Abstract

Background and objectives

Postpartum depression affects women, manifesting with depressed mood, insomnia, psychomotor retardation, and suicidal thoughts. Our study examined if there is an association between epidural analgesia use and postpartum depression.

Methods

Patients were divided into two groups. One group received epidural analgesia during labor while the second group did not. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) was administered to patients prior to birth and 6 weeks postpartum. Pain severity was assessed by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) during labor and at 24 hours postpartum.

Results

Of the 92 patients analyzed, 47.8% (n = 44) received epidural analgesia. We detected significantly higher VAS score during labor (p = 0.007) and 24 hours postpartum (p = 0.0001) in the group without epidural analgesia. At 6 weeks postpartum, a significant difference was observed between the EPDS scores of both groups (p = 0.0001). Regression analysis revealed higher depression scores in patients experiencing higher levels of pain during labor (OR = 0.572, p = 0.039). Epidural analgesia strongly correlated with lower scores of depression (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0001).

Conclusion

The group that received epidural analgesia had lower pain scores. A high correlation between epidural analgesia and lower depression levels was found. Pregnant women giving birth via the vaginal route and having high pain scores could reduce postnatal depression scores using epidural labor analgesia. Pregnant women should opt for epidural analgesia during labor to lessen postpartum depression levels.

Keywords: Postpartum depression, Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, Epidural analgesia, Visual Analogue Scale, Vaginal birth

Introduction

Currently, increasing the rates of vaginal deliveries is the focus of attention because giving birth by the vaginal route is one of the most important factors associated with both maternal and infant health.1, 2 Unfortunately, vaginal delivery is not completely free of complications, such as its association with postpartum depression.3 Postpartum depression, manifested as a depressed mood, insomnia or somnolence, marked weight loss, psychomotor retardation, a lowered self-esteem and self-worth, and suicidal thoughts is a disorder of pregnant women after giving birth.3, 4 The incidence of postpartum depression may be as high as 1 in every 10 postpartum women in developed countries.5 Postpartum depression may lead to behavioral and developmental problems both in the mother and the infant, and those problems may extend into childhood and adolescence periods.6

Among women who deliver vaginally, a number prefer to receive epidural analgesia for delivery while some do not. Epidural analgesia is commonly used to alleviate pain during labor and is well tolerated by both the mother and the infant. Several studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that epidural analgesia is an effective method to reduce the severity of pain during normal vaginal delivery.7 However, there are only a few studies in the literature investigating the effect of epidural labor analgesia on postpartum depression which reported a decreased risk of postpartum depression with epidural labor analgesia.4

In this study, our primary hypothesis was that women who had epidural labor analgesia would have lower depression severity scores 6 weeks postpartum. Our secondary hypothesis was that those patients would have lower Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores during labor and 24 hours postpartum if they received epidural analgesia.

Methods

Our study is a prospective observational study over a 6-month period. The institutional ethics committee of the Istanbul Education and Research Hospital's Anesthesiology Department approved this study. It is registered via the ISRCTN registry with study ID ISRCTN84174861 (recruitment start date of March 25, 2018 and recruitment end date of October 25, 2018). Women aged 18-45 years, who were planning to give birth electively via a normal vaginal route with or without epidural analgesia, with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-III, and who consented to participate were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had a history of schizophrenia, bipolar or obsessive-compulsive disorders in the prepartum period, if they had any hematological disorders that contraindicated use of regional anesthesia, and if they had skin infections in the lumbar area or inadequate fetal vitality concepts. Patients were also excluded if the route of delivery was switched to a cesarean section or have prepartum depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale ≥ 10).

Upon admission to our hospital, when patients met the criteria of inclusion, informed consent was obtained from each patient in the waiting room and they were allocated to one of the two groups. Initially we used “patient preference” for the decision of the technique. But for patients who have contraindications for regional anesthesia, we informed and inclined the patient for the indicated approach (infection in the intervention site, bleeding, pathologies, and intracranial disorders were our contraindications for epidural analgesia). One group consisted of women who gave birth without receiving epidural analgesia and the second group consisted of women who gave birth with epidural analgesia. The second group received an epidural catheter, placed in the intervertebral space between either L3–L4 or L4–L5, when cervical dilatation of the patient reached 3–5 cm, while the other group received no intervention for their labor. Patients in the epidural analgesia group received a bolus dose of bupivacaine 0.125% + 100 μg fentanyl via the epidural catheter. This was followed by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) containing 0.125% bupivacaine + 2 μg.mL-1 fentanyl with 6 ml.h-1 continuous infusion and 6 ml PCA demand dose with 10-minute lockouts. Prior to birth and 6 weeks postpartum, an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was administered to both patient groups. The EPDS is a commonly used 10-item scale validated for our study population. A score ≥ 10 was the cut-off score for postpartum depression. If a patient responded positively to item 10 (the thought of harming myself has occurred to me) of the EPDS, they were evaluated for overt depression regardless of the patient’s total score and were reported to our hospital’s psychiatric department. EPDS were applied by the same experienced anesthesiologist. Both groups received postpartum analgesia. One group received epidural PCA containing the previously started dose (0.125% bupivacaine + 2 μg.mL-1 fentanyl with 6 ml.h-1 continuous infusion and 6 ml PCA demand dose with 10-minute lockouts) until discharge. The second group received intravenous (IV) tramadol 1 mg.kg-1 twice a day and 15 mg.kg-1 paracetamol three times a day as well as rescue tramadol doses of 1 mg.kg-1 if necessary, until discharge. The patient’s severity of the pain was assessed by the VAS during the birth and 24 hours postpartum. In the VAS, the lowest score is 0 (no pain at all) and the highest is 10 (worst pain imaginable). The aim was to keep patient VAS scores below 4. We recorded demographic parameters, gestational age, number of pregnancies, VAS scores, and EPDS scores.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 21.0 software was used for the statistical analysis. The study data were summarized with the descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, frequency, and ratio). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for inter-group comparisons of quantitative data not conforming to a normal distribution. The correlation between the use of epidural labor analgesia, VAS score, and occurrence of postpartum depression was assessed with multivariate logistic regression analysis. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used for the logistic regression model. Qualitative data was compared with the Student’s t test. Results were evaluated in a confidence interval of 95% and at a significance level of p < 0.05. The Power and Sample Size program (PS version 3.1.2) was used for patient number analysis. If the change in the EPDS was assumed to be at least 20%,4 the lowest number of patients to be included in the study should be 88 to meet an α = 0.05 and a power = 0.80. It was assumed that there would be a high number of drop-outs in the study, therefore we planned to include 127 patients at baseline.

Results

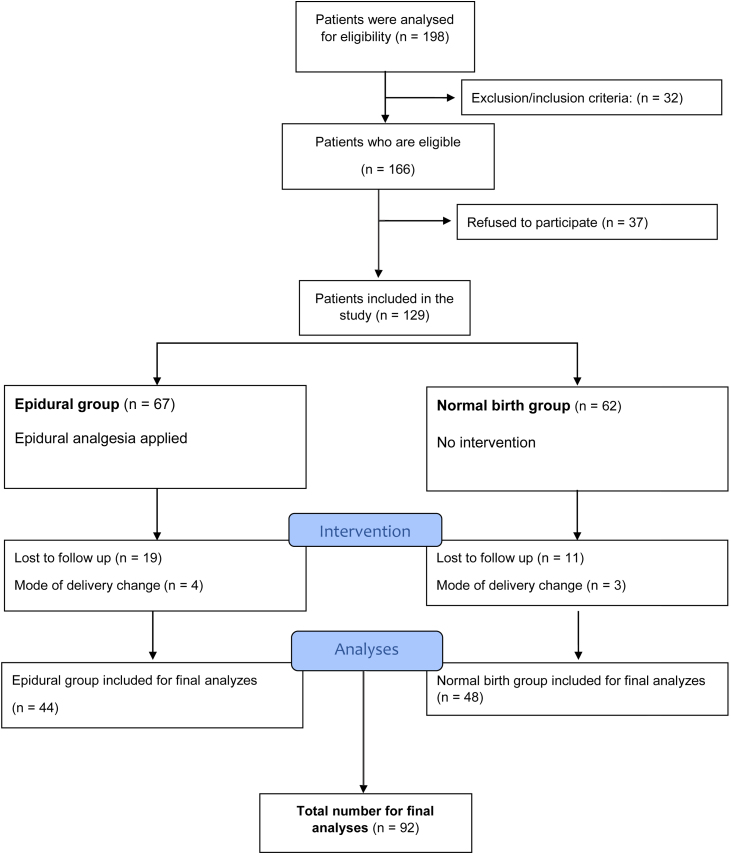

Of the 198 patients analyzed for eligibility, 166 were found eligible according to the exclusion/ inclusion criteria. Among these 166 eligible patients, 129 patients gave consent and participated in the study. After excluding patients lost to follow-up and change of delivery, 92 patients were analyzed in the final evaluation (Fig. 1). Of these 92 patients, 47.8% (n = 44) preferred delivery with epidural analgesia. The remaining patients did not receive epidural analgesia. The mean age of the patients was 29.81 ± 7.19 years. The demographic data of the study patients are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram. A comparison of the severity of postpartum depression in women who gave normal vaginal birth with or without epidural analgesia.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Data.

| Epidural analgesia group | 47.8% (n = 44) |

| Age (years) | 29.81 ± 7.19 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 28.24 ± 4.39 |

| Gestation (weeks) | 38.47 ± 0.79 |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.88 ± 1.16 |

| VAS score during labor | 5.58 ± 2.52 |

| VAS 24 hours postpartum | 4.17 ± 2.18 |

| Prepartum EPDS scores | 8.32 ± 4.66 |

| EPDS score 6 weeks postpartum | 6.08 ± 4.58 |

| ASA score | |

| II | 60 (64.5%) |

| III | 32 (34.4%) |

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

No statistically significant differences in patient demographics were detected between the epidural labor analgesia group and the group who did not receive epidural analgesia (p > 0.05). These data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of the demographic data between the two groups.

| Epidural analgesia (n = 44) |

No epidural analgesia (n = 48) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.88 ± 6.81 | 30.64 ± 7.49 | 0.243 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 28.07 ± 4.12 | 28.4 ±4.65 | 0.723 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.43 ± 0.72 | 38.52 ± 0.85 | 0.593 |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.28 ± 0.48 | 2.31 ± 1.33 | 0.076 |

| ASA score | |||

| II | 29 (65.9%) | 31 (64.5%) | 0.894 |

| III | 15 (34.1%) | 17 (35.5%) |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status. Mann–Whitney U test and Student’s t test were used.

p < 0.05 was determined statistically significant.

In the group of women who gave birth without epidural analgesia, we detected significant differences in the VAS scores both during labor (p = 0.0001) and 24 hours after delivery (p = 0.007). Overall, we report that the women giving birth with epidural analgesia experienced significantly lower pain levels (Table 3). There was not a significant difference in the EPDS scores between the groups in the prepartum period (p = 0.191); however, we detected a high degree of significant difference in the EPDS scores 6 weeks postpartum between the two groups (p = 0.0001). Therefore, postnatal depression score was lower among women who received epidural analgesia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of VAS and EPDS scores between groups.

| Epidural analgesia (n = 44) |

No epidural analgesia (n = 48) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS score during labor | 3.28 ± 0.95 | 7.21 ± 1.93 | 0.0001a |

| VAS score 24 hours postpartum | 2.71 ± 0.82 | 5.30 ± 2.26 | 0.007a |

| Prepartum EPDS score | 7.63 ± 4.72 | 8.91 ± 4.58 | 0.191 |

| EPDS score 6 weeks postpartum | 3.89 ± 3.43 | 8.08 ± 4.61 | 0.0001a |

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status. Mann–Whitney U test and Student’s t test were used.

p < 0.05 was determined statistically significant.

Multiple regression analysis (Table 4) revealed that EPDS scores correlated with receiving epidural analgesia during labor and with VAS scores during delivery. Higher scores of depression were found in patients experiencing higher levels of pain during labor (OR = 0.572, p = 0.039). This finding was not detected 24 hours postpartum in VAS scores. In addition, women who received epidural analgesia had lower scores of depressions (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of EPDS scores.

| Odds Ratio (OR) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| VAS score 24 hours postpartum | 0.288 | 0.117 |

| VAS score at labor | 0.572 | 0.039* |

| Epidural analgesia | 0.290 | 0.0001* |

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

An EPDS score ≥ 10 equals depression.

The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used for the logistic regression model.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationship between epidural analgesia and depression score in women who gave birth vaginally. The EPDS, which is widely used and validated, was selected to assess the probability of depression in the women included in the study.8, 9 This scale has also been validated for the pregnant patient population in our country.10 We observed that pain severity was significantly higher in the women who did not prefer to receive epidural analgesia during labor, with significantly higher VAS scores in both the prepartum and postpartum periods. Logistic regression analysis identified that the VAS score at labor was correlated with the development of postnatal depression (OR = 0.572, p = 0.039). We report a very high correlation between the use of epidural analgesia and lower postpartum depression levels (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0001).

In a recent study, Lim et al. reviewed a total of 201 patients retrospectively and reported that alleviation of labor pain with epidural analgesia resulted in a reduction in the severity of depression symptoms.6 We reported similar results in this observational and prospective study.

Again, similar to our results, Ding et al. reported an association between epidural analgesia and decreased severity of depression in a study including 200 individuals.4 We additionally evaluated patient depression levels both before labor and in the postpartum period. In our study, there was no difference in depression levels between the two groups prior to labor, however, there was a significant difference in the EPDS scores 6 weeks postpartum (p = 0.0001). Regression analysis demonstrated the correlation between the epidural analgesia and depression effectively. A study performed by Badou et al. with 43 patients was the first to demonstrate an association between the severity of labor pain and depression.11 Contrary, some studies were unable to detect a relationship between depression and labor pain severity. Our study is in line with that published by Badou et al. We believe the discrepancy in outcomes are due to insufficient data regarding pain scores.4

There are a wide range of studies in the literature investigating the outcomes of postpartum depression on both mother and infant. One study investigated patients who underwent a cesarean section and those who delivered vaginally, and they suggested a significant relationship between severe pain and postpartum depression.12 They also reported that postpartum depression may be responsible for 17% of late-phase maternal deaths.12 In addition to those studies, a number of studies in the literature report that postpartum depression adversely affected nursing the infant.13, 14 In their study including 2,729 patients, Verbeek et al. reported that postpartum depression affected the childhood period unfavorably. Furthermore, they added that those effects may be so extensive that they negatively influence the adolescent period.15 These findings lead to the conclusion that postpartum depression is a major cause of morbidity in women and attempts to lower its incidence rate are needed.

In our current study, we report that the VAS score 6 weeks postpartum was correlated with development of postnatal depression. Several studies, available in the literature, report similar results to those of our study in which administration of epidural analgesia resulted in a significant reduction in VAS scores.16, 17, 18 We believe that epidural analgesia is the main determinant for pain reduction and lower VAS scores. We also assume that this reduction in pain was one of the most important factors creating the correlation between epidural analgesia and lower postpartum depression rates.

On the other hand, other studies report that epidural analgesia in pregnant women cause unfavorable or contradicting results. In a meta-analysis including 9,658 patients, Anim et al. reported results different from those summarized above.7 They found that women who received an epidural mode of administration experienced more hypotension compared to women that did not.7, 19, 20, 21 Other studies also reported that epidural modes of administration caused a delay in the second phase of labor.7, 22, 23 Although epidural analgesia allows for better pain control, the authors could not demonstrate significant differences in the levels of maternal satisfaction, reporting that there were some contradicting findings.7

The limitations of our study are the low number of pregnant women included. Increasing the number of patients would maybe enhance the value of our findings. Another limitation is that VAS scores are a subjective means of assessment for pain. However, a more effective scoring system for pain assessment is not available. Therefore, the VAS is commonly used in the literature. One of the best ways of evaluating postoperative pain is the opioid consumption of the patient but we could not use this approach because of the different methods of analgesia for postpartum period. Also, there are other confounding factors that may influence the chance of postpartum depression like patients’ socioeconomic class and postpartum BMI at the time of the second evaluation but we did not investigate these variables and this is another limitation for our study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found an association between favorable VAS scores and lower depression severity 6 weeks postpartum in women who received epidural analgesia and gave birth vaginally. In addition, we report that increased scores of pain at labor were correlated with postpartum depression score and there was a very high correlation with the use of epidural analgesia and lower depression levels. In light of these results, we suggest that pregnant women giving birth via the vaginal route should use analgesia.

Trial registry

Our study was registered February 15, 2016 via the ISRCTN registry with study ID ISRCTN84174861.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care: A Handbook. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayrampour H., Salmon C., Vinturache A., et al. Effect of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy on risk of obstetric interventions. J. Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:1040–1048. doi: 10.1111/jog.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association . 4th edition; text revision. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding T., Wang D.X., Qu Y., et al. Epidural Labor Analgesia Is Associated with a Decreased Risk of Postpartum Depression: A Prospective Cohort Study. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:383–392. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orbach-Zinger S., Landau R., Harousch A.B., et al. The Relationship Between Women’s Intention to Request a Labor Epidural Analgesia, Actually Delivering With Labor Epidural Analgesia, and Postpartum Depression at 6 Weeks: A Prospective Observational Study. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1590–1597. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim G., Farrell L.M., Facco F.L., et al. Labor Analgesia as a Predictor for Reduced Postpartum Depression Scores: A Retrospective Observational Study. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1598–1605. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anim-Somuah M., Smyth R.M., Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanardo V., Giliberti L., Volpe F., et al. Cohort study of the depression, anxiety, and anhedonia components of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale after delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:277–281. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthey S., Souter K., Mortimer K., et al. Routine antenatal maternal screening for current mental health: evaluation of a change in the use of the Edinburgh Depression Scale in clinical practice. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0570-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aksu S., Varol F.G., Hotun Sahin N. Long-term postpartum health problems in Turkish women: prevalence and associations with self-rated health. Contemporary Nurse. 2017;53:167–181. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1258315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boudou M., Teissèdre F., Walburg V., et al. Association between the intensity of childbirth pain and the intensity of postpartum blues. Encephale. 2007;33:805–810. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenach J.C., Pan P.H., Smiley R., et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dias C.C., Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. Affect Disord. 2015;171:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueiredo B., Canário C., Field T. Breast feeding is negatively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartum depression. Psychol.Med. 2014;43:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verbeek T., Bockting C.L., van Pampus M.G., et al. Postpartum depression predicts offspring mental health problems in adolescence independently of parental lifetime psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugliese P.L., Cinnella G., Raimondo P., et al. Implementation of epidural analgesia for labor: is the standard of effective analgesia reachable in all women? An audit of two years. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:1262–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sikdar I., Singh S., Setlur R., et al. A prospective review of the labor analgesia programme in a teaching hospital. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69:361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweed N., Sabry N., Azab T., et al. Regional versus IV analgesics in labor. Minerva Med. 2011;102:353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Kerdawy H., Farouk A. Labor analgesia in preeclampsia: remifentanil patient controlled intravenous analgesia versus epidural analgesia. Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology. 2010;20:539–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Head B., Owen J., Vincent R., et al. A randomized trial of intrapartum analgesia in women with severe preeclampsia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2002;99:452–457. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01757-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambling D.R., Sharma S.K., Ramin S.M., et al. A randomized study of combined spinal epidural analgesia versus intravenous meperidine during labor: impact on cesarean delivery rate. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1336–1344. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199812000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lian Q., Ye X. The effects of neuraxial analgesia of combination of ropivacaine and fentanyl on uterine contraction. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:A1332. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long J., Yue Y. Patient controlled intravenous analgesia with tramadol for pain relief. Chinese Medical Journal. 2003;116:1752–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]