Two hundred two (48.5%) patients were psychologically affected by the pandemic.

Physical activity status was determined using the MET category. The average MET scores and the MET categories are shown in Table 1. Most patients seemed to be in the low MET category.

The average PHQ and GAD-7 scores are shown in Table 1. The patients were categorized using a cut-off of 10 for both scales, and the frequencies are presented in Table 1.

Patients were then categorized as to their weight loss status. The distribution according to the weight loss status is shown in Figure 2. When different variables such as age, sex, the presence of DM, mean PHQ-9 score, mean GAD-7 score, METs, physical activity category, BMI before the pandemic, and dietary compliance during the pandemic were compared between the three groups that were weight-neutral, that lost weight, and that gained weight, BMI before the pandemic was significantly higher in the group that lost weight compared with the group that gained weight. METs were highest in the group that lost weight compared with the weight-neutral group and weight-gain group. The healthy nutrition coefficient was highest in the group that lost weight, followed by patients that were weight neutral and patients who gained weight. Dietary compliance was highest in the group that lost weight (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the patients according to weight change.

Table 3.

Differences between the patients that were weight neutral, that lost weight, and that gained weight

| Weight neutral | Weight loss | Weight gain | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ± SD, years | 48.2±10.8 | 44.2±12.4 | 44.7±13.4 | 0.19 |

| W/M, n | 44/9 | 111/23 | 189/38 | 0.99 |

| BMI ± SD, kg/m2 (before pandemic) | 35.1±8.9 | 38.1±8.2 | 36.6±7.5 | 0.01 |

| DM, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (36.5) | 53 (39.6) | 96 (42.3) | 0.71 |

| No | 33 (63.5) | 81 (60.4) | 131 (57.7) | |

| PHQ-9 score ± SD | 7.5±5.5 | 7.2±5.8 | 8.0±5.9 | 0.38 |

| GAD-7 score ± SD | 5.8±5.4 | 5.7±5.0 | 5.5±4.2 | 0.89 |

| IPAQ (Mets) ± SD | 1,014.1±1,350.7 | 761.1±1,231.9 | 436.0±979.5 | 0.001 |

| MET category, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 29 (9.6) | 86 (28.6) | 186 (61.8) | |

| Moderate | 19 (22.6) | 34 (40.5) | 31 (36.9) | 0.0001 |

| High | 6 (18.2) | 15 (45.5) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Meal frequency during pandemic ± SD | 3.3±1.6 | 3.8±2.0 | 4.0±1.7 | 0.386 |

| Healthy nutrition coefficient during pandemic ± SD | 38.8±6.1 | 39.6±5.7 | 37.2±6.7 | 0.007 |

| Dietary compliance, n (%) | ||||

| None | 13 (10.7) | 21 (17.2) | 88 (72.1) | |

| Rarely | 14 (16.3) | 18 (20.9) | 54 (62.8) | |

| Sometimes | 19 (16.7) | 39 (34.2) | 56 (49.1) | <0.0001 |

| Frequently | 5 (7.8) | 36 (56.3) | 23 (35.9) | |

| Almost always | 1 (5) | 16 (18.0) | 3 (15) |

SD, standard deviation; W/M, women/men; DM, diabetes mellitus; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MET, metabolic equivalent; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder.

Weight change was also calculated as the percentage weight change by subtracting the weight before the pandemic from the weight during the pandemic and dividing by the weight before the pandemic. Correlation analysis was then performed with the weight change and age, education status, METs category, dietary compliance, number of meals, and the healthy nutrition coefficient. Of these, only the healthy nutrition coefficient and METs categories were correlated with percentage weight loss. Percent weight change was related to METs categories, where patients in the moderately active and very active groups lost weight more compared with the least active groups. In the logistic regression analysis where both the healthy nutrition coefficient and METs categories were included as independent variables and the percentage weight change as the dependent variable, weight change was correlated negatively with the healthy nutrition coefficient and METs categories (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate LR analysis of prediction of % weight loss

| Univariate LR |

Multivariate LR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 0.996 (0.980–1.011) | 0.58 | ||

| Male | 0.978 (0.583–1.641) | 0.93 | ||

| Education status | 0.584 (0.299–1.039) | 0.23 | ||

| BMI | 0.983 (0.958–1.008) | 0.17 | ||

| Meals, n | 1.097 (0.978–1.231) | 0.12 | ||

| Healthy nutrition coefficient | 0.872 (0.812–0.937) | <0.001 | 0.884 (0.821–0.951) | 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 score | 1.403 (0.905–2.175) | 0.32 | ||

| GAD-7 score | 1.147 (0.696–1.890) | 0.59 | ||

| MET category | 4.698 (2.147–10.281) | |||

| 1 versus 2 | 0.318 (0.192–0.528) | <0.001 | 0.408 (0.222–0.748) | 0.004 |

| 1 versus 3 | 0.321 (0.152–0.679) | 0.003 | ||

| Presence of DM | 0.850 (0.571–1.265) | 0.42 | ||

OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder; MET, metabolic equivalent; DM, diabetes mellitus.

When the patients who had bariatric surgery were compared with the patients that were treated by other treatment modalities, there were lower percentage of patients who lost weight and also higher percentage of patients who gained weight in the bariatric surgery group compared with the other group (Table 5). The meal frequency during the pandemic was increased, dietary compliance and the healthy nutrition coefficient seemed to be higher in the bariatric surgery group compared with patients in the other group. In terms of physical activity, a greater percentage of patients were in the more active group in the bariatric surgery group compared with the other group. There were more patients with DM in the group treated with other modalities compared with the bariatric surgery group. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 categories according to a cut-off of 10 were similar between the two groups.

Table 5.

Differences between the patients that had been treated with bariatric surgery and other treatment modalities

| Bariatric surgery (n = 104) | Other treatment modalities (n = 318) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss status, n (%) | |||

| Weight loss | 43 (41.3) | 193 (60.7) | |

| Weight neutral | 21 (20.2) | 32 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Weight gain | 40 (38.5) | 93 (29.2) | |

| Meal frequency during pandemic | 4.8±2.4 | 3.6±1.5 | <0.001 |

| Healthy nutrition coefficient | 39.3±5.6 | 37.8±6.6 | <0.001 |

| Dietary compliance, n (%) | |||

| None | 21 (20.2) | 107 (33.6) | |

| Rarely | 15 (14.5) | 75 (23.6) | |

| Sometimes | 33 (31.7) | 85 (26.7) | <0.001 |

| Frequently | 23 (22.1) | 41 (12.9) | |

| Almost always | 12 (11.5) | 10 (3.2) | |

| MET category, n (%) | |||

| Low | 54 (51.9) | 250 (78.6) | |

| Moderate | 34 (32.7) | 50 (15.7) | <0.001 |

| High | 16 (15.4) | 18 (5.7) | |

| PHQ-9 category, n (%) | |||

| <10 | 72 (69.2) | 228 (71.7) | 0.62 |

| ≥10 | 32 (30.8) | 90 (28.3) | |

| GAD-7 category, n (%) | |||

| <10 | 79 (76.0) | 260 (81.8) | 0.19 |

| ≥10 | 25 (24.0) | 58 (18.2) | |

| DM | |||

| Yes | 23 (22.1) | 151 (47.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 81 (77.9) | 167 (52.5) |

MET, metabolic equivalent; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Regarding the patients with DM, the frequency of DM type, the therapy the patients received, change in insulin dose, difficulty in reaching medication during the pandemic, frequency of quitting or decreasing doses of medications during the pandemic, and HbA1c levels are shown in Table 6. In terms of complications, 22 (13.2%) had retinopathy, 88 (52%) had neuropathy, and 22 (13.2%) had nephropathy. The frequency of capillary glucose measurements and acute diabetic complications are also shown in Table 6. Of all patients with DM, 53 (31.5%) lost weight, 19 (11.3%) were weight neutral, and 96 (57.1%) gained weight. Among patients with DM, 133 (78.2%) had mild physical activity, 32 (18.2%) had moderate physical activity, and 5 (2.9%) had significant physical activity. Dietary compliance was good only in 30 (17.9%) patients with diabetes. Only 45 (26.5%) had PHQ-9 scores ≥10, and only 31 (18.2%) had GAD-7 scores ≥10. When patients with and without DM were compared in terms of dietary compliance, METs category, weight loss status, PHQ-9 category (with cut-off 10), and GAD-7 category (with cut-off 10), only patients without diabetes seemed to be more active; 29 (11.7%) patients in the nondiabetic group were in the very active group compared with 5 (2.9%) in the diabetic group.

Table 6.

Status of patients with DM (n = 170)

| Type of DM, n (%) | ||

| Type 1 | 5 (3.0) | |

| Type 2 | 132 (79.5) | |

| Unknown | 29 (17.5) | |

| DM therapy, n (%) | ||

| Tablet | 106 (67.1) | |

| Insulin | 21 (13.3) | |

| Tablet + Insulin | 31 (19.6) | |

| Change in insulin dose during pandemic, n (%) | ||

| No | 49 (76.6) | |

| Increase | 8 (12.5) | |

| Decrease | 7 (10.9) | |

| Quit or decreased dose of meds during pandemic, n (%) | ||

| No | 139 (84.8) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 17 (10.4) | |

| Yes, mostly | 7 (4.3) | |

| Yes, always | 1(0.6) | |

| HbA1c, % ±SD | 6.5±1.4 | |

| Frequency of capillary glucose measurement during pandemic, n (%) | ||

| No, not know how to | 25 (15.1) | |

| No, no tool | 39 (23.5) | |

| Some days, once a day | 56 (33.7) | |

| Some days, 2–3 times/day | 23 (13.9) | |

| Every day, 1–2 times/day | 13 (7.8) | |

| Every day; >3 times/day | 10 (6) | |

| Hypoglycemia during pandemic, n (%) | ||

| No, never | 104 (68.4) | |

| Yes, rarely | 22 (14.5) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 24 (15.8) | |

| Yes, frequently | 1 (0.7) | |

| Yes, always | 1 (0.7) | |

| FBG, mg/dL, n (%) | ||

| <100 | 12 (8.4) | |

| 101–160 | 73 (51.4) | |

| >160 | 25 (17.6) | |

| PPBG, mg/dL, n (%) | ||

| <160 | 36 (25.2) | |

| 161–220 | 50 (35.0) | |

| >220 | 16 (11.2) | |

DM, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; FBG, fasting blood glucose; PPBG, postprandial blood glucose.

Discussion

Lockdown periods have generally been associated with difficulties in maintaining weight. Our findings reveal that more than half of our population with obesity gained weight, and one-third lost weight during the pandemic. This is in line with previous studies; in Spain, 52% of a population with obesity gained weight [21] and in patients with obesity awaiting bariatric surgery, a small but significant increase in BMI was observed [27]. In a bariatric population with obesity, no significant changes in weight and BMI were observed, but a change in obesity class was reported in 17.8% of cases (10/56) [28].

A prominent change in eating habits was observed. It was evident in our findings that the number of meals per day had increased compared with before the pandemic. The content of what the participants ate changed with an increased frequency of bakery, packaged food, sweets, and vegetable consumption. These findings are in line with other groups who also found decreased consumption of vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, some fruits, nuts, seeds, cereal bread, and tubers and dairy products [29]. Fruits and vegetables (60.2%, each), herbal tea (37%), nuts (34.3%), and sweets (32.6%) consumption were increased in another cohort along with increased food intake in 31.8% of patients [30]. There has been a detectable shift toward carbohydrate-containing food such as confectionaries and bread [9, 10, 31]. Increased food intake [6, 9, 10], irregular and unhealthy eating patterns, and frequent snacking have been observed in many populations [4, 6, 9, 10, 20, 32, 33]. On the other hand, changes towards healthier diet patterns were also observed [7].

Physical activity is an important contributor to maintaining weight balance. In the lockdown, most of our participants had low physical activity. Moreover, patients in the group that gained weight were less physically active compared with the patients who lost weight. One of the most important factors affecting weight status seemed to be the physical activity status in our patient group. Periods of quarantine have been shown to have negative effects on the general physical activity status of people [34]. It has not been possible for people to maintain their physical activity status only through activities at home [35]. Besides having a lack of opportunities for outdoor and indoor sports activities [36], another influencing factor has been the lack of motivation for doing sports [35]. In an American cohort with obesity, about one-half reported a decreased amount of time for exercise and a decrease in the intensity of exercise during lockdown [20]. Decreased physical activity was observed in about one-third of the cohort in the United Arab Emirates [30], and about 60% of adults in Zimbabwe [29].

Confinement itself also results in mood and anxiety disorders. Our results revealed that only 28.4% of our patients had possible depression according to the PHQ-9 scale and only 19.0% had anxiety according to the GAD-7 score. The mean PHQ-9 score was 7.7 ± 5.9 and the mean GAD-7 score was 5.6 ± 5.1. Moreover, PHQ-7 and GAD-9 scores were not related to percent weight loss in our population. Feelings of loneliness, depression, and anxiety due to lockdown have been reported previously [10]. In an obese population on the waiting list for bariatric surgery in Italy, reduced anxiety scores were observed, possibly related to decreases in social interactions with others. Moreover, there was no change in the depression scores (SDS Depression index scores) in this population [28]. This was in contrast to other populations with obesity [20]. Depression and anxiety have previously been widely evaluated using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scoring systems in many populations. There seem to be some heterogeneous results, depending on the population studied. In a bariatric surgery population including 179 patients, the baseline PHQ-9 score was 6.2, similar to our results [37]. By contrast, the mean PHQ-9 scores were 2.30 ± 0.17 for Korean women with obesity [38], 4.4 ± 4.0 for a bariatric surgery population from Germany [39], and 13.8 ± 3.1 among 409 participants with obesity in the RAINBOW Randomized Clinical Trial [40]. GAD-7 score was evaluated in two studies from Germany, where the mean scores were around 3.6 in both populations with obesity [37, 39], quite similar to our results. On the other hand, higher levels were observed in women (9.7 ± 5.8) and men (7.1 ± 5.3) with obesity in another German population [41].

In our group, about 20% of our patients had problems attaining their medications, 40% had problems reaching their physicians, and about 65% had problems reaching hospitals for their laboratory tests. For an adult population in Zimbabwe, for around 60%, medications and a similar percentage of physician appointments were not easily available [29].

The level of concern about contracting COVID-19 was increased in only 24.8% of our population. This was in contrast to a group with obesity from Spain that reported concern in about 70% of the participants [42].

Higher percentage of patients gained weight and lower percentage of patients lost weight in the bariatric surgery group compared with the patients treated with other treatment modalities. Although their dietary compliance was higher and the healthy nutrition coefficient seemed to have increased, their meal frequencies were somewhat higher. Moreover, they seemed to be less physically active in relation to the patients who had been treated with other treatment modalities. The frequency of depression and anxiety scores were low in our total population and were similar within the groups treated by surgery and other treatment modalities. The findings regarding the patients with a history of bariatric surgery were similar to a report by Andreu et al. [43] who investigated the effect of the pandemic in a group of patients who had undergone bariatric surgery. The pandemic affected the dietary habits of 72% of participants, and 83.5% of them had become more sedentary. Moreover, 27% and 36% seemed to have depression and anxiety [43]. In a Portuguese population who had bariatric surgery before the pandemic, consumption of energy-dense foods was increased and this was associated with lack of expected decrease in BMI of the patients. Moreover, moderate-to-severe anxiety and depression scores were found to be associated with eating energy-dense foods [44]. On the contrary, there seemed to be no difference in terms of target weight loss in 1 year in patients who had undergone bariatric surgery at different time periods before the pandemic in another group of individuals with obesity. There was only a decrease in exercise capacity among those who had surgery just before the pandemic [45].

Participants who had diabetes as a complication were analyzed separately. The weight status was comparable to the nondiabetic patients in the study. Most of the patients with diabetes had low activity levels. The percentage of those that were active was significantly lower than those who did not have diabetes. About one-fifth of patients with DM had depression and anxiety. This did not seem to be related to their eating patterns. Having diabetes in the overall population with obesity did not seem to have an impact on the weight gain status. Mostly, patients did not change their medications. Those using insulin mostly did not change their insulin dose. More than one-third of the patients either did not know how to measure their capillary glucose levels or did not have a tool to measure them. Only 1.83% measured their blood glucose levels every day.

According to these rare measurements, fasting blood glucose was >160 mg/dL in 17.6% of patients and the postprandial level was >220 mg/dL in 2%. Previous data from the Netherlands revealed that despite weight gain and having less intense exercise, glycemic control did not deteriorate in a population with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Also, an increase in perceived stress and anxiety was observed [21]. A Turkish group also looked into the weight gain and glycemic control in 101 patients with type 2 DM, and they found no statistically significant change in weight, blood glucose levels, and HbA1c. The frequency of blood glucose testing was also low, as in our population [46]. No difference in blood glucose control [47], worsening of control in one-quarter of the previously controlled patients [48], and even improved glycemic control were observed [49] in different populations. Our results are unique in terms of examining the status of patients with diabetes separately.

There are several limitations to our study. Because of the online nature of the survey, the eating habits, exercise habits, and weight changes were all self-reported by the patients; they depended on the patients' perceptions and thus were subject to reporting bias. Due to the lockdown and the continuation of the pandemic, face-to-face interviews were not possible. Moreover, due to the length of the survey, we were not able to ask about all determinants of eating behavior and weight gain. Blood glucose measurements relied on the patient's conducting fingerstick tests, which were performed occasionally.

Conclusion

The quarantine period during the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in changes in eating and exercise habits and caused an increase in weight in about one-half of the population with obesity. Decreased exercise habits and having unhealthy eating behaviors, in particular, resulted in weight gain. There were also depression and anxiety in some of our patients, but these did not seem to be related to eating, exercise habits, and weight status. In patients with diabetes, weight gain was not different compared with the nondiabetic population with obesity, but considering physical activity, the nondiabetic patients were more physically active in the whole cohort. Blood glucose concentrations were within target in most of the patients.

Overall, 2 months is a relatively short time for major changes in weight status and metabolic control and thus to cause a change in the course of chronic diseases such as obesity and DM. The effects of changes in eating and exercise habits would lead to more important problems when persisting over longer periods. Metabolic and cardiovascular complications are likely to emerge, possibly after longer periods of restrictions. It would be interesting to see the extended effect of the changes in unhealthy lifestyle habits with this population, which we are planning to evaluate. It may be like a legacy effect extending to a longer period. Thus, measures to encourage exercise programs at home and, when possible, outside, without going to confined places such as gyms, can be established for confinement periods. It is also evident that some other measures have to be taken for patients to reach healthcare services or for them to obtain advice about the management of their disease, which includes lifestyle measures. For this, telemedicine would be an effective tool. Alternative solutions for motivation of maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors may be through certain online applications or education and encouragement through social media. In conclusion, strong policies could be determined to establish a suitable and controlled telehealthcare program that would serve the people with chronic diseases during lockdown periods.

Statement of Ethics

This research complies with the guidelines for human studies and was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participating in the study. The study was approved by the Local Institutional Board at Koç University, Istanbul (approval number: 2020.268.IRB1.091).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

There is no funding for the study.

Author Contributions

Dilek Yazıcı: planning of the project, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Feray Akbaş, Sinem Kıyıcı, Taner Bayraktaroğlu, and Volkan Yumuk: data collection and preparation of the manuscript. Havva Sezer: data analysis and data collection. Hande Bulut: data analysis. The rest: data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author if needed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Arzu Baygül from Koç University Medical School, Biostatistics Department, for her contributions.

References

- 1.Castañeda-Babarro A, Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Gutiérrez-Santamaría B, Coca A. Physical activity change during COVID-19 confinement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 21;17((18)):6878. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin F, Song Y, Nassis GP, Zhao L, Dong Y, Zhao C, et al. Physical activity, screen time, and emotional well-being during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jul 17;17((14)):5170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez-de-Quel Ó, Suárez-Iglesias D, López-Flores M, Pérez CA. Physical activity, dietary habits and sleep quality before and during COVID-19 lockdown: a longitudinal study. Appetite. 2021 Mar 1;158:105019. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020 May 28;12((6)):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bracale R, Vaccaro CM. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 Aug;30((9)):1423–6. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, Attinà A, Cinelli G, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020 Jun 8;18((1)):229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Pérez C, Molina-Montes E, Verardo V, Artacho R, García-Villanova B, Guerra-Hernández EJ, et al. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients. 2020;12((6)):1730. doi: 10.3390/nu12061730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Roso MB, de Carvalho Padilha P, Mantilla-Escalante DC, Ulloa N, Brun P, Acevedo-Correa D, et al. Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent's dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients. 2020;12((6)):1807. doi: 10.3390/nu12061807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarmozzino F, Visioli F. Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown modified dietary habits of almost half the population in an Italian sample. Foods. 2020;9((5)):675. doi: 10.3390/foods9050675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidor A, Rzymski P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: experience from Poland. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 3;12((6)):1657. doi: 10.3390/nu12061657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao A, Li Z, Ke Y, Huo S, Ma Y, Zhang Y, et al. Dietary diversity among Chinese residents during the COVID-19 outbreak and its associated factors. Nutrients. 2020;12((6)):1699. doi: 10.3390/nu12061699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson E, Boyland E, Chisholm A, Harrold J, Maloney NG, Marty L, et al. Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: a study of UK adults. Appetite. 2021 Jan 1;156:104853. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, Costa S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res. 2020;29((4)):e13074–e74. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36((4)):e00054020. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, O'Conor RM, Curtis L, Benavente JY, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173((2)):100–9. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Cocchi C, Maffei S, Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 Aug 28;30((9)):1409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chua JL, Touyz S, Hill AJ. Negative mood-induced overeating in obese binge eaters: an experimental study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Apr;28((4)):606–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardi V, Leppanen J, Treasure J. The effects of negative and positive mood induction on eating behaviour: a meta-analysis of laboratory studies in the healthy population and eating and weight disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015 Oct;57:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusuma D, Pradeepa R, Khawaja KI, Hasan M, Siddiqui S, Mahmood S, et al. Low uptake of COVID-19 prevention behaviours and high socioeconomic impact of lockdown measures in South Asia: evidence from a large-scale multi-country surveillance programme. SSM Popul Health. 2021 Mar;13:100751. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almandoz JP, Xie L, Schellinger JN, Mathew MS, Gazda C, Ofori A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on weight-related behaviours among patients with obesity. Clin Obes. 2020 Oct;10((5)):e12386. doi: 10.1111/cob.12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruissen MM, Regeer H, Landstra CP, Schroijen M, Jazet I, Nijhoff MF, et al. Increased stress, weight gain and less exercise in relation to glycemic control in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021 Jan;9((1)):e002035. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Aug;35((8)):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16((9)):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sari YE, Kokoglu B, Balcioglu H, Bilge U, Colak E, Unluoglu I. Turkish reliability of the patient health questionnaire-9. Biomed Res. 2016:S460–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konkan R, Şenormancı Ö, Güçlü O, Aydin E, Sungur MZ. Validity and reliability study for the Turkish adaptation of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale. Arch Neuropsychiatr. 2013;50:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May 22;166((10)):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beisani M, Vilallonga R, Petrola C, Acosta A, Casimiro Pérez JA, García Ruiz de Gordejuela A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on a bariatric surgery waiting list cohort and its influence in surgical risk perception. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021 Mar;406((2)):393–400. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-02040-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert U, Losurdo P, Leschiutta A, Macchi S, Samardzic N, Casaganda B, et al. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown on body weight, maladaptive eating habits, anxiety, and depression in a bariatric surgery waiting list cohort. Obes Surg. 2021 May;31((5)):1905–11. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsungo TM, Chopera P. Effect of the COVID-19-induced lockdown on nutrition, health and lifestyle patterns among adults in Zimbabwe. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2020 Dec;3((2)):205–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radwan H, Al Kitbi M, Hasan H, Al Hilali M, Abbas N, Hamadeh R, et al. Indirect health effects of COVID-19: unhealthy lifestyle behaviors during the lockdown in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 18;18((4)):1964. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber BC, Steffen J, Schlichtiger J, Brunner S. Altered nutrition behavior during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in young adults. Eur J Nutr. 2021 Aug;60((5)):2593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scully M, Dixon H, Wakefield M. Association between commercial television exposure and fast-food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009 Jan;12((1)):105–10. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruíz-Roso MB, de Carvalho Padilha P, Matilla-Escalante DC, Brun P, Ulloa N, Acevedo-Correa D, et al. Changes of physical activity and ultra-processed food consumption in adolescents from different countries during Covid-19 pandemic: an observational study. Nutrients. 2020;12((8)):2289. doi: 10.3390/nu12082289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Oliveira Neto L, Elsangedy HM, Tavares VDO, Teixeira CVS, Behm DG, Silva-Grigoletto ME. #TrainingInHome: training at home during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: physical exercise and behavior-based approach. Braz J Exerc Physiol. 2020;19:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfawaz H, Amer OE, Aljumah AA, Aldisi DA, Enani MA, Aljohani NJ, et al. Effects of home quarantine during COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity and dietary habits of adults in Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep. 2021 Mar 15;11((1)):5904. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippi G, Henry BM, Sanchis-Gomar F. Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020 Jun;27((9)):906–8. doi: 10.1177/2047487320916823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hilgendorf W, Butler A, Timsina L, Choi J, Banerjee A, Selzer D, et al. A behavioral rating system predicts weight loss and quality of life after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Aug;14((8)):1167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung FU, Luck-Sikorski C. Overweight and lonely? A representative study on loneliness in obese people and its determinants. Obes Facts. 2019;12((4)):440–7. doi: 10.1159/000500095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Köhler H, Dorozhkina R, Gruner-Labitzke K, de Zwaan M. Specific health knowledge and health literacy of patients before and after bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study. Obes Facts. 2020;13((2)):166–78. doi: 10.1159/000505837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma J, Rosas LG, Lv N, Xiao L, Snowden MB, Venditti EM, et al. Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5;321((9)):869–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wölk E, Stengel A, Schaper SJ, Rose M, Hofmann T. Neurotensin and Xenin show positive correlations with perceived stress, anxiety, depressiveness and eating disorder symptoms in female obese patients. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15:629729. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.629729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jimenez A, de Hollanda A, Palou E, Ortega E, Andreu A, Molero J, et al. Psychosocial, lifestyle, and body weight impact of COVID-19-related lockdown in a sample of participants with current or past history of obesity in Spain. Obes Surg. 2021 May;31((5)):2115–24. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreu A, Flores L, Molero J, Mestre C, Obach A, Torres F, et al. Patients undergoing bariatric surgery: a special risk group for lifestyle, emotional and behavioral adaptations during the COVID-19 lockdown. Lessons from the first wave. Obes Surg. 2022 Feb;32((2)):441–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05792-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durão C, Vaz C, de Oliveira VN, Calhau C. Confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic after metabolic and bariatric surgery-associations between emotional distress, energy-dense foods, and body mass index. Obes Surg. 2021 Oct;31((10)):4452–60. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira X, Romero-Velez G, Skendelas JP, Rodriguez-Quintero JH, Grosser R, Lima DL, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect target weight loss 1 year post bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2021 Nov;31((11)):4926–32. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05672-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Önmez A, Gamsızkan Z, Özdemir Ş, Kesikbaş E, Gökosmanoğlu F, Torun S, et al. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Turkey. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Nov–Dec;14((6)):1963–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D'Onofrio L, Pieralice S, Maddaloni E, Mignogna C, Sterpetti S, Coraggio L, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on glycaemic control in subjects with type 2 diabetes: the glycalock study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021 Jul;23((7)):1624–30. doi: 10.1111/dom.14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biancalana E, Parolini F, Mengozzi A, Solini A. Short-term impact of COVID-19 lockdown on metabolic control of patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes: a single-centre observational study. Acta Diabetol. 2021 Apr;58((4)):431–6. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rastogi A, Hiteshi P, Bhansali A. Improved glycemic control amongst people with long-standing diabetes during COVID-19 lockdown: a prospective, observational, nested cohort study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2020 Oct 21;:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s13410-020-00880-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author if needed.