Abstract

This study prospectively compared the efficacy and safety between matched related donor-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (MRD-HSCT) (n = 108) and immunosuppressive therapy (IST) plus eltrombopag (EPAG) (IST + EPAG) (n = 104) to determine whether MRD-HSCT was still superior as a front-line treatment for patients with severe aplastic anemia (SAA). Compared with IST + EPAG group, patients in the MRD-HSCT achieved faster transfusion independence, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1.0 × 109/L (P < 0.05), as well as high percentage of normal blood routine at 6-month (86.5% vs. 23.7%, P < 0.001). In the MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups, 3-year overall survival (OS) was 84.2 ± 3.5% and 89.7 ± 3.1% (P = 0.164), whereas 3-year failure-free survival (FFS) was 81.4 ± 4.0% and 59.1 ± 4.9% (P = 0.002), respectively. Subgroup analysis indicated that the FFS of the MRD-HSCT was superior to that of the IST + EPAG among patients aged < 40 years old (81.0 ± 4.6% vs. 63.7 ± 6.5%, P = 0.033), and among patients with vSAA (86.1 ± 5.9% vs. 54.9 ± 7.9%, P = 0.003), while the 3-year OS of the IST + EPAG was higher than that of the MRD-HSCT among the patient aged ≥ 40 years old (100.0 ± 0.0% vs. 77.8 ± 9.8%, P = 0.036). Multivariate analysis showed that first-line MRD-HSCT treatment was associated favorably with normal blood results at 6-month and FFS (P < 0.05). These outcomes suggest that MRD-HSCT remains the preferred first-line option for SAA patients aged < 40 years old or with vSAA even in the era of EPAG.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13045-022-01324-1.

Keywords: Matched related transplantation, Immunosuppressive therapy, Eltrombopag, Severe aplastic anemia

To the editor

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) and immunosuppressive therapy (IST) are the two main treatment strategies for newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia (SAA) [1]. In spite of comparable overall survival (OS) between matched related donor-HSCT (MRD-HSCT) and IST, failure-free survival (FFS) has been reported to often be better in the former than the latter [2, 3], mainly because of a low rate of complete response (CR) and relatively high rate of relapse and clonal evolution after IST treatment [4]. In recent years, the addition of eltrombopag (EPAG), an oral synthetic small-molecule thrombopoietin receptor agonist, to standard IST has been shown to improve the speed and depth of a hematological response in patients with SAA, without additional toxic effects [5, 6]. Until recently, a study comparing MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG as first-line treatment suggested MRD-HSCT achieved a better OS in patients with very SAA (vSAA) and a higher FFS in all SAA patients. However, this study had some limitations, such as a small sample size and imbalanced characteristics, which may have reduced the reliability of the comparison outcome to some extent [7]. Therefore, it remains necessary to investigate whether the improvements associated with IST + EPAG were comparable to those of MRD-HSCT in SAA using a larger and well-designed study.

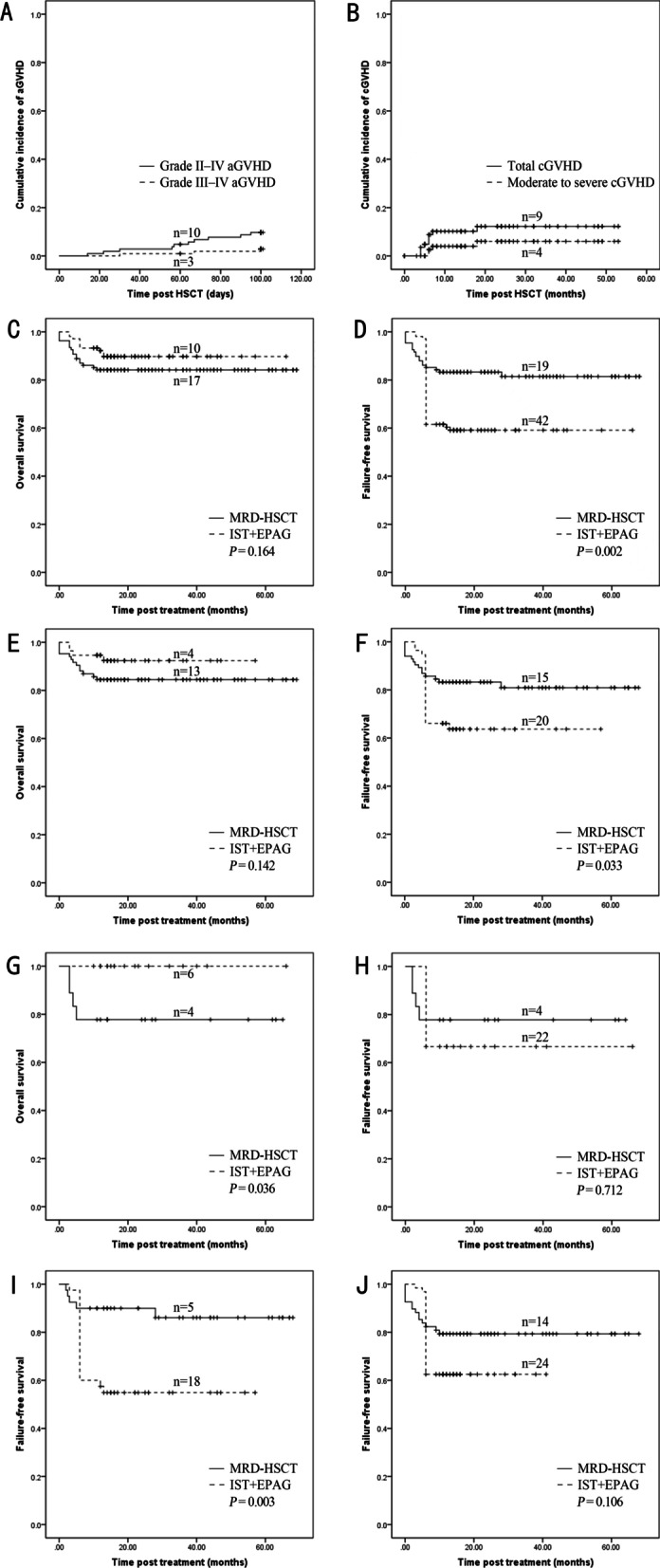

This multicenter prospective study compared the efficacy and safety of MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG as front-line therapy in contemporaneous SAA patients. Of the 216 patients enrolled in the study between January 2016 and February 2021, 108 received MRD-HSCT treatment, with the implementation process of the treatment being the same as that used in our previous study [8]. All the patients were analyzed. In the 108 patients who received IST + EPAG treatment, standard IST was administered as described in our previous study [9], while EPAG was initiated on day 1 at a dose of 50 mg per day and then increased by 25 mg every 2 weeks until a maximum of 150 mg or a dose resulting in a hematological response. Finally, only 104 patients administered EPAG for at least three months were eligible for analysis. Patients/methods and results are shown in Additional file 1. The characteristics of the patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1. The median age was lower in the MRD-HSCT group than that in the IST + EPAG group (P = 0.024). The median interval from diagnosis to treatment was longer in the MRD-HSCT group than that in the IST + EPAG group (P = 0.011) (Table 1). In the MRD-HSCT group, all the patients achieved myeloid engraftment, complete donor chimerism, engraftment time, and secondary GF (Table 1). In addition, the aGVHD/cGVHD incidence was acceptable (Fig. 1A, B), which was similar to the results of a previous study [10]. The adverse effects observed for EPAG included hyperbilirubinemia, liver enzyme elevation, and dyspepsia, all of which were ameliorated quickly by intensive supportive treatment, with the overall tolerability acceptable and consistent with the previously reported safety profile of EPAG [5, 11].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patient and donor (graft) and clinical outcomes between the two groups

| Variables | MRD-HSCT (n = 108) | IST + EPAG (n = 104) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, yr (range) | 29 (6–56) | 34.5 (4–69) | 0.024 |

| Age, no. (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 20 yr | 17 (15.7) | 24 (23.1) | |

| 20–40 yr | 67 (62.0) | 32 (30.8) | |

| ≥ 40 yr | 24 (22.2) | 48 (46.2) | |

| Sex, no. (%) | 0.767 | ||

| Male | 57 (52.8) | 57 (54.8) | |

| Female | 51 (47.2) | 47 (45.2) | |

| Disease status, no. (%) | 0.831 | ||

| SAA | 68 (66.7) | 64 (61.5) | |

| vSAA | 40 (33.3) | 40 (38.5) | |

| With PNH clone, no. (%) | 26 (24.1) | 19 (10.2) | 0.301 |

| ECOG score, median (range) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.537 |

| Median time from diagnosis to treatment, mth (range) | 3 (1.0–200) | 2 (0.5–240) | 0.011 |

| Median time to an ANC ≥ 1.0 × 109/L, d (range) | 15 (11–35) | 30 (4–58) | 0.002 |

| Median time to transfusion independence for RBCs, d (range) | 22 (13–32) | 63 (6–302) | < 0.001 |

| Median time to transfusion independence for platelets, d (range) | 12 (8–52) | 52 (11–287) | < 0.001 |

| Normal blood routine at 6-mth, no. (%) | 83 (86.5) | 23 (23.7) | < 0.001 |

| Early death, no (%) | 7 (6.5) | 2 (1.9) | 0.192 |

| Secondary clonal disease, no (%) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (2.9) | 0.587 |

| Relapsed, no (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | – |

| Alternative donor transplantation, no (%) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (9.6) | – |

| TRM, no (%) | 17 (15.7) | 10 (9.6) | 0.181 |

| Secondary GF, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | – | |

| aGVHD, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | – | |

| cGVHD, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | – | |

| TMA, no (% of TRM) | 2 (11.8) | – | |

| Poor graft function, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | – | |

| Infection, no (% of TRM) | 9 (52.8) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Heart failure, no (% of TRM) | – | 1 (10.0) | |

| Other, no (% of TRM) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Median follow-up time among living patients, mth (range) | 31.5 (13.0–69.0) | 30.5 (14.0–66.0) | 0.589 |

| Conditioning regimen | Flu + CY + ATG | rATG (pALG) + CsA + EPAG | |

| Donor median age, yr (range) | 30 (10–55) | – | |

| Donor sex, no. (%) | – | ||

| Male | 54 (50.0) | – | |

| Female | 54 (50.0) | – | |

| Blood types of donor to recipient, no. (%) | |||

| Matched | 65 (60.2) | – | |

| Major mismatched | 15 (13.9) | – | |

| Minor mismatched | 19 (17.6) | – | |

| Major and minor mismatched | 9 (8.3) | – | |

| Source of graft, no. (%) | |||

| BM | 4 (3.7) | – | |

| PB | 30 (27.8) | – | |

| BM + PB | 74 (68.5) | – | |

| Median MNC, × 108/kg (range) | 11.6 (3.2–24.4) | – | |

| Median CD34+ cells, × 106/kg (range) | 3.7 (1.1–8.6) | – | |

| Median time to ANC > 0.5 × 109/L, d (range) | 11 (7–21) | – | |

| Median time to PLT > 20.0 × 109/L, d (range) | 12 (8–52) | – | |

| Primary GF, no. (%) | 0 (0.0) | – | |

| Secondary GF, no. (%) | 2 (1.9) | – | |

| GF of platelet, no. (%) | 3 (2.9) | – | |

| Delayed platelet recovery, no. (%) | 4 (3.8) | – | |

| Poor graft function, no. (%) | 1 (0.9) | – | |

| Adverse events of attributed to EPAG, no. (%) | |||

| Skin (maculopapular and/or rash pruritus) | – | 3 (2.9) | |

| Abdominal pain | – | 2 (1.9) | |

| Joint pain | – | 2 (1.9) | |

| Liver test abnormality | |||

| Increased aminotransferase level | – | 42 (40.4) | |

| Increased blood bilirubin level | – | 19 (18.3) |

The bold values were statistically significant

MRD-HSCT matched related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, IST immunosuppressive therapy, EPAG eltrombopag, SAA severe aplastic anemia, vSAA very SAA, PNH paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Scale, BM bone marrow, PB peripheral blood, MNC mononuclear cell, ANC absolute neutrophil count, PLT platelet, GF graft failure, TRM treatment related mortality

Fig. 1.

GVHD after transplantation and survival after treatment with MRD-HSCT or IST + EPAG (including subgroups). A Grade II–IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) and Grade III–IV aGVHD after MRD-HSCT. B Total chronic GVHD (cGVHD) and moderate-to-severe cGVHD after MRD-HSCT. C OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups as a whole. D FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups as a whole. E OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with aged < 40 years. F FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients aged < 40 years. G OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age ≥ 40 years. H FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age ≥ 40 years. I FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with vSAA. J FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with SAA

At 6 months post-treatment, the time taken to achieve transfusion independence, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ l × 109/L, and subsequent normal blood results all favored the MRD-HSCT group compared with that observed in the IST + EPAG group (Table 1). Further details about the IST + EPAG response rate at 3 and 6 months are shown in Additional file 2. These results were similar to those of another study [7]. Multivariate analysis showed first-line MRD-HSCT was the only treatment associated with normal blood results six months after treatment (P < 0.001). Next, we performed a survival comparison between the MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups and each age subgroup. For the total population or patients aged < 40 years old, although there was no difference in OS between the MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups, a significant higher FFS rate was found in the former than that in the latter (Fig. 1C–F). For patients aged ≥ 40 years old after propensity score matching (the propensity score was calculated based on a multivariate logistic regression model, which took patient age, sex, and disease status between the two groups as covariates), there was a comparable FFS rate, with a higher OS rate in the IST + EPAG subgroup than in the MRD-HSCT subgroup (Fig. 1G, H). For patients aged < 20 and 20–39 years old, there were no significant differences in OS or FFS between the MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG groups (Additional file 3). Furthermore, FFS in the IST + EPAG group was still inferior to that of the MRD-HSCT group in patients with SAA. It is remarkable that FFS in the IST + EPAG group was significantly inferior to that of the MRD-HSCT group in patients with vSAA (Fig. 1I, J), which is consistent with the outcomes of a recent study [7].

In the current study, the FFS rate of approximately 60% in the IST + EPAG group was mainly due to the high none response rate of up to 30% at 6 months (Table 1), which was similar to that reported by another study [6]. Multivariate analysis showed that first-line MRD-HSCT and < 4 months between diagnosis and treatment were two favorable factors for FFS for the total population (P = 0.001 and P = 0.008, respectively, Additional file 4).

Notably, the survival outcomes in the IST + EPAG group may be due partly to patients who did not respond to initial therapy who subsequently received an allo-HSCT from alternative donors. Even so, our data still support that MRD-HSCT should be recommended in SAA patients as first-line treatment rather than IST + EPAG, especially for those younger than 40 years old or with vSAA, while transplants for patients older than 40 years carried a significant risk of mortality.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Patients/methods and results.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Response rates at 6-month in IST + EPAG whole group or subgroup.

Additional file 3: Fig. S1. Survival after treatment with MRD-HSCT or IST + EPAG for patients with further age stratification. (A) OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with aged < 20 years. (B) FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients age < 20 years. (C) OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age 20–39 years. (D) FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age 20–39 years.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with favorable outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (https://www.editsprings.cn/) for the expert linguistic services provided.

Abbreviations

- aGVHD

Acute graft-versus-host disease

- allo-HSCT

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- ANC

Absolute neutrophil count

- BM

Bone marrow

- BU

Busulfan

- cGVHD

Chronic graft-versus-host disease

- CsA

Cyclosporin A

- CY

Cyclophosphamide

- EPAG

Eltrombopag

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FFS

Failure-free survival

- Flu

Fludarabine

- GF

Graft failure

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IST

Immunosuppressive therapy

- MNCs

Mononuclear cells

- MTX

Methotrexate

- MRD

Matched related donor

- MMF

Mycophenolate mofetil

- OS

Overall survival

- PLT

Platelet

- PNH

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- PBSCs

Peripheral blood stem cells

- pALG

Pig antilymphocyte immunoglobulin

- rATG

Rabbit antithymocyte immunoglobulin

- SAA

Severe aplastic anemia

- TRM

Transplantation-related mortality

Author contributions

D-PW, L-SZ, and F-KZ designed the research scheme; L-ML, M-QL, and R-F analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, and all coauthors contributed the patients’ data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730003), National Science and Technology Major Project (2017ZX09304021), National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC0840604, 2017YFA0104502), Jiangsu Medical Outstanding Talents Project (JCRCA2016002), Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Center (YXZXA2016002).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by our institutional review boards, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Limin Liu, Meiqing Lei and Rong Fu have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Fengkui Zhang, Email: kfzhang@ihcams.ac.cn.

Liansheng Zhang, Email: zhanglsh@lzu.edu.cn.

Depei Wu, Email: wudepei@suda.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bacigalupo A. How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017;129:1428–1436. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-693481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida N, Kobayashi R, Yabe H, Kosaka Y, Yagasaki H, Watanabe K, et al. First-line treatment for severe aplastic anemia in children: bone marrow transplantation from a matched family donor versus immunosuppressive therapy. Haematologica. 2014;99:1784–1791. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.109355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y, Gao Q, Hu J, Liu X, Guan D, Zhang F. Allo-HSCT compared with immunosuppressive therapy for acquired aplastic anemia: a system review and meta-analysis. BMC Immunol. 2020;21:10. doi: 10.1186/s12865-020-0340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheinberg P, Wu CO, Nunez O, Young NS. Long-term outcome of pediatric patients with severe aplastic anemia treated with antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine. J Pediatr. 2008;153:814–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Townsley DM, Scheinberg P, Winkler T, Desmond R, Dumitriu B, Rios O, et al. Eltrombopag added to standard immunosuppression for aplastic anemia. New Eng J Med. 2017;376:1540–1550. doi: 10.1056/Nejmoa1613878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peffault de Latour R, Kulasekararaj A, Iacobelli S, Terwel SR, Cook R, Griffin M, et al. Eltrombopag added to immunosuppression in severe aplastic anemia. N Eng J Med. 2022;386:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang LF, Li L, Jia JS, Yang Y, Lin SY, Meng FK, et al. Frontline therapy options for adults with newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia: intensive immunosuppressive therapy plus eltrombopag or matched sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation? Transplant Cell Ther. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lei M, Li X, Zhang Y, Qu Q, Jiao W, Zhou H, et al. Comparable outcomes and health-related quality of life for severe aplastic anemia: haploidentical combined with a single cord blood unit versus matched related transplants. Front Oncol. 2022;11:714033. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.714033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Zhang Y, Jiao W, Zhou H, Wang Q, Jin S, et al. Comparison of efficacy and health-related quality of life of first-line haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with unrelated cord blood infusion and first-line immunosuppressive therapy for acquired severe aplastic anemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:3359–3369. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu LP, Jin S, Wang SQ, Xia LH, Bai H, Gao SJ, et al. Upfront haploidentical transplant for acquired severe aplastic anemia: registry-based comparison with matched related transplant. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:25. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olnes MJ, Scheinberg P, Calvo KR, Desmond R, Tang Y, Dumitriu B, et al. Eltrombopag and improved hematopoiesis in refractory aplastic anemia. N Eng J Med. 2012;367:11–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Patients/methods and results.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Response rates at 6-month in IST + EPAG whole group or subgroup.

Additional file 3: Fig. S1. Survival after treatment with MRD-HSCT or IST + EPAG for patients with further age stratification. (A) OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with aged < 20 years. (B) FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients age < 20 years. (C) OS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age 20–39 years. (D) FFS between MRD-HSCT and IST + EPAG subgroups for patients with age 20–39 years.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with favorable outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.