Abstract

Background

Anxiety is a state of worry caused by the anticipation of external or internal danger. Awareness During Anesthesia (ADA) is an unexpected memory recall during anesthesia. In this study, we aimed to determine the factors that affect preoperative anxiety and observe the incidence of ADA, as well as to determine the anxiety levels of these patients with a history of ADA.

Methods

This study was planned to be prospective, observational, and cross-sectional. Patients in whom septoplasty was planned, who was admitted to the anesthesiology outpatients between March 2018 and September 2018, were ASA I−II, and aged 18−70 years were included in the study. The demographic characteristics of patients were recorded. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to determine anxiety during a preoperative evaluation. The modified Brice awareness score was used simultaneously to determine previous ADA.

Results

The anxiety scores of patients who were conscious during anesthesia were higher than other patients. The mean STAI score was 40.85 ± 14.8 in the 799 patients who met the inclusion criteria of this study. When the anxiety scores were compared, the scores were higher in females than in males (p < 0.05). The mean STAI score was found as 40.3 ± 13.8 in patients who dreamed during anesthesia.

Conclusion

It is important to determine the anxiety levels of patients in the preoperative period to prevent the associated complications. Preoperative anxiety, besides preventing ADA, should be dealt with in a multidisciplinary manner. ADA should be carefully questioned while evaluating previous anesthesia experiences.

Keywords: Preoperative anxiety, Awareness during anesthesia, State-trait anxiety inventory

Resumo

Justificativa

A ansiedade é um estado de preocupação causado pela expectativa de perigo externo ou interno. Consciência durante a anestesia (CDA) é a evocação imprevista da memória de eventos intra-anestésicos. O objetivo deste estudo foi determinar os fatores que afetam a ansiedade pré-operatória, a incidência de CDA e os níveis de ansiedade nos pacientes com antecedente de CDA.

Método

O estudo foi planificado como prospectivo, observacional e transversal. Foram incluídos no estudo pacientes programados para septoplastia eletiva, admitidos ao ambulatório de anestesiologia entre Março de 2018 e Setembro de 2018, com classe funcional ASA I−II e faixa etária entre 18 e 70 anos. As características demográficas dos pacientes foram registradas. O Inventário de Ansiedade Traço-Estado (IDATE) foi utilizado para determinar a ansiedade durante a avaliação pré-operatória. Simultaneamente, o escore de consciência de Brice modificado foi usado para determinar CDA anterior.

Resultados

Os escores de ansiedade dos pacientes que apresentaram CDA foram mais elevados do que de outros pacientes. A pontuação média do IDATE foi 40,85 ± 14,8 nos 799 pacientes que obedeceram aos critérios de inclusão do estudo. Quando os escores de ansiedade foram comparados, os escores foram maiores no sexo feminino do que no masculino (p < 0,05). O escore médio do IDATE encontrado foi 40,3 ± 13,8 nos pacientes que relataram sonhos durante a anestesia.

Conclusão

É importante determinar no pré-operatório os níveis de ansiedade dos pacientes para evitar as complicações associadas. Ansiedade pré-operatória e a prevenção de CDA devem ser tratadas com abordagem multiprofissional. A CDA deve ser cuidadosamente investigada, avaliando-se as experiências vividas pelo paciente em anestesias pregressas.

Palavras-chaves: Ansiedade pré-operatória, Consciência durante a anestesia, Inventário de ansiedade traço-estado

Introduction

Anxiety is a state of worry caused by the anticipation of external or internal danger. In studies, it has been shown that 45.3% of hospitalized patients and 38.3% of outpatients have significant preoperative anxiety. Anxiety and fear are seen with different severities in many patients during the preoperative period. Anxiety has been reported in 60−80% of adult patients and in 50−70% of pediatric patients who will undergo surgery.1, 2 In addition, the same patient groups experience anxiety about remembering the surgery. Anxiety creates some serious problems before surgery. It exacerbates pain perception. The extent of instant anxiety increases the reported pain severity and decreases the tolerance to pain. This result is accompanied by additional analgesic requirements and prolonged discharge times in patients. Anxiety may depend on the type of anesthesia, the patient's previous experience, the way the patient comes to the hospital, sex, personality structure, the type of surgery, and the fear of experiencing pain after surgery.3 It has been shown that better communication between anesthesiologists and patients significantly reduces preoperative anxiety.1

Awareness During Anesthesia (ADA) is unexpected memory recall during anesthesia. During general anesthesia, the recall of intraoperative events has been defined to occur in four stages: conscious perception or recall, conscious perception without conscious recall, unconscious perception and unconscious recall, and no perception and no unconscious recall. Some patients remember sounds and dreams during surgery, whereas some experience pain and intense stress. The causes and risk factors of ADA and prevention methods have been defined in the literature.4 The risk factors described in the literature are as follows: high American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, undergoing surgery in a major operation group, and undergoing emergency surgery.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the factors that affect preoperative anxiety, and a secondary aim was to observe the incidence of a history of ADA during the observational period as well as to determine the anxiety levels of these patients with a history of ADA.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital (Reference: 42/31) and was then registered (Clinical Trials: NCT03389581). This study was planned to be prospective, observational, and cross-sectional. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients in whom septoplasty was planned by an otolaryngologist, patients who were admitted to the anesthesiology outpatient clinic between March 2018 and September 2018, patients with ASA scores of I−II and patients aged 18−70 years were included in the study. Patients from whom informed consent was not obtained, patients who had not been under general anesthesia before (to detect ADA history), patients with ASA scores III−IV, patients who were illiterate, patients who had a psychiatric disease such as high anxiety (Second Type of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI] > 45) and patients who were using psychiatric drugs were excluded from the study. The demographic characteristics of the patients (age, sex, body surface area, educational status, and previous surgery type), STAI levels, and patient characteristics, including the presence of ADA and dreaming, were recorded.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which is widely used and has been accepted as the gold standard, was used to determine anxiety. If the patients’ second type of STAI levels were higher than 45, these patients were excluded from the study. The first type of STAI (Table 1) was taken by the study group. In our study, the modified Brice awareness score, which has been used by similar studies designed to assess past intraoperative awareness simultaneously, was used to determine previous ADA (Table 2).5, 6, 7 All questionnaires were taken one day before surgery in the outpatient clinic of anesthesiology.

Table 1.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form.

| Number | Feelings | Not at all | Somewhat | Moderately so | Very much so |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel calm | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 2 | I feel secure | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 3 | I am tense | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 4 | I feel strained | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 5 | I feel at ease | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 6 | I feel upset | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 7 | I am presently worrying over possible misfortunes | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 8 | I feel satisfied | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 9 | I feel frightened | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 10 | I feel comfortable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 11 | I feel self-confident | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 12 | I feel nervous | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 13 | I am jittery | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 14 | I feel indecisive | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 15 | I am relaxed | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 16 | I feel content | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 17 | I am worried | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 18 | I feel confused | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 19 | I feel steady | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| 20 | I feel pleasant | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

Table 2.

Modified Brice questionnaire.

| 1. What was the last thing you remember before surgery? |

| 2. What is the first thing you remember once you woke up? |

| 3. Did you have any dreams while you were asleep for surgery? |

| 4. Were you put to sleep gently? |

| 5. Did you have any problems going to sleep? |

The validity and reliability of the scale were established by Öner in Turkey.8 High scores indicate high anxiety levels, and low scores indicate low anxiety levels. The scale contains four scores ranging from “never” to “completely”. There are two types of statements in the STAI. Direct statements express negative emotions, and reverse statements express positive emotions. The reverse statements in the STAI were as follows: 1, 2, 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 19 and 20. Direct and reverse expressions have separate values. The total score of the reverse expressions is subtracted from the total score of the direct expressions. An unchanging number that had already been determined was added to the results. This constant value for the STAI was 50. The resulting value indicates an individual's anxiety rating. The STAI is a very sensitive tool for evaluating emotional responses with sudden changes. Scores range between 20 and 80. The threshold value for the classification of anxiety is 45. STAI scores ≤ 45 are accepted to indicate low anxiety, and STAI scores > 45 are accepted to indicate high anxiety.3

All patients with a history of ADA were informed in detail about the anesthesia procedure to be applied during the perioperative period by talking face to face before the operation in the anesthesiology outpatient clinic. Preoperative anxiety and fear may lead to an increase in the levels of stress hormones, resulting in undesirable metabolic responses before anesthesia, including high systemic catecholamine levels that result in increased arterial blood pressure and heart rate. Because of this, all patients with high anxiety scores were directed to the psychiatrist to prevent complications due to high anxiety after providing information to the operation team (anesthesiologist, surgeon, anesthesia technician, operating room nurse, and operating room technician) before the operation. A history of ADA increases the probability of experiencing recurrence. The probability of recurrence is accepted as 1.6%.9 In this subject, the aim was to prevent the recurrence of ADA and to take necessary measures (proper premedication, checking all devices in the anesthetic procedure, monitoring, etc.) to prevent any undesired complications.

Statistical analysis

The incidence of ADA ranges from 0.2−0.9%.7 A sample size of 765 would allow us to detect an incidence of 0.5% (with a margin of error of 0.5%) with a 95% Confidence Interval. To account for protocol deviations and patients being lost to follow-up, we planned to include 1200 patients. The sample size was calculated using the ciss.wald function of the binomSamSize library in the R programming language. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 22.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analysis. Numerical values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and median (min−max). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check normality. Student's t test was used for continuous variables with a normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables without a normal distribution. Chi-Square tests were used for categorical variables, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

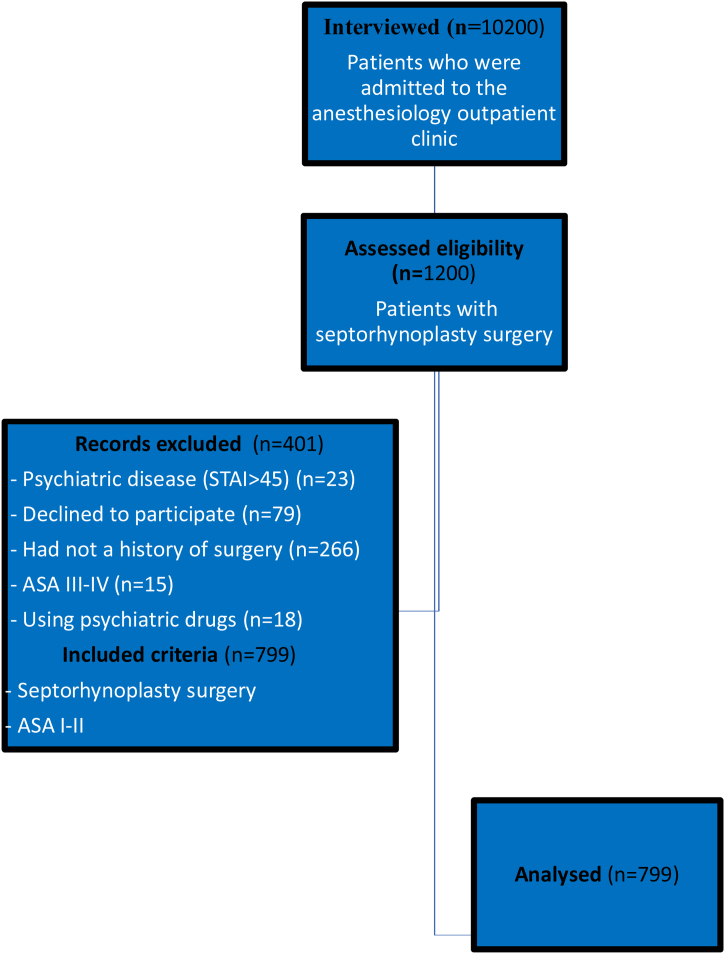

Septorhinoplasty was planned in 1200 of 10,200 patients who were admitted to the anesthesiology outpatient clinic during the study period (Fig. 1). The mean STAI score was 40.85 ± 14.8 in the 799 patients who met the inclusion criteria of this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study.

Three hundred sixty-two patients (45.3%) were female, and 437 (54.7%) were male. When the anxiety scores were compared, the scores were higher in females than in males (p < 0.05). In addition, 149 females and 137 males had high anxiety (Table 3). According to the patient's past operation history, 65 (24.2%) of 194 patients who underwent emergency surgery and 221 (75.2%) of 605 patients who underwent elective surgery had high anxiety scores; no difference was found between them (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic data and relationship with STAI score.

| STAI score (mean ± SD, median [min−max]) | High/Low anxiety (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female (n = 362) | 39.4 ± 15.33 | 149/213 |

| 36 (20−80) | ||

| Male (n = 437) | 42.61 ± 13.97 | 137/300 |

| 42 (20−80) | ||

| p-value | < 0.001a | 0.004c |

| Age | ||

| < 30 (n = 248) | 39.42 ± 16.51 | 66/182 |

| 36 (20−80) | ||

| 31-50 (n = 371) | 41.89 ± 14.06 | 151/220 |

| 40 (21−80) | ||

| > 51 (n = 180) | 40.69 ± 13.67 | 69/111 |

| 38 (20−70) | ||

| p-value | 0.124b | < 0.001c |

| Operation type | ||

| Emergency (n = 194) | 42.03 ± 16.78 | 65/129 |

| 37 (20−80) | ||

| Elective (n = 605) | 40.48 ± 14.11 | 221/384 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| p-value | 0.722a | 0.445c |

| ASA score | ||

| I (n = 458) | 40.88 ± 15.12 | 158/300 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| II (n = 341) | 40.82 ± 14.39 | 128/213 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| p-value | 0.726a | 0.375c |

| Educational status | ||

| Primary school (n = 187) | 41.19 ± 14.91 | 67/120 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| Middle school (n = 279) | 39.96 ± 14.84 | 94/185 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| High school (n = 192) | 41.6 ± 14.91 | 72/120 |

| 39 (20−80) | ||

| University (n = 141) | 41.14 ± 14.53 | 53/88 |

| 38 (20−80) | ||

| p-value | 0.551b | 0.807c |

The STAI values were given as mean ± standart deviation and median (min−max); p < 00.5 significant; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

Mann-Whitey U test.

Kruskal Wallis test.

Pearson’s Chi-Square test.

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of ASA scores (Table 3). According to educational status, there were 187 (23.4%) primary school graduates, 279 (34.9%) secondary school graduates, 192 (24.03%) high school graduates, and 141 (17.64%) university graduates (Table 3).

All patients were compared in three groups according to age.10 The STAI score of the 248 patients under the age of 30 years was 39.42 ± 16.51 (mean ± SD). The STAI score of the 371 patients whose ages ranged from 30−50 years was 41.89 ± 14.06. The STAI score of the 180 patients aged over 50 years was 40.69 ± 13.67 (Table 3). In addition, 66 (26.6%) patients < 30 years of age, 151 (40.7%) patients 30−50 years of age, and 69 (38.3%) patients aged over 50 years had high anxiety scores. Although there was no difference in terms of STAI values among all three age groups, fewer patients aged < 30 years had high anxiety scores (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

During the study, ADA was observed in 8 patients in the entire patient group who were admitted to the outpatient clinic of anesthesiology. Five of them suffered from a previous ADA experience and reported this spontaneously while being questioned regarding the previous history of anesthesia as a part of the preanesthetic evaluation. Three of them were in the study group who fulfilled the study criteria and experienced ADA according to modified Brice questionnaires. The mean STAI value of the three patients who experienced ADA was 68 ± 3.46 (Table 4). This value was higher in patients with ADA than in patients without ADA. One of the 3 patients who experienced ADA underwent open heart surgery (aortic valve replacement), one underwent a Cesarean Section (C/S), and the other underwent emergency surgery after a traffic accident.

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with awareness.

| Number | Gender | Age | ASA | Operation type | Type of surgery | Educational status | STAI score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 43 | II | Emergency | ObsGyn | Primary school | 70 |

| 2 | F | 51 | II | Elective | CVS | University | 70 |

| 3 | M | 24 | I | Emergency | ORT | High school | 64 |

ObsGyn, Obstetrics and Gynecology; CVS, Cardiovascular Surgery; ORT, Orthopedics; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

Patients who dreamed during anesthesia were evaluated, and their characteristics provided given in Table 5. The mean STAI score was 40.3 ± 13.8 in patients who dreamed during anesthesia. There was no difference between dreamers during general anesthesia and nondreamers and all patients in terms of this score.

Table 5.

Characteristics of dreaming patients.

| Number | Gender | Age | ASA | Operation type | Type of surgery | Educational status | STAI score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 44 | I | Elective | GS | Primary school | 34 |

| 2 | M | 24 | I | Elective | ENT | Middle school | 43 |

| 3 | M | 25 | I | Emergency | GS | High school | 37 |

| 4 | F | 56 | II | Elective | ORT | University | 64 |

| 5 | M | 24 | I | Elective | GS | High school | 26 |

| 6 | F | 61 | I | Elective | URO | University | 49 |

| 7 | F | 34 | II | Elective | GS | Primary school | 23 |

| 8 | F | 37 | I | Elective | GS | High school | 51 |

| 9 | F | 48 | II | Elective | CVS | University | 24 |

| 10 | M | 34 | I | Elective | ENT | Primary school | 52 |

F, Female; M, Male; GS, General Surgery; CVS, Cardiovascular Surgery; ENT, Ear Nose Throat surgery; URO, Urology Surgery; ORT, Orthopedics; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Of the patients included in the study, 293 (36.7%) had previously undergone general surgery, 76 (9.5%) had brain surgery, 21 (2.6%) had cardiovascular surgery, 157 (19.6%) had ear-nose-throat surgery, 102 (12.8%) had orthopedic surgery, 61 (7.6%) had plastic surgery, 74 (9.3%) had urologic surgery, 7 (0.9%) had female obstetric surgery, and 8 (1%) had ocular surgery. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of the type of previous surgery (Table 6).

Table 6.

The relationship between the type of surgery and the STAI score.

| STAI score, mean ± SD (median min−max) | High anxiety/Low anxiety (n) | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgery | 42.12 ± 16.13 | 111/182 | < 0.001a |

| 37 (20−80) | |||

| Neurosurgery | 38.72 ± 13.91 | 25/51 | < 0.001a |

| 36 (20−70) | |||

| Cardiovascular surgery | 40.19 ± 14.26 | 9/12 | 0.513a |

| 30 (21−66) | |||

| Ear-nose-throat surgery | 38.22 ± 14.92 | 42/115 | < 0.001a |

| 36 (20−80) | |||

| Orthopedy | 42.51 ± 14.34 | 42/60 | 0.075a |

| 41 (20−74) | |||

| Plastic and reconstructive surgery | 41.2 ± 13.62 | 22/39 | 0.030a |

| 38 (21−72) | |||

| Urology surgery | 41.55 ± 11.71 | 28/46 | 0.036a |

| 39 (26−76) | |||

| Ophthalmology | 33.13 ± 9.36 | 1/7 | 0.034a |

| 27 (27−52) | |||

| Obstetrics and ginecology | 46.86 ± 7.45 | 6/1 | 0.059a |

| 50 (30−50) |

Chi-Square godness of fit test for number of high/low anxiety patients; the STAI values were given as mean ± standart deviation and median (min−max); STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Discussion

In this study, although the factors affecting preoperative anxiety were revealed during a preoperative evaluation, it was found that the anxiety scores of patients who were conscious during anesthesia were higher than those of other patients.

Studies have revealed a relationship between surgery type and preoperative anxiety. It has been found that anxiety scores are higher with surgical interventions that may result in loss of organs or that are related to malignancy.11 In terms of operation size, small surgeries do not affect anxiety levels, and moderate and large surgeries are associated with high anxiety levels. In this study, all admitted were selected from patients undergoing septoplasty who were considered to have low anxiety in order to eliminate this difference due to the type of surgery.

Many studies have shown a relationship between sex and anxiety; STAI scores have been found to be higher in females than in males.12 Similarly, we found that anxiety levels were higher in females (42.61 ± 13.97) than in males (39.4 ± 15.33). We believe that this result is due to the following: epidemiologically, there is a tendency for depression and anxiety disorders to be seen more frequently in females than in males. Females readily express their anxiety, and males hide their feelings due to social pressure. It has been emphasized that ADA is more prevalent in females than in males, which is due to the faster recovery of females.13 In our study, two of the three patients who experienced ADA were females. Anxiety scores were found to be higher in both the female patients of the group and those who experienced ADA.

There are studies that have shown a relationship among anxiety, age, and awareness. In one study, it was emphasized that ADA was more frequent in patients aged less than 60 years.6 In this study, three patients who experienced ADA were aged less than 60 years, similar to the literature. In addition, different anxiety levels were found in different age groups in many studies. Grabow et al.14 found higher preoperative anxiety levels in young people. In a study conducted in our society, it was observed that elderly patients had a more fatalistic perspective. Young patients are more likely to be aware of the events that occur in healthcare through greater use of mass media tools, which increases their anxiety levels.15 Although we found no differences in mean STAI values in all three groups, a few patients aged less than 30 years had high anxiety scores. This is because aesthetic concerns in our group of patients aged less than 30 years were greater than anesthesia- and surgery-related concerns.

The presence of previous pain experience affects both the level of fear experienced and anxiety. In our study, when questioned about the previous history of surgery, no patients reported concerns about postoperative pain. We believe this situation is caused by the experience of pain caused by social and individual differences.

Studies have shown that anxiety levels due to anesthesia experience are related to sex, anxiety levels are lower in males than in females, and higher anxiety scores are found in patients who undergo anesthesia.12 In addition, two studies reported that anesthetic history did not change the anxiety level.15, 16 In this study, we found lower anxiety levels in males compared with the literature. We found low anxiety levels in males because, to test ADA, patients without a history of anesthesia were excluded, so no relationship with anxiety could be established.

In the literature, the ASA score has been found to be effective on preoperative anxiety.11, 15 Low ASA scores are associated with low anxiety, and high scores are associated with high anxiety. No such difference was found in our study. We believe that this result may be due to the low-risk ASA I−II group, as well as the absence of adequate information by the surgeon about the current diseases and risks of the operations in the preoperative period before the anesthesia evaluation period.

Preoperative anxiety is associated with anesthesia rather than demographic characteristics and surgical factors. Aykent et al.15 defined anxiety before surgery as the possibility of waking up during the operation and the fear of pain during the postoperative period, as well as the fear of being treated in intensive care after waking up. The fear of awakening during the operation was also taken into consideration in our study. We aimed to investigate the relationship between preoperative anxiety and preoperative ADA. Although some patients do not remember ADA, this situation creates many problems in the daily lives of patients. The development of awareness during general anesthesia harms patients, the anesthesia team, and the surgeon performing the operation. Severe depression and post-traumatic stress disorder occur in people who become aware during anesthesia. Patients who are forced to live with such situations may have increased levels of excitement and fear in subsequent operations.

Dreams during anesthesia are usually similar to dreams during sleep; they are short and pleasant and contain content from everyday life. In the literature, the incidence of dreaming varies with factors such as age, sex, the anesthesia technique applied, drugs, the severity of anesthesia and the postoperative interview time, but the incidence has a wide range of 1−81%.17 A study by Uting et al.18 reported that 7% of 500 patients had a bad dreaming experience and 2% remembered this experience. In our study, 10 (8%) patients had experienced dreams during previous operations, and these dreams did not have bad or unpleasant features.

Different rates of ADA have been revealed in various groups of patients. For example, the National Audit Project (NAP5) published in 2014 reported that the incidence of ADA in the United Kingdom was 1 in 19,000 (0.0052%) patients.19 However, in other studies, the incidence of ADA was estimated to be 0.2−0.3% during general anesthesia.20, 21 In the United States, this rate was 0.1−0.2%, and in Europe, it was 0.1% in neuromuscular blocker users and 0.18% in nonusers.6 In another study in Europe, this rate was 0.2−0.9%.7 In addition, due to the most striking explanation on this subject, the possibility of having a heart attack due to anesthesia is similar to the probability of experiencing ADA.22 In our study, 3 (0.37%) of 799 patients experienced ADA. These three patients did not have severe psychological problems, and they did not need psychiatric support or treatment. In addition to the social difference, we believe that this situation is caused by the fact that patients do not perceive their experiences of awareness during anesthesia as a complication but as a natural progression.

An increased incidence of ADA has been reported in some patients and surgical groups. ADA was seen in 1−43% of trauma patients, 0.4−1.3% of patients who underwent Cesarean Section (C/S), and 1.5−23% of patients who underwent Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG).23, 24, 25 In this study, one of the three patients who experienced ADA underwent open heart surgery (aortic valve replacement), one had a cesarean section, and the other had multiple traumas due to a traffic accident. Our results are consistent with the literature.

There are some limitations of this study. Although we found that the anxiety score was high in our patients with ADA experience, we could not reveal the relationship with preoperative anxiety because of the low number of patients with ADA. At the same time, we could not obtain data about previous anesthetic drug use or monitor this use in patients during their past operations, so we did not assess the relationship between ADA and anesthetic drugs. On the other hand, as our study was an observational study, randomized studies are needed on this subject.

Conclusion

It is important to determine the anxiety levels of patients during the preoperative period to prevent associated complications. It is also important to investigate and prevent the causes of ADA. However, we believe that in addition to preventing ADA, ADA should be questioned by anesthesiologists, should be taken into account at all times, and should be dealt with in a multidisciplinary manner. For this reason, during preoperative evaluations, ADA should be carefully questioned while evaluating previous anesthesia experiences. When experiences of awareness are suspected, the entire surgical team should be informed to prevent side effects due to high preoperative anxiety. We believe that larger studies on the effect of ADA on preoperative anxiety and studies about its treatment should be conducted.

Author’s contribution

SA designed the study and SA, COC collected the data, SA generated the first draft of paper, and JE generated the last draft of the paper. SA and COC performed the literature search. SA did the statistics.

Conflicts of interest

There is no financial relationship with a biotechnology and/or pharmaceutical manufacturer that has an interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the submitted manuscript. None of the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Lin C.J., Liu H.P., Wang P.Y., et al. The Effectiveness of Preoperative Preparation for Improving Perioperative Outcomes in Children and Caregivers. Behav Modif. 2019;43:311–329. doi: 10.1177/0145445517751879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aust H., Eberhart L., Sturm T., et al. A cross-sectional study on preoperative anxiety in adults. J Psychosom Res. 2018;111:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindler C.H., Harms C., Amsler F., et al. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients’ anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:706–712. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urfalioglu A., Arslan M., Bakacak M., et al. Efficacy of bispectral index monitoring for prevention of anesthetic awareness and complications during oocyte pick-up procedure. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:1583–1589. doi: 10.3906/sag-1609-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brice D.D., Hetherington R.R., Utting J.E. A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1970;42:535–542. doi: 10.1093/bja/42.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebel P.S., Bowdle T.A., Ghoneim M.M., et al. The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:833–839. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130261.90896.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandin R.H., Enlund G., Samuelsson P., et al. Awareness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study. Lancet. 2000;355:707–711. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)11010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oner N., LeCompte A. 1 ed. Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayını; İstanbul: 1983. Durumluk − Sürekli Kaygı Envanteri El Kitabı; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aranake A.G.S., Ben-Abdallah A., Lin N., et al. Increased risk of intraoperative awareness in patients with a history of awareness. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1275–1283. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tasdemir A.E.A., Deniz M.N., Certug A. Comparison of Preoperative and Postoperative Anxiety Levels with State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Test in Preoperatively Informed Patients. Turk J Anaesth Reanim. 2013;41:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caumo W., Schmidt A.P., Schneider C.N., et al. Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:298–307. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045003298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moerman N., van Dam F.S., Muller M.J., et al. The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) Anesth Analg. 1996;82:445–451. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghoneim M. The trauma of awareness: history, clinical features, risk factors, and cost. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:666–667. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cb5dfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabow L., Buse R. Preoperative anxiety−anxiety about the operation, anxiety about anesthesia, anxiety about pain? Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1990;40:255–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aykent R.K.İ, Üstün E., Tür A., et al. Preoperatif anksiyete nedenleri ve değerlendirilmesi: APAİS ve STAİ Skorlarının Karşılaştırılması. Türkiye Klinikleri J Anest Rean. 2007;5:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egbert Ld, Battit G., Turndorf H., et al. The value of the preoperative visit by an anesthetist. A study of doctor-patient rapport. JAMA. 1963;185:553–555. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060070021016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu G., Liu X., Sheng Q., et al. Sex differences in dreaming during short propofol sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Neuroreport. 2013;24:797–802. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283644b66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Utting J.E. The era of relaxant anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:551–553. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandit J.J., Andrade J., Bogod D.G., et al. 5th National Audit Project (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia: summary of main findings and risk factors. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:549–559. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham M., Owen A.M., Cipi K., et al. Minimizing the Harm of Accidental Awareness Under General Anesthesia: New Perspectives From Patients Misdiagnosed as Being in a Vegetative State. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1073–1076. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mashour G.A., Avidan M.S. Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:i20–i26. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domino K.B.P.K., Caplan R.A., Cheney F.W. Awareness during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1053–1061. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199904000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghoneim M.M. Awareness during anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:597–602. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serfontein L. Awareness in cardiac anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:103–108. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328334cb75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons G., Macdonald R. Awareness during caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:62–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]