Abstract

There are known disparities in the burden of illness and access/quality of care for African, Latino/a, Asian, and Native American (ALANA) patients diagnosed with depressive disorders, which may occur because of health inequities. Racial stress and trauma (RST), or the significant fear and distress that can be imparted from exposure to racism, is one such inequity linked to the development of depression. The current review summarizes past research examining the association between racism, RST, and depression, as well as avenues in which RST becomes biologically embedded in ALANA individuals. We describe multimodal research that supports vigilance as a potential mediator of the association between RST and depression and consider the nuanced role that vigilance plays during experiences with racism. Finally, we describe methodological advances in the assessment of vigilance evoked by RST and the clinical implications that may be generated by future improvements. In each of these areas, we present examples of how ongoing and future research can be leveraged to provide support for psychosocial programs that facilitate autonomous community healing and resilience, increase calls for public policy changes, and support clinical interventions that lessen the burden of racism on ALANA communities.

Keywords: racism, racial stress and trauma, adolescent depression, vigilance, adolescence

Childhood adversity accounts for over 50% of risk for the development of affective problems such as depression. 1 To probe the link between adversity and mental health outcomes, traditional assessments of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have queried experiences such as parental loss, bullying, and childhood sexual, emotional, or physical abuse. 2 Yet, racism has historically been neglected in these assessments despite being a ubiquitous form of childhood adversity affecting African, Latino/a, Asian, and Native American [ALANA 3 ] youth 4 and a primary driver of health inequities in the United States. 5 This is a critical gap in etiological models of depression in part because encounters with racism can lead to racial stress and trauma (RST), which is a known risk factor for the development of depression.6–8 Further, this initial increase in depression may serve as a harbinger of enduring distress and impairment. ALANA individuals suffer from more chronic, severe, and debilitating episodes of clinical depression 9 and report disparities in access, uptake, and retention in evidence-based treatments, compared to their White counterparts.10,11 There is a pressing need to examine mechanistic pathways linking RST to future depression in ALANA youth to advise public policy and early intervention efforts that address the health inequities imparted by racism. To this aim, the current review seeks to 1) summarize prior research assessing links between racism, RST, and depression (across multiple levels of analysis and development) and 2) consider vigilance for racism-related harm as a potential mechanism underlying the link between RST and the development of depression.

Racism and Mental Health

The National Institutes of Health recently defined racism as “a socially structured action that is unfair or unjustified” and that is based on race or ethnicity, which are regarded as social (not biological) constructs, 12 though the effects of racism are often biological in nature. 13 Racism, inclusive of unequal actions, beliefs, and behaviors towards ALANA individuals, permeates most aspects of their daily living, including employment, academic, and retail sectors, as well as during police encounters. 14 Often research examining racism as a source of adversity centers on its behavioral expression, racial discrimination. 15 Yet, the adverse influence of racism is also generated by macrosystems.16,17 For example, the effects of systemic racism on households (eg, disparate distribution of wealth and resources; inequities in access to education and healthcare; overrepresentation in the criminal justice system) also increase risk for other types of ACEs across ALANA youth, particularly among youth who identify as Black or Latino/a. 18 Greater exposure to racism, from micro- to macrosystems, increases risk for negative mental health outcomes among ALANA youth, including risk for depression and other internalizing symptoms such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms.5–7,19,20

Stress and trauma following racist encounters is a putative link between exposure to racism and the development of depression. Racism-based traumatic stress theory illustrates that racism causes emotional injury (ie, RST) and thus should be considered by mental health providers as a specific trauma type to center racism as an external and/or situational factor that is outside of an individual’s control and caused by injustice and oppression. 14 RST can follow both direct (first-hand) and indirect (second-hand) encounters with racism and may include feelings of distress, anxiety, avoidance, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, dissociation, anger, and reduced self-esteem. 21 A recent meta-analysis demonstrated moderate to strong associations between racial discrimination and reported trauma symptoms among adults in the United States, 22 providing additional support for racism as a mechanism of stress and trauma among ALANA communities. Although there is considerable overlap between symptoms of RST and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and there is the potential for RST to lead to a diagnosis of PTSD and/or exacerbate existing PTSD symptoms, 23 it is important to note that these two clinical phenomena remain distinct, and may necessitate distinct intervention approaches, in part because RST results from a lifelong and unavoidable exposure to racism that repeatedly unfolds across generations, communities, and history.

Racial Stress and Trauma and the Development of Depression

There is a robust association between experiences with racism and youth depression [for reviews, see8,24] and evidence that the development of RST precedes and increases risk for depressive symptoms among ALANA youth.25–28 When examining the temporal links between RST and depression, adolescence may be a critical developmental window to consider as 1) rates of clinical depression skyrocket during this period, particularly for girls across races 29 and 2) there is a graded association between cumulative ACE exposure and later depression and other internalizing problems during adolescence.30,31 Although most of the past research examining RST has focused on adults, there are several developmental models that consider the ecological contexts in which youth encounter and respond to racism across distinct developmental periods.32–34 For example, Saleem and colleagues’ developmental and ecological model of youth racial trauma [DEMYth-RT 34 ] describes critical ecological and developmental changes from late childhood to adolescence that may support a link between RST and the development of depression during this period. During elementary school (6-11 years), children learn that the color of their skin can impact how they are treated by others and can influence their safety and security. 34 By middle school (12-14 years), there is an increasing relation of the self to sociocultural identities, including ethnicity and race, 35 and a heightened sensitivity to both positive and negative evaluation from peers. 36 During high school (15-18 years), ALANA youth experience increasing exposure to racism given their greater autonomy from proximal adults and, as a result of increased cognitive processing, develop a more advanced understanding of the systems and institutions that maintain and perpetuate racism. 37 Together, these developmental and ecological changes set the stage for an increasing impact of racism on mental health as ALANA youth learn to navigate various sectors of their lives. 34 For example, as it relates to the child’s development as an individual, exposure to racism, particularly from peers, may be especially damaging to self-esteem during this sensitive window for identity development. 38 At an interpersonal level, adolescents’ increasingly comprehensive understanding of the impact of racism may lead to increased worry about the safety and well-being of one’s self and loved ones. 39 Of note, symptoms of RST during adolescence may resemble the symptoms commonly seen in adults but may also include anxiety and difficulty maintaining attention and concentration in school 40 and an increase in substance use, risk-taking, and social withdrawal.27,41,42

Although RST increases risk for many forms of psychopathology,43–45 adaptations of general strain theory 46 suggest that RST may specifically heighten risk (or strain) for depression by increasing negative emotionality and lowering self-esteem and self-worth. 47 This theory is supported in part by the large number of studies demonstrating that higher levels of racial discrimination during childhood increases risk for the development of depression during adolescence and young adulthood among ALANA youth7,8,24–28 and that self-esteem may mediate the link between racism and depression.48–51 Similarly, Brondolo and colleagues updated longstanding cognitive models of depression to reflect how racism may specifically impact vulnerability for depression. This social-cognitive model describes how racism can affect depression-relevant cognitive schemas about the self (eg, self-esteem, locus of control), others (eg, stereotype threat), and the world (eg, public regard, unjust world beliefs). 6 In addition to the effects on self-esteem described above, racism can lead to reduced perceptions of personal control (ie, an ability to get ahead in life and/or maintain safety)52,53 and increased beliefs about a hostile world, 51 both of which have been shown to mediate the link between exposure to racism and depression. 6 At a more granular level, a recent daily diary study demonstrated that when Black youth experienced increases in low public regard (ie, an individual’s belief about the extent to which society views their racial group negatively), experiences with racial discrimination became more likely to predict increases in depressive symptoms the following day. 54

Exposure to racism can also dampen cognitive flexibility, which increases risk for depression. 6 Following an incident of racial discrimination, the targeted individual will likely exert considerable cognitive resources to appraise if the act was intentional or not and decide how to respond and cope, all of which comes at a cost to other competing cognitive demands.55,56 This hypothesis is supported in part by research showing that while cognitive performance in Black adults is impacted by displays of blatant racial discrimination, 57 performance suffers more following subtle incidents of racism. 58 Critically, this reduction in cognitive flexibility is thought to limit an individual’s ability to shift thoughts and attention away from past or ongoing events that evoke feelings of low self-esteem or personal control, which maintains and increases symptoms of depression; indeed, such hypotheses have been supported by research showing that rumination is a mediator of the link between exposure to racism and later depression in ALANA young adults59–61 and adolescents. 62

Finally, chronic stress derived from racism may also be a pathway to depression. Racism is one of the largest sources of chronic stress for ALANA individuals, and research shows that racism-related stressors are often more deleterious to health and well-being than other stressors.6,63 In response to racism-related chronic stress, Wilson and Gentzler (2021) describe an “adaptive culture to cope”, which includes high levels of emotional self-control and limited self-disclosure of negative emotion. Although this coping style offers adaptive strategies to mitigate racism-related barriers in various interpersonal settings, it also requires high levels of effort to sustain, which taxes mental resources and increases wear and tear on biological systems. 64 Likewise, avoidant coping strategies in response to racial discrimination, such as expressive suppression of negative emotion or acceptance and resignation, are associated with increased avoidance symptoms of trauma (dissociation, emotional numbing) following racial discrimination.65,66 Although additional research is needed in youth, avoidant coping in response to chronic racism-related stress has been shown to increase risk for depression among Latina and Black adults,67,68 which is consistent with developmental models that show that expressive suppression 69 and blunted emotional responding 70 are strong predictors of youth depression.

The Impact of Microaggressions and Indirect Racism on Mood and Depression

In addition to the well-described effects of direct and overt exposure to racial discrimination, depression risk can also be increased by exposure to 1) ambiguous or subtle racial discrimination, including microaggressions, and 2) indirect racial discrimination, including anticipated discrimination and vicarious discrimination.47,71 Microaggressions are defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults to the target person or group”, 72 and they have been shown to evoke similar levels of anxiety, anger, and stress when compared to experiences with overt discrimination. 73 For example, given their pervasive nature in daily life, microaggressions can result in ALANA youth feeling isolated from peers, out of place in academic settings, and/or unwelcomed during business transactions. Critically, many studies have shown a robust link between microaggressions and depression in ALANA adults and adolescents,73–75 with evidence that RST mediates the link between frequency of microaggressions and depressive symptoms.76,77

Similarly, studies have shown that indirect discrimination, including anticipated (ie, high expectations that discrimination will occur in the future or that ongoing discrimination will endure) and vicarious discrimination (ie, the discovery of and identification with the harm inflicted upon others), are significantly associated with depressive symptoms and disorders among ALANA adolescents47,78 and adults. 79 With adolescents increasingly experiencing life through mobile screens, an expanded focus on understanding how indirect discrimination experiences unfold both on and offline is imperative. For example, a recent study found that Black adolescents face, on average, five racial discrimination encounters per day, with the majority of these experiences occurring online. 80 Online experiences may be especially relevant for the development of depression because when indirect discrimination is widely disseminated via viral media, targeted individuals become more likely to 1) internalize observed negative evaluations about ALANA individuals and communities and 2) perceive less personal control, both of which increase the risk for depression. 6 A recent qualitative analysis conducted by Heard-Garris and colleagues (2021) revealed that adolescents describe a near constant stream of information reaching them through mobile devices, particularly through social media applications such as YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and Snapchat, and many adolescents report encountering daily instances of racism in the news. During and after these indirect encounters with racism, respondents reported feeling helpless, desensitized, and stressed, which often led them to seek out support from peers, family, and community mentors and/or to engage in soothing activities, such as writing, music, or games. 81 Similarly, among ALANA adults, respondents reported that the Internet has led to 1) greater exposure to racism and 2) elevation and amplification of racist voices. 82 Further, adults deemed exposure to racist jokes/humor, racist propaganda, vicarious observation of direct racism toward others, negative racial stereotyping, and racism in online media as the most damaging to their health. 82

As expected, these qualitative findings parallel results from quantitative, correlational designs examining the impact of indirect discrimination experiences on mental health. For example, Bor and colleagues (2018) quantified the number of days adult respondents were exposed to media coverage of one or more police killings of unarmed Black Americans in their state of residence. For Black respondents, coverage of every additional police killing of an unarmed Black person was associated with an increase in poor mental health days (ie, mental health rated as “not good”), whereas exposure to police killings of either Black or White people had no impact on mental health among White respondents. 83 Among studies specifically examining depressive symptoms, greater online exposure to viral videos and images of racial discrimination and violence perpetuated against ALANA individuals (eg, undocumented immigrants detained in cages; unarmed Black people killed by police or civilians) was related to higher depressive symptoms among ALANA adolescents84,85 and adults.79,86 Together, these qualitative and quantitative studies provide striking evidence that ALANA adolescents and adults are inundated by chronic indirect exposure to racism via mobile devices and news media and suggest that these experiences may increase risk for depression via RST, particularly for Black and Latino/a adolescents who may face the highest levels of exposure and distress. 84

Biological Embedding of Racial Stress and Trauma

Occurring in parallel and in interaction with the psychological impact propagated by systems that support racism (both online and off), there is also a biological embedding of RST among ALANA individuals. 13 Specifically, Carter and colleagues propose that dimensions of threat processing [eg, responses to acute, sustained, and potential threat, as described in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) ‘Research Domain Criteria’ (RDoC) framework] are a critical mechanism of neurobiological embedding. Relevant to the construct of sustained threat, Clark and colleagues (1999) biopsychosocial model illustrates that chronic stress from racial discrimination and threat over time contributes to heightened allostatic load (ie, the accumulation of wear and tear on the body and brain via chronic stress processes).63,87 Research supporting the biopsychosocial model is overwhelming; 88 cumulative levels of exposure to racial discrimination and systemic racism are linked to elevated inflammatory markers,44,89–91 accelerated biological aging and allostatic load,92,93 reduced total brain matter volume, 94 decrements in white matter microarchitecture, 95 and heightened amygdala reactivity and functional connectivity. 96 Notably, each of these indices predicts premature morbidity and mortality91,97,98 and mirrors putative biomarkers of depression.94,99–101

Another form of biological embedding from RST can be captured in the moments when an individual is faced with acute threat. Although no studies of which we are yet aware have probed neurobiological responses to overt cues of racism-related threat, one study showed that among a sample of predominantly Black adults, a psychophysiological “over-expression of fear” was linked to greater intrusive thoughts in response to a reminder of a past trauma. 102 Similarly, Fani and colleagues (2021) showed that trauma-exposed Black women with higher levels of exposure to racial discrimination exhibited greater activation in brain regions related to cognitive-affective and attentional functions [ie, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (PFC) and middle occipital cortex] when viewing trauma-related threat stimuli during an affective Stroop task. Critically, these findings were maintained after accounting for PTSD symptoms and other trauma exposures, 103 suggesting that these neurobiological disruptions in attention to and regulation of threat processing were specific to biological embedding of RST. In contrast, there is also evidence suggesting that exposure to racism can be associated with blunted responses during fear conditioning, as research has shown that Black adults, compared to White peers, exhibit lower skin conductance104,105 and reduced activation of fear circuitry during fear conditioning. 105 Notably, a recent study by Harnett and colleagues (2019) found that racial differences in neurobiological fear conditioning responses were mitigated when considering lifetime levels of violence exposure, family income, and neighborhood disadvantage, 105 which highlights the critical role played by the correlates of structural racism (ie, increased life stress and disadvantage) in health equity and biological embedding of trauma [see also 106 ].

Responses to potential racism-related threat are also likely to be biologically embedded. Although very little research has examined how the embodiment of RST may unfold across development, the current generation of adolescents and young adults are among the first to grow up with almost daily exposure to viral media depicting racialized violence, 81 which will likely have long lasting effects on how the brain and related neurobiological systems process potential threat. 13 Such patterns of threat processing will develop in conjunction with cognitive schemas that are shaped by racism, which can facilitate increased perceptions of potential threat even in times of safety.6,107 For example, a recent observational study of Black adolescents found that as personal experiences of racism increased across individual, institutional, and cultural levels, so did anticipatory racism-related stress responses across both cognitive-affective and physiological domains. 108 Similarly, experimental studies have shown that adolescents and adults who identify as Black or Latino/a, compared to White, experience increased sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and reduced parasympathetic nervous system activity when observing or speaking about incidents of racism perpetuated against other people or when anticipating that the incident might happen to them.73,109–114 Taken together, these findings suggest that ALANA youth are likely to express heightened vigilance for racism-related threats across multiple units of analysis, which may put them at elevated risk for RST and later depressive symptoms. 90

Vigilance for Racism-Related Threats

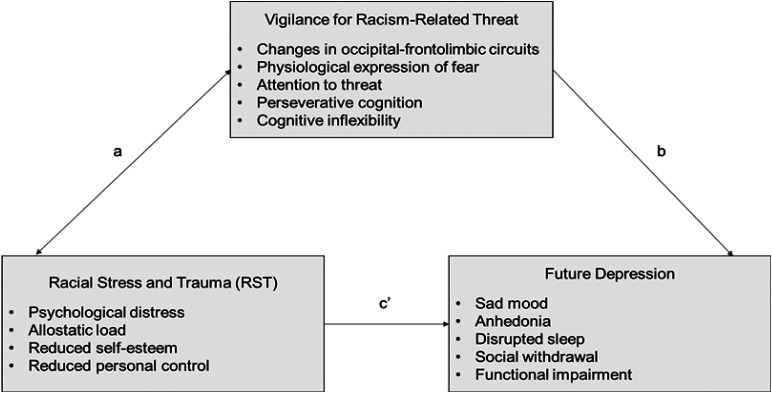

Consistent with RST models describing biological embedding 13 and relevant developmental and ecological contexts, 34 generalized developmental models of adversity maintain that trauma exposures specifically involving threat of harm can lead to biopsychosocial changes in youth that influence how they process and attend to threat-relevant information in the external environment. 115 The terms ‘vigilance’ or ‘hypervigilance’ to threat are commonly used in the psychological literatures on anxiety, depression, and trauma to describe a pattern of both voluntary and involuntary (automatic) selective processing of threat-relevant cues within the environment, relative to cues that are positive or neutral. Together, these models suggest that vigilance for potential racism-related threats are likely to 1) interfere with goal-directed behavior required for adaptive functioning, 2) maintain a reciprocal relation with fear and distress, such that more vigilance increases symptoms of RST and vice versa, and 3) predispose ALANA youth to future affective problems such as depression.13,34,115 Thus, vigilance for racism-related threats may be a critical mechanism predisposing ALANA youth, and particularly Black and Latino/a adolescents, to future depression, likely by mediating the link between RST and depression (Figure 1). This hypothesis is also supported by research showing that self-reported levels of vigilance increase risk for depression among ALANA adults.79,116,117

Figure 1.

Vigilance for racism-related threats as a mechanism predisposing ALANA youth to future depression.

Vigilance: Adaptation, Resilience, and Oppression

It is critical to note here that although vigilance and its neurobiological concomitants have been conceptualized as vulnerabilities in traditional developmental models of affective disorders, 118 vigilance may simultaneously provide distinct advantages to ALANA youth when navigating a world where racism is ubiquitous; thus it may be considered adaptive, particularly in the short-term. For example, vigilance may 1) help individuals foresee and circumvent racism-related threats and 2) buffer self-esteem and mood by helping attribute racist denigrations and exclusions to external rather than internal causes,90,108 while concurrently reducing activation of brain regions responsible for social pain. 119 Yet, despite their resilience, it cannot be overlooked that this need for vigilance places an oppressive burden on ALANA youth that is inconsistent with the ideals and actions of a just society. To maintain heightened vigilance throughout the day, selective attention is manifested across multiple domains (physical, behavioral, cognitive-affective, and neural),90,117 which is taxing for myriad reasons. First, vigilance is typically accompanied by feelings of worry or tension that, in turn, motivate the persistent monitoring and avoidance behaviors required to maintain perceptions of safety. 120 The perseverative cognition and emotions that likely accompany a perpetual state of vigilance for racism-related threats can quickly deplete coping resources, leading to increased negative mood such as depression. 116 Second, attending, interpreting, and responding to ambiguous threat cues interferes with other attentional and cognitive demands that are integral to daily living and to the capacity to engage fully in preferred activities.56,121 Indeed, vigilance taxes youth across most domains of adaptive functioning, 63 leading to worse performance in school and at work, 122 difficulties sleeping, 123 chronic stress, 124 and increased social withdrawal. 125

Finally, vigilance for threat of racism-related threats is likely to both tax and shape the neural architecture required to support threat processing and emotion regulatory systems across development. Although there is a dearth of studies examining the influence of racism on neuroanatomy and functional integration during childhood and adolescence, research on child maltreatment may begin to illuminate how the developing brain is impacted. Many of the most devastating effects of racism on ALANA youth overlap with components of childhood maltreatment 4 (eg, disparagement or destruction of things a child values; elicitation of guilt, shame, or fear; observations of violence perpetuated against people a child identifies with or cares for; unwarranted expectations that a child should cope with situations that exceed their developmental abilities). There is growing consensus that distinct forms of maltreatment cause experience-dependent alterations in the brain and its circuits that serve to facilitate the individual’s adaptation to and survival in a threatening world, which may lead to alternative etiological pathways to psychiatric disease compared to non-maltreated individuals. 126 For example, compared to adults with no such exposure, adults who visually witnessed domestic violence repeatedly during childhood exhibited reduced grey-matter density in the right lingual gyrus and portions of the visual cortex, 127 as well as diminished integrity of the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus, 128 effects that were most pronounced if the person witnessed the violence before age 13.127,128 The fact that these neural alterations persist into adulthood is notable given their relevance to visual-limbic pathways connecting occipital and temporal lobes, which support vision-specific cognitive-affective processes and may maintain long-standing biases in how individuals attend to and perceive visual cues of potential threat. 126 These studies tentatively suggest potential occipital-limbic pathways in ALANA youth that may be shaped by experiences such as exposure to visual media depicting racialized violence.

Taken together, these studies suggest that clinical scientists must think carefully about how vigilance evoked by RST is conceptualized in etiological models of depression. The deleterious effects of vigilance on health are considerable and include a prioritization of safety-seeking behaviors that often get in the way of other critical aspects of daily living, as well as long-term changes in neural structures and circuitry that can influence cognitive-affective processes across the lifespan. Yet, as is true following many forms of maltreatment, vigilance can simultaneously be advantageous in some contexts. Therefore, clinical models may be best served by considering the context in which vigilance evoked by RST is manifested. For example, culturally competent interventions addressing threat appraisal might be warranted among ALANA adolescents who report difficulty discerning between contexts of high and low racism-related threat. However, even when considering the context, individual-level efforts at targeting the role of vigilance in the development of depression will not be able to fully address its impact because racism is an external factor propagated by an oppressive structure. Therefore, efforts to understand and intervene upon this target must cut across the individual and their ecological systems. 129

Measurement of Vigilance

Past research examining the role of vigilance in predicting RST and depression has largely measured vigilance using self-report questionnaires.79,116,117 For example, pioneering research from the 1995 Detroit Area Study resulted in the vigilance anticipatory coping scale, which has demonstrated validity and reliability across studies.116,117,130 Self-report assessments of vigilance carry many advantages, including face validity, reduced burden on participants, and plentiful opportunities for community input in the construction of measures. Of note, recent advances have led to sophisticated ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocols assessing racist encounters and their moment-to-moment impact on mental health. 131 Further development of EMA protocols assessing vigilance as a temporal link between symptoms of RST and depressed mood will be critical for future research.

Behavioral measures, assessed both in the laboratory and in the real-world, may shed further light on how vigilance to racism-related threat cues unfolds as a process among ALANA individuals. For example, behavioral research examining attentional vigilance within developmental models of affective disorders have historically used reaction times and eye tracking indices from computerized tasks to assess patterns of attention toward threatening images or words. 132 Modifying these paradigms to assess RST-relevant vigilance may provide opportunities to identify the types of racism-related threat stimuli that are most likely to catch the eye of ALANA youth and adults. In addition, recent technological advances have introduced opportunities to assess vigilance in the real world via wearable eye tracking goggles. 133 This technology could quantify how adolescents are attending to real-world markers of racism-related threat during lived experiences while simultaneously assessing how and when vigilance is robbing focus from other goal-oriented or hedonic pursuits. Finally, the advent of passive sensing from phones and wearable devices provides opportunities to observe vigilant behaviors (eg, avoidance of people or places) as a function of contextual factors such as location, time and date, and people present. 134 Other behaviors such as sleep, movement, phone and social media use, vocal characteristics, eye gaze, and physiology can also be extracted from wearable devices, which may allow machine-learning algorithms to detect context-specific, multimodal patterns of behavioral vigilance from data streams, 135 which could inform etiological and intervention models.

Future research may also benefit from neuroscientific assessments of vigilance, which provide important complements to self-report and behavioral measures. For example, neuroscience can offer another level of objective and precise measurement. Past research has demonstrated that precise measurement of vigilance is critical to sensitively predicting clinical outcomes;115,118 because vigilance often manifests via covert attentional processes that are not easily identifiable by behavioral indices, 136 future studies that utilize brain-based measurement [eg, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalogram (EEG)] may be able to more precisely quantify these covert processes. Additionally, neuroscientific assessments provide opportunities to map self-report or behavioral measures to discrete patterns of neural functioning. For example, as indicated by prior research,103,126 visual-frontolimbic circuits are impacted distinctly by experiencing or observing specific forms of threat. Future research is necessary to illuminate the neural pathways that may maintain vigilance following different types of racism-related threat and determine their relation to RST self-reported symptoms and behaviors, which could be used as more cost-effective markers for use in the clinic and community.

Future Directions

A review of the role of vigilance in the link between RST and risk for depression highlights many avenues for future research. First, regarding the measurement of vigilance, it is clear that a multimodal assessment of vigilance for racism-related threat is critical, as multiple levels of analysis (eg, self-report, behavioral, neural) are necessary to understand the nuanced role of vigilance in the development of depression (see Figure 1). Particularly for biobehavioral measures, future laboratory-based paradigms that assess vigilance for racism-related threat may prove more effective if they utilize idiographic and ecologically-valid threat stimuli that reflect the nature of living with racism [eg, laboratory analogs112,137], which can be achieved in part by incorporating feedback from community members and findings from qualitative research into paradigm development. Further, the measurement of vigilance in response to a wide range of racist experiences must be considered. As highlighted by this review, vigilance can follow a range of incidents, including overt discrimination, microaggressions, anticipated discrimination, vicarious discrimination (both online and off), as well as from the effects of structural racism; future research is needed to determine if there are experience-dependent patterns of vigilance that may better explain the link between RST and depression versus other forms of psychopathology. Finally, future assessments of vigilance as a link between RST and depression will benefit from repeated-measures longitudinal designs. Researchers studying both RST and developmental psychopathology have long called for more research focusing on within-person differences that emerge over time,13,138–140 as simply comparing one group of people to another at a cross-sectional time point often obfuscates important heterogeneity in lived experiences and clinical profiles. 141 Likewise, the use of between-group designs ensures that sociological conceptualizations of racism do not preclude an examination of White individuals; however, careful consideration of how metrics from ALANA youth are compared to White peers is warranted to make sure that scientists do not inadvertently support structural racism by centering the experience of White youth as the “norm”.

Clinical Implications

Research that further elucidates the potential relations between vigilance, RST, and the development of depression (particularly during critical windows such as adolescence) may have important clinical implications. First, racism-related ACEs and RST are still not widely recognized or assessed in traditional clinical care.4,34 Because clinical research is a tool that can bring attention to the experiences of marginalized communities not well represented in existing etiological or intervention models, 142 continued research on RST remains imperative. For example, in addition to refining biobehavioral models of RST, which can inform culturally competent clinical care and assessment, future use of biobehavioral indices of vigilance may provide biomarkers of racism-related harm that can be used as powerful tools in shaping public policies to improve health equity and advocating for increased mental health services for ALANA youth.

Second, etiological models examining if vigilance is a mediating link between RST and later depression may inform and support culturally competent prevention and early intervention efforts. For example, because RST is related to acute and chronic stress, mindfulness has been suggested as a potential therapeutic coping strategy to decrease anxious arousal following racial discrimination.55,143 Future research might examine whether mindfulness-based therapeutic techniques will reduce the detrimental impact of RST-induced vigilance, stress, and risk for future depression. Further development of such techniques may synergistically enhance gold standard recommendations for addressing RST in the clinic, which can include 1) facilitating a therapeutic alliance built on cultural humility, warmth, trust, safety, validation, and emotional openness, 2) creating individualized treatment plans that facilitate active and collaborative discussions of racism and lived experiences, 3) open acknowledgment of any therapist-patient shared and disparate sociocultural identities, and 4) implementation of coping strategies that emphasize social support/kinship and religiosity/spirituality.64,139,144–147 Further, given strong links between exposure to racial and ethnic discrimination and PTSD diagnoses, which are not well-addressed by Western medical guidelines for treating trauma, 23 there is a need for further inclusion of culturally emergent interventions that integrate culturally rooted practices with Western models. 148 Because RST differs from PTSD by virtue of exposure to chronic, unavoidable traumas that are woven into the structure of society, this approach ensures that the patients’ cultural identities and sociopolitical histories of oppression and collective trauma are acknowledged and integrated in treatment.

Third, research seeking to understand the role of vigilance by examining individual differences can also highlight the deep wells of resiliency that ALANA communities have fostered to promote healing outside the bounds of traditional medical systems. For example, it is possible that reductions in both self-reported and biobehavioral measurements of vigilance may occur when Black adolescents and their families engage in community-based racial socialization interventions that seek to reduce RST through supportive verbal and non-verbal communication about the positive and challenging aspects of racial identities and dynamics [ie, Anderson and colleagues’ Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) intervention149–151]. By helping to quantify existing sources of community healing, researchers can provide evidence and advocate for public policies that support autonomous community coping through additional funding and social services.

Finally, research on RST has important implications for programs that seek to dispel racism from our communities. Although a thorough description of ongoing efforts to eradicate systems that perpetuate racism is outside the scope of the current review [see 152 for a review], it is important to note that studies examining the role of vigilance may contribute to these efforts. For example, there is evidence that high quality intergroup contact (ie, social interaction between people of different races or ethnicities) can lead to a reduction in anti-Black sentiment and symbolic racism, as well as less racial profiling and stereotyping. 153 However, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated less conclusive findings, such that although contact usually reduces prejudice, contact effects vary and are weakest for interventions targeting racism. For instance, it may be that deeper engagement, rather than just casual contact, is necessary to begin to offset the interpersonal effects of racism. 154 Clearly, more research is needed to understand the active ingredients of interventions such as intergroup contact, and RST-focused research programs may offer alternative markers of efficacy that focus on quantifying the (positive or negative) impacts on ALANA individuals, in addition to the reduction of bias among dominant groups. As an example, because RST-evoked vigilance likely comes at a cost to many domains of adaptive functioning, observing reductions in self-reported and biobehavioral measures of vigilance following an intervention may indicate that it results in an interpersonal environment that allows ALANA youth and adults to thrive via reduced perception of threat.

Limitations

The current review has several limitations. First, because of a dearth of research funded to examine RST, compared to other trauma disorders, this review was unable to draw conclusions regarding whether the form and function of vigilance evoked by racism-related threats may differ based on racial or ethnic identity. This is a critical limitation as ALANA individuals are not a monolith and sociocultural identities shape lived experiences in important and unique ways. Future research is needed to compare racial and ethnic groups, as well as within-person differences, in vigilant expression. Second, this review primarily focused on racial and ethnic discrimination, which ignores the role of intersectionality in discrimination experiences. Future research and reviews are necessary to comprehensively consider how other sociocultural factors, including sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status (SES), and disability, may moderate interactions between RST, vigilance, and depression. Finally, this review focused on mechanisms underlying the development of depression and related internalizing problems, in the context of racism. However, RST is transdiagnostic risk factor for a wide range of psychopathology, including externalizing problems such as substance abuse.43–45 Notably, racial discrimination from peers in middle school is related to increased alcohol and marijuana use in high school among Black teens, 155 with “drinking to cope” identified as a common emotion-regulation strategy used across the lifespan to combat RST. 64 Future research is needed to determine if vigilance evoked by racism-related threats is a mechanism underlying strategies such as drinking to cope and a risk factor for substance use disorders.

Conclusions

In this review, we summarize evidence that vigilance evoked by racism-related threats (as observed across multiple levels of analysis) is a key mechanism underlying the link between RST and the development of depression in ALANA adolescents. We assert that research on the development of depression and other affective problems must account for the role of RST in etiological and intervention models, and, accordingly, practice must respond to this acknowledgment. Future research examining such pathways will open the door to a wide range of clinical implications, with the potential to shape intervention efforts and public policies that seek to reduce the health inequities caused by racism.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number MH119225), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, (Young Investigator Grant).

ORCID iDs: Mary L. Woody https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3021-3299

Rebecca B. Price https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7590-4325

References

- 1.Hoppen TH, Chalder T. Childhood adversity as a transdiagnostic risk factor for affective disorders in adulthood: a systematic review focusing on biopsychosocial moderating and mediating variables. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;65:81–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaVeist TA. Beyond dummy variables and sample selection: what health services researchers ought to know about race as a variable. Health Serv Res. 1994;29(1):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard DL, Calhoun CD, Banks DE, Halliday CA, Hughes-Halbert C, Danielson CK. Making the “C-ACE” for a culturally-informed adverse childhood experiences framework to understand the pervasive mental health impact of racism on black youth. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2021;14(2):233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brondolo E, Ng W, Pierre K-LJ, Lane R. Racism and mental health: Examining the link between racism and depression from a social cognitive perspective. In: Alvarez AN, Liang CTH, & Neville HA, eds. The cost of Racism for People of Color: Contextualizing Experiences of Discrimination. American Psychological Association; 2016 p. 109–132.

- 7.Bernard DL, Smith Q, Lanier P. Racial discrimination and other adverse childhood experiences as risk factors for internalizing mental health concerns among black youth. J Trauma Stress. 2022; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, Cheng Y-P. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: a meta-analytic review. American Psychologist. 2018;73(7):855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites: results from the national survey of American life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey RK, Mokonogho J, Kumar A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M. Racial/ethnic disparities in depression and its theoretical perspectives. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2014;85(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NIH. RFA-MD-21- 004: Understanding and addressing the impact of structural racism and discrimination on minority health and health disparities (R01 clinical trial optional). 2021 [Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/rfa-md-21-004.html.

- 13.Carter SE, Gibbons FX, Beach SR. Measuring the biological embedding of racial trauma among black Americans utilizing the RDoC approach. Dev Psychopathol. 2021;33(5):1849–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(1):13–105. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourabain D, Verhaeghe P-P. The conceptualization of everyday racism in research on the mental and physical health of ethnic and racial groups: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castle B, Wendel M, Kerr J, Brooms D, Rollins A. Public health’s approach to systemic racism: a systematic literature review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(1):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essed P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. In: Sage Series on Race and Ethnic Relations, 2 ed. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.López CM, Andrews AR, III, Chisolm AM, De Arellano MA, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Racial/ethnic differences in trauma exposure and mental health disorders in adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23(3):382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkins J, Briggs HE, Miller KM, Kim I, Orellana R, Mowbray O. Racial/ethnic differences in the impact of adverse childhood experiences on posttraumatic stress disorder in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2019;36(5):449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mersky J, Topitzes J, Reynolds AJ. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: a cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the US. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(11):917–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter RT, Pieterse A. Measuring the Effects of Racism: Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Race-Based Trauma-Stress Injury. Columbia University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkinis K, Pieterse AL, Martin C, Agiliga A, Brownell A. Racism, racial discrimination, and trauma: a systematic review of the social science literature. Ethn Health. 2021;26(3):392–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibrava NJ, Bjornsson AS, Pérez Benítez ACI, Moitra E, Weisberg RB, Keller MB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in African American and Latinx adults: clinical course and the role of racial and ethnic discrimination. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaylord-Harden NK, Cunningham JA. The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(4):532–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neblett EW, Jr, White RL, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyen HX, Sellers RM. Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18(3):477–515. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: a five–year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Dev. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.English D, Lambert SF, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(4):1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapee RM, Oar EL, Johnco CJ, et al. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: a review and conceptual model. Behav Res Ther. 2019;123:103501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elmore AL, Crouch E. The association of adverse childhood experiences with anxiety and depression for children and youth, 8 to 17 years of age. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):600–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balistreri KS, Alvira-Hammond M. Adverse childhood experiences, family functioning and adolescent health and emotional well-being. Public Health. 2016;132:72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jernigan MM, Daniel JH. Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: challenges and clinical implications. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2011;4(2):123–141. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders-Phillips K. Racial discrimination: a continuum of violence exposure for children of color. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12(2):174–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleem FT, Anderson RE, Williams M. Addressing the “myth” of racial trauma: developmental and ecological considerations for youth of color. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quintana SM. Racial and ethnic identity: developmental perspectives and research. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(3):259. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyer AE, Silk JS, Nelson EE. The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: from the inside out. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spears Brown C, Bigler RS. Children's perceptions of discrimination: a developmental model. Child Dev. 2005;76(3):533–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sellers RM, Copeland–Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RLH. Racial identity matters: the relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenwald R. Child Trauma Handbook: A Guide for Helping Trauma-Exposed Children and Adolescents. Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson T, Massat CR. Experiences of violence, post-traumatic stress, academic achievement and behavior problems of urban African-American children. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2005;22(5):367–393. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamblen J. PTSD in children and adolescents: A National Center for PTSD fact sheet. www.ncptsd.org. 2016. Downloaded on March 21 2022.

- 42.Gibbons FX, Roberts ME, Gerrard M, et al. The impact of stress on the life history strategies of African American adolescents: cognitions, genetic moderation, and the role of discrimination. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(3):722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter RT, Lau MY, Johnson V, Kirkinis K. Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: a meta–analytic review. J Multicult Couns Devel. 2017;45(4):232–259. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vines AI, Ward JB, Cordoba E, Black KZ. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health: a review and future directions for social epidemiology. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4(2):156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agnew R. General Strain Theory: Current Status and Directions for Further Research. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KB, eds. Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory. Routledge; 2017. p. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmerman GM, Miller-Smith A. The impact of anticipated, vicarious, and experienced racial and ethnic discrimination on depression and suicidal behavior among Chicago youth. Soc Sci Res. 2022;101:102623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassidy C, O'Connor RC, Howe C, Warden D. Perceived discrimination and psychological distress: the role of personal and ethnic self-esteem. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(3):329. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. J Adolesc. 2007;30(4):549–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: implications for group identification and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(1):135. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunte HE, King K, Hicken M, Lee H, Lewis TT. Interpersonal discrimination and depressive symptomatology: examination of several personality-related characteristics as potential confounders in a racial/ethnic heterogeneous adult sample. BMC public Health. 2013;13(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moradi B, Hasan NT. Arab American persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: the mediating role of personal control. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(4):418. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moradi B, Risco C. Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(4):411. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seaton EK, Iida M. Racial discrimination and racial identity: daily moderation among Black youth. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson RE, Stevenson HC. RECASTing racial stress and trauma: theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevenson H. RECAST Theory: Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory. In: Promoting Racial Literacy in Schools: Differences That Make a Difference. Teachers College Press; 2014. p. 113–157. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bair AN, Steele JR. Examining the consequences of exposure to racism for the executive functioning of Black students. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(1):127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy MC, Richeson JA, Shelton JN, Rheinschmidt ML, Bergsieker HB. Cognitive costs of contemporary prejudice. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2013;16(5):560–571. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borders A, Liang CT. Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miranda R, Polanco-Roman L, Tsypes A, Valderrama J. Perceived discrimination, ruminative subtypes, and risk for depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19(4):395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill LK, Hoggard LS. Active coping moderates associations among race-related stress, rumination, and depressive symptoms in emerging adult African American women. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(5):1817–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernard DL, Halliday CA, Are F, Banks DE, Danielson CK. Rumination as a mediator of the association between racial discrimination and depression among Black youth. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson TK, Gentzler AL. Emotion regulation and coping with racial stressors among African Americans across the lifespan. Dev Rev. 2021;61:100967. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polanco-Roman L, Danies A, Anglin DM. Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8(5):609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanders Thompson VL. Coping responses and the experience of discrimination 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36(5):1198–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mata-Greve F, Torres L. Ethnic discrimination, sexism, and depression among Latinx women: the roles of anxiety sensitivity and expressive suppression. Journal of Latinx Psychology. 2020;8(4):317. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination–depressive symptoms association among African American men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S2):S232–SS41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gross JT, Cassidy J. Expressive suppression of negative emotions in children and adolescents: theory, data, and a guide for future research. Dev Psychol. 2019;55(9):1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rottenberg J. Emotions in depression: what do we really know? Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:241–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism–related stress: implications for the well–being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62(4):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huynh VW, Huynh Q-L, Stein M-P. Not just sticks and stones: indirect ethnic discrimination leads to greater physiological reactivity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23(3):425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams MG, Lewis JA. Gendered racial microaggressions and depressive symptoms among Black women: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Women Q. 2019;43(3):368–380. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dale SK, Safren SA. Gendered racial microaggressions associated with depression diagnosis among Black women living with HIV. J Urban Health. 2020;97(3):377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torres L, Taknint JT. Ethnic microaggressions, traumatic stress symptoms, and Latino depression: a moderated mediational model. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(3):393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Auguste EE, Cruise KR, Jimenez MC. The effects of microaggressions on depression in young adults of color: investigating the impact of traumatic event exposures and trauma reactions. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(5):985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, Hamati MC, Dominguez TP. Transmitting trauma: a systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chae DH, Yip T, Martz CD, et al. Vicarious racism and vigilance during the COVID-19 pandemic: mental health implications among Asian and Black Americans. Public Health Rep. 2021:136(4):508–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.English D, Lambert SF, Tynes BM, Bowleg L, Zea MC, Howard LC. Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black US American adolescents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2020;66:101068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heard-Garris NJ, Ekwueme PO, Gilpin S, et al. Adolescents’ experiences, emotions, and coping strategies associated with exposure to media-based vicarious racism. JAMA network Open. 2021;4(6):e2113522–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keum BT. Qualitative examination on the influences of the internet on racism and its online manifestation. International journal of cyber behavior Psychology and Learning (IJCBPL. 2017;7(3):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of Black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tynes BM, Willis HA, Stewart AM, Hamilton MW. Race-related traumatic events online and mental health among adolescents of color. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;65(3):371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tynes BM, Giang MT, Williams DR, Thompson GN. Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(6):565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eichstaedt JC, Sherman GT, Giorgi S, et al. The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George Floyd on the US population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(39):e2109139118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller HN, LaFave S, Marineau L, Stephens J, Thorpe RJ, Jr. The impact of discrimination on allostatic load in adults: an integrative review of literature. J Psychosom Res. 2021;146:110434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:201–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brondolo E, Libby DJ, Denton E-g, et al. Racism and ambulatory blood pressure in a community sample. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:407–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simons RL, Lei M-K, Klopack E, Zhang Y, Gibbons FX, Beach SR. Racial discrimination, inflammation, and chronic illness among African American women at midlife: support for the weathering perspective. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(2):339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brody GH, Lei MK, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SR. Perceived discrimination among African A merican adolescents and allostatic load: a longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Dev. 2014;85(3):989–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brody GH, Yu T, Beach SR. Resilience to adversity and the early origins of disease. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(4pt2):1347–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meyer CS, Schreiner PJ, Lim K, Battapady H, Launer LJ. Depressive symptomatology, racial discrimination experience, and brain tissue volumes observed on magnetic resonance imaging: the CARDIA study. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(4):656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fani N, Harnett NG, Bradley B, et al. Racial discrimination and white matter microstructure in trauma-exposed Black women. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91(3):254–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clark US, Miller ER, Hegde RR. Experiences of discrimination are associated with greater resting amygdala activity and functional connectivity. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2018;3(4):367–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Simons RL, Lei M-K, Klopack E, Beach SR, Gibbons FX, Philibert RA. The effects of social adversity, discrimination, and health risk behaviors on the accelerated aging of African Americans: further support for the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 2021;282:113169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carter SE, Ong ML, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Lei MK, Beach SR. The effect of early discrimination on accelerated aging among African Americans. Health Psychol. 2019;38(11):1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Price RB, Duman R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(3):530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Price RB, Woody ML. Emotional disorders in development. In: Della Sala S, ed. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience. 2 ed. Elsevier Science; 2021: p. 364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Norrholm SD, Glover EM, Stevens JS, et al. Fear load: the psychophysiological over-expression of fear as an intermediate phenotype associated with trauma reactions. Int J Psychophysiol. 2015;98(2):270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fani N, Carter SE, Harnett NG, Ressler KJ, Bradley B. Association of racial discrimination with neural response to threat in Black women in the US exposed to trauma. JAMA psychiatry. 2021;78(9):1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alexandra Kredlow M, Pineles SL, Inslicht SS, et al. Assessment of skin conductance in African American and non–African American participants in studies of conditioned fear. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(11):1741–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harnett NG, Wheelock MD, Wood KH, et al. Negative life experiences contribute to racial differences in the neural response to threat. Neuroimage. 2019;202:116086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Webb EK, Weis CN, Huggins AA, et al. Neural impact of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage in traumatically injured adults. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;15:100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Neblett EW, Jr. Racism and health: challenges and future directions in behavioral and psychological research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2019;25(1):12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hope EC, Brinkman M, Hoggard LS, et al. Black adolescents’ anticipatory stress responses to multilevel racism: the role of racial identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2021;91(4):487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Armstead CA, Lawler KA, Gorden G, Cross J, Gibbons J. Relationship of racial stressors to blood pressure responses and anger expression in Black college students. Health Psychol. 1989;8(5):541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kort DN. We can’t breathe: Affective and psychophysiological reactivity of vicarious discrimination 2016.

- 111.Volpe VV, Lee DB, Hoggard LS, Rahal D. Racial discrimination and acute physiological responses among Black young adults: the role of racial identity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;64(2):179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jones DR, Harrell JP, Morris-Prather CE, Thomas J, Omowale N. Affective and physiological responses to racism: the roles of Afrocentrism and mode of presentation. Ethn Dis. 1996;6(1–2):109–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Neblett EW, Jr, Roberts SO. Racial identity and autonomic responses to racial discrimination. Psychophysiology. 2013;50(10):943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sawyer PJ, Major B, Casad BJ, Townsend SS, Mendes WB. Discrimination and the stress response: psychological and physiological consequences of anticipating prejudice in interethnic interactions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.McLaughlin KA, Colich NL, Rodman AM, Weissman DG. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. 2020;18(96):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Pierre G, Mance GA, Williams DR. The relationships among vigilant coping style, race, and depression. J Soc Issues. 2014;70(2):241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Himmelstein MS, Young DM, Sanchez DT, Jackson JS. Vigilance in the discrimination-stress model for Black Americans. Psychol Health. 2015;30(3):253–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Woody ML, Price RB. Targeting neurodevelopmental mechanisms in emotional disorders through intervention. In: Sala SD, ed. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience. 2 ed. Elsevier Science; 2021: p. 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Masten CL, Telzer EH, Eisenberger NI. An fMRI investigation of attributing negative social treatment to racial discrimination. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23(5):1042–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(2):113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Coogan P, Schon K, Li S, Cozier Y, Bethea T, Rosenberg L. Experiences of racism and subjective cognitive function in African American women. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2020;12(1):e12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Levy DJ, Heissel JA, Richeson JA, Adam EK. Psychological and biological responses to race-based social stress as pathways to disparities in educational outcomes. American Psychologist. 2016;71(6):455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brown TH. Trauma-related sleep disturbance in youth. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;34:128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Silk JS, Davis S, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Forbes EE. Why do anxious children become depressed teenagers? The role of social evaluative threat and reward processing. Psychol Med. 2012;42(10):2095–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K. The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(10):652–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tomoda A, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Teicher MH. Reduced visual cortex gray matter volume and thickness in young adults who witnessed domestic violence during childhood. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e52528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Choi J, Jeong B, Polcari A, Rohan ML, Teicher MH. Reduced fractional anisotropy in the visual limbic pathway of young adults witnessing domestic violence in childhood. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1071–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological Systems Theory. In: Vasta R (ed), Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1992: p. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Clark R, Benkert RA, Flack JM. Large arterial elasticity varies as a function of gender and racism-related vigilance in Black youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(4):562–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Joseph NT, Peterson LM, Gordon H, Kamarck TW. The double burden of racial discrimination in daily-life moments: increases in negative emotions and depletion of psychosocial resources among emerging adult African Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2021;27(2):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rosen D, Price RB, Silk JS. An integrative review of the vigilance-avoidance model in pediatric anxiety disorders: are we looking in the wrong place? J Anxiety Disord. 2019;64:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pérez-Edgar K, MacNeill LA, Fu X. Navigating through the experienced environment: insights from mobile eye-tracking. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2020;29(3):286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Morris ME, Aguilera A. Mobile, social, and wearable computing and the evolution of psychological practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43(6):622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Silk JS. Context and dynamics: the new frontier for developmental research on emotion regulation. Dev Psychol. 2019;55(9):2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Weierich MR, Treat TA, Hollingworth A. Theories and measurement of visual attentional processing in anxiety. Cognition and Emotion. 2008;22(6):985–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Harrell JP, Hall S, Taliaferro J. Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: an assessment of the evidence. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jones SC, Anderson RE, Gaskin-Wasson AL, Sawyer BA, Applewhite K, Metzger IW. From “crib to coffin”: navigating coping from racism-related stress throughout the lifespan of Black Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90(2):267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Neblett EW, Jr, Sosoo EE, Willis HA, Bernard DL, Bae J, Billingsley JT. Racism, racial resilience, and African American youth development: person-centered analysis as a tool to promote equity and justice. Adv Child Dev Behav. 2016;51:43–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Molenaar PC, Campbell CG. The new person-specific paradigm in psychology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(2):112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Carnethon MR, Kershaw KN, Kandula NR. Disparities research, disparities researchers, and health equity. JAMA. 2020;323(3):211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Graham JR, West LM, Roemer L. The experience of racism and anxiety symptoms in an African-American sample: moderating effects of trait mindfulness. Mindfulness (N Y). 2013;4(4):332–341. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Day–Vines NL, Cluxton–Keller F, Agorsor C, Gubara S. Strategies for broaching the subjects of race, ethnicity, and culture. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2021;99(3):348–357. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pieterse AL. Attending to racial trauma in clinical supervision: enhancing client and supervisee outcomes. Clin Superv. 2018;37(1):204–220. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Jones SC, Anderson RE, Metzger IW. “Standing in the gap”: the continued importance of culturally competent therapeutic interventions for Black youth. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2020;5(3):327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Neblett EW, Jr, Sosoo EE, WilliS HA, Bernard DL, Bae J. Cognitive behavioral models, measures, and treatments for depressive disorders in African Americans. 2018.

- 148.Bryant-Davis T. The cultural context of trauma recovery: considering the posttraumatic stress disorder practice guideline and intersectionality. Psychotherapy. 2019;56(3):400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Anderson RE, McKenny M, Mitchell A, Koku L, Stevenson HC. EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: preliminary feasibility and coping responses of a racial socialization intervention. Journal of Black Psychology. 2018;44(1):25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Anderson RE, McKenny MC, Stevenson HC. EMBR Ace: developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among Black parents and adolescents. Fam Process. 2019;58(1):53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Anderson RE, Metzger I, Applewhite K, et al. Hands up, now what?: Black Families’ reactions to racial socialization interventions. J Youth Dev. 2020;15(5):93–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]