Abstract

Background

Despite the implementation of essential newborn care (ENC) by the World Health Organization, knowledge gaps among postpartum women persist. Inappropriate breastfeeding practices and lack of knowledge regarding ENC among mothers has resulted in higher neonatal mortality.

Purpose

Our study focused on evaluating the effectiveness of flip-chart assisted postpartum maternal education in improving ENC knowledge and skills.

Material and Methods

A single blind parallel randomized controlled trial was carried out with 120 primigravidae. Participants were allocated to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG) by block randomization. A pretested validated questionnaire was administered to participants in both groups within 24 h post-delivery. Women in the IG were provided flip-chart assisted education regarding ENC approximately 24 h post-delivery. Women in both groups received verbal advice on ENC from the postnatal ward nurses, as per the existing hospital policy. ENC skills were observed in all participants in postnatal wards by independent observers. 6 months later, knowledge retention was assessed and analyzed in both groups.

Results

Antenatal education remained at 32% among all postnatal women. Postnatal flip-chart-assisted maternal education had a significant impact on ENC skills in the IG (p < 0.01) and precipitated higher knowledge scores at the end of 6 months (p < 0.01) in the IG.

Conclusion for Practice

Flip-chart assisted education soon after delivery had a sustained effect on ENC knowledge and practices that persisted for 6 months post-delivery.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Knowledge retention, Maternal education, Neonatal mortality

Significance

What is already known? Maternal knowledge has a significant role in improving neonatal health. Despite good antenatal coverage, a knowledge gap remains among mothers regarding essential newborn care.

What this study adds? Education with visual aids, like flip-chart assisted maternal education, provided soon after delivery had a sustained effect on essential newborn care knowledge and practices that persisted for 6 months post-delivery.

Introduction

Ending all preventable newborn deaths and reducing neonatal mortality to as low as 12 per 1000 live births by 2030 is the target of the United Nations’ third Sustainable Development Goal (United nations, 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) devised a comprehensive strategy of essential newborn care (ENC) intending to improve the health of newborns through interventions before conception and during the perinatal period (Narayanan et al., 2004). Although WHO has implemented ENC as of 2004, contrary to objectives of the program, inappropriate breastfeeding practices, malnutrition, and lack of knowledge regarding newborn care among mothers has resulted in higher neonatal mortality (Black et al., 2013; Chandhiok et al., 2015; Dongre et al., 2009) (Indian Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) 2017; Patel et al., 2010; UNICEF, 2015). In India, exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) was practiced by only 48.6% of lactating mothers as per National family health survey 3(NFHS-3) as compared to 46.3% in National family health survey 1(NFHS-1) (Chandhiok et al., 2015). In their 2013 systematic review, Haroon et al. concluded that maternal education, either in groups or individually, is an effective means of increasing EBF practice (Haroon et al., 2013).

Knowledge gaps in ENC and deficiencies in skill domains are being observed among health care providers at various levels of the health care system (Malhotra et al., 2014; Pemo et al., 2019). Good antenatal coverage does not necessarily translate into good intranatal/postnatal practices among mothers (Gul et al., 2014). We aimed to assess knowledge of ENC at the time of admission for delivery and study the effectiveness of visual aid like flip chart assisted education soon after delivery in improving ENC knowledge and skills.

Methods

Settings, and Participants

This single-blind parallel randomized controlled trial was conducted at the Government Lady Goshen Hospital (LGH) and the Regional Advanced Paediatric Care Centre (RAPCC), Mangalore, in the district of Dakshina Kannada of coastal South India. These community hospitals are referral centers for tertiary care and are affiliated with Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. The study was conducted from January 2016 to September 2017.

Primigravida women (women who became pregnant for the first time) who vaginally delivered full-term babies weighing 2500 gm or more were included in the immediate postpartum period after informed consent. These women were healthy and could successfully breastfeed their babies. We included primigravida mothers as they do not have prior experience of newborn care. Multipara are excluded since they have cared for newborn babies and uniformity of subjects would be lost. Women with antenatal or postnatal complications were excluded from the study as they may not be able to express their ENC knowledge or take part in flip chart assisted educational intervention in the early neonatal period. Women whose neonates required neonatal intensive care (NICU) were also excluded from the study as these babies may not receive exclusive breastfeeding and the mothers may not be perceptive to knowledge about ENC care when their neonate is sick and in neonatal intensive care unit. The study participants were 120 primigravida women who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Using the software Open Epi version 3.0, the necessary sample size was calculated to be 120 (60 per group), based on a previous study, (Mazumder et al., 2014) with a 95% confidence interval, 80% power, and 10% attrition.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kasturba Medical College Mangalore (IEC KMC MLR 01-16/02) and was enrolled in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2016/04/006840).

Block randomization was carried out to assign study participants into two groups, intervention (IG) and control (CG). Random allocation software version 1.0 was used by an independent person to generate the random sequence with an equal block size of six and 12 total blocks. Allocation concealment was done by handing over the sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelope containing the random sequence and explaining the execution procedure to the resident doctor involved. Socio-demographic details were recorded and a pretested questionnaire was distributed among mothers in both groups within 24 h of delivery. The questionnaire was designed based on ENC as prescribed by WHO to assess the knowledge domain regarding ENC after antenatal care and education by health care providers in the field (WHO, 2002).

Intervention

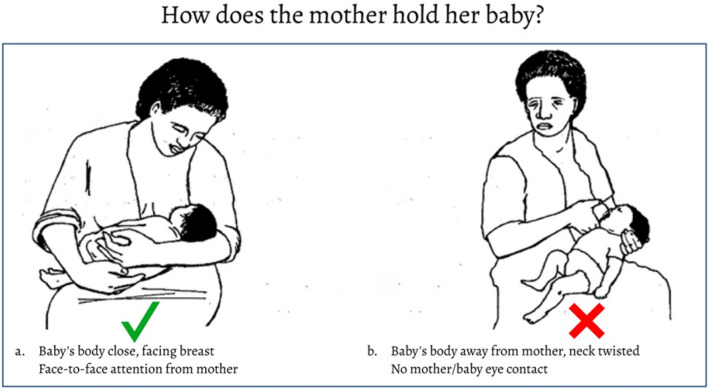

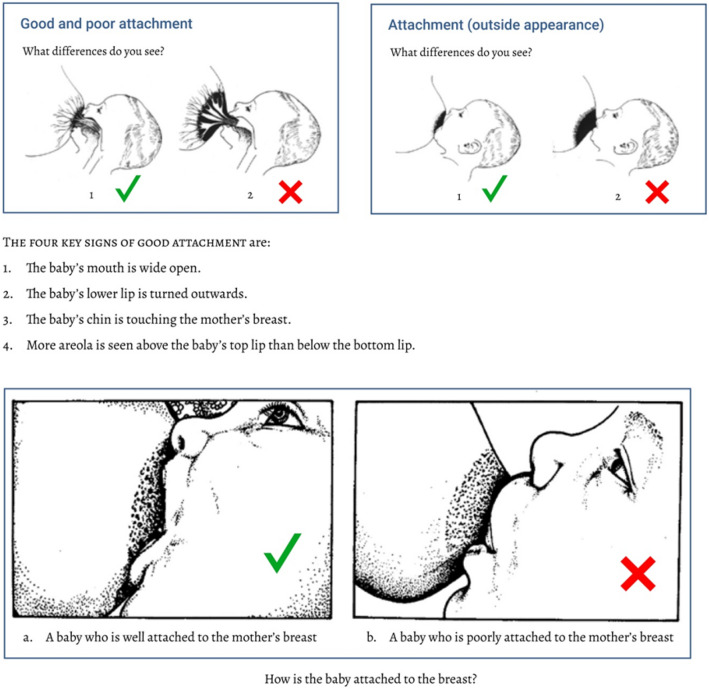

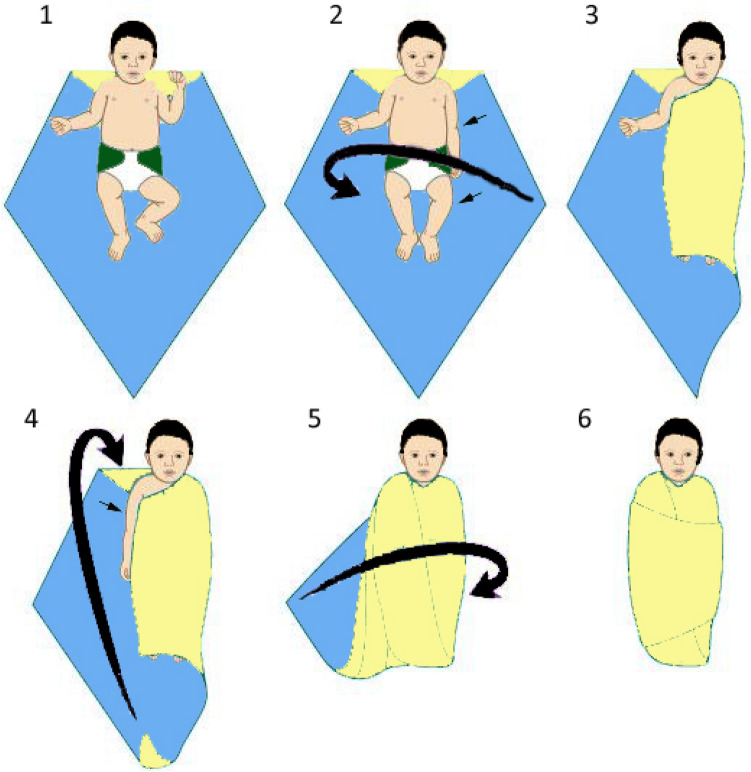

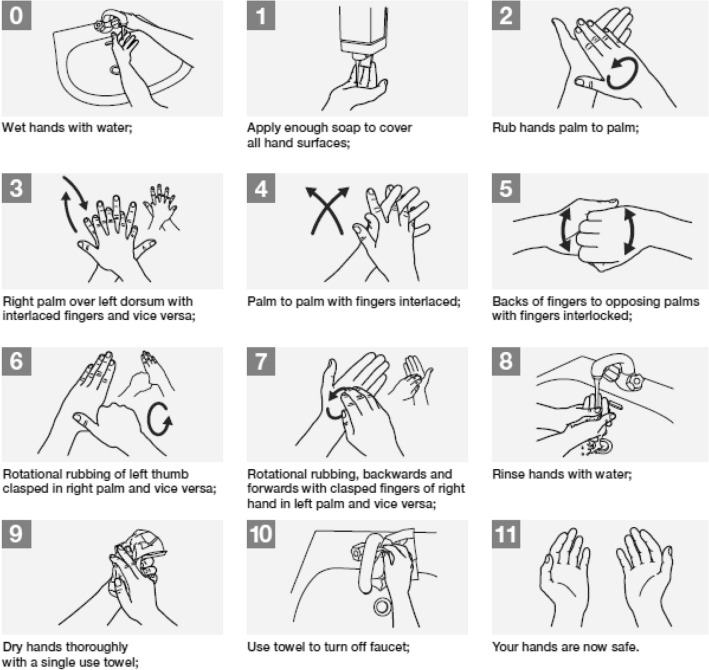

Flip-chart assisted maternal education was provided to the women in the IG after the questionnaires were collected. A flip chart was designed to communicate ENC knowledge and skills. The flip charts demonstrated breastfeeding techniques, newborn care, hygiene practices, and danger signs. Material for the flipcharts were taken from the WHO manual. On ENC (WHO, 2002). The flip charts were approved by the pediatric department and the institutional scientific research committee of Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore. Study tools were prepared in English and then translated into the local language of Kannada. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested using Cronbach’s alpha (0.752). The intervention of flip chart assisted ENC education was carried out by the principal investigator on the second postnatal day. Mothers were explained about the ENC, in their vernacular language with the help of flip charts in small group sessions of 2–3 mothers for 15–20 min duration. Participants in the CG and IG received verbal advice on ENC from the postnatal ward nurses, as per the existing hospital policy.

Outcome Measures

On postnatal day two, participants in both groups were independently observed by trained nurses or resident doctors to assess their breastfeeding skills, thermoregulation, and hand hygiene practices. Observers were trained by the principal investigator and were blinded to study groups. These skill practices were documented separately by each observer and entered in a provided observation catalog. Routine postnatal care and care continuum were maintained in both groups, as per public health directives from the health department.

At the end of 6 months, women in both groups answered the same questionnaire to assess retention of knowledge and skills practiced.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM, Corp., Armonk, NY). Each item on the questionnaire was allotted a particular score, and the median scores were compared using the Mann − Whitney U test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlation coefficients were calculated using Spearman’s correlation. Mothers’ knowledge was compared using a chi-squared test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Participants’ Baseline Knowledge and Practices

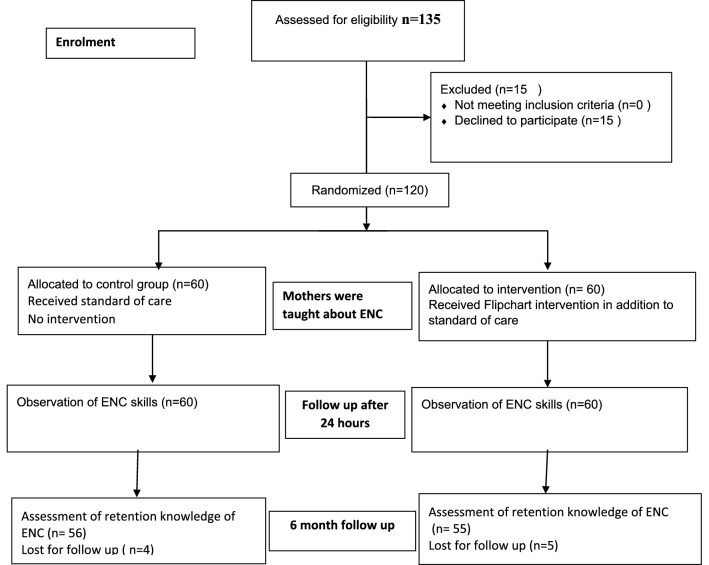

A total of 120 postpartum women were enrolled in the study. They were grouped into either the CG or IG, each with 60 participants, by block randomization (Fig. 1). Both groups had similar demographic characteristics. Out of the 120 mothers in the study, 68.3% had received neither group nor individual education at any time during the antenatal period. Early initiation of breastfeeding (within 1 h) was practiced by only 48.3% and 53.43% of mothers in the CG and IG respectively, despite delivering at the facility.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of the participants through the study. ENC Essential newborn care

Prelacteal feeds were provided by 6.7% of mothers in the CG and 15% of mothers in the IG. There was no statistically significant difference in the baseline ENC knowledge and practices between groups, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline knowledge and practices about essential newborn care between control and intervention groups

| Parameter | CG (n = 60) N (%) |

IG (n = 60) N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colostrum should be given to the baby | |||

| Agree | 58 (96.7) | 60 (100) | |

| Disagree | 2 (3.3) | 0 | 0.15 |

| Intended duration of exclusive breastfeeding | |||

| 3 months | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | |

| 4 months | 2 (3.3) | 4 (6.7) | |

| 5 months | 3 (5) | 2 (3.3) | |

| 6 months | 18 (30) | 20 (33.3) | 0.9 |

| > 6 months | 11 (18.3) | 14 (23.3) | |

| any other | 11 (18.3) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Do not know | 14 (23.3) | 11 (18.3) | |

| Technique of breastfeeding was shown antenatal | |||

| Yes | 36 (60) | 38 (63.3) | |

| No | 24 (40) | 22 (36.7) | 0.7 |

| Technique of breastfeeding was shown by | |||

| Doctor | 3 (8.3) | 4 (10.5) | |

| Nurse | 10 (27.8) | 13 (34.2) | |

| Mother | 13 (36.1) | 12 (31.6) | 0.47 |

| Family elders | 10 (27.8) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Health worker | 0 | 3 (7.9) | |

| Extra diet necessary during lactation | |||

| Agree | 19 (31.7) | 20 (33.3) | |

| Disagree | 41 (68.3) | 40 (66.7) | 0.84 |

| Methods to keep baby warm* | |||

| Keeping in a warm room | 4 (6.7) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Wrapping with a cloth | 47 (78.3) | 43 (71.7) | |

| Covering the head with a cap | 21 (35) | 7 (11.7) | |

| Putting socks and gloves | 6 (10) | 2 (3.3) | 0.07 |

| Any other | 2 (3.3) | 4 (6.7) | |

| Do not know | 10 (16.7) | 14 (23.3) | |

| Handwashing necessary before handling baby | |||

| Agree | 27 (45) | 26 (43) | |

| Disagree | 33 (55) | 34 (57) | 0.24 |

| Frequency of hand wash before handling the baby | |||

| Once a day | 3 (5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Twice a day | 15 (25) | 7 (11.7) | |

| Thrice a day | 19 (31.6) | 21 (35.0) | |

| Every time | 10 (16.7) | 17 (28.3) | 0.30 |

| Any other | 12 (20) | 13 (21.7) | |

| Never | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Danger signs to say a baby is not well * | |||

| Poor suck | 0 | 4 (6.7) | |

| Poor activity | 3 (5) | 7 (11.7) | |

| Jaundice | 1(1.7) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Fever | 7 (11.6) | 13 (21.7) | |

| Hypothermia | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| Breathing difficulty | 3 (5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Convulsions | 1 (1.7) | 0 | |

| Any other | 4 (6.7) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Do not know | 47 (78.3) | 41 (68.3) |

p < o. o5 is statistically significant

CG control group, IG intervention group

*Multiple responses allowed

Primary Outcomes

Outcomes in ENC Skills

In the IG, 60 women received ENC education. Breastfeeding skills, measures of thermoregulation and hygiene practices were demonstrated individually, in-person, and using flip charts. Significant increases in proper breastfeeding techniques, warm care skills, and good hygiene practices were observed among the mothers after education (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of essential newborn care practices of mothers post-intervention in the control and intervention group

| Parameter | IG (n = 60) N (%) |

CG(n = 60) N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding in the proper position | |||

| Yes | 45 (81.8) | 36 (64.3) | 0.03 |

| No | 10 (18.2) | 20 (35.7) | |

| Good latching | |||

| Yes | 46 (83.6) | 32 (57.1) | 0.002 |

| No | 9 (16.4) | ||

| Breast engorgement/cracked nipple | |||

| Yes | 13 (23.6) | 20 (35.7) | 0.16 |

| No | 42 (76.4) | 36 (64.3) | |

| Giving feeds other than breast milk | |||

| Yes | 13 (23.6) | 27 (48.2) | 0.007 |

| No | 42 (76.4) | 29 (51.8) | |

| Wrapping the baby properly with a cloth | |||

| Yes | 50 (90.9) | 45 (80.4) | 0.11 |

| No | 5 (9.1) | 11 (19.6) | |

| Putting a cap and socks | |||

| Yes | 40 (72.7) | 14 (25) | < 0.001 |

| No | 15 (27.3) | 42 (75) | |

| Washing hands before handling the baby | |||

| Yes | 46 (83.6) | 25 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| No | 9 (16.4) | 31 (55.4) | |

| Washing hands before and after eating | |||

| Yes | 43 (78.2) | 49 (87.5) | 0.19 |

| No | 12 (21.8) | 7 (12.5) | |

| Short and clean nails | |||

| Yes | 43 (78.2) | 23 (41.1) | < 0.001 |

| No | 12 (21.8) | 33 (58.9) | |

| Wearing the same dress for 2 days in a row | |||

| Yes | 20 (36.4) | 39 (69.6) | < 0.001 |

| No | 35 (63.6) | 17 (30.4) | |

p value < 0.05 is statistically significant

CG control group, IG intervention group

Outcomes in Knowledge Retention After 6 Months

At the end of 6 months, EBF, warm care practices, and maintaining hand hygiene was higher in the IG (Table 3). The ability to recognize danger signs in the baby was also significantly higher in the IG (Table 3). The incidence of illness among infants was significantly less in the IG; only 24.1% in the IG had febrile illness as opposed to 61.8% of the CG. The knowledge domain score was calculated as the median score based on the interquartile range. The post-intervention knowledge domain score at 6 months was higher in the IG (14, as opposed to 6 in the CG), suggesting the immediate postpartum period as ideal timing for education (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of essential newborn care knowledge 6 month following the intervention in control and intervention groups

| Parameter | CG (n = 56) N (%) |

IG (n = 55) N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colostrum should be given to the baby | |||

| Agree | 56 (100) | 55 (100) | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding | |||

| 3 months | 3 (5.4) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| 4 months | 2 (3.6) | 0 | |

| 5 months | 5 (8.9) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 6 months | 17 (30.4) | 47 (85.5) | |

| > 6 months | 14 (25) | 5 (9.1) | |

| any other | 12 (21.40 | 2 (3.6) | |

| Do not know | 0 | 0 | |

| Extra diet necessary for lactation | |||

| Agree | 16 (28.6) | 52 (94.5) | < 0.001 |

| Disagree | 40 (71.4) | 3 (5.5) | |

| Methods to keep baby warm* | |||

| Keeping in a warm room | 5 (8.9) | 26 (47.3) | < 0.001 |

| Wrapping with a cloth | 49 (87.5) | 54 (98.2) | |

| Covering the head with a cap | 21 (37.5) | 55 (100) | |

| Putting socks and gloves | 8 (14.3) | 42 (76.4) | |

| Any other | 1 (1.8) | 5 (9.1) | |

| Do not know | 3 (5.3) | 0 | |

| Handwashing necessary before handling baby | |||

| Agree | 24 (42.8) | 48 (87.2) | 0.01 |

| Disagree | 32(57.2) | 7 (12.8) | |

| Frequency of hand wash before handling the baby | |||

| Once a day | 2 (3.6) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Twice a day | 18 (32.1) | 0 | |

| Thrice a day | 17 (30.4) | 9 (16.4) | |

| Every time | 9 (16.1) | 46 (83.6) | |

| Any other | 10 (17.8) | 0 | |

| Never | 0 | 0 | |

| Danger signs to say a baby is not well * | |||

| Poor suck | 0 | 37 (67.3) | < 0.001 |

| Poor activity | 5 (8.9) | 50 (90.9) | |

| Jaundice | 0 | 44 (80) | |

| Fever | 9 (16.1) | 52 (94.5) | |

| Hypothermia | 0 | 19 (34.5) | |

| Breathing difficulty | 2 (3.6) | 50 (90.9) | |

| Convulsions | 0 | 34 (61.8) | |

| Any other | 2 (3.6) | 0 | |

| Do not know | 43 (76.7) | 0 |

p < 0.05 is statistically significant

CG control group, IG intervention group

Table 4.

Knowledge domain scores pre-intervention and 6 months post-intervention

| Timeline | Median score (IQR) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | ||

| Pre-intervention | 7 (5.2–8.7) | 7 (5–9) | 0.40 |

| 6-month post intervention | 14 (13–14) | 6 (4–8) | < 0.001 |

p value < 0.05 is statistically significant

IQR Inter quartile range

Discussion

Despite several programs and multipronged approaches, EBF for 6 months, and “good ENC practices” were not universal (Meshram et al., 2019). The present study was intended to assess whether providing education to women immediately after delivery had a better and longstanding impact on ENC knowledge and skills. In the study area, which has a female literacy rate of 84.13%, (Indian Population Census, 2020) only 32% of expectant mothers had received antenatal education despite 97% antenatal coverage. A low percentage of breastfeeding initiation within 1 h (48.3% in the CG, 53.4% in the IG) and the introduction of prelacteal feeds were indicative of the ineffectiveness of counseling during antenatal visits, with potentially serious consequences. Awasthi et al. found very low rates of EBF and a lack of proper knowledge on complementary feeding to be contributors to severe acute malnutrition in northern India (Awasthi et al., 2019). A study by Madhu et al. in South India reported practices such as discarding of colostrum and improper complementary feeding practices; the researchers emphasized the need for breastfeeding educational programs during antenatal and postnatal check-ups (Madhu et al., 2009). In the present study, low knowledge domains regarding ENC among all mothers pre-intervention indicated either ineffective antenatal education or poor receptiveness among expectant mothers. There was also lack of uniformity in the persons imparting the knowledge on ENC in the antenatal period in both groups. Their knowledge on ENC is variable and proportional to prior training and experience. Mothers and family elders providing the knowledge on newborn care may not cover all aspects of ENC. Their advice may be influenced by their cultural and religious customs (Pemo et al, 2019).

Improved breastfeeding practices, hygiene skills, and temperature maintenance after the educational intervention reflected enhanced receptiveness arising out of need. This significant behavioral change needs to be leveraged for better neonatal care. The loss of knowledge and skill domains after antenatal education is the consequence of a long interval between education and practical application in the postnatal period. In contrast, knowledge application and skill practices happened instantaneously after education in the IG in the present study, which resulted in higher scores after 6 months. Lower scores in the knowledge and skill domains in the CG despite the care continuum indicated the ineffectiveness of healthcare workers in caring for lactating mothers. Advice that was not reflective of the expectations and experiences of primiparous women caused anxiety among mothers and subsequent failure of lactation and EBF (Malouf et al., 2019).

The technique of breastfeeding was described verbally in the immediate postnatal period by similar personnel for both groups as per our hospital protocol. The number of subjects who were informed about the breast feeding technique was also similar in both groups. However with our intervention we demonstrated significantly higher EBF in the IG, compared with the CG at 6 months of age of their infants. The timing of intervention, the expertise and training of personnel imparting the education and the tools provided for communication contributed significantly to the mothers knowledge and skills on ENC.

A cluster randomized controlled trial in Ghana involved an intervention in which health care providers were trained to use the continuum of care cards as an educational tool to provide primary postnatal care to women, either in a health care facility or through home visits. The intervention translated into a better quality of care (Okawa et al., 2019). Higher rates of EBF were due to higher confidence levels and good dietary practices adopted post-intervention (Okawa et al., 2019).Strengthening efforts to enhance mothers’ self-confidence is essential in encouraging EBF, especially in countries with low EBF rates (Adhisivam et al., 2017; Chandhiok et al., 2015; Haroon et al., 2013; Opadeyi et al. 2019; Victora et al., 2016; Tsegaye et al., 2019). The present study established that the best breastfeeding practices with long term benefits can be achieved by reinforcing education on ENC soon after delivery.

Knowledge of danger signs in newborns considerably increases mothers’ health-seeking behavior, thereby increasing the chances of child survival. Maternal knowledge of danger signs in the IG was significantly higher 6 months post-intervention (Table 3). Thus, the present study established that the immediate postpartum period is the ideal time for maternal education to achieve good breastfeeding, thermal care, and hygiene practices, followed by EBF for 6 months, for overall improvement in neonate and infant health. The educational intervention followed by the practical demonstration and immediate practice on their own neonate had a significant impact compared to the routine verbal counselling by the ward nurses.

Limitations

The place of intervention was urban. Studies involving childbirth in rural regions of India, may be required to generalize the applicability of this intervention. Under ordinary circumstances ENC education is provided by healthcare workers like ward nurses and lactation counsellors. They could be trained to give the flip-chart aided education under the intervention. We have not collected the information about expectations of primiparous women regarding ENC education. Further studies on impact of educating mothers with previous children, mothers with multiple pregnancies, and with neonates who required intensive care in the early neonatal period are recommended.

Conclusion for Practice

Significant increases in proper breastfeeding techniques, warm care skills, and good hygiene practices were observed among mothers after receiving postnatal flip-chart assisted education. Furthermore, compared with the control group, the intervention group demonstrated an improved ability to recognize danger signs in newborns and had reduced rates of illness in early infancy. Maternal education soon after delivery had a sustained effect on ENC knowledge and practices that persisted for 6 months post-intervention. Mothers are perceptive to receive information about caring for their newborn immediately after childbirth. Demonstration of ENC skills by the health care provider and practice on their newborn under supervision helps in knowledge retention. Further irrespective of the number of antenatal visits, all mothers will have their delivery in a healthcare facility. The peripartum period is available to healthcare providers for educating mothers on ENC. Training these personnel on ENC will maintain uniformity of imparting knowledge and skills regarding ENC. Mothers will also have an opportunity to clarify their doubts or difficulties after practicing ENC on their neonates. Thus, education regarding ENC provided during this period is an effective intervention for lactating mothers to improve the care of their infants.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support and time provided by the community and respondents for participation in this study. The authors are also grateful to the staff of District Community Hospital for facilitating the ability for the research to be conducted smoothly.

Appendix 1 (Questionnaire)

Questionnaire to Compare the Baseline Knowledge About Essential Newborn Care Between Control and Intervention Groups

| 1 | Did you receive education regarding new born care during your antenatal visits? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| 2 | Do you feel colostrum should be given to the baby? |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 3 | When did you initiate breast feeding your baby ? |

| Within half an hour | |

| Between half to 1 h | |

| Between one to 2 h | |

| Beyond 2 h | |

| 4 | What did you feed the baby ? |

| Direct breast feed | |

| Formula feeds | |

| Water | |

| Honey | |

| Both breast feed and formula feed | |

| Any other | |

| 5 | How long you intend to exclusive breastfeed ? |

| 3 months | |

| 4 months | |

| 5 months | |

| 6 months | |

| > 6 months | |

| Do not know | |

| 7 | Were you shown the technique of breastfeeding during antenatal visits ? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| 8 | If answer to question 7 is yes, who showed the technique of breastfeeding ? |

| Doctor | |

| Nurse | |

| Mother | |

| Family elders | |

| Health worker | |

| 9 | Do you feel extra diet necessary during lactation ? |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 10 | How will you keep your baby warm (choose whichever is applicable)? |

| Keeping in a warm room | |

| Wrapping with a cloth | |

| Covering the head with a cap | |

| Putting socks and gloves | |

| Any other | |

| Do not know | |

| 11 | Handwashing is necessary before handling baby |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 12 | How frequently do you wash hands before handling the baby? |

| Once a day | |

| Twice a day | |

| Thrice a day | |

| Every time | |

| Never | |

| Any other | |

| 13 | What are the danger signs to say baby is not well? |

| Poor suck | |

| Poor activity | |

| Jaundice | |

| Fever | |

| Hypothermia | |

| Breathing difficulty | |

| Convulsions | |

| Any other | |

| Do not know |

Questionnaire to Compare of Essential Newborn Care Knowledge and Practices 6 month Following the Intervention

| 1 | Do you feel colostrum should be given to the baby? |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 2 | How long did you exclusively breastfeed? |

| 3 months | |

| 4 months | |

| 5 months | |

| 6 months | |

| > 6 months | |

| Do not know | |

| 3 | Do you feel extra diet necessary during lactation? |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 4 | How will you keep your baby warm (choose whichever is applicable)? |

| Keeping in a warm room | |

| Wrapping with a cloth | |

| Covering the head with a cap | |

| Putting socks and gloves | |

| Any other | |

| Do not know | |

| 5 | Handwashing is necessary before handling baby |

| Agree | |

| Disagree | |

| 6 | How frequently do you wash hands before handling the baby? |

| Once a day | |

| Twice a day | |

| Thrice a day | |

| Every time | |

| Never | |

| Any other | |

| 7 | What are the danger signs to say baby is not well? |

| Poor suck | |

| Poor activity | |

| Jaundice | |

| Fever | |

| Hypothermia | |

| Breathing difficulty | |

| Convulsions | |

| Any other | |

| Do not know | |

| 8 | Did your infant got any febrile illness in past 6 months? |

| Yes | |

| No | |

| 9 | If answer to question 8 is yes, mention the number of episodes |

Appendix 2 (Flip Charts)

Flip Charts

Breast Feeding

Advantages of Breastfeeding

Position of Breastfeeding

Attachment to the Breast

Care of Skin and Eyes

To use warm water

To test the water temperature before starting

To use only clean water on the face and not to use soap

To gently wipe each eye clean with the corner of a clean cloth, using a new corner for each eye, starting near the nose and wiping outward

To dry each part thoroughly after washing it

To separate the skin folds to look for any rashes

To thoroughly dry inside the skin folds

To look for signs of eye or umbilical infection

To wrap the baby well

Warm Care

Swaddling of Baby

Use Caps, Mitten and Socks

Hand Wash

Hand Wash Before Handling the Baby

How to Hand Wash ?

Danger Signs

|

Poor suck Feeding difficulties |

| Poor activity |

| Jaundice |

| Fever |

| Hypothermia |

| Breathing difficulty |

| Convulsions |

Author Contributions

Dr SE: Concept, data collection, manuscript writing, critical review. Dr BSB: concept, design, supervision of data collection, critical review of manuscript. Dr SSR: Design, data analysis, manuscript drafting, literature search, critical review. Dr VV: Design, data analysis, manuscript drafting. Dr NK: concept, design, guidance and supervision of data collection, manuscript draft and critical review.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Data Availability

Data can be made available on request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kasturba Medical College Mangalore (IEC KMC MLR 01-16/02) and was enrolled in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2016/04/006840).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Swathi Eluri, Email: dr.swathieluri@gmail.com.

B. Shantharam Baliga, Email: drbsbaliga@gmail.com.

Suchetha S. Rao, Email: suchetha.rao@manipal.edu

V. Vinayagamoorthy, Email: drvinayagamoorthy@gmail.com

Nutan Kamath, Email: nutan.kamath@manipal.edu.

References

- Adhisivam B, Vishnu Bhat B, Poorna R, Thulasingam M, Pournami F, Joy R. Postnatal counseling on exclusive breastfeeding using video–experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital, South India. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2017;30(7):834–838. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1188379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi S, Verma T, Sanghvi T, Frongillo EA. Path to severe acute malnutrition in children below 2 years of age: Findings of qualitative research in Uttar Pradesh, North India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2019;7(2):246–252. doi: 10.1016/J.CEGH.2018.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, Uauy R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandhiok N, Singh KJ, Sahu D, Singh L, Pandey A. Changes in exclusive breastfeeding practices and its determinants in India, 1992–2006: Analysis of national survey data. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2015;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0059-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. Awareness and health care seeking for newborn danger signs among mothers in peri-urban Wardha. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;76(7):691–693. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul S, Khalil R, Yousafzai MT. Newborn care knowledge and practices among mothers attending pediatric outpatient clinic of a hospital in Karachi Pakistan. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2014;8(2):167–175. doi: 10.12816/0006083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon S, Das JK, Salam RA, Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Breastfeeding promotion interventions and breastfeeding practices: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(SUPPL. 3):S20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). (2017). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. In: International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. Retrieved December 10, 2020. 10.1093/aje/kwm120

- Indian Population Census. (2020). Dakshina Kannada District Population Census 2011–2020, Karnataka literacy sex ratio and density. 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/252-dakshina-kannada.html

- Madhu K, Chowdary S, Masthi R. Breastfeeding practices and newborn care in rural areas: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine : Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. 2009;34(3):243–246. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.55292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S, Zodpey SP, Vidyasagaran AL, Sharma K, Raj SS, Neogi SB, Pathak G, Saraf A. Assessment of essential newborn care services in secondary-level facilities from two districts of India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2014;32(1):130–141. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v32i1.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouf R, Henderson J, Alderdice F. Expectations and experiences of hospital postnatal care in the UK: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. British Medical Journal Open. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder S, Taneja S, Bahl R, Mohan P, Strand TA, Sommerfelt H, Kirkwood BR, Goyal N, Hombergh H, Martines J, Bhandari N. Effect of implementation of integrated management of neonatal and childhood illness programme on treatment seeking practices for morbidities in infants: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g4988. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshram II, Mallikharjun Rao K, Balakrishna N, Harikumar R, Arlappa N, Sreeramakrishna K, Laxmaiah A. Infant and young child feeding practices, sociodemographic factors and their association with nutritional status of children aged <3 years in India: Findings of the national nutrition monitoring bureau survey, 2011–2012. Public Health Nutrition. 2019;22(1):104–114. doi: 10.1017/S136898001800294X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, I., Rose, M., Cordero, D., Fallace, S., & Sanghvi, T. (2004). The components of essential newborn care. Arlington Virginia Partnership for Child Health Care Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival [BASICS] 2004.

- Okawa S, Gyapong M, Leslie H, Shibanuma A, Kikuchi K, Yeji F, Tawiah C, Addei S, Nanishi K, Oduro AR, Owusu-Agyei S. Ghana EMBRACE implementation research project team. Effect of continuum-of-care intervention package on improving contacts and quality of maternal and newborn healthcare in Ghana: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):25347. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025347Opadeyi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opadeyi AO, Fourrier-Réglat A, Isah AO. Educational intervention to improve the knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare professionals regarding pharmacovigilance in South-South Nigeria. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 2019;10:204209861881627. doi: 10.1177/2042098618816279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Badhoniya N, Khadse S, Senarath U, Agho KE, Dibley, M. J. for the South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network (SAIFRN) Infant and young child feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in India: Secondary data analysis of national family health survey 2005–06. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2010;31(2):314–333. doi: 10.1177/156482651003100221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemo K, Phillips D, Hutchinson AM. An Exploration of breastfeeding practices by Bhutanese women. Journal of Human Lactation. 2019;35:181–191. doi: 10.1177/0890334418801289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsegaye M, Ajema D, Shiferaw S, Yirgu R. Level of exclusive breastfeeding practice in remote and pastoralist community, Aysaita woreda, Afar Ethiopia. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2019;14(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13006-019-0200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2015). Committing to child survival: a promised renewed. Progress Report. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/APR_2015_9_Sep_15.pdf

- United nations. (2018 ). THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J., França, G. V., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., et al. (2016). Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet,387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- WHO (2002) Promoting Effective Perinatal Care 2002 essential newborn care and breastfeeding training modules WHO Regional Office for Europe. WHO 1–152.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available on request.

Not applicable.