Abstract

Our working hypothesis is that a hypoadenosinergic state is a main pathogenetic factor that determines the sensory-motor symptoms and hyperarousal of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS). We have recently demonstrated that brain iron deficiency (BID) in rodents, a well-accepted animal model of RLS, is associated with a generalized downregulation of adenosine A1 receptors (A1R) in the brain and with hypersensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals. Here, we first review the experimental evidence for a pivotal role of adenosine and A1R in the control of striatal glutamatergic transmission and the rationale for targeting putative downregulated striatal A1R in RLS patients, which is supported by recent clinical results obtained with dipyridamole, an inhibitor of the nucleoside transporters ENT1 and ENT2. Second, we perform optogenetic-microdialysis experiments in rats to demonstrate that A1R determine the sensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals and the ability of dipyridamole to counteract optogenetically-induced corticostriatal glutamate release in both animals with BID and controls. Thus, a frequency of optogenetic stimulation that was ineffective at inducing cortico-striatal glutamate release in control rats became effective with the local perfusion of a selective A1R antagonist. Furthermore, in animals with and without BID, the striatal application of dipyridamole blocked the optogenetic-induced glutamate release and decreased basal levels of glutamate, which was counteracted by the A1R antagonist. The results support the clinical application of ENT1 inhibitors in RLS.

Keywords: Adenosine, adenosine A1 receptor, glutamate, striatum, equilibrative nucleoside transporter, dipyridamole, Restless Legs Syndrome

1. INTRODUCTION

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) can be pathophysiologically separated into two clinical phenomena: Deficits of sensorimotor integration that produce akathisia and periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS) and an enhanced arousal state (hyperarousal) (Ferré, García-Borreguero, Allen & Earley, 2018a). Akathisia is described as a feeling of restlessness and an urgent need to move. PLMS have very specific characteristics: they consist on repetitive episodes of leg movement activity (at least 4 in a row) with a duration of up to 10 seconds and an inter-movement interval of 5 to 90 seconds (Ferri, 2012). Hyperarousal manifests, first, as a short sleep time with episodes of arousals during sleep, related but not caused by PLMS; thus, in about half of all cases, the onset of the episodes of arousal precedes the onset of the leg movements (Ferri, Rundo, Zucconi, Manconi, Bruni, Ferini-Strambi et al., 2015). Second, hyperarousal manifests as a lack of profound sleepiness during the day, which would be expected given the significant sleep loss at night (Allen, Stillman & Myers, 2010).

Altered dopaminergic function plays an important role in PLMS and akathisia in RLS, which is supported by the remarkable initial therapeutic response with L-dopa and dopamine D2-like receptor agonists, such as pramipexole and ropinirole (Earley, Connor, Garcia-Borreguero, Jenner, Winkelman, Zee et al., 2014). But there is also evidence for biochemical alterations in the dopaminergic system. The dopaminergic profile in postmortem tissue from RLS patients includes an increased tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity in the substantia nigra and in the striatum and a decreased density of striatal dopamine D2 receptors (D2R), compatible with a presynaptic hyperdopaminergic state, where downregulation of D2R would represent an adaptive postsynaptic effect of an increased dopamine synthesis and release (Earley et al., 2014). In fact, the clinical dopaminergic profile in RLS patients includes abnormally high CSF levels of the dopamine metabolite 3-ortho-methyldopa (3-OMD), interpreted to indicate increased TH activity (Allen, Connor, Hyland, & Earley, 2009).

On the other hand, dopamine receptor agonists are little effective for the hyperarousal component of RLS, where glutamatergic mechanisms seem to be involved. A study by Allen et al. (Allen, Barker, Horská, & Earley, 2013), using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in subjects with RLS compared to controls, showed an increased thalamic concentration of glutamate, which correlated with the time spent awake during the sleep period. These findings therefore suggested a presynaptic hyperglutamatergic state in RLS that could be involved with the hyperarousal state, but also with the sensory-motor symptoms of RLS. In fact, glutamatergic mechanisms play a central role in the therapeutic effects of α2δ-ligands, such as gabapentin, which are effective for both the sensory-motor symptoms and the hyperarousal (Garcia-Borreguero, Patrick, DuBrava, Becker, Lankford, Chen et al., 2014). Thus, α2δ-ligands target the α2δ-subunits of calcium channels localized in glutamatergic terminals, inhibiting glutamate release (Dooley, Taylor, Donevan & Feltner, 2007).

Brain iron deficiency (BID) is now well recognized as a main initial pathophysiological mechanism in the development of RLS, which is supported by results obtained from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and from brain imaging and postmortem studies (Earley et al., 2014). BID in RLS seems to result from alterations of iron acquisition by the brain, a dysregulation of iron transportation by the blood-brain barrier (Earley et al., 2014). The involvement of BID in RLS is promoting the use of iron therapy in refractory RLS, as shown in the Mayo Clinic recommendations (Silber, Becker, Earley, Garcia-Borreguero & Ondo, 2013). BID in rodents during the postweaning period represents a valid pathogenetic model of RLS, since it recapitulates, not only similar behavioral changes of RLS (Dean, Allen, O’Donnell & Earley, 2006; Lai, Cheng, Hsieh, Nguyen, Chew, Ramanathan, et al., 2017), but also the main observed biochemical changes, such as the presynaptic hyperdopaminergic state, with the increase in striatal and nigral TH activity and the reduced striatal density of D2R (Connor, Wang, Allen, Beard, Wiesinger, Felt et al., 2009). It has been suggested that the chain of events that connect BID to an increase in TH expression involves a BID-induced increase in the expression of the hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1 α) (Earley et al., 2014). However, increased striatal TH activity could also be secondary to increased striatal glutamatergic transmission (see below).

We recently obtained the first clear experimental evidence for a BID-dependent increase in presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the BID rat model of RLS, using a new in vivo optogenetic-microdialysis method (Yepes, Guitart, Rea, Newman, Allen, Earley et al., 2017). In this method, a virus expressing the light-sensitive ion channel channelrhodopsin and a green fluorescent protein is injected in the cortex and, after some weeks, channelrhodopsin is selectively expressed by striatal glutamatergic terminals. Then, a microdialysis probe with an embedded optical fiber is implanted in the striatum, which allows the measurement of light-induced stimulation of glutamate release by corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals (Quiroz, Orrú, Rea, Ciudad-Roberts, Yepes, Britt et al., 2016a). The method also allows the analysis of the effect of the local perfusion of different drugs directly within the same area being sampled for glutamate (Quiroz et al., 2016a). The study showed that BID in rats produces hypersensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals, which released glutamate with lower frequency of optogenetic stimulation than controls (60 Hz versus 100 Hz) (Yepes et al., 2017). We hypothesized that BID-induced hypersensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals represents a main pathogenetic mechanism involved in the sensory-motor symptoms of RLS (Yepes et al., 2017). Since we previously demonstrated that optogenetically-induced glutamate release from corticostriatal terminals locally induces striatal dopamine release, we also hypothesized that hypersensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals could also be involved in the BID-induced hyperdopaminergic state of RLS (Ferré et al., 2018a; Ferré, Quiroz, Guitart, Rea, Seyedian, Moreno et al., 2018b). Significantly, local application of either the α2δ ligand gabapentin or the dopamine receptor agonists pramipexole or ropinirole blocked completely glutamate release induced by optogenetic stimulation, both in controls (at 100 Hz) and in animals with BID (at 60 Hz) (Yepes et al., 2017). This implied that dopamine receptors and voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCC) expressing α2δ units localized in striatal glutamatergic terminals might represent key targets for the therapeutic effects of both dopamine receptor agonists and α2δ ligands in RLS. The apparently inexplicable efficacy of dopamine receptor agonists in the frame of a hyperdopaminergic state could then be explained by their action on presynaptic, and not postsynaptic, striatal dopamine receptors. Activation of presynaptic dopamine receptors localized in glutamatergic terminals would locally inhibit glutamate-dependent dopamine release. An additional implication is that the use of the optogenetic-microdialysis method in BID rats provides an animal model to screen new putative therapeutically effective treatments for RLS (Yepes et al., 2017).

Adenosine plays an important modulatory role of the function of corticostriatal terminals. This control is mediated by adenosine A1 and A2A receptors (A1R and A2AR), which establish intermolecular interactions forming A1R-A2AR heteromers (Ciruela, Casadó, Rodrigues, Luján, Burgueño, Canals et al., 2006; Navarro, Cordomí, Brugarolas, Moreno, Aguinaga, Pérez-Benito et al., 2018a). These heteromers work as an adenosine concentration-dependent switch, which determines opposite effects of adenosine on glutamate release depending on a predominant A1R or A2AR activation in the heteromer. Adenosine has more affinity for A1R than for A2AR and, therefore, low concentrations of adenosine activate A1R, which induces an inhibition of glutamate release. On the other hand, with high concentrations of adenosine (obtained upon conditions of strong glutamatergic input, with the consequent neuronal and glial ATP release and conversion of ATP on adenosine), simultaneous activation of the A2AR leads to allosteric interactions that lead to a decrease in the affinity and efficacy of adenosine for the A1R (Ciruela et al., 2006; Navarro et al., 2018a). The molecular mechanisms of these allosteric interactions are beginning to be understood and they are related to the specific tetrameric quaternary structure of the A1R-A2AR heteromer (Navarro et al., 2018a).

We have recently shown that BID in rodents causes a generalized downregulation of A1R in the brain (Quiroz, Gulyani, Ruiqian, Bonaventura, Cutler, Pearson et al., 2016b). Based on these results, we have hypothesized that a hypoadenosinergic state, secondary to A1R downregulation, could be mostly responsible for the hyperglutamatergic and hyperdopaminergic states of RLS that determine the sensory-motor symptoms of RLS as well as the hyperarousal component (Ferré et al., 2018a,b). More specifically, in view of the key inhibitory role of A1R on striatal glutamate release, A1R downregulation should be mostly responsible for the BID-induced hypersensitivity of corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals (Ferré et al., 2018a,b). We therefore predicted that equilibrative nucleoside transporter inhibitors, by increasing the striatal extracellular levels of adenosine (which would facilitate the binding probability of adenosine to the lower expressed A1R; see Discussion), could provide a new therapeutic approach for RLS. In fact, we have recently reported encouraging results with the non-selective ENT1/ENT2 dipyridamole in an open trial with RLS patients (García-Borreguero, Guitart, Garcia Malo, Cano-Pumarega, Granizo & Ferré S, 2018). The goal of the present study was to further support the A1R-dependent hypoadenosinergic-state hypothesis and its involvement in the BID-induced hypersensitivity of corticostriatal terminals, as well as its possible therapeutic implications. Our preclinical and clinical studies would predict that striatal application of an A1R blocker should produce hypersensitivity of corticostriatal terminals. We would then expect that, the same way as in rats with BID, in naïve rats, an A1R antagonist should reduce the frequency of optogenetic stimulation necessary to induce corticostriatal glutamate release. Furthermore, dipyridamole, by increasing the striatal extracellular concentration of adenosine and the activation of presynaptic A1R, should be able to counteract optogenetic-induced glutamate release in both naïve rats and in rats with BID. Finally, we would also expect that this putative effect of dipyridamole should be counteracted by an A1R blocker.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley albino rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), weighing 100–150 grams and 280–360 g at the time of the first and second surgeries, respectively, were used in the experiments. Animals were housed 2 per cage and kept on a 12/12-h dark/light cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All animals used in the study were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Animal Care and the animal research conducted to perform this study was approved by the NIDA IRP Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #: 15-BNRB-73). The rats were divided into two groups: the control group was fed with a diet containing an essential amount of iron (48 ppm iron, Catalog TD.80394, Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI) and the BID group was fed with a diet containing a low iron concentration (4 ppm iron, Catalog TD.80396, Harlan-Teklad). The other contents of the diet were the same. Diets were started immediately after weaning, at 21 days of age, and continued for four weeks, when microdialysis experiments were performed.

Assessment of iron deficiency

Systemic iron deficiency was assessed by measuring the hematocrit content from blood collected before perfusion at the end of the microdialysis experiments to control for the efficiency of the iron-deficient diet. A hematocrit below 20% indicated a successful diet, as we previously showed in our previous studies that it is associated with significant BID (Quiroz, Pearson, Gulyani, Allen, Earley & Ferré 2010; Yepes et al., 2017).

Surgical procedures

Four weeks before the microdialysis experiments, the animals, weighing between 100 to 150 grams, were anesthetized with 3 ml/kg of Equithesin (4.44 g of chloral hydrate, 0.972 g of Na pentobarbital, 2.124 g of MgSO4, 44.4 ml of propylene glycol, 12 ml of ethanol and distilled H2O up to 100 ml of final solution; NIDA Pharmacy, Baltimore, MD). A unilateral injection of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) fused to enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (EYFP) under control of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) neuronal promoter (AAV-CaMKIIa-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP; University of North Carolina core vector facility) was delivered in the agranular motor cortex; coordinates of injection were 2.5 mm anterior, 3 mm lateral and −5 mm ventral with respect to bregma). Virus (0.5 μl of purified and concentrated AAV; 1 × 1012 infectious units/ml) was injected using a 105 μm-thick silica tubing injector coupled directly to a 1 μl-syringe driven by an infusion pump. Virus suspension was injected over a 10-min period at a rate of 50 nl/min and the injector was left in place for an additional ten minutes to allow diffusion of the suspension. Four weeks after virus injection, with the rats weighing 280 to 360 grams, a modified microdialysis probe (optogenetic-microdialysis probe) with an embedded light-guiding optic fiber (see below) was implanted into the lateral striatum under Equithesin anesthesia (3 ml/kg); coordinates were 0 mm anterior, 4.5 lateral and −7 mm ventral with respect to bregma. The probes were fixed to the skull with stainless steel screws and dental glassionomer cement.

Intracranial optogenetic stimulation

An optogenetic-microdialysis probe with a 125 μm-diameter optic fiber (0.22 numerical aperture) embedded in a microdialysis probe was used for optogenetic stimulation of glutamate release by cortico-striatal terminals (Quiroz et al., 2016a; Yepes et al., 2017). The tip of the optic fiber was given a conical shape to allow a local light dispersion through and around the working portion of the dialyzable membrane. The conical sculpted tip with the cladding fused to the core was obtained by pulling the fiber with a Flamming-Brown pipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), fitted with a custom platinum heating filament of circular cross-section (1 mm in diameter) and a holder specifically designed for the diameter of the optic fiber. Optical stimulation was delivered coupling the light guiding port of the implanted optogenetic-microdialysis probe to a 473-nm solid-state laser module driven by an electrical stimulator (Grass S88 stimulator). Light pulses were applied over a 20-min period in 160-ms trains of 1-ms pulses at a frequency of 60 or 100 Hz and intensity of 5–8 mW at the probe tip (one train/s). Light intensity at the probe tip was measured before implantation using an integrating sphere silicon photodiode power sensor designed for optical power measurements independent of beam shape and divergence (model S144C, Thor Labs, Newton, NJ).

In vivo microdialysis

Microdialysis sampling was performed to analyze the extracellular concentrations of striatal glutamate of freely moving rats 24 h after probe implantation. An artificial cerebrospinal solution (aCSF; 144 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.7 CaCl2, and 1.2 MgCl2, in mM) with or without the A1R antagonist cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT; 300 μM, Millipore-Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) or the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole (1 μM; Tocris-Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN), was pumped through the optogenetic-microdialysis probe at a constant rate of 1 μl/min. After a washout period of 90 min, dialysate samples were collected for 60 min of baseline sampling at 20-min intervals. After baseline sampling, optogenetic stimulation was applied for 20 min and 20-min samples were taken for 80 additional min after the beginning of the stimulation. Glutamate content was measured by HPLC coupled to a glutamate oxidase enzyme reactor and electrochemical detector (Eicom, San Diego, CA). At the end of the microdialysis experiment, animals were deeply anesthetized with Equithesin and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), followed by 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4. Brains were stored in the same fixative and then transferred into a solution of 20% sucrose/0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, solution for 48 h at 4°C. Forty-μm coronal sections were cut in a Leica (Nussloch, Germany) CM3050S cryostat at −20°C, collected in PBS, and stored in antifreeze-buffered solution (20% ethylene glycol, 10% glycerol, and 10% sucrose in PBS) at −80°C until processing. Sections were then evaluated for probe localization and ChR2-EYFP expression using a Typhoon multimode laser scanner (GE life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Confocal fluorescence microscopy images were acquired with a Zeiss microscope (Examiner Z1, Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) fitted with a confocal laser module (LSM-710, Zeiss).

3. RESULTS

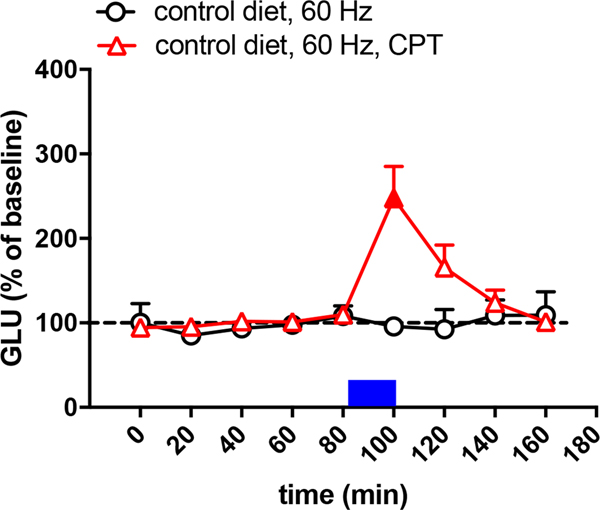

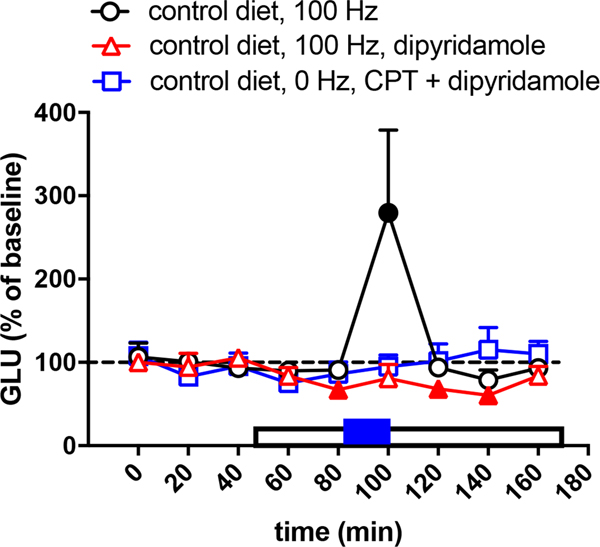

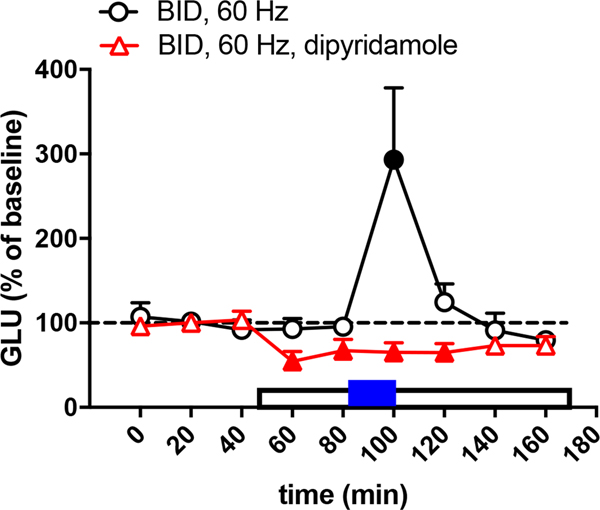

As shown in a previous study (Yepes et al., 2017), in animals with a control diet, a frequency of optogenetic stimulation of 60 Hz did not produce striatal glutamate release (circles in Fig. 1), while 100 Hz produced a significant effect (circles in Fig. 2). Also, as previously shown (Yepes et al., 2017), the corticostriatal terminals of animals with BID were more sensitive to the optogenetic stimulation and glutamate release was obtained with the lower frequency, at 60 Hz (circles in Fig. 3). Nevertheless, 60 Hz also produced glutamate release in animals with control diet with perfusion of the A1R antagonist CPT (triangles in Fig. 1), indicating that A1R blockade increases the sensitivity of the corticostriatal terminals to release glutamate. The concentration of CPT perfused through the microdialysis probe (300 μM) was previously shown to be effective at modulating striatal glutamate release by selectively acting on presynaptic A1R (Quarta, Borycz, Solinas, Patkar, Hockemeyer, Ciruela et al., 2004; Borycz, Pereira, Melani, Rodrigues, Köfalvi, Panlilio et al., 2007). In rats with a control diet, perfusion of the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole (1 μM) produced a small but significant decrease in the basal striatal extracellular concentration of glutamate before and after the optogenetic stimulation (80-min, 120-min and 140-min samples in Fig. 2; triangles). In addition, dipyridamole completely blocked glutamate release induced by optogenetic stimulation (100-min sample in Fig. 2; tiangles). The specific involvement of A1R on the effects of dipyridamole could be confirmed by the ability of CPT (300 μM) to counteract the dipyridamole-induced decrease in the basal extracellular levels of glutamate (80-min, 120-min and 140-min samples in Fig. 2; squares). These results, therefore confirm the A1R-mediated effects of dipyridamole. Importantly, in rats with BID, dipyridamole also decreased basal levels of glutamate (60-min, 80-min and 120-min samples in Fig. 3; triangles) and optogenetic-induced increase in extracellular concentration of glutamate (100-min sample in Fig. 3; triangles). These results validate once more the use of the optogenetic-microdialysis method in BID rats as a model to identify new pharmacological treatments for RLS (see Discussion).

Figure 1.

Glutamate release induced by low-frequency (60 Hz) of optogenetic stimulation of the corticostriatal terminals in the lateral striatum of rats with control diet with (triangles) and without (circles) perfusion of the A1R antagonist CPT (300 μM). CPT is constantly perfused since the beginning of glutamate sampling and the period of optogenetic stimulation (20 min) is represented by a blue rectangle. Results are expressed as means + S.E.M. of percentage of the average of the first three basal values (n = 9 and 7 per group). Filled symbols represent significantly different means as compared to the mean of the first three basal values (p<0.05; repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test).

Figure 2.

Glutamate release induced by high-frequency (100 Hz) of optogenetic stimulation of the corticostriatal terminals in the lateral striatum of rats with control diet with (triangles) and without (circles) perfusion of the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole (1 μM). The plot with squares represents the effect of co-perfusion of the A1R antagonist CPT (300 μM) and dypyridamole (1 μM), without optogenetic stimulation. CPT is constantly perfused since the beginning of glutamate sampling. The period of dipyridamole perfusion is represented by an empty rectangle and the period of optogenetic stimulation (20 min) is represented by a blue rectangle. Results are expressed as means + S.E.M. of percentage of the average of the first three basal values (n = 7–8 per group). Filled symbols represent significantly different means as compared to the mean of the first three basal values (p<0.05; repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test).

Figure 3.

Glutamate release induced by low-frequency (60 Hz) of optogenetic stimulation of the corticostriatal terminals in the lateral striatum of rats with BID with (triangles) and without (circles) perfusion of the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole (1 μM). The period of dipyridamole perfusion is represented by an empty rectangle and the period of optogenetic stimulation (20 min) is represented by a blue rectangle. Results are expressed as means + S.E.M. of percentage of the average of the first three basal values (n = 7–8 per group). Filled symbols represent significantly different means as compared to the mean of the first three basal values (p<0.05; repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test).

4. DISCUSSION

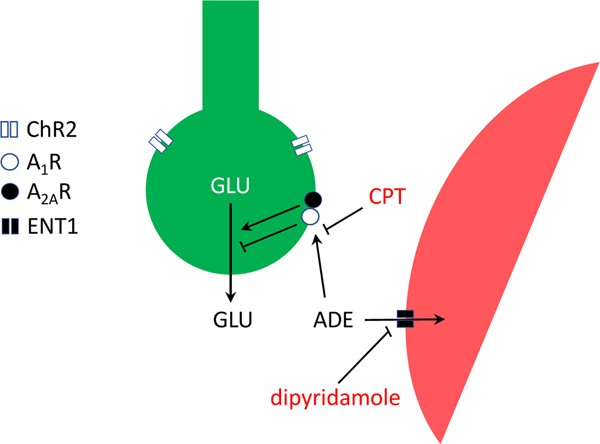

The results of the present experiments support our hypothesis of a key role of adenosine and A1R in the modulation of corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission and their possible use as targets for drug development in RLS. In addition, they confirm the preclinical efficacy of the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole in the BID rodent. As previously predicted (Ferré et al., 2018b), dipyridamole counteracted optogenetically-induced glutamate release by corticostriatal terminals in naïve and BID rats. The results of the present experiments are schematically summarized in Fig. 4, which implies that manipulations of the endogenous levels of adenosine or its binding potential (BP) to the A1R significantly determine the sensitivity of corticostriatal nerve terminals to release glutamate.

Figure 4.

Scheme representing the A1R-mediated modulation glutamate release by corticostriatal terminals (in green). The ability of endogenous adenosine (ADE) to inhibit glutamate release under basal conditions or upon optogenetic stimulation of channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2)-expressing terminals is increased by blocking its transport to astrocytes (in red) with the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole or by blocking its binding to A1R with the A1R antagonist CPT.

BP is an operational measure of receptor occupancy by an endogenous or exogenous ligand, which determines the instantaneous functional receptor response, and is denoted as the product of maximum density of the receptor (Bmax) and the affinity of the specific ligand to its receptor (i.e. BP = Bmax x 1/KD) (Mintun, Raichle, Kilbourn, Wooten & Welch,1984). According to the Law of Mass Action, the rate of any reaction is proportional to the concentrations of the reactants. Applied to ligand-receptor interactions, the concentration of ligand-receptor complex (receptor occupancy and, therefore, receptor activation when the ligand is an agonist) depends on the concentration of ligand and receptor (receptor density) and to the affinity of the ligand for the receptor. This is, nevertheless, an oversimplification and there are additional factors that determine the ligand-receptor encounter probability, such as receptor clustering, which increases rebinding probability. Recent studies are providing strong evidence for pre-coupling of specific receptors and their specific associated signaling proteins and effectors (Navarro, Cordomí, Casadó-Anguera, Moreno, Cai, Cortés et al., 2018b). These macromolecular complexes can form high-order oligomers that include the same and different receptors (receptor heteromers), allowing, not only the very efficient receptor response upon very low concentrations of the ligands (Civciristov, Ellisdon, Suderman, Pon, Evans, Kleifeld et al., 2018), but also very specific interactions between different ligands at specific effectors (Navarro et al., 2018b). In any case, here we use the concepts of binding and ligand-receptor encounter probability to provide the rationale for increasing the concentration of the endogenous ligand (adenosine) to compensate the decrease in the density of its receptor (A1R).

Our pathogenetic working hypothesis in RLS, a BID-induced A1R downregulation that leads to hypersensitive corticostriatal glutamatergic terminals (Ferré et al., 2018a,b), would imply a decrease in the BP of endogenous adenosine and would predict that dipyridamole should lead to an increase in the occupancy of A1R by increasing the concentration of endogenous adenosine. The BID-induced decrease in adenosine BP to A1R was mimicked by the A1R antagonist CPT, which expectedly produced hypersensitivity of corticostriatal terminals. In addition, dipyridamole significantly reduced, through an A1R-dependent mechanism (blocked by CPT), optogenetically-induced cortico-striatal glutamate release in naïve and BID rats.

An interesting result of the present study is the complete blockade of optogenetically-induced glutamate release produced by the A1R-mediated effect of dipyridamole, which is in contrast with the previously reported partial inhibitory effect of A1R agonists (at most, 50%) observed in synaptosomal preparations of not only striatal, but also hippocampal, cortical and spinal tissue (Ambrósio, Malva, Carvalho & Carvalho, 1997; Marchi, Raiteri, Risso, Vallarino, Bonfanti, Monopoli et al., 2002; Li & Eisenach, 2005; Ciruela et al., 2006). One plausible explanation is the presence of additional A1R-modulated cellular components in the in vivo microdialysis preparation, such as the cholinergic interneurons. Thus, corticostriatal inputs directly activate cholinergic interneurons (Kosillo, Zhang, Threlfell & Cragg, 2016) and striatal acetylcholine release promotes glutamate release by activation of α7-nicotinic receptors localized in the corticostriatal terminals (Kaiser & Wonnacott, 2000; Quarta et al., 2004). The cholinergic component of glutamate release can then be modulated by adenosine, which exerts a significant inhibitory control of the excitability of the striatal cholinergic interneurons by acting on A1R, their predominantly expressed adenosine receptor subtype (Song, Tkatch & Surmeier, 2000). Astrocytes could also constitute an additional significant player, since they are believed to amplify neuronal glutamate release and they also express A1R (Daré, Schulte, Karovic, Hammarberg & Fredholm, 2007; Ferré, Agnati, Ciruela, Lluis, Woods, Fuxe et al., 2007).

In the brain, adenosine uptake occurs primarily by facilitated diffusion via equilibrative transporters, which inhibition leads to an increase in the extracellular concentration of adenosine (Parkinson, Damaraju, Graham, Yao, Baldwin, Cass et al., 2011; Dulla & Masino, 2013; Cunha, 2016). There are four different subtypes of equilibrative transporters, ENT1-ENT4, from which ENT1 and ENT2 are the most expressed in the brain, predominantly in astrocytes, but also in neurons (Parkinson et al., 2011). In fact, astrocytes are also the main source of extracellular adenosine, released as ATP and rapidly converted in adenosine by means of ecto-nucleotidases (Dulla & Masino, 2013; Cunha, 2016), and it has been demonstrated that astrocytic ATP release plays a major in the A1R-mediated regulation of adenosine on presynaptic glutamate transmission (Hines & Haydon, 2013). Some studies indicate that ENT1 plays a more salient role than ENT2 in determining the extracellular concentration of adenosine in the brain (Alanko, Porkka-Heiskanen & Soinila, 2006), and ENT1 (but not ENT2) is often regionally co-localized with A1R, supporting a more significant role of ENT1 in the transport of adenosine that controls A1R function (Jennings, Hao, Cabrita, Vickers, Baldwin, Young et al., 2001). Therefore, it would be desirable to develop still non-available selective ENT1 inhibitors.

Meanwhile, apart from the present preclinical results, there are two additional reasons that support the clinical use of the ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole in RLS patients, instead of selective A1R agonists. First, selective A1R agonists cannot be used clinically because of their strong cardiovascular side effects, bradycardia and hypotension (Schindler, Karcz-Kubicha, Thorndike, Müller, Tella, Ferré et al., 2005). Second, dipyridamole is already extensively used clinically as antiplatelet, to prevent stroke and heart attack, with relatively infrequent side effects (Kim & Liao, 2008). However, the possible use of dipyridamole (and other ENT1/ENT2 inhibitors) for RLS could be questioned in view of its previously reported low brain penetrability (Sollevi, 1986; Parkinson et al., 2011). Nevertheless, we recently demonstrated its ability to modulate postsynaptic striatal A1R and A2AR with systemic administration of dipyridamole in reserpinized mice (Ferré et al., 2018b). Furthermore, as predicted from the “hypoadenosinergic state” hypothesis of RLS pathophysiology, an open trial of dipyridamole with 15 untreated idiopathic RLS patients provided very encouraging results (García-Borreguero et al., 2018). These preliminary results suggest that dipyridamole has significant therapeutic effects, not only on the sensory-motor symptoms, but also for the hyperarousal. Thus, as recently reviewed (Ferré et al., 2018a), A1R downregulation in areas that control the ascending arousal systems might be also a main pathogenetic mechanism involved in the hyperarousal and sleep disruption in RLS. These clinical results, nevertheless, need now to be consolidated with a placebo-controlled study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Work supported by the intramural funds of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

ABBREVIATIONS

- A1R

adenosine A1 receptor

- A2AR

adenosine A2A receptor

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- BID

brain iron deficiency

- BP

binding potential

- CAMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- ChR2

channelrhodopsin 2

- CPT

cyclopentyltheophylline

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- D2R

dopamine D2 receptor

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescence protein

- ENT

equilibrative nucleoside transported

- PLMS

periodic limb movements during sleep

- RLS

Restless Legs Syndrome

- TfR

transferrin receptor

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VDCC

voltage-dependent calcium channels

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Alanko L, Porkka-Heiskanen T, & Soinila S.(2006). Localization of equilibrative nucleoside transporters in the rat brain. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, 31, 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Connor JR, Hyland K, & Earley CJ (2009). Abnormally increased CSF 3-Ortho-methyldopa (3-OMD) in untreated restless legs syndrome (RLS) patients indicates more severe disease and possibly abnormally increased dopamine synthesis. Sleep Medicine, 10, 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Stillman P, & Myers AJ (2010). Physician-diagnosed restless legs syndrome in a large sample of primary medical care patients in western Europe: Prevalence and characteristics. Sleep Medecine, 11, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Barker PB, Horská A, & Earley CJ (2013). Thalamic glutamate/glutamine in restless legs syndrome: increased and related to disturbed sleep. Neurology, 80, 2028–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrósio AF, Malva JO, Carvalho AP, & Carvalho CM (1997). Inhibition of N-,P/Q- and other types of Ca2+ channels in rat hippocampal nerve terminals by the adenosine A1 receptor. European Journal of Pharmacology, 340, 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz J, Pereira MF, Melani A, Rodrigues RJ, Köfalvi A, Panlilio L, et al. (2007). Differential glutamate-dependent and glutamate-independent adenosine A1 receptor-mediated modulation of dopamine release in different striatal compartments. Journal of Neurochemistry, 101, 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F, Casadó V, Rodrigues RJ, Luján R, Burgueño J, Canals M, et al. (2006). Presynaptic control of striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission by adenosine A1-A2A receptor heteromers. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2080–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civciristov S, Ellisdon AM, Suderman R, Pon CK, Evans BA, Kleifeld O, et al. (2018). Preassembled GPCR signaling complexes mediate distinct cellular responses to ultralow ligand concentrations. Science Signaling, 11, 551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JR, Wang XS, Allen RP, Beard JL, Wiesinger JA, Felt, B. T., et al. (2009). Altered dopaminergic profile in the putamen and substantia nigra in restless leg syndrome. Brain, 132, 2403–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA (2016). How does adenosine control neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration? Journal of Neurochemistry, 139, 1019–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daré E, Schulte G, Karovic O, Hammarberg C, & Fredholm BB (2007). Modulation of glial cell functions by adenosine receptors. Physiology and Behavior, 92, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean T Jr., Allen RP, O’Donnell CP, & Earley CJ (2006). The effects of dietary iron deprivation on murine circadian sleep architecture. Sleep Medicine, 7, 634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, & Feltner D.(2007). Ca2+ channel α2δ ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 28, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulla CG, & Masino SA (2013). Physiology and metabolic regulation of adenosine: mechanisms. In Masino S.& Boison D.(Eds.), Adenosine. A Key Link Between Metabolism and Brain Activity (pp. 87–107). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Earley CJ, Connor J, Garcia-Borreguero D, Jenner P, Winkelman J, Zee PC, et al. (2014). Altered brain iron homeostasis and dopaminergic function in Restless Legs Syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease). Sleep Medecine, 15, 1288–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré S, Agnati LF, Ciruela F, Lluis C, Woods AS, Fuxe K, et al. (2007). Neurotransmitter receptor heteromers and their integrative role in ‘local modules’: the striatal spine module. Brain Research Reviews, 55, 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré S, García-Borreguero D, Allen RP, & Earley CJ (2018a). New Insights into the Neurobiology of Restless Legs Syndrome. The Neuroscientist, doi: 10.1177/1073858418791763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré S, Quiroz C, Guitart X, Rea W, Seyedian A, Moreno E, et al. (2018b). Pivotal role of adenosine neurotransmission in restless legs syndrome. Frontiers in Neuroscience 11, 722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri R.(2012). The time structure of leg movement activity during sleep: the theory behind the practice. Sleep Medecine, 13, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri R, Rundo F, Zucconi M, Manconi M, Bruni O, Ferini-Strambi L, et al. (2015). An evidence-based analysis of the association between periodic leg movements during sleep and arousals in Restless Legs Syndrome. Sleep, 38, 919–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Borreguero D, Patrick J, DuBrava S, Becker PM, Lankford A, Chen C, et al. (2014). Pregabalin versus pramipexole: effects on sleep disturbance in restless legs syndrome. Sleep, 37, 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Borreguero D, Guitart X, GarciaMalo C, Cano-Pumarega I, Granizo JJ, & Ferré S.(2018). Treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease with the nonselective ENT1/ENT2 inhibitor dipyridamole: testing the adenosine hypothesis. Sleep Medecine 45, 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DJ, & Haydon PJ (2013). Physiology and metabolic regulation of adenosine: mechanisms. In Masino S.& Boison D.(Eds.), Adenosine. A Key Link Between Metabolism and Brain Activity (pp. 157–177). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings LL, Hao C, Cabrita MA, Vickers MF, Baldwin SA, Young JD, et al. (2001). Distinct regional distribution of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter proteins 1 and 2 (hENT1 and hENT2) in the central nervous system. Neuropharmacology, 40, 722–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, & Wonnacott S.(2000). Alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors indirectly modulate [(3)H]dopamine release in rat striatal slices via glutamate release. Molecular Pharmacology, 58, 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, & Liao JK (2008). Translational therapeutics of dipyridamole. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 28, s39–s42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosillo P, Zhang YF, Threlfell S, & Cragg SJ (2016). Cortical control of striatal dopamine transmission via striatal cholinergic interneurons. Cerebral Cortex, 26, 4160–4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai YY, Cheng YH, Hsieh KC, Nguyen D, Chew KT, Ramanathan L, et al. (2017). Motor hyperactivity of the iron-deficient rat - an animal model of restless legs syndrome. Movement Disorders, 32, 1687–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, & Eisenach JC (2005). Adenosine reduces glutamate release in rat spinal synaptosomes. Anesthesiology, 103, 1060–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi M, Raiteri L, Risso F, Vallarino A, Bonfanti A, Monopoli A, et al. (2002). Effects of adenosine A1 and A2A receptor activation on the evoked release of glutamate from rat cerebrocortical synaptosomes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 136, 434–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Kilbourn MR, Wooten GF, & Welch MJ (1984). A quantitative model for the in vivo assessment of drug binding sites with positron emission tomography. Annals of Neurology, 15, 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Cordomí A, Brugarolas M, Moreno E, Aguinaga D, Pérez-Benito L, et al. (2018a). Cross-communication between G(i) and G(s) in a G-protein-coupled receptor heterotetramer guided by a receptor C-terminal domain. BMC Biology, 16, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Cordomí A, Casadó-Anguera V, Moreno E, Cai N-S, Cortés A, et al. (2018b). Evidence for functional pre-coupled complexes of receptor heteromers and adenylyl cyclase. Nature Communications, 9:1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson FE, Damaraju VL, Graham K, Yao SY, Baldwin SA, Cass CE, et al. (2011). Molecular biology of nucleoside transporters and their distributions and functions in the brain. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 11, 948–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta D, Borycz J, Solinas M, Patkar K, Hockemeyer J, Ciruela F, et al. (2004). Adenosine receptor-mediated modulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens depends on glutamate neurotransmission and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor stimulation. Journal of Neurochemistry, 91, 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz C, Pearson V, Gulyani S, Allen R, Earley C, & Ferré S.(2010). Up-regulation of striatal adenosine A(2A) receptors with iron deficiency in rats: effects on locomotion and cortico-striatal neurotransmission. Experimental Neurology, 224, 292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz C, Orrú M, Rea W, Ciudad-Roberts A, Yepes G, Britt JP, et al. (2016a). Local control of extracellular dopamine levels in the medial nucleus accumbens by a glutamatergic projection from the infralimbic cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 36, 851–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz C, Gulyani S, Ruiqian W, Bonaventura J, Cutler R, Pearson V, et al. (2016b). Adenosine receptors as markers of brain iron deficiency: implications for Restless Legs Syndrome. Neuropharmacology 111, 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Karcz-Kubicha M, Thorndike EB, Müller CE, Tella SR, Ferré S, et al. (2005). Role of central and peripheral adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular responses to intraperitoneal injections of adenosine A1 and A2A subtype receptor agonists. British Journal of Pharmacology, 144, 642–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollevi A.(1986). Cardiovascular effects of adenosine in man; possible clinical implications. Progress in Neurobiology, 27, 319–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WJ, Tkatch T, & Surmeier DJ (2000). Adenosine receptor expression and modulation of Ca(2+) channels in rat striatal cholinergic interneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 83, 322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber MH, Becker PM, Earley C, Garcia-Borreguero D, & Ondo WG; Medical Advisory Board of the Willis-Ekbom Disease Foundation. (2013). Willis-Ekbom Disease Foundation revised consensus statement on the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 88, 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepes G, Guitart X, Rea W, Newman AH, Allen RP, Earley CJ, et al. (2017). Targeting hypersensitive corticostriatal terminals in restless legs syndrome. Annals of Neurology, 82, 951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]