Abstract

Aim: To assess the intentions of general dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, assistants and technicians graduated from Lithuanian educational institutions in 0032010 to engage in practice in foreign countries. Material and methods: A questionnaire survey was carried out among all graduates (N = 347) general dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, assistants and technicians in Lithuania in 2010. The response rate was 82.7%. Results: 32.4% of graduates from all oral health specialties mentioned their intentions to emigrate from Lithuania. The highest rate of emigration intentions was found among dental assistants (35.5%) and general dentistry graduates (26.9%). Factors related to higher reported intentions to emigrate were relatives or friends residing in other states, self-rating of personal unhappiness, or residing in large cities. As many as every fourth (23.1%) dental hygienist, assistant and technician graduates had already planned, arranged and organised for emigration. Major destination countries are the UK, Ireland, Norway and Sweden. Of all oral health professionals, the highest rate of reported intentions to emigrate was among dental hygienists, assistants and technicians, therefore many of them will not join the professional community in Lithuania. Conclusion: The survey gives indications about the possible magnitude of emigration of oral health professionals from Lithuania and is the first study of its kind. The results show that Lithuania is a major sending country in the context of international oral health professionals’ migration flows.

Key words: Oral health professionals, international migration

INTRODUCTION

Since Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, the oral health care system as well as the entire health care system, have experienced a complex transformation through numerous reforms. Oral health professionals were the first among other health professionals to start working as private practitioners. This growing private sector was able to afford modern high-quality materials and sophisticated equipment, enabling dentists to perform state-of-the-art therapies. All these changes contributed to significant improvement in the quality of dental care for patients1., 2..

Today, the most urgent issue in furthering the oral care system is the planning of human resources, including dentists, dental assistants, hygienists and dental laboratory technicians. Deficiencies in the planning of oral health professionals’ supply and scope leads to an inefficient national education system, as well as to an inefficient use of the funding allocated to oral health care3., 4., 5..

Migration of oral health professionals is a problem that needs to be taken into account in the context of oral health workforce planning. The push and pull factors of different countries and regions have increased international migration flows, as exemplified by a few numbers: 25% of dentists working in the UK are foreign-born, in the USA and France the numbers are reaching 15%6. A Lithuanian survey conducted in 2004 just before Lithuania’s accession to the EU, investigating possible migration intentions indicated that 60.7% of medical residents and 26.0% of physicians intended to leave for the EU or other countries7. Push factors for migration have become more relevant with the current economic recession through increasing unemployment rates, working for shorter hours, or being paid less8. As many as 6.6 per 1,000 Lithuanian inhabitants emigrated (n = 21,970) in 2009, and an even higher number has been projected for 20109. However, so far no surveys investigating the situation regarding Lithuanian dentists or other oral health professionals’ migration intentions have been carried out. International migration of oral health professionals is a key issue for the Lithuanian health care system and the profession at large.

Therefore the aim of the present survey was to assess the intentions of general dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, assistants and technicians to engage in professional practice outside of Lithuania after graduation in 2010.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A questionnaire survey was carried out in May and June 2010, involving final year students prior to their final examinations. The present study involved interviewing all graduates (n = 347); general dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, assistants and technicians in Lithuania. Questionnaires were distributed in all major Lithuanian higher dental educational institutions, namely, Vilnius University, Kaunas University of Medicine, Kaunas, Klaipeda, Siauliai, Panevezys and Utena Colleges. In order to increase the response rate, questionnaires were distributed to student groups during general lectures and students were asked, where possible, to complete the questionnaires immediately. Answers were received from 287 respondents which constituted a response rate of 82.7%. The composition and details of a sample questionnaire are presented in Table 1. Due to the required anonymity, a non-response analysis was not feasible.

Table 1.

Oral health specialist graduates in Lithuanian educational institutions in 2010 (the sample)

| Educational institution | General dentists* | Dental specialists* | Dental hygienists* | Dental technicians* | Dental assistants* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vilnius University | 22/22 (100%) | 8/9 (88.9%) | – | – | – |

| Kaunas University of Medicine | 81/100 (81.0%) | 14/15 (93.3%) | 8/22 (36.4%) | – | – |

| Kaunas college | – | – | 21/26 (80.8%) | 21/25 (84.0%) | 16/19 (84.2%) |

| Klaipeda college | – | – | – | – | 13/15 (86.7%) |

| Šiauliai college | – | – | – | – | 21/22 (95.5%) |

| Panevežys college | – | – | 15/19 (79.0%) | – | 16/18 (88.9%) |

| Utena college | – | – | – | 18/22 (81.8%) | 13/13 (100%) |

| All educational institutions* | 103/122 (84.4%) | 22/24 (91.7%) | 44/67 (65.7%) | 39/47 (83.0%) | 79/87 (90.8%) |

Respondents/all graduates (response rate).

The structured questionnaire was developed based on examples of similar surveys7., 10., 11. and the respondents were requested to provide answers relating to their intentions to emigrate, preferred destinations, the sincerity of their decision, intentions to work within their profession, time intended to spend abroad, in addition to other closed questions. Pull and push factors which might have an impact on the decision to migrate were rated according to a 5-point Likert scale from the score ‘1’ defining the factor as totally unimportant, to ‘5’ as very important. The questionnaire also collected information about personal characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, number of children, place of residence and knowledge of foreign languages. The English translation of the survey form is included in the Appendix.

SPSS (version 13.0; Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for statistical analyses with the threshold for the significance set at P < 0.05. Since the focus of the present inquiry was explore migration intentions, only the respondents who intended to migrate (n = 93) were included in the descriptive analysis. These univariate analyses were used to describe the sample in regards to personal characteristics and simple migration-related questions. Bivariate analyses (Chi-squared test) were employed to relate graduates’ specialty and intentions to migrate, the firmness of the decision, the intentions to work according to profession and time intended to spend abroad. The means and 95% CI for the 5-point Likert scale answers were calculated and the results compared in order to measure the importance of the statements about the pull factors. In order to simplify the results and discussion, the answers of similarly trained and evaluated professionals – dental hygienists, assistants and technicians – were joined together into one group; the answers of all the respondents were also summarised and presented. The impact of graduates’ personal characteristics, demographic and other factors on the decision to migrate were studied by means of a linear multiple logistic regression. The dependent variable was the intention to migrate. The independent variables were gender, marital status, place of residence, knowledge of foreign languages, family or friends who would facilitate the settlement abroad, as well as the self-perception of personal wellbeing and happiness.

RESULTS

Of all graduates surveyed, general dentists represented the largest group (n = 103). Among the respondents were 79 dental assistants, 44 dental hygienists, 39 dental technicians, and 22 dental specialists (Table 1). In terms of gender, the sample consisted of 18.5% males and 81.5% females. The respondents’ average age was 24.3 years (SD = 3.75). The majority of respondents (67.1%) were single (including 0.7% divorced), 32.2% had a partner (21.7% were married and 10.5% lived in legal partnerships) and 15.7% of respondents had children. Among the respondents, 59.4% lived in big Lithuanian cities (Vilnius, Kaunas, Klaipeda, Siauliai, Panevezys – number of inhabitants exceed 100,000), 27.6% in other cities and 12.9% in smaller towns or rural areas.

One third (32.4%) of all respondents reported intentions to migrate. Dental specialists (3.2%) had the lowest intentions to emigrate; while dental assistant graduates scored the highest rate (35.5%) among graduates intending to seek employment abroad. General dentists reported a rate of 26.9%, 19.4% of dental hygienists and 15.1% of technicians were planning to leave the country (P < 0.05).

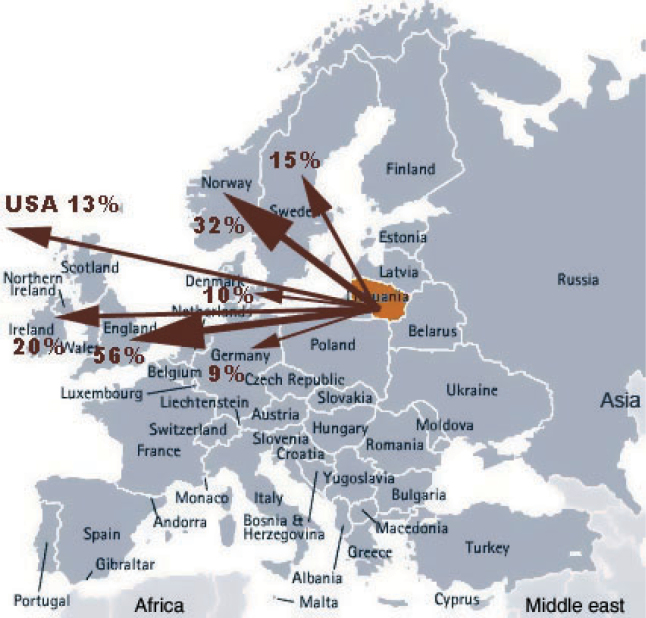

Respondents were asked to provide their three favourite countries for migration. The UK was the most popular country (56%), followed by Norway (32%), Ireland (20%) and Sweden (15%) (Figure 1). The USA (13%), Denmark (10%) and Germany (9%) were also mentioned. In this respect responses were similar among all oral health specialist graduates.

Figure 1.

Migration destinations for oral health specialities graduates in Lithuania.

None of general dentists or dental specialist graduates respondents had taken the final decision to migrate, though 23.1% of dental hygienists, assistants and technicians in total already had everything finally planned and organised (Table 2). The results showed that 15.4% of dental hygienists, assistants and technicians planned to work in other than their trained profession. However none of the dentists intending to migrate had plans to change their occupations. It was also noted that (P > 0.05) dental hygienists, assistants and technicians intended to stay abroad for a shorter time: 16.9% of these graduates planned to spend abroad 1 year and less, while general dentists and dental specialists indicated a longer duration of their intended stay.

Table 2.

Oral health specialist graduates according to the firmness of the decision, the intentions to work in the trained profession and planning the duration of the stay abroad

| Question and answer | All graduates (n,%), (n = 93) | General dentists (n,%), (n = 25) | Dental specialists (n,%), (n = 3) | Dental hygienists, assistants and technicians (n,%), (n = 65) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How firm is your decision? χ2 = 8.61, P = 0.072* | ||||

| Final (definitive) decision | 15/16.1% | – | – | 15/23.1% |

| Advanced project | 23/24.7% | 9/36.0% | 1/33.3% | 13/20.0% |

| Vague project | 55/59.1% | 16/64.0% | 2/66.7% | 37/56.9% |

| Do you plan to work in your profession while being abroad? χ2 = 4.99, P = 0.082* | ||||

| Yes | 81/87.1% | 25/100% | 3/100% | 53/81.5% |

| No | 10/10.8% | – | – | 10/15.4% |

| How long do you plan to work abroad? χ2 = 8.62, P = 0.071* | ||||

| One year and less | 11/11.8% | – | – | 11/16.9% |

| Several years | 52/55.9% | 19/76.0% | 2/66.7% | 31/47.7% |

| For ever | 28/30.1% | 5/20% | 1/33.3% | 22/33.8% |

| What are you prepared to do to be able to leave abroad and work there? χ2 = 7.21, P = 0.125* | ||||

| Learn and improve language | 66/71.0% | 19/76.0% | 2/66.7% | 45/69.2% |

| To occupy lower position than your qualification | 13/14.0% | – | – | 13/20.0% |

| To take up additional professional training courses | 56/60.2% | 18/72.0% | 3/100.0% | 35/53.8% |

Chi squared test between answers and the groups of graduates.

Respondents were also asked what they were prepared to undertake to be able to leave Lithuania and work abroad (Table 2). The majority of graduates were prepared to study or improve their foreign language skills, and a slightly lower number were willing to take additional professional training and development courses. It is interesting to note that none of general dentists and dental specialists were prepared to take up any position inferior to their professional qualification. However, in order to work abroad, 20.0% of dental hygienists, assistants and technicians were prepared to accept a less qualified job.

From all listed pull factors for migration (Table 3), the possibility to earn money for personal housing, higher salary, possibility for new acquaintances, better living and working conditions were identified as the most important by the respondents (mean = 4.4–4.46, according to the means for the 5-point Likert scale) (P > 0.05). These were followed by increased stability, possibility to improve the foreign language skills, possibility to earn money for private business (4.30–4.24). Though lesser in significance but still quite important factors for the respondents were better career chances and the possibilities to grow professionally (4.23).

Table 3.

The pull factors for migration and their importance for oral health specialist graduates

| The pull factor | Mean | 95% CI* |

|---|---|---|

| Possibility to earn money for personal housing | 4.49 | 4.32–4.66 |

| Higher salary | 4.47 | 4.32–4.62 |

| Possibility for new acquaintances | 4.47 | 3.34–5.59 |

| Better living conditions | 4.46 | 4.30–4.61 |

| Better working conditions | 4.47 | 4.31–4.62 |

| Better social guaranties, stability | 4.32 | 4.14–4.49 |

| Possibility to improve language skills | 4.30 | 4.13–4.48 |

| Possibility to earn money for private business | 4.24 | 4.05–4.43 |

| Wider possibilities for career | 4.23 | 4.06–4.40 |

| Possibility to acquire professional skills, good professional experience | 4.23 | 4.05–4.40 |

CI, Confidence Interval.

The results of the multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4) showed that the likelihood of migrating was 3.1 times higher among the graduates who had relatives or friends abroad (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.68–5.85). The probability of leaving Lithuania for graduates who did not feel personally happy was 2.1 times higher as compared to their happy counterparts (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.03–4.44). Living in big cities significantly increased the possibility of migration by 1.9 times (OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.06–3.46). Other factors, such as age, gender, marital status, number of children, knowledge of foreign languages did not have a significant impact on graduates’ intention to migrate.

Table 4.

The impact of graduates’ personal characteristics, demographic and other factors on their decision to migrate

| Independent variables | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.90 (0.81–1.01) | 0.077 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.71 (0.85–3.46) | 0.134 |

| Female | 1.00 | ||

| Marital status | Has a mate | 1.25 (0.61–2.54) | 0.541 |

| Single | 1.00 | ||

| Number of children | None | 1.23 (0.43–3.49) | 0.699 |

| 1 and more | 1.00 | ||

| Knowledge of foreign languages | English | 3.70 (0.78–17.48) | 0.099 |

| Other languages | 1.00 | ||

| Do you have relatives or friends abroad? | Yes | 3.14 (1.68–5.85) | <0.0001* |

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Do you feel happy? | No/partly happy | 2.14 (1.03–4.44) | 0.041* |

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| Place of residence | Big cities | 1.92 (1.06–3.46) | 0.031* |

| Other cities/villages | 1.00 | ||

P, significance level; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

After Lithuania regained the desired independence all emigration was seen as a lack of nationalism and had a rather negative connotation. Today, after 20 years of independence, salaries in Lithuania are still lower than in most European countries. Interestingly, emigration has now gained a positive nuance; it became almost fashionable to leave the country in order to earn more money. This view is particularly prevalent among young people, who often follow friends and relatives already residing abroad.

The present study was the first attempt to examine the intentions of general dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, assistants and technicians, and graduates of Lithuanian educational institutions to practice abroad. The results may be biased since the intentions of the graduates may differ from their real actions and over-reporting may have occurred. Optimistic intentions of young people about migration possibilities might diminish when they face complicated emigration procedures, living conditions and/or administrative issues. The evaluation of migration intentions may have some shortcomings in the methodology; however, the results of the present study clearly indicate the amount and scope of migration intentions that may influence the balance in the supply of and demand for oral health specialist workforce in Lithuania in the future. The expressed intention to leave Lithuania is an important factor to take into account when considering emigration controls for oral health professionals. The study also highlights that Lithuania is a significant source country for the international migration flows of oral health professionals.

The study has shown that the highest rate of migration intentions was found among dental assistants and general dentist graduates (35.5% and 26.9%, respectively). While the absolute number is really high, it is still lower than among medical residents in Lithuania (60.7%), dentists in Estonia (47.5%), physicians in Hungary (46.4%) and Czech Republic (58.5%) before the accession of these countries to the EU7., 9., 10.. The lowest desire to migrate was indicated by dental specialists: only 3.2% showed intentions to migrate. They were 3–4 years older than other respondents (27.5 ± 2.8 vs. 24.0 ± 3.7 respectively), but no differences between groups were found for marital status or number of children in the family (P < 0.05). Earlier studies have shown a strong link between the professional’s age and the intention to migrate7.with migration intentions decreasing with higher age. This may also be due to their higher qualification, professional involvement and esteem, better financial position or professional satisfaction with their career opportunities.

The results showed that the major destinations of oral health professionals from Lithuania are the UK, Ireland, Norway and Sweden. The UK is also one of the major destinations of international migration flows6. Intention to migrate to the Nordic countries is not as highly expressed compared to other countries among these Lithuanian graduates, while the USA was also a less preferred option for study graduates compared to the international flow. This could be related to difficulties with recognition of Lithuanian diplomas in the USA. In 2004 the major directions for the migration of medical residents and physicians were Germany, UK and the Nordic countries7. However, Germany does not seem to be a popular destination among oral health professionals.

Although the firmness of the decision to migrate was generally rather weak among dental graduates and dental specialists, as many as every fourth dental hygienist, assistant and technician had already arranged for the emigration; 57.1% of them intended to leave for an indefinite stay, 28.6% for several years and only 14.3% for 1 year or less. Therefore many of dental hygienist, assistant and technician graduates may not become part of the domestic professional workforce. Of all migrating professionals, 64.3% planned to work according to their professional qualification while 35.7% were prepared to undertake other occupations.

As in other developing countries11., 12., 13., the most important pull factors for oral health professionals’ migration tended to be the financial and finance-related issues (possibility to earn money for private housing, higher salary, better living and working conditions, increased stability). Other pull factors, such as factors related to the shortage of professional skills or better prospects for career were less though still very important for Lithuanian oral health professionals.

According to the multiple logistic regression analysis, the likelihood to emigrate was also higher for big city residents. The centralisation of oral health specialists is clearly expressed in Lithuania14., 15.. Therefore it is difficult to join the professional community in big cities. In rural areas the working and living conditions are worse and the salaries are lower so that only few city residents want to move there. They prefer to join the trend to emigrate as an easier way for a comfortable professional and private life.

Consequences for the Lithuanian oral health workforce

In 2010 there were 9.3 general dentists for every 10,000 Lithuanian inhabitants16. The number is quite high when compared to other countries and the mean for EU17. In this context it may be argued that emigration of general dentists may help reduce an oversupply. However, the demand for dental specialists in the country should be assessed before making conclusions about the appropriate ratio.

For other than dentists there is an absolute shortage of dental assistants with only 0.61 dental assistant per dentist in Lithuania16. This indicates that many dentists work without dental assistants. Some dentists, particularly in remote areas, do so on purpose due to financial reasons, thus reducing the demand for dental assistants and greatly diminishing the quality of dental care. Many dentists still do not realise how efficient practice with dental assistant can be. Lithuanian dental schools still do not teach contemporary four-handed practice and therefore dentists often do not see the need to work with a chairside assistant. Only the inclusion of this subject in the curriculum could improve the situation in the long term. The high emigration rates for dental assistants found in this study indicate a growing discrepancy between the supply and demand of the dental assistants in future.

Given the high costs of dental education which are covered by the government, international migration may be considered as a loss to the national economy, justifying government controls and regulations. However, since the income of dentists is closely related to the performance of the national economy, the possibility of controlling income as a push factor is limited. New legislation for the gradual increase of salaries in the public health care sectors came into effect in 2005. As they were not applicable for the private institutions, it provided only a minimal improvement for many, which, in addition, withered away because of adjustments during the economic recession. No further measures were applied to control emigration from Lithuania. The Lithuanian Dental Chamber, the professional organisation of oral health professionals, advocates tightening the rules requiring oral health specialists whose studies were state-supported to practice in Lithuania for several years after graduation. However, the enforcement of such rules is complex and difficult.

RECOMMENDATIONS

International emigration of oral health professionals is a significant issue for Lithuania, its health care system and the economy. The impact of the phenomenon is not fully understood and this study should be seen as a snapshot of certain aspects related to the problem. We encourage further research on the overall economic impact of emigration, the effect on access and quality of oral care as well as into policy options for better regulation and control. It would be an important first step if all national stakeholders would recognise the problem and consider it as part of the overall goal to provide every Lithuanian citizen with the best possible oral care.

APPENDIX: THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE SURVEY FORM

The questionnaire about the intentions of Lithuanian oral health specialties graduates to practice abroad

This questionnaire is anonymous. The gathered data will be confidential and used only for scientific purpose. Please answer the questions by marking the right number(s), collumns and filling in the lines where needed.

15. How important are these pull factors for migration in your case?

| The pull factor | Totally unimportant | Unimportant | Partly important | Important | Very important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possibility to earn money for personal housing | |||||

| Higher salary | |||||

| Possibility for new acquaintances | |||||

| Better living conditions | |||||

| Better working conditions | |||||

| Better social guaranties, stability | |||||

| Possibility to improve language skills | |||||

| Possibility to earn money for private business | |||||

| Wider possibilities for career | |||||

| Possibility to acquire professional skills, good professional experience |

16. Do you feel happy?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very unhappy | Unhappy | Partly happy | Happy | Very happy |

REFERENCES

- 1.Puriene A, Petrauskiene J, Balciuniene I, et al. [The Assessment of Dentists’ Attitude towards Dental Care System Changes after Independence Regain in Lithuania] Medicinos teorija ir praktika. 2008;14:152–158. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puriene A, Petrauskiene J, Balciuniene I, et al. [Patient satisfaction with dental care in Lithuania] Sveikatos mokslai. 2008;5:1921–1957. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakaite Z. Kaunas Medical University; Kaunas: 2006. Requirement and supply projections for dentists, MSc thesis. http://vddb.library.lt/fedora/get/LT-eLABa-0001:E.02~2006~D_20060608_152310-75633/DS.005.0.01.ETD. Accessed 20 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starkiene L, Padaiga Z, Reamy J, et al. Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe; Kaunas: 2007. [Experience of human recourses planning in health care and pharmacy in Lithuania] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaizauskiene A, Grabauskas V, Kucinskiene Z, et al. Kaunas Medical University; Kaunas: 2003. [Physician Planning in Lithuania in 1990–2015] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benzian H, Beaglehole R, Crail J et al. International migration of dentists. Where from and where to? IADR meeting; 2010 May. Poster No.: 855.

- 7.Stankunas M, Lovkyte L, Padaiga Z. [The survey of Lithuanian physicians and medical residents regarding possible migration to the European Union] Medicina (Kaunas) 2004;40:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balezentis A, Vijeikis J. [Crisis management factors and means in Lithuanian enterprises] Manag theory stud rural bus infrastruct dev. 2010;23:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.International migration [Internet]. Department of Statistics under the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. 2010. Available from: http://db1.stat.gov.lt. Accessed 10 November 2010

- 10.Borzeda A, Bonlarron AG, Gregoire-Borzeda C, et al. Ministry of Social Affairs, Labor and Solidarity; Paris: 2002. European enlargement: do health professional from candidate countries plan to migrate? The case of Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vork A, Kallaste E, Priinits M. Migration Intentions of Health Care Professionals: the Case of Estonia [Internet]. 2004 June 4. Available from: http://www.praxis.ee/fileadmin/tarmo/Projektid/Too-ja_Sotsiaalpoliitika/Tervishoiutootajate_migratsioon_Eestist/11_labour_Migration.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2010

- 12.Buchan J. International recruitment of health professionals. BMJ. 2005;330:210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7485.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2006. Health worker migration in the European region: country case studies and policy implications. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0009/102402/E88366.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dentistry in Lithuania 2006. Lithuanian Dental Chamber; 2006

- 15.Janulyte V, Puriene A, Linkeviciene L, et al. The orthodontic treatment in Lithuania: accessibility survey. Stomatologija. 2008;10:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The register of dentists’ and dental assistants’ licences in Lithuania [Internet]. Lithuanian Dental Chamber; 2010 October 27. Available from: http://www.odontologurumai.lt/index.php/veikla/licencijavimas/licenciju_sarasai/4901. Accessed 1 December 2010

- 17.World Health Organisation, Regional Office for Europe . WHO; Copenhagen: 2010. European health for all database. [Google Scholar]