Abstract

Herein it is reported how the overlap concentration (C*) can be used to overcome crosslinking due to diol impurities in commercial PEG, allowing for the synthesize of bottlebrush polymers with good control over molecular weight. Additionally, PEG-based bottlebrush networks are synthesized via ROMP, attaining high conversions with minimal sol fractions (<2%). The crystallinity and mechanical properties of these networks are then further altered by solvent swelling with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate/DCM cosolvents. The syntheses reported here highlight the potential of the bottlebrush network architecture for use in the rational design of new materials.

Keywords: overlap concentration, romp, bottlebrush, network, peg, ionic liquid, swelling

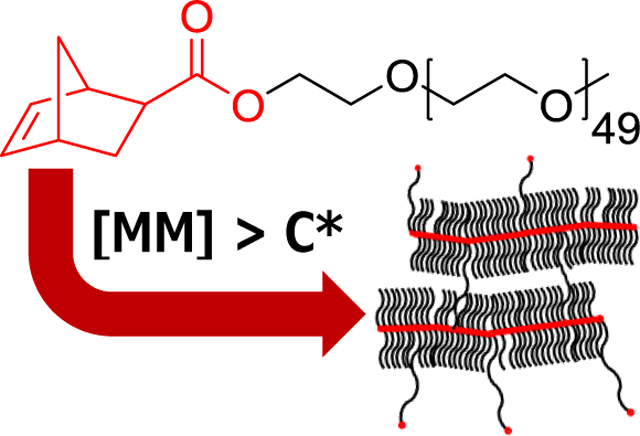

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Bottlebrush polymers are materials composed of polymeric backbones densely-grafted with side chains, where the high concentration of side chains forces the backbone of the polymer to expand due to steric repulsion.1 This unique architecture has recently gained attention for their potential applications in lubrication, anti-fouling, nanowires, templating, florescent tags, and elastomers.1–7 Bottlebrushes are typically prepared by one of three methods: (1) the grafting-through strategy, where side chains are polymerized together into a brush, (2) the grafting-from strategy, where side chains are grown from a backbone, and (3) the grafting-to strategy, where pre-synthesized chains are attached to the backbone.1,8,17,18,9–16 A variety of bottlebrush polymers have been reported within the literature, synthesized predominately with PDMS, PS, PnBA, PLA, and PEG side chains.1,8,9,19–21

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based materials have also received much attention due to their spectrum of unique properties ranging from water solubility and biocompatibility to ionic-conductivity.22–31 Recently, many studies where PEG was introduced into soluble block copolymers, blends, and bottlebrushes have appeared, resulting in materials sporting altered crystallinity, morphologies, and mechanical properties.32,33,42,34–41 Specifically, research detailing the adoption of PEG-side chains into bottlebrush polymers has led to a variety of novel materials with applications spanning from water-soluble molecules to tunable ion-conductive materials.43–51

An emerging area of research is the design of networks where the chains between crosslinks emulate the bottlebrush architecture.1,2,52–54 These bottlebrush networks feature numerous architectural parameters including side chain length (nsc) degree of polymerization between crosslinks (nx), grafting density (ng), and the chemistry of macromonomers.2,52 This diversity of parameters provides an opportunity for the rational design of network materials, offering greater control over structure than conventional networks. While this bottlebrush network architecture has been applied extensively to the development of elastomeric materials, it has been extended only sparingly to PEG homopolymer materials, where PEG bottlebrush networks remain understudied.55

Herein we modify the architecture of PEG materials by polymerizing bottlebrush networks from PEG-based macromonomers. Aiming for high, quantitative conversion, bottlebrush networks are prepared using ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP), utilizing a grafting-through strategy with PEG macromonomers end-functionalized with norbornene. The effectiveness of our chemistry is evaluated by synthesizing a series of PEG bottlebrush polymer controls, using the overlap concentration (C*) as a guide to avoid gelation. We further alter the conditions of networks via solvent swelling with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate ([EMIM][EtSO4]) to produce a PBS swollen network and an ionogel respectively. Networks were swollen in an ionic liquid due to (1) their low vapor pressure, (2) low flammability, and (3) potential for use in extraction, catalysis, and rapid drug delivery.56 We show that polymerizing PEG macromonomers into bottlebrush networks results in decreased crystallinity, with further swelling influencing mechanical properties.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Macromonomer Synthesis

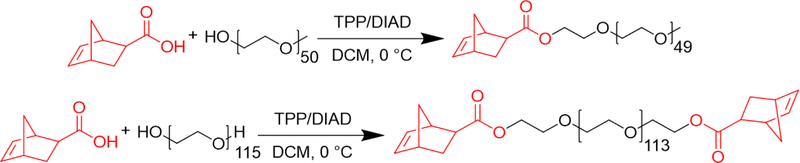

Macromonomers were synthesized using the Mitsunobu reaction to end-functionalize mono- and di-functional PEG chains with norbornene (Scheme 1).57,58 The monofunctional macromonomer will hereafter be referred to as the ‘PEG macromonomer’, while the difunctional macromonomer will be referred to as the ‘crosslinker’. Norbornene carboxylic acid was chosen over the imide and anhydride variants because (1) it is commercially available, (2) there is no need to thermally rearrange to the exo-stereoisomer for optimal reactivity, and (3) there are half as many carbonyl groups for the ruthenium catalyst to chelate to during the polymerization process, resulting in a more favorable reaction.59–62

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of (top) the PEG macromonomer and (bottom) the difunctional PEG crosslinker via the Mitsunobu reaction. GPC and 1H-NMR spectra in Figures S1–4.

2.2. Bottlebrush Polymer Synthesis

A series of linear bottlebrush polymers were synthesized as controls to ascertain the effectiveness of ROMP with the PEG macromonomer. Reactions were carried out at room temperature in dichloromethane (DCM) using Grubbs’ 2nd Generation Catalyst. The initial series of bottlebrush polymers were synthesized at 0.125 g/mL of PEG macromonomer with no crosslinker added to the reaction mixture to mimic the conditions of the network polymerizations in Section 2.3. Unsurprisingly, polymerization under these conditions resulted in insoluble gels due to the presence of a commonly known diol impurity in commercial PEG.8,63–65 This impurity was small enough in our macromonomer to have no effect on peak integration ratios in its 1H-NMR spectra, indicating its presence in low amounts (much lower than the 8% reported elsewhere).65

While this diol impurity is known to exist in commercial PEG materials, to our knowledge there are no instances of directly addressing this issue as it pertains to bottlebrush synthesis. A common impurity amongst materials polymerized anionically, diol contaminants have been historically difficult to visualize, and challenging to remove due to having a polarity similar to that of their monofunctional counterparts.66–69 This issue can be avoided by either polymerizing PEG under more stringent conditions or by carrying out reactions under extremely dilute conditions, ostensibly avoiding gelation.

By modelling these macromonomers as freely jointed PEG chains with Mw=2080, the overlap concentration (C*) was determined to be descriptive of the transition between bottlebrush polymers and gels. We began by calculating the mean square end-to-end distance of the PEG chains (<R2>) using Equation (1)70:

| (1) |

where N = 52 is the number of segments and b = 0.72 nm is the segment length of a PEG monomer.71 This <R2> was then used to calculate C* using Equation (2)70:

| (2) |

where ρ = 1.064 g/mL is the monomer density, vmon = 0.069 nm3 is the monomer volume, and V = R3 = 139.96 nm3 is the pervaded volume of the polymer chain.70

Solutions of macromonomer were polymerized at concentrations above and below C* with constant monomer to initator ratios (M:I = 1000) and reaction volumes (2 mL) with no crosslinker added to the reaction. In this way, we show that by staying below the C* of our macromonomer it is possible to polymerize bottlebrush polymers, while concentrations above C* result in gelation (Figure 1). 1H-NMR data describing the quantitative conversion of the reaction is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

At 11.9 nM the reaction mixture is below the overlap concentration (C*) of the macromonomer chains, leading to no gelation. At 13.2 nM, the reaction mixture is above the C* of macromonomer chains, resulting in gelation. The experimental onset of gelation at 13.2 nM is nearly equivalent to the C* of a freely jointed PEG chain, where C* = 13.1 nM.

Figure 2.

1H-NMR spectra of (black) unreacted macromonomer and (red) a PEG bottlebrush polymer with an M:I of 10 in DCM. The disappearance of the macromonomer’s ‘ene’ protons (orange dots) and subsequent appearance of the bottlebrush’s backbone ‘ene’ protons (green dots) provide evidence that the polymerization achieved quantitative conversion. Full 1H-NMR spectra of bottlebrush polymer available in Figure S5.

Using size exclusion chromatography multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) we show that by staying below C* it is possible to produce bottlebrushes of different Mws with good control over molecular weight, regardless of the diol impurity (Figure 3). It is notable that the Đ of the bottlebrushes decreases as the molecular weight of the polymer increases (1.4 at M:I = 10 as opposed to 1.1 at M:I = 1000). In all cases, GPC peaks are near-monomodal with a decrease in Mw across the peak, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3:

(top) SEC data of M:I = 1000 sample with the molar mass obtained from MALS plotted along it. (bottom) Table of information obtained via THF-GPC and SEC-MALS. The Mw was obtained from a dn/dc value previously used in the literature (0.18).21 The dispersity of the samples Đ was obtained using THF-GPC and used to calculate Mn. The DP of each sample was calculated from Mn using a repeat molecular weight of 2100 g/mol. Full THF-GPC spectra available in Figures S6–9.

2.3. Bottlebrush Network Synthesis

Following the successful preparation of our bottlebrush polymer controls, a series of PEG bottlebrush networks were synthesized by adding crosslinker to the reaction (Scheme 2). These networks were all polymerized with 5 mol% crosslinker and Mw = 2100 g/mol PEG side chains, corresponding to nx = 10 and nsc = 50. All gels were polymerized in vials overnight at room temperature, with the resulting gels being quenched with ethyl vinyl ether (EVE). To obtain gel fraction data, the gels were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 hours to remove excess solvent before being massed. The gel fractions of all resulting networks were consistently >0.98 after 3 washes with DCM. Heating the networks allowed for them to be annealed into transparent, flat discs, with a thickness of 2 mm and a diameter of 12 mm (Figure 4(a–b)).

Scheme 2.

PEG bottlebrush network prepared via ROMP using Grubbs’ 2nd Generation catalyst (G2) at room temperature in DCM. The reaction took place overnight and was quenched with ethyl vinyl ether (EVE).

Figure 4.

PEG bottlebrush networks (a) unswollen at room temperature, (b) unswollen at 60 °C, (c) swollen with PBS, (d) swollen with [EMIM][EtSO4]/DCM cosolvent, and (e) swollen with [EMIM][EtSO4]. The Q-values for each of the swollen networks is stated under each swollen sample. The unswollen network was heated to 60 °C in order to melt the PEG side chains, allowing the sample to become more transparent. The ionogel (e) was obtained by evaporating off the DCM in the cosolvent swollen gels (d). While the PBS and [EMIM][EtSO4]/DCM swollen networks have nearly doubled in diameter from the unswollen state, the [EMIM][EtSO4] loaded sample has largely maintained its original diameter and opaqueness.

2.4. Bottlebrush Network Swelling

Following synthesis, these networks were swollen in a variety of solvents including DCM, water, phosphate buffer solution (PBS), and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate ([EMIM][EtSO4] or IL) (Figure 4c–e). PBS was used as an alternative to water, as the networks fractured during swelling in water. When using PBS as a solvent, the networks swelled to a ratio of Q = 13.1. After 72 hours in 5 mL of IL, no mass increase was observed in “swollen” networks. To facilitate the uptake of IL into the networks, a DCM cosolvent was adopted. DCM was chosen as a cosolvent due to its miscibility with [EMIM][EtSO4] and its relatively high swelling ratio (Q = 19.6). Various cosolvent mixtures of IL/DCM were examined to achieve a range of IL swelling ratios (Figure 5). Larger swelling ratios of [EMIM][EtSO4] were obtained by increasing the amount of DCM in the cosolvent rather than increasing the amount of [EMIM][EtSO4], with a linear relationship observed in Figure 5. This indicates that the primary factor determining Q of [EMIM][EtSO4] in the network is the overall degree of swelling in our IL/DCM cosolvent, and not the actual amount of IL used.

Figure 5.

Cosolvent swollen networks were produced from varying cosolvent compositions of [EMIM][EtSO4]/DCM.The [EMIM][EtSO4] swollen networks were obtained by evaporating the DCM from cosolvent swollen networks. There is a clear linear relationship between cosolvent swelling ratio and [EMIM][EtSO4] swelling ratio, where higher amounts of [EMIM][EtSO4] in the cosolvent correspond to lower swelling ratios. Q values plotted against % volume of [EMIM][EtSO4] in cosolvent available in Figure S10.

2.5. Young’s Modulus via Indentation

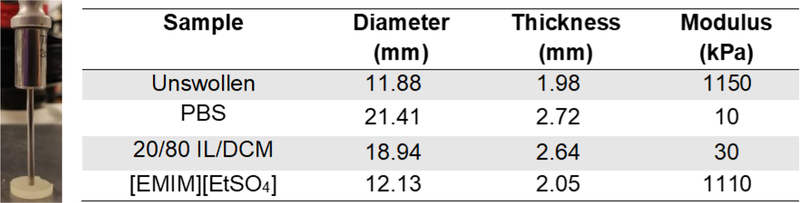

Using the procedure and equations described by Shull and coworkers, the Young’s modulus (E) of the swollen and unswollen PEG bottlebrush networks were measured via indentation (Figure 6).72 While the bottlebrush networks swollen in PBS and IL/DCM cosolvent were markedly softer than their unswollen state, the IL swollen network is similar in modulus, despite containing enough IL to constitute half of the sample’s mass.

Figure 6.

(Left) Indentation being performed on a PEG network using a texture analyzer. (Right) A compilation of the geometry and moduli of each of the networks. Measurements of samples were performed using calipers, while the Young’s Modulus (E) was determined via analysis of indentation data.

2.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

We utilize DSC to examine how changes in the crystallinity of our materials correspond to variation in modulus values (Table 1). From these measurements, it is apparent that the crystallinity of our materials can be decreased by (1) polymerizing PEG macromonomers into bottlebrushes, (2) polymerizing PEG macromonomers and crosslinker into bottlebrush networks, and (3) swelling those networks with solvent. Among these alterations, two are particularly notable: the PBS swollen network, where the crystallinity has completely disappeared and the modulus has sharply declined, and the IL swollen network, where the crystallinity of the material is slightly reduced, but the modulus of the material is essentially unaltered. The increase in ΔHc observed between the PEG bottlebrush polymer and the unswollen network is likely a result of the additional PEG crosslinker added to the system.

Table 1.

ΔHc and E values for various PEG materials. All networks were polymerized with M:I = 1000.

| Sample | ΔHc (J/g) | Modulus (kPa) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 2k PEG | 130 | N/A |

| Macromonomer | 135 | N/A |

| DP 1000 Brush | 88 | N/A |

| Unswollen | 114 | 1150 |

| PBS | 0 | 10 |

| [EMIM][EtSO4] | 96 | 1110 |

2.7. Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA)

The unswollen network, the PBS swollen network, and the 20% IL swollen network were further examined using DMTA to determine the frequency dependence of their storage and loss moduli (Figure 7). At room temperature the unswollen PEG network has a storage modulus on the order of 103 kPa, a value in agreement with that determined through indentation (Figure 7a). The storage and loss moduli are frequency independent for the entire range examined, in a manner consistent with the dynamics of a nearly perfect network.70 When heated above the melting point of PEG, the unswollen network moduli decrease by ~2 orders of magnitude, with the loss modulus becoming frequency dependent in a manner consistent with other bottlebrush networks in the literature (Figure 7b).2,54,73

Figure 7.

DMTA data acquired from (a) unswollen PEG bottlebrush network at room temperature, (b) unswollen PEG bottlebrush network at 60 °C, where the side chains have melted, (c) 20% IL swollen PEG bottlebrush network, and (d) a PBS swollen bottlebrush PEG network at room temperature. Notably, the unswollen and IL swollen samples have nearly identical moduli, despite the level of [EMIM][EtSO4] retained in the network. The heated sample displays moduli behavior characteristic of existing bottlebrush networks, with a frequency independent storage modulus and a frequency dependent loss modulus over higher frequencies. In the PBS swollen sample, the storage modulus has a frequency dependence in the high frequency regime, while the loss modulus becomes frequency dependent in the low frequency regime.

Interestingly, although consisting of nearly 50% IL by mass, the storage and loss moduli of the 20% IL swollen bottlebrush network appear identical to those of the unswollen bottlebrush network (Figure 7a/7c). In stark contrast to this, the moduli of the PBS swollen bottlebrush network are considerably lower than those of the unswollen bottlebrush network at room temperature, with storage modulus values on the order of 101-102 kPa (Figure 7d). These storage modulus values are also in agreement with the indentation data discussed previously (Figure 6). The loss modulus has also declined noticeably, from ~200 kPa in the unswollen bottlebrush network to ~1 kPa in the PBS swollen bottlebrush network.

3. Conclusion

PEG macromonomers were synthesized and subsequentially polymerized via ROMP. The C* of PEG was shown to serve as a good predictor of when the known diol impurity in the macromonomer would prevent soluble bottlebrushes from being polymerized, with concentrations above C* resulting in gelation. A series of PEG bottlebrush polymers and PEG bottlebrush networks were then polymerized and characterized using C* as a guideline. These PEG bottlebrush polymers and bottlebrush networks have lower ΔHc values than the starting PEG material, with the reduction in crystallinity accompanied by lowered modulus values. Further solvent swelling also effected the mechanical properties of the PEG bottlebrush networks, dramatically in the case of the PBS swollen network and minor in the case of the [EMIM][EtSO4] swollen network. Through DMTA, we show how melting the PEG side chains results in the appearance of a frequency dependent loss modulus in the high frequency regime, a feature characteristic of bottlebrush networks in the literature. The syntheses reported here highlight the potential of the bottlebrush network architecture for use in the rational design of new materials.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Fisher, Sigma Aldrich, and Tokyo Chemical Institute. The [EMIM][EtSO4] was received as a gift from Professor David Hoagland. All chemicals were used as received unless otherwise noted.

4.2. Synthesis of mono-functionalized PEG macromonomer

Norbornene-functionalized PEG was synthesized via the Mitsunobu reaction. PEG (6.995 g, 3.50 mmol) was placed in a dry round bottom flask with a stir bar and dried overnight in a vacuum oven. The dried PEG was dissolved in 30 mL of dried DCM and placed under N2 before adding exo-5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid (0.967 g, 7.00 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (TPP; 1.836 g, 7.00 mmol) to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was chilled in an ice water bath for fifteen minutes before adding diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD; 1.375 mL, 7.00 mmol) dropwise to the reaction mixture. Reaction was allowed to run overnight before being concentrated and precipitated/washed in cold diethyl ether. Product was a white powder obtained at a yield of 92%. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 6.16–6.09 (m, 2H), 4.265–4.225 (t, 2H), 3.90–3.45 (m, 188H), 3.43–3.35 (s, 3H), 3.08–3.00 (s, 1H), 2.98–2.87 (s, 1H), 2.30–2.23 (q, 1H), 2.00–1.90 (s, 1H), 1.56–1.20 (m, 2H) (Figure S1).

4.3. Synthesis of di-functionalized PEG crosslinker

Norbornene end-functionalized PEG crosslinker was synthesized via the Mitsunobu reaction in a manner identical to the mono-functionalized PEG. To dried PEG (4.523 g, 0.983 mmol), exo-5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid (0.815 g, 5.898 mmol) and TPP (1.547 g, 5.898 mmol) were added under N2. DIAD (1.506 mL, 5.898 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 6.16–6.09 (m, 4H), 4.265–4.225 (t, 4H), 3.90–3.45 (m, 469H), 3.08–3.00 (s, 2H), 2.98–2.87 (s, 2H), 2.30–2.23 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.90 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.20 (m, 6H) (Figure S2).

4.4. Bottlebrush Synthesis

Monofunctional PEG (0.25 g, 0.119 mmol) was dried in a round bottom flask overnight with a stir bar in a vacuum oven. Bottlebrush polymers were synthesized with varied macromonomer/initiator ratios using Grubbs’ 2nd Generation catalyst (0.101 mg, 0.119 μmol) in 15 mL dried DCM under N2. The reactions were run overnight and quenched with a few drops of ethyl vinyl ether. Brushes were precipitated in cold diethyl ether and collected as a fluffy white solid. GPC of brushes available in SI (Figures S6–9).

4.5. Bottlebrush Network Synthesis

Monofunctional PEG (0.25 g, 0.119 mmol) and difunctional PEG (27.38 mg, 5.95 μmol) were placed in a 20 mL vial in 1 mL of dried DCM. 1 mL of Grubbs’ 2nd Generation catalyst (M:I = 1000; 0.101 mg, 0.119 μmol) in dried DCM was added to the vial and allowed to react overnight before being quenched with a few drops of ethyl vinyl ether. Networks were dried, washed 3 times in DCM, and dried again to obtain gel fraction data using Equation 3:

| (3) |

with f values obtained being >98% for all networks polymerized. Networks were subsequently swollen in various solvents to obtain the swelling ratios for those solvents using Equation 4:

| (4) |

4.6. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) and Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS).

Standard GPC was performed using a Polymer Laboratories PL- GPC50 instrument with two 5 μm mixed-D columns, a 5 μm guard column, and a RI detector (HP1047A); THF was used as the eluent with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min; polystyrene standards were used for the calibration. SEC MALS was performed in THF + 1 vol % TEA using two Polymer Laboratories 10 μm mixed-B LS columns connected in series with a Wyatt Technologies DAWN EOS MALLS detector and RI detector at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. No calibration standards were used as dn/dc was known and 100% mass elution was assumed. The dispersity (Đ) of each bottlebrush polymerization was measured by SEC, which was performed using dried THF as the eluent. MALS was used to determine the Mw of synthesized brushes, with an eluent of THF and 1% triethylamine.

4.7. Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR)

1H-NMR was used to determine successful synthesis of (1) the monofunctional PEG, (2) the difunctional PEG and (3) quantitative conversion of the M:I = 10 bottlebrush polymer. 1H-NMR spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker Advance 500 MHz NMR spectrometer with CDCl3 as a solvent.

4.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The ΔHc values were determined by integrating under the area of the curve obtained during the cooling step of a heat-cool-heat cycle. The thermal history of the sample was removed by increasing the temperature of the sample from 21 °C to 120 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The heating rate during the cooling step was set to 2 °C/min, where it was decreased to −20 °C and heated again to 60 °C at 2 °C/min. Measurements were taken using a DSC Q200 from TA Instruments.

4.9. Indentation with a Texture Analyzer

Networks were indented with a 2 mm probe at a loading rate of 0.01 mm/sec to a force of 20 mN, whereupon the probe retracted at an unloading rate of 0.01 mm/sec. The probe was cleaned with acetone between runs. Force/displacement data was analyzed using Equation 572:

| (5) |

where E is Young’s Modulus, P is the load applied, α is the radius of the indentation probe, δ is the displacement of the probe, and h is the thickness of the sample. Force/displacement data were collected using a TA.XT Plus Texture Analyzer from Texture Technologies.

4.10. Dynamic Mechanical Thermal Analysis (DMTA)

Networks were cut into 8 mm circles with a circular punch and placed within the compression clamps of a Discovery DMA 850 from TA Instruments, equipped with a thermal stage. The samples were run either at 21 °C or at 60 °C, sweeping a frequency range of 0.1–100 Hz at a strain rate of 1%. The sample stage was cleaned with isopropyl alcohol between samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Graduate Assistance in Areas of Need (GAANN) Fellowship, the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Research Service Award T32 GM135096, and the Army Research Lab’s (ARL) National Center for Manufacturing Science (NCMS) Award ID# HQ00341520007. Facilities used during the conducting of this research are maintained by the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- (1).Xie G; Martinez MR; Olszewski M; Sheiko SS; Matyjaszewski K Molecular Bottlebrushes as Novel Materials. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20 (1), 27–54. 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Daniel WFM; Burdyńska J; Vatankhah-Varnoosfaderani M; Matyjaszewski K; Paturej J; Rubinstein M; Dobrynin AV; Sheiko SS Solvent-Free, Supersoft and Superelastic Bottlebrush Melts and Networks. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15 (2), 183–189. 10.1038/nmat4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Xiao L; Li J; Peng G; Huang G The Effect of Grafting Density and Side Chain Length on the Conformation of PEG Grafted Bottlebrush Polymers. React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 156 (August), 104736. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wu D; Nese A; Pietrasik J; Liang Y; He H; Kruk M; Huang L; Kowalewski T; Matyjaszewski K Preparation of Polymeric Nanoscale Networks from Cylindrical Molecular Bottlebrushes. ACS Nano 2012, 6 (7), 6208–6214. 10.1021/nn302096d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Walsh DJ; Dutta S; Sing CE; Guironnet D Engineering of Molecular Geometry in Bottlebrush Polymers. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (13), 4847–4857. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Li Z; Tang M; Liang S; Zhang M; Biesold GM; He Y; Hao SM; Choi W; Liu Y; Peng J; et al. Bottlebrush Polymers: From Controlled Synthesis, Self-Assembly, Properties to Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 116, 101387. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2021.101387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Williams-Rice M “Bottlebrush” polymers bring coatings under control - Futurity https://www.futurity.org/bottlebrush-polymers-coatings-2212702/ (accessed Nov 1, 2020).

- (8).Choinopoulos I Grubbs’ and Schrock’s Catalysts, Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization and Molecular Brushes-Synthesis, Characterization, Properties and Applications. Polymers (Basel). 2019, 11 (2), 1–31. 10.3390/polym11020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Leitgeb A; Wappel J; Slugovc C The ROMP Toolbox Upgraded. Polymer (Guildf). 2010, 51 (14), 2927–2946. 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Nikovia C; Theodoridis L; Alexandris S; Bilalis P; Hadjichristidis N; Floudas G; Pitsikalis M Macromolecular Brushes by Combination of Ring-Opening and Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Synthesis, Self-Assembly, Thermodynamics, and Dynamics. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (21), 8940–8955. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhou L; Zhang K; Ma J; Cheng C; Wooley KL Facile Syntheses of Cylindrical Molecular Brushes by a Sequential RAFT and ROMP “Grafting-through” Methodology. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 5557–5563. 10.1002/pola. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Xia Y; Kornfield JA; Grubbs RH Efficient Synthesis of Narrowly Dispersed Brush Polymers via Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Macromonomers. Macromolecules 2009, 42 (11), 3761–3766. 10.1021/ma900280c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gao H; Matyjaszewski K Synthesis of Molecular Brushes by “Grafting onto” Method: Combination of ATRP and Click Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (20), 6633–6639. 10.1021/ja0711617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Johnson JA; Lu YY; Burts AO; Xia Y; Durrell AC; Tirrell DA; Grubbs RH Drug-Loaded, Bivalent-Bottle-Brush Polymers by Graft-through ROMP. Macromolecules 2010, 43 (24), 10326–10335. 10.1021/ma1021506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Matyjaszewski K Synthesis of Amphiphilic Poly( N -Vinylpyrrolidone)- b -Poly(Vinyl Acetate) Molecular Bottlebrushes. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Neugebauer D; Zhang Y; Pakula T; Sheiko SS; Matyjaszewski K Densely-Grafted and Double-Grafted PEO Brushes via ATRP. A Route to Soft Elastomers. Macromolecules 2003, 36 (18), 6746–6755. 10.1021/ma0345347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hong SW; Gu W; Huh J; Sveinbjornsson BR; Jeong G; Grubbs RH; Russell TP On the Self-Assembly of Brush Block Copolymers in Thin Films. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (11), 9684–9692. 10.1021/nn402639g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gu W; Huh J; Hong SW; Sveinbjornsson BR; Park C; Grubbs RH; Russell TP Self-Assembly of Symmetric Brush Diblock Copolymers. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (3), 2551–2558. 10.1021/nn305867d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lahitte JF; Pelascini F; Peruch F; Meneghetti SP; Lutz PJ Transition Metal-Based Homopolymerisation of Macromonomers. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2002, 5 (2), 225–234. 10.1016/s1631-0748(02)01369-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Li Z; Tang M; Liang S; Zhang M; Biesold GM; He Y; Hao SM; Choi W; Liu Y; Peng J; et al. Bottlebrush Polymers: From Controlled Synthesis, Self-Assembly, Properties to Applications. Progress in Polymer Science. 2021. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2021.101387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yavitt BM; Fei HF; Kopanati GN; Winter HH; Watkins JJ Power Law Relaxations in Lamellae Forming Brush Block Copolymers with Asymmetric Molecular Shape. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (4), 1557–1566. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).McBreen J; Lee HS; Yang XQ; Sun X New Approaches to the Design of Polymer and Liquid Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. J. Power Sources 2000, 89 (2), 163–167. 10.1016/S0378-7753(00)00425-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Stoeva Z; Martin-Litas I; Staunton E; Andreev YG; Bruce PG Ionic Conductivity in the Crystalline Polymer Electrolytes PEO6:LiXF6, X = P, As, Sb. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (15), 4619–4626. 10.1021/ja029326t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Molineux G Pegylation: Engineering Improved Biopharmaceuticals for Oncology. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23 (8 II). 10.1592/phco.23.9.3s.32886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Alconcel SNS; Baas AS; Maynard HD FDA-Approved Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Protein Conjugate Drugs. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2 (7), 1442–1448. 10.1039/c1py00034a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stephan AM Review on Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Eur. Polym. J. 2006, 42 (1), 21–42. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2005.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chiappetta DA; Sosnik A Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Poly(Propylene Oxide) Block Copolymer Micelles as Drug Delivery Agents: Improved Hydrosolubility, Stability and Bioavailability of Drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 66 (3), 303–317. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Li W; Yu Y; Lamson M; Silverstein MS; Tilton RD; Matyjaszewski K PEO-Based Star Copolymers as Stabilizers for Water-in-Oil or Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Macromolecules 2012, 45 (23), 9419–9426. 10.1021/ma3016773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bates CM; Chang AB; Momčilović N; Jones SC; Grubbs RH ABA Triblock Brush Polymers: Synthesis, Self-Assembly, Conductivity, and Rheological Properties. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (14), 4967–4973. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Quémener D; Chemtob A; Héroguez V; Gnanou Y Synthesis of Latex Particles by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Polymer (Guildf). 2005, 46 (4 SPEC. ISS.), 1067–1075. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.11.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rao N V; Ganivada MN; Sarkar S; Dinda H; Chatterjee K; Dalui T; Das Sarma J; Shunmugam R Magnetic Norbornene Polymer as Multiresponsive Nanocarrier for Site Specific Cancer Therapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25 (2), 276–285. 10.1021/bc400409n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shin D; Shin K; Aamer KA; Tew GN; Russell TP; Lee JH; Jho JY A Morphological Study of a Semicrystalline Poly(L-Lactic Acid-b-Ethylene Oxide-b-L-Lactic Acid) Triblock Copolymer. Macromolecules 2005, 38 (1), 104–109. 10.1021/ma0481712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Shi W; Han CC Dynamic Competition between Crystallization and Phase Separation at the Growth Interface of a PMMA/PEO Blend. Macromolecules 2012, 45 (1), 336–346. 10.1021/ma201940m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhu L; Cheng SZD; Calhoun BH; Ge Q; Quirk RP; Thomas EL; Hsiao BS; Yeh F; Lotz B Phase Structures and Morphologies Determined by Self-Organization, Vitrification, and Crystallization: Confined Crystallization in an Ordered Lamellar Phase of PEO-b-PS Diblock Copolymer. Polymer (Guildf). 2001, 42 (13), 5829–5839. 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00902-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chaoliang H; Sun J; Ma J; Chen X; Jing X Composition Dependence of the Crystallization Behavior and Morphology of the Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Diblock Copolymer. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7 (12), 3482–3489. 10.1021/bm060578m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Palacios JK; Zhao J; Hadjichristidis N; Müller AJ How the Complex Interplay between Different Blocks Determines the Isothermal Crystallization Kinetics of Triple-Crystalline PEO-b-PCL-b-PLLA Triblock Terpolymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (24), 9683–9695. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Sun H; Yu DM; Shi S; Yuan Q; Fujinami S; Sun X; Wang D; Russell TP Configurationally Constrained Crystallization of Brush Polymers with Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Side Chains. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (2), 592–600. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Theodosopoulos GV; Zisis C; Charalambidis G; Nikolaou V; Coutsolelos AG; Pitsikalis M Synthesis, Characterization and Thermal Properties of Poly(Ethylene Oxide), PEO, Polymacromonomers via Anionic and Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Polymers (Basel). 2017, 9 (4). 10.3390/polym9040145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Neugebauer D Graft Copolymer with Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Segments. Polym Int 2007, 56 (August), 1469–1498. 10.1002/pi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Onbulak S; Rzayev J Synthesis and One-Dimensional Assembly of Cylindrical Polymer Nanoparticles Prepared from Tricomponent Bottlebrush Copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2017, 55 (23), 3868–3874. 10.1002/pola.28771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Qiao C; Jiang S; Dong D; Ji X; An L; Jiang B The Critical Lowest Molecular Weight for PEG to Crystallize in Cross-Linked Networks. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004, 25 (5), 659–663. 10.1002/marc.200300113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Golitsyn Y; Pulst M; Samiullah MH; Busse K; Kressler J; Reichert D Crystallization in PEG Networks: The Importance of Network Topology and Chain Tilt in Crystals. Polymer (Guildf). 2019, 165 (January), 72–82. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kawaguchi S; Akaike K; Zhang ZM; Matsumoto H; Ito K Water Soluble Bottlebrushes. Polym. J. 1998, 30 (12), 1004–1007. 10.1295/polymj.30.1004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Müller MT; Yan X; Lee S; Perry SS; Spencer ND Lubrication Properties of a Brushlike Copolymer as a Function of the Amount of Solvent Absorbed within the Brush. Macromolecules 2005, 38 (13), 5706–5713. 10.1021/ma0501545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Schoch RL; Emilsson G; Dahlin AB; Lim RYH Protein Exclusion Is Preserved by Temperature Sensitive PEG Brushes. Polymer (Guildf). 2017, 132, 362–367. 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.10.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Deng J; Ma L; Liu X; Cheng C; Nie C; Zhao C Dynamic Covalent Bond-Assisted Anchor of PEG Brushes on Cationic Surfaces with Antibacterial and Antithrombotic Dual Capabilities. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 3 (4), 2–7. 10.1002/admi.201500473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Sun J; Stone GM; Balsara NP; Zuckermann RN Structure-Conductivity Relationship for Peptoid-Based PEO-Mimetic Polymer Electrolytes. Macromolecules 2012, 45 (12), 5151–5156. 10.1021/ma300775b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Li S; Jiang K; Wang J; Zuo C; Jo YH; He D; Xie X; Xue Z Molecular Brush with Dense PEG Side Chains: Design of a Well-Defined Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (19), 7234–7243. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rosenbach D; Mödl N; Hahn M; Petry J; Danzer MA; Thelakkat M Synthesis and Comparative Studies of Solvent-Free Brush Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2 (5), 3373–3388. 10.1021/acsaem.9b00211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wang D; Lin J; Jia F; Tan X; Wang Y; Sun X; Cao X; Che F; Lu H; Gao X; et al. Bottlebrush-Architectured Poly(Ethylene Glycol) as an Efficient Vector for RNA Interference in Vivo. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5 (2). 10.1126/sciadv.aav9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Alfred SF; Al-Badri ZM; Madkour AE; Lienkamp K; Tew GN Water Soluble Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Functionalized Norbornene Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46 (8), 2640–2648. 10.1002/pola.22594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Sarapas JM; Chan EP; Rettner EM; Beers KL Compressing and Swelling to Study the Structure of Extremely Soft Bottlebrush Networks Prepared by ROMP. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (6), 2359–2366. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani M; Daniel WFM; Everhart MH; Pandya AA; Liang H; Matyjaszewski K; Dobrynin AV; Sheiko SS Mimicking Biological Stress-Strain Behaviour with Synthetic Elastomers. Nature 2017, 549 (7673), 497–501. 10.1038/nature23673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Sheiko SS; Dobrynin AV Architectural Code for Rubber Elasticity: From Supersoft to Superfirm Materials. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (20), 7531–7546. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Mukherjee S; Xie R; Reynolds VG; Uchiyama T; Levi AE; Valois E; Wang H; Chabinyc ML; Bates CM Universal Approach to Photo-Crosslink Bottlebrush Polymers. Macromolecules 2020, 53 (3), 1090–1097. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Gandhewar N; Shende P Ionic Liquids: A State of the Art for Biomedical Applications. Ionics (Kiel). 2021, 27 (9), 3715–3728. 10.1007/s11581-021-04201-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Walker CN; Bryson KC; Hayward RC; Tew GN Wide Bicontinuous Compositional Windows from Co-Networks Made with Telechelic Macromonomers. ACS Nano 2014, 8 (12), 12376–12385. 10.1021/nn505026a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Cui J; Lackey MA; Madkour AE; Saffer EM; Griffin DM; Bhatia SR; Crosby AJ; Tew GN Synthetically Simple, Highly Resilient Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13 (3), 584–588. 10.1021/bm300015s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Rule JD; Moore JS ROMP Reactivity of Endo- and Exo-Dicyclopentadiene. Macromolecules 2002, 35 (21), 7878–7882. 10.1021/ma0209489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Yoon KH; Kim KO; Wang C; Park I; Yoon DY Synthesis and Structure-Property Comparisons of Hydrogenated Poly(Oxanorbornene-Imide)s and Poly(Norbornene-Imide)s Prepared by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50 (18), 3914–3921. 10.1002/pola.26171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Sutthasupa S; Shiotsuki M; Sanda F Recent Advances in Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization, and Application to Synthesis of Functional Materials. Polymer Journal. 2010, pp 905–915. 10.1038/pj.2010.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Kiselev SA; Lenev DA; Lyapkov AA; Semakin SV; Bozhenkova G; Verpoort F; Ashirov RV Reactivity of Norbornene Esters in Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization Initiated by a N-Chelating Hoveyda II Type Catalyst. RSC Advances. 2016, pp 5177–5183. 10.1039/c5ra25197d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Teo YC; Xia Y Facile Synthesis of Macromonomers via ATRP-Nitroxide Radical Coupling and Well-Controlled Brush Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (1), 81–87. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Teo YC; Xia Y Importance of Macromonomer Quality in the Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Macromonomers. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (16), 5656–5662. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Brunzel M; Majdanski TC; Vitz J; Nischang I; Schubert US Fast Screening of Diol Impurities in Methoxy Poly(Ethylene Glycol)s (MPEG)s by Liquid Chromatography on Monolithic Silica Rods. Polymers (Basel). 2018, 10 (12), 1–8. 10.3390/polym10121395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Trathnigg B; Ahmed H Separation of All Oligomers in Polyethylene Glycols and Their Monomethyl Ethers by One-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399 (4), 1535–1545. 10.1007/s00216-010-3951-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Sefisko B; Delgado C; Fisher D; Ehwald R Analysis and Purification of Monomethoxy-Polyethylene Glycol by Vesicle and Gel Permeation Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1993, 641 (1), 71–79. 10.1016/0021-9673(93)83460-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Dust JM; Fang ZH; Harris JM Proton NMR Characterization of Poly(Ethylene Glycols) and Derivatives. Macromolecules 1990, 23 (16), 3742–3746. 10.1021/ma00218a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (69).De Vos R; Goethals EJ End Group Analysis of Commercial Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Monomethyl Ether’s. Polym. Bull. 1986, 15 (6), 547–549. 10.1007/BF00281766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Rubinstein M; Colby RH Polymer Physics, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Sippel A Physical Properties of Polymers; 1958; Vol. 158. 10.1007/BF01840027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Shull KR; Ahn D; Chen W-L; Flanigan CM; Crosby, Alfred, J. Axisymmetric Adhesion Tests of Soft Materials. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1998, No. 199, 489–511. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Vatankhah-Varnoosfaderani M; Daniel WFM; Zhushma AP; Li Q; Morgan BJ; Matyjaszewski K; Armstrong DP; Spontak RJ; Dobrynin AV; Sheiko SS Bottlebrush Elastomers: A New Platform for Freestanding Electroactuation. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29 (2). 10.1002/adma.201604209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.