Abstract

Background and objectives

Neuropathic pain is common in the general population worldwide and Brazil. The painDETECT questionnaire is a notable instrument for screening on neuropathic pain. A Brazilian version of the painDETECT is necessary to broaden the possibilities of identification of neuropathic pain in the Brazilian population for the proper diagnosis and treatment. The current study aimed to perform the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the painDETECT into the Portuguese language of Brazil.

Methods

A cross-cultural adaptation study was conducted in 11 stages according to standard procedures. Descriptive statistics were performed. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha test (α).

Results

Four translators, 10 experts, and 30 patients participated in the study. The expert committee adapted five out of nine items (item 2, 3, 6, 8, and 10) to the Brazilian context. The pretesting phase showed good internal consistency (α = 0.74) for the nine items, including the pain pattern and the body chart domains. The Cronbach’s α of the instrument with seven descriptor items of pain was 0.83.

Conclusions

The painDETECT was cross-culturally adapted into a Brazilian context and can be used to identify neuropathic components in pain of Brazilian patients.

Clinical implications

PainDETECT is available for Brazilians to identify neuropathic components in pain.

Keywords: Neuropathic pain, Rehabilitation, Validation studies, Psychometrics

Introduction

A neuropathic pain component is common in individuals with chronic pain and accounting for 6.9% of the general population.1 A neuropathic component is present in 35% of the pain syndromes2 and 37% of the patients with chronic low back pain.3 In Brazil, 10% of the population present chronic pain with neuropathic features.4 There are some screening tools (i.e., Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions – DN4 and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs – LANSS) capable of identifying key symptoms and signs related to neuropathic pain.3 The painDETECT questionnaire is, of the existing tools, one of the best options for screening neuropathic pain (sensitivity = 85% and specificity = 95%).5

The painDETECT is a self-administered questionnaire that encompasses four domains. The first domain includes three questions that assess the intensity of pain. The second domain entails four graphs asking about the pain course pattern. The third domain comprises a body chart on which to draw the main areas of pain and the presence of radiating pain. The fourth domain has seven questions addressing seven sensory descriptor items of pain. For each question, six different answers are possible, with scores from zero (never) to five (very strongly). By summing up the scores given in each domain, a final score between -1 to 38 can be achieved.

The painDETECT has been validated for a large number of neuropathic pain conditions. In the recent last years it was also validated for the use in mixed pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, cancer pain, and lumbar spondylolisthesis.6 The cut-off points for the original questionnaire indicate that in scores ≤ 12 a neuropathic component is unlikely, whereas in the ≥ 19 scores a neuropathic component is probable.3, 6 The painDETECT has been translated and validated into more than 40 languages, including Portuguese. However, some items are not adequately described for Brazilians due to cultural aspects.

A Brazilian version of the painDETECT is necessary to broaden the options of neuropathic pain diagnosis and treatment in the Brazilian population. PainDETECT has the advantage to be self-reported compared to other two other instruments (i.e., DN4 and LANSS) available to assess neuropathic pain in the Brazilian population. Besides, screening questionnaires are useful to detect neuropathic pain in various medical settings, especially for non-specialists.7 Therefore, the primary objective of the study was to perform the linguistic translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the painDETECT into the Portuguese language of Brazil as a first step.

Methods

Study design

A translation and cross-cultural adaptation study were conducted under the supervision of an expert panel following the recommendations of the ISPOR guidelines, as they provide clear recommendations and a detailed multistep approach.8 Ethics approval was provided by an Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (number 02228818.0.3001.5258). All participants provided informed consent before participation.

Procedures

The English version of the questionnaire was first sent to two experienced forward translators after receiving permission from the questionnaire’s authors. One of them is a native of the Portuguese language and fluent in English, and the other is a native translator of the English language and fluent in the Portuguese language of Brazil. The reconciled version was then sent to two independent back-translators with the same credentials as the forward translators but who were not involved in the initial translation phase. Open questions were resolved through discussion within the expert panel, which compared the content of the harmonized version with the English version. Items with less than 80% agreement were changed in their wording until all members reach agreement. The committee reached agreement on the semantic, idiomatic, and conceptual equivalence between the English version and a final version of the questionnaire provided. Modifications were made to maintain a simple and clear language for the Brazilian context without changing the genuine meaning of the individual questions. Face validity through cognitive debriefing was performed during pretesting using guide questions.

A pretesting phase was conducted with 30 patients with musculoskeletal disorders recruited from the physiotherapy department of Gaffrée and Guinle University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, and Santa Casa de Misericordia de São Paulo, São Paulo. The consecutive patients over 18 years of age were enrolled when they sought treatment between March and September 2019. The study included patients with acute pain (pain duration less than three months) and chronic pain (pain duration greater than three months). Musculoskeletal pain was defined as pain perceived in a region of the body with muscular, ligament, bone, or joint origin.9 The study excluded patients who had a surgical procedure in the spine, pregnant women, patients with rheumatologic diagnosis in the acute inflammatory phase, tumors, were illiterate, or could not complete the self-reported questionnaires. The painDETECT questionnaire was self-administered, and after the pretesting evaluation, each subject was interviewed by the researcher about their understanding of the items and suggestions for improvement to the questionnaire. All participants completed the painDETECT questionnaire with no adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha test (α). The level of significance was set at 5% (p < 0.05). The statistical analysis was performed in the program SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

Results

Four physical therapists with experience in musculoskeletal pain, one physical therapist from pain management, one physical therapist with expertise in neurorehabilitation, two neurologists, and two translators formed the expert committee who analyzed the T1 e T2 version of the painDETECT questionnaire. The tool was adapted considering their comments and suggestions in five out of nine items (item 2, 3, 7, 8, and 10) to better adjust the content of the instrument to the Brazilian context. The modification process of the Brazilian version of the painDETECT is presented in the Supplementary Table 1. The remaining items obtained consensus, and a single version was produced (EV).

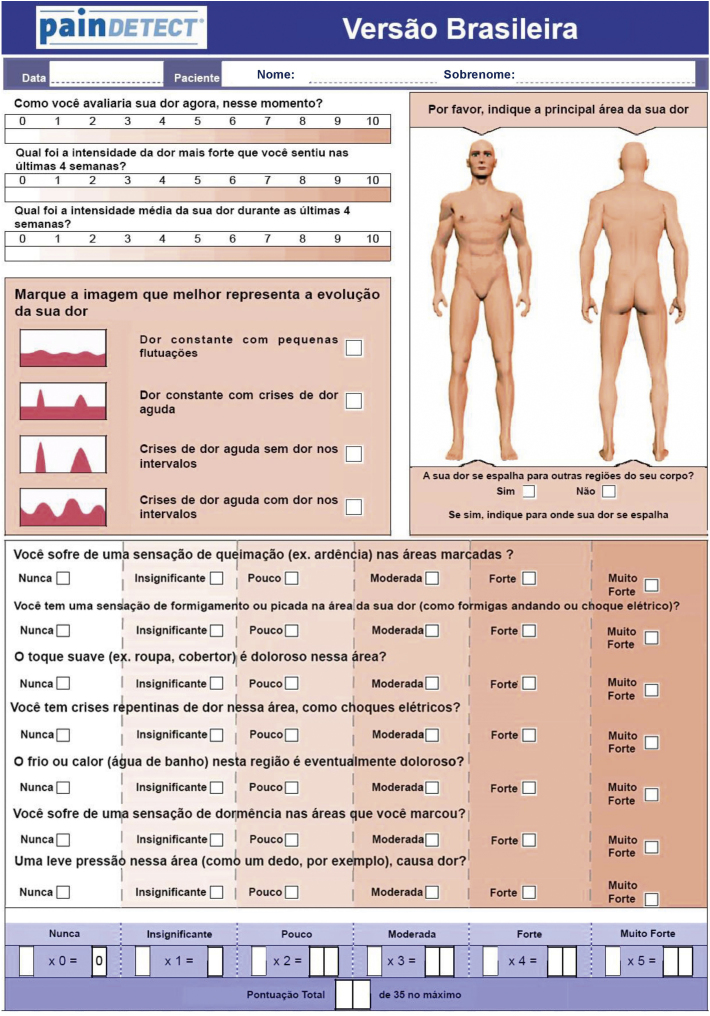

Participants understood most of the questions correctly, except the “insignificant” alternative, indicating confidence in the accuracy of their answers and suggesting that the cultural exchange was successful. The final result of the translation process and cross-cultural adaptation of the Brazilian version of the painDETECT is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Brazilian version of the painDETECT questionnaire.

Thirty participants with musculoskeletal pain were enrolled in the study. There was a female predominance (73%) with a mean age of 49.73 (±16.14) years old, and the university educational level was the most frequently found (36%). The mean height was 1.68 m (±0.11), and mean weight was 82.60 kg (±18.02). Participants were classified as nociceptive [n = 13 (43%)], probable neuropathic [n = 10 (33%)], and unclear [n = 7 (23%)] in the painDETECT questionnaire.

Reliability

The internal consistency was 0.74 for the nine items, including the pain pattern and the body chart domains. Cronbach’s α of the instrument with seven descriptor items of pain was 0.83.

Discussion

The current study presents the process of a linguistic translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the painDETECT questionnaire for Brazilians, following internationally accepted methodology procedures. All participants of the pretesting phase reported that they understood the items suggesting that the adaptation was successful. Most patients found the painDETECT a clear, readable, well-organized, and useful instrument to assess their pain.

Our results for the reliability were similar to other studies regarding internal consistency. An instrument has good internal consistency when the values of Cronbach’s alpha are between 0.70 and 0.95.10 The original version in German presented an adequate internal consistency (α = 0.76). The current study obtained a Cronbach’s α of 0.74 for the nine items, including the pain pattern and the body chart domains, and a Cronbach’s α of 0.83 for the seven items of symptoms of sensory pain. In other terms, the reliability analysis revealed that the set of items included in the current instrument measures a single construct. The Korean version showed an internal consistency of 0.80,11 while the Turkish version obtained a value of 0.81 for the whole questionnaire, and 0.80 for the Likert items.12 Likewise, the Spanish version attained high values of reliability.13 Thus, the Brazilian version demonstrated adequate internal consistency, corroborating previous studies.

Regarding the limitations of the painDETECT questionnaire, the main one is that the classification probable neuropathic may be insufficient to classify neuropathy.14 However, the painDETECT questionnaire can identify neuropathic-like symptoms,14 and when compared to Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs, the painDETECT questionnaire had higher values of sensitivity and specificity.5 Besides, we did not control the diagnoses, medications, or interventions that participants recruited for the pretesting phase were receiving, which may interfere in pain perception.

Although the painDETECT is a low-cost and simple screening instrument for assessment and identification of symptoms related to neuropathic pain, we acknowledge that the validation procedure for the Brazilian version has not yet been performed. We suggest that future studies carry out the validation process of the now translated and cross-cultural adapted instrument.

Conclusion

The painDETECT was cross-culturally adapted into a Brazilian context and can be used to identify neuropathic components of pain of Brazilian patients. The interpretation of the results of the Brazilian version of the painDETECT must be treated with caution due to the absence of a robust validation methodology of the instrument for Brazilians.

Funding

This study was financed in party by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.06.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bouhassira D., Lantéri-Minet M., Attal N., et al. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Hecke O., Austin S.K., Khan R.A., et al. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. PAIN®. 2014;155:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freynhagen R., Baron R., Gockel U., et al. Pain DETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;2:1911–1920. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colloca L., Ludman T., Bouhassira D., et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:1–19. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiyama A., Katoh H., Sakai D., et al. Clinical impact of JOABPEQ mental health scores in patients with low back pain: analysis using the neuropathic pain screening tool painDETECT. J Orthop Sci. 2017;22:1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freynhagen R., Tölle T.R., Gockel U., et al. The painDETECT project–far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1033–1057. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1157460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attal N., Bouhassira D., Baron R. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain through questionnaires. Lancet Neurol [Internet]. 2018;17:456–466. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Heal. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray C.C.J.L., Abraham J., Ali M.K., et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc [Internet]. 2013;310:591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terwee C.B., Bot S.D.M., de Boer M.R., et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung J.K., Choi J., Jeong J., et al. Korean version of the painDETECT questionnaire: a study for cultural adaptation and validation. Pain Pract. 2017;17:494–504. doi: 10.1111/papr.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkan H., Ardic F., Erdogan C., et al. Turkish version of the paindetect questionnaire in the assessment of neuropathic pain: A validity and reliability study. Pain Med (United States). 2013;14:1933–1943. doi: 10.1111/pme.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Andrés J., Pérez-Cajaraville J., Lopez-Alarcón M.D., et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the painDETECT scale into Spanish. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:243–253. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822bb35b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasvik E., Haugen A.J., Grøvle L. Call for Caution in Using the Pain DETECT Questionnaire for Patient Stratifi cation Without Additional Clinical Assessments: Comment on the Article by Soni et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1201–1202. doi: 10.1002/art.40804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.