Commissioned and introduced by Associate Editors Irene Roberts and Thomas Ortel, this Review Series focuses on common areas in pediatric hematology practice, emphasizing new therapeutic and diagnostic developments. The specific challenges of managing hemostatic and thrombotic disorders in children are described by O’Brien and Zia. Distinguishing acquired immune diseases from inherited disorders of blood counts is a common problem for pediatric hematologists, and this is tackled in reviews by Grace and Lambert for thrombocytopenias and by Dokal et al for bone marrow failure. Finally, Gallagher provides a stepwise approach to the diagnosis and treatment of anemia in infancy and childhood, at both the individual patient level and the population level.

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Inherited bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes are a diverse group of disorders characterized by BM failure, usually in association with ≥1 extrahematopoietic abnormalities. BM failure, which can involve ≥1 cell lineages, often presents in the pediatric age group. Furthermore, some children initially labeled as having idiopathic aplastic anemia or myelodysplasia represent cryptic cases of inherited BM failure. Significant advances in the genetics of these syndromes have been made, identifying more than 100 disease genes, giving insights into normal hematopoiesis and how it is disrupted in patients with BM failure. They have also provided important information on fundamental biological pathways, including DNA repair: Fanconi anemia (FA) genes; telomere maintenance: dyskeratosis congenita (DC) genes; and ribosome biogenesis: Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and Diamond-Blackfan anemia genes. In addition, because these disorders are usually associated with extrahematopoietic abnormalities and increased risk of cancer, they have provided insights into human development and cancer. In the clinic, genetic tests stemming from the recent advances facilitate diagnosis, especially when clinical features are insufficient to accurately classify a disorder. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using fludarabine-based protocols has significantly improved outcomes, particularly in patients with FA or DC. Management of some other complications, such as cancer, remains a challenge. Recent studies have suggested the possibility of new and potentially more efficacious therapies, including a renewed focus on hematopoietic gene therapy and drugs [transforming growth factor-β inhibitors for FA and PAPD5, a human poly(A) polymerase, inhibitors for DC] that target disease-specific defects.

Introduction

Inherited bone marrow failure (BMF) syndromes are a diverse group of life-threatening disorders, usually presenting in the pediatric age group.1 Although historically these disorders largely included syndromic categories, such as Fanconi anemia (FA), next-generation sequencing has added to the list an increasing number of new genetically defined entities, such as ERCC6L2-associated BMF. The genetic advances have also led to the recognition that some idiopathic cases of BMF/myelodysplasia (MDS) are cryptic forms of recognized syndromes, such as dyskeratosis congenita and FA. The genetic developments also raise an important question as to what should be considered an inherited BMF syndrome. This issue is complicated, because some germline genetic variants can produce very pleiotropic hematological and nonhematological phenotypes, and the associated phenotypes could be easily classified into more than 1 category. In this review, we included entities that are frequently associated with global BMF and/or constitutional cytopenia(s). A discussion of these entities, highlighting the genetic advances and management principles, is given herein. Tables 1-10 provide details on the marked heterogeneity with >100 currently identified disease genes. We also highlighted some newer entities associated with phenotypes varying from BMF to MDS and leukemia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the inherited bone marrow failure syndromes

| FA | DC | SDS | DBA | CDA | CAMT | SCN | New* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inheritance pattern | AR, XLR | XLR, AR | AR | AD | AR | AR | AD | AR |

| AD | AD | XLR | AD | AD | AR | AD | ||

| Somatic abnormalities | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rare | Yes | Rare | Yes |

| Bone marrow failure | AA (90%) | AA (80%) | AA (20%) | RCA | Dysery | Meg | Neut | Yes |

| Short telomeres | Yes | Yes† | Yes | No | No | No | ? | |

| Cancer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chromosome instability | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | ? | No | ? | Yes‡ |

| Genes identified | 22 | 16 | 4 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 25+ |

CAMT, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and syndromic thrombocytopenia; Dysery, usually dyserythropoiesis; Meg, typically low megakaryocytes, but can progress to global bone marrow failure; Neut, usually low neutrophils; RCA, red cell aplasia, although some patients can develop global bone marrow failure; XLR, X-linked recessive.

Includes new and overlapping syndromes.

Yes, usually very short in DC and short in FA and SDS.

Yes, only some new subtypes are currently known to show chromosome instability.

Table 10.

New BMF and overlapping syndromes

| Subtype | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recently recognized BMF subtypes | |||

| Autosomal recessive | 9q22.32 | ERCC6L2 | 27 |

| 3q27.1 | TPO/THPO | 7 | |

| 1p32.1 | MYSM1 | 23 | |

| 15q21.1 | DUT | 9 | |

| 19q13.32 | EXOC3L2 | 10 | |

| 17p13.1 | TP53 | 12 | |

| Autosomal dominant | 7q21.3 | SAMD9* | 3 |

| 7q21.2 | SAMD9L* | 6 | |

| 12q13.13 | SP1 | 7 | |

| Familial MDS and leukemia | |||

| Autosomal dominant | 21q22.12 | RUNX1 | 13 |

| 19q13.11 | CEBPA | 1 | |

| 3q26.2 | TERC* | 1 | |

| 5p15.33 | TERT* | 16 | |

| 3q21.3 | GATA2* | 8 | |

| 4q12 | SRP72 | 20 | |

| 10p12.1 | ANKRD26 | 46 | |

| 16q22.1 | ACD/TPP1 | 12 | |

| 12p13.2 | ETV6 | 14 | |

| 5q35.3 | DDX41 | 17 | |

| 20q13.33 | RTEL1 | 35 | |

| 9p13.2 | PAX5 | 11 | |

| 7q21.3 | SAMD9* | 3 | |

| 7q21.2 | SAMD9L* | 6 | |

| 3q26.2 | MECOM* | 23 | |

| 17p13.1 | TP53 | 12 | |

| 12q13.2 | ERBB3 | 28 | |

| 19q13.32 | DHX34 | 21 | |

| Autosomal recessive | 3q21.3 | MBD4 | 8 |

| 3q24 | HLTF | 25 | |

| 3p25.1 | XPC/XPCC | 18 |

Variants in these genes can produce very diverse hematological features, including AA, MDS, and leukemia. They can also produce various extrahematopoietic abnormalities. For example, GATA2 deficiency can be associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and primary lymphedema; SAMD9 disease can be associated with adrenal insufficiency, intrauterine growth restriction, and genital abnormalities; and SAMD9L disease can be associated with neurologic/cerebellar, ophthalmic, and pulmonary complications.

FA

FA was first described by Fanconi in 1927.2 It is usually inherited as an autosomal recessive (AR) trait, but in a small subset of patients, it can be an X-linked recessive disorder. Patients with FA are clinically heterogeneous.3 Typical features include BMF development and an increased predisposition to cancer. Affected individuals may also have ≥1 extrahematopoietic abnormalities, including dermatological (eg, cafe au lait spots), skeletal (eg, radial hypoplasia), genitourinary (eg, single kidney), gastrointestinal (eg, duodenal atresia), and neurological abnormalities (Table 2). Approximately one-third of patients have no overt extrahematopoietic abnormalities. Most patients are diagnosed at the end of the first decade of life; however, some patients are diagnosed in adulthood.

Table 2.

Features of syndromic inherited BMF syndromes

| IBMF Subtype | Hematological | Extrahematological | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA | Single cytopenia, global BMF, MDS, and AML. | Skin (eg, cafe au lait spots), skeletal (eg, radial hypoplasia, short stature, “Fanconi facies”), endocrine, genitourinary (eg, single kidney), gastrointestinal (eg, duodenal atresia), and neurological abnormalities. | Hematological (MDS, AML). Squamous cell carcinoma, especially of the head and neck and vulva. Other tumors (eg, liver) are also observed. |

| DC | Single cytopenia, global BMF, MDS, and AML. | The mucocutaneous triad of abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and mucosal leucoplakia. A variety of other abnormalities, including dental (eg, severe caries), gastrointestinal (eg, esophageal stenosis, cirrhosis), genitourinary (eg, phimosis), neurological (eg, cerebellar hypoplasia), ophthalmic (eg, nasolacrimal duct narrowing, retinopathy), pulmonary (eg, pulmonary fibrosis), skeletal (eg, osteoporosis), and vascular abnormalities. | Hematological (MDS, AML). Squamous cell carcinoma, especially of the head and neck and vulva. Other tumors (eg, liver) are also observed. |

| SDS | Single cytopenia (eg, neutropenia), global BMF, MDS, and AML. | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, skeletal (metaphyseal dysostosis, rib cage defects), failure to thrive, developmental delay, dental, and variable other abnormalities. | Hematological (MDS and AML). |

| DBA | Typically anemia, but can progress to global BMF, MDS, and AML. | Skeletal (triphalangeal thumb), short stature, craniofacial (eg, high arched palate),cardiac, and urogenital malformations. | Hematological (MDS, AML), rarely osteosarcoma and colon cancer. |

| CDA | Anemia with dyserythropoiesis. | Skeletal abnormalities and splenomegaly. | No |

| SCN | Neutropenia, frequently there are myeloid maturation arrest, MDS, and AML. | Usually, none in patients with ELANE variants. There may be extrahematopoietic abnormalities in non-ELANE–bearing patients. | Hematological (MDS and AML). |

| CAMT and other syndromic thrombocytopenias | Thrombocytopenia, BMF, MDS, and AML. | In typical CAMT, there are usually no other physical abnormalities. Patients with TAR have an absence of radius and sometimes other abnormalities. Those with a fusion of radius and ulna can also have skin, skeletal, and other extrahematopoietic defects. | Patients with classic CAMT can develop leukemia. Those with TAR usually have no cancer risk. Patients with radioulnar fusion due to MECOM variants can develop MDS and AML. |

FA cells display hypersensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents, such as diepoxybutane (DEB) and mitomycin C (MMC). This FA cell hallmark led to the development of a diagnostic test several decades ago and has facilitated many advances, including elucidating the genetics with currently characterized 22 FA and FA-like disease subtypes/complementation groups.3-20 The proteins encoded by the FA and FA-like genes (Table 3) participate in DNA repair.21 Specifically, 8 of the FA proteins (FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCL, and FANCM) interact with one another to form a nuclear complex, the FA core complex. The FA core complex is necessary for activation of the FANCI-FANCD2 complex to a monoubiquitinated form (FANCI-FANCD2-Ub). FANCI-FANCD2-Ub then interacts with DNA repair proteins, such as BRCA2, BRCA1, and RAD51, leading to DNA damage repair. Patients with FA type D1 (FA-D1) and those with FA-S have biallelic variants in BRCA2 and BRCA1, respectively. These observations linked FA to the DNA damage-response pathway (Figure 1). BRCA2 is important for DNA damage repair by homologous recombination. Cells lacking BRCA2 inaccurately repair damaged DNA and are hypersensitive to DNA cross-linking agents. It has been established that FANCJ represents BRIP1 (partner of BRCA1) and FANCN represents PALB2 (partner of BRCA2) and that SLX4 is also an FA protein. These findings have strengthened the connection between FA and DNA repair; specifically, the FA network orchestrates incisions at cross-linked DNA sites.22 Recent studies have suggested that the FA proteins are important in counteracting aldehyde-induced genotoxicity in hematopoietic stem cells.23 FA proteins also have other functional roles, including cytokine regulation,24 mitophagy, and ribosome biogenesis.25 The multifunctional biological roles of FA and FA-like proteins are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 3.

FA genetic subtypes

| Complementation group (gene) | Approximate % of patients with FA | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | ||||

| A (FANCA) | 65 | 16q24.3 | FANCA | 44 |

| C (FANCC) | 12 | 9q22.32 | FANCC | 22 |

| G (FANCG) | 12 | 9p13.3 | FANCG/XRCC9 | 14 |

| J (FANCJ) | <5 | 17q23.2 | FANCJ/BRIP1 | 25 |

| E (FANCE) | 4 | 6p21.31 | FANCE | 10 |

| F (FANCF) | 4 | 11p14.3 | FANCF | 1 |

| P (FANCP) | 2 | 16p13.3 | FANCP/SLX4 | 17 |

| D1 (FANCD1) | <1 | 13q13.1 | FANCD1/BRCA2 | 27 |

| D2 (FANCD2) | <1 | 3p25.3 | FANCD2 | 45 |

| I (FANCI) | <1 | 15q26.1 | FANCI | 38 |

| L (FANCL) | <1 | 2p16.1 | FANCL | 14 |

| M (FANCM)* | <1 | 14q21.2 | FANCM | 25 |

| N (FANCN) | <1 | 16p12.2 | FANCN/PALB2 | 14 |

| O (FANCO)* | <1 | 17q22 | FANCO/RAD51C | 12 |

| Q (FANCQ) | <1 | 16p13.12 | FANCQ/ERCC4 | 13 |

| S (FANCS)* | <1 | 17q21.31 | FANCS/BRCA1 | 24 |

| T (FANCT) | <1 | 1q32.1 | FANCT/UBE2T | 7 |

| U (FANCU) | <1 | 7q36.1 | FANCU/XRCC2 | 3 |

| V (FANCV) | <1 | 1p36.22 | FANCV/REV7 | 10 |

| W (FANCW) | <1 | 16q23.1 | FANCW/RFWD3 | 18 |

| X-linked recessive | ||||

| B (FANCB) | <1 | Xp22.2 | FANCB | 17 |

| AD | ||||

| R (FANCR)* | <1 | 15q15.1 | FANCR/RAD51 | 13 |

FA subtypes (complementation groups) A, C, and G account for most patients with FA. As can be noted from the table, many FA genes encode proteins that had previously been known by other names and have important roles in DNA repair.

Biallelic variants in FANCM, FANCO, and FANCS and heterozygous variants in FANCR/RAD51 produce FA-like disease3 (abnormalities overlap with those in patients with FA but are not sufficient to be classified as bona fide FA).

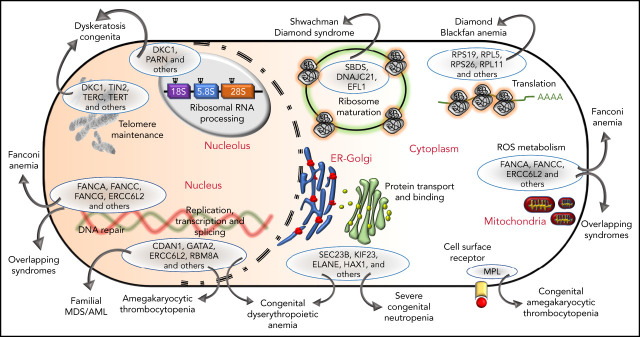

Figure 1.

Diverse molecular functions of the FA pathway. DNA repair in the FA pathway predominantly restores DNA interstrand cross-links to ensure bona fide replication and transcription. However, this activity is also involved in the resolution of DNA: RNA hybrids known as R-loops occurring predominantly in the nucleolus due to ribosomal DNA transcription by RNA polymerase 1 (RNAP1). R-loop resolution by FANCM, FANCI, and FANCD2 proteins ensures ribosome biogenesis. FANC proteins also clear mitochondria damaged by excessive reactive oxygen species and, in conjunction with PARKIN, execute mitophagy. Ub, ubiquitin modification; FAAP100, FA core complex–associated protein 100.

Dyskeratosis congenita

Classic dyskeratosis congenita (DC), first described in 1910, is an inherited BMF syndrome characterized by the mucocutaneous triad of abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and mucosal leucoplakia.26,27 These features frequently develop in children. Various other abnormalities have also been reported: dental (eg, severe caries), gastrointestinal (eg, esophageal stenosis), genitourinary (eg, phimosis), neurological (eg, cerebellar hypoplasia)], ophthalmic (eg, nasolacrimal duct narrowing), pulmonary (eg, pulmonary fibrosis), skeletal (eg, osteoporosis), and vascular; Table 2).27,28 BMF is a major cause of mortality, and DC predisposes patients to cancer and pulmonary complications. X-linked recessive, autosomal dominant (AD), and AR subtypes of DC are recognized. Sixteen DC genes (DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOP10, NHP2, TINF2, TCAB1, USB1, CTC1, RTEL1, ACD, PARN, NAF1, ZCCHC8, NPM1, and MDM4)29-43 have been identified (Table 4).

Table 4.

DC genetic subtypes

| DC Subtype | Approximate % of patients with DC | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-linked recessive | 25 | Xq28 | DKC1 (dyskerin) 15 | |

| Autosomal dominant | 12 | 14q12 | TIN2 | 6 |

| 5 | 3q26.2 | TERC* | 1 | |

| 3 | 5p15.33 | TERT* | 16 | |

| <1 | 4q32.2 | NAF1* | 13 | |

| <1 | 12q24.31 | ZCCHC8* | 17 | |

| <1 | 5q35.1 | NPM1 | 13 | |

| <1 | 1q32.1 | MDM4 | 13 | |

| Autosomal recessive | 2 | 16q21 | USB1 | 9 |

| 2 | 20q13.3 | RTEL1* | 35 | |

| 1 | 16p13.12 | PARN* | 27 | |

| <1 | 15q14 | NOP10 | 2 | |

| <1 | 5p15.33 | TERT* | 16 | |

| <1 | 5q35.3 | NHP2 | 4 | |

| <1 | 17p13.1 | WRAP5313 | ||

| <1 | 17p13.1 | CTC1 | 23 | |

| <1 | 16q22.1 | ACD/TPP1 | 13 | |

| Uncharacterized | >30 | ? | ? | ? |

The major subtypes of DC are associated with variants in DKC1, TINF2, TERC, and TERT.

Heterozygous variants in these genes have been associated with pulmonary disease in late adulthood. Most of the DC genes encode products that have a principal role in telomere maintenance; however, this is not the case for USB1 and NPM1. Variants in some other genes (GRHL2, DNAJC3, RECQL4, and LIG4) can produce features that overlap with DC.

The gene mutated in X-linked DC (DKC1) was identified in 1998. It encodes a highly conserved nucleolar protein called dyskerin. Dyskerin associates with the H/ACA class of small nucleolar RNAs in small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein particles, which are important in guiding the conversion of uridine to pseudouridine during ribosomal RNA maturation (Figure 2). Dyskerin also associates with the RNA component of telomerase (TERC), where it stabilizes the telomerase complex, which is critical for telomere maintenance44,45 (Figure 2). Heterozygous variants in TERC and TERT have been identified in patients with AD-DC30-32 and in some patients with aplastic anemia (AA), MDS, acute leukemia, and pulmonary and liver fibrosis.46-51 A subset of patients with the multisystem disorder Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome has DKC1 variants.52 Also, AR-DC is genetically heterogeneous with 9 subtypes because of biallelic variants in NHP2, NOP10, TERT, TCAB1, USB1, CTC1, RTEL1, ACD, and PARN. One AD-DC subtype is related to variants in TINF2, which encodes a component of the shelterin complex that protects telomeres and controls access of telomerase to a telomere. Subsequently, heterozygous variants in other genes (RTEL1, PARN, NAF1, ZCCHC8, NPM1, and MDM4) have been associated with some DC features.38-43 Collectively, these observations have demonstrated that classic DC, Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson, and a subset of AA and MDS/acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) are principally related to a defect in telomere maintenance, and cells from these patients have very short and/or abnormal telomeres.44,53 The multisystem abnormalities in these patients, including predisposition to cancer, have highlighted the critical role of telomeres and led to the recognition of a new category of human diseases called telomeropathies. Still, in different DC subtypes, the pathophysiology also includes nontelomere defects (Figure 2). For example, patients with DKC1, NHP2, and PARN variants also have ribosomal defects (Figure 2). The overall phenotype in any patient is therefore a summation of these different biological defects, environmental effects (eg, increased smoking-related risk of pulmonary complications), and age (eg, worsening of mucocutaneous features with aging). In addition, the clinical phenotype is influenced by the anticipation phenomenon, increasing disease severity in succeeding generations because of the inheritance of short telomeres through the germline. Collectively, these interacting factors make prognostic predictions and genetic counseling challenging.

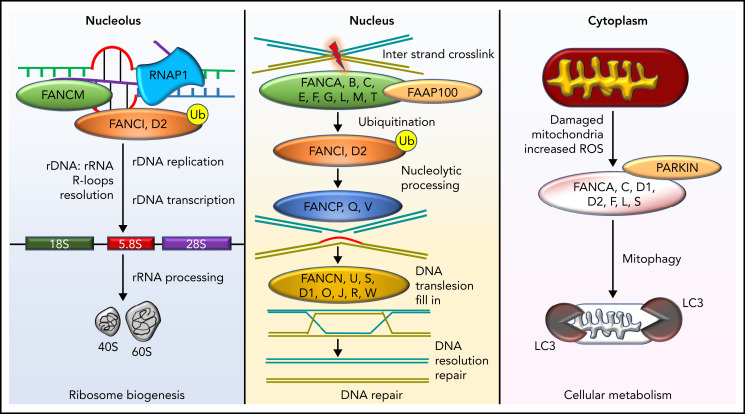

Figure 2.

Functional overlap of DC genes involved in telomere maintenance and ribosome biogenesis. Proteins mutated in DC are indicated by named capsules and affect molecular functions, such as telomere replication (RTEL1), telomere protection (TIN2, ACD), telomerase (TERC, TERT, and DKC1), and telomerase maturation and stability (ZCCHC8, NAF1, PARN, DKC1, NOP10, and NHP2). Pseudouridylation of TERC and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is performed by DKC1. The deadenylation function of PARN also regulates the maturation and processing of both TERC and rRNA. Recently, variants in NPM1 that regulate 2'O rRNA methylation have been reported in patients with DC. USB1 is an outlier, being involved in U6 spliceosomal RNA processing. Dashed arrows link different proteins to specific functions in which they are involved.

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS), first described in 1964, is usually an AR disorder characterized by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, BMF, and extrahematopoietic abnormalities, particularly metaphyseal dysostosis (Table 2).54,55 Pancreatic insufficiency becomes apparent early in infancy. Hematological abnormalities include neutropenia, AA (∼20%), MDS, and leukemia (∼25%). Most patients with SDS (>90%) have biallelic variants in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene56 (Table 5). The SBDS gene product has an important role in 60S ribosomal subunit maturation and, therefore, in ribosome biogenesis.57 Thus, SDS is principally a disorder of defective ribosome biogenesis.

Table 5.

SDS genetic subtypes

| SDS Subtype | Approximate % of patients with SDS | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | ||||

| Autosomal recessive | >90 | 7q11.21 | SBDS | 5 |

| SDS-like | ||||

| Autosomal recessive | <2 | 5p13.2 | DNAJC21 | 14 |

| <2 | 15q25.2 | EFL1 | 22 | |

| Autosomal dominant | ||||

| <2 | 14q13.2 | SRP54 | 17 |

Recently, it has been observed that biallelic variants in the EFL1 and DNAJC21 genes and heterozygous variants in the SRP54 gene can produce an SDS-like disease.57 Like SBDS, these proteins are also involved in ribosome biogenesis.

Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA), first described in 1934,58 usually presents in early infancy with features of anemia.59 The hallmark of classic DBA is a selective decrease in erythroid precursors and normochromic macrocytic anemia associated with various extrahematopoietic abnormalities, such as craniofacial (eg, high arched palate), thumb, cardiac, and urogenital malformations (Table 2). MDS and AML have been reported in a few patients with DBA, suggesting an increased predisposition to cancer. There are also cases that have evolved into AA. Thus, although DBA is typically regarded as pure red cell aplasia, a global hematopoietic defect can be observed in some patients.

The first DBA gene (RPS19) was identified in 1999,60 and it accounts for ∼25% of patients with DBA in White populations. Subsequently, heterozygous variants of other genes encoding small (RPS7, RPS10, RPS15, RPS17, RPS24, RPS26, RPS27, RPS28, and RPS29) and large (RPL5, RPL9, RPL11, RPL15, RPL18, RPL26, RPL27, RPL31, RPL35, and RPL35A) ribosomal subunits proteins have been reported (Table 6). Collectively, the genetic basis in ∼75% of patients with DBA can now be established.61-68 These observations have also demonstrated that DBA is a ribosome biogenesis disorder.

Table 6.

DBA genetic subtypes

| DBA subtype | Approximate % of patients with DBA | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant | 25 | 19q13.2 | RPS19 | 6 |

| 10-20 | Various* | — | — | |

| 7 | 1p22.1 | RPL5 | 8 | |

| 7 | 12q13.2 | RPS26 | 4 | |

| 5 | 1p36.11 | RPL11 | 6 | |

| 3 | 3q29 | RPL35A | 5 | |

| 3 | 6q21.31 | RPS10 | 6 | |

| 2.4 | 10q22.3 | RPS24 | 9 | |

| 1 | 15q25.2 | RPS17 | 6 | |

| <1 | 3p24.2 | RPL15 | 5 | |

| <1 | 2p25.3 | RPS7 | 7 | |

| <1 | 19p13.2 | RPS28 | 4 | |

| <1 | 14q21.3 | RPS29 | 5 | |

| <1 | 17p13.1 | RPL26 | 4 | |

| <1 | 19p13.3 | RPS15 | 4 | |

| <1 | 1q21.3 | RPS27 | 4 | |

| <1 | 4p14 | RPL9 | 8 | |

| <1 | 19q13.33 | RPL18 | 7 | |

| <1 | 17q21.31 | RPL27 | 6 | |

| <1 | 2q11.2 | RPL31 | 5 | |

| X-linked recessive | <1 | Xp11.23 | GATA1 | 6 |

| <1 | Xp11.22 | TSR2 | 5 | |

| Uncharacterized | ∼25 | ? | ? | ? |

Refers to large deletions in different DBA genes. Variants in EPO and CECR1/DADA2 can also produce DBA-like disease.

Some genotype-phenotype correlations have emerged. For example, patients with variants in RPL5 gene tend to have multiple physical abnormalities, including craniofacial, thumb, and heart anomalies, whereas isolated thumb malformations predominantly occur in patients with heterozygous RPL11 variants. A subgroup of patients with DBA/DBA-like disease has been associated with variants in GATA1 (encoding an erythroid transcriptional factor), CECR1/DADA2, TSR2, and EPO.68,69

In the Japanese population, RPS19 variants account only for ∼13% of patients with DBA, and there are also differences in the clinical phenotypes associated with different DBA genes compared with White populations. This result suggests ethnic differences in phenotypic expression, a feature that has been observed in other genetic diseases, including FA.

Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias

Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias (CDAs) comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by anemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, and morphological evidence of dyserythropoeisis.70,71 The first description of CDAs was published in 1966 by Crookston and colleagues.72 In 1968, Heimpel and Wendt73 classified CDAs into 3 types (I-III). Over the years, additional subtypes (IV-VII) have been added, often based on case reports.

Most patients with CDAI present with splenomegaly and anemia. In some patients, nonhematological features (eg, skeletal abnormalities) have been observed (Table 2). Ineffective erythropoiesis is evidenced by peripheral (anisocytosis) and BM (megaloblastic erythroid precursors, internuclear chromatin bridging, and binocularity affecting 3% to 7% of the erythroblasts) abnormalities and increased hemolysis markers. The defining feature is a “Swiss cheese” heterochromatin appearance in erythroblasts on electron microscopy. The first disease gene (CDAN1) was identified in 200274 (Table 7). Subsequently, CDIN1 (CDAN1 interacting nuclease 1) was found to be responsible for some CDAI cases.75

Table 7.

CDA genetic subtypes

| CDA Subtype | Approximate % of patients with CDA | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (AR) | Major subset | 15q15.2 | CDAN1 | 28 |

| Minor subset | 15q14 | CDIN1 | 18 | |

| Type II (AR) | Major subset | 20p11.23 | SEC23B | 22 |

| Type III (AD) | Rare | 15q23 | KIF23 | 25 |

| Other subtypes | ? | 19p13.13 | KLF1 | 3 |

CDAII is the most common CDA subtype and was described as hereditary erythroblastic multinuclearity with a positive acidified serum lysis test (HEMPAS) in 1969.76 It is inherited as an AR trait. The anemia is variable (80-110 g/L), and ∼10% of cases require regular blood transfusions. Clinical presentations include a variable degree of jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and liver cirrhosis. Peripheral blood morphology shows anisocytosis, and BM features include normoblastic erythroid hyperplasia with usually more than 10% binucleate erythroblasts. On electron microscopy, erythroid cells have a characteristic endoplasmic reticulum arrangement that gives them a double-membrane appearance. Red cells are hemolyzed by acidified sera, but not by the patient’s own serum. In 2009, the gene encoding the secretory coat protein complex II component SEC23B has been shown to be responsible for CDAII.77

CDAIII is rare. In one of the largest (Swedish) families investigated, the disease was characterized by giant multinucleated erythroblasts. CDAIII exhibits AD inheritance and is caused by variants in KIF23.78 KIF23 encodes mitotic kinesin-like protein 1, which has a critical role in cytokinesis during cell division.

The precise role of the proteins encoded by CDAN1, CDINI, and SEC23B in disease pathology remains unknown. CDA-like disease related to variants in erythroid transcription factor genes (GATA1 and KLF1)79 have also been identified.

Severe congenital neutropenia

Severe congenital neutropenia (SCN), including Kostmann syndrome, is characterized by severe peripheral neutropenia (<0.2 × 109/L).80,81 These patients present with recurrent life-threatening infections in infancy. BM examination frequently shows maturation arrest in the myeloid lineage, and some patients can present with cyclical neutropenia. These patients can progress to MDS and leukemia, usually with an acquisition of secondary mutations in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) receptor. In most patients, heterozygous variants in the neutrophil elastase gene (ELANE) have been identified.82 These variants are thought to cause an accumulation of a nonfunctional protein, which, in turn, triggers an unfolded protein response, leading to a maturational arrest. The original family described by Kostmann had AR-SCN and was caused by biallelic variants in HAX1, 83 predicted to result in cell death defects. Variants in other genes (GFI1, G6PC3, CSF3R, JAGN1, and VPS45)84-86 have also been associated with SCN (Table 8). Whereas ELANE variants typically produce isolated neutropenia, variants in some other genes are associated with extrahematological abnormalities. There are also several syndromes (reviewed by Hauck and Klein81) that involve neutropenia as part of a broader syndrome.

Table 8.

SCN genetic subtypes

| Subtype | Approximate % of patients with SCN | Chromosome location | Gene product | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant | 50-60 | 19p13.3 | ELANE | 6 |

| <2 | 1p22.1 | GFI1 | 11 | |

| Autosomal recessive | 15 | 1q21.3 | HAX1 | 7 |

| 5 | 17q21.31 | G6PC3 | 8 | |

| Rare | 1q21.2 | VPS45 | 18 | |

| Rare | 1p34.3 | CSF3R | 19 | |

| ? | 3p25.3 | JAGN1 | 2 | |

| Miscellaneous syndromes* | — | — | — | — |

A heterogeneous group that includes patients with neutropenia as part of a broader syndrome. Some of the genes and associated syndromes in this category are WAS (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein), SBDS (Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome), G6PC (glycogen storage disease), CXCR4 (WHIM syndrome), TAZ (Barth syndrome), RBSN (syndromic myelofibrosis and neutropenia), and SMARCD2.

Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and other syndromic thrombocytopenias

Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT) usually presents in infancy and is characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia and a reduction or absence of megakaryocytes in the BM, usually without extrahematopoietic abnormalities. Approximately 50% of patients develop AA by the age of 5 years. The disease can evolve into MDS or leukemia. Patients with CAMT have biallelic variants in the gene (MPL) encoding thrombopoietin receptor (Table 9).87

Table 9.

CAMT, syndromic thrombocytopenia, and other syndromic thrombocytopenias

| Subtype | Approximate % of patients | Chromosome location | Gene product/locus | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMT | ||||

| Autosomal recessive | Majority | 1p34.2 | MPL | 11 |

| TAR Autosomal recessive |

Majority | 1q21.1 | RBM8A | 6 |

| Radioulnar synostosis | ? | 7p15.2 3q26.2 | HOXA11 | 2 23 |

| Autosomal dominant | — | — | MECOM* | — |

MECOM (MDS1 and EVI1 Complex Locus) variants can be associated with variable hematological features ranging from isolated thrombocytopenia to global BM failure and leukemia.

Thrombocytopenia with absent radius (TAR) is usually diagnosed in infancy. TAR is caused by the compound inheritance of a low-frequency, noncoding, single-nucleotide polymorphism and a rare null allele in RMB8A. Thrombocytopenia associated with proximal radius and ulna fusion is a relatively new entity arising from heterozygous variants in HOXA11 or MECOM. Although patients typically have thrombocytopenia, those with MECOM variants can exhibit very variable hematological phenotypes, including progression to MDS and leukemia.88 Furthermore, some MECOM variants have been associated with hematological abnormalities, including global BMF in infancy, but no radioulnar fusion.89

New subtypes of inherited BMF and overlapping syndromes

There are familial BMF cases and/or those that have ≥1 extrahematopoietic abnormalities but do not fit into the entities discussed herein thus far. The availability of next-generation sequencing has enabled elucidation of the genetic basis of some of these disorders. Examples of these new entities include those associated with germline variants (Table 10) in TPO, ERCC6L2, MYSM1, DUT, EXOC3L2, TP53, and SP189,90 and the number of cases reported in each subtype varies.

There are also entities that are initially characterized in patients with MDS/leukemia or other syndromic diseases, but can also present with peripheral cytopenias. These entities include GATA2 deficiency and SAMD9/SAMD9L-related disease. In addition to MDS and leukemia, these patients can have a variable number of extrahematopoietic abnormalities. Germline variants in these genes are particularly prevalent in pediatric patients with MDS associated with monosomy 7. GATA2 and SAMD9/SAMD9L are also included in the category of familial MDS/AML genes.91 Other genes in this category include RUNX1, CEBPA, TERC, TERT, SRP72, AKNRD26, ETV6, DDX41, RTEL1, PAX5, TP53, ACD, MECOM, HLTF, XPC, and DHX34 (Table 10). This highlights the overlapping nature of hematological (BMF, MDS, and AML) and extrahematological phenotypes produced by germline variants in the mentioned genes. It is likely that additional new entities of familial BMF/MDS will be characterized in the future.

Epidemiology

The true incidence and natural history of inherited BMF disorders remain uncertain. SCN and DBA are among the most prevalent of these disorders; for example, the estimated annual DBA birth incidence is 5 per 106. Tamary et al reported on a retrospective population-based registry of inherited BMF syndromes in Israel,92 representing the first comprehensive population-based study to evaluate the incidence and complications of the different inherited BMF syndromes. A total of 127 patients diagnosed from 1966 through 2007 were registered: 52% had FA, 17% had SCN, 14% had DBA, 6% had CAMT, 5% had DC, 2% had SDS, and 2% had TAR. The most common disease was FA, which also carried the worst prognosis, with severe BMF and development of cancer. These data are probably relevant only to Israel. For example, based on the data from this registry, the annual FA incidence was calculated to be ∼2 per 100 000 live births, sevenfold higher than expected from the worldwide carrier frequency of 1 in 300 and probably reflecting a high consanguinity rate in Israel.

In a subsequent report from the Canadian registry,93 the most common disease was DBA followed by FA, showing an FA incidence of ∼11.4 cases per 106 births. It is likely that the true incidence/prevalence of these disorders varies in different regions of the world, reflecting such factors as consanguinity rates and environmental influences, such as infections. This variation has also been reported in a recent study by Bluteau et al from France.89 Further studies on the epidemiology of these disorders are desirable.

General principles of diagnosis and management

A diagnosis of an inherited BMF should be considered in a pediatric patient when ≥1 BMF-associated extrahematopoietic features are identified clinically or by investigations. It should also be considered during differential diagnosis in children presenting with isolated AA, MDS, or leukemia. The specific extrahematopoietic abnormalities help diagnose a recognized syndrome, but this diagnosis is not always possible based on clinical features alone.

Chromosomal breakage analysis of blood lymphocytes after exposure to DEB or MMC remains a useful diagnostic test for FA. However, it may give unclear results if there is somatic mosaicism, and biallelic variants in the Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene can also cause increased chromosomal breakage with MMC or DEB. All children presenting with AA and MDS ideally should be tested for FA. Furthermore, children who present with leukemia and suggestive congenital abnormalities or who have monosomy 7, an additional chromosome 3, or complex karyotypes should be tested for FA. Genetic testing for FA genes is possible but not always straightforward. Telomere length, particularly using flow fluorescence in situ hybridization, can be a useful initial screening test in the diagnosis of DC or DC-like disease.94 Patients with DC frequently, but not always, have chromosomes with very short telomeres. Genetic testing for DC genes can help substantiate the diagnosis. However, as in FA, this strategy is not straightforward, as many patients have certain variants that can be difficult to categorize, and the genetic basis will remain unknown even though approximately one-third of patients have been tested for currently known DC genes. In patients with global BMF, the other genes to consider are SDS genes and new entities, such as those, mentioned herein, including variants in TPO, ERCC6L2, MYSM1, MECOM, and SAMD9/SAMD9L. For patients presenting with isolated neutropenia, analysis of ELANE and HAX1 may help substantiate the underlying diagnosis. For those with isolated anemia, an initial focus on DBA and CDA genes is warranted.

Because of the availability of next-generation sequencing, many clinicians now have access to targeted gene panels that can test for all BMF genes (>100) simultaneously (Tables 3-10). Furthermore, there is increasing access to whole-exome and whole-genome analyses. Similar to all tests, these approaches have advantages and disadvantages. For example, if a new variant(s) is identified even in a known disease gene, it is not always possible to be certain that the variant is responsible for the clinical phenotype. In such cases, studies of the segregation of the variant within families and functional analyses can provide useful additional information on the significance of the variant.

Once an inherited BMF diagnosis has been made, clinically and/or genetically, the chronic nature of these disorders should be explained to the patient and family. In general, patients need lifetime follow-up (ideally, in a special BMF clinic) and will need monitoring for hematological complications, including leukemia, immunological defects, and cancer. The frequency of monitoring investigations, such as blood tests, BM examinations, and pulmonary function tests, is difficult to precisely stipulate because of the considerable heterogeneity and the absence of randomized studies. However, regular follow-up is advisable, possibly annually, with more frequent monitoring being implemented as specific problems arise. Expert groups have developed consensus guidelines95 that provide a useful framework for clinical practice.

Owing to the significant risk of cancer in many of these syndromes, particularly as patients enter adulthood, avoidance of smoking is advisable. They should also avoid sunbathing and minimize alcohol intake as they enter adulthood. Patients should be regularly screened for hematological and nonhematological cancer.95 Treatment for cancer depends on the specific type, but the underlying genetic defect should be considered (ie, more supportive care and reduced drug doses).

Regarding pulmonary disease, patients should avoid smoking, particularly those with FA or DC. Medical treatment is usually difficult in severe lung disease, and lung transplant may be an option in some cases. Advice on skincare (eg, use of moisturizing creams) and sunlight avoidance are important. They should also avoid occupations that expose them to hazardous chemicals or repeated physical trauma. When doing domestic chores, such as cleaning, protective gloves should be used, particularly in DC. Avoiding extremes of temperature is desirable, as the skin is usually fragile compared with that in the normal population. Liver disease is more common in patients with FA or DC than in the population without these disorders; hence, all administered drugs require close monitoring. Drugs also should be used carefully, as patients with inherited BMF syndromes tend to be small and more sensitive to many drugs. This factor is particularly important in patients with FA or DC who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT).

Management of hematological complications

Major advances in supportive treatment have led to considerable improvements in the outcome of these patients. Red cell transfusions should be performed to maintain the hemoglobin at an asymptomatic level (typically, >80 g/L), and platelets should be maintained at >10 × 109/L. All patients with neutropenia must receive prompt therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics if they develop an infection. Addition of G-CSF may be appropriate in these circumstances. Leukocyte-depleted and, where appropriate, cytomegalovirus-negative blood products should be chosen, to prevent the development of HLA antibodies and reduce the risk of cytomegalovirus.

Inherited BMF syndromes usually respond to specific interventions. In patients with FA and DC who have significant peripheral cytopenias (hemoglobin <80 g/L, neutrophils <0.5 × 09/L, and platelets <20 × 109/L), the first-line medical therapy in some countries is frequently oxymetholone started at 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg per day and gradually increased, if necessary, to a maximum dose of 5 mg/kg per day. Patients with DC are usually more sensitive to oxymetholone than are patients with FA. There is also increasing experience in danazol use in these patients, and now, danazol is preferably used compared with oxymetholone.96,97 Approximately 70% of patients with DC or FA will have a hematological response to danazol that can be durable for years in some patients. Patients with severe BMF and HLA-compatible donors can be cured of their hematological complications by SCT. In patients with severe BMF without significant comorbidities, it is reasonable to consider upfront SCT without prior androgen therapy. If family donors are to be used, ensuring that they have been adequately tested for the relevant genetic variant(s) is important. It has been established that patients with inherited BMF syndromes have greater efficacy and lower toxicity with low-intensity, fludarabine-based protocols. There is now considerable experience using such protocols in patients with FA or DC, but this is not the case with some rare entities.98-102 The use of cord blood and haploidentical donors is also beneficial in specific circumstances. After many challenges, there has been some recent success with hematopoietic gene therapy in patients with FA subtype A.103 In the future, therapeutic strategies that target disease-specific hematopoietic stem cell defects are likely to emerge. There have been exciting preclinical studies on the role of transforming growth factor-β inhibitors in FA104 and PAPD5, a human poly(A) polymerase, inhibitors in DC.105

In patients with DBA, the first-line therapy remains prednisolone, as up to 80% of patients respond to this treatment. Prednisolone dose and frequency are titrated to the lowest number required to maintain reasonable hemoglobin and minimize side effects. In the minority of steroid-refractory patients or those who become refractory to prednisolone, treatment with regular blood transfusions is instituted and should be accompanied by a comprehensive iron-chelating program to prevent iron overload. At this stage, hematopoietic SCT may be appropriate and potentially curative for patients with DBA who have compatible sibling BM donors. The current emerging consensus is to recommend SCT before the age of 10 years (ideally, before 5 years) in every child requiring transfusion support with either a sibling or a fully matched, unrelated donor.106

Patients with CDA with mild anemia require no major interventions. Folate supplementation is prescribed to prevent folate deficiency. If regular transfusions are necessary, early attention to iron chelation is essential. Iron loading may also occur in nontransfused patients with CDA. Splenectomy may be beneficial in some patients (CDAII), and there are reports of successful hematopoietic SCT.70,107 In CDAI, there are also case reports of improvement after treatment with interferon-α.70 The mechanism of this therapeutic benefit remains unclear.

The mainstay of neutropenia management in patients with SCN is G-CSF. More than 90% of patients respond to this treatment, and the dose is adjusted to maintain an absolute neutrophil count of 1.5 to 2.0 × 109/L. Other measures to prevent infection are also instituted, and any evidence of infection should be promptly treated. For patients with compatible donors, SCT may be appropriate if they have a poor response to G-CSF or there is evolution to MDS/leukemia.108

Concluding remarks

The major advances in the molecular basis of inherited BMF syndromes have provided insights into critical biological pathways, such as DNA repair (FA), telomere maintenance (DC), and ribosome biogenesis (SDS and DBA). They have also provided interesting links between inherited (eg, DBA and SDS) and acquired (eg, MDS and 5q− syndrome) hematological disorders.

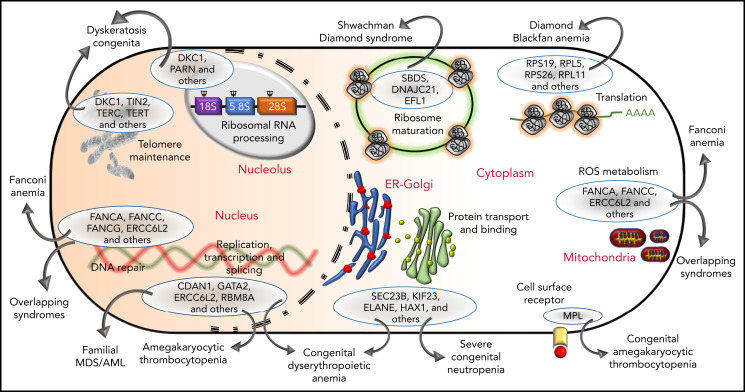

Phenotypic similarities (BMF, extrahematopoietic abnormalities, and cancer) between these syndromes have been acknowledged for years (Tables 1 and 2). Not surprisingly, the overlap is also observed at the level of molecular pathology (Figure 3). For example, SDS and DBA are both disorders of ribosomal biogenesis, whereas FA, DC, and SDS all have short telomeres. Further overlapping and biological connections may emerge in the future.

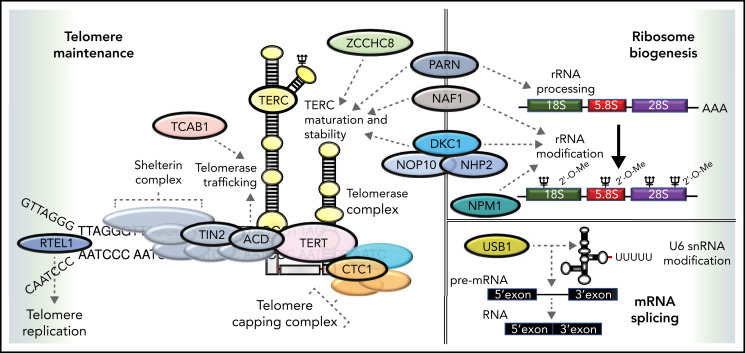

Figure 3.

The genetic, subcellular, and molecular landscape of inherited BMF syndromes. The predominant molecular functions of the genes involved in the inherited BMF syndromes are illustrated in a cell diagram. The most clinically significant genes involved in the pathways are shown within the blue ellipses; for full listings of other genes, please refer to Tables 3-10. Outward-pointing arrows indicate different clinical subtypes and overlapping syndromes, as discussed in the text, which are caused by defects in the molecular pathways.

In clinical practice, significant genetic advances have led to improved diagnosis, particularly for those with atypical presentations, and have enabled better personalized management. This includes the use of low-intensity, fludarabine-based conditioning protocols that have resulted in improvements in outcomes after hematopoietic SCT and the repurposing of drugs such as danazol. New therapies capable of correcting or ameliorating disease-specific defects of different syndromes are emerging in the laboratory setting, with potential for translation into the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our current (Jenna Alnajar, Jude Fitzgibbon, Upal Hossain, Nikolas Pontikos, Ana Rio-Machin, and Amanda Walne) and past (Richard Beswick, Shirleny Cardosa, Laura Collopy, Alicia Ellison, Michael Kirwan, Stuart Knight, Anna Marrone, Philip Mason, Jasmin Sidhu, and David Stevens) colleagues, whose contribution has been important to our research program over the years and the patients and colleagues (doctors, nurses, and all other staff) for their support.

This work was supported by the The Wellcome Trust, Blood Cancer UK, and Medical Research Council.

Authorship

Contribution: I.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and it was revised by H.T. and T.V.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Inderjeet Dokal, Centre for Genomics and Child Health, Blizard Institute, 4 Newark St, E1 2AT, United Kingdom; e-mail: i.dokal@qmul.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shimamura A, Alter BP. Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev. 2010;24(3):101-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanconi G. Familiare infantile pernziosaartige anaemie (pernizioses Blutbild und Konstitution). Jahrb Kinderh. 1927;117:257-280. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogliolo M, Surrallés J. Fanconi anemia: a model disease for studies on human genetics and advanced therapeutics. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;33:32-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strathdee CA, Gavish H, Shannon WR, Buchwald M. Cloning of cDNAs for Fanconi’s anaemia by functional complementation [published correction appears in Nature. 1992;358(6385):434]. Nature. 1992;356(6372):763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo Ten Foe JR, Rooimans MA, Bosnoyan-Collins L, et al. Expression cloning of a cDNA for the major Fanconi anaemia gene, FAA [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 1996 Dec;14(4):488]. Nat Genet. 1996;14(3):320-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Winter JP, Waisfisz Q, Rooimans MA, et al. The Fanconi anaemia group G gene FANCG is identical with XRCC9. Nat Genet. 1998;20(3):281-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Winter JP, Léveillé F, van Berkel CG, et al. Isolation of a cDNA representing the Fanconi anemia complementation group E gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(5):1306-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Winter JP, Rooimans MA, van Der Weel L, et al. The Fanconi anaemia gene FANCF encodes a novel protein with homology to ROM. Nat Genet. 2000;24(1):15-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmers C, Taniguchi T, Hejna J, et al. Positional cloning of a novel Fanconi anemia gene, FANCD2. Mol Cell. 2001;7(2):241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlett NG, Taniguchi T, Olson S, et al. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in Fanconi anemia. Science. 2002;297(5581):606-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meetei AR, Levitus M, Xue Y, et al. X-linked inheritance of Fanconi anemia complementation group B. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1219-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitus M, Waisfisz Q, Godthelp BC, et al. The DNA helicase BRIP1 is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group J. Nat Genet. 2005;37(9):934-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, et al. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):162-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, et al. Identification of the FANCI protein, a monoubiquitinated FANCD2 paralog required for DNA repair. Cell. 2007;129(2):289-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaz F, Hanenberg H, Schuster B, et al. Mutation of the RAD51C gene in a Fanconi anemia-like disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):406-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoepker C, Hain K, Schuster B, et al. SLX4, a coordinator of structure-specific endonucleases, is mutated in a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Nat Genet. 2011;43(2): 138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogliolo M, Schuster B, Stoepker C, et al. Mutations in ERCC4, encoding the DNA-repair endonuclease XPF, cause Fanconi anemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(5):800-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hira A, Yoshida K, Sato K, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the E2 conjugating enzyme UBE2T cause Fanconi anemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(6):1001-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bluteau D, Masliah-Planchon J, Clairmont C, et al. Biallelic inactivation of REV7 is associated with Fanconi anemia. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(3):1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knies K, Inano S, Ramírez MJ, et al. Biallelic mutations in the ubiquitin ligase RFWD3 cause Fanconi anemia. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):3013-3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(10):735-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crossan GP, Patel KJ. The Fanconi anaemia pathway orchestrates incisions at sites of crosslinked DNA. J Pathol. 2012;226(2):326-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garaycoechea JI, Crossan GP, Langevin F, et al. Alcohol and endogenous aldehydes damage chromosomes and mutate stem cells. Nature. 2018;553(7687):171-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dufour C, Corcione A, Svahn J, et al. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma are overexpressed in the bone marrow of Fanconi anemia patients and TNF-alpha suppresses erythropoiesis in vitro. Blood. 2003;102(6):2053-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sondalle SB, Longerich S, Ogawa LM, Sung P, Baserga SJ. Fanconi anemia protein FANCI functions in ribosome biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(7):2561-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zinsser F. Atrophia Cutis Reticularis cum Pigmentations, Dystrophia Unguium et Leukoplakis oris (Poikioodermia atrophicans vascularis Jacobi.). Ikonographia Dermatologica. 1910;5:219-223. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita in all its forms. Br J Haematol. 2000;110(4):768-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgs C, Crow YJ, Adams DM, et al. ; Clinical Care Consortium for Telomere-associated Ailments (CCCTAA) . Understanding the evolving phenotype of vascular complications in telomere biology disorders. Angiogenesis. 2019;22(1):95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Goldman F, et al. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001;413(6854):432-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armanios M, Chen JL, Chang YP, et al. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(44):15960-15964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrone A, Walne A, Tamary H, et al. Telomerase reverse-transcriptase homozygous mutations in autosomal recessive dyskeratosis congenita and Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome. Blood. 2007;110(13):4198-4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in autosomal recessive dyskeratosis congenita with one subtype due to mutations in the telomerase-associated protein NOP10. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(13):1619-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, et al. Mutations in the telomerase component NHP2 cause the premature ageing syndrome dyskeratosis congenita. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(23):8073-8078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage SA, Giri N, Baerlocher GM, Orr N, Lansdorp PM, Alter BP. TINF2, a component of the shelterin telomere protection complex, is mutated in dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(2):501-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Dokal I. Mutations in C16orf57 and normal-length telomeres unify a subset of patients with dyskeratosis congenita, poikiloderma with neutropenia and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(22):4453-4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong F, Savage SA, Shkreli M, et al. Disruption of telomerase trafficking by TCAB1 mutation causes dyskeratosis congenita. Genes Dev. 2011;25(1):11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Kirwan M, Plagnol V, Dokal I. Constitutional mutations in RTEL1 cause severe dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(3):448-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tummala H, Walne A, Collopy L, et al. Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease deficiency impacts telomere biology and causes dyskeratosis congenita. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):2151-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley SE, Gable DL, Wagner CL, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the RNA biogenesis factor NAF1 predispose to pulmonary fibrosis-emphysema. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(351):351ra107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gable DL, Gaysinskaya V, Atik CC, et al. ZCCHC8, the nuclear exosome targeting component, is mutated in familial pulmonary fibrosis and is required for telomerase RNA maturation. Genes Dev. 2019;33(19-20):1381-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nachmani D, Bothmer AH, Grisendi S, et al. Germline NPM1 mutations lead to altered rRNA 2′-O-methylation and cause dyskeratosis congenita. Nat Genet. 2019;51(10):1518-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toufektchan E, Lejour V, Durand R, et al. Germline mutation of MDM4, a major p53 regulator, in a familial syndrome of defective telomere maintenance. Sci Adv. 2020;6(15):eaay3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999;402(6761):551-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(10):640-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Dokal I, Mason PJ. Association between aplastic anaemia and mutations in telomerase RNA. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2168-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi H, Calado RT, Ly H, et al. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1413-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(13):1317-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calado RT, Regal JA, Kleiner DE, et al. A spectrum of severe familial liver disorders associate with telomerase mutations. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(4):1187-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(11):1567-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knight SW, Heiss NS, Vulliamy TJ, et al. Unexplained aplastic anaemia, immunodeficiency, and cerebellar hypoplasia (Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome) due to mutations in the dyskeratosis congenita gene, DKC1. Br J Haematol. 1999;107(2):335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vulliamy TJ, Knight SW, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Very short telomeres in the peripheral blood of patients with X-linked and autosomal dyskeratosis congenita. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001; 27:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shwachman H, Diamond LK, Oski FA, Khaw KT. The syndrome of pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction. J Pediatr. 1964;65(5):645-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dror Y, Freedman MH. Shwachman-diamond syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2002;118(3):701-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boocock GRB, Morrison JA, Popovic M, et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33(1):97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warren AJ. Molecular basis of the human ribosomopathy Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Adv Biol Regul. 2018;67:109-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Josephs HW. Anemia of infancy and early childhood. Medicine (Baltimore). 1936;15(3):307-451. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lipton JM, Atsidaftos E, Zyskind I, Vlachos A. Improving clinical care and elucidating the pathophysiology of Diamond Blackfan anemia: an update from the Diamond Blackfan Anemia Registry. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(5):558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Draptchinskaia N, Gustavsson P, Andersson B, et al. The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cmejla R, Cmejlova J, Handrkova H, Petrak J, Pospisilova D. Ribosomal protein S17 gene (RPS17) is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(12):1178-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gazda HT, Sheen MR, Vlachos Aet al. Ribosomal protein L5 and L11 mutations are associated with cleft palate and abnormal thumbs in Diamond-Blackfan anemia patients. J Hum Genet. 2008;83(6):769-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farrar JE, Nater M, Caywood E, et al. Abnormalities of the large ribosomal subunit protein, Rpl35a, in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Blood. 2008;112(5):1582-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choesmel V, Fribourg S, Aguissa-Touré AH, et al. Mutation of ribosomal protein RPS24 in Diamond-Blackfan anemia results in a ribosome biogenesis disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(9):1253-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doherty L, Sheen MR, Vlachos A, et al. Ribosomal protein genes RPS10 and RPS26 are commonly mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(2):222-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gazda HT, Preti M, Sheen MR, et al. Frameshift mutation in p53 regulator RPL26 is associated with multiple physical abnormalities and a specific pre-ribosomal RNA processing defect in diamond-blackfan anemia. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(7):1037-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Landowski M, O’Donohue MF, Buros C, et al. Novel deletion of RPL15 identified by array-comparative genomic hybridization in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Hum Genet. 2013;132(11):1265-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ulirsch JC, Verboon JM, Kazerounian S, et al. The Genetic landscape of Diamond-Blackfan anemia [published correction appears in Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(2):356]. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(6):930-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sankaran VG, Ghazvinian R, Do R, et al. Exome sequencing identifies GATA1 mutations resulting in Diamond-Blackfan anemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2439-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wickramasinghe SN, Wood WG. Advances in the understanding of the congenital dyserythropoietic anaemias. Br J Haematol. 2005;131(4):431-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iolascon A, Heimpel H, Wahlin A, Tamary H. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias: molecular insights and diagnostic approach. Blood. 2013;122(13):2162-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crookston JH, Godwin TF, Wightman KJR, et al. Congenital Dyserythropoietic Anaemia. Presented at the Eleventh Congress of the International Society of Haematology [abstract]. Sydney, Australia, 21-26 August 1966. 1966:18.

- 73.Heimpel H, Wendt F. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia with karyorrhexis and multinuclearity of erythroblasts. Helv Med Acta. 1968;34:103-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dgany O, Avidan N, Delaunay J, et al. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I is caused by mutations in codanin-1. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(6):1467-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Babbs C, Roberts NA, Sanchez-Pulido L, et al. ; WGS500 Consortium . Homozygous mutations in a predicted endonuclease are a novel cause of congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I. Haematologica. 2013;98(9):1383-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Crookston JH, Crookston MC, Burnie KL, et al. Hereditary erythroblastic multinuclearity associated with a positive acidified-serum test: a type of congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1969;17(1):11-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwarz K, Iolascon A, Verissimo F, et al. Mutations affecting the secretory COPII coat component SEC23B cause congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II. Nat Genet. 2009;41(8):936-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liljeholm M, Irvine AF, Vikberg AL, et al. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type III (CDA III) is caused by a mutation in kinesin family member, KIF23. Blood. 2013;121(23):4791-4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arnaud L, Saison C, Helias V, et al. A dominant mutation in the gene encoding the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 causes a congenital dyserythropoietic anemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(5):721-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Welte K, Zeidler C. Severe congenital neutropenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:307-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hauck F, Klein C. Pathogenic mechanisms and clinical implications of congenital neutropenia syndromes. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13(6):596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dale DC, Person RE, Bolyard AA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase in congenital and cyclic neutropenia. Blood. 2000;96(7):2317-2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klein C, Grudzien M, Appaswamy G, et al. HAX1 deficiency causes autosomal recessive severe congenital neutropenia (Kostmann disease). Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Person RE, Li FQ, Duan Z, et al. Mutations in proto-oncogene GFI1 cause human neutropenia and target ELA2. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):308-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boztug K, Appaswamy G, Ashikov A, et al. A syndrome with congenital neutropenia and mutations in G6PC3. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(1):32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vilboux T, Lev A, Malicdan MC, et al. A congenital neutrophil defect syndrome associated with mutations in VPS45. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):54-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ihara K, Ishii E, Eguchi M, et al. Identification of mutations in the c-mpl gene in congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(6):3132-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Walne A, Tummala H, Ellison A, et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genetic spectrum of radioulnar synostosis associated hematological disease. Haematologica. 2018;103(7):e284-e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bluteau O, Sebert M, Leblanc T, et al. A landscape of germ line mutations in a cohort of inherited bone marrow failure patients. Blood. 2018;131(7):717-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tummala H, Dokal AD, Walne A, et al. Genome instability is a consequence of transcription deficiency in bone marrow failure patients harboring biallelic ERCC6L2 variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:7777-7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rio-Machin A, Vulliamy T, Hug N, et al. The complex genetic landscape of familial MDS and AML reveals pathogenic germline variants. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tamary H, Nishri D, Yacobovich J, et al. Frequency and natural history of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes: the Israeli Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Registry. Haematologica. 2010;95(8):1300-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsangaris E, Klaassen R, Fernandez CV, et al. Genetic analysis of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes from one prospective, comprehensive and population-based cohort and identification of novel mutations. J Med Genet. 2011;48(9):618-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, et al. Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2007;110(5):1439-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ripperger T, Bielack SS, Borkhardt A, et al. Childhood cancer predisposition syndromes-A concise review and recommendations by the Cancer Predisposition Working Group of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(4):1017-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scheckenbach K, Morgan M, Filger-Brillinger J, et al. Treatment of the bone marrow failure in Fanconi anemia patients with danazol. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2012;48(2):128-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, Liu D, et al. Danazol treatment for telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1922-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.de la Fuente J, Reiss S, McCloy M, et al. Non-TBI stem cell transplantation protocol for Fanconi anaemia using HLA-compatible sibling and unrelated donors [published correction appears in Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004 Jul;34(1):95]. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(7):653-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ebens CL, MacMillan ML, Wagner JE. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in Fanconi anemia: current evidence, challenges and recommendations. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(1):81-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li Q, Luo C, Luo C, et al. Disease-specific hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(8):1389-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dietz AC, Orchard PJ, Baker KS, et al. Disease-specific hematopoietic cell transplantation: nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen for dyskeratosis congenita. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(1):98-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fioredda F, Iacobelli S, Korthof ET, et al. Outcome of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in dyskeratosis congenita. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(1):110-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Río P, Navarro S, Wang W, et al. Successful engraftment of gene-corrected hematopoietic stem cells in non-conditioned patients with Fanconi anemia. Nat Med. 2019;25(9):1396-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang H, Kozono DE, O’Connor KW, et al. TGF-P Inhibition rescues hematopoietic stem cell defects and bone marrow failure in Fanconi anemia. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(5):668-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nagpal N, Wang J, Zeng J, et al. Small-molecule PAPD5 inhibitors restore telomerase activity in patient stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(6):896-909.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fagioli F, Quarello P, Zecca M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Diamond Blackfan anaemia: a report from the Italian Association of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology Registry. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(5):673-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Miano M, Eikema DJ, Aljurf M, et al. Stem cell transplantation for congenital dyserythropoietic anemia: an analysis from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2019;104(8):e335-e339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fioredda F, Iacobelli S, van Biezen A, et al. ; Severe Aplastic Anemia the Inborn Error, and the Pediatric Disease Working Parties of the European Society for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and Stem Cell Transplant for Immunodeficiencies in Europe (SCETIDE) . Stem cell transplantation in severe congenital neutropenia: an analysis from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2015; 126(16):1885-1892, quiz 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.