Abstract

The control and inhibition of microbial infection are of critical importance for patients undergoing dental or orthopedic surgery. A critical requirement is the prevention of bacterial growth, subsequent bacterial colonization of implant surfaces, and biofilm formation. Among biofilm-forming bacteria, S. aureus and S. epidermidis are the most common bacteria responsible for causing implant-related infections. The ability to produce customized and patient-specific antimicrobial treatments will significantly reduce infections leading to enhanced patient recovery. We propose that 3D-printed antimicrobial biomedical devices for on-demand infection prophylaxis and disease prevention are a rational solution for the prevention of infection. In this study, we modified 3D printed polylactic acid (PLA) constructs using an alkali treatment to increase hydrophilicity and functionalized the surface of the constructs using a suspension of Zinc/HNTs-Ag-Chitosan Oligosaccharide Lactate (ZnHNTs-Ag-COS). The morphologies of printed constructs were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy-Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and chemical analysis by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Assessment of the antimicrobial potential of our constructs was assessed using agar diffusion and biofilm assays. The surface of 3D printed PLA constructs were chemically modified to increase hydrophilicity and suspensions of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag were adsorbed on the construct surface. Surface adsorption of ZnHNTs-Ag-COS on PLA printed constructs was determined to be a function of relative pore size. Morphological surface characterization using SEM-EDS confirmed the presence of the suspension coatings on the constructs, and FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag in the coatings. The inhibition of bacterial growth was evaluated using the agar diffusion method. Results obtained confirmed the antimicrobial potential of the PLA constructs (which was a function of the Ag content in the material).

Keywords: 3D printing, chitosan, functionalization, halloysite nanotubes, metal nanoparticles, antimicrobial, zinc, silver

Introduction

Invasive medical and prosthetic devices are used in treating millions of patients each day. The surfaces of these devices provide ideal environments where pathogens can attach and proliferate masked from the patient’s immune defenses[1]. A critical need is the prevention of bacterial growth, bacterial colonization and biofilm formation, and local and systemic inflammatory responses to devices such as indwelling catheters and tubing used for dialysis or urinary drainage, dental and orthopedic implants, and cardiovascular devices[2].Clinical infections due to bacterial contamination are a significant source of morbidity and mortality; it is estimated that 65–80% of clinical infections are due to biofilm formation is caused by Staphylococcus aureus[3] It is further estimated that S. aureus and S. epidermidis cause about 40%–50% of prosthetic heart valve infections and 50%–70% catheter biofilm infections[4][5]. Collectively, the burden on the healthcare system by S. aureus and S. epidermidis in biofilm is enormous.

3D printing of biocompatible and bioresorbable polymers with tunable properties is a rapidly emerging area of research. Novel biomaterials with tailored surface morphology and properties that can impede bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation are under intense investigation[6]. 3D printing is a significant technology, gaining increased popularity due to the possibility of simultaneous control over surface topology, internal and external architecture, and design complexity[7][8]. It further offers tremendous flexibility and optimization potential through the adjustment of 3D printing parameters along with the application of post-3D printing surface modification, thus, vastly expanding the scope of potential applications[9][10]. It has seen a growing number of novel applications in tissue engineering[11], prosthetics[12][13], and medicine[14][15].

The use of biodegradable polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) has aided in the growth of 3D printed biomedical applications. Though 3D printing material is a technology holding vast potential by itself, a significant hurdle impeding the development of 3D printing lies in the fact that materials used are limited in their bioactivity. 3D printing of artifacts with bioactive properties is a challenge because the majority of bioactive materials are unstable at high temperatures. This issue is further exacerbated by the fact that the majority of mainstream polymers are very stable. Hence, the materials enclosed within the matrix of the 3D printed artifact might remain embedded in the polymer matrix for extended periods until the structure is degraded, and the inherent bioactivity emerges. It is vital to integrate appropriate pre/post printing modification strategies to counter this obstacle[16].

Several post-3D printing modifications procedures have been developed for surface activation of 3D printed constructs including the use of materials to aid in cell attachment such as altering surface properties, and porosity[17], immobilized dopamine on PLA constructs[18], rhBMP2 immobilization[11], integration with chitosan for increased response to macrophages[19], chemical treatment[20], argon, and oxygen treatment for increased cell attachment and proliferation[21].

Chitosan oligosaccharide lactate (COS) is a shorter derivative of chitosan having excellent water solubility, low molecular weight, and shorter chain lengths leading to higher suitability for medical applications; it is biocompatible, biodegradable, non-toxic and suitable for various biomedical applications[22]. Halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) is an aluminosilicate composite that has shown to be a potent drug carrier as its hollow core can be loaded with the material of choice and released in a sustained manner over time[23][24][25]. HNT consists of rolled-up sheets of silica and alumina leading to the opposite charge between the outer surface and inner core, and this chemical duality has enabled functionalization of both surfaces. Several methods have been developed to modify halloysite inner lumen and the outer surface, including acid etching[26], chemical modification[27], use of surface additives[28], and covalent bonding[29]. Chitosan, halloysite and other clay nanoparticle composites have been developed for a variety of antimicrobial and tissue engineering applications[30][31][32]. These studies have shown that composites can be created by blending chitosan with HNTs, montmorillonite or other nanoclays and these are biocompatible and serve well as drug delivery systems[33], addition of thin layer of silver metal to chitosan has shown to lead to antimicrobial effect [34], silver-alginate-chitosan composite [35].

The objective of this study was to functionalize 3D printed PLA constructs with COS-ZnHNTs-Ag having varying concentrations of Ag (5, 10, and 20wt.%, respectively). 3D printed PLA constructs were dipped in 4N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for 10s and dipped in an antimicrobial suspension consisting of chitosan oligosaccharide lactate-zinc halloysite-silver nanoparticles (COS-ZnHNTs-Ag). Functionalized 3D printed PLA constructs were characterized using SEM-EDS, EDS mapping, and FTIR. Antimicrobial effects were studied using the disc diffusion and biofilm assay, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Chitosan oligosaccharide lactate (COS, Mw = 5,000) with a deacetylation degree of 90%, HNTs, sodium hydroxide(NaOH), silver nitrate (AgNO3), zinc sulfate heptahydrate (ZnSO4.7H2O), Mueller-Hinton agar, petri dish were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), 1.75mm PLA filament and MakerBot Replicator Mini 3D printer from MakerBot (Brooklyn, NY).

Experimental

ZnHNTs were prepared using a modified protocol based on an electrolytic method previously described by Mills et al. [36], briefly; an electrolysis setup was assembled consisting of two platinized titanium mesh held parallel at a 2-inch distance and connected to a DC power source (VWR Accupower 500 electrophoresis power supply). Ultrasonicated 100mL aqueous solution of metal salts (2.5mM) and 50mg HNT were dispersed in a glass beaker, and the application of 20V was maintained at 80°C with polarity reversal at every 5min. This step was performed under constant stirring to reduce electrophoretic buildup at the working electrode and thus increase ion density in the solution. Afterward, the supernatant was decanted thrice, and the solution was centrifuged at 5000rpm for 5min with water to separate mHNTs from unabsorbed metal particles and dried at 30°C.

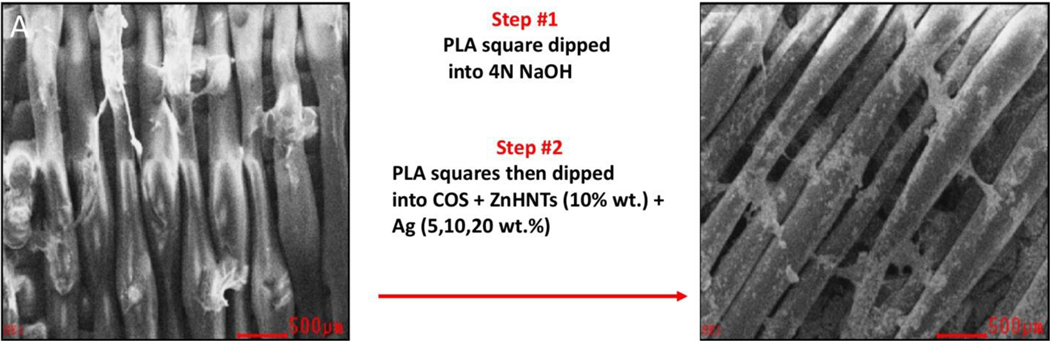

PLA filament (1.75mm in diameter) was used for 3D printing using a MakerBot replicator mini operating at the default print settings (215°C nozzle temperature, 40mm/s printer head speed, 18mm/s filament feed rate). Square constructs, having 20 × 20 × 0.5mm dimensions, were printed. The constructs were dipped in 4N NaOH for 10s for increasing hydrophilicity and subsequently functionalized by dip-coating into aqueous ZnHNTs (10wt.%)-Ag (5, 10, and 20wt./% respectively)-COS suspension (0.1g/20mL) which was previously prepared by overnight magnetic stirring (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for functionalization of 3D printed PLA scaffolds. (A) PLA 3D printed square. (B) A 3D printed square after dipping into COS, ZnHNTs and Ag.

Materials Characterization

Hitachi S-4800 field-emission scanning electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine the surface morphology of the coated HNTs and to visually confirm the presence of the metal coating appearing as clusters on the otherwise smooth outer surface of the HNTs. SEM-EDS were carried out with an EDAX energy dispersive X-ray analyzer linked to the HITACHI S-4800 SEM to evaluate the elemental composition and weight percentage (wt.%) deposition on the AgHNTs. EDS was operated at a working distance of 15mm and an acceleration voltage of 15kV; EDS spectra were analyzed using the EDAX Genesis software. The image resolution was 1024×768, with 0.246×189μm pixel size. The system was configured to collect the backscatter electrons for EDS element mapping. Comparatively, large spot size was used, a dwell time of 256μs was utilized, and total acquisition time was 5min for each sample.

X-ray crystal diffraction analysis was recorded on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, German) with Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). The scan speed and step size used were 2s and 0.02° respectively, the diffraction patterns were recorded on a Philips PW 1710 X-ray powder diffractometer over 2θ within 3° to 85°.

The samples were analyzed using a Thermo/ARLQuant’X energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The X-ray tube was operated at 30 kV for 60 live seconds, using a 0.05 mm (thick) Cu primary beam filter in an air path for silver metal detection. The XRF spectra were studied using Wintrace 7.1™ software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

The Infrared spectrum was recorded at a resolution of 4s−1 with 16 scans using a Thermo Scientific NICOLET™ IR100 FT-IR Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). Thermo Scientific OMNIC™ software was used to study the transmittance of the chemical bonds.

Microplate absorbances were analyzed using Biotek 800TS microplate reader (Winooski, VT) set at 630nm absorbance.

Antibacterial activity

S. aureus was used in this study; it was maintained in tryptic soy agar. For testing, the bacterial strain was cultured in nutrient broth and plated on Muller-Hinton agar plates at 37°C overnight after which a single colony was picked up using a sterile toothpick and suspended in saline solution and diluted to 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml), 20μL of which was spread over Muller-Hinton agar plates on which the test materials were placed and incubated for 12–18hr at 37°C and the obtained zones of inhibition were analyzed using ImageJ software.

The antibacterial potential was also evaluated against S. aureus using a microdilution broth assay. Samples were cut and immersed in 24 well plates containing 1–3mL/well Muller Hinton broth (depending on the sample dimension) inoculated with 20μL of 0.5 McFarland standard S. aureus, the plates were put on a shaker, after 4hr the samples were removed, and the absorbance of 100μL solution was recorded after 12hr.

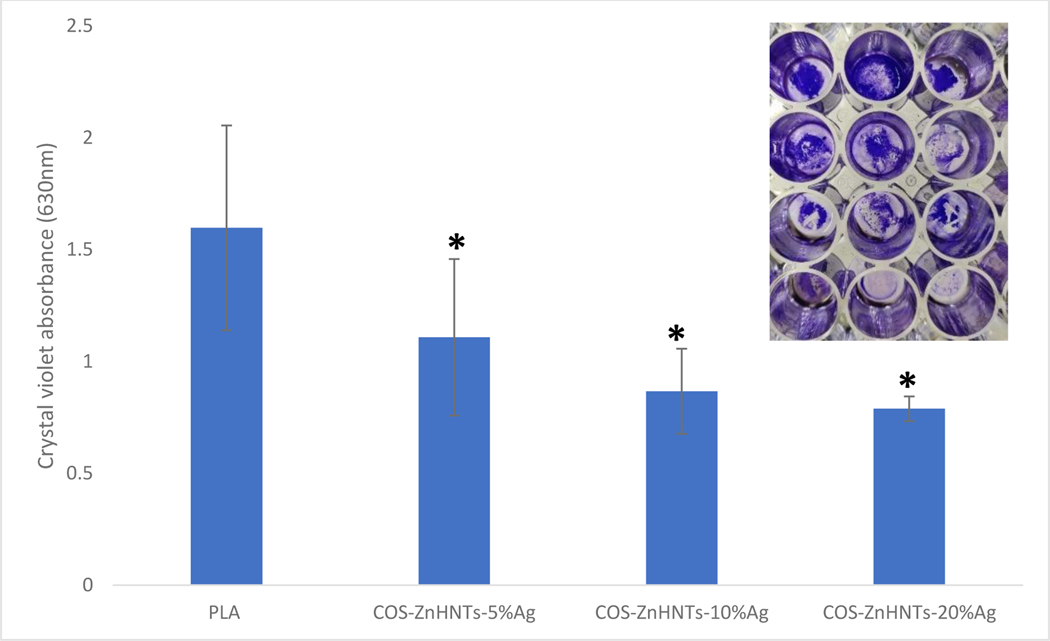

Biofilm assay was performed using the crystal violet assay, briefly, samples were incubated in 2mL nutrient broth in 48 well plates inoculated with 1OD S. aureus for 2 days at 37°C, at the end of which the plate was emptied by inverting and gently tapping in order to remove lightly attached planktonic bacteria. The remaining bacterial films were stained with aqueous crystal violet (0.1%w/v) for 10min, which was similarly removed by inversion and tapping to ensure optimal removal of unattached bacteria, acetic acid (30%) was added to each well to solubilize the stain and absorbance at 630nm was recorded[37].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel Analysis ToolPak plugin and Origin 9.6. Linear regression was used to construct and correlate standard curves. All experiments were done in triplicate, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with p < 0.05 as the significance level was utilized for statistical analysis, and further analysis was performed using a 2 tailed Student’s t-test. Statistically significant data was reported (p < 0.05), and all the results were reported as mean ± standard deviation (p < 0.05, n=3).

Results and Discussion

Functionalization of PLA constructs

ZnHNTs and Ag+ ions adsorb to COS, which helps in stabilizing the suspension, which was magnetically stirred in order to prevent settling down of the suspension. Unmodified PLA constructs were unreactive, and no attached suspensions were observed, and this was probably due to a lack of surface charges. With surface activation, hydrophilicity was enhanced by chemical treatment; it led to the cleavage of the ester bond of PLA and resulted in the formation of carboxyl and hydroxyl end groups, respectively (Figure 2), which can then bind dispersed COS with Ag and ZnHNTs.

Figure 2.

Hydrolysis of the ester bond in the PLA backbone results in carboxyl and hydroxyl end groups[20].

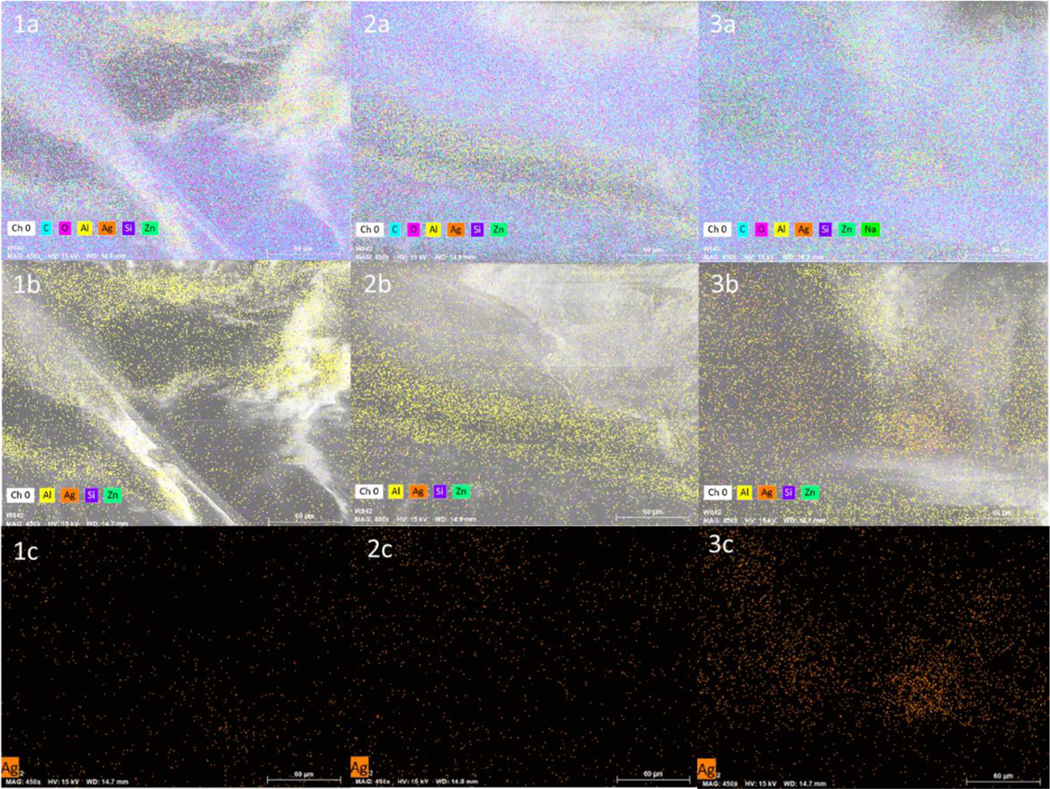

Microstructure and chemical composition of the composite coatings

Figure 3 shows the functionalized 3D printed constructs, increasing silver concentration in the constructs led to darker morphology. The morphology of the coatings was characterized using SEM-EDS. A representative SEM-EDS micrograph is shown in Figure 4. A uniform layer of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag is observed for all the samples and increasing the amount of silver content in the suspension led to an increased Ag accumulation (wt.%). Further, a uniform distribution of the HNTs throughout the chitosan matrix, hence, verifies a more systematic mixing of the HNTs throughout the material.

Figure 3.

3D printed PLA and functionalized PLA. (A) unmodified; functionalized with COS-ZnHNTs-5%Ag (B), COS-ZnHNTs-10%Ag (C), and COS-ZnHNTs-20%Ag (D).

Figure 4.

SEM-EDS map of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag in PLA at 5 (1a, 1b, 1c), 10 (2a, 2b, 2c), 20 (3a, 3b, 3c) wt.% respectively.

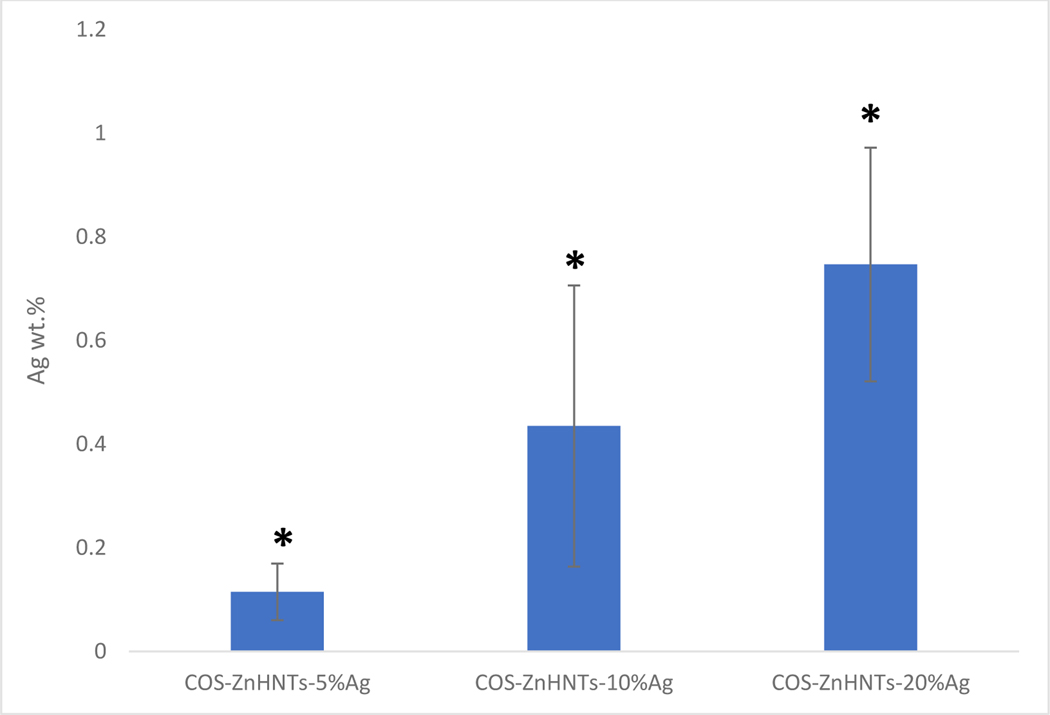

EDS analysis of the functionalized 3D printed PLA constructs showed that an increase in the Ag concentration in the COS-ZnHNTs-Ag suspensions led to higher Ag deposits during the functionalization process (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

EDS analysis of Ag content in the coatings, increasing Ag wt.% in functionalized PLA was observed with a corresponding increase in Ag content in the COS-ZnHNTs-Ag suspension, (p < 0.05, n=3).

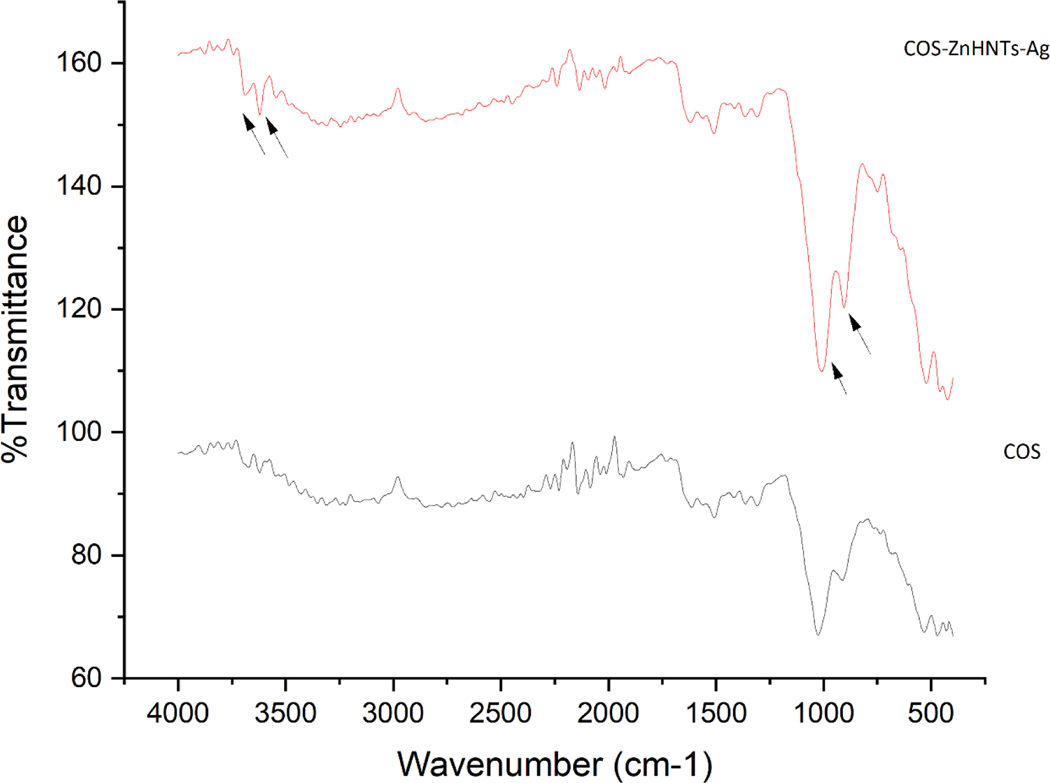

FTIR was used for chemical analysis and characteristic bands for COS at 3307 for O-H and 2840cm−1 for C-H stretch respectively, peaks for the secondary amide group bending were also observed at 1508 and 1027cm−1 respectively. On addition of ZnHNTs more pronounced peaks were observed at 1009 and 913cm−1 respectively corresponding to in-plane Si-O stretching, and O-H deformation of the inner surface hydroxyl groups (Figure 6), further the band at 1025.9 cm−1 corresponding to C-O stretching displayed a prominent shift at lower frequency 1008cm−1 indicating the formation of hydrogen bonds with ZnHNTs.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of COS and COS-ZnHNTs-Ag.

Antimicrobial studies

Biofouling of medical devices is a constant threat and the leading cause of infections. The present study was aimed at developing an antimicrobial coating possessing an antimicrobial capability that can be used for functionalizing 3D printed constructs. Antibacterial potential of the samples was evaluated against gram-positive S. aureus bacteria, which is the most common bacteria in clinical biofouling using agar diffusion method, and the coatings exhibited substantial inhibition zones, which can be attributed to release of silver and zinc nanoparticles.

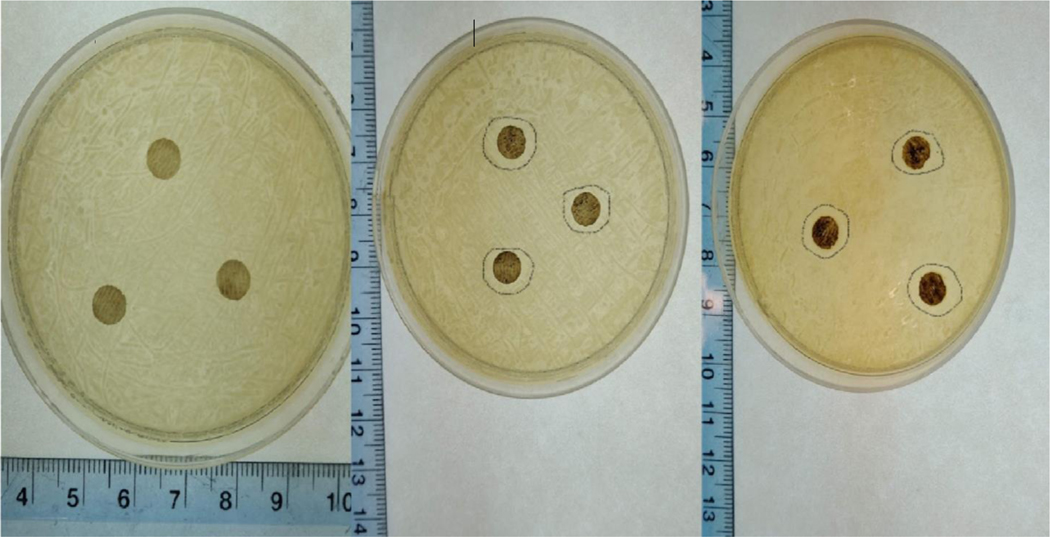

Figure 7 shows the average inhibition zone diameter, and the antimicrobial activity was found proportional to the Ag content in the constructs, at low concentration (5% Ag) no antimicrobial effect was observed. Similar results have been reported previously, where increasing concentrations of AgNPs led to increased antimicrobial activity [38].

Figure 7.

Average inhibition diameter against S. aureus, a. COS-ZnHNTs-5%Ag (none), b. COS-ZnHNTs-10%Ag (0.76mm±.004), and c. COS-ZnHNTs-20%Ag (0.80mm±0.01), (p < 0.05, n=3).

In a similar study, 3D printed polyetheretherketones functionalized with dopamine showed antimicrobial effects only when Ag was deposited18. The observed antimicrobial effect can be attributed to the presence of AgNPs, ZnHNTs, and chitosan, as previously reported in the literature. The antimicrobial effect can be explained due to the destruction of the bacterial cell wall and denaturing of the cell enzymes by reactive oxygen species generated by silver nanoparticles.

Figure 8 shows the crystal violet biofilm assay for the functionalized constructs, increasing silver content had an inhibitory effect on the biofilm formation, silver is a well-known antimicrobial agent that has significant anti-biofilm properties well documented in numerous studies[39,40].

Figure 8.

Crystal violet biofilm assay, increasing Ag content in the coatings had an inhibitory effect on the S. aureus biofilm formation. Inset – a. control (b, c, d) COS-ZnHNTs- 5, 10, and 20% Ag respectively, (p < 0.05, n=3).

The data shows that COS-ZnHNTs-Ag functionalized coatings possessed anti-biofouling activity that can be attributed mainly to Ag and Zn ion release; furthermore, the positively charged COS surface interacts strongly with the bacterial membrane thus, supplementing the anti-biofouling effect.

Conclusion

3D printed PLA squares were printed, and their surfaces were then chemically altered to increase hydrophilicity, and suspensions of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag were adsorbed on the construct surface. Morphological surface characterization using SEM-EDS confirmed the presence of the suspension coatings on the constructs, FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of COS-ZnHNTs-Ag in the coatings. Antibacterial evaluation using the agar diffusion method confirmed the anti-biofouling potential of the PLA constructs (which was a function of the Ag content in the material). Thus, we demonstrate successful development and evaluation of a functionalization coating having antimicrobial activity for 3D printed constructs.

Acknowledgments:

A.H. and Y.L. thank D.K.M. (PI) for advice and guidance. Mr. Davis Bailey and Dr. Sven Eklund for equipment training.

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding assistance provided by the Center for Dental, Oral & Craniofacial Tissue & Organ Regeneration (C-DOCTOR) with the support of NIH NIDCR (U24DE026914) and support provided by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20 GM103424-17 DOD 301-662-5127.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wolcott RD; Ehrlich GD Biofilms and chronic infections. Jama 2008, 299, 2682–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darouiche RO Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N. Engl. J. Med 2004, 350, 1422–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris LG; Richards RG Staphylococci and implant surfaces: a review. Injury 2006, 37, S3–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M; Yu Q; Sun H. Novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of biofilm related infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2013, 14, 18488–18501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khatoon Z; McTiernan CD; Suuronen EJ; Mah T-F; Alarcon EI Bacterial biofilm formation on implantable devices and approaches to its treatment and prevention. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard DH; Tappa K; Boyer CJ; Jammalamadaka U; Hemmanur K; Weisman JA; Alexander JS; Mills DK; Woodard PK Antibiotics in 3D-printed implants, instruments and materials: benefits, challenges and future directions. J. 3D Print. Med 2019, 3, 83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisman JA; Nicholson JC; Tappa K; Jammalamadaka U; Wilson CG; Mills DK Antibiotic and chemotherapeutic enhanced three-dimensional printer filaments and constructs for biomedical applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stansbury JW; Idacavage MJ 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent. Mater 2016, 32, 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaezi M; Seitz H; Yang S. A review on 3D micro-additive manufacturing technologies. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol 2013, 67, 1721–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhushan B; Caspers M. An overview of additive manufacturing (3D printing) for microfabrication. Microsyst. Technol 2017, 23, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SJ; Lee D; Yoon TR; Kim HK; Jo HH; Park JS; Lee JH; Kim WD; Kwon IK; Park SA Surface modification of 3D-printed porous scaffolds via mussel-inspired polydopamine and effective immobilization of rhBMP-2 to promote osteogenic differentiation for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2016, 40, 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh C-H; Chen Y-W; Shie M-Y; Fang H-Y Poly (dopamine)-assisted immobilization of Xu Duan on 3D printed poly (lactic acid) scaffolds to up-regulate osteogenic and angiogenic markers of bone marrow stem cells. Materials (Basel). 2015, 8, 4299–4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gretsch KF; Lather HD; Peddada K. V; Deeken, C.R.; Wall, L.B.; Goldfarb, C.A. Development of novel 3D-printed robotic prosthetic for transradial amputees. Prosthet. Orthot. Int 2016, 40, 400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuniga J; Katsavelis D; Peck J; Stollberg J; Petrykowski M; Carson A; Fernandez C. Cyborg beast: a low-cost 3d-printed prosthetic hand for children with upper-limb differences. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisman JA; Ballard DH; Jammalamadaka U; Tappa K; Sumerel J; D’Agostino HB; Mills DK; Woodard PK 3D printed antibiotic and chemotherapeutic eluting catheters for potential use in interventional radiology: in vitro proof of concept study. Acad. Radiol 2019, 26, 270–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domínguez-Robles J; Mancinelli C; Mancuso E; García-Romero I; Gilmore BF; Casettari L; Larrañeta E; Lamprou DA 3D Printing of Drug-Loaded Thermoplastic Polyurethane Meshes: A Potential Material for Soft Tissue Reinforcement in Vaginal Surgery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tappa K; Jammalamadaka U; Ballard DH; Bruno T; Israel MR; Vemula H; Meacham JM; Mills DK; Woodard PK; Weisman JA Medication eluting devices for the field of OBGYN (MEDOBGYN): 3D printed biodegradable hormone eluting constructs, a proof of concept study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao C-T; Lin C-C; Chen Y-W; Yeh C-H; Fang H-Y; Shie M-Y Poly (dopamine) coating of 3D printed poly (lactic acid) scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 56, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almeida CR; Serra T; Oliveira MI; Planell JA; Barbosa MA; Navarro M. Impact of 3-D printed PLA-and chitosan-based scaffolds on human monocyte/macrophage responses: unraveling the effect of 3-D structures on inflammation. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tham CY; Hamid ZAA; Ahmad ZA; Ismail H. Surface engineered poly (lactic acid)(PLA) microspheres by chemical treatment for drug delivery system; Trans Tech Publ, 2014; Vol. 594; ISBN 3037859377. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canullo L; Genova T; Wang H-L; Carossa S; Mussano F. Plasma of Argon Increases Cell Attachment and Bacterial Decontamination on Different Implant Surfaces. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mourya VK; Inamdar NN; Choudhari YM Chitooligosaccharides: Synthesis, characterization and applications. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2011, 53, 583–612. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordeepong S; Bhongsuwan D; Pungrassami T; Bhongsuwan T. Characterization of halloysite from Thung Yai District, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, in Southern Thailand. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol 2011, 33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lvov Y; Wang W; Zhang L; Fakhrullin R. Halloysite clay nanotubes for loading and sustained release of functional compounds. Adv. Mater 2016, 28, 1227–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan P; Tan D; Annabi-Bergaya F. Properties and applications of halloysite nanotubes: recent research advances and future prospects. Appl. Clay Sci 2015, 112, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yah WO; Takahara A; Lvov YM Selective modification of halloysite lumen with octadecylphosphonic acid: new inorganic tubular micelle. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 1853–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taroni T; Meroni D; Fidecka K; Maggioni D; Longhi M; Ardizzone S. Halloysite nanotubes functionalization with phosphonic acids: Role of surface charge on molecule localization and reversibility. Appl. Surf. Sci 2019, 486, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan D; Yuan P; Liu D; Du P. Surface modifications of halloysite. In Developments in Clay Science; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 7, pp. 167–201 ISBN 1572–4352. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massaro M; Lazzara G; Milioto S; Noto R; Riela S. Covalently modified halloysite clay nanotubes: synthesis, properties, biological and medical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 2867–2882, doi: 10.1039/C7TB00316A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong SI; Lee JH; Bae HJ; Koo SY; Lee HS; Choi JH; Kim DH; Park S; Park HJ Effect of shear rate on structural, mechanical, and barrier properties of chitosan/montmorillonite nanocomposite film. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2011, 119, 2742–2749. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu M; Zhang Y; Wu C; Xiong S; Zhou C. Chitosan/halloysite nanotubes bionanocomposites: structure, mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2012, 51, 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J; Wu Y; Shen Y; Zhou C; Li Y-F; He R-R; Liu M. Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin for breast cancer using chitosan oligosaccharide-modified halloysite nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 26578–26590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mousavi SM; Hashemi SA; Salahi S; Hosseini M; Amani AM; Babapoor A. Development of Clay Nanoparticles Toward Bio and Medical Applications. Curr. Top. Util. Clay Ind. Med. Appl 2018, 9, 167. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pišlová M; Šubrt M; Polívková M; Kolářová K; Švorčík V. Deposition of thin metal layers on chitosan films. Mater. Technol 2018, 33, 845–853. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bousalem N; Benmansour K; Ziani Cherif H. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial silver-alginate-chitosan bionanocomposite films using UV irradiation method. Mater. Technol 2017, 32, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mills D; Boyer C. Method for metalizing nanotubes through electrolysis 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Toole GA Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. JoVE (Journal Vis. Exp 2011, e2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sondi I; Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci 2004, 275, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Gutierrez F; Boegli L; Agostinho A; Sánchez EM; Bach H; Ruiz F; James G. Anti-biofilm activity of silver nanoparticles against different microorganisms. Biofouling 2013, 29, 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palanisamy NK; Ferina N; Amirulhusni AN; Mohd-Zain Z; Hussaini J; Ping LJ; Durairaj R. Antibiofilm properties of chemically synthesized silver nanoparticles found against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Nanobiotechnology 2014, 12, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]