Abstract

hydA and hydB, the genes encoding the large (46-kDa) and small (13.5-kDa) subunits of the periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 7757, have been cloned and sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence of the genes product showed complete identity to the sequence of the well-characterized [Fe] hydrogenase from the closely related species Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough (G. Voordouw and S. Brenner, Eur. J. Biochem. 148:515–520, 1985). The data show that in addition to the well-known signal peptide preceding the NH2 terminus of the mature small subunit, the large subunit undergoes a carboxy-terminal processing involving the cleavage of a peptide of 24 residues, in agreement with the recently reported data on the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme (Y. Nicolet, C. Piras, P. Legrand, E. C. Hatchikian, and J. C. Fontecilla-Camps, Structure 7:13–23, 1999). We suggest that this C-terminal processing is involved in the export of the protein to the periplasm.

Two main groups of hydrogenase are present in sulfate-reducing bacteria of the genus Desulfovibrio, one containing either nickel or nickel and selenium atoms in addition to iron-sulfur clusters ([NiFe] hydrogenases and [NiFeSe] hydrogenases) and one, of higher activity, containing exclusively iron-sulfur clusters ([Fe] hydrogenases) (8). The widespread nickel-containing hydrogenases have been intensively studied (2, 24), and the crystal structure of the [NiFe] hydrogenase of two Desulfovibrio species was determined (14, 34, 35). In contrast, [Fe] hydrogenases form a small family of proteins isolated exclusively from anaerobic microorganisms (1). Both types of hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio species are heterodimers, which differ in their metal center composition, amino acid sequences, mechanistic properties, sensitivity to inhibitors, and immunological properties (1, 2, 8, 40). They are usually located in the periplasmic space, where they play a major role in the energy metabolism of these microorganisms (19, 21, 32). The mature small subunits of the two types of hydrogenase are preceded by a complex NH2-terminal sequence (34 amino acid residues for the [Fe] hydrogenase and 50 amino acid residues for the [NiFe] hydrogenase), while the large subunits lack an NH2-terminal signal peptide (39, 40). All potential signal sequences from periplasmic hydrogenases contain a unique strictly conserved element (R-R-X-F-X-K), suggesting that these enzymes are exported to the periplasm via an unusual mechanism of membrane translocation (33, 39). In addition to the NH2-terminal signal peptide of the small subunit, it was shown that the large subunit of [NiFe] hydrogenase undergoes a C-terminal processing associated with the incorporation of nickel in the protein, as reported first for the Azotobacter vinelandii (9) and Escherichia coli (27) enzymes.

The periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 7757, which has previously been characterized, exhibited a molecular mass of 53.5 kDa and comprises two different subunits of 42.5 and 11 kDa (13). Electron paramagnetic resonance studies allowed the identification of two ferredoxin-type [4Fe-4S]1+ clusters and one atypical cluster (H cluster) involved in H2 activation and proposed to be a [6Fe-6S]-type cluster (13). The molecular properties, N-terminal amino acid sequences of both subunits, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and catalytic properties of the D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase are highly similar to those of the well-characterized [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough (11, 12, 22, 23, 37).

Although it was not clear from the sequence how [Fe] hydrogenase is exported to the periplasm, since the large subunit lacks a leader sequence, it was proposed that a single signal peptide containing the double-arginine motif operates in the export of both subunits (3, 20, 40). The determination of the three-dimensional structure of D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase has shown very recently (18) that the chain tracing of the large subunit in the electron density map could not be extended beyond Ala397, which is 24 amino acid residues from the C-terminal Ala 421 as determined by gene sequencing. In the present study, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding the hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 and showed on the basis of accurate determination of the molecular mass of its large subunit by mass spectrometry and from its C-terminal amino acid sequence that it lacks a region of 24 C-terminal amino acids encoded by the gene for the large subunit.

Nucleotide sequence of the [Fe] hydrogenase genes from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757.

D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 was grown at 37°C in a basic lactate-sulfate medium (29). Two sets of degenerate oligonucleotides based on the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal regions of the large and small subunits of D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase (13) were synthesized: DOP1 (5′ ATH GAR TAY GAR ATG CAY AC 3′) and DOP2 (5′ CAT RTA RTC YTT DAT YTG YTT 3′). PCR amplification was performed as previously reported (15). Agarose gel electrophoresis showed a unique amplification PCR product of about 1,400 bp. PCR products to be sequenced were directly cloned in the phagemid MOSblue system from Amersham (15). DNA fragments were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems 373A apparatus. Since the partial nucleotide sequences of the [Fe] hydrogenase genes from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 and D. vulgaris Hildenborough are highly similar, we used two oligonucleotides, Fe 1 (5′ GGG GGT GAC AGG ATG GTG CAA 3′) and Fe 2 (5′ GAT CGT GGA CAG GTG CTG AC 3′), corresponding to the upstream and downstream nucleotide sequences, respectively, of the [Fe] hydrogenase genes from D. vulgaris Hildenborough, to amplify the D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase genes. PCR was performed directly on chromosomal DNA by using these two facing oligonucleotides. A unique amplification PCR product of about 2,000 bp was directly sequenced as described above. The complete nucleotide sequence coding for the [Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 has been checked by sequencing of the PCR product on both strands by using primer Fe 3 (5′ ACC TCG TGC TGC CCC GGC TGG 3′) for downstream sequencing and primer Fe 4 (5′ CCA GCC GGG GCA GCA CGA GGT 3′) for upstream sequencing (Fig. 1).

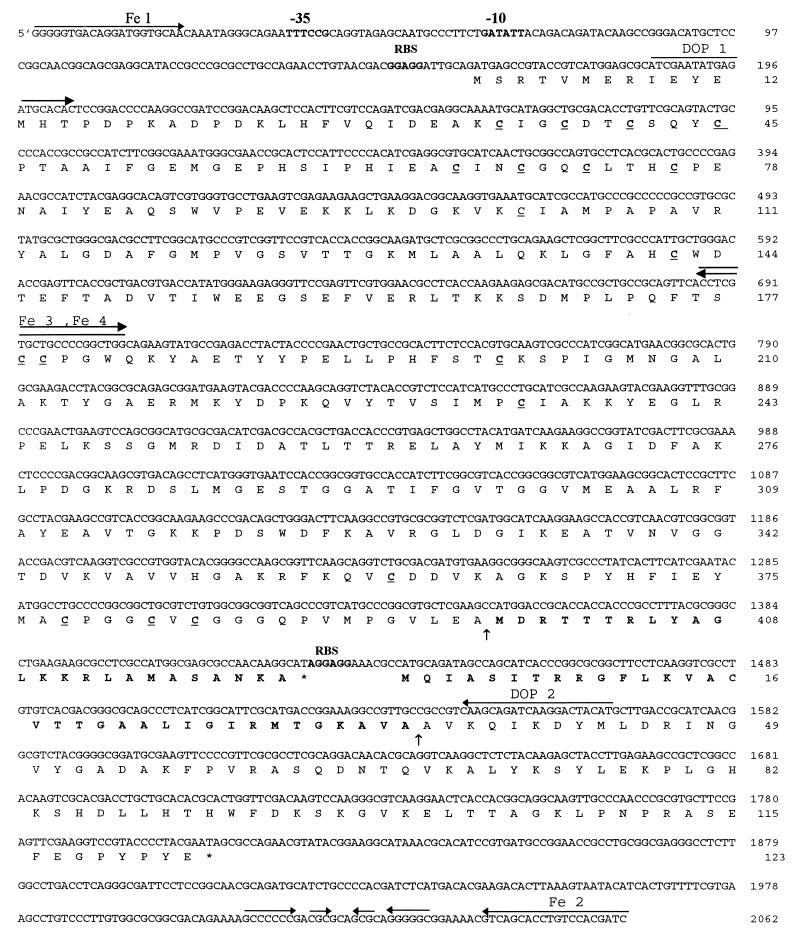

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the hydA and hydB structural genes, encoding the large (46-kDa) and small (13.5-kDa) subunits of the periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase of D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757, respectively. The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence is given in the one-letter amino acid code. Cysteine residues are underlined, and the locations of the cleavage sites on the large and small subunits are shown (↑). Possible sequences serving as the promoter (−10, −35), ribosome-binding sites (RBS), and transcription terminator (→ ←) are indicated. Bold amino acids at the beginning of HydB correspond to the signal sequence. Bold amino acids at the end of HydA correspond to the precursor C-terminal sequence. The sequences of the primers Fe1 and Fe2, drawn from the genomic sequence of the closely related strain D. vulgaris Hildenborough, may not be completely representative of the genomic sequence of D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757. The complete nucleotide sequence has been checked by sequencing of the PCR product on both strands with primer Fe 3 for downstream sequence and primer Fe 4 for upstream sequencing.

Analysis of the nucleotide sequence shows the presence of two contiguous genes, hydA and hydB (Fig. 1). The hydA gene, of 1,263 bp, coding for the large subunit is located between ATG at position 161 and TAG at position 1424. The hydB gene, of 369 bp, corresponding to the small subunit starts at ATG position 1438 and terminates at TAG position 1807. The two genes are very close together, with only 11 bp between them. A putative promoter region consisting of a −10 sequence (GATATT) and a −35 sequence (TTTCCG) are located 92 to 133 bp upstream from the ATG of hydA. A first ribosome binding site (GGAGG) is located 7 bp upstream from the ATG of hydA, and a second canonical ribosome binding site (AGGAGG) is also located 7 bp upstream from ATG of hydB, overlapping the TAG stop codon of hydA. The two genes are probably expressed as a single transcriptional unit. An inverted repeated sequence with a ΔG of −13 kcal mol−1 is situated 200 to 250 bp downstream from hydB. It might constitute a transcription terminator.

The hydA nucleotide sequence encodes a polypeptide of 420 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 45,820 Da, and the hydB gene encodes a polypeptide of 122 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 13,493 Da, excluding the N-formylmethionine. The amino acid sequence of the N-terminal extremity of the small subunit of D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase lacks a peptide of 34 amino acids encoded by the gene for the small subunit (13), indicating that the N-terminal alanine residue of the mature small subunit (calculated molecular mass, 10,135 Da) is preceded by a potential signal sequence. This N-terminal signal peptide contains the conserved feature (RRXFXK) reported for other Desulfovibrio species [Fe] hydrogenases (40).

When the nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding the [Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 was compared with that of the well-characterized hydrogenase from D. vulgaris Hildenborough (37), only 14 of 1,649 nucleotides were found to be different, indicating that the two strains are closely related, in agreement with the data based on the analysis of 16S rRNA (6). Furthermore, these differences always affect the third letter of the codons, leading to total identity between both pairs of amino acid sequences (37) (see below). As reported for D. vulgaris Hildenborough [Fe] hydrogenase, the three iron-sulfur clusters known to be present in D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 [Fe] hydrogenase (13) must all coordinate to large-subunit cysteine residues, since the mature small subunit lacks cysteine.

Mass spectrometric data.

[Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 was purified and S-carboxymethylated hydrogenase was prepared as described previously (13). In this study, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry was used to measure the masses of the subunits of [Fe] hydrogenase with samples of native and S-carboxymethylated protein. The sample of native [Fe] hydrogenase (21 μM) was obtained after careful dialysis against distilled water. Lyophilized S-carboxymethylated [Fe] hydrogenase (4 nmol) was dissolved in 80 μl of acetic acid and diluted with 200 μl of distilled water to a solution concentration of 14 μM. A 20-mg/ml sinapinic acid solution in H2O–0.1% trifluoroacetate/acetonitrile (60:40) was freshly prepared prior to experimentation. Then 1.4 μl of a 1:1 mixture of either native [Fe] hydrogenase or S-carboxymethylated hydrogenase solution and sinapinic acid solution was applied to the sample plate and the droplets were allowed to dry at room temperature before insertion. External mass calibration was provided by the [M+H]+ and [M+2H]2+ ions of apo-myoglobin (16,951.5 and 8,476.3 Da, respectively). Mass spectrometry was performed with a Voyager DE-RP (Perspective Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with an XY multisample probe. Ionization was accomplished with a 337-nm beam from a nitrogen laser with 3-ns-wide pulses. All data were acquired at 25 kV of acceleration potential in the positive-ion mode with the linear detector.

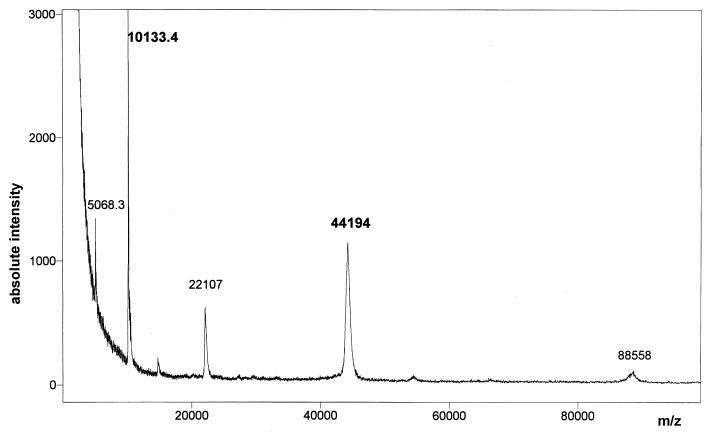

The measured mass from the singly charged ion of the S-carboxymethylated small subunit was found to be 10,133.4 Da (Fig. 2), in excellent agreement with the value of 10,135 Da expected from the predicted amino acid sequence of the mature small subunit. The mass spectrum also displays the doubly charged ion of the small subunit, corresponding to a mass of 5,068.3 Da. When measurements were made on native [Fe] hydrogenase (data not shown), the value for the small subunit (10,133.7 Da) was found to be identical to that obtained with the small subunit of the S-carboxymethylated hydrogenase, in agreement with the lack of cysteine residues and iron-sulfur clusters in this subunit. The measured mass for the singly charged ion of the S-carboxymethylated large subunit of D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase was found to be 44,194 Da (Fig. 2). The MALDI-TOF spectrum showed two other charged species related to [M+H]2+ and [2M+H]+ ions, with corresponding masses of 22,107 and 88,558 Da, respectively. The mass of the large-subunit apoprotein of [Fe] hydrogenase can be deduced from the mass of the S-carboxymethylated large subunit, taking account of the presence of 18 alkylated cysteine residues within the protein. A mass of 43,149 Da is then obtained for the large subunit by subtracting the mass of 18 -CH2-COOH alkyl groups, each with a calculated mass of 59 Da, and adding the mass of 18 H atoms.

FIG. 2.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of the S-carboxymethylated [Fe] hydrogenase of D. desulfuricans. The measured molecular masses of the S-carboxymethylated small and large subunits are 10,133.4 and 44,194 Da, respectively.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry measurements made on native [Fe] hydrogenase yielded a mass of 43,316 Da for the large subunit (data not shown), a value which is slightly higher than that obtained for the large-subunit apoprotein (43,149 Da). This higher molecular mass could arise from intermediate protein species which appear during decomposition of the iron-sulfur clusters bound to the native large subunit. Mass spectrometric analyses on [Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 indicated that the measured molecular mass of the large-subunit apoprotein (43,149 Da) was smaller than the expected molecular mass based on the gene-deduced amino acid sequence (45,820 Da). The difference (2,671 Da) suggests the occurrence of carboxy-terminal processing of a precursor form of the large subunit, since previous studies have shown that the native large subunit lacks an N-terminal signal sequence (13).

C-terminal sequence of the large subunit of D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 [Fe] hydrogenase.

The C-terminal sequence of the large subunit of the S-carboxymethylated [Fe] hydrogenase of D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 was deduced by digestion with carboxypeptidase Y. A time course analysis of carboxypeptidase Y digestion revealed only alanine after 15 min. With increasing times of incubation, other residues, including glutamic acid, leucine, valine, and glycine, were released in addition to alanine. The ratio of amino acids released after a 2-h digestion was Ala (0.96), Glu (0.33), Leu (0.20), Val (0.16), and Gly (0.10). These data are consistent with the following C-terminal sequence -Gly-Val-Leu-Glu-Ala.

This amino acid sequence differs from the C-terminal sequence encoded by the gene for the large subunit (-Ser-Ala-Asn-Lys-Ala421) (Fig. 1). The data demonstrated that the carboxyl end of the mature large subunit was 24 amino acids shorter than the amino acid sequence deduced from the gene and that the C-terminal cleavage occurred after Ala397 (Fig. 3). It follows that the large subunit of [Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 is synthesized as a larger precursor protein from which the mature large subunit is derived by proteolytic cleavage of a C-terminal peptide. Hence, the mature large subunit is 2,668 Da smaller than the precursor form of the protein (45,820 Da) calculated from the gene-deduced amino acid sequence. This gives a value of 43,152 Da, in good agreement with the molecular mass measured by mass spectrometry for the mature large subunit (43,149 Da).

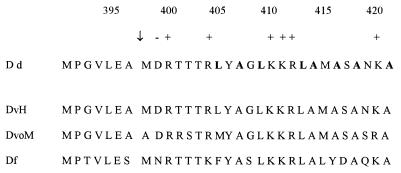

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the gene-deduced C-terminal sequence of the large subunit of the dimeric [Fe] hydrogenases from Desulfovibrio species. Dd, [Fe] hydrogenase from D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 (this work); hydrophobic residues (alanine and leucine) are in boldface type, and charges are as indicated. DvH, [Fe] hydrogenase from D. vulgaris Hildenborough (37). DvoM, [Fe] hydrogenase from D. vulgaris subsp. oxamicus Monticello (38). Df, [Fe] hydrogenase from D. fructosovorans (5). The position of the putative processing site is indicated (↓).

The precursor C-terminal sequence of the D. desulfuricans [Fe] hydrogenase large subunit is highly basic and exhibits a high percentage of hydrophobic (alanine and leucine) and hydroxylated amino acids (Fig. 3). These properties are shared by mitochondrial targeting NH2-terminal sequences, which display, in contrast to the precursor C-terminal sequence, a regular spacing of the positive charges, allowing the formation of an amphiphilic helix (26, 36). Based on these data and a comparative analysis of the gene sequences of the large subunits of other dimeric [Fe] hydrogenases from Desulfovibrio species which exhibit a high degree of similarity (Fig. 3), it can be postulated that the large subunits of these enzymes undergo C-terminal processing involving cleavage at a site analogous to Ala397 of D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 hydrogenase (Fig. 3). As with the NH2-terminal signal peptides of small subunits of [Fe] and [NiFe] hydrogenases (40) and cytochrome c3 (15), the peptidase cleavage site would occur after an alanine residue, except for the putative C-terminal peptide of Desulfovibrio fructosovorans [Fe] hydrogenase, which exhibits a cleavage site located after a serine residue (5).

The significance of the C-terminal processing of the large subunit of [Fe] hydrogenase of Desulfovibrio species remains to be elucidated. It was demonstrated that carboxy-terminal processing of the large subunit of [NiFe] hydrogenases is associated with the incorporation of nickel into the protein, which is a prerequisite for translocation of the hydrogenase across the cytoplasmic membrane (25). For the dimeric [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio species, it is likely that carboxy-terminal processing of the large subunit is not involved in the binding of the H cluster to the protein, since comparative analysis of gene sequence indicates that the monomeric [Fe] hydrogenases from clostridia which are correctly matured lack the corresponding sequence encoding the precursor C-terminal extension present in the large subunit of dimeric hydrogenases (10, 16). Carboxy-terminal processing of precursor proteins destined to be exported to the periplasm or transported into organelles has been reported in a few cases (7, 17). Several observations indicate that the COOH-terminal processing of the dimeric [Fe] hydrogenase large subunit could be involved in the export of the protein to the periplasm: (i) cytoplasmic monomeric [Fe] hydrogenases from clostridia lack the gene sequence coding for the C-terminal extension found in the precursor form of the large subunit of dimeric [Fe] hydrogenase; (ii) the large subunit, in contrast to the small subunit, lacks an NH2-terminal signal peptide; and (iii) the C-terminal extension has some characteristics in common with the import NH2-terminal signal sequences which target proteins to inner compartments of eukaryotic organelles such as the mitochondrial matrix (26, 30).

The NH2-terminal sequences of the small subunits of periplasmic or membrane-bound [Fe] or [NiFe] hydrogenases possess a strictly conserved motif (RRXFXK). This class of particular signal sequences has been extended to twin-arginine signal peptides that are found on precursors of bacterial periplasmic proteins binding various types of redox cofactors (3). Recently, a novel Sec-independent export system that may be used for the translocation of these folded proteins, including [NiFe] hydrogenase, has been identified in E. coli (4, 28). However, this export system has not been shown to function for the translocation of [Fe] hydrogenase, since such an enzyme is not present in this bacterium. Since the catalytic subunits of [Fe] hydrogenases (binding the H cluster) and [NiFe] hydrogenases (binding the Ni-Fe cluster) lack an NH2-terminal signal sequence, it was notably postulated that the single signal peptide of the small subunit containing the double-arginine motif could mediate the export of both subunits to the periplasm (3, 40). The data reported here indicate that the periplasmic [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio species undergoes a C-terminal processing of its catalytic subunit, as is the case for [NiFe]-type hydrogenase. However, the biological significance of the two processes appears to be different: this processing is associated with the incorporation of nickel into the large subunit of [NiFe] hydrogenase, whereas it might be involved directly or indirectly in the export of the enzyme to the periplasm in the case of [Fe] hydrogenase.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge J. Bonicel for mass spectrometric analyses and N. Zylber for amino acid analyses. We are also indebted to V. Méjean for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M W W. The structure and mechanism of iron-hydrogenases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1020:115–145. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albracht S P J. Nickel hydrogenases: in search for the active site. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1188:167–204. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berks B C. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:393–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogsch E G, Sargent F, Stanley N R, Berks B C, Robinson C, Palmer T. An essential component of a novel bacterial protein export system with homologues in plastids and mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18003–18006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casalot L, Hatchikian E C, Forget N, de Philip P, Dermoun Z, Bélaich J-P, Rousset M. Molecular study and partial characterization of iron-only hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Anaerobe. 1998;4:45–55. doi: 10.1006/anae.1997.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereux R, He S-H, Doyle C L, Orkland S, Stahl D A, LeGall J, Whitman W B. Diversity and origin of Desulfovibrio species: phylogenetic definition of a family. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3609–3619. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3609-3619.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diner B A, Ries D F, Cohen B N, Metz J G. COOH-terminal processing of polypeptide D1 of the photosystem II reaction center of Scenedesmus obliquus is necessary for the assembly of the oxygen-evolving complex. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8972–8980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauque G, Peck H D, Jr, Moura J J G, Huynh B H, Berlier Y, DerVartanian D V, Teixeira M, Przybyla A E, Lespinat P A, Moura I, LeGall J. The three classes of hydrogenases from sulfate-reducing bacteria of the genus Desulfovibrio. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1988;54:299–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gollin D J, Mortenson L E, Robson R L. Carboxyl-terminal processing may be essential for production of active NiFe hydrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:371–375. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80809-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorwa M-F, Croux C, Soucaille P. Molecular characterization and transcriptional analysis of the putative hydrogenase gene of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2668–2675. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2668-2675.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grande H J, Dunham W R, Averill B, Van Dijk C, Sands R H. Electron paramagnetic resonance and other properties of hydrogenases isolated from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (strain Hildenborough) and Megasphaera elsdenii. Eur J Biochem. 1983;136:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagen W R, Van Berkel-Arts A, Kruse-Wolters K M, Voordouw G, Veeger C. The iron-sulfur composition of the active site of hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) deduced from its subunit structure and total iron-sulfur content. FEBS Lett. 1986;203:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatchikian E C, Forget N, Fernandez V M, Williams R, Cammack R. Further characterization of the [Fe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 7757. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higuchi Y, Yagi T, Yasuoka N. Unusual ligand structure in Ni-Fe active center and a additional Mg site in hydrogenase revealed by high resolution X-ray structure analysis. Structure. 1997;5:1671–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magro V, Pieulle L, Forget N, Guigliarelli B, Petillot Y, Hatchikian E C. Further characterization of the two tetraheme cytochromes c3 from Desulfovibrio africanus: nucleotide sequences, EPR spectroscopy and biological activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1342:149–163. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer J, Gagnon J. Primary structure of hydrogenase I from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9697–9704. doi: 10.1021/bi00104a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagasawa H, Sakagami Y, Suzuki A, Suzuki H, Hara H, Hirota Y. Determination of the cleavage site involved in C-terminal processing of penicillin-binding protein 3 of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5890–5893. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5890-5893.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolet Y, Piras C, Legrand P, Hatchikian E C, Fontecilla-Camps J C. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans iron hydrogenase: the structure shows unusual coordination to an active site Fe binuclear center. Structure. 1999;7:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nivière V, Bernadac A, Forget N, Fernandez V M, Hatchikian E C. Localization of hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio gigas cells. Arch Microbiol. 1990;155:579–586. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nivière V, Wong S-L, Voordouw G. Site-directed mutagenesis of the hydrogenase signal peptide consensus box prevents export of a β-lactamase fusion protein. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2173–2183. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-10-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odom J M, Peck H D., Jr Hydrogenase, electron transfer proteins, and energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:551–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patil D S, Moura J J G, He S H, Teixeira M, Prickril B C, DerVartanian D V, Peck Jr H D, LeGall J, Huynh B-H. EPR-detectable redox centers of the periplasmic hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18732–18738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierik A J, Hagen W R, Redeker J S, Wolbert R B G, Boresma M, Verhagen M F J M, Grande H J, Veeger C, Mutsaers P H A, Sands R H, Dunham W R. Redox properties of the iron-sulfur clusters in activated Fe-hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Przybyla A E, Robbins J, Menon N, Peck H D., Jr Structure-function relationships among the nickel-containing hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:109–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigue A, Boxer D H, Mandrand-Berthelot M A, Wu L-F. Requirement for nickel of the transmembrane translocation of NiFe-hydrogenase 2 in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00788-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roise D, Horvath S J, Tomich J M, Richards J H, Schatz G. A chemically synthesized pre-sequence of an imported mitochondrial protein can form an amphiphilic helix and perturb natural and artificial phospholipid bilayers. EMBO J. 1986;5:1327–1334. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossman R, Sauter M, Lottspeich F, Böck A. Maturation of the large subunit (HycE) of hydrogenase 3 of Escherichia coli requires nickel incorporation followed by C-terminal processing at Arg537. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santini C-L, Ize B, Chanal A, Müller M, Giordano G, Wu L-F. A novel Sec-independent periplasmic protein translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1998;17:101–112. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders G F, Campbell L L, Postgate J R. Base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid of sulfate-reducing bacteria deduced from buoyant density measurement in cesium chloride. J Bacteriol. 1964;87:1073–1078. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.5.1073-1078.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schatz G, Dobberstein B. Common principles of protein translocation across membranes. Science. 1996;271:1519–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramani S. Convergence of model systems for peroxisome biogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:513–518. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Westen H, Mayhew S G, Veeger C. Separation of hydrogenase from intact cells of Desulfovibrio vulgaris. FEBS Lett. 1978;86:122–126. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Dongen W, Hagen W R, Van den Berg W, Veeger C. Evidence for an unusual mechanism of membrane translocation of the periplasmic hydrogenase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough), as derived from expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;50:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volbeda A, Piras C, Charon M-H, Hatchikian E C, Frey M, Fontecilla-Camps J C. Crystal structure of the nickel-iron hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature. 1995;373:580–587. doi: 10.1038/373580a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volbeda A, Garcin E, Piras C, de Lacey A I, Fernandez V M, Hatchikian E C, Frey M, Fontecilla Camps J C. Structure of the [NiFe] hydrogenase active site: evidence for biological uncommon Fe ligands. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:12989–12996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Heijne G. Mitochondrial targeting sequences may form amphiphilic helices. EMBO J. 1986;5:1335–1342. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voordouw G, Brenner S. Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voordouw G, Strang J D, Wilson F R. Organization of the genes encoding [Fe] hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio vulgaris subsp. oxamicus Monticello. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3881–3889. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3881-3889.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voordouw G. Hydrogenase genes in Desulfovibrio. In: Bélaich J P, Bruschi M, Garcia J L, editors. Microbiology and biochemistry of strict anaerobes involved in interspecies hydrogen transfer. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voordouw G. Evolution of hydrogenase genes. Adv Inorg Chem. 1992;38:397–422. [Google Scholar]