Abstract

Background and objectives

Neuraxial hematoma is a rare complication of the epidural technique which is commonly used for high quality postoperative pain relief. In case of urgent initiation of multiple antithrombotic therapy, the optimal timing of epidural catheter removal and need for treatment modification may be quite challenging. There are no specific guidelines and published reports are scarce.

Case report

We present the uneventful removal of an indwelling epidural catheter in a patient who was put on emergency triple antithrombotic treatment with Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH), aspirin and clopidogrel in the immediate postoperative period, due to acute coronary syndrome. In order to define the optimal conditions and timing for catheter removal, so as to reduce the risk of complications, various laboratory tests were conducted 3 hours after aspirin/clopidogrel intake. Standard coagulation tests revealed normal platelet count, normal prothrombin time and normal activated partial thromboplastin time, while Platelet Function Analysis (PFA-200) revealed abnormal values (increased COL/EPI and COL/ADP values, both indicating inhibition of platelet function). The anti-Xa level, estimated 4 hours after LMWH administration, was within therapeutic range. At the same time, Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM) showed a relatively satisfactory coagulation status overall. The epidural catheter was removed 26 hours after the last dual antiplatelet dose and the next dose was given 2 hours after removal. Enoxaparin was withheld for 24 hours and was resumed after 6 hours. Neurologic checks were performed regularly for alarming signs and symptoms suggesting development of an epidural hematoma. No complications occurred.

Conclusion

Point-of-care coagulation and platelet function monitoring may provide a helpful guidance in order to define the optimal timing for catheter removal, so as to reduce the risk of complications. A case-specific management plan based on a multidisciplinary approach is also important.

Keywords: Epidural anesthesia, Platelet aggregation inhibitors, Anticoagulants, Blood coagulation tests

Introduction

Neuraxial hematoma is a rare complication of the epidural technique which is commonly used for postoperative analgesia. It usually occurs after epidural catheter removal and may have disastrous neurologic consequences.1, 2 In case of urgent multiple antithrombotic treatment, appropriate timing for epidural catheter removal is not clearly defined by guidelines and remains challenging.

We describe the uneventful removal of an epidural catheter in a patient who was put on emergency triple antithrombotic treatment in the immediate postoperative period. For the presentation of this case, written informed consent was obtained from the patient and the CARE guidelines were followed.

Case report

A 78-year-old male patient (166 cm, 74 kg) was scheduled for pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) for pancreatic cancer. His medical history included coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Platelet count and standard coagulation tests were normal.

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia combined with epidural analgesia; preoperatively, a 20G epidural catheter was inserted through an 18G Tuohy needle at the level of T9–T10 interspace. The procedure was very extensive and prolonged (9 hours), including total pancreatectomy, splenectomy, and portal vein reconstruction. It was associated with massive blood loss and transfusion of blood products, hemodynamic instability, and circulatory support with vasoactive agents. Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and was put on unfractionated heparin 7500 units/12 h as anticoagulation for the portal vein reconstruction.

The following day, T-wave inversion was observed on the electrocardiogram, along with elevation of the high sensitive Troponin-I (hsTnI peak of 8,496 pg.mL−1, normal values < 34.2 pg.mL−1) and decrease of patient's ejection fraction (from 45% to 30%). The diagnosis of a non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction was made, and emergency dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg) was added to heparin. The patient developed frequent episodes of ventricular tachycardia for which a cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted. On the 6th postoperative day (POD-6), the unfractionated heparin was replaced by Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH), namely enoxaparin 6,000 IU/12 h.

On POD-10, a multidisciplinary medical team (anesthesiologist, cardiologist, hematologist, surgeon) considered the possibility to remove the epidural catheter after weighing the risks and informing the patient and his family. The ongoing triple antithrombotic therapy raised serious concerns regarding potential bleeding complications following catheter removal, but the patient's critical condition would not allow discontinuation of antithrombotic drugs.

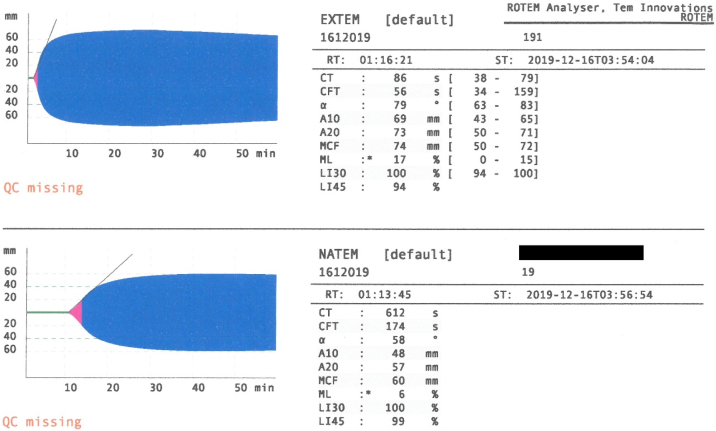

Laboratory tests were conducted 3 hours after aspirin/clopidogrel intake and showed a normal platelet count (291,900 μL-1, reference values: 150,000–400,000 μL-1), normal Prothrombin and activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (PT = 12.6 s, aPTT = 34 s, reference values PT = 11–15 s, aPTT = 24–40 s). Platelet function analysis (Platelet function Assay, PFA-200) revealed abnormal values with both agonists COL-EPI > 248 s and COL-ADP > 235 s (reference values < 150 s and <100 s, respectively). The anti-Xa level, estimated 4 hours after LMWH administration, was within therapeutic range (1.32 IU.mL−1, local therapeutic reference range: 0.51–1.47 IU.mL−1). At the same time, Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM™, Pentapharm, Munich, Germany) showed a relatively satisfactory coagulation status overall (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thromboelastogram obtained by Rotational Thromboelastography (ROTEM). The NATEM was normal with a Clotting Time (CT) of 612 seconds (normal values: 300–999 s), a Clot Formation Time (CFT) of 174 seconds (normal values: 150–700 s), an alpha of 58 (normal values: 30–70), and a Maximum Clot Firmness (MCF) of 60 mm (normal values: 40–65 mm). The EXTEM revealed a Clotting Time (CT) of 86 seconds (normal values: 38–79 s), a Clot Formation Time (CFT) of 56 seconds (normal 34–159 s), an alpha of 79 (normal values: 63–83), and a Maximum Clot Firmness (MCF) of 74-mm (normal values: 50–72 mm).

The plan was to repeat the PFA on POD-11, at least 24 hours after aspirin/clopidogrel, just before catheter removal. Unfortunately, that was not possible due to technical reasons. Finally, the epidural catheter was removed 26 hours after the last dual antiplatelet dose and the next dose was given 2 hours after removal. Enoxaparin had been withheld for 24 hours and was resumed after 6 hours. Neurologic checks were performed regularly for alarming signs and symptoms suggesting development of an epidural hematoma. No complications occurred.

Discussion

The overall incidence of neuraxial hematoma is about 1:150,000 epidurals, but the risk increases significantly in patients receiving combination therapy with antiplatelets, anticoagulants and/or thrombolytics.1, 2 Epidural hematomas usually occur after epidural catheter removal and may lead to permanent neurologic deficits.2 The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) recommends that clopidogrel should be discontinued 5–7 days prior to neuraxial procedures and can be resumed immediately, provided that a loading dose is omitted.2 There are no restrictions for aspirin.2 In patients receiving therapeutic doses of LMWH b.i.d., an indwelling catheter should be removed at least 24 hours after the last dose, while LMWH can be resumed 4 hours after catheter removal.2 However, in the context of emergency combined therapy with anticoagulants/antiplatelets, discontinuation of treatment could be life-threatening.2

There are no specific guidelines regarding neuraxial catheter handling in patients receiving multiple antithrombotics, while published reports are scarce.3, 4, 5 In a patient under single antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel 75 mg) and enoxaparin (30 mg b.i.d.) for acute coronary syndrome, Thromboelastography (TEG) showed hypercoagulability without platelet dysfunction; the in-situ epidural catheter was removed 12 hours after enoxaparin dose without clopidogrel discontinuation.3

In another report, the authors were more conservative with a patient who received accidentally one single dose of clopidogrel 75 mg/aspirin 325 mg while being on enoxaparin 90 mg b.i.d. Conventional coagulation tests, platelet function analysis and TEG were normal, and catheter was removed 72 hours after antiplatelets and 24 hours after enoxaparin.4

In a more complicated case, similar to ours, the patient underwent urgent postoperative coronary stenting and was put on dual antiplatelet therapy combined with unfractionated heparin infusion.5 The epidural catheter was removed 24 hours after the last aspirin/clopidogrel dose and 4 hours after discontinuation of unfractionated heparin infusion. Removal was guided by ROTEM which showed normal coagulation and by impedance aggregometry (Multiple Platelet Function Analyzer) at 2 and 24 hours after antiplatelet intake, which demonstrated partial recovery of platelet function over time.5

Our patient was under intensive triple antithrombotic therapy with clopidogrel, aspirin and LMWH. We performed a global hemostatic assessment via PT, aPTT, PFA200, anti-Xa and ROTEM close to the time of peak levels of all antithrombotic agents. Although platelet count was normal, platelet function assays performed close to aspirin/clopidogrel administration revealed inhibition of platelet function (increased COL/EPI and COL/ADP values). ROTEM, disclosed a satisfactory clot quality formation ability, when referring to maximum clot formation, despite a subtle prolongation in clot formation time, which was, however, not clinically evaluable. The timing of catheter removal was scheduled by calculating the time corresponding to the lowest levels, and thus activity, of all antithrombotic agents. Due to technical reasons, it was not possible to repeat PFA close to the trough levels of antiplatelets just before catheter removal, as planned. Thus, based on ROTEM results, and considering that the global hemostatic assessment was performed close to the peak enoxaparin, clopidogrel and aspirin levels, we proceeded to epidural catheter removal 24 hours after enoxaparin and 26 hours after the last aspirin/clopidogrel dose, a time-point close to the trough levels of both enoxaparin and antiplatelets. All antithrombotics were resumed early enough to minimize the thrombotic risk.

Apart from standard coagulation tests, we also measured anti-Xa activity; although therapeutic enoxaparin monitoring via anti-Xa is not typically necessary, in special situations such as critically ill patients, anti-Xa levels are often drawn to guide therapy. Additionally, we used the ROTEM and PFA to further assess the coagulation profile of the patient. ROTEM is a point-of-care assay that allows a global assessment of the clotting process but does not measure platelet function. For this purpose, we used PFA, a fast and accurate test that provides quantitative measurement of platelet function. Each test cartridge has a membrane with a 147 μm diameter aperture, coated with type-I Collagen and either Epinephrine (COL/EPI) or Adenosine 5'- Phosphate (COL/ADP). These stimulants cause platelet activation, and finally clot formation and occlusion of the aperture. The time required for full obstruction of blood flow through the aperture is reported as closure time.6 Clopidogrel results in both COL/EPI and COL/ADP closure time prolongation, while aspirin causes only COL/EPI prolongation with normal COL/ADP values.7

We consider that in analogous cases, useful tests include those employed in the present case, namely Full Blood Count, PT, aPTT, PFA and ROTEM. Ideally, they should be performed at times corresponding to both peak and trough levels of the antithrombotic agents. Multiple Platelet Function Analyzer is another assay that – similarly to PFA – can assess the effects of antiplatelet drugs on platelet aggregation and can be used alternatively. Also, TEG is a point-of-care hemostatic assay that measures the viscoelastic properties of whole blood and may be used as an alternative to ROTEM.

According to ASRA guidelines, the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel is not immediate if loading dose is omitted, and thus, neuraxial catheters may be left in place for 1–2 days.2 Unfortunately, there was no early multidisciplinary patient approach to determine the safest practice for epidural catheter handling. Hence, a possible time window for removal was missed and the catheter remained in-situ for several days, complicating things further. The above underlines the need for efficient interdisciplinary collaboration in the management of patients simultaneously treated by multiple different specialties. In the present case, the multidisciplinary care team, which was organized after several days, decided to remove the catheter since it was not in use while the infectious risk was increasing over time, especially after the 4th day.8 Additionally, there would be no benefit in postponing the removal since the patient's therapy was not expected to change in the near future. The decision was challenging because guidelines are clear only about individual antithrombotic agents, while evidence-based data on drug combinations are not available.9

The removal of an epidural catheter in a patient receiving multiple antithrombotic drugs is a challenging decision. The optimal time should correspond to the lowest level, thus the minimum efficacy of antithrombotic treatment. In cases similar to ours, an interval of at least 24–26 hours should elapse between the last dose of antithrombotics (aspirin/clopidogrel/therapeutic LMWH) and catheter removal. Ideally, the timing should be guided by tests and point-of-care coagulation and platelet function monitoring, performed at both peak and trough levels of the antithrombotic agents. The present report also highlights the importance of a case-specific management plan based on a multidisciplinary approach and close cooperation among the involved specialties.

Summary

Neuraxial hematoma is a rare complication of the epidural technique. In case of urgent multiple antithrombotic therapy, the optimal timing of epidural catheter removal may be quite challenging. We present the uneventful removal of an indwelling epidural catheter in a patient who was put on emergency triple antithrombotic treatment with heparin, aspirin and clopidogrel in the immediate postoperative period. Standard coagulation tests, along with Platelet Function Assay (PFA–200) and Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM) provided a helpful guidance in order to define the optimal conditions and timing for catheter removal, so as to reduce the risk of complications.

Funding This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mimata R., Higashi M., Yasui M., Hirai T., Yamaura K. Spinal epidural hematoma following epidural catheter removal in a patient with postoperative urgent coronary intervention and intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP): a case report. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:1356–1359. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.917716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horlocker T.T., Vandermeulen E., Kopp S.L., et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: american society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine evidence-based guidelines (Fourth Edition) Regional Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:263–309. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karan N., Bakshi S.G., Patil V., Sayed A. Use of thromboelastography for solving neuraxial blockade dilemma. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2019;47:355–356. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2019.05695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn E., Mehl J., Rosinia F.A., Liu H. Safe removal of an epidural catheter 72 hours after clopidogrel and aspirin administrations guided by platelet function analysis and thromboelastography. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:99–101. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.105813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergmann L., Kienbaum P., Görlinger K., Peters J. Uneventful removal of an epidural catheter guided by impedance aggregometry in a patient with recent coronary stenting and treated with clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:354–357. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kundu S.K., Heilmann E.J., Sio R., Garcia C., Davidson R.M., Ostgaard R.A. Description of an in vitro platelet function analyzer--PFA-100. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1995;21(Suppl 2):106–112. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1313612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mammen E.F., Comp P.C., Gosselin R., et al. PFA-100 system: a new method for assessment of platelet dysfunction. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1998;24:195–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bomberg H., Bayer I., Wagenpfeil S., et al. Prolonged Catheter Use and Infection in Regional Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:764–773. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf S.J., Kaisers U.X., Reske A.W., Struck M.F. Epidural catheter removal for initiation of emergency anticoagulant therapy in acute coronary syndrome–when is the time right? Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:582–584. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]