Abstract

An endonuclease IV homolog was identified as the product of a conceptual open reading frame in the genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. The T. maritima endonuclease IV gene encodes a 287-amino-acid protein with 32% sequence identity to Escherichia coli endonuclease IV. The gene was cloned, and the expressed protein was purified and shown to have enzymatic activities that are characteristic of the endonuclease IV family of DNA repair enzymes, including apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease activity and repair activities on 3′-phosphates, 3′-phosphoglycolates, and 3′-trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphates. The T. maritima enzyme exhibits enzyme activity at both low and high temperatures. Circular dichroism spectroscopy indicates that T. maritima endonuclease IV has secondary structure similar to that of E. coli endonuclease IV and that the T. maritima endonuclease IV structure is more stable than E. coli endonuclease IV by almost 20°C, beginning to rapidly denature only at temperatures approaching 90°C. The presence of this enzyme, which is part of the DNA base excision repair pathway, suggests that thermophiles use a mechanism similar to that used by mesophiles to deal with the large number of abasic sites that arise in their chromosomes due to the increased rates of DNA damage at elevated temperatures.

The most common lesion in DNA is the apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site. AP sites are generated by the action of DNA glycosylases which remove modified and mismatched bases from damaged DNA (7, 23). AP sites can also arise spontaneously via depurination and depyrimidination (28) and through the direct interaction of DNA with reactive oxygen species (19). These sites are noninstructive to DNA polymerases and can be mutagenic or genotoxic if left unrepaired (31). The repair of the AP site is initiated by a class of enzymes referred to as AP endonucleases (12). AP endonucleases hydrolytically cleave the phosphodiester bond 5′ to an AP site to generate a 3′-hydroxyl group and a 5′-terminal sugar phosphate (3, 25). A deoxyribophosphodiesterase can remove the 5′-terminal sugar phosphate, leaving a single nucleotide gap which is then fully repaired by a DNA polymerase and DNA ligase, restoring the genetic information (11, 13).

There are two families of AP endonucleases represented by the Escherichia coli enzymes exonuclease III and endonuclease IV (4, 10, 35). Exonuclease III is the major AP endonuclease of E. coli, responsible for approximately 90% of the activity measured in crude extracts (29, 44). Endonuclease IV is generally a minor AP endonuclease, but it is induced by the presence of superoxide anion radicals to levels comparable to those of exonuclease III (5).

In addition to AP endonuclease activity, exonuclease III and endonuclease IV have other activities in common for the repair of oxidative DNA damage. Reactive oxygen species (hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical) generated by ionizing radiation and normal aerobic metabolism induce the formation of strand breaks in DNA (16). These strand breaks contain 3′-blocking groups such as phosphates and phosphoglycolates which inhibit DNA replication (8, 17, 19). Endonuclease IV and exonuclease III have both phosphomonoesterase and phosphodiesterase activities which catalyze the removal of 3′-phosphates and 3′-phosphoglycolates at strand breaks (8, 17, 24, 42).

Several glycosylases have an associated AP-lyase activity (7). Perhaps the most extensively studied glycosylase is E. coli endonuclease III (43). Endonuclease III cleaves the 3′ side of AP sites through a β-elimination mechanism, generating a trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate (33). This is an additional 3′-blocking group that is removed by both exonuclease III and endonuclease IV (25, 45).

Exonuclease III homologs have been identified in eukaryotes including Drosophila (Rrp1), Arabidopsis (Arp), and humans (Ape) (4, 10). Similarly to exonuclease III of E. coli, Ape is the major AP endonuclease of humans (9). The endonuclease IV family of AP endonucleases currently consists of two functional members, E. coli endonuclease IV and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apn1 (35). In contrast to E. coli endonuclease IV, Apn1 of yeast is the major AP endonuclease of that organism (20). Searches for endonuclease IV homologs in other eukaryotes including Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Caenorhabditis elegans led to the discovery of cDNA sequences whose open reading frames (ORFs) predict protein sequences that have high similarity to sequences of both endonuclease IV and Apn1 (32, 36). Although S. pombe possesses a gene which could encode an endonuclease IV homolog, SpApn1, it is apparently not expressed, and no AP endonuclease activity has been detected in S. pombe extracts (36). An endonuclease IV homolog (CeApn1) has been identified in C. elegans; however, a recombinant gene does not express a functional protein in E. coli, and the activities of this homolog have not been characterized (32).

DNA repair mechanisms are best understood for mesophilic organisms, whereas DNA repair in hyperthermophiles remains for the most part enigmatic (15). Since the rate of decomposition of DNA is accelerated at high temperatures (26, 27), hyperthermophiles may have more efficient mechanisms for maintaining their genomic integrity. The finding that DNA glycosylase activities exist in hyperthermophiles suggests that base excision repair could play a major role in repairing damaged DNA (22, 34). Until now, no thermophilic AP endonuclease of a base excision repair system has been characterized.

Microbial genome sequencing projects have facilitated the identification of homologous genes for a number of conserved proteins. Many of the microorganisms whose genomes have been sequenced are thermophilic members of the domain Bacteria or Archaea. We mined the sequence databases to identify potential AP endonucleases of hyperthermophiles. The Gapped BLAST (1) program was used to identify nucleotide sequence fragments of the Thermotoga maritima genome whose tentative translation showed sequence similarity to E. coli endonuclease IV. The gene fragments were assembled to encode an ORF homologous to endonuclease IV. The gene was cloned, and a protein was expressed. The expressed protein was purified and assayed for activities that are characteristic of both endonuclease IV and Apn1, AP endonuclease activity, and 3′-repair activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Strain BW565 [HfrC Δ(cir-nfo)542 (Tetr) metB1 uhp-1 pyrE41 relA1 tonA22 T2r (ompF627) spoT1] was a gift from Bernard Weiss (Department of Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Ga.). This strain was lysogenized with λDE3, using a λDE3 lysogenization kit from Novagen Inc. Expression vectors pET24a and pET28a were obtained from Novagen. Plasmid pET24-Eco Nfo contains the E. coli endonuclease IV gene cloned into the NdeI and HindIII sites of vector pET24a.

Cloning of the T. maritima endonuclease IV gene.

Preliminary sequence data were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research website (20a). PCR primers were designed to amplify the core sequence of the T. maritima endonuclease IV gene. The forward primer (5′ GGGGTAAGACATATGATAAAAATAGGAGCTC 3′) and reverse primer (5′ GGCCGGAAGCTTTTACTCTATACCGAATTTTTCTATGATCTC 3′) contained NdeI and HindIII flanking restriction sites for the directional cloning into a compatible expression vector. The reverse primer engineered a stop codon at position 286 of the ORF. Template nucleic acid was prepared via phenol-chloroform extraction of whole cells of T. maritima MSB8. The PCRs were done in a total volume of 100 μl containing approximately 1.5 μM primers, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μl of the template nucleic acid, and 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) with the supplied buffer at a 1× concentration. The reaction mixture was incubated at 95°C for 15 min. The following PCR cycle was repeated 35 times: denaturation at 95°C for 40 s, annealing of primers at 55°C for 40 s, and synthesis at 72°C for 1 min. This was followed by a 10-min incubation at 72°C before the mixture was returned to room temperature. The PCR-amplified gene was digested with the restriction enzymes NdeI and HindIII and cloned into the compatible sites of the expression vector pET28a, creating plasmid pET28-Tma Nfo. Cloning the gene into the NdeI and HindIII sites of pET28a places a His tag sequence on the N terminus of the expressed protein. The expected insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Enzyme purification. (i) Purification of T. maritima endonuclease IV.

E. coli BW565(DE3) was transformed with plasmid pET28-Tma Nfo via a method involving one-step preparation and transformation of competent cells (2). A transformant was grown in 24 liters of LB medium (37) containing 0.1 mM ZnSO4, 0.1 mM MnCl2, and 34 μg of kanamycin per ml at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.8. Expression of T. maritima endonuclease IV was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to 1 mM. Induction proceeded for 5 h at 30°C. The cells (50 g) were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 100 ml of buffer A (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.6], 10 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl). A cell extract was prepared by sonication with a cell disruptor (Heat Systems-Ultrasonics, Inc.) at maximum power with a standard probe. The sonicate was clarified by centrifugation and filtration through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter (fraction I). Fraction I (250 ml × 5.8 mg/ml) was applied at 4 ml/min to a 5-ml HiTrap chelating column (Pharmacia) charged with Ni2+, and the column was washed with 30 ml of buffer B (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.6], 10 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl). The His-tagged protein was then eluted with 15 ml of buffer B containing an imidazole concentration of 500 mM. The eluted protein was immediately diluted to a final volume of 75 ml with buffer C (20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS]-NaOH [pH 8], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol [BME]) and then dialyzed against buffer C containing 200 mM NaCl (fraction II). Fraction II (75 ml × 1.5 mg/ml) was incubated at 65°C for 10 min, and precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation and filtration (fraction III). Fraction III (80 ml × 0.9 mg/ml) was applied to a 5-ml Q-Sepharose HiTrap column (Pharmacia), and T. maritima endonuclease IV was recovered from the flowthrough (fraction IV). Fraction IV (90 ml × 0.73 mg/ml) was applied to a 5-ml Heparin HiTrap column (Pharmacia) and eluted with buffer C containing 600 mM NaCl (fraction V). The enzyme purity was >95% as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and staining of the gel with Coomassie blue. Approximately 60 mg of T. maritima endonuclease IV was purified from 24 liters of cells.

(ii) Purification of E. coli endonuclease IV.

E. coli BW565(DE3) transformed with pET24-Eco Nfo was grown in LB medium (37) containing 0.1 mM ZnSO4 and 34 μg of kanamycin per ml at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.6. Expression of endonuclease IV was induced by the addition of IPTG to 1 mM. Induction proceeded for 4 to 6 h at 28°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at the end of the induction period and stored at −80°C. Thawed cells were suspended at 5 ml/g of cell paste in buffer C containing 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 8) and 400 mM NaCl. The cell extract was prepared via sonication and clarified by centrifugation (fraction I). To remove nucleic acids, fraction I was applied to a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow (Pharmacia) column (2.6 by 20 cm), and the proteins were eluted in the flowthrough. The eluent was dialyzed overnight in buffer C containing 50 mM NaCl (fraction II). Fraction II was applied to a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow column (2.6 by 40 cm). A 1-liter gradient was run at 15 ml/min to a final NaCl concentration of 500 mM. Fractions containing endonuclease IV were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and dialyzed overnight in buffer C containing 50 mM NaCl (fraction III). Fraction III was applied to two 5-ml Heparin HiTrap (Pharmacia) columns in series. A 150-ml gradient was run at 3 ml/min to a final NaCl concentration of 500 mM. Fractions containing endonuclease IV were identified by absorbance at 280 nm and verified by SDS-PAGE. The fractions were pooled (fraction IV), and the enzyme purity was >95% as determined by SDS-PAGE and staining of the gel with Coomassie blue.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy was performed with an Aviv 62DS spectropolarimeter. Proteins were diluted to 8 μM into a degassed buffer containing 1 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 8), 250 mM NaCl, and 1 mM BME. The protein samples were analyzed in quartz cuvettes with a 1-mm path length. To analyze the secondary structure of the proteins, spectra were recorded for every nanometer from 250 to 200 nm with a 1-nm bandwidth. After subtraction of the baseline from the spectra of the buffer alone, the mean residue elipticity was calculated (21). To analyze the thermostability of the proteins, the samples were incubated for 1.5 min at every degree from 25 to 95°C, and the spectrum was recorded at a wavelength of 222 nm with a 1-nm bandwidth and a 30-s averaging time for the data collection. The mean residue elipticity was calculated at each temperature (21).

Substrates and enzyme assays. (i) M13 DNA containing phosphate 3′-end groups.

A DNA substrate containing 33P-labeled 3′-phosphate groups was prepared as follows. An M13 replicative-form RF (M13RF) DNA labeled with [33P]dAMP was prepared as described previously (41), substituting 15 μCi of [α-33P]dUTP with 15 μCi of [α-33P]dATP. The lyophilized product M13RF DNA labeled with [33P]dAMP (specific activity, 60 cpm/fmol) was dissolved in 100 μl of H2O. To produce 3′-phosphate ends, 50 μl of the DNA (containing 1 μg of total DNA including 0.5 μg of labeled DNA) and 1.5 μg calf thymus DNA were incubated in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.05 U of micrococcal nuclease (Pharmacia) for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of 2 μl of 0.5 M Na2EDTA. After phenol-chloroform deproteination, the DNA was precipitated with ethanol, rinsed twice with 70% ethanol, lyophilized, and redissolved in 100 μl of H2O. The final specific activity (after dilution of 0.5 μg of the labeled DNA with 2 μg of unlabeled DNA) was 15 cpm/fmol. The percentage of DNA containing 3′-phosphate ends was estimated by determining the maximum percent release of product by reacting of 50,000 cpm of the labeled substrate in a reaction mixture (100 μl) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, and 1 U of calf alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) at 37°C for 30 min. Following the reaction, 110 μl of 10% trichloracetic acid, 10 μl of calf thymus DNA (2.5 mg/ml), and 30 μl of 5% Norit charcoal were added; following centrifugation, radioactivity contained in the supernatant was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. The maximum percent release of 3′-phosphate end groups was estimated to be 50% of the total counts per minute used per reaction. It was estimated that at 65°C, 25% of the substrate did not participate in the reaction due to melting, based on measurements of the release of the 3′-phosphate products at 37 and 65°C, using T. maritima endonuclease IV. The amount of substrate containing accessible 3′-phosphate ends at 65°C was determined as follows. The number of counts per minute used per reaction was multiplied by a factor of 0.375 (1 − 0.5 [fraction of 3′-phosphate ends containing DNA] × 0.75 [fraction of DNA resistant to melting at 65°C]). DNA 3′-phosphatase activity was assayed in a reaction measuring the release of 3′-phosphate groups from a M13mp18 double-stranded DNA substrate. A typical reaction mixture (100 μl) consisted of 1.2 pmol of 33P-labeled substrate containing 3′-phosphate ends, 20 ng of T. maritima endonuclease IV, 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8), and 100 mM NaCl and was incubated at 65°C for 15 min. Release of phosphate was determined by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid in the presence of Norit charcoal or by anion-exchange high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (38).

(ii) M13 double-stranded DNA containing 3′-incised AP sites.

An M13RF DNA substrate containing 33P-labeled AP sites was prepared essentially as described previously (14, 41). Deoxyribophosphodiesterase activity was assayed in a reaction measuring the release of trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate from a M13RF18 DNA substrate containing 3′-incised AP sites and by anion-exchange HPLC chromatography as described previously (38, 39).

(iii) Oligonucleotide substrate containing phosphoglycolate 3′-end groups.

The substrate was prepared by previously described methods (40, 42), with small modifications. [α-33P]dATP (2,000 Ci/mmol; Dupont) was used rather than [α-32P]dATP, and the step involving the reduction of aldehyde to alcohol with sodium borohydride was omitted. The release of 3′-phosphoglycolate from the oligonucleotide pd(T)20[33P]PGA was measured in a typical reaction mixture containing 12,000 to 20,000 cpm, 0.15 μg of pd(A)40–60, 20 ng of T. maritima endonuclease IV, 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), and 100 mM NaCl in a volume of 10 μl for 30 min at 65°C. The release of [33P]phosphoglycolate was determined by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid and Norit charcoal. Product analysis was accomplished by separation by anion-exchange HPLC as described previously (40).

(iv) T4-AP [3H]DNA.

T4-AP [3H]DNA was prepared as described previously (6), and reactions were performed with minor modifications. The enzyme dilution buffer contained 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME, and 1 μg of nuclease-free bovine serum albumin per ml. The reaction mixture (0.2 ml) contained 4.5 μM T4-AP [3H]DNA (5.7 × 103 cpm/nmol), 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME, 1 mM EDTA, and approximately 50 U of enzyme. One unit of enzyme released 1 pmol of acid-soluble nucleotide.

(v) Double-stranded oligonucleotide containing an AP site.

An oligonucleotide containing a single AP site was prepared as follows. A reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 1,000 pmol of a 19-mer oligonucleotide incorporating a single uracil (5′ GCAGCGCAGUCAGCCGACG 3′), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 70 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), and 25 ng of uracil glycosylase was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Following this reaction, 15 pmol of the resulting AP site-containing oligonucleotide was radioactively labeled at the 5′ end by a treatment with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP (New England Nuclear) for 1 h at 37°C. The oligonucleotide was purified away from unlabeled radioactive ATP and reaction components by applying the mixture to a G-25 desalting column (Pharmacia). The AP oligonucleotides were annealed to a threefold excess of a complementary oligonucleotide (5′ CGTCGGCTGACTGCGCTGC 3′) on ice for 2 h. AP endonuclease assays were performed in a total volume of 15 μl containing 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME, and 500 nM unlabeled and 10 nM 5′-32P-labeled AP site-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide. Reactions began at the time of enzyme addition (0.05 to 500 nM T. maritima endonuclease IV) and proceeded for 10 min at 65°C. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 15 μl of 2× formamide buffer and stored on ice. Half of the reaction contents were electrophoresed on a 20% denaturing acrylamide gel. The radioactivity of both the cleaved and uncleaved AP oligonucleotides were visualized and quantified on a betascope (Biogen). The Km values determined for T. maritima endonuclease IV with each of the above substrates were obtained from a Lineweaver-Burk plot.

RESULTS

Identification and cloning of the T. maritima endonuclease IV gene.

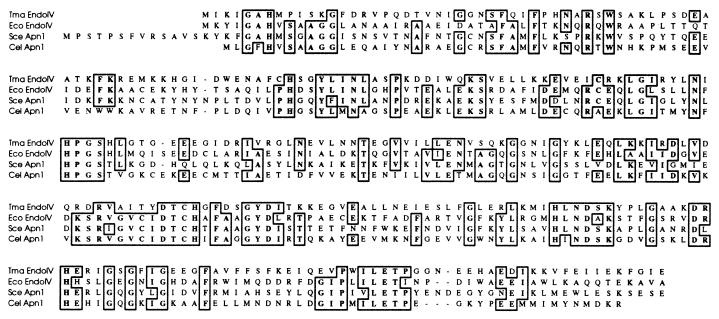

To identify a thermophilic version of endonuclease IV, Gapped BLAST (1) searches were performed against the T. maritima partial sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, using the E. coli endonuclease IV protein as the query sequence. We identified several sequence fragments which had conceptual ORF translations with regions of homology to the endonuclease IV query sequence, indicating that it is highly likely that an endonuclease IV homolog exists in the genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium T. maritima. By combining two sequence fragments (accession no. BTMCU60R and BTMBD54R), we identified a region encoding a 285-amino-acid protein which had 32, 32, and 30% amino acid sequence identity to E. coli endonuclease IV, S. cerevisiae Apn1, and C. elegans Apn1, respectively (Fig. 1). The protein was not terminated by a stop codon but contained an amino acid sequence corresponding to the entire E. coli endonuclease IV protein. This core sequence was amplified by PCR, and a stop codon at position 286 was added in the process. The PCR product was cloned into an expression vector, pET28a, which places a His tag sequence at the 5′ end of the gene. Later, TBLASTN searches using Gapped BLAST with the T. maritima endonuclease IV core sequence as the query sequence resulted in the identification of an overlapping sequence fragment which contained the very 3′ end of the gene (accession no. BTMAT45F). The complete ORF translation indicated that the full-length protein is only two residues longer than the core sequence described above.

FIG. 1.

Amino acid alignment of T. maritima endonuclease IV with homologs from E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and C. elegans. Amino acid sequences of T. maritima endonuclease IV (Tma EndoIV), E. coli endonuclease IV (Eco EndoIV; accession no. 2506194), S. cerevisiae Apn1 (Sce Apn1; accession no. 543825), and C. elegans Apn1 (Cel Apn1; accession no. 1353160) were aligned with the program CLUSTAL W (39).

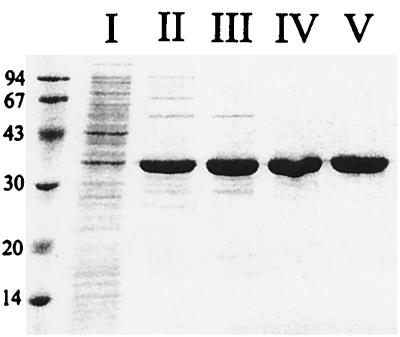

Purification of T. maritima endonuclease IV.

The gene was expressed under the direction of an IPTG-inducible T7 promoter, and the T. maritima endonuclease IV was purified as a His-tagged protein. An EDTA-resistant AP endonuclease activity, measured with the T4-AP [3H]DNA substrate, copurified with the expressed protein of ∼34 kDa (Fig. 2, lane V), consistent with the molecular weight based on the conceptual translation of the gene sequence. The purification procedure provided a 64% yield of the EDTA-resistant AP endonuclease activity in the crude extract. All enzyme assays were performed with the His-tagged protein which is truncated for the two C-terminal amino acids.

FIG. 2.

Purification of T. maritima endonuclease IV. Approximately 60 mg of pure T. maritima endonuclease IV was purified from ∼1.1 g of total protein. To evaluate the purity and estimate the molecular weight, 5 μg of total protein was electrophoresed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue. The lane labels correspond to each of the fractions detailed in Materials and Methods. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons.

Analysis of enzymatic activities.

The purified T. maritima endonuclease IV was assayed for the various activities that are characteristic of the endonuclease IV family. Since T. maritima is a hyperthermophile, growing at temperatures approaching 90°C, the recombinant proteins isolated from this organism are expected to be thermostable. Since many of the substrates used in the following enzyme assays are based on oligonucleotides, denaturation makes them unsuitable for use at very high temperatures. Therefore, the enzyme assays were arbitrarily restricted to 65°C.

T. maritima endonuclease IV was assayed for 3′-repair diesterase activity with two substrates. The enzymatic release of trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate was measured using a plasmid substrate containing AP sites incised by E. coli endonuclease III. After treatment of the substrate with T. maritima endonuclease IV, the reaction contents were subjected to anion-exchange HPLC to resolve the products of the reaction. The major peak of radioactivity eluted at a position corresponding to the sugar-phosphate product trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate. The apparent Km for the release of trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphate was 0.04 μM. To determine the effect of pH on the reaction, we performed the assay over a pH range of 6.0 to 9.5. The enzyme shows a broad pH optimum across the pH range tested (data not shown). To evaluate the release of phosphoglycolate from the 3′ ends of DNA, we incubated T. maritima endonuclease IV with the substrate pd(T)20[33P] PGA/pd(A)40–60 containing 3′-phosphoglycolate ends and resolved the products of the reaction by anion-exchange HPLC. The major peak of radioactivity eluted at a position corresponding to phosphoglycolate. The apparent Km for the release of phosphoglycolate was 0.09 μM.

To determine if T. maritima endonuclease IV has a phosphomonoesterase activity, we incubated the enzyme with a plasmid substrate containing 3′-33P-labeled phosphate ends. The reaction products were resolved by anion-exchange HPLC. The major peak of radioactivity eluted at a position corresponding to inorganic phosphate, demonstrating that T. maritima endonuclease IV possesses a phosphatase activity. The apparent Km for the release of phosphate was 0.10 μM. These results indicate that T. maritima endonuclease IV has both phosphodiesterase and phosphomonoesterase activities on 3′-blocking groups.

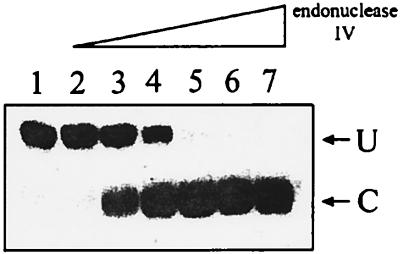

To determine if the enzyme is an AP endonuclease, an AP site-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide was assayed for cleavage. Electrophoretic separation of the products of the reaction on a denaturing acrylamide gel revealed endonucleolytic action at the AP site (Fig. 3). The apparent Km for AP site cleavage was 0.27 μM.

FIG. 3.

AP endonuclease activity of T. maritima endonuclease IV. After treatment of 510 nM double-stranded AP site-containing 19-mer oligonucleotide with increasing concentrations of T. maritima endonuclease IV for 10 min at 65°C, the reaction mixture was electrophoresed on a 20% denaturing acrylamide gel. Only the strand containing the AP site was radioactively labeled on the 5′ end. The radioactively labeled cleaved (C) and uncleaved (U) strands were visualized on a betascope (Biogen). More than 0.5 nM T. maritima endonuclease IV was required to detect the cleaved product. Enzyme concentrations: lane 1, no enzyme; lane 2, 0.5 nM; lane 3, 2.5 nM; lane 4, 5 nM; lane 5, 25 nM; lane 6, 50 nM; lane 7, 500 nM.

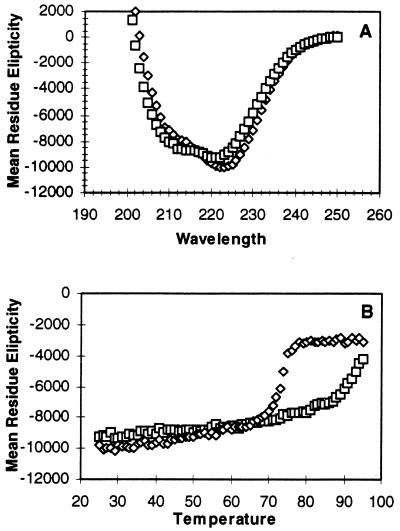

Thermostability analysis.

E. coli endonuclease IV was originally demonstrated to be a heat-stable AP endonuclease, and it retained full activity after an incubation at 65°C (30). In this case, the enzymatic activity was analyzed at 37°C. To determine if E. coli endonuclease IV was active under our assay conditions, we incubated the enzyme at both 37 and 65°C with a substrate containing 3′-incised AP sites and measured the product released. Both E. coli endonuclease IV and T. maritima endonuclease IV are active at both temperatures.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy was used to compare the thermostabilities of the secondary structures of E. coli and T. maritima endonuclease IV. The wavelength scans performed between 200 and 250 nm indicate that both proteins adopt folded structures, with broad minima spanning 208 to 222 nm indicating the presence of secondary structures including alpha helices and beta strands (Fig. 4A). To evaluate the thermostability of the proteins, the absorbance was measured at 222 nm at temperatures ranging from 25 to 95°C. E. coli endonuclease IV is quite heat stable and rapidly begins to denature at 70°C. T. maritima endonuclease IV is more stable than E. coli endonuclease IV; it begins to rapidly denature at 88°C and continues denaturing up to 95°C, the highest temperature evaluated (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy of T. maritima and E. coli endonuclease IV. (A) The circular dichroism spectrum was recorded for both T. maritima (□) and E. coli (◊) endonuclease IV at every nanometer from 200 to 250 nm. The elipticity is measured in degrees square centimeter per decimole. (B) To assess the thermal stability of the proteins, the circular dichroism spectrum was monitored at 222 nm at every degree from 25 to 95°C.

DISCUSSION

We have cloned the gene for endonuclease IV from a hyperthermophilic bacterium, T. maritima. The gene sequence was reconstructed from two partial sequences found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. Sequencing confirms that we have cloned a gene with the sequence deduced from the database. The gene codes for a protein of 32.4 kDa with 32% identity to E. coli endonuclease IV. This is the first endonuclease IV gene to be cloned from a thermophilic organism and only the third endonuclease IV to be purified and characterized for enzymatic activity. The actual protein that we have expressed and purified has a 20-amino-acid extension on the N terminus which includes a six-histidine tag and is truncated by two amino acids on the C terminus.

The purified thermophilic endonuclease IV has the four enzymatic properties associated with the two other functional members of the endonuclease IV family, E. coli endonuclease IV and S. cerevisiae Apn1 (8, 20, 24, 42). We have shown that T. maritima endonuclease IV has AP endonuclease activity, 3′-phosphatase activity, and 3′-repair diesterase activity for phosphoglycolates and trans-4-hydroxy-2-pentenal-5-phosphates. While we have not demonstrated that the T. maritima endonuclease IV gene will give rise to complementation in an nfo mutant E. coli strain, it seems very likely that T. maritima endonuclease IV will have similar activities in vivo and that T. maritima has a base excision repair pathway for various DNA lesions. Sequence gazing allows us to identify a probable endonuclease III homolog in the T. maritima genome. In addition, a uracil DNA glycosylase activity has been identified in crude extracts of T. maritima (22). The full substrate specificity of base excision repair in T. maritima awaits the completion of the genome sequence and further biochemical experiments. Since high temperatures accelerate a number of hydrolytic reactions which degrade DNA (26, 27), it seems likely that base excision repair is important for maintaining the genomic integrity of thermophilic organisms.

Genes coding for potential endonuclease IV homologs have been found in the genomes of approximately 20 species. A number of archaeal genomes contain genes coding for potential endonuclease IV homologs. The cloning of several of these genes is under way, and the expression of active proteins will confirm that the endonuclease IV family of enzymes is also found in the archaea (15b). The distribution of endonuclease IV in phylogeny is limited in the current genomic databases. Further studies are needed to determine if it is a component of most base excision repair pathways or if it has a limited distribution in nature.

Both E. coli and T. maritima enzymes are thermostable. The E. coli enzyme shows activity at 65°C, the highest temperature used with the oligonucleotide substrates that we had prepared. The E. coli enzyme begins to denature at 70°C, as measured by circular dichroism, while the T. maritima enzyme denatures above 88°C. Both enzymes have been crystallized, and their structures have been solved to 1-Å resolution (15a). A comparison of the structures will help us to understand the increased thermostability of the T. maritima enzyme. Structural studies on these enzymes will also reveal details about substrate recognition and catalysis of phosphomonoester and phosphodiester bond cleavage by these metallohydrolases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM46312 to R.P.C. and CA52025 to W.A.F. Sequencing of T. maritima was accomplished with support from the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailly V, Verly W G. AP endonucleases and AP lyases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3617–3618. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barzilay G, Hickson I D. Structure and function of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Bioessays. 1995;17:713–719. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan E, Weiss B. Endonuclease IV of Escherichia coli is induced by paraquat. DNA damage by oxygen-derived species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3189–3193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham R P, Weiss B. Endonuclease III (nth) mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:474–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham R P. DNA glycosylases. Mutat Res. 1997;383:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demple B, Johnson A, Fung D. Exonuclease III and endonuclease IV remove 3′ blocks from DNA synthesis primers in H2O2-damaged Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7731–7735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demple B, Herman T, Chen D S. Cloning and expression of APE, the cDNA encoding the major human apurinic endonuclease: definition of a family of DNA repair enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11450–11454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:915–948. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dianov G, Lindahl T. Reconstitution of the DNA base excision-repair pathway. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doetsch P W, Cunningham R P. The enzymology of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Mutat Res. 1990;236:173–201. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(90)90004-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin W A, Lindahl T. DNA deoxyribophosphodiesterase. EMBO J. 1988;7:3617–3622. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves R J, Felzenszwalb I, Laval J, O’Conner T R. Excision of 5′-terminal deoxyribose phosphate from damaged DNA is catalyzed by the Fpg protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14429–14435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grogan D W. Hyperthermophiles and the problem of DNA instability. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1043–1049. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Guan, Y., D. Hosfield, B. Haas, R. Cunningham, and J. Tainer. Unpublished observations.

- 15b.Haas, B., and R. Cunningham. Unpublished observations.

- 16.Halliwell B, Aruoma O I. Its mechanism and measurement in mammalian systems. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henner W D, Grunberg S M, Haseltine W A. Enzyme action at 3′ termini of ionizing radiation-induced DNA strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:15198–15205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins D G, Thompson J D, Gibson T J. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchinson F. Chemical changes induced in DNA by ionizing radiation. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1985;32:115–154. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson A W, Demple B. Yeast DNA 3′-repair diesterase is the major cellular apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease: substrate specificity and kinetics. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18017–18022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Institute for Genomic Research. Preliminary T. maritma sequence data. [Online.] http://www.tigr.org. [9 September 1997, last date accessed.]

- 21.Kelly S M, Price N C. The application of circular dichroism to studies of protein folding and unfolding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1338:161–185. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koulis A, Cowan D A, Pearl L H, Saava R. Uracil-DNA glycosylase activities in hyperthermophilic micro-organisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krokan H E, Standal R, Slupphaug R. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem J. 1997;325:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3250001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin J D, Johnson A W, Demple B. Homogeneous Escherichia coli endonuclease IV. Characterization of an enzyme that recognizes oxidative damage in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8066–8071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin J D, Demple B. Analysis of class II (hydrolytic) and class I (beta-lyase) apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases with a synthetic DNA substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5069–5075. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Heat-induced deamination of cytosine residues in deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3405–3410. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ljungquist S, Lindahl T, Howard-Flanders P. Methyl methane sulfonate-sensitive mutant of Escherichia coli deficient in an endonuclease specific for apurinic sites in deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:646–653. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.646-653.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ljungquist S. A new endonuclease from Escherichia coli acting at apurinic sites in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:2808–2814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeb L A, Preston B D. Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masson J Y, Tremblay S, Ramotar D. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene CeAPN1 encodes a homolog of Escherichia coli and yeast apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. Gene. 1996;179:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazumder A, Gerlt J A, Absalon M J, Stubbe A, Cunningham R P, Withka J, Bolton P H. Stereochemical studies of the beta-elimination reactions at aldehydic abasic sites in DNA: endonuclease III from Escherichia coli, sodium hydroxide, and Lys-Trp-Lys. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1119–1126. doi: 10.1021/bi00218a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikawa T, Kato R, Sugahara M, Kuramitsu S. Thermostable repair enzyme for oxidative DNA damage from extremely thermophilic bacterium, Thermus thermophilus HB8. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:903–910. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramotar D. The apurinic-apyrimidinic endonuclease IV family of DNA repair enzymes. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramotar D, Vadnais J, Masson J, Tremblay S. Schizosaccharomyces pombe apn1 encodes a homologue of the Escherichia coli endonuclease IV family of DNA repair proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1396:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandigursky M, Franklin W A. DNA deoxyribophosphodiesterase of Escherichia coli is associated with exonuclease I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4699–4703. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.18.4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandigursky M, Lalezari I, Franklin W A. Excision of sugar-phosphate products at apurinic/apyrimidinic sites by DNA deoxyribophosphodiesterase of Escherichia coli. Radiat Res. 1992;131:332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandigursky M, Franklin W A. Exonuclease I of Escherichia coli removes phosphoglycolate 3′-end groups from DNA. Radiat Res. 1993;135:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandigursky M, Mendez F, Bases R E, Matsumato T, Franklin W A. Protein-protein interactions between the Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein and exonuclease I. Radiat Res. 1996;145:619–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siwek B, Bricteux-Gregoire S, Bailly V, Verly W G. The relative importance of Escherichia coli exonuclease III and endonuclease IV for the hydrolysis of 3′-phosphoglycolate ends in polydeoxynucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5031–5038. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.11.5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thayer M, Ahern H, Xing D, Cunningham R P, Tainer J A. Novel DNA binding motifs in the DNA repair enzyme endonuclease III crystal structure. EMBO J. 1995;14:4108–4120. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yajko D M, Weiss B. Mutations simultaneously affecting endonuclease II and exonuclease III in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:688–792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warner H R, Demple B F, Deutsch W A, Kane C M, Linn S. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in repair of pyrimidine dimers and other lesions in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4602–4606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]