Abstract

Background and objective

Pain control is one of the major concerns after major hip surgeries. Suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block (S-FICB) is an alternative analgesic technique that can be considered as an effective and less invasive method than epidural analgesia (EA). In this retrospective study, we compared postoperative analgesic efficacy of single shot ultrasound guided S-FICB and EA after major hip surgery.

Methods

We retrospectively examined 150 patients who underwent major hip surgeries and who received S-FICB or EA. Seventy-two patients submitted to EA and 78 patients who received S-FICB were included and their medical records retrospectively reviewed. Morphine consumptions, VAS scores, and side effects were recorded. Patients under antiplatelet or anticoagulant theraphy were also registered. Morphine consumption and VAS scores were the primary endpoints, succes rate and complications were the secondary endpoints of our study. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Morphine consumption was lower at the emergence in the EA group but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups according to total opioid consumption (0 [0-0] vs 0 [0-0]; p = 0.52). There was no difference between VAS scores in the first 18 hours. Hypotension was significantly higher in the EA group (9 vs 21; p = 0.04).

Conclusion

In conclusion, S-FICB can provide comparable analgesia with EA in the early postoperative period after hip surgery but VAS scores were found lower in the EA group than S-FICB group after 18th hour. Hypotension has occured more frequently in patients receiving EA.

Keywords: Hip arthroplasty, Nerve blocks, Epidural analgesia

Introduction

Pain control is one of the major concerns after hip surgeries. Patients often experience moderate to severe pain after these procedures, and pain control has a significant impact on functional recovery after joint arthroplasty.1, 2 Effective pain control is reported to increase patient satisfaction.3 Poor pain control is associated with the prolonged rehabilitation time.3 Delayed recovery increases the risk of postoperative complications and postoperative pain emerges as a serious problem after the hip surgeries.3

Peripheral nerve blocks have been increasingly used in recent years to improve pain control and reduce complications.4, 5 Both single and continuous nerve blocks can be used as part of a multimodal analgesia protocol. Multimodal approaches include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, infiltration analgesia, and neuraxial techniques in combination with peripheral nerve blocks and are recommended for better pain control without the serious side effects of opioid and NSAIDs following surgery.4 Epidural analgesia (EA) is suitable for major hip surgeries but is subject to technical difficulties and has contraindications such as anticoagulation.6 This technique is also associated with many adverse effects.

Fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) is an alternative to neuraxial blocks and provides adequate unilateral analgesia with fewer adverse effects than EA.2 Hebbard et al. described and Desmet et al. modified a new approach, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block (S-FICB), which enables more effective cranial spread of the local anesthetics than conventional FICB.7, 8 FICB has been associated with reductions in both opiate consumption and pain scores in many studies, but a recent systematic review has reported that further research is needed to investigate the technique and administered volume for FICB.3 To date, there has been few studies reported focusing on the effectiveness of the S-FCIB after hip surgeries.3

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared the effectiveness of a single injection ultrasound-guided S-FICB with continuous lumbar EA in patients undergoing hip surgery. We hypothesized that the US-guided S-FICB would provide postoperative analgesia comparable to the EA. The primary outcomes were opioid consumption, static, and dynamic visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores. Secondary outcomes included success rate of two techniques and occurrence of side effects.

Methods

Study design

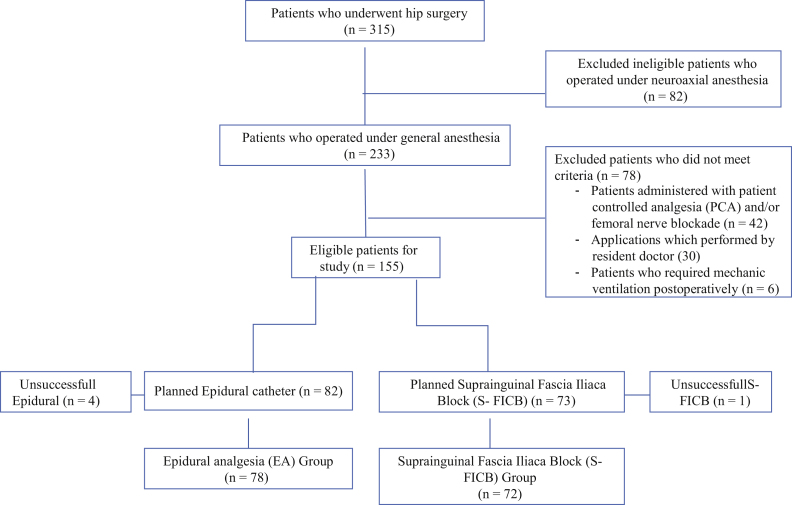

This retrospective cohort study included 150 patients and was approved by the local ethics committee (Mersin University Clinical Research Ethics Committee, No: 2018-81). Data were collected from the medical records of patients who underwent hip surgery between August 1, 2017 and January 30, 2018. Inclusion criteria were patients undergoing primary hip arthroplasty under general anesthesia either with EA (n = 78) or with S-FICB (n = 72) performed by the same anesthesiologist (MA) for the postoperative analgesia. Patients receiving spinal or combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, using chronic analgesic drugs, having neurological deficits in the lower extremities and illnesses that interfered with communication skills such as mechanical ventilation requirement and patients having insufficient data were excluded from the study. Patients with unsuccessful blocks were also excluded from the final evaluation. A flow chart demonstrating patient selection is presented in Figure 1. Although we have a standard protocol for postoperative analgesia, there was no standard preoperative analgesia protocol in our institution; meperidine or morphine treatment was used with acetaminophen intravenously in the hip fractured patients. Patients who were not treated according to this standard analgesia protocol (see below) were also excluded. Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia protocols for S-FICB and EA patients were as follows:

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the patient selection for the comparison between the two groups.

Anesthesia protocol

No premedication was applied to the patients before operation. All patients were monitored with electrocardiogram (ECG), invasive blood pressure (IBP), pulse oximetry (SaO2), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) in the operation room. General anesthesia was induced with propofol 0.5–2.0 mg.kg-1 or thiopental 3–5 mg.kg-1. Remifentanil 0.2–0.5 mcg.kg-1 and rocuronium 0.5–0.6 mg.kg-1 were administered to facilitate tracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with O2/N2O 50/50 fresh gas, and 0.5–2% sevoflurane. Neuromuscular blockade was antagonized with 0.05 mg.kg-1 neostigmine and 0,015 mg.kg-1 atropine before extubation.

Postoperative analgesia protocol for S-FICB and EA after hip surgeries

FICB and epidural catheter techniques which applied for postoperative analgesia were explained to the patients before surgery. The analgesic technique was preferred by the patients if there was no any contraindication. Epidural catheter was the first choice in suitable patients who were undecided about the analgesic method. S-FICB was the first choice for patients who could not inserted an epidural catheter due to the use of anticoagulants or technical difficulties. All patients received intravenous (IV) acetaminophen 20 mg.kg-1 during the operation. Morphine or meperidine was administered as needed during extubation and opioid doses were recorded. Our pain management team has visited patients at 6-h intervals. The target VAS-R score was ≤ 3. Static VAS (VAS-R) was evaluated during resting and dynamic VAS (VAS-M) was evaluated with active leg lifting to 15 degrees. The orthopedic ward nurse called our team if the patients complained of pain between scheduled visits.

EA: The epidural catheter was placed using the classical landmark technique during surgery after intubation and injection of 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine. Imaging techniques (fluoroscopy or US-guidance) were not used routinely. If VAS score was > 3, additional local anesthetic was administered and switched to infusion method (5–10 mL.h-1) after catheter location was verified. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was initiated if there was a problem with the catheter site and set to 0.5 mg morphine IV on demand with 15-minute lockout interval. Additional morphine or acetaminophen was administered as needed during the entire postoperative follow-up period. Patients were mobilized on the first postoperative day. If the patients complained of weakness, the epidural washout method with saline was used and the infusion rate was decreased.

S-FICB: Single-shot US guided S-FICB was administered after intubation and before surgery was initiated. An injection 0.40–0.60 mL.kg-1 of 0.25% bupivacaine was given using the US-guided longitudinal suprainguinal approach described by Desmet et al.8 Additional volume was administered if sufficient local anesthetic distribution was not observed. If VAS score was > 3 after extubation, it was considered a failed block. Acetaminophen was administered at 20 mg.kg-1 every 6 hours, except for patients without pain during the first postoperative 48 hours. In addition, if VAS score was > 3 at any time postoperatively, PCA was set to 0.5 mg morphine on demand with 15-minute lockout interval or equivalent dose of meperidine.

All patients were monitorized at least 30 minutes in the PACU after surgery. Therefore, first assessment was carried out and pain measurement, morphine consumption, and side effects at “zero hour” were also recorded in the PACU. Patients who had pain were given 0.5 mg intravenous morphine with the target VAS: Three in this period. Pain levels and morphin consumptions were evaluated by an anesthetist (SA) in the postoperative pain management team at the intensive care unit (ICU) and ward. Standard VAS (0–10 cm) was used for pain assessment. VAS scores were recorded while at rest (VAS-R) and during active movement (VAS-M) at postoperative 6th, 12th, 24th, and 48th hours. Daily morphine consumption at postoperative 6th, 12th, 24th, and 48th hours were also recorded. Meperidine was converted to morphine equivalent (7.5 mg IV meperidine = 1 mg IV morphine). Vital signs were tracked by using patient follow chart which recorded hourly by nurse in the ICU or ward. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90), hypoxia (SpO2 < 90%), and nausea-vomiting complaints which required any treatment were reported. Walking ability was evaluated to test quadriceps weakness on the second day, in patients with complaints associated with walking were evaluated with manual muscle test. Postoperative length of hospital stay and adverse events attributed to opioid use were compared. In addition, medical history of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drug use and the number of patients for whom the analgesic intervention failed were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated with using data for EA in a previous study and was found 67 patients per group needed to detect 30% change of morphine consumption between EA and S-FICB patients with a power of 80% and a risk of 0.05 for type 1 error.9 Shapiro-Wilk test was used for normality and comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test between the two groups because of non-normally distributed data. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare for categorical variables. Continous variables were expressed as median and interquartiles, categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Statistical analysis was performed with www.e-picos.com New York Software and Medcalc Statistical Package program. A p-value < 0.05 was determined statistically significant.

Results

We retrospectively analyzed data from a total of 150 patients. For comparison, the patients were divided into S-FICB group (n = 72) and EA group (n = 78) according to the postoperative analgesia they received. The patients’ demographic and surgical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to age, gender, comorbid dissease, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, wait time for surgery, transfused red blood cell, postoperative hemoglobin level or operative time (p > 0.05 for all) (Table 1). The use of acetaminophen was found higher in the S-FICB group than the EA (3.00 [2.00–3.00] vs 0.00 [0.00–0.25] respectively, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Patients demographics and operation characteristics.

| S-FICB (n = 72) | EA (n = 78) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.50 [65.00–77.75] | 69.00 [65.00–78.25] | 0.83 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 32 (44%) | 42 (53%) | |

| Female | 40 (56%) | 36 (47%) | 0.25 |

| Comorbid diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 31 (43.0%) | 31 (39.7%) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 26 (36.1%) | 22 (28.2%) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 16 (22.2%) | 12 (15.3%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (6.9%) | 4 (5.1%) | 0.71 |

| Renal failure | 6 (8.3%) | 5 (6.4%) | |

| Electrolyte imbalance | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| COPD | 2 (2.6%) | 5 (6.4%) | |

| Hypo/hyperthyroidism | 2 (2.6%) | 3 (3.8%) | |

| ASA | |||

| I | 1 (1.3%) | 6 (7.6%) | |

| II | 29 (40.2%) | 34 (43.5%) | 0.26 |

| III | 35 (48.6%) | 32 (41.0%) | |

| IV | 7 (9.7%) | 6 (7.6%) | |

| Preoperative analgesic treatment | |||

| No need any treatment | 31 (43%) | 40 (51.2%) | |

| Acetaminophen | 11 (15.2%) | 7 (8.9%) | |

| Meperidine infusion 10 mg.h-1 | 20 (27.7%) | 21 (26.9%) | 0.72 |

| Morphine infusion 1 mg.h-1 | 10 (13.8%) | 10 (12.8%) | |

| 1-year mortality | 8/72 (11.1%) | 11/78 (14.1%) | 0.63 |

| Waiting time for urgent surgery (days) | 0 0–1 | 0 0–1 | 0.38 |

| Surgery duration (h) | 120 [106–130] | 120 [110–135] | 0.58 |

| Length of stay (days) | 3 [3–4] | 3 [3–4] | 0.94 |

| Acetaminophen dose (vial) | 3.00 [2.00–3.00] | 0.00 [0.00–0.25] | 0.00 * |

| Used erythrocyte pack | 2 [2–3] | 2 [2–3] | 0.73 |

| Postoperative hematocrit level (mg.dL-1) | 9.50 [9.12–9.90] | 9.40 [9.20–9.60] | 0.36 |

| Surgery | |||

| Total hip replacement | 21 (29.2%) | 29 (37.2%) | |

| Partial hip replacement | 30 (41.6%) | 23 (29.5%) | 0.28 |

| Internal nail | 12 (16.7%) | 19 (24.3%) | |

| Plate-screw | 9 (12.5%) | 7 (9.0%) |

S-FICB, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block; EA, epidural analgesia; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Values were presented as median [Q1–Q3] or %.

Opioid consumption was lower at emergence in the EA group (0 [0–1] vs. 0 [0–0] mg respectively, p < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between two groups according to total opioid consumption (0 [0–0] vs. 0 [0–0] respectively, p > 0.05) (Table 2). Static and dynamic VAS scores were found similar in the first 18 hours, but VAS scores were significantly lower at 24th and 48th hours in the EA group (p < 0.05) (Table 3, Table 4).

Table 2.

Comparison of morphine consumption between the two groups.

| Group S-FICB |

Group EA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-max | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-max | p |

| 0th h | 0[0-1] | 0-2 | 0[0-0] | 0-3 | p < 0.05* |

| 6th h | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | 0 [0-0] | 0-6 | p > 0.05 |

| 12th h | 0 [0-0] | 0-4 | 0 [0-0] | 0-4 | p > 0.05 |

| 18th h | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | p > 0.05 |

| 24th h | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | p > 0.05 |

| 48th h | 0 [0-0] | 0-2 | 0 [0-0] | 0-3 | p > 0.05 |

| Total | 0 [0-0] | 0-12 | 0 [0-0] | 0-16 | p > 0.05 |

S-FICB, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block; EA, epidural analgesia.

Statistically significant value.

Table 3.

Comparison of Static VAS scores between the two groups.

| Group S-FICB |

Group EA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-max | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-max | p |

| 0th h | 1 [0-2] | 0-3 | 0 [0-2] | 0-4 | > 0.05 |

| 6th h | 1 [0-2] | 0-3 | 0 [0-2] | 0-4 | > 0.05 |

| 12th h | 1 [0-2] | 0-4 | 1 [0-2] | 0-3 | > 0.05 |

| 18th h | 1 [0-2] | 0-3 | 0 [0-2] | 0-3 | > 0.05 |

| 24th h | 0 [0-2] | 0-3 | 0 [0-1] | 0-3 | < 0.05* |

| 48th h | 0 [0-2] | 0-3 | 0 [0-0] | 0-2 | < 0.05* |

S-FICB, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block; EA, epidural analgesia.

Statistically significant value.

Table 4.

Comparison of Dynamic VAS scores between the two groups.

| Group S-FICB |

Group EA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-Max | Med [Q1-Q3] | Min-Max | p |

| 0th h | 3 [3-4] | 0-6 | 3 [3-4] | 0-6 | > 0.05 |

| 6th h | 3 [2-4] | 0-6 | 3 [2-4] | 0-6 | > 0.05 |

| 12th h | 3 [3-4] | 0-7 | 3 [2-4] | 0-5 | > 0.05 |

| 18th h | 3 [2-4] | 0-5 | 3 [2-4] | 0-5 | > 0.05 |

| 24th h | 3 [2-4] | 0-5 | 2 [2-3] | 0-5 | < 0.05* |

| 48th h | 3 [2-4] | 0-5 | 2 [0-3] | 0-4 | < 0.05* |

S-FICB, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block; EA, epidural analgesia.

Statistically significant value.

While US-guided S-FICB was successfully performed in 72 (98%) patients, the number of successful interventions was found 78 (95%) in the EA group. In terms of the number of patients treated without opioid, more patients have received opioid therapy (51 vs. 72 patients respectively, p < 0.01). The incidence of hypotension was significantly higher in the EA group (9 vs. 21 respectively, p < 0.05). The incidence of nausea-vomiting, hypoxia, and muscle weakness were found similar between two groups (Table 5). S-FICB was successfully performed without any complication in six patients who received antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs.

Table 5.

Comparison to success rate and side effects in the patient groups.

| S-FICB (n = 72) | EA (n = 78) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful block | 72/73 (98%) | 78/82 (95%) | 0.21 |

| Accidental catheter removal | N/A | 2 | – |

| No. of patients without morphine administered | 51/72 (70%) | 72/82 (92%) | < 0.01* |

| Nausea–vomiting | 6 (8%) | 11 (14%) | 0.25 |

| Hypotension | 9 | 21 | 0.04* |

| Hypoxia | 4 | 6 | 0.60 |

| Muscle weakness | 0 | 0 | 1 |

S-FICB, suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block; EA, epidural analgesia.

Statistically significant value.

Discussion

We observed from our study that US-guided S-FICB provided analgesia equal to the EA technique after hip surgeries in the early postoperative period, but that the EA provided significantly better analgesia after 18 hours. Morphine consumption was statistically equal at all measured time points except emergence, as was total morphine consumption. Hypotension was observed more frequent in patients receiving EA. S-FICB was successfully administered with no complications in patients under antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy.

A meta-analysis suggested that the analgesic efficacy of single-shot FICB lasts up to 24 hours.9 Temelkovska et al. reported that the analgesic effect of single-shot FICB begins to decrease after 12 hours.10 There are few studies comparing S-FICB with other analgesia methods in the literature. Our results indicated that single-shot S-FICB can provide adequate early postoperative analgesia after hip surgery. However, we found that it has limited duration of action compared to the EA technique, which can provide long-term pain control with infusion or repeated doses. Although morphine administered before extubation may have resulted in higher morphine consumption in the S-FICB group during emergence, total morphine consumption was similar between the two groups in our study. Regular acetaminophen reduces VAS pain score, opioid consumption, and opioid-related adverse effects.11 Average acetaminophen use was found to be higher in the S-FICB group than EA. The administration of acetaminophen may have contributed to the effectiveness of the analgesia in our S-FICB group.

Conventional FICB may offer better analgesia and reduce morphine consumption compared to a control group after hip surgeries.12 There are only two conflicting studies in the literature comparing conventional FICB and EA. Rashwan et al. found that patients in the EA group had lower pain score and tramadol consumption than patients who received continuous FICB after femur neck fracture surgery.13 However, Nooh et al. reported that both techniques had similar analgesic effect after hip and knee surgeries.14 Conventional FICB was administered using an unguided technique in both studies. Although FICB can be performed blind, US-guidance increases block success by ensuring injection in the correct space and allows monitoring for adequate distribution, resulting in better analgesia than the blind technique.15 In addition, the recommended volume is 30–40 mL for FICB, but 30 mL of local anesthetic was used in these studies. In the present study, the mean volume was 30.7 mL, but local anesthetic was administered with US-guidance and no patient received a volume less than 0.4 mL.kg-1. Furthermore, we performed FICB via proximal suprainguinal approach, which provides better analgesia than the conventional method.16

There is no gold standard anesthetic method for hip surgery. In terms of mortality, the advantage of neuroaxial techniques over general anesthesia has not been proven.17 If the patient prefers, neuroaxial anesthesia is the first choice in our clinic. However, general anesthesia is preferred in anticoagulant/antiplatelet drug use, serious heart valve diseases or operations that are known to last long. EA is the one of the best methods of pain management after hip arthroplasty. It is frequently implemented by catheter after these surgeries and optimal pain control is sustained even into the late postoperative period. It has been suggested that although EA provides better analgesia during movement than IV opioid administration, the lower pain score advantage of EA at rest is limited to the first 4–6 hours.18 The use of opioid added local anesthetics may provide better analgesia during neuraxial interventions but it may cause also more frequent side effects. EA may also have better analgesic effect than nerve blocks during exercise.19 However, peripheral nerve blocks may provide equal postoperative analgesia to the EA with fewer complications after lower extremity surgeries.18, 20 A study comparing the analgesic efficacy of these three methods showed that continuous 3-in-1 block could have a similar effect to EA and IV opioid administration with fewer side effects.21

US guidance is used when administering neuraxial or peripheral nerve blocks and increases rates of success. In the present study, the success rate for S-FICB was 98%. A review reported 99% success of epidural catheter placement using the landmark technique, but adequate anesthesia/analgesia may be achieved at a rate of only 76% at the lumbar epidural level.22 We determined a 93.8% success rate of EA in our study. However, factors such as misplacement or migration of the catheter and individual variations in the structure of the epidural area reduce the effectiveness of the EA in pain control.23 Accidental catheter removal is one of the problems associated with catheter techniques. This occurred in two patients in the EA group in our study. While fewer patients needed opioid treatment in the EA group, the mean VAS scores and total morphine consumption were similar in the two groups. This suggests that patients whose catheters were misplaced or accidentally removed may have increased the overall morphine consumption of the EA group in our study.

Although it provides better pain control than many other techniques, continuous EA causes certain adverse effects such as urinary retention, hypotension, and bilateral muscle weakness.2, 18 Hypotension is a common side effect of EA due to vascular dilation caused by sympathetic denervation. Hypotension occurs more frequently with the epidural technique than systemic analgesia and nerve blocks. Consistent with the literature, in our study hypotension was significantly more common in the EA group than the S-FICB group. All other adverse effects occurred at the same frequency in both groups.

Muscle weakness is attributed to both FICB and the EA. Behrends et al. suggested that preoperative FICB did not improve pain control after hip arthroscopy but may cause quadriceps weakness.24 However, the results of a meta-analysis are inconsistent with this finding.3 It was suggested that the programmed intermittent epidural bolus technique may provide greater dermatomal spread and lower pain scores compared to continuous administration.25 Moreover, adding continuous infusion to epidural PCA may increase analgesic quality but also increase the incidence of muscle weakness.26 Recent studies showed that a programmed intermittent bolus regimen provides better pain control and less motor blockade than continuous infusion via both EA and lumbar plexus catheter.25 But, this undesirable event could be ceased by repositioning the catheter or reducing anesthetic concentration by suspending infusion and using washout technique.27, 28 The intermittent bolus method was used in our patients according to our analgesia protocol and no patient suffered muscle weakness in either group on the first postoperative day.

There is no consensus regarding the timing of surgery for hip fracture patients who are being treated with anticoagulant drugs. In orthopedic surgery guidelines, the moderate recommendation is that fracture patients undergo surgery within the first 48 hours to reduce mortality.29 However, the epidural technique is not suitable for patients using anticoagulant therapy without delay. Neuraxial block is contraindicated in patients receiving antiplatelet or anticoagulant, whereas peripheral nerve block may be administered in compressible regions.6 The injection site for S-FICB is distant from major nerves and blood vessels; therefore, US-guided S-FICB can be considered safe in this patient group. Almeida et al. showed that FICB under sedation was sufficient for surgery in hip fracture patients receiving anticoagulant drugs.30 We believe that US-guided S-FICB may be used in patients using antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs and could offer a substantial advantage for both anesthesia and analgesia for hip fracture surgery. These patients should be monitored more closely due to the development of hematoma in addition to the described complications.

We conducted a retrospective study, and it was major limitation of our study. Data was collected from well-structured follow-up records kept by the postoperative pain management team. Nevertheless, we could report only clinically observed side effects. Secondly, urinary retention could not be evaluated because urinary catheter was inserted as standard during the follow-up period. Additionally, there was no standard preoperative analgesia management for hip fracture patients. Finally, VAS scores and opioid consumption amounts were recorded only once during the emergence period.

Conclusion

In conclusion, single-shot S-FICB may provide similar postoperative pain control as compared to EA in the first 18 hours after hip surgery. However, VAS scores were lower in the EA group than S-FICB group after the 18th hour. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups according to total opioid consumption in the first 48 hours. Hypotension has occured more frequently in patients receiving EA but other side effects were similar between two groups.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Duellman T.J., Gaffigan C., Milbrandt J.C., et al. Multi-modal, pre-emptive analgesia decreases the length of hospital stay following total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2009;32:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singelyn F.J., Ferrant T., Malisse M.F., et al. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous femoral nerve sheath block on rehabilitation after unilateral total-hip arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao Y., Tan H., Sun R., et al. Fascia iliaca compartment block reduces pain and opioid consumption after total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJS. 2019;65:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi G., Gandhi K., Shah N., et al. Peripheral nerve blocks in the management of postoperative pain: challenges and opportunities. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chelly J.E., Ghisi D., Fanelli A. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in acute pain management. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(Suppl 1):i86–96. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horlocker T.T., Vandermeuelen E., Kopp S.L., et al. Regional Anesthesia in the Patient Receiving Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic Therapy American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Fourth Edition) Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:263–309. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hebbard P., Ivanusic J., Sha S. Ultrasound-guided supra-inguinal fascia iliaca block: a cadaveric evaluation of a novel approach. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desmet M., Vermeylen K., Van Herreweghe I., et al. A Longitudinal Supra-Inguinal Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block Reduces Morphine Consumption After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:327–333. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milligan K.R., Convery P.N., Weir P., et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Epidural Infusions of Levobupivacaine With and Without Clonidine for Postoperative Pain Relief in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Replacement. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:393–397. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200008000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevanovska M.T., Durnev V., Srceva M.J., et al. Continuous femoral nerve block versus fascia iliaca compartment block as postoperative analgesia in patients with hip fracture. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2014;35:85–93. doi: 10.2478/prilozi-2014-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda Y., Fukunishi S., Nishio S., et al. Evaluating the Effect of Intravenous Acetaminophen in Multimodal Analgesia After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenberg J., Møller A.M. Systematic review of the effects of fascia iliaca compartment block on hip fracture patients before operation. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:1368–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashwan D. Levobupivacaine patient controlled analgesia: Epidural versus blind fascia iliaca compartment analgesia – A comparative study. EgJA. 2013;29:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nooh N.G.E., Hamed A.M.S., Moharam A.A., et al. A comparative study on combined general anesthesia with either continuous fascia iliaca block or epidural anesthesia in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol. 2016;9:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalens B., Vanneuville G., Tanguy A. Comparison of the fascia iliaca compartment block with the 3-in-1 block in children. Anesth Analg. 1989;69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar K., Pandey R.K., Bhalla A.P., et al. Comparison of conventional infrainguinal versus modified proximal suprainguinal approach of Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block for postoperative analgesia in Total Hip Arthroplasty. A prospective randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2015;66:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell C.M., McLoughlin L., Patterson C.C., et al. Perioperative outcomes in the context of mode of anaesthesia for patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi P., Bhandari M., Scott J., et al. Epidural analgesia for pain relief following hip or knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies A.F., Segar E.P., Murdoch J., et al. Epidural infusion or combined femoral and sciatic nerve blocks as perioperative analgesia for knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:368–374. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fowler S.J., Symons J., Sabato S., et al. Epidural analgesia compared with peripheral nerve blockade after major knee surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:154–164. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tetsunaga T., Sato T., Shiota N., et al. Comparison of Continuous Epidural Analgesia, Patient-Controlled Analgesia with Morphine, and Continuous Three-in-One Femoral Nerve Block on Postoperative Outcomes after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7:164–170. doi: 10.4055/cios.2015.7.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ready L.B. Acute pain: lessons learned from 25,000 patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(99)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermanides J., Hollmann M.W., Stevens M.F., et al. Failed epidural: causes and management. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:144–154. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behrends M., Yap E.N., Zhang A.L., et al. Preoperative Fascia Iliaca Block Does Not Improve Analgesia after Arthroscopic Hip Surgery, but Causes Quadriceps Muscles Weakness: A Randomized, Double-blind Trial. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:536–543. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heesen M., Bohmer J., Klohr S., et al. The effect of adding a background infusion to patient-controlled epidural labor analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:149–158. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullingham A., Liang S., Edmonds E., et al. Continuous epidural infusion vs programmed intermittent epidural bolus for labour analgesia: a prospective, controlled, before-and-after cohort study of labour outcomes. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappelleri G., Ferrua P., Berruto M. The Impact of Anesthesia and Surgical Exposure on Quadriceps Muscle Function. Orthop Muscul Syst. 2014;3:147. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed A., Baig T. Incidence of lower limb motor weakness in patients receiving postoperative epidural analgesia and factors associated with it: An observational study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10:149–153. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.168806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts K.C., Brox W.T., Jevsevar D.S., et al. Management of Hip Fractures in the elderly. JAAOS. 2015;23:131–137. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almeida C.R., Francisco E.M., Pinho-Oliveira V., et al. Fascia iliaca block associated only with deep sedation in high-risk patients, taking P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, for intramedullary femoral fixation in intertrochanteric hip fracture: a series of 3 cases. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]