Abstract

Expression of the histidine operon of Salmonella typhimurium is increased in dnaA(Ts) mutants at 37°C. This effect requires an intact his attenuator and can be suppressed by increasing the gene copy number of the hisR locus, which encodes the tRNAHis. We present data which suggest that the his deattenuation defect in dnaA(Ts) mutants results from the loss of a gene dosage gradient between the hisR locus, close to oriC, and the his operon, far from oriC. Some of the conclusions drawn here may apply to other operons as well.

In prokaryotes, the DnaA protein plays a central role in initiation of chromosomal replication. The protein binds to a specific 9-bp sequence, the DnaA box, which is repeated four times at the replication origin, oriC (13 [reviewed in reference 20]). Besides this primary function, DnaA acts as a transcription factor that can regulate the initiation or termination of transcription upon binding sequences related to DnaA boxes found in various genes (21). In this study, we describe an additional locus whose expression is influenced by the DnaA protein: the histidine biosynthetic operon of Salmonella typhimurium. The his operon is transcribed from the primary promoter (P1), but the main regulation results from a translation-dependent transcription attenuation mechanism whereby transcriptional levels are inversely correlated with the levels of histidyl-tRNAHis in the cell (16 [reviewed in reference 32]). This system is very finely tuned, since as little as a 50% reduction in histidyl-tRNAHis causes severalfold his deattenuation (18). Several his regulatory mutants affected in tRNAHis biosynthesis have been described, including two classes resulting from changes in the closely linked genes for RNase P (rnpA [6]) and DNA gyrase (gyrB [24]). The possibility that additional mutations mapping in the same region might be dnaA alleles has been suggested (24).

Deattenuation of a chromosomal his-lac fusion in dnaA(Ts) strains at semipermissive temperature.

Two thermosensitive dnaA alleles that prevent growth at 42°C, dnaA727 and dnaA747 (kindly provided by Russ Maurer, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio), were used in this study (Table 1). Introduction of either of these mutations into a strain carrying a his-lac chromosomal operon fusion (hisC9968::MudJ) results in an increase in β-galactosidase activity that is moderate (twofold) at 28°C and becomes substantial (eight- to ninefold) at 37°C, a temperature still permissive for growth (Table 2). In principle, such an increase in his operon expression might be ascribed either to a negative effect of the DnaA protein on the his promoter or to a positive role on the attenuation mechanism. To distinguish between these possibilities, the effect of the dnaA747 allele was analyzed in a strain carrying a his attenuator deletion (hisO1242 [16]). Results in Table 3 show that the dnaA-dependent increase in his-lac expression is abolished when the attenuator is absent. Similar results were obtained upon replacing the hisC9968::MudJ operon fusion with a protein fusion (15) (hisD2504::MudK) that generates approximately 100-fold-less β-galactosidase activity (data not shown), indicating that failure to observe a β-galactosidase increase is not attributable to the enzyme levels exceeding the measurable range. These findings rule out the his operon P1 promoter as the target of the DnaA protein and suggest that increased operon expression results from transcription deattenuation. A direct role of the protein on attenuator function is unlikely, due to the absence of sequences resembling a DnaA box at or near this site. The results presented below suggest that the DnaA protein affects the attenuation mechanism indirectly, by influencing the level of expression of the hisR locus, the single-copy gene encoding tRNAHis (5).

TABLE 1.

S. typhimurium strains and plasmids used in this study

| Straina or plasmid | Genotypeb | Source or referencec |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RM374 | dnaA727 zid-1257::Tn10dTc | 19 |

| RM595 | dnaA747 zid-2025::Tn10dKm | R. Maurer |

| RM135 | dnaC141 zji-1255::Tn10 thyA2 deo | 19 |

| RM2937 | dnaC602 zji-8183::Tn10 thyA2 deo | 19 |

| DEH38 | zdi-6798::Tn10dTet proU2881::MudJ | D. El-Hanafi |

| MA785 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-1257::Tn10dTc dnaA747 | |

| MA786 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-1257::Tn10dTc | |

| MA922 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm dnaA747 zdi-6798::Tn10dTc | |

| MA923 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm zdi-6798::Tn10dTc | |

| MA2847 | zgb-6784::Tn10dTc | 4 |

| MA4522 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zid-1257::Tn10dTc dnaA727 | |

| MA4526 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zid-1257::Tn10dTc dnaA747 | |

| MA4527 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zid-1257::Tn10dTc | |

| MA4528 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) hisR10107 zid-1257::Tn10dTc dnaA747 | |

| MA4529 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) hisR10107 zid-1257::Tn10dTc | |

| MA4530 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zji-1255::Tn10 dnaC141 | |

| MA4534 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zji-8183::Tn10 dnaC602 | |

| MA4535 | hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zji-8183::Tn10 | |

| MA4764 | hisO1242 hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zid-1257::Tn10dTc dnaA747 | |

| MA4765 | hisO1242 hisC9968::MudJ(Km) zid-1257::Tn10dTc | |

| MA4870 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm dnaA747/pACYC184 | |

| MA4871 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm dnaA747/ptRNAHisCCA | |

| MA4872 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm/pACYC184 | |

| MA4873 | hisC9968::MudA(Ap) zid-2025::Tn10dKm/ptRNAHisCCA | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Tcr Cmr | 9 |

| ptRNAHisCCA | Tcr; pACYC184 derivative that carries the entire hisR locus | 23 |

| pTS1 | Apr Tcr; pUC18 derivative that carries a 5.3-kb BamHI chromosomal DNA fragment from strain MA2847 including the Tn10dTc element and adjacent material |

All bacterial strains are derived from S. typhimurium LT2. Bacteria were grown in nutrient broth (NB) medium throughout this study. Strain construction was performed as previously described (11).

When appropriate, the “z” designation of transposon insertions was revised according to the latest edition of the Salmonella genetic map (26). MudA (Apr) refers to a conditionally transposition-defective derivative of the phage Mud1 constructed by Hughes and Roth (14). MudJ (Knr) refers to phage Mud1–1734 constructed by Castilho et al. (7). The hisC-Mud fusions used in this work were previously described (11).

Where not specified, the source of the strain is this work.

TABLE 2.

Effect of dnaA(Ts) mutations on expression of a his-lac operon fusion at 28 and 37°Ca

| Strain | dnaA allele | β-Galactosidase activity in Miller units (deattenuation ratio)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 28°C | 37°C | ||

| MA4527 | Wild type | 93 (1.0) | 110 (1.0) |

| MA4526 | dnaA747 | 206 (2.2) | 994 (9.0) |

| MA4522 | dnaA727 | 220 (2.4) | 863 (7.8) |

Bacterial cultures were grown overnight at 28°C in nutrient broth (NB), diluted 1 to 200, and incubated under aerobic conditions at 28 or 37°C in NB. Cell growth was monitored spectrophotometrically. At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 to 0.4, cell cultures were chilled on ice, and β-galactosidase activity was measured in toluene-permeabilized cells as described previously (22); the reported values represent the averages of at least three independent determinations. The standard error was below 10% in all cases.

TABLE 3.

Effect of hisO1242 and hisR10107 mutations on his-lac expression at 37°C in the presence or absence of the dnaA747 allelea

| Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| dnaA+ | dnaA747 | |

| hisO+ hisR+ | 110 | 994 |

| hisO1242 hisR+ | 4,670 | 3,898 |

| hisO+ hisR10107 | 84 | 1,011 |

Suppression of his deattenuation in a dnaA mutant by increasing the hisR gene dosage.

Isogenic strains carrying the dnaA747 mutation or its wild-type allele and a his-lac fusion, were transformed by ptRNAHis CCA, a recombinant plasmid carrying the entire hisR locus (23), or by parental vector pACYC184. The resulting strains (MA4870, MA4871, MA4872, and MA4873) were grown in nutrient broth medium supplemented with tetracycline (5 μg/ml), and β-galactosidase enzyme activity was assayed as described in Table 2, footnote a. The β-galactosidase activities of the dnaA+ and dnaA747 strains were 120 and 861 Miller units, respectively, with plasmid pACYC184 and 30 and 24 Miller units, respectively, with plasmid ptRNAHisCCA. Thus, increasing the hisR gene dosage has two noticeable effects: (i) it causes a reduction in the basal level of his operon expression regardless of the dnaA allele, and (ii) it completely suppresses dnaA-dependent deattenuation. The former effect is consistent with the notion that the his operon is incompletely repressed in rich medium (32) and suggests that this reflects limiting tRNAHis levels. The latter effect strongly suggests that his deattenuation in dnaA mutants results from a shortage of tRNAHis.

A potential DnaA box within the hisR promoter sequence is not involved in his deattenuation.

Examination of the nucleotide sequence of the hisR promoter region reveals that the segment between positions −12 and −4 (TTATCCACC in the nontemplate strand) matches exactly the consensus sequence for a DnaA box as defined by Schaefer and Messer (27). Thus, a tentative explanation for the his-deattenuated phenotype of dnaA mutants is that binding of DnaA protein to the hisR promoter is required for its optimal activity. The availability of a promoter mutation affecting the potential DnaA box allowed this hypothesis to be tested. Mutation hisR10107 causes a C/G to T/A base pair change at the 6th position of the DnaA box (TTATCTACC [11]). This is a highly conserved position, and its alteration in different DnaA boxes was shown to reduce binding by the DnaA protein (13, 27). Thus, one might expect that the hisR10107 change should either impair hisR promoter activity—resulting in his deattenuation even in a dnaA+ background—or render the promoter independent of DnaA protein activity, thereby suppressing the deattenuation defect of dnaA mutants. The results in Table 3 show that the hisR10107 mutation does neither of the above. The mutant promoter behaves like the wild-type promoter in its response to the dnaA alteration. This contrasts with the effect of the hisR10107 mutation on the promoter sensitivity to negative DNA supercoiling: in facilitating the promoter-opening step, the C/G-to-T/A base pair change renders the promoter insensitive to defects in DNA gyrase (11, 12). Overall, these results tend to indicate that the link between the DnaA protein and his regulation may not involve a direct interaction between the protein and the hisR promoter.

dnaC mutations cause his deattenuation.

The DnaC protein is required for initiation of DNA replication at a later stage than the DnaA protein (20). Mutations dnaC141 and dnaC602 result in thermosensitive alleles (19) that are not completely lethal, allowing some residual DNA synthesis and cell growth to take place at 43°C (13a). Both alleles were introduced in the his::MudJ genetic background, and β-galactosidase levels were measured as a function of temperature. The results showed a threefold increase in his expression when cells are grown at 43°C relative to cells grown at 28°C (Table 4). Although this increase is less dramatic than that observed with the dnaA mutants, the trend is clearly the same, and the smaller magnitude of the effects is ascribable to the “leaky” character of the dnaC alleles. These data strongly suggest that the his deattenuation defect is consequent to a defect in initiation of DNA replication and is independent of the nature of the initiation function affected.

TABLE 4.

Effect of dnaC(Ts) mutations on his-lac expression at 28 and 43°Ca

| Strain | dnaC allele | β-Galactosidase activity in Miller units (deattenuation ratio)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 28°C | 43°C | ||

| MA4535 | Wild type | 93 (1.0) | 119 (1.0) |

| MA4530 | dnaC141 | 103 (1.1) | 395 (3.3) |

| MA4534 | dnaC602 | 90 (1.0) | 396 (3.3) |

Bacterial cultures were grown overnight at 28°C in nutrient broth (NB), diluted 1 to 200, and incubated at 28 or 43°C in NB. β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described in the footnote to Table 2.

his deattenuation in a dnaA mutant correlates with the loss of the gene dosage gradient between hisR and his loci.

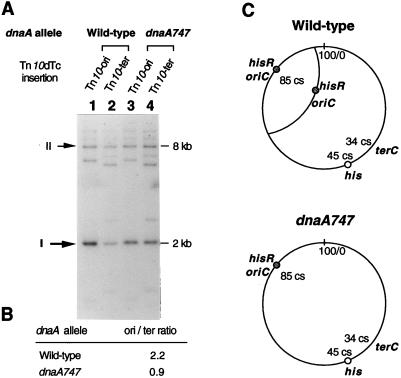

In fast-growing bacteria, the time interval separating consecutive rounds of initiation of DNA replication is shorter than the time needed for each elongation cycle to go to completion. As a result, fast-growing bacteria have multiple replication forks, and genes that are near the origin of replication are normally present at a higher copy number than genes located in the terminus region (8, 10). The existence of such a gene dosage gradient has been inferred from measuring the expression of reporter genes introduced at various chromosomal positions (28, 30) and demonstrated by quantitative Southern hybridization analyses (2). In S. typhimurium, the oriC site is located at 85 map units on the genetic map (26). The terC site has never been exactly mapped, but it is likely to be around 34 map units, at the equivalent position as in Escherichia coli. From the positions of hisR and his biosynthetic loci at 85 and 45 map units, respectively, one predicts that, in rich medium, the hisR gene dosage should be in excess relative to the his operon. Conceivably, this imbalance might be essential to attain the tRNAHis levels needed for full attenuation of his operon transcription. In order to test this possibility, we studied the effects of a dnaA mutation on the relative dosage of the same DNA sequence inserted near oriC or near terC. Chromosomal DNA from strains carrying a Tn10dTc element (Tn10Δ16Δ17 Tcr [31]) inserted either at 84 cs or at 38 cs was extracted from exponentially growing cells as described previously (3), digested with HpaI restriction endonuclease, and subjected to Southern analysis by using 32P-labelled DNA from a plasmid carrying the Tn10dTc element and sequences from the 62-cs region as a hybridization probe (Fig. 1A). For each lane in Fig. 1A, the Tn10dTc-specific 2-kb hybridization signal was quantified and normalized to the signal from the 62-cs sequence. In agreement with previous data (2), our results showed that, in the wild-type strain, the Tn10dTc element is amplified approximately twofold when located near oriC, compared to that when present in the terminus region (Fig. 1B). In contrast, this amplification is lost in the dnaA747 mutant strain in which oriC- and terC-proximal sequences occur in equimolar amounts (Fig. 1B). Clearly, these data support the idea that the his deattenuation defect of DNA replication initiation mutants reflects a decrease in the hisR/his operon dosage ratio consequent to the decrease in the frequency of initiation events (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Effect of the dnaA747 allele on the relative gene dosage of oriC-proximal DNA sequences relatively to terC-proximal DNA sequences. Strains carry a chromosomal Tn10dTc insertion located either in the proximity of oriC (Tn10-ori; zid-1257::Tn10dTc) or in the proximity of terC (Tn10-ter; zdi-6798::Tn10dTc). (A) Southern blot analysis of HpaI-digested chromosomal DNA hybridized with labeled pTS1 plasmid. Cells were grown overnight at 28°C in nutrient broth (NB), diluted 1 to 200, and incubated at 37°C in NB until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 was reached. Chromosomal DNA was extracted as described previously (3). DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane by capillarity under alkaline conditions (25). The membrane was hybridized to plasmid pTS1 DNA labeled with [α-32P]CTP by nick translation (25). Plasmid pTS1 is a pUC18 (New England Biolabs) derivative carrying a 5.3-kb DNA insert which includes a Tn10dTc element (2.9 kb) and sequences from the region flanking the argV locus of S. typhimurium (4). In the experiment described above, pTS1 DNA hybridizes to a 2-kb fragment from the internal portion of Tn10dTc (band I) and to an 8-kb fragment from the argV region (band II). (The size of the latter fragment is reduced in a strain carrying an argV deletion [4]. Additional signals result from hybridization to the ends of Tn10dTc and to the Apr gene of the MudA element.) The strains used were MA786 (lane 1), MA923 (lane 2), MA785 (lane 3), and MA922 (lane 4). (B) Quantification of the relative gene dosage between oriC-proximal and terC-proximal Tn10dTc insertions. For each lane, the hybridization signal of band I was normalized to the signal of band II by using a 400S PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The oriC/terC ratio was calculated for both dnaA+ and dnaA747 strains by dividing normalized signals corresponding to the Tn10-ori insertion by normalized signals corresponding to the Tn10-ter insertion. (C) Model in which the hisR locus is amplified relative to the his locus in a wild-type strain but not in the dnaA747 mutant at 37°C. Reduction of the hisR gene dosage in a dnaA strain is responsible for deattenuation of his operon transcription. The positions of the different loci are indicated in centisomes.

Implications and conclusions.

We propose a novel model for how dnaA alterations can affect gene expression and regulation. In this model, the DnaA protein does not act directly as a transcriptional regulator, but rather it influences transcription indirectly, through its role in DNA replication initiation, by modulating the relative copy number of a regulator gene and its target. The his operon might not be the only example of this form of control. In E. coli, expression of another biosynthetic operon regulated by attenuation, the trp operon, has been shown to be higher in a dnaA mutant (1). This effect was explained by postulating a direct role for the DnaA protein in the attenuation mechanism; however, no obvious DnaA boxes are found in the trp attenuator region, as already noticed by Messer and Weigel (21). From the analogies between the trp and his regulatory systems, we believe that the model proposed above can apply to the trp operon as well. Like tRNAHis, the tRNATrp is encoded by a unique gene, trpT, located near oriC, whereas the trp operon is located near terC, suggesting that the copy ratio between trpT and the trp operon changes as a result of variations in DNA replication initiation frequency. In E. coli, histidine and tryptophan are both recognized by unique isoacceptor tRNAs encoded by single-copy genes (17). Conceivably, the increased ploidy of tRNAHis and tRNATrp genes that results from the multiplicity of replication forks might be important for optimizing translational rates in fast-growing cells. The lack of effects of dnaA mutations on two additional attenuation-controlled operons tested, the thr operon (1) and leu operon (our unpublished data), is consistent with threonine and leucine being amino acids recognized by multiple tRNA species encoded in several loci scattered around the chromosome (17).

The chromosomal gene dosage gradient flattens out as the growth rate decreases (10, 28). Therefore, one predicts that some deattenuation of his operon transcription should occur in slow-growing bacteria, even if histidine is supplied to the medium. The basal levels of his operon expression are indeed higher in poor medium relative to rich medium (reference 33 and our unpublished data); however, this difference was shown to be independent of the his attenuator and mainly results from ppGpp-mediated stimulation of the his P1 promoter (29). This suggests that, under nutrient-limited conditions, excess hisR gene dosage with respect to the his operon is not required for full attenuation. Perhaps the smaller demand for histidine in protein synthesis in bacteria growing in an unsupplemented medium causes histidyl-tRNAHis levels to be high enough to ensure his attenuation regardless of the ploidy of the hisR gene.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Russ Maurer for the gift of dnaA and dnaC strains. We thank Eloi Gari for performing thymidine incorporation experiments with dnaA and dnaC mutants and Arden Aspedon and anonymous referees for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and by the pharmaceutical company Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung T, Hansen F G. Effect of dnaA and rpoB mutations on attenuation in the trp operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:985–992. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.3.985-992.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlung T, Hansen F G. Three distinct chromosome replication states are induced by increasing concentrations of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6537–6545. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6537-6545.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc-Potard A-B, Bossi L. Phenotypic suppression of DNA gyrase deficiencies by a deletion lowering the gene dosage of a major tRNA in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2216–2226. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2216-2226.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossi L. The hisR locus of Salmonella: nucleotide sequence and expression. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;192:163–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00327662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossi L, Cortese R. Biosynthesis of tRNA in histidine regulatory mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4:1945–1956. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.6.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castilho B A, Olfson P, Casabadan M J. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-Mu bacteriophage transposons. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:488–495. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.488-495.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler M G, Pritchard R H. The effect of gene concentration and relative gene dosage on gene output in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;138:127–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02428117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper S, Helmstetter C E. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol. 1968;31:519–540. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueroa N, Wills N, Bossi L. Common sequence determinants of the response of a prokaryotic promoter to DNA bending and supercoiling. EMBO J. 1991;10:941–949. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueroa-Bossi N, Guerin M, Rahmouni R, Leng M, Bossi L. The supercoiling sensitivity of a bacterial tRNA promoter parallels its responsiveness to stringent control. EMBO J. 1998;17:2359–2367. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuller R S, Funnell B E, Kornberg A. The dnaA protein complex with the E. coli chromosomal replication origin (oriC) and other DNA sites. Cell. 1984;38:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Gari, E., and L. Bossi. Unpublished data.

- 14.Hughes K T, Roth J R. Conditionally transposition-defective derivative of Mu d1(Amp Lac) J Bacteriol. 1984;159:130–137. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.130-137.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes K T, Roth J R. Transitory cis complementation: a method for providing transposition functions to defective transposons. Genetics. 1988;119:9–12. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston H M, Barnes W M, Chumley F G, Bossi L, Roth J R. Model for regulation of the histidine operon of Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:508–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komine Y, Adachi T, Inokuchi H, Ozeki H. Genomic organization and physical mapping of the transfer RNA genes in Escherichia coli K12. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:579–598. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90224-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis J A, Ames B N. Histidine regulation in Salmonella typhimurium. XI. The percentage of transfer RNAHis charged in vivo and its relation to the repression of the histidine operon. J Mol Biol. 1972;66:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(72)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer R, Osmond B C, Shekhtman E, Wong A, Botstein D. Functional interchangeability of DNA replication genes in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli demonstrated by a general complementation procedure. Genetics. 1984;108:1–23. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messer W, Weigel C. Initiation of chromosome replication. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1579–1601. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messer W, Weigel C. DnaA initiator—also a transcription factor. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3171678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor M, Willis N M, Bossi L, Gesteland R F, Atkins J F. Functional tRNAs with altered 3′ ends. EMBO J. 1993;12:2559–2566. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudd K E, Menzel R. his operons of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium are regulated by DNA supercoiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:517–521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanderson K E, Hessel A, Rudd K E. Genetic map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VIII. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:241–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.241-303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer C, Messer W. DnaA protein/DNA interaction. Modulation of the recognition sequence. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:34–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00273584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid M B, Roth J R. Gene location affects expression level in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2872–2875. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2872-2875.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shand R F, Blum P H, Mueller R D, Riggs D L, Artz S W. Correlation between histidine operon expression and guanosine 5′-diphosphate-3′-diphosphate levels during amino acid downshift in stringent and relaxed strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:737–743. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.737-743.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sousa C, de Lorenzo V, Cebolla A. Modulation of gene expression through chromosomal positioning in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997;143:2071–2078. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Way J C, Davis M A, Morisato D, Roberts D E, Kleckner N. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene. 1984;32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winkler M E. Biosynthesis of histidine. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 485–505. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkler M E, Roth D J, Hartman P E. Promoter- and attenuator-related metabolic regulation of the Salmonella typhimurium histidine operon. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:830–843. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.2.830-843.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]