Abstract

Background and objectives

Obesity is becoming a frequent condition among obstetric patients. A high body mass index (BMI) has been closely related to a higher difficulty to perform the neuraxial technique and to the failure of epidural analgesia. Our study is aimed at analyzing obese obstetric patients who received neuraxial analgesia for labor at a tertiary hospital and assessing aspects related to the technique and its success.

Methods

Retrospective observational descriptive study during one year. Women with a BMI higher than 30 were identified, and variables related to the difficulty and complications of performing the technique, and to analgesia failure rate were assessed.

Results and conclusions

Out of 3653 patients, 27.4% had their BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-². Neuraxial techniques are difficult to be performed in obese obstetric patients, as showed by the number of puncture attempts (≥ 3 in 9.1% obese versus 5.3% in non-obese being p < 0.001), but the incidence of complications, as hematic puncture (6.6%) and accidental dural puncture (0.7%) seems to be similar in both obese and non-obese patients. The incidence of cesarean section in obese patients was 23.4% (p < 0.001). Thus, an early performance of epidural analgesia turns out to be essential to control labor pain and to avoid a general anesthesia in such high-risk patients.

Keywords: Obesity, Neuraxial anesthesia, Labor analgesia, Cesarean section

Background

Obesity has become an increasi ng concern worldwide and continues to rise in developed countries, both among general and obstetric population. Body mass index (BMI) is nowadays considered a reliable and well-known indicator used worldwide in overweight and obesity diagnosis. Overweight and obesity are defined as a BMI ≥ 25 and ≥ 30 kg.m-², respectively. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity is classified in three categories: obesity grade I (BMI range, 30–34.9 kg.m-²), grade II (range, 35–39.9 kg.m-²), and grade III (> 40 kg.m-²). According to the last data published by the Spanish National Statistics Institute in 2017, 44.3% of men and 30% of women were overweight, and obesity rate was 18.2% in men and 16.7% in women.1 BMI has in fact increased up to 0.4% during the last 30 years worldwide.2 Overweight and obese patients are associated with greater comorbidity, such as coronary diseases, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, or gastrointestinal reflux.2

Obesity during pregnancy is also implicated in the maternal and perinatal outcome. On one hand, obesity is an important risk factor of hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes during pregnancy.3, 4 Hypertension can evolve to preeclampsia, which considerably increases maternal and perinatal morbimortality, and causes intrauterine growth retardation of the fetus. Moreover, a BMI ≥ 25 kg.m-² has been associated to a greater risk of miscarriage (58% versus 37% in non-obese pregnant women) and congenital malformations, mainly spina bifida, neural tube defects, cleft palate and congenital heart diseases.5 A delayed diagnose may be due to the greater difficulty of using ultrasound in these patients. On the other hand, the placenta of obese pregnant women weighs around 60–80 grams more at the time of birth, and it is just placenta weight that has a greater relation to the weight of the newborn.5 Therefore, it seems that fetal macrosomia index, defined as a weight at the time of birth over 4000–4500 grams, is greater among obese women, which justifies a higher odd of cesarean section among these patients.5, 6, 7

The greater rates of instrumental or cesarean delivery in obese pregnant women turns neuraxial anesthesia into the technique of choice. The key is to avoid general anesthesia in patients, whose pregnant condition plus their obesity altogether, increase complications dramatically, such as a difficult airway or failed resuscitation after hemodynamic collapse.4

Therefore, we will discuss the impact of obesity in the obstetric and anesthetic management, as well as focus on the importance of a suitable neuraxial technique on time so as so guarantee the safety of this kind of patient.

Material and methods

Based on the increasing prevalence of obesity among pregnant women and the close relationship between obesity and maternal and perinatal outcomes, we have carried out a retrospective observational descriptive study at a tertiary hospital among pregnant women (obese and non-obese), who received neuraxial analgesia for labor at our center between January and December 2017.

The main purpose was to analyze the features of all pregnant women over 18 years old, as well as different variables in relation to the difficulty of performing the neuraxial technique, and the maternal and neonatal outcomes, so as to be able to establish a comparison with the non-obese obstetric population for the same period. For such reason, we proposed the hypotheses that a high BMI was associated with greater maternal and neonatal comorbidity, a higher difficulty to perform the neuraxial technique and failure rate, as well as a higher cesarean section rate.

Out of the whole sample, women with a BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-² were identified, while variables related to the difficulty of performing the technique, to analgesia failure rate and complications were evaluated. Maternal body mass index was calculated based on the recorded height and weight at delivery. Thus, patients were classified into two groups: non-obese pregnant women (BMI < 30 kg.m-²) and obese pregnant women (BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-²).

Demographic data related to maternal age, to BMI and maternal pathologies, were collected as well as obstetric data (i.e. gestational age, parity, single or twin pregnancy, type of labor (spontaneous or instrumental delivery, and cesarean section), and neonatal data. Information on the technique performed (epidural or combined spinal-epidural) was collected as well. On the bases of the complications of the technique, we defined the success or failure of our technique as the number of puncture attempts, as well as the incidence of hematic puncture (HP) and accidental dural puncture (ADP).

Finally, we identified those cases that required general anesthesia due to a failed neuraxial technique.

Qualitative data description was made in the form of absolute frequencies and percentages. Quantitative data were presented through an average ± typical deviation, minimum and maximum when they were continuous and through the percentile and the interquartile range when dealing with ordinary variables. Qualitative variable association was analyzed by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing qualitative and quantitative data, for independent data, as non-parametric evidence, and the Student's t-student test for independent data as parametric evidence. All statistic tests were considered bilateral and those including p-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant. Data were analyzed by the statistics software SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic data

The study covered a total number of 3653 patients with an average age of 32.82 ± 5.8 years and an average weight of 74.51 ± 12.16 kg (average BMI 27.51 ± 5.75 kg.m-²). Average gestational age was 38.83 ± 2.49 weeks.

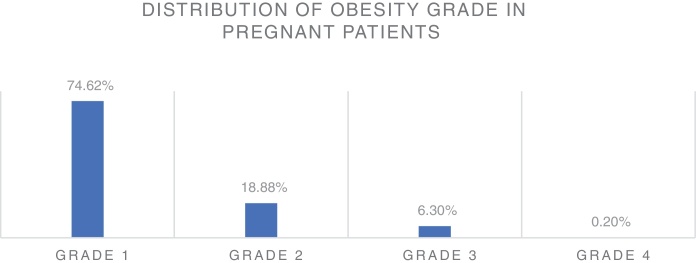

Out of the total number of patients observed (n = 3653), 1001 patients (27,4%) had a BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-² (Fig. 1). According to the BMI, 747 patients (74.62%) had obesity grade I (BMI range, 30–34.99), 189 patients (18.88%) had obesity grade II (BMI range, 35–39.99), 63 patients (6.3%) had obesity grade III or extreme (BMI range, 40–49.99), and 2 patients (0.2%) had obesity grade IV or morbid (BMI 50 or greater).

Figure 1.

Distribution of obesity grade among obese pregnant women.

Obstetric pathology

Gestational Diabetes (GD)

In our study, gestational diabetes rate was slightly higher in obese women (5.2% versus 5% in non-obese), being p = 0.757. Out of the total number of obese pregnant women with GD (n = 51), 39 patients presented obesity grade I (76.5%), 9 patients obesity grade II (17.6%) and 3 patients obesity grade III (5.9%). We did not find any patient among the population studied with obesity grade IV who had GD.

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

In spite of the fact that the incidence of gestational hypertension has turned out to be greater in non-obese (2.3%, n = 60) versus obese (2.1%; n = 20), being p = 0.799, it must be highlighted that there was a greater presence of hypertensive disorders in those pregnant women with obesity grade III (3.3%) versus the other obese patients, with p = 0.882 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hypertensive disorders in obese and non-obese pregnant women (p = 0,799).

| Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy | PATIENT COLLECTION |

|---|---|

| NON-OBESES | 2,3% (n = 60) |

| OBESES | 2,1% (n = 20) |

| Obesity grade I | 2,1% (n = 15) |

| Obesity grade II | 1,6% (n = 3) |

| Obesity grade III | 3,3% (n = 2) |

| Obesity grade IV | 0% |

Neuroaxial technique and complications

It was performed 3237 epidural techniques and 416 combined spinal-epidural (CSE). The technique was required to be repeated in 52 patients out of the total number of obese pregnant women (5.19%) due to the lack of analgesia 45 minutes after the placement of the catheter, and this time, a combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique was performed. One or two puncture attempts were needed in 94.8% of non-obese compared to 90.7% of obese. According to our data, the need of three or more attempts was clearly more frequent among obese, 9.1% against 5.3% of non-obese, being p < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Difficulty of neuraxial technique regarding puncture attempts (p < 0,001).*

| PUNCTURE ATTEMPTS | % OBESE | % NON-OBESES |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 90,8% (n = 883) | 94,8% (n = 2373) |

| 3–4 | 8,3% (n = 81) * | 5,2% (n = 129) * |

| > 4 | 0,8% (n = 8) * | 0,1% (n = 2) * |

These results are statistically significant (p < 0,001).

If all possible complications related to the neuraxial technique are taken into account, the odds of these complications altogether were 72.7% (n = 2021) in the group of non-obese and 27.3% (n = 758) in the obese one. When analyzing each of the complications separately, HP incidence was 6,6% in both groups, being n = 50 among the obese population against n = 133 in non-obese, with p = 0,659, as well as the odds of ADP, which was 0,7% (n = 5) in obese and 0,7% (n = 15) in non-obese with p = 0.659. However, the number of patients who had headache after delivery was higher (8 obese and 37 non-obese women) than the number of ADP recorded in both groups. This can be explained because of the fact that post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is one of the most common postpartum complications following neuraxial block, but dural puncture is not the only cause of postpartum headache. Other possible causes can be tension headache, migraine or cortical vein thrombosis, whose incidence is increased during pregnancy and in the puerperium. A blood patch was performed in only two patients (25%) out of the total obese pregnant women with postpartum headache (n = 8), against 22 out of 37 non-obese pregnant women with postpartum headache (Table 3). In this case, p-value could not be calculated because of the lack of data.

Table 3.

Incidence of postpartum headache and accidental dural puncture (ADP) and the need of blood patch in obese and non-obese parturients.

| OBESE (IMC > 30) | NON-OBESE (IMC < 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| Accidental dural puncture (ADP) | 5/1001 | 15/2652 |

| Postpartum headache | 8/1001 | 37/2652 |

| OBESE (IMC > 30) | NON-OBESE (IMC < 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| BLOOD PATCH | 2 (25%) | 22 (59,45%) |

| NO BLOOD PATCH | 6 (75%) | 15 (40,54%) |

Despite the fact that the number of HP and ADP altogether was greater among non-obese population, when analyzing these complications among the obese population, and depending on the BMI of the patient, we faced in our study a greater incidence in those patients with obesity grade III (16.36%, n = 9), being p = 0.022.

Expulsive phase of labor

Among our studied population, labor was induced in 63.1% (n = 632) of obese versus 26.2% (n = 694) of non-obese. On one hand, delivery was spontaneous in 79% (n = 2096) of non-obese, against 67,6% (n = 677) of obese, where p < 0,001. On the other hand, instrumental delivery was recorded in 9% (n = 90) of obese, contrary to 9.2% (n = 246) of non-obese. Finally, cesarean section rate in obese pregnant women was 23,4% (n = 234), whereas among non-obese was 11.7% (n = 310), being p < 0,001. In our study, the main reason for cesarean section was failure of induction or disproportion between the fetus and the uterus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Delivery in obese and non-obese parturients (p < 0,001).*.

| OBESE (IMC >30) | NON-OBESE (IMC < 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| SPONTANEOUS DELIVERY | 677 (67,6%)* | 2096 (79%)* |

| INSTRUMENTAL DELIVERY | 90 (9%)* | 246 (9,2%)* |

| Spatula | 29 (2,9%) | 91 (3,4%) |

| Forceps | 47 (4,7%) | 101 (3,8%) |

| Ventouse | 14 (1,4%) | 54 (2%) |

| OBESE (IMC >30) | NON-OBESE (IMC < 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| CESAREAN SECTION | 234 (23,4%)* | 310 (11,7%)* |

| - FI or disproportion (NICE III) | 190 (19%) | 234 (8,8%) |

| - NRFS (NICE I) | 44 (4,4%) | 76 (2,9%) |

| NON CESAREAN SECTION | 767 (76,6%)* | 2342 (88,2%)* |

FI (Failed Induction); NRFS (Non-reassuring Fetal Status).

In our population, seven of the patients who underwent a cesarean section required sedation besides the epidural anesthesia due to the lack of pain control. In addition, five women needed general anesthesia because of an incomplete epidural block.

On the bases of our database, the average weight of a newborn child was 3187.26 ± 455.53 grams in non-obese and 3326.67 ± 485.12 grams in obese, being the incidence of fetal macrosomia higher in this latter group (5.6%, n = 51) against 2.6% (n = 64) in non-obese pregnant women, where p < 0.001.

Discussion

Based on our study results, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in obstetric patients is markedly high in our centre, as it has recently become a reference center nationwide for the obstetric follow-up of obese pregnant women. According to test results, obese pregnant women show greater medical comorbidity, which had been widely studied and identified in previous studies. Our findings suggest that the odds of gestational diabetes are slightly higher in the group of obese pregnant women, although statistical significance could not be reached. However, the incidence of hypertensive disorders was 25% (n = 20) in obese against 75% (n = 60) in non-obese. Therefore, although it has not been possible to find a close relation between obese women and hypertensive conditions, it is quite interesting the higher rate of hypertension in obesity grade III. We should be aware that obesity is only one of the multiple risk factors associated with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, such as advanced gestational age or medical conditions (e.g. chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus or chronic renal disease).

In our center, the epidural technique is the first option in any case, but when pregnant women show a breakthrough pain related to strong uterine dynamics or advanced cervical dilatation, then the CSE technique will be preferably performed.

Recent studies show that a high BMI is correlated to4, 5, 7, 8: greater complication to perform the technique, determined as a higher number of puncture attempts and more time needed to find the epidural space; greater failure of epidural analgesia; and greater delay in detecting the failure of the technique.

Despite the fact that a high BMI means a risk factor for the failure of the technique, in our daily practice, we do not observe such a high failure rate in obese pregnant women as the one described in the literature. In our hospital, analgesia for delivery is performed by residents from second up to their last year of training. However, neuraxial techniques in complicated patients (e.g. obese patients or scoliosis) are usually carried out by residents in their last year or the attending anesthesiologist.

In most cases, locating the epidural space in obese pregnant women becomes complicated due to the loss of anatomical references and because the epidural skin-space distance (ESD) may be bigger than usual.4, 8 Previous studies have already recorded the directly proportional association between BMI and ESD, although this distance is not normally longer than 8 cm in most patients.9, 10 Our study did not measure ESD, but has collected a greater number of puncture attempts in obese pregnant women, which confirms a higher difficulty in locating epidural spaces in this type of patient.

Air or saline solution can be used to identify the loss of resistance when finding the epidural space. It is important to highlight that ligaments are softer in obese and pregnant patients due to the influence of progesterone. Based on this, it seems that the feeling of losing resistance using air is more confusing and so the likelihood of false positives increases. Therefore, we can state that the greater the BMI of the patient, the more difficult the puncture becomes, and so the loss of resistance technique with saline solution is recommended for these patients.11 However, we should be aware that epidural space localization using loss of resistance technique with saline can hinder the identification of an ADP (inadvertent dural puncture). When air is used to identify the epidural space, any cerebrospinal leak can be easily recognized, unlike when saline is used. Hence, the ideal technique for identification of the epidural space remains unclear. Moreover, accurate identification of the anatomical references in the obese patient can be widely complicated. The risk of a general anesthesia in such patients is so high, not only because of the pregnancy but also the obesity, that an adequate epidural analgesia must be achieved. Ultrasound (US) techniques are proposed to improve the success rate during epidural catheter insertion, as well as to reduce the complications related to the accidental dural puncture. US imaging of the spine is thought to reduce the likelihood of a failed and traumatic catheterization. Several studies tried to investigate the ease of catheter insertion, the time needed for the procedure and the rate of success, compared to the traditional palpation technique. Some of these studies compared the US examination of the spine in lean and obese patients12 and others analyzed the US guidance only in obese patients scheduled for elective cesarean section13 or otherwise only in patients with BMI < 35 kg.m-².14 Given the results of these studies, US imaging helps locate the epidural space in the obese parturient, and so reduces the number of puncture attempts and the time needed to perform the technique. Nonetheless, the use of US appears not to be that helpful in lean parturients, in which anatomical landmarks are clearly palpable. Thus, there is some evidence that US guidance may improve the success of the neuraxial block in the obese parturient, as well as reduce the rate of procedure-related adverse events. Furthermore, the impact of US on patient satisfaction regarding the technique and analgesia has been highly positive.15 However, the learning curve can be complicated and so US-guided techniques are recommended only when the anesthesiologist is used to perform and interpret US images. In fact, the studies mentioned above have been carried out by experienced anesthesiologists trained in US scanning. In recent years, the use of ultrasonography has become increasingly popular in anesthesiology. Hence, it should be considered in obstetric anesthesia because of its potential benefits in the obese parturient, avoiding a general anesthesia in these patients.

According to the literature, ADP incidence in the obstetric population is up to 4% in obese pregnant women versus 1% in non-obese ones.16, 17, 18 In our study, complications such as ADP or HP seem to be similar in both groups, although we have not been able to demonstrate that such associations are statistically significant. When all complications related to the neuraxial technique are considered, the rate of these complications in the obese patient is not higher comparing to non-obese in our study. As previously mentioned, the technique in the obese parturient has been performed by experienced anesthesiologists, so the probability of success was higher in such patients. Around 50-80% of patients with ADP develop PDPH.19, 20, 21, 22 Our study has not found a higher PDPH incidence among obese population, which matches the results obtained in previous studies. In fact, the Peralta et al. study16 demonstrated that a BMI ≥ 35 kg.m-² was a protective factor against the development of PDPH. The reason is related to a higher pressure in the epidural space, which limits the leak of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) just through the dural rent. Nonetheless, once PDPH has developed, its severity and treatment (analgesia and/or blood patch) do not seem to be related to the BMI of the patient.

As there is not still a standard definition of failure of the epidural technique, it appears to be difficult to report its real incidence. A widely acceptable definition is the lack of analgesia during the first 45 minutes after placing the catheter in the epidural space.8 Kula et al., in their study,4 mentioned the assessment of the number of necessary attempts to place a catheter as the way to estimate how difficult the technique was and the likelihood of failure. Saravanakumar et al. found in their study that 74% of pregnant women needed more than one attempt, and up to 14% required three or more attempts, being the total failure rate for this technique 42% in this kind of patient.23 In our study, we have been able to assess the success of the technique according to the number of puncture attempts and we did identify a correlation with data obtained in the literature.

Finally, we noted a higher rate of cesarean delivery in obese pregnant women. The literature states a greater anesthetic risk among obese women who undergo cesarean section under general anesthesia, as it is expected due to the physiological and anatomical changes during pregnancy. In this sense, Brick et al. do mention a higher cesarean delivery rate among obese multiparous pregnant women, while such relation between BMI and the likelihood of cesarean section is not found in obese nulliparous pregnant women.24

Eventually, we observed in our population significant statistics when referring to a greater incidence of fetal macrosomia in obese pregnant women, which is in line with the latest breakthroughs in the literature. This can be related to a greater concentration of leptin and interleukin-6 (IL6) in the umbilical cord of babies delivered by obese mothers, which seems to be in relation to a higher resistance to insulin and long-term metabolic disorders among these newborn children, according to Catalano and Shankar studies.5

To sum up, neuraxial techniques are preferred for obese parturient, in who the placement of a well-functioning epidural catheter is one of the safest methods of providing labor analgesia. It must be taken into account that labor epidural analgesia can be converted to surgical anesthesia if needed for cesarean delivery and, given the increased risk of fetal macrosomia, a well-functioning epidural catheter can be helpful in the management of a shoulder dystocia. Therefore, regular assessment of the labor epidural catheter is paramount to ensure that the block can be reliably extended to provide adequate surgical anesthesia if needed.23, 25, 26

Our results should be interpreted in the context of study’s limitations:

-

-

As it is a retrospective study, information has not been collected systematically, and the lack of data makes it difficult to find statistically relevant relations in some cases, in spite of being in line with what is described in the literature.

-

-

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, maternal BMI was calculated based on the recorded weight and height in the third trimester of pregnancy. As we did not have previous data, the accurate weight before pregnancy could not be recorded. This makes us consider obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-²) those pregnant women who may be not before pregnancy.

Conclusion

Our study is aimed at analyzing obese obstetric patients who received neuraxial analgesia for labor at a tertiary hospital and assessing aspects related to the technique and its success. Given the number of puncture attempts, our findings suggest evidence of greater difficulty in performing neuraxial anesthesia in obese pregnant women. However, it seems that complications related to neuraxial blockade are similar in both groups although statistical significance could not be reached. Lastly, it must be noted the higher incidence of cesarean section and macrosomia among the obese pregnant women.

Due to the increasing incidence of obesity in general and obstetric population, the anesthesiologist must be ready to deal with any potential complications that may develop at delivery. These parturients remain challenging for obstetric and anesthesia providers. Thus, the experience of the anesthesiologist with this kind of patients becomes a pivotal point to achieve a satisfactory neuraxial analgesia and an adequate management of the obese pregnant woman. Early epidural anesthesia in these patients is the best option to guarantee an appropriate analgesia and avoid a general anesthesia. Given their pregnancy and obesity, these patients are therefore considered to be at high anesthetic risk. It is thus crucial to closely watch over these patients from the moment of inserting the epidural catheter until labor.

Summing up, given the high prevalence of obese pregnant women in the last years, a multidisciplinary approach to this profile of patient turns out to be necessary, including anesthesiologists and obstetricians, in order to reduce such complications and warrant an adequate analgesia in the obese pregnant women.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

CEIm approval (Comité de Etica de la Investigación con medicamentos del Hospital Universitario La Paz). Project number: PI-3730

References

- 1.Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Índice de masa corporal según grupos de edad (% población de 18 y más años), recuperado de: http://www.ine.es.

- 2.Riveros-Perez E., McClendon J., Xiong J., et al. Anesthetic and obstetric outcomes in pregnant women undergoing cesarean delivery according to body mass index: Retrospective analysis of a single-center experience. Ann Med Surg. 2018;36:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan E.A., Dickinson J.E., Vaughan G.A., et al. and on behalf of the Australasian Maternity Outcomes Surveillance System (AMOSS) – Maternal super-obesity and perinatal postcomes in Australia: a national population-based cohort study. Sullivan et al. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:322. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kula A.O., Riess M.L., Ellinas E.H. Increasing body mass index predicts increasing difficulty, failure rate, and time to discovery of failure of epidural anesthesia in laboring patients. J Clin Anesth. 2017;37:154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catalano P.M., Shankar K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ. 2017;360:j1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane J.M.G., Murphy P., Burrage L., et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of extreme obesity in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:606–611. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30879-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonidandel A., Booth J., D’Angelo R., et al. Anesthetic and Obstetric outcomes in morbidly obese parturients: a 20-year follow-up retrospective cohort study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2014;23:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guasch E., Iannuccelli F., Brogly N., et al. Failed epidural for labor: what now? Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83:1207–1213. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.17.12082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guasch E., Ortega R., Gilsanz F. Analgesia epidural para parto en la gestante obesa. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2006;13:468–474. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eley V.A., Chin A., Sekar R., et al. Increasing body mass index and abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness are associated with increased skin-to-epidural space distance in pregnant women. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;38:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinoza-Hernández C.Y., Estrada-Utrera M.S., Islas-Ruíz F.G., et al. Técnica de Nesi para identificación del espacio epidural vs técnica de Pitkin en cirugía obstétrica. Anest Méx. 2016;28:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahin T., Balaban O., Sahin L., et al. A randomized controlled trial of preinsertion ultrasound guiadance for spinal anesthesia in pregnancy: Outcomes among obese and lean parturients: Ultrasound for spinal anesthesia in pregnancy. J Anesth. 2014;28:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s00540-013-1726-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M., Ni X., Xu Z., et al. Ultrasound-assisted technology versus the conventional landmark location method in spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery in obese parturients: A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Anal. 2019;129:155–161. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tawfik M.M., Atallah M.M., Elkharboutly W.S., et al. Does preprocedural ultrasound increase the first-pass success rate of epidural catheterization before cesarean delivery? A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:851–856. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gredilla E., Pérez Ferrer A., Canser E., et al. Factores asociados a la satisfacción materna con analgesia epidural para control del dolor del trabajo de parto. Med Prevén. 2008;14:22–27. doi: 10.1016/s0034-9356(08)70534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peralta F., Higgins N., Lange E., et al. The relationship of body mass index with the incidence of postdural puncture headache in parturients. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:451–456. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miu M., Paech M.J., Nathan E. The relationship between body mass index and post-dural puncture headache in obstetric patients. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2014;23:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An X., Zhao Y., Zhang Y., et al. Risk assessment of morbidly obese parturient in cesarean section delivery. A prospective cohort, single-center study. Medicine. 2017;96:42. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López Correa T., Garzón Sánchez J.C., Sánchez Montero F.J., et al. Cefalea postpunción dural en obstetricia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2011;58:563–573. doi: 10.1016/s0034-9356(11)70141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anne MacGregor E. Headache in pregnancy. Neurol Clinics. 2012;30:835–866. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franz A.M., Jia S.Y., Bahnson H.T., et al. The effect of second-stage pushing and body mass index on postdural puncture headache. J Clin Anesth. 2017;37:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song J., Zhang T., Choy A., et al. Impact of obesity on postdural puncture headache. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2017;30:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saravanakumar K., Rao S.G., Cooper G.M. Obesity and obstetric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:36–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brick A., Layte R., McKeating A., et al. Does maternal obesity explain trends in caesarean section rates? Evidence from a large Irish maternity hospital. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;189:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s11845-019-02095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor C.R., Dominguez J.E., Habib A.S. Obesity and Obstetric Anesthesia: current insights. Local Reg Anesth. 2019;12:111–124. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S186530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall S.J., Li Z., Kurinczuk J.J., et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with BMI & 50: An international collaborative study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]