Abstract

Background and objectives

PECS I block was first described for surgery involving the pectoralis muscles. No randomized clinical trial has been conducted on surgeries that directly involve these muscles, such as subpectoral breast augmentation. We hypothesized that PECS I block would decrease pain in the postoperative period in this population.

Methods

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in women undergoing subpectoral breast augmentation surgery. PECS I block was performed using 0.4 mL.kg-1 of 0.9% saline on one side and bupivacaine (0.25%) on the other side, each patient being her own control. Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain scores (0 − 10) were measured at rest and during movement. The primary outcome was pain score at rest 30 minutes after arrival in the PACU. To detect a clinically significant difference of 50% in pain reduction, 14 volunteers were enrolled (power of 90% and alpha < 0.05).

Results

In the PACU, three patients had no difference in pain between sides, five had reduced pain on the placebo side, and six had reduced pain on the bupivacaine side. In the bupivacaine group, pain scores at rest at 5, 30 and 60 minutes and 24 hours were 4.89 (4.23 − 5.56; mean 95% CI), 3.75 (3.13 − 4.37), 3.79 (2.93 − 4.64), and 2.29 (1.56 − 3.01), respectively, whereas in the placebo group, they were 4.96 (4.32 − 5.60), 4.00 (3.50 − 4.49), 3.93 (3.12 − 4.73), and 2.29 (1.56 − 3.01), respectively.

Conclusions

PECS I block in patients undergoing breast augmentation surgery does not provide better pain relief than placebo. Therefore, the indications for PECS I block in breast augmentation surgery should be reconsidered.

Keywords: Breast augmentation, Regional anesthesia, Nerve block, PEC block

Resumo

Justificativa e objetivos

O bloqueio PECS I foi descrito pela primeira vez para cirurgia envolvendo os músculos peitorais. Nenhum estudo clínico randomizado foi realizado em procedimentos envolvendo diretamente os músculos peitorais, como a mamoplastia de aumento submuscular. Nossa hipótese foi de que o bloqueio PECS I diminuiria a dor pós-operatória nessa população.

Método

Realizamos estudo randomizado, duplo-cego, controlado por placebo em mulheres submetidas à mamoplastia de aumento submuscular. Realizamos o bloqueio PECS I com 0,4 mL.kg-1 de solução salina a 0,9% de um lado e bupivacaína (0,25%) do outro lado, sendo cada paciente seu próprio controle. Os escores da Escala de Avaliação Numérica (EAN) de dor (0 − 10) foram obtidos em repouso e durante movimento. O desfecho primário foi o escore de dor em repouso 30 minutos após a chegada à SRPA. Para detectar uma diferença clinicamente significante de 50% na redução da dor, 14 voluntárias foram incluídas (poder de 90% e alfa < 0,05).

Resultados

Na SRPA, três pacientes não apresentaram diferença na dor entre os lados, cinco relataram menos dor no lado do placebo, e seis menos dor no lado da bupivacaína. No grupo bupivacaína, os escores de dor em repouso aos 5, 30 e 60 minutos e 24 horas foram 4,89 (4,23 − 5,56; IC médio 95%), 3,75 (3,13 − 4,37), 3,79 (2,93 − 4,64) e 2,29 (1,56 − 3,01), respectivamente, enquanto no grupo placebo foram 4,96 (4,32 − 5,60), 4,00 (3,50 − 4,49), 3,93 (3,12 − 4,73) e 2,29 (1,56 − 3,01), respectivamente.

Conclusões

O bloqueio PECS I em pacientes submetidas à mamoplastia de aumento não oferece melhor alívio da dor do que o placebo. Portanto, as indicações para bloqueio de PECS I na cirurgia de aumento de mama devem ser reconsideradas.

Palavras-chave: Mamoplastia de aumento, Anestesia regional, Bloqueio de nervos, Bloqueio PEC

Introduction

The Pectoral I (PECS I) block was first described by Blanco in 2011.1 This technique consists of the injection of local anesthetics in the plane between the pectoralis major and minor muscles in order to achieve a block of the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. Since these nerves mostly innervate the pectoralis muscles, the PECS I block is theoretically suited for surgery involving these muscles. In 2012, a modified version of the block was proposed by the same author, called the PECS II block. It is done by adding another, deeper injection in the plane between the pectoralis minor and the serratus anterior muscle.2 This technique is believed to contribute to a more extensive anesthesia of the chest wall by also blocking the long thoracic nerve and the lateral branches of the intercostal nerves from T3 to T6.

Since the description of the PECS II block, the vast majority of published articles have evaluated the efficacy of this modified technique. This block appears to offer an analgesic advantage for mastectomy and lumpectomy, with a statistically significant diminution of Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain score and less consumption of analgesic during the postoperative period.3, 4, 5 However, very few studies have specifically evaluated the interpectoral injection (PECS I block).6, 7, 8

Subpectoral breast augmentation is associated with significant pain in the immediate postoperative period9 and with moderate to severe chronic pain in up to 9.5% of patients.10 Pectoral muscle distension and spasms can possibly contribute to the pain associated with this surgery.11 The best analgesic regimen for breast augmentation is still unclear.12

The PECS I block could be the ideal complement of a multimodal analgesic regimen for subpectoral breast augmentation because of the direct trauma this procedure delivers to the pectoral muscles and their significant distension. No study has specifically evaluated its efficacy for this type of surgery. This study is a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on PECS I block for subpectoral breast augmentation surgery. We hypothesized that PECS I block would be associated with less pain in the Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU) compared to placebo.

Methods

Following ethics committee approval, registration at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT-03040167) and obtaining written informed consent, we proceeded with randomization of 14 female adults undergoing subpectoral breast augmentation. Exclusion criteria were as follows: patient refusal, allergy to bupivacaine, coagulopathies, local infection, pregnancy, breastfeeding, chronic pain, and muscle relaxant or chronic analgesic use prior to breast surgery. Recruitment took place in a private clinic (Clinique Chirurgicale de Laval, Laval, Canada) from November 2017 to February 2018.

On the morning of surgery, all patients received oral celecoxib 100 mg and acetaminophen 1 g. The patients were placed under standard monitoring and intravenous sedation with propofol (20 − 30 mg), and remifentanil (30 − 45 µg) was used to perform the PECS I block. Bilateral PECS I blocks were performed by the same anesthesiologist (JD) using a 4 − 12 MHz linear probe (GE Logic E, Jiangsu, China).

After sterile preparation and disinfection of the thoracic skin area, the probe was placed obliquely under the clavicle, perpendicular to the principal axis of the pectoral minor muscle. The medial end of the probe was angulated cephalad to nearly touch the clavicle, while the lateral end was positioned more caudally. An 80 mm echogenic short bevel needle (SonoTAP, Pajunk, Geisingen, Germany) was then introduced in-plane caudo-lateral to the cranio-medial axis. The needle tip was placed between the pectoral major and minor muscles close to the pectoral branch of the thoraco-acromial artery. A solution of 0.4 mL.kg-1 bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine 2.5 µg.mL-1 or 0.4 mL.kg-1 of 0.9% NaCl (placebo) was then randomly injected, one side assigned to the placebo and the other side to the local anesthetic solution. Each patient therefore served as its own control. The syringes used in the study were prepared by a technician not involved in patient care or evaluation and were only identified as for the left side or right side. The randomization was performed using an online randomization tool (Random.org).

After the block, the induction of general anesthesia was standardized with intravenous propofol 2 − 3 mg.kg-1 and remifentanil 1 − 2 µg.kg-1. If the patient had no contraindication, airway management consisted of the insertion of a laryngeal mask (Solus, Intersurgical, Wokingham, UK) and ventilation with an air/oxygen mixture that was adjusted for an expired CO2 between 35 and 45 mmHg and oxygen saturation over 95%. Intravenous infusions of propofol (100 − 200 µg.kg-1. min-1) and remifentanil (0.1 − 0.2 µg.kg-1. min-1) were used for maintenance of anesthesia, with dose adjustment for a BIS (BIS, Covidien, Mansfield, USA) between 40 and 60. All patients received dexamethasone 5 mg at induction of anesthesia and ondansetron 4 mg at the end of surgery to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. Antibiotics were also administered (cefazolin 2 g or other agent if an allergy was reported by the patient) at least five minutes before skin incision. At the end of surgery, to ensure transitional analgesia after remifentanil infusion, sufentanil 0.2 µg.kg-1 was administered.

Bilateral breast augmentation was performed by a single plastic surgeon (BL), using Allergan Inspira round smooth silicone cohesive gel implants (moderate and full profile). A subpectoral pocket was used for implant placement. Pectoralis major surgical release was performed with electrocautery in the inferomedial area, equivalent to the type I dual-plane technique described by Tebbetts.13 During the procedure, the surgeon was asked to assess whether a difference in relaxation of the pectoral muscles was noticed between the left and right sides.

After the end of the surgery, the patient was brought to the PACU. There, pain scores at rest and with movement (arm adduction) were evaluated for each side with a numeric rating scale (NRS; 0 − 10) every five minutes for 30 minutes and at 60 minutes. If any operated side had a pain score of 5 or more, fentanyl 25 µg was administered, and it could be repeated every five minutes up to a maximum dose of 150 µg. Every patient received tramadol 100 mg 30 minutes after arrival in the PACU to ensure a longer-lasting analgesic effect. A prescription of oral hydromorphone was given to the patient after discharge from the clinic. A follow-up telephone call was made 24 hours after the surgery to assess the presence of complications and to evaluate the approximate duration of unilateral analgesia, if present. The primary outcome was pain score at rest 30 minutes after arrival in the PACU for both operated sides. Secondary outcomes consisted of pain scores at rest and with movement at five minutes, 30 minutes (with movement), 60 minutes and 24 hours after arrival in the PACU, as well as the presence of block complications (hematoma, bleeding) and nausea and vomiting postoperatively.

Statistical analysis

The number of patients was calculated using the sample size formula for a paired t-test. The patients being their own controls, in order to demonstrate a clinically significant difference of 50% in pain reduction (from an NRS of 5 to 2.5 with an estimated standard deviation [SD] of 2.5), with a power of 90% and an alpha of 5%, 14 volunteers were enrolled. The expected pain value of 5 on the NRS was based on the mean value of pain after breast augmentation of 5.54 in the study of Gerbershagen.9 Data on the anesthetic block were tested for normality and equality of variances using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests (before and after). Pain scores were compared between groups using Student’s t-test for matched samples, p < 0.05 was the level for significance.

Results

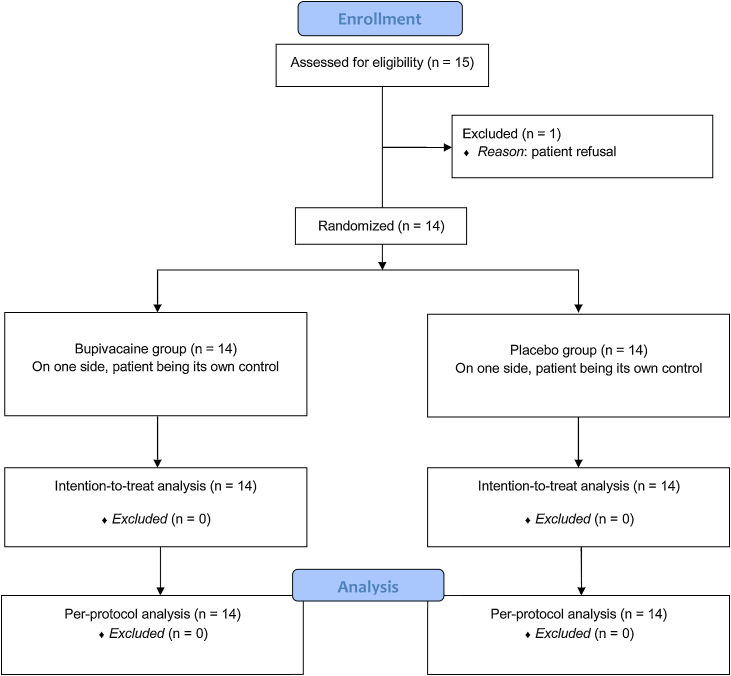

Fourteen subjects were recruited over a period of four months (Fig. 1). The baseline demographic data and characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The volume of local anesthetic or placebo injected was 23.0 ± 1.7 mL in each side. The mean duration of surgery was 65.8 ± 9.3 minutes. The patients received a total of 759.3 ± 142.8 mg of propofol and 719.3 ± 176.8 μg of remifentanil for induction and maintenance of anesthesia.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data and characteristics of study participants (mean ± SD).

| Study participants (n = 14) | |

|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years) | 36.0 ± 8.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.4 ± 4.7 |

| Height (cm) | 161.0 ± 6.0 |

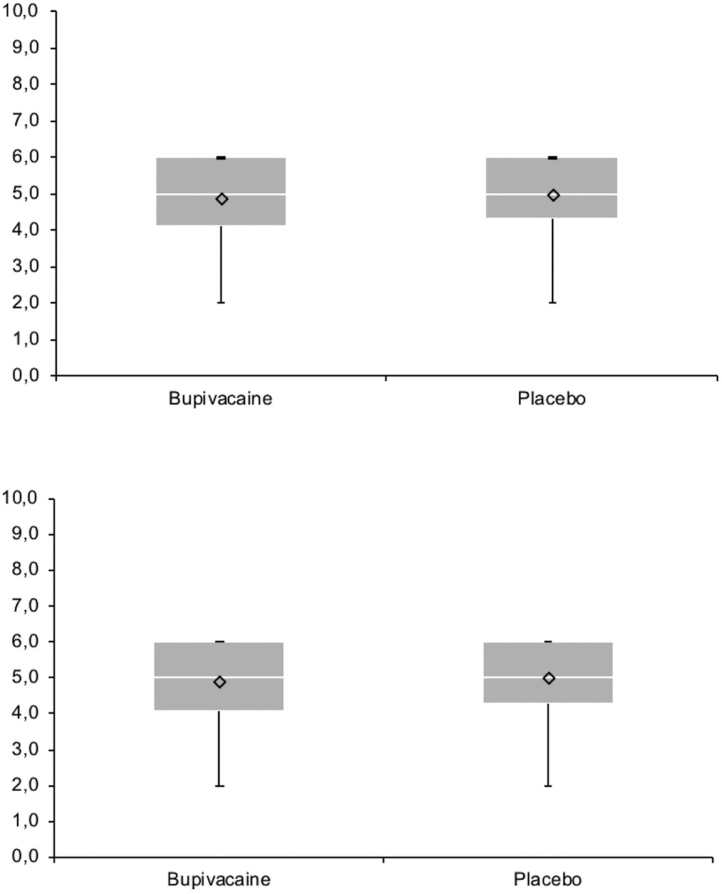

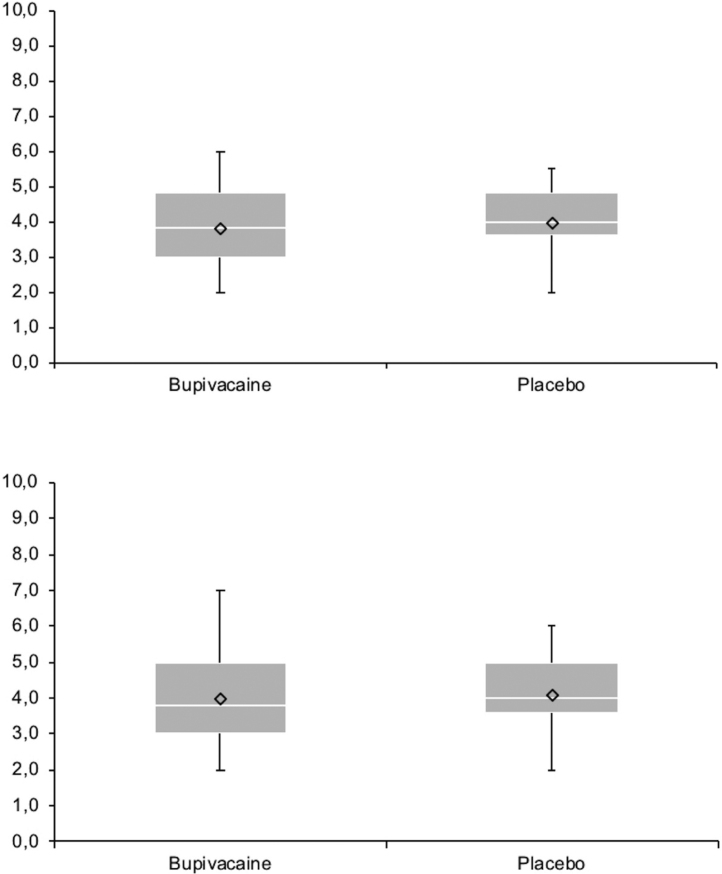

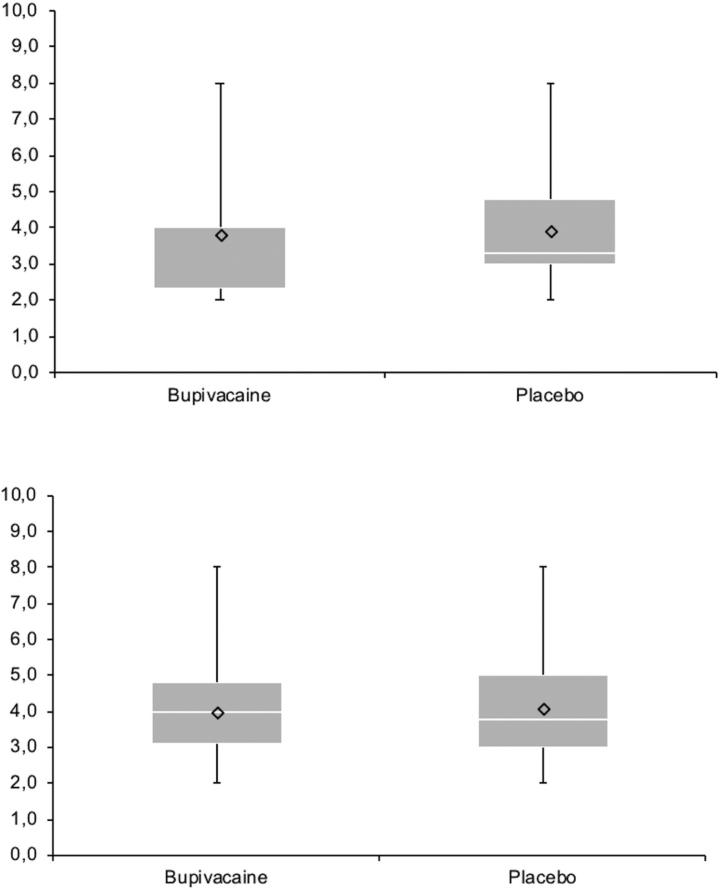

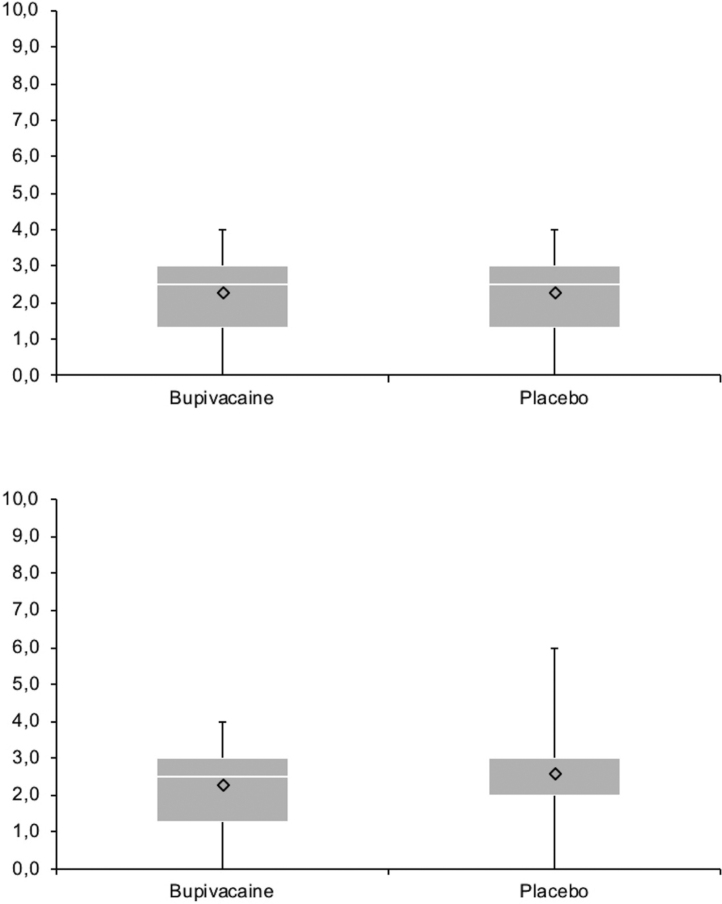

During the procedure, the plastic surgeon noted a difference between pectoral muscle relaxation in all patients but correctly identified the side injected with bupivacaine in only eight patients (57%). In the PACU, three patients had no difference in pain between sides, 5 had reduced pain on the placebo side, and six had reduced pain on the bupivacaine side. In the bupivacaine group, pain scores at rest at 5, 30 and 60 minutes and 24 hours were 4.89 (4.23 − 5.56; 95% mean CI), 3.75 (3.13 − 4.37), 3.79 (2.93 − 4.64), and 2.29 (1.56 − 3.01), respectively, whereas in the placebo group, they were 4.96 (4.32 − 5.60), 4.00 (3.50 − 4.49), 3.93 (3.12 − 4.73), and 2.29 (1.56 − 3.01), respectively (Fig. 2A, Fig. 3A, Fig. 4A and Fig. 5A). Similarly, pain scores with movement were not significantly different between the bupivacaine and the placebo side (Fig. 2B, 3B, 4B and 5B). Patients received a total of 115.38 ± 34.67 µg of fentanyl in the PACU before discharge. No complications related to the PECS I block were reported.

Figure 2.

Pain scores (NRS) at rest (A) and during movement (B) 5 minutes after arrival in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU).

Figure 3.

Pain scores (NRS) at rest (A) and during movement (B) 30 minutes after arrival in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU).

Figure 4.

Pain scores (NRS) at rest (A) and during movement (B) 60 minutes after arrival in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU).

Figure 5.

Pain scores (NRS) at rest (A) and during movement (B) 24 hours after the surgery.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that PECS I block in patients undergoing breast augmentation surgery does not provide better pain relief than placebo when the patient acts as her own control. This result is found up to 24 hours postoperatively, for pain at rest and with movement.

Since the description of PECS I block, some confusion remains regarding its clinical indication. Blanco considered that this block could be an alternative to paravertebral block and thus be useful for breast tissue surgeries.1 Woodworth and colleagues14 have recently published indications of truncal blocks for breast surgeries based on anatomical knowledge of breast innervation. These authors suggested that PECS I block should be used for interventions involving the pectoral muscles, such as subpectoral breast augmentation, and not for surgeries involving breast tissue, such as partial and total mastectomy. Until now, the clinical benefits of the PECS I block for this type of surgery have not been scientifically demonstrated.

In fact, only three studies, with conflicting results, have evaluated the PECS I block. Abdallah and colleagues7 published a retrospective study comparing PECS I block to a serratus block and to a control procedure in patients undergoing breast cancer surgeries. PECS I block was associated with reduced in-hospital opioid consumption and postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to control. More recently, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Cros and colleagues evaluated PECS I block for breast cancer surgeries.8 No significant difference was observed in pain score between bupivacaine and placebo groups. Goswani and colleagues compared PECS I vs. a modified PECS II performed between the pectoralis minor and the serratus anterior for postoperative pain in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy.6 The blocks were done with a catheter placed by the surgeon in the designated muscle plane at the end of surgery. Analgesia was significantly prolonged in the modified PECS II group compared to that in the PECS I group. One can hypothesize that use of the PECS I block in the Abdallah and Cros studies may not have been optimal since the pectoral muscles were not directly involved in the surgical trauma. We must recognize that even if the PECS I block is designed to anesthetize the pectoral nerves, the local anesthetics injected between the pectoralis major and minor muscles may extend laterally and block the lateral branches of the intercostal nerves.15 It is not known if this lateral extension of the local anesthetics occurs during all breast surgeries or only those involving the axilla with its accompanying fascia disruption. Therefore, a broader analgesia involving the cutaneous tissues could explain the positive results in the study of Abdallah and colleagues.7

The pectoral nerves are considered mainly motor nerves.16 They innervate the pectoralis major and minor muscles, the main adductors of the upper limb.17 A previous randomized, double-blind, controlled study conducted by our group evaluated the sensitive and motor effect of the PECS I block on six healthy volunteers.18 The same technique, solution and volume as in the present study were used. There was no difference in skin sensory testing on the anterior thorax at evaluation, but a significant reduction in adduction strength of the upper limb was objectively observed (measured with a hand-held dynamometer). That study was the first and only one that has objectively shown that a PECS I block is capable of effectively blocking the pectoral nerves. Even though it only involved six volunteers, we obtained a success rate of 100% with the same block technique as in this study. We believe that the technical success of the PECS I is high because of the high volume used and the consistent endpoint of the injection, i.e., the pectoral branch of the thoraco-acromial artery. Therefore, the PECS I block should be able to produce analgesia for surgeries in which postoperative pain is caused by pectoralis muscle involvement, such as subpectoral breast augmentation.

However, the physiopathology of pain after this surgery is still speculative and probably involves multiple mechanisms. In addition to the skin trauma, the pain has often been ascribed to pectoralis muscle distension or spasm, but this remains hypothetical.11, 19 Other sources of pain, such as sternal and interscapular discomfort, have also been described,20 as has pain from the serratus anterior muscle.14

Our hypothesis was that pain associated with subpectoral breast augmentation comes from pectoral muscle trauma and is mediated by the pectoral nerves. Our negative results might mean that the innervation and, therefore, the blocking of pectoral nerves are more complex than usually described. Furthermore, a single interpectoral injection may not block all of the medial and pectoral nerves and their branches. The pectoralis major muscle is usually described as being subdivided into a clavicular and a sternocostal head. The clavicular portion is supplied by the lateral pectoral nerve, with four to seven branches. The sternocostal portion of the pectoralis major muscle and the pectoralis minor muscle are supplied by the medial pectoral nerve, which travels under the pectoral minor muscle, giving off a variable number of branches that pierce the pectoral minor muscle.16 The classic single interpectoral injection of the PECS I block may not block the medial pectoral nerve or all of its perforating branches. It is with this reasoning that a different pectoral nerve block has been developed in a cadaver study.21 The technique consists of a triple injection to block as completely as possible the lateral and medial pectoral nerves and its branches. Schuitemaker and colleagues have also modified the pectoral nerve block in an attempt to provide analgesia for clavicle surgery.22 In their case series, the authors modified the pectoral block by injecting 8 mL of local anesthetics posterior to the pectoralis minor muscle, 2 mL in the thickness of this muscle to block the medial pectoral nerve and its perforating branches, and finally, 10 mL in the interpectoral space to block the lateral pectoral nerve. This approach produced good analgesia by blocking both pectoral nerves that supply part of the clavicle. These authors had previously not obtained good analgesia for this type of surgery with a classic PECS I block because they considered that it blocked selectively the lateral pectoral nerve.

Therefore, there is no doubt that PECS I does block, at least in part, the lateral pectoral nerve, as demonstrated by a reduction in the upper limb adduction strength.18 It does not, however, mean that the pectoralis major muscle is entirely blocked; it could be only the clavicular part, being the most important in the functionality of the shoulder.17

Another possibility to explain the absence of analgesia with PECS I block in subpectoral breast augmentation is that the cutaneous or glandular tissues are the main contributors to the painful stimulus. This fact could explain the results of some studies where breast augmentations were done using only a paravertebral block, without general anesthesia.23 A recent study by Karaca and colleagues evaluated the PECS II block in comparison to placebo in subpectoral breast augmentation.24 Their study demonstrated a significant diminution in visual analog scale pain score from admission to the PACU up to 24 hours later and less fentanyl consumption during this period. These results confirm that the PECS II block can be considered part of a multimodal analgesic regimen for breast augmentations.

However, with the negative results of our study, we can hypothesize that only the injection between the pectoralis minor and the serratus anterior muscle contributes to the analgesic benefit of the PECS II block and that only this injection explains their positive results. The benefit of the injection between pectoralis minor and serratus anterior in the PECS II block has been shown in a study by Quek and colleagues.25 They demonstrated that this injection produces a block of the intercostobrachial nerve that is spared when doing a brachial plexus block for proximal arteriovenous access.

For other types of breast surgeries, the PECS II block appears to be more widely used than PECS I, based on the number of clinical studies published.3, 4, 5, 26, 27 The PECS II block has been used primarily for breast cancer surgeries, with favorable results compared to those of the control groups, as confirmed by two recent meta-analysis.28, 29 These surgeries involve mostly cutaneous and glandular structures that are innervated by the intercostal nerves. Here, again, the second injection appears to explain the analgesic benefit obtained by the PECS II block.

When considering a block for breast surgery, the results of the recent literature, including our study, suggest that the interpectoral injection of the PECS II block, i.e., the PECS I block, is of limited value. We can therefore hypothesize that an injection between the pectoralis minor and the serratus anterior, or alternatively a serratus anterior plane block, is of greater benefit. Further studies are necessary to confirm the clear indications and benefits of these blocks.

There are some limitations to our study. First, only 14 patients were involved, but being their own controls, this is approximately equivalent to having recruited 45 patients if a parallel study design had been used. Our small sample size is similar to the 12 patients included in a study evaluating a local infiltration analgesia technique in a placebo-controlled, randomized, and double-blind trial in bilateral knee arthroplasty.30 That study and ours had a design that took advantage of the patient being their own control and that included a placebo injection on one side. Both studies involved painful surgery, and both evaluated a novel regional technique to produce a significant pain reduction. The pain score in Andersen’s study was reduced by more than 50% in the first 8 hours. Before promoting a new regional block such as PECS I in clinical practice, we should be able to demonstrate a major reduction in pain score in a study such as ours where each patient is her own control. In this context, we believe that it is not appropriate to evaluate the outcome in the form of a Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) in pain score of 10 mm on the 100 mm pain VAS.31 The use of MCID for pain scores could be meaningful when evaluating two different analgesic modalities, for example. The fact that the patients were their own controls to assess postoperative pain strengthens our study, but on the other hand, the patients may have been slightly sleepy or confused in the PACU and may not have been able to properly assess which side their pain was mostly coming from. Furthermore, it would have been of interest to objectively evaluate the success of our block by showing a reduced upper limb adduction strength on the side where the local anesthetic was injected, but this would have unblinded the patients, and our volunteer study has already shown the high success rate of our technique.18

Summary

In conclusion, and contrary to current opinion, PECS I block performed in patients undergoing breast augmentation surgery does not provide better pain relief than that of the placebo when patients are their own control. This finding applies throughout the postoperative period up to 24 hours, for pain at rest and during movement. Other recent studies8, 18 tend to confirm these results. Therefore, the indications for PECS I block in breast augmentation surgery and even in breast cancer surgery should be reconsidered. Finally, its value as the first injection as part of the PECS II block should also be addressed in future studies.

Funding

The authors have no external sources of funding to declare for this manuscript but were supported by a departmental fund from the Department of Anesthesiology of St Jérôme Hospital, Quebec, Canada.

Conflicts of interest

Dr B. LeBlanc has received fees for a medical conference in 2017 with Allergan Inc.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the SFAR meeting in Paris (September 27−28th, 2018) by Maxim Roy and at the IARS World Congress of Pain in Boston (September 12−16th, 2018) by Pierre Beaulieu.

References

- 1.Blanco R. The’ PECS block’: a novel technique for providing analgesia after breast surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:847–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco R., Fajardo M., Parras Maldonado T. Ultrasound description of PECS II (modified PECS I): a novel approach to breast surgery. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2012;59:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashandy G.M., Abbas D.N. Pectoral nerves I and II blocks in multimodal analgesia for breast cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:68–74. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulhari S., Bharti N., Bala I., et al. Efficacy of pectoral nerve block versus thoracic paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia after radical mastectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:382–386. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ELdeen H.M.S. Ultrasound guided pectoral nerve blockade versus thoracic spinal blockade for conservative breast surgery in cancer breast: a randomized controlled trial. Egypt J Anaesth. 2016;32:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goswami S., Kundra P., Bhattacharyya J. Pectoral nerve block 1 versus modified pectoral nerve block2 for postoperative pain relief in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:830–835. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdallah F.W., MacLean D., Madjdpour C., et al. Pectoralis and serratus fascial plane blocks each provide early analgesic benefits following ambulatory breast cancer surgery: a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:294–302. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cros J., Senges P., Kaprelian S., et al. Pectoral i block does not improve postoperative analgesia after breast cancer surgery: a randomized, double-blind, dual-centered controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:596–604. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerbershagen H.J., Aduckathil S., Van Wijck A.J., et al. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:934–944. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828866b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Sperling M.L., Hoimyr H., Finnerup K., et al. Persistent pain and sensory changes following cosmetic breast augmentation. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Layeeque R., Hochberg J., Siegel E., et al. Botulinum toxin infiltration for pain control after mastectomy and expander reconstruction. Ann Surg. 2004;240:608–613. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141156.56314.1f. discussion 13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley S.S., Hoppe I.C., Ciminello F.S. Pain control following breast augmentation: a qualitative systematic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32:964–972. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12457014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tebbetts J.B. Dual plane breast augmentation: optimizing implant-soft-tissue relationships in a wide range of breast types. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1255–1272. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200104150-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodworth G.E., Ivie R.M.J., Nelson S.M., et al. Perioperative breast analgesia: a qualitative review of anatomy and regional techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:609–631. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sleth J.C. Pecs block in breast surgery: in fact a simple intercostal block? Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2014;33:548. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porzionato A., Macchi V., Stecco C., et al. Surgical anatomy of the pectoral nerves and the pectoral musculature. Clin Anat. 2012;25:559–575. doi: 10.1002/ca.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barberini F. The clavicular part of the pectoralis major: a true entity of the upper limb on anatomical, phylogenetic, ontogenetic, functional and clinical bases. Case report and review of the literature. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2014;119:49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desroches J., Belliveau M., Bilodeau C., et al. Pectoral nerves I block is associated with a significant motor blockade with no dermatomal sensory changes: a prospective volunteer randomized-controlled double-blind study. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:806–812. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govshievich A., Kirkham K., Brull R., et al. Novel approach to intractable pectoralis major muscle spasms following submuscular expander-implant breast reconstruction. Plast Surg Case Studies. 2015;1:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacik P.T. Pain management in augmentation mammaplasty: a randomized, comparative study of the use of a continuous infusion versus self-administration intermittent bolus of a local anesthetic. Aesthet Surg J. 2004;24:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desroches J., Grabs U., Grabs D. Selective ultrasound guided pectoral nerve targeting in breast augmentation: How to spare the brachial plexus cords? Clin Anat. 2013;26:49–55. doi: 10.1002/ca.22117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuitemaker J.B., Sala-Blanch X., Rodriguez-Pérez C.L., et al. The PECS II block as a major analgesic component for clavicle operations: a description of 7 case reports. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2018;65:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooter R.D., Rudkin G.E., Gardiner S.E. Day case breast augmentation under paravertebral blockade: a prospective study of 100 consecutive patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:666–673. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karaca O., Pinar H.U., Arpaci E., et al. The efficacy of ultrasound-guided type-I and type-II pectoral nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia after breast augmentation: a prospective, randomised study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quek K.H., Low E.Y., Tan Y.R., et al. Adding a PECS II block for proximal arm arteriovenous access − a randomised study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:677–686. doi: 10.1111/aas.13073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Versyck B., van Geffen G.J., Van Houwe P. Prospective double blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of the pectoral nerves (PECS) block type II. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahba S.S., Kamal S.M. Thoracic paravertebral block versus pectoral nerve block for analgesia after breast surgery. Egypt J Anaesth. 2014;30:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovett-Carter D., Kendall M.C., McCormick Z.L., et al. Pectoral nerve blocks and postoperative pain outcomes after mastectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;44:923–928. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2019-100658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Versyck B., Van Geffen G.J., Chin K.J. Analgesic efficacy of the PECS II block: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2019;74:663–673. doi: 10.1111/anae.14607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen L.Ø, Husted H., Otte K.S., et al. High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2008;52:1331–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myles Ps, Myles Db, Galagher W., et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:424–429. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]