Abstract

Background

Substantive previous work has shown that both gait speed and global cognition decline as people age. Rates of their decline, as opposed to cross-sectional measurements, could be more informative of future functional status and other clinical outcomes because they more accurately represent deteriorating systems. Additionally, understanding the sex and racial disparity in the speed of deterioration, if any, is also important as ethnic minorities are at an increased risk of mobility disability and dementia.

Method

Data from 2 large longitudinal intervention studies were integrated. Rates of decline were derived from individual-level measures of gait speed of 400-m walk and scores on the Modified Mini Mental State Examination (3MSE). We also assessed age-associated declines and accelerations in changes across the ages represented in the studies (age range 53–90).

Results

The mean rate of decline in 400-m gait speed across individuals was 0.03 m/s per year, and multivariable analysis showed a significant acceleration in decline of −0.0013 m/s/y2 (p < .001). Both race and sex moderated the rate of decline. For global cognition, the mean rate of decline was 0.05 of a point per year on the 3MSE scale, and acceleration in the rate of decline was significant (−0.017 point/y2, p < .001), but neither sex nor race moderated the decline.

Conclusion

Rate of decline in physical but not cognitive function appears moderated by sex and race. This finding, as well as rates and accelerations of decline estimated herein, could inform future intervention studies.

Clinical Trials Registration Number

NCT00017953 (Look AHEAD); NCT01410097 (Look AHEAD ancillary); NCT00116194 (LIFE).

Keywords: Aging, Dual decliner, Rate of decline walking speed, Rate of decline cognition

The use of gait speed as a marker of physical function, and its relationship to other clinical outcomes, such as cognitive function, falls, and mortality, have been intensively studied (1–5). The speed of gait declines with age at approximately 1% per year from age 65 to 69 and which accelerate to 4% per year in adults older than 80 years (6,7). Moreover, systematic disparities in gait speed by socioeconomic factors have been reported (8).

Gait speed in older adults shows large variation. For example, in a sample of N = 95 older adults (mean age 79.4), mean gait speed was reported as 1.0 m/s with range 0.36–1.48 m/s.(9) Partly because of the large variation in gait speed in older adults, the measure of speed itself may not be the optimal indicator of physical function in aging studies, especially in predicting future clinical outcomes. In contrast to gait speed per se, the gradient (or rate of decline) in gait speed, and acceleration (rate of change in the rate of decline), with aging, have been studied far less. Measured for a given age range, the rate of decline, reflecting the speed of deterioration of a key mobility function, could be a sensitive and more informative measure of prospective functional status and other clinical outcomes. Additionally, understanding the disparity in the speed of deterioration, if any, is also important as the older American population becomes more racially diverse. Ethnic minorities, especially African Americans (AAs), for example, are at increased risk of dementia (10).

Many studies have examined racial and sex differences in physical and cognitive functioning (8,11), whereas others have explored the relationship between physical and cognitive function and disparity (2,12,13), with fewer having examined the relationship between their respective rates of decline. In most longitudinal studies, the individual-level rate of decline is not considered, nor are differential rates of decline and acceleration across subgroups such as race and sex. Current approaches that take the rate of decline into account at the population-level include trend-based analyses of gait speed that is often assumed to bear a linear relationship with age (14). For example, decline in gait speed has been characterized as change across 2 time points (14) or as indicated by the regression coefficients of a time-scale variable (15). Another approach that examines change in gait speed is trajectory analysis, which typically operates in 2 steps. In the first step, different classes of trajectories within a cohort (eg, no decline, intermediate decline, and severe decline) (16) are identified. As a next step, the identified classes are used for predictive analysis (eg, for mortality) (17). Although these approaches can inform how decline in gait speed is related to important clinical outcomes, they have limitations. For example, some studies have only used cross-sectional data in trend analyses by using age to indicate trend. An age cohort effect is thus ignored, potentially leading to a biased result unless there is no difference between age cohorts (18).

Research has consistently shown that gait speed is lower in AAs compared with non-Hispanic White Americans (19–21). Findings related to gender indicate either slower walking speeds for women (22) or no gender differences (23,24).

The rate of decline in global cognition has also not been as well studied as absolute measures of cognition. Decline in global cognition starts in middle age. The rate of decline is approximately 0.02–0.03 SD units per year for adults close to and under age 60, and about 0.04–0.05 SD units per year for age 61–96 (25). Many studies have assessed racial and sex differences in cognitive decline. Gender differences in global cognitive function largely show a more rapid decrease in women (26,27), although there more generally similarities across cognitive subdomains (28). The literature is relatively equivocal regarding racial differences in cognitive decline. It has been shown that AA adults have lower baseline cognitive scores that are largely explained by lower levels and quality of education. However, although some studies show a more rapid decline in AA (29,30), others show no differences (11,31). Therefore, more research is needed in this area from large studies following participants over a number of years.

In this article, our focus is on the rates of decline with aging in gait speed and global cognition. We also examined changes in rates of decline with time—that is, acceleration. Acceleration was measured because only knowing the average rate of decline may limit understanding of the pattern of change in gait or global cognition as people age. For example, decrease in gait speed due to the cumulative effect from an accelerated decline could be significant and signal a high risk of adverse outcomes.

We integrated data from 2 longitudinal intervention studies—the LIFE study (32) and the Look AHEAD Ancillaries (33,34) and Continuation (LA-AC) study (35), with a participant age range of 53–90. There were several reasons we selected these 2 data sets for an integrative analysis. Besides the obvious reason of increased sample size and power, the integrative data approach allows us to cover a broader range of age spectrum (LIFE mean [median] age = 78.9 [78.7], range = 70.0–89.9; LA-AC, mean [median] age = 67.6 [67.4], range = 53.0–85.0). Both studies also feature extended periods of follow-ups, which is important for studying rate of decline. Importantly, both studies collected robust and reliable measures of gait speed (400-m walk) and global cognitive (the Modified Mini Mental State Examination, 3MSE). In contrast to measures that use a shorter walking distance (eg, the commonly used 4-m walk component in the SPPB) to assess gait speed, the 400-m walk taps into gait speed during a physical demand that is known to be predictive of major mobility disability. Accordingly, the 400-m walk test is “an excellent proxy for community ambulation and central to maintaining a high quality of life and independence in the community” (32). The 3MSE (36) is a global measure of cognitive function with evidence of content validity, reliability, and sensitivity that are comparable to other commonly used measures including the MMSE, and yet demonstrates greater discriminability for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (37,38). Here, our goal is to (a) assess age-associated rates of decline and accelerations in gait speed and global cognitive function in adults and older adults across the ages represented in the studies (53–90 years old), (b) study disparity in the respective rates of decline by race and sex, and (c) explore possible relationships between rates of decline in gait speed and global cognitive function. We hypothesize that the rate of decline in gait speed is predictive of rate of decline in global cognition. Additionally, we examine the disparity in the characteristics of individuals who decline in both gait speed and global cognition (39).

Method

Data Sources

Two data sets, respectively, from the LIFE and LA-AC studies were first integrated. Both studies were multicenter randomized clinical trials with life-style interventions (physical activity, weight loss) and included data for adults of older age. Research protocols, including ethics statements regarding informed consent, confidentiality, and compliance with HIPPA, for those studies included in our analyses were approved by institutional review boards as documented in previous publications (32–35,40). Only deidentified data were used for analysis in this study.

In the current study, the age range in the sample was 53.0–90.0 years. In brief, the LIFE study (32) (from 2010 to 2015; with follow-ups at 6-month interval up to month 42 and 2 additional extended visits) enrolled men and women aged 70–89 years who were sedentary and at high risk for mobility disability, but could walk 400 m in less than 15 minutes without sitting, leaning, or the help of another person or walker (ie, no major mobility disability); had no major cognitive impairment; and could safely participate in the intervention as determined by medical history, physical examination, and resting electrocardiography. This data set included a total n = 1 586 participants.

The LA-AC were extensions of the Look AHEAD (LA) study (40) that recruited n = 5 145 individuals (from 2001 to 2004) who were overweight or obese and had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The age range of the participants in the original LA study was 45–76 years. The LA-AC contained 2 ancillary studies (the Movement and Memory Study (33) and the Look AHEAD Brain Study (34)) and the continuation study (35). The 2 ancillary studies collected cognitive assessment data during 5 years spanning the end of intervention and postintervention follow-up. For the LA Continuation study, cognition was assessed in the full cohort 10–13 years after enrollment and 1–2 years after intervention cessation. The combined sample size from the 3 studies in LA-AC was n = 3 751 participants. The current study used a subset of data from the LIFE and LA-AC studies that included participants with at least 2 observations for each measure of 400-m gait speed and 3MSE.

Measures

Gait speed and global cognitive function

The 400-m walk gait speed (m/s) test requires the participant to walk the distance and represents physical function. There were slight differences in how gait speeds were operationalized as an analytic variable between the LIFE and the LA-AC studies. In LIFE, gait speed was calculated for both completers (defined as completing 400 m in under 15 minutes) and noncompleters. For noncompleters in LIFE, gait speed was calculated as meters completed divided by time walked. For LA-AC, gait speed was set to missing for noncompleters. However, the difference in variable operationalization did not impact the result, as no noncompleter in LA-AC was included because none of them had 2 or more observations. The 3MSE is a measure of global cognitive function that includes items assessing orientation, memory, language, executive function, and visuoconstruction. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better global cognitive function.

Disparity factors

Race and ethnicity were assessed by self-report using standardized survey items. To align race/ethnicity across the 2 studies, we limited the analysis to 2 broad categories of race/ethnicity—White and AA. All other race/ethnic groups were collapsed into a single category of Others due to small cell sizes. Because age was used as a variable to indicate the time dimension, age was not defined as a factor for disparity. The LIFE and LA-AC studies had different follow-up schedules and intervals between follow-ups. We used chronological ages from both studies as a common reference measure for time-related measures in the analysis.

Other measures

Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), which was assessed in clinic, and the source study (Study) were considered as covariates for both the rate of decline in gait and the 3MSE outcomes. Other covariates measured at baseline included education (3 levels: <13, 13–16, >16 years of school), income (3 levels: <40 000, 40 000–80 000, >80 000), diabetes status, and physical activity/sedentary behavior, which was measured by total number of steps per day as captured by wearable accelerometer. Education level and income had slightly different categorizations for the 2 studies (32–35), and these variables were harmonized to allow for integrated analysis. The 2 studies also used different accelerometers (RT3 StayHealthy for LA-AC; ActiGraph wGT3X for LIFE) and different wearing protocols (eg, LA-AC on waist and LIFE on hip; LA-AC required ≥10 h/d; and LIFE required ≥18 h for 3 days). We converted the step measure to percentile within each study. Major mobility disability was not considered because only one person in LA-AC reported major mobility disability.

Statistical Analysis

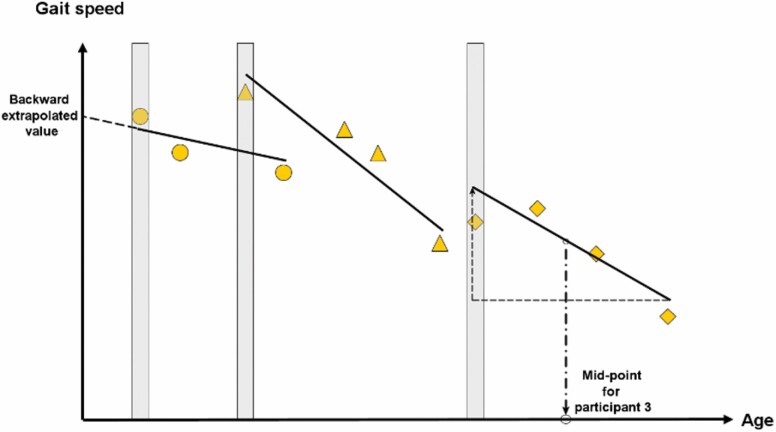

The current analysis used a 2-step procedure to derive individual rates of decline of physical and cognitive functions. To exploit the inclusion of participants from both intervention and control arms of the studies, in the first step we used regression analysis in which intervention status was treated as a fixed effect to remove the effect of intervention from each individual study. In the second step, we used data from the first step to derive individual estimates, respectively, for rates of decline in physical and cognitive functions for each participant. To achieve this goal, we applied an analysis to the data in which individual intercept and slope based on the longitudinal data were modeled as random effects. In other words, the trajectory of change during the period of observation was approximated by a straight line (Figure 1) in the model, and the intercepts and slopes of the individuals were assumed to follow the normal distribution. Accordingly, the slope represents the individual’s rate of decline during the period of observation, and the intercept represents function at a common reference age (defined as the minimum age in the sample) to which the straight line is “backward extrapolated.” Specifically, if Yij denotes 400-m gait speed for ith individual at the jth observation, then the random-effects model (Model 1), without including the error term, can be expressed as follows:

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the method for extracting information (intercept and slope) from the cohorts of the longitudinal gait-speed data using 3 participants (circle, triangle, and diamond, respectively, for participants 1, 2, and 3). Intercept (backward extrapolated value) is illustrated with participant 1 data; slope (rate of decline) is illustrated with participant 3 data. The age at which the instantaneous rate of decline is derived is set at the midpoint of the first and the last observation of the individual. The vertical bar indicates the first data point (baseline) collected for each participant, which can be used in the cross-sectional trend analysis.

| (1) |

where β 0i and β 1i, which respectively represent the individual-specific intercept and slope, and Tij is time (in years) from baseline. The random-effects β 0i and β 1i were assumed to follow normal distributions with means zero. A similar model was specified for 3MSE. The posterior modes of (β 0i, β 1i) conditional on the given values of Y and T from the random effect models were used for estimates of individual intercepts and slopes. The 2-step procedure allowed the reporting of descriptive statistics and analysis of individual rates of decline to facilitate interpretation. Subsequently, the slope estimates for β 1i in both gait speed and the 3MSE were treated as observed values for respective rates of decline and used in multivariable analysis.

Descriptive statistics for individual-specific rates of decline for gait speed and global cognition were used to summarize the data. Additionally, rates of decline were regressed on age, sex, race, and possible interactions between these factors, controlling for covariates. Because of different assessment schedules across the LIFE and LAC measures, the variable Age was operationalized separately for 400-m gait speed and the 3MSE—they were the mid-points between participants’ age at the first and last observations of the respective measure. Note that the number of observations for each individual varied from 2 to 9 for the 400-m walk, and 2 to 3 for the 3MSE (as previously pointed out, participants with only one observation were removed from the current analysis). The number of observations for an individual for each outcome variable was used as weight for the model.

To strive for a parsimonious model, we adopted a screening procedure for covariates. Besides the core variables of sex, race, age, and their interactions, we considered inclusion of covariates by first assessing the bivariate association between the dependent variable and the candidate variable, which were selected based on expert’s opinion, prior literature, and availability of data. An independent variable was included into the final model only if p < .1. The following covariates were considered: BMI, diabetes, physical activity/sedentary behavior, study (LA-AC vs LIFE), education, and income level.

For 400-m walk, the screening procedure identified BMI (p < .001) and income (p = .08) as covariates eligible for inclusion into the final model. Specifically, the following (weighted) model (Model 2) was considered for the rate of decline for 400-m gait speed:

| (2) |

where is the slope estimate from step 2, and Race and Sex are all indicator (categorical) variables.

Taken together, Models 1 and 2 exploit the longitudinal data and age range in the study cohorts to derive both the rate of decline and acceleration parameters from the data. The quantity γ 3 for example, quantifies the change of slope in 400-m gait speed with age, implying acceleration in decline if the value is negative. Disparity in slopes of decline for Sex and Race were, respectively, assessed through testing the hypotheses and . Disparity in accelerations of decline were respectively assessed by testing the hypotheses: (Sex), and (Race). To evaluate the robustness of the linear models, we further conducted sensitivity analyses, which included stratified analyses of study × intervention status. The way the final model for 3MSE was created was similar to that for 400-m walk. Sex, Race, Age, BMI, and Study were included into the final model. Finally, the rate of decline in gait speed was used as a predictor for rate of decline in the 3MSE, controlling for Sex, Race, Age, BMI, and Study in the linear regression analysis. To further examine possible interaction effects between declines in gait speed and global cognition, we categorized the participants into the following subgroups: no decline in both cognitive and physical function (ND; both individual-level slopes ≥ 0), decline in gait but not cognition (DG, slope for gait < 0, slope for 3MSE ≥ 0), decline in cognition but not gait (DC, slope for gait ≥ 0, slope for 3MSE < 0), and simultaneously decline in both (dual decliners, DD, both slopes < 0). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics, including the disparity factors, of the 4 derived subgroups. Chi-squared tests were used to test differences for categorical variables across the groups, and ANOVA was used to test differences for continuous variables, with a Dunnett-adjusted pairwise comparison to the ND group if the ANOVA result was significant.

Outcome variables of gait speed and 3MSE that contained missing values were treated as missing-at-random in the random-effects model that was used to derive individual-specific intercepts and slopes. The number of missing values for covariate variables were minimal and therefore observations for which covariates contained missing values were not included in the multivariable models. We used the R package lme4 and PROC GLM in SAS v9.4, respectively, for random effects and regression analysis. Two-sided tests were used for all hypothesis testing, and statistical significance was set at the α = .05 level.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

There were n = 2 679 participants included in the current analysis, with n = 1 586 from LIFE and n = 1 093 from LA-AC. The majority (63.7%) were female, 18.8% were AA, and the mean age was 74.7 years (SD = 8.1; range 53.0–89.9). The mean number of observations for gait-speed measurement was 6.8 (range 2–9), and the mean number of observations for the 3MSE was 2.8 (range 2–3). Depending on the study and measure, the mean length of observation period for participants ranged from 2.9 to 3.4 years. Lost to follow-up for LIFE was 4% annually (35) and 7%–10% for LA-AC (33,34). Detailed characteristics of participants of the entire sample, and by Race and Sex, are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the rates of decline and associations between decline in gait and global cognition, as well as estimated gait and cognition values at the reference age of 53 (Model 1, Figure 1). The mean decline rate of 400-m gait speed is −0.032 m/s/y; rates for AA and White participants are, respectively, −0.029 and −0.033 m/s/y, and rates for males and females are both −0.032 m/s/y. The mean rate of decline for the 3MSE is −0.054 points per year. Rates for AA and White participants are, respectively, −0.192 and −0.005 points per year, and rates for males and females are, respectively, −0.087 and −0.036. The correlations between 400-m gait, the 3MSE, and the respective rates of decline are provided in Supplementary Table S4. Notably correlation in the 3MSE and the reference age (53 years) 3MSE measurement is particularly high (r = .78; lower global cognition, faster rate of decline).

Table 1.

Descriptive Summary of 400-m Gait Speed, the 3MSE at Reference Age (53.0), and the Respective Rates of Decline

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decline rate of gait speed | −0.18 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Decline rate of 3MSE | −5.45 | 0.96 | −0.05 | 0.59 |

| 400-m gait speed* | 0.42 | 1.53 | 0.90 | 0.19 |

| 3MSE* | 71.52 | 98.11 | 92.15 | 3.99 |

Notes: 3MSE = Modified Mini Mental State Examination.

*400-m gait speed and 3MSE intercepts at the common reference age of 53.0.

Multivariable Analysis of Decline and Acceleration

There was no missing value for the predictors used in eqn (2) except for BMI (2 missing values). Not all participants had both outcome measures available. The respective sample sizes used in multivariable analyses were 1 362 (400-m gait speed) and 1 862 (3MSE).

For the analysis of the dependent variable of decline in gait speed, we included the following variables from Model 2 into the final model: Race, Sex, Age, Age × Sex, Age × Race, BMI, and Income. Statistically significant variables include Race (AA, p = .05), Age (p < .001), Age × Race (AA vs White, p = .04), BMI (p < .001), and Income (Medium vs Low, p = .05; Table 2). The AA group has a higher rate of gait speed decline by −0.036 m/s per year compared with White in the fully adjusted model. This comparison is specific to the reference age 53. Acceleration in rate of decline occurs at the rate of −0.0013 m/s/y2 (γ for Age in eqn (2)), and the acceleration in AA participants is not as sharp as in those who are White (reduced by 0.0005 m/s/y2). One unit of increase in BMI is associated with a change in rate of −0.0051 m/s/y. Results for the sensitivity analysis (stratified by study × treatment status, Supplementary Table S5) show that Age and BMI are consistently significant across the strata.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis for Slope in 400-m Gait Speed (m/s/y)

| Variable | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex* | −0.011 | 0.01 | .49 |

| Race* | |||

| AA | −0.0364 | 0.020 | .05 |

| Others† | 0.0176 | 0.030 | .52 |

| Age | −0.0013 | 0.0002 | <.001 |

| Age × Sex | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | .49 |

| Age × Race | |||

| Age × AA | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | .04 |

| Age × Others | −0.0002 | 0.0004 | .57 |

| BMI | −0.0051 | 0.0001 | <.001 |

| Income | |||

| Medium‡ | 0.0040 | 0.002 | .05 |

| High‡ | 0.0004 | 0.002 | .83 |

Notes: AA = African American; BMI = body mass index.

*Reference categories for Sex, Race, Income are respectively Male, White, and Low (<40 000).

†Others refer to participants that self-identified as Hispanic, multirace, and Asian/Pacific Islander.

‡Medium = 40 000–80 000; high = >80 000.

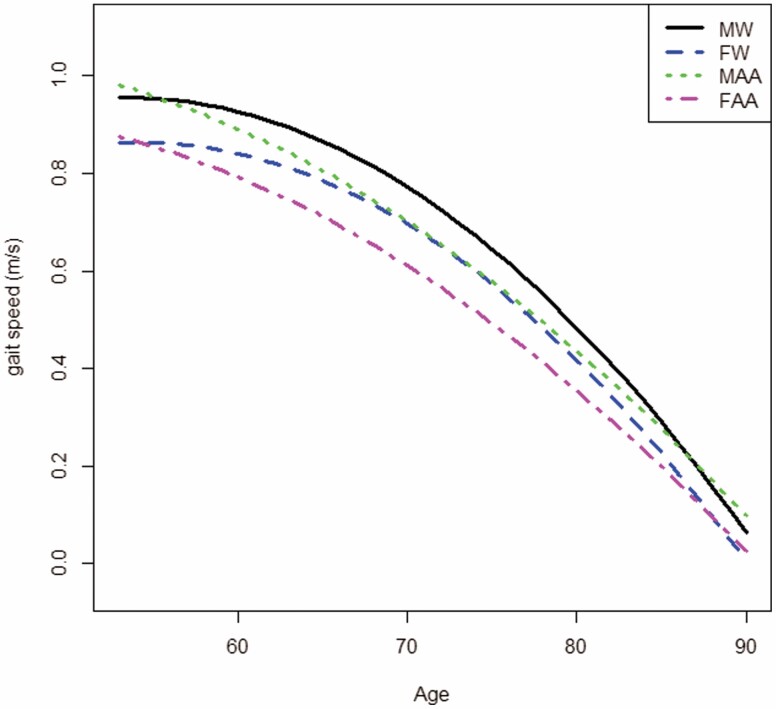

The result of the multivariable analysis for decline of gait speed in AA (AA had a higher rate of decline) seems to contradict results from examining the mean rate of decline in AA using the result from Model 1 where those who were AA had a lower overall rate of decline than those who were White. This is due to the presence of the acceleration represented by the interaction term between age and race in the multivariable analysis. To facilitate interpretation of results regarding disparity, we used the estimated rates of decline and acceleration from the model and plotted trajectories of gait speed for the 4 sex/race subgroups—male White (MW), female White (FW), male AA (MAA), and female AA (FAA; Figure 2). (The starting point of each subgroup was estimated using the subgroup mean of intercept estimates from Model 1 only using participants age < 65.)

Figure 2.

Model-based trajectories of 400-m walk gait speed for 4 major subgroups: Male White (MW), Female White (FW), Male African American (MAA), and Female African American (FAA). BMI is fixed at its mean value of 31.8.

For the dependent variable of decline in global cognition, Table 3 shows the results of the multivariable analysis. Specifically, race and acceleration of decline were highly significant (p < .001) as was Sex (p = .02). Results from sensitivity analysis show that some differences exist across the 2 studies (Supplementary Table S6). For example, Sex is significant in both LA-AC arms, but not in any of the LIFE study arm. Both Race (AA) and Age are significant in 3 of the 4 strata, whereas unlike the analysis in the entire sample, BMI is not significant in any stratum.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis for the Slope of (point/y)

| Variable | Estimate (Point) | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex* | 0.062 | 0.026 | .02 |

| Race* | |||

| AA | −0.242 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Others† | −0.257 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| Age | −0.017 | 0.002 | <.001 |

| BMI | 0.004 | 0.002 | .04 |

| Study | −0.075 | 0.03 | .03 |

Notes: AA = African American; BMI = body mass index.

aReference categories for Sex and Race are, respectively, Male and White.

†Others refer to participants that self-identified as Hispanic, multirace, and Asian/Pacific Islander.

Predictive Model and Dual Decliners

Regression analyses using rate of decline in cognition as a dependent variable and rate of decline of gait speed as primary predictors showed that rate of decline in gait speed, after controlling for Race, Sex, Age, BMI, and Study, was strongly associated with the rate of decline in global cognition (β = 2.79, 95% CI = [1.73, 3.85]; p < .001).

The distribution of the 4 categories (ND 6.6%, DG 51.3%, DC, 3.5%, DD, 38.6%) showed the majority of participants had decline in gait only or both. Details are summarized in Supplementary Table S7. The distributions of Sex and Race were not statistically significantly different across groups; that this was so despite large sample differences with respect to the DC group (eg, percentage of White in DC was 62 vs 75, 81, and 67 in ND, DG, and DD, respectively) may reflect low sample size (n = 74) in that group. The DD group was significantly older compared with the ND group. Additionally, in the DD group, in which dual declines may occur, the correlation between the rates of decline was significant (r = .23).

Discussion

We studied the changes in rate of decline in gait speed and global cognitive function in adults aged 53–90 years. Considered across all ages, decline in 400-m gait speed occurred in approximately 90% (1 894 of 2 107; see Supplementary Table S7) of the sample. Two disparity factors—sex and race—were examined as potential moderators of longitudinal changes.

Our analyses revealed that the mean rate of decline in 400-m gait speed across individuals was 0.03 m/s per year, and there was a highly significant acceleration of 0.0013 m/s/y2. To put this acceleration into perspective, in 10 years, the cumulative decline would be 0.37 m/s (10 × 0.03 + 0.5 × 0.0013 × 102 m/s) as opposed to 0.30 m/s (10 × 0.03 m/s) without acceleration.

AA participants had a higher rate of decline, but their acceleration rate was attenuated when compared with White participants. Therefore, disparity in gait speed should be interpreted within this context. From Figure 2, the rate of decline in “younger old” (52–65 years) AA was higher than those >65 years of age, whereas the reverse was true in those who were White.

Note that results from other studies have shown that 400-m gait speed has a distribution that is centered at approximately 1.05 m/s, which is almost 0.3 m/s less than gait speed measured by a 6-m walk and 0.5 m/s less than a 20-m walk (13). Thus, the overall percentage in rate of decline in 400-m gait speed is approximately 0.03/1.05 ≈3% per year. However, the current study reveals a more complex picture; decline in gait accelerates with aging, and rates of decline and acceleration vary by race and gender. The parabolic decline in gait speed suggests a substantially elevated risk for mobility disability, fall, and other adverse clinical outcomes that differs between AA and White, especially in the “old old.”

For global cognition, approximately 42% (888 of 2 107) of the sample exhibited some level of decline over the study period. The mean rate of decline was 0.05 of a point per year on the 3MSE scale. The analysis revealed that acceleration in the rate of decline was significant (−0.017 point/y2), but neither sex nor race moderated this effect. However, it is important to point out that AAs showed a significantly higher rate of decline compared with Whites (−0.24 of a point per year, p < .001), and females had a lower rate of decline compared with males (p = .02). To illustrate this disparity in decline, we use the groups MAA and MW. For participants aged <65 in these 2 groups, rates of decline were −0.25 point/y for MAA and −0.17 point/y for MW. Over 10 years, the cumulative declines for MAA and MW were 3.35 and 2.55 points, respectively. Using normed data, the SD of 3MSE in the 60- to 70-year-old adults’ was 7.9 points.(41) For participants 53–65 years old, the 10-year decline represents an average of 0.044 SD units of decline per year for MAA and 0.032 SD units for MW. The result is consistent with previous literature (25) and adds to the body of evidence on differences across groups defined by race as a social construct. Additionally, our result is consistent with Singer et al.’s finding that gradient is more negative in those with a mean age = 83.0 than those with a mean age = 73.7 (42). However, the Singer study found no difference in rate of decline between men and women and did not investigate race as a potential moderating variable.

Our findings regarding rates of decline in gait and global cognition provide some support to the cumulative disadvantage theory for health disparity (43), which postulates a systemic tendency for interindividual divergence in health due to the passage of time (44), implying health disparity to be a property of groups rather than individuals. It is possible that due to an accumulation of negative health events and stress across the life span, which increases health disparities particularly for AAs (45), this group shows sharper rates of decline in function later in life. Additionally, our analysis shows that the rate of decline in gait speed in “younger old” (52–65 years) AA was higher than in “older old” (>65 years), whereas the reverse was true in those who were White. This is consistent with a weathering hypothesis, which would posit that AA experience accelerated aging, but those who “make it” to older age are particularly robust.

Our analysis shows that rate of decline in gait speed was associated with rate of decline in global cognition. Previous studies have shown the association between physical function and cognitive function (2,13). There is evidence that older adults who experience a combined decline in both physical and cognitive function are more susceptible to dementia (46). Although our study showed significant association between rates of decline in gait speed and global cognitive, it did not identify significant associations of sex or race with rate of decline when comparing older adults who exhibit no decline in either physical or cognitive function when compared with those who experience dual decline. Power to identify such a difference might be compromised by small sample size in the DC group.

An interesting finding from the current study was the correlation between the rate of decline and the respective measure—gait speed and global cognition—at a common reference “baseline” age. For gait speed, the correlation was moderate (r = .37), whereas for global cognition (r = .78) it was remarkably strong (Supplementary Table S2). This could mean a potential “double jeopardy” effect for individuals with a low level of baseline global cognition as they age, as their reserve for the downside is lower, and the rate of decline is also higher. It is possible that a low 3MSE score at baseline indicates an active pathologic process in the brain, which eventually leads to faster rate of decline of global cognition. A caveat for this claim is that the backward extrapolated measure (intercept) can only serve as a crude proxy to the measure at a common reference age. Further investigation is needed to clarify this effect.

Both gait speed and global cognition are key measures of health (47). Their rates of decline signal critical transitions into different health states. Recent studies have investigated specific biomarkers that indicate common underlying biological mechanisms for such declines and transitions (48,49). If individual-level rates of decline and acceleration can be established as important markers of health for older adults, then further research is warranted to better understand how underlying physiological changes drive these markers and vice versa.

There are limitations to the current study. First, we used data from 2 large-scale randomized trials. To preserve sample size, we removed the intervention effect via statistical adjustment. While this approach has its limits, it needs to be recognized that for one study, the LA-AC, participant enrollment occurred either near the end of intervention or 1–2 years after cessation of intervention within the LA study. Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by study × intervention status, using the same model. For gait speed, Supplementary Table S5 shows that although estimates tend to vary across strata, the patterns of significance are similar to the entire sample. Key variables such as Age and BMI remain highly significant. We remark here that the control-only approach showed a rate of decline for 400-m gait speed of −0.03 (derived from descriptive statistics and not shown in table), which is almost identical to the value from the full-sample study. For 3MSE, unlike the result from the entire sample (Table 3), in which all included variables (Sex, Race, Age, and BMI) are significant, results from Supplementary Table S6 show that only some variables are significant in some strata. This suggests heterogeneity across strata and is also likely the result of reduced sample size due to stratification.

A second limitation is the different operationalizations for published analysis used in the LIFE and LA-AC studies for computing gait speed. Particularly, in LA-AC, setting noncompleted assessment in 400-m walk to missing could cause informative missingness. Our further analysis showed that there were 32 noncompleted gait assessments in the LA-AC sample. However, none of the participants with noncompleted gait assessment was included in the multivariable gait analysis because they did not have at least 2 gait measures due to noncompleted and missed assessments. While our analysis did not need to handle noncompleted gait assessment, it did not exempt the study from potential bias such as bias due to survival effect—that is, stronger individuals are more likely to survive to old age. However, as argued by Goodpaster et al. (50), cross-sectional studies are more prone to survival-effect bias, and the longitudinal approach of the current study alleviated much of this effect. Finally, the results may not be generalizable to a broader population. The LA-AC study consisted of participants with type 2 diabetes and BMI, indicating that overweight or obesity at baseline. Per protocol, the LIFE study enrolled relatively older (70+), inactive, and sedentary adults with compromised physical function. Overall, the current sample represents a slightly less healthy and more at-risk cohort of older adults. Despite these limitations, the studies examined represent older adults at high risk for adverse clinical outcomes and are commonly encountered within the context of geriatric medicine. Findings from the current study could inform future intervention studies that target higher-risk populations for preventing the development of adverse cognitive and/or physical health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Edward H Ip, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA; Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Shyh-Huei Chen, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

W Jack Rejeski, Department of Health and Exercise Science, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Karen Bandeen-Roche, Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Kathleen M Hayden, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Christina E Hugenschmidt, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

June Pierce, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Michael E Miller, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Jaime L Speiser, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Stephen B Kritchevsky, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Denise K Houston, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Robert L Newton, Jr., Population and Public Health, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA.

Stephen R Rapp, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Dalane W Kitzman, Sections of Cardiovascular and Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

Funding

The work is supported by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Coordinating Center grant U24 AG059624 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the Wake Forest Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, P30 AG049638-02 from the NIH. The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) Study is funded by cooperative agreement UO1AG22376 from the NIH and NIA; supplement 3U01AG022376-05A2S from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and was sponsored in part by the Intramural Research Program. The research is partially supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers at the University of Florida (1 P30 AG028740), Wake Forest University (1 P30 AG21332), Tufts University (1P30AG031679), University of Pittsburgh (P30 AG024827), and Yale University (P30AG021342) and the NIH/NCRR CTSA at Stanford University (UL1 RR025744), at University of Florida (U54RR025208) and at Yale University (UL1 TR000142). Tufts University is also supported by the Boston Rehabilitation Outcomes Center (1R24HD065688-01A1). LIFE investigators are also partially supported by the following: Dr Thomas Gill (Yale University) is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG3587) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr Carlos Fragoso (Spirometry Reading Center, Yale University) is the recipient of a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Roger Fielding (Tufts University) is partially supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement 58-1950-0-014. The LookAHEAD study was funded by the National Institutes of Health through cooperative agreements with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. Additional funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources. Additional support was received from the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (RR025758-04); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC; M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346). We further acknowledge the LookAHEAD ancillary studies—the Movement and Memory study, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (R01 AG03308701 and P30 AG21332), and the Brain Study, which is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (DK092237-01 and DK092237-02S2). The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R; Mortality Review Group. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4467–c4467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peel NM, Alapatt LJ, Jones LV, Hubbard RE. The association between gait speed and cognitive status in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;74(6):943–948. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tabbarah M, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. The relationship between cognitive and physical performance: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(4):M228–M235. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.m228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Welmer AK, Rizzuto D, Laukka EJ, Johnell K, Fratiglioni L. Cognitive and physical function in relation to the risk of injurious falls in older adults: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(5):669–675. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang C. Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A(8):896–901. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Himann JE, Cunningham DA, Rechnitzer PA, Paterson DH. Age-related changes in speed of walking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20(2):161–166. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198820020-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forrest KYZ, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA. Correlates of decline in lower extremity performance in older women: a 10-year follow-up study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1194–1200. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haas SA, Krueger PM, Rohlfsen L. Race/ethnic and nativity disparities in later life physical performance: the role of health and socioeconomic status over the life course. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2012;67B(2):238–248. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brach JS, Berthold R, Craik R, Van Swearingen JM, Newman AB. Gait variability in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1646–1650. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2001.49274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):580–586. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rea-Sandin G, Korous KM, Causadias JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of racial/ethnic differences and similarities in executive function performance in the United States. Neuropsychology. 2021;35(2):141–156. doi: 10.1037/neu0000715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deshpande N, Metter EJ, Bandinelli S, Guralnik J, Ferrucci L. Gait speed under varied challenges and cognitive decline in older persons: a prospective study. Age Ageing. 2009;38(5):509–514. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Handing EP, Rapp SR, Chen S-H, et al. Heterogeneity in association between cognitive function and gait speed among older adults: an integrative data analysis study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;76(4):710–715. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watson NL, Rosano C, Boudreau RM, et al. Executive function, memory, and gait speed decline in well-functioning older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65A(10):1093–1100. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Artaud F, Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Tzourio C, Elbaz A. Decline in fast gait speed as a predictor of disability in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jonkman NH, Del Panta V, Hoekstra T, et al. Predicting trajectories of functional decline in 60- to 70-year-old people. Gerontology. 2017;64(3):212–221. doi: 10.1159/000485135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. White DK, Neogi T, Nevitt MC, et al. Trajectories of gait speed predict mortality in well-functioning older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;68(4):456–464. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hofer SM, Sliwinski MJ, Flaherty BP. Understanding ageing: further commentary on the limitations of cross-sectional designs for ageing research. Gerontology. 2002;48(1):22–29. doi: 10.1159/000048920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. George KM, Gilsanz P, Peterson RL, et al. Physical performance and cognition in a diverse cohort: Kaiser Healthy Aging and Diverse Life Experiences (KHANDLE) Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2021;35(1):23–29. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiles Shaffer N, Simonsick EM, Thorpe RJ, Studenski SA. The roles of body composition and specific strength in the relationship between race and physical performance in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(4):784–791. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blanco I, Verghese J, Lipton RB, Putterman C, Derby CA. Racial differences in gait velocity in an urban elderly cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):922–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03927.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sialino LD, Schaap LA, van Oostrom SH, et al. The sex difference in gait speed among older adults: how do sociodemographic, lifestyle, social and health determinants contribute? BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inoue W, Ikezoe T, Tsuboyama T, et al. Are there different factors affecting walking speed and gait cycle variability between men and women in community-dwelling older adults? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(2):215–221. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0568-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chou MY, Nishita Y, Nakagawa T, et al. Role of gait speed and grip strength in predicting 10-year cognitive decline among community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1199-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salthouse TA. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(4):507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reas ET, Laughlin GA, Bergstrom J, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, McEvoy LK. Effects of sex and education on cognitive change over a 27-year period in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(8):889–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li LW, Ding D, Wu B, Dong X. Change of cognitive function in U.S. Chinese older adults: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(Suppl 1):S5–S10. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferreira L, Ferreira Santos-Galduróz R, Ferri CP, Fernandes Galduróz JC. Rate of cognitive decline in relation to sex after 60 years-of-age: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(1):23–31. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, Rabin JS, et al. Examining cognitive decline across black and white participants in the Harvard Aging Brain Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(4):1437–1446. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levine DA, Galecki AT, Langa KM, et al. Blood pressure and cognitive decline over 8 years in middle-aged and older black and white Americans. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):310–318. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weuve J, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Cognitive aging in black and white Americans: cognition, cognitive decline, and incidence of Alzheimer disease dementia. Epidemiology. 2018;29(1):151–159. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults. JAMA. 2014;311(23):23872387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Bray GA, et al. ; Action for Health In Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Movement and Memory Subgroup; Look AHEAD Research Group. Long-term impact of behavioral weight loss intervention on cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(9):1101–1108. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Espeland MA, Erickson K, Neiberg RH, et al. ; Action for Health in Diabetes Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Look AHEAD Brain) Ancillary Study Research Group. Brain and white matter hyperintensity volumes after 10 years of random assignment to lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(5):764–771. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rapp SR, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on cognitive function: Action for Health in Diabetes study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):966–972. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Teng EL, Chui HC, Schneider LS, Metzger LE. Alzheimer’s dementia: performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(1):96–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tombaugh TN, McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hubley AM. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Modified MMSE (3MS): a psychometric comparison and normative data. Psychol Assessment. 1996;8(1):48–59. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.8.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van Patten R, Britton K, Tremont G. Comparing the Mini-Mental State Examination and the modified Mini-Mental State Examination in the detection of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;31(5):693–701. doi: 10.1017/s1041610218001023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tian Q, Studenski SA, Montero-Odasso M, Davatzikos C, Resnick SM, Ferrucci L. Cognitive and neuroimaging profiles of older adults with dual decline in memory and gait speed. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;97:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–154. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1212914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones TG, Schinka JA, Vanderploeg RD, Small BJ, Graves AB, Mortimer JA. 3MS normative data for the elderly. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2002;17(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(00)00108-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singer T, Verhaeghen P, Ghisletta P, Lindenberger U, Baltes PB. The fate of cognition in very old age: Six-year longitudinal findings in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE). Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):318–331. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taylor MG. Timing, Accumulation, and the Black/White disability gap in later life. Res Aging. 2008;30(2):226–250. doi: 10.1177/0164027507311838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2003;58(6):S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vásquez E, Germain CM, Tang F, Lohman MC, Fortuna KL, Batsis JA. The role of ethnic and racial disparities in mobility and physical function in older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;39(5):502–508. doi: 10.1177/0733464818780631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Montero-Odasso M, Speechley M, Muir-Hunter SW, et al. Dual decline in gait speed and cognition is associated with future dementia: evidence for a phenotype. Age Ageing. 2020;49(6):995–1002. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Diehr PH, Thielke SM, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Tracy R. Decline in health for older adults: five-year change in 13 key measures of standardized health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(9):1059–1067. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Newman AB, Sanders JL, Kizer JR, et al. Trajectories of function and biomarkers with age: the CHS All Stars Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(4):1135–1145. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Waters DL, Vlietstra L, Qualls C, Morley JE, Vellas B. Sex-specific muscle and metabolic biomarkers associated with gait speed and cognitive transitions in older adults: a 9-year follow-up. GeroScience. 2020;42(2):585–593. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00163-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(10):1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.