Abstract

Cells newly transformed with plasmid R1162 DNA were used as donors in conjugal matings to determine if the plasmid replication genes are necessary for transfer. An intact system for vegetative replication is not required for transfer at normal frequency, but the plasmid primase, in the form linked to the nickase, must be present in donor cells.

The basic features of intercellular DNA transport during bacterial conjugation are similar for a wide variety of different plasmids in gram-negative bacteria (35). In the donor cell, one DNA strand is cleaved at a unique site within a locus called the origin of transfer (oriT) and is then unwound and passed in a 5′-to-3′ direction into a recipient cell. The cleaving protein remains covalently linked at the 5′ end of the strand and recircularizes the molecule after a round of transfer. Because only one strand is transferred, synthesis of the complementary strand is required for survival of the plasmid in the recipient. Early studies demonstrated such synthesis for the F factor and also revealed that the transferred strand was replaced by synthesis in the donor (30, 31). However, it should be noted that replacement synthesis in donor cells is not obviously required, particularly for multicopy plasmids where the overall transfer frequency is low, since the occasional loss of a molecule through conjugation would have little impact on plasmid maintenance.

Apart from strand replacement, replication could play another role in conjugation. The DNA strands are unwound ahead of the replication fork, and the machinery of DNA replication could be conscripted to separate strands during conjugation. Such an idea was generally discarded, once it was shown that the F factor and several other large plasmids were transferred at the nonpermissive temperature from donor cells containing a temperature-sensitive dna mutation (9, 13, 16, 31, 34). However, these early genetic experiments suffered from the shortcoming that the ts mutation might be particularly leaky for conjugation, when limited amounts of replication would be required. An additional problem is that the mutation might be suppressed by other, overlapping functions encoded by the chromosome or plasmid. The latter problem is particularly relevant for a large plasmid such as F, which contains multiple replicons and which probably encodes more than one mechanism for initiation of DNA synthesis (17, 20). Moreover, a general requirement for replication cannot be determined by cloning, since the vector replicon could provide a substitute system for replication.

We decided to reinvestigate the possible role of the plasmid replication genes in conjugation, either for strand replacement or for initiation of a round of transfer. We selected the plasmid R1162, which is simpler than plasmid F, as a model system and used conditions where initiation of replication was stringently inhibited.

R1162 encodes three proteins required for its conjugal mobilization: MobA, which cleaves and ligates the transferred strand (6), and two accessory proteins, MobB and MobC. MobC assists in localized separation of the DNA strands at oriT (38); MobB stabilizes the complex of Mob proteins at oriT and also has an additional function in transfer (23). In addition, R1162 encodes three replication proteins (25), a helicase and an iteron-binding protein, the products of the repA and repC genes, respectively, and a primase (see Fig. 2). The primase is encoded in the repB′ region and is translated both as the C-terminal domain of MobA and separately (28). Both forms of the primase are active and sufficient for plasmid replication both in vitro (26) and in vivo (14a). Each DNA strand has an initiation site for the primase within the origin of replication; there are no known secondary sites in R1162 for this primase or for other priming systems (3).

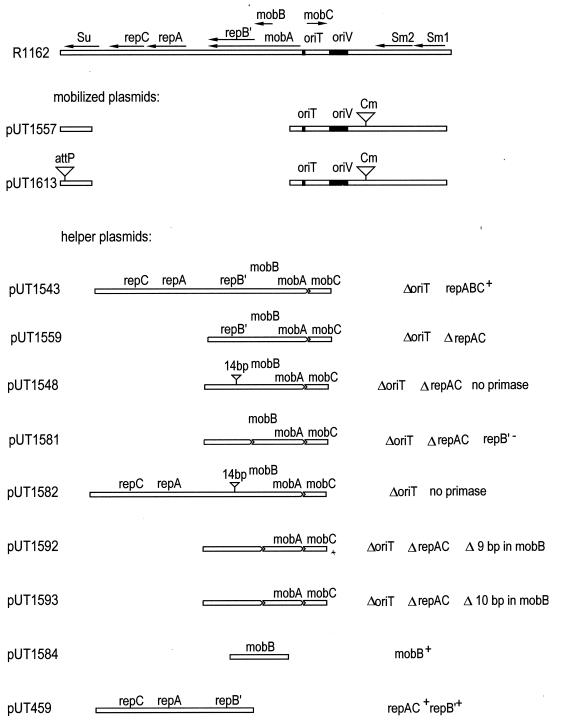

FIG. 2.

Map of R1162 (top) and fragments of R1162 DNA in the different plasmids used in this study. The horizontal bar, interrupted at the site of a deletion, indicates the R1162 DNA present in each plasmid. The filled regions of the bar designate the locations of the origin of replication (oriV) and the origin of transfer (oriT). The locations and direction of transcription of the genes for replication (rep), mobilization (mob), resistance to streptomycin (Sm1 and Sm2), and resistance to sulfonamides (Su) are shown by the arrows on the map of R1162. Those genes retained in the other plasmids are indicated in each case. The inverted triangles indicate the locations of cloned DNA containing either attP, a gene for chloramphenicol resistance (Cm), or a 14-bp oligonucleotide insertion. Construction of these plasmids is outlined in Table 1.

Replication of plasmid DNA in the donor is not required for transfer.

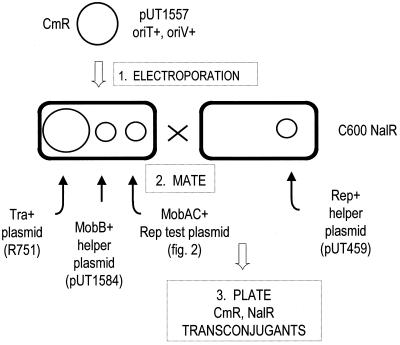

To investigate the role of replication in conjugal transfer of R1162, we carried out the experiment outlined in Fig. 1. We first constructed by electroporation a population of potential donor cells lacking some or all of the R1162 replication proteins. These were then immediately mated, and transconjugants were selected by plating on medium containing antibiotics. The plasmid introduced by electroporation and then transferred was pUT1557, a derivative of R1162 lacking all the replication genes (Fig. 2). This plasmid also contains a 952-bp DNA fragment (3) encoding resistance to chloramphenicol. The Cmr gene was introduced because of the very low background following selection. The additional DNA contains no pas sites and is inactive for initiation of R1162 DNA replication when the normal system of replication is disabled (3).

FIG. 1.

Experimental strategy to examine conjugal transfer in the absence of plasmid vegetative replication.

Plasmid pUT1557 was introduced into cells that contained additional plasmids, which are needed to create potential donors for mating. These cells contained R751, an IncP1 plasmid that conjugally mobilizes R1162 at a high frequency (36), and pUT1584 (Fig. 2), which provided a source of MobB, one of the R1162 mobilization proteins. In addition, the cells contained one of the helper plasmids shown in Fig. 2. These all consist of different fragments of R1162 DNA, containing the remaining R1162 mob genes (mobA and mobC) and different subgroups of the R1162 replication genes, cloned into pBR322. Donor strains were all derivatives of the Escherichia coli K-12 strain MV10 (C600 ΔtrpE5) (15). The recipient strain was the nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of MV12 (C600 ΔtrpE5 recA56) (MV12 Nalr) (5) containing pUT459, which provided the Rep proteins for replication of pUT1557.

For electroporation, approximately 1010 cells, grown to mid-log phase in broth, were collected by centrifugation, washed sequentially with 1.0, 0.5, and 0.25 culture volumes of 10% glycerol, and resuspended in 40 μl of this solution. The cells were then mixed with 0.1 μg of pUT1557 DNA, which had been extracted by the alkaline lysis method (19) from cells also containing pMS40 (21), a helper plasmid supporting replication of pUT1557. To eliminate cotransformation with pMS40 DNA, the preparation was digested with the restriction enzyme SmaI before being added to the cells. The mixture was placed in a 0.1-ml cuvette, and the cells were electroporated with a pulse of 1.8 kV. The cells were then resuspended in 1 ml of 2% Bacto Tryptone–0.5% Bacto Yeast Extract–10 mM NaCl–2.5 mM KCl–10 mM MgCl2–20 mM glucose and mixed with 5 × 108 recipient cells in the same medium. The donors and recipients were concentrated by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.1 ml of this medium, and deposited as a spot on a broth plate. Cells were allowed to mate for 90 min at 37°C and were then resuspended in 1 ml of broth, and dilutions were plated on medium containing chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml each). The number of potential donors was determined by plating, on medium containing chloramphenicol, the mating mixture in which the donor strain contained the Rep+ helper plasmid pUT1543. This number was also used to estimate the frequency of mobilization for the matings involving the other donor strains. Electroporation with pUT1385, the replication-proficient parent of pUT1557, was carried out in parallel to detect any significant differences in the transformability of the donor strains. These strains were all transformed at essentially the same frequency by this DNA (data not shown).

When cells containing pUT1543 (Fig. 2), a helper plasmid providing all the replication proteins of R1162, were transformed with pUT1557 and then mated, many transconjugants were obtained (see Table 2). The mating frequency, the number of transconjugants per donor cell, was 6 × 10−3 (Table 1). This frequency is similar to that observed for mobilization of pUT1557 in standard matings from donor cells also containing R751 and pUT1543. Thus, sufficient time was provided in the period between transformation and plating to allow establishment and processing of plasmid molecules for DNA transfer.

TABLE 2.

Mobilization frequencies from donor strains lacking R1162 replication genes

| Test plasmid | Relevant properties of test plasmid | Transconjugants/100 μl of resuspended mated cellsa | Transconjugants/potential donor (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transferred plasmid pUT1557; recipient strain MV12 NalR(pUT459) | |||

| pUT1543 | Rep+ | 3,300, 12,000, 8,100, 7,300, 7,000 | (6.0 ± 1.4) × 10−3 |

| pUT1543b | Rep+ | 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 | <8.3 × 10−7 |

| pUT1559 | Δ(repAC) | 154, 222, 282, 321, 371 | (2.3 ± 0.7) × 10−4 |

| pUT1548 | Δ(repAC), no primase | 0, 3, 1, 0, 1 | ∼1.2 × 10−6 |

| pUT1581 | Δ(repAC) RepB′− | 212, 264, 298, 129, 137 | (1.7 ± 0.7) × 10−4 |

| pUT1582 | No primase | 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 | <8.3 × 10−7 |

| pUT1592 | Δ(repAC) Δ9bp mobB | 248, 358, 192, 230, 369 | (2.3 ± 0.7) × 10−4 |

| pUT1593 | Δ(repAC) Δ10bp mobB | 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 | <8.3 × 10−7 |

| Transferred plasmid pUT1613; recipient strain MV12 NalR(pUT1612) | |||

| pUT1543 | Rep+ | 2,228, 2,386, 2,045, 2,501, 2,260 | (4.4 ± 4.8) × 10−2 |

| pUT1559 | Δ(repAC) | 73, 54, 53, 61, 60 | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 10−4 |

| pUT1581 | Δ(repAC) RepB′− | 94, 80, 103, 87, 78 | (3.5 ± 0.04) × 10−4 |

| pUT1582 | No primase | 2, 3, 4, 3, 1 | (1.0 ± 0.5) × 10−6 |

Results are for five independent matings.

Donor strain lacking R751.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Source, construction, and or reference |

|---|---|

| Plasmids mobilized during conjugation | |

| pUT1557 | Digestion of pUT1385 DNA (3) with FspI and Bst1107I and ligation |

| pUT1613 | Insertion of a 493-bp HindIII-BamHI λ DNA fragment containing the attP gene (1) into pUT1557 at the HpaI site containing oligonucleotide GGAAGCTTCGCGGATCCCC for cloning |

| Helper plasmids for replication in donor | |

| pUT1543 | HincII-EcoO109 R1162 DNA fragment, containing a 48-bp oriT deletion (22), cloned at the EcoRV site of pBR322 7 |

| pUT1559 | ScaI-EcoO109 R1162 DNA fragment, containing a 48-bp oriT deletion (22), cloned at the EcoRV site of pBR322 7 |

| pUT1582 | Similar to pUT1543, but containing a 14-bp oligonucleotide (CTCGAGGCCTCGAG) inserted at the AflIII site |

| pUT1548 | Similar to pUT1559 but containing the same oligonucleotide insertion as pUT1582 |

| pUT1581 | Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis to create a 12-bp deletion removing the initiation codon and ribosome binding site for RepB′ synthesis and to create the AflIII site; the oligonucleotide TTAACGTGATAATATCTTATCACG was inserted at this site (flush-ended with Klenow fragment) |

| pUT1592 and pUT1593 | Introduction of 9 (pUT1592)- and 10 (pUT1593)-bp mobB deletions (14) by AflII-PflMI fragment exchange |

| pUT1385 | (3) |

| pUT1601 | Inactivation of chloramphenicol resistance gene of pACYC184 (10) by filling-in at the EcoRI site. |

| pUT1584 | Replacement of small HindIII-SalI fragment of pWSK129 31 with HindIII-SalI fragment, containing R1162 DNA, from pUT221 (8) |

| pUT459 | (8) |

| pUT1612 | Replacement of small HindIII-SalI fragment of pBR322 with HindIII-SalI fragment from pTAC3422 (1), containing a 1,386-bp λ DNA fragment carrying the int gene. |

Significant numbers of transconjugants were also obtained in a second mating, after electroporation of cells containing the helper plasmid pUT1559 (Table 2). This plasmid is similar to pUT1543 but lacks repA and repC (Fig. 2), so that pUT1557 DNA was not replicated in the potential donor cells. Using the number of pUT1543 potential donors as an estimate of the number also available after transformation with pUT1559, we calculated a mating frequency of approximately 2.3 × 10−4 (Table 2). This value probably underestimates the actual transfer frequency, since the number of pUT1543 donors was determined after the 90-min mating period, which is sufficient time for their number to increase due to growth on the medium. However, the number of potential donor cells containing pUT1559 cannot increase during this period.

The appearance of transconjugant colonies in matings involving pUT1559 indicated that the complete system of vegetative replication of R1162 was not required for conjugal transfer. However, we did additional tests to verify that these colonies did in fact arise from bacterial mating. When R751 was absent from the cells transformed with pUT1543, no colonies of cells resistant to chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid appeared after mating (Table 2). Thus, these colonies were not due to chromosomal mutation or to transformation of recipient cells by the pUT1557 DNA remaining in the medium after transformation. The possibility that transfer of R751 potentiates a recipient cell for transformation by pUT1557 was also ruled out, since no colonies were obtained in other matings, described below, in which R751 was present.

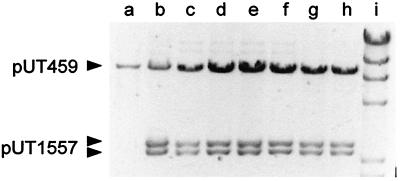

The plasmid DNA content of transconjugant cells from five separate matings involving donor cells containing pUT1559 was analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). In each case, the sizes of the restriction fragments were the same (Fig. 3, lanes d to h) and identical to those obtained after matings involving the Rep+ helper plasmid pUT1543 (lane c) or after transformation of the recipient strain with pUT1557 (lane b). These results indicated that only unaltered pUT1557 and pUT459 were present (the transferring vector R751 was also in most of the transconjugants, but the bands were very faint because of its low copy number). Thus, the transconjugant cells did not arise by recombination between pUT1557 and the helper plasmid and then transfer of the joint molecule. In addition, because all the helper plasmids lack oriT, transient chimeric molecules, due to site-specific recombination at this locus (33), could not have occurred.

FIG. 3.

Plasmid DNA in MV12 Nalr(pUT459) (lane a) and in derivatives containing pUT1557, constructed by transformation (lane b) or by conjugal mating with the donor strain containing helper plasmid pUT1543 (lane c) or helper plasmid pUT1559 (lanes d to h). Each transconjugant for the plasmid DNA in lanes d to h was the result of an independent mating. The DNA was digested with EcoRI before being applied to an 0.8% agarose gel. In lanes c to h, faint, slowly migrating bands were observed. These are derived from the mobilizing vector R751. Lane i contains HindIII-digested λ DNA as marker.

Our results indicate that mobilization of R1162 can occur at a normal frequency in the absence of RepA and RepC, and thus vegetative replication of R1162 is not required. However, these proteins, encoded by pUT459, were present in the recipient cells in our experiments, in order to maintain pUT1557 after transfer. It was possible that RepA and RepC leaked through the conjugal pore and into the donor cell of a mating pair. Although such leakage would not be expected to allow general replication of plasmid DNA in the donor, a transferring plasmid copy, positioned at the conjugal pore, might have access to these proteins. To rule out this possibility, we modified the mating experiment by cloning a 493-bp λ DNA fragment containing the attP gene into pUT1557, to create pUT1613. We also replaced pUT459 in the recipient strain with pUT1612, a pBR322 derivative encoding the λ integrase protein. In a preliminary experiment, we found that after transformation with SmaI-digested pUT1613 and pMS40 DNA, chloramphenicol-resistant transformants that did not contain helper or other replicating plasmids were formed (data not shown). Thus, the replication-defective plasmid could integrate into the chromosome upon entry into the cell (1). Donor cells were electroporated with pUT1613 and mated with MV12 Nalr(pUT1612). Again, transconjugants were obtained not only from donor cells containing the complete set of R1162 replication proteins but also from those lacking RepA and RepC (Table 2). For each donor, the transfer frequencies were similar, whether the mobilized plasmids were rescued by Int-mediated recombination or by providing replication proteins in the recipient.

Although we can only estimate the number of potential donors that are formed after electroporation of Rep− strains, it is clear that the efficiency of transfer is similar, whether or not all the Rep proteins are present in the donor cells. It is possible that each competent cell takes up many molecules of DNA, so that the plasmid copy number in Rep− donors is transiently similar to that in donors in which the plasmid can replicate (at least 10 copies per cell [2]). We transformed the Rep+ donor strain (containing helper plasmid pUT1543) with a mixture of two plasmid DNAs, pUT1557 DNA and an equimolar amount of DNA from pUT1601, a pACYC184 derivative encoding resistance to tetracycline but not chloramphenicol and compatible with all the plasmids in the donor. Cells were plated on medium containing chloramphenicol or tetracycline, and colonies were then tested for resistance to the other antibiotic. In two separate experiments, on average only 14% of the cells receiving one plasmid also received the other. This indicated that during electroporation, competent cells do not generally receive a number of plasmid molecules similar to the copy number of R1162. We conclude that after transformation, plasmid DNA is efficiently targeted to the conjugal apparatus, and this accounts for the high frequency of transfer after electroporation.

MobA-linked primase in the donor is essential for recovery of plasmid DNA in recipient cells.

We have shown elsewhere that the MobA-linked form of the primase increases the efficiency of the mobilization system encoded by R1162 (14). This stimulation requires the cognate primase recognition site, properly oriented for synthesis of the complement to the transferred strand, suggesting that R1162 can use this priming system for DNA synthesis during conjugal transfer. We used electroporation and mating to examine the role of the R1162 primase in transfer. We constructed two additional helper plasmids, pUT1582 and pUT1548, similar to pUT1543 (Rep+) and pUT1559 (ΔrepAC), respectively, but containing an inactivating, 14-bp insertion in the primase-coding region of the plasmid (14). After transformation of these cells with pUT1557 and subsequent mating, very few colonies were obtained in each case (Table 2), indicating that the R1162 primase is involved in transfer.

The results with several other helper plasmids indicate that, as suggested by earlier results (14), it is the linked primase that is principally active. The plasmid pUT1593 is identical to pUT1559 but contains a frameshifting 10-bp deletion in mobB, upstream from repB′. Because of the frameshift, only the short form of the primase is made. The mutation does not affect the N-terminal third of MobA, the region required for transfer (14). However, pUT1593 no longer supported detectable mobilization of pUT1557 (Table 2). In contrast, a nonshifting, 9-bp deletion in the same location still permitted transfer of pUT1557 (pUT1592) (Table 2). Finally, plasmid pUT1581 is similar to pUT1559 but contains an in-frame deletion removing the ribosome binding site and initiation codon of the short form of the primase, so that this form is no longer made (14a). Like pUT1559, pUT1581 allowed mobilization of pUT1557 (Table 2). Thus, of the two forms of primase, the long form is sufficient to ensure mobilization at a high frequency.

The MobA-linked primase is also important for transfer when the incoming plasmid is inserted into the chromosome by the λ integrase. Transconjugants of MV12 Nalr(pUT1612) were formed efficiently when the donor strain contained the helper plasmid pUT1581, which encodes the primase long form. Only a few apparent transconjugants were found when the donor strain contained pUT1582, which does not encode an active primase (Table 2). Presumably, integration of the plasmid by site-specific recombination required restoration of the incoming plasmid DNA to the duplex form.

In several matings, a small number of transconjugant colonies were obtained when primase was absent from the donor cells (Table 2). Colonies were also obtained at a similar frequency when recipient cells lacked either of the rescue plasmids, pUT459 or pUT1612. The cells in these colonies contained pMS40. This background level of transconjugants is presumably the result of matings involving rare donor cells that received both pUT1557 and intact pMS40 during electroporation.

Our results indicate that mobilization of R1162 does not require an intact system of vegetative replication. However, because only a single strand of DNA is transferred, a priming system for its complement is required. In the case of R1162, the plasmid primase, linked to one of the Mob proteins, is used. Utilizing for transfer the plasmid-encoded primase and its cognate recognition site is an obvious adaptation for broad-host-range plasmids. By contrast, narrow-host-range plasmids, such as F and ColE1, probably use cellular mechanisms of priming (37).

Recipient cells containing pUT459 encode primase in amounts sufficient to support replication of transferred molecules. Nevertheless, primase in the recipient could not substitute for an absence of MobA-linked primase in donor cells. Increasing the distance between oriT and oriV reduces the frequency of transfer (14). Thus, we believe that the MobA-linked form of the primase, attached to the 5′ end of the transferring molecule, is also uniquely positioned to prime the complementary strand efficiently. Possibly, priming is initiated at the conjugal pore, with MobA, immobilized at this site, scanning the DNA for the cognate priming site during movement of the DNA strand into the recipient. It is also possible that priming might be required for proper termination. MobA not only ligates single-stranded oriT DNA but also readily cleaves this DNA (6, 27). Synthesis of the complementary strand through oriT, initiated at the neighboring oriV by the primase domain of MobA, would result in a substrate that is poorly cleaved by MobA. This would ensure that the transferred molecule would remain circular.

Several observations suggest that fusion of the primase to the nicking protein evolved after an ancestral plasmid acquired the mobilization genes. The plasmid pTF-FC2 is an IncQ-like replicon and encodes a primase related to RepB′ (11, 12). However, there is no fused form of the primase, and the mobilization genes of the plasmid are unrelated to those of R1162 (24). Another IncQ plasmid, pIE1107 (29), has an arrangement of mob and rep genes similar to that in R1162, and from inspection of the sequence, both a short and fused form of the primase would appear to be synthesized. However, the amino acid sequence at the fusion is different, suggesting that this fusion evolved independently from the one in R1162. Finally, pSC101 encodes a MobA protein similar to that encoded by R1162, but it is not fused to an R1162-like primase (4). It is therefore likely that the fusion followed acquisition of the mob genes and was selected because it improved the frequency of transfer. It is noteworthy that once a priming system is captured, a mob system can become completely independent of its plasmid host, allowing new modes of maintenance. This might have happened in the case of mobilizable transposons, at least some of which might specify their own priming system for transfer (18).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM37462).

We thank Tove Atlung for providing a plasmid as a source of the λ int gene.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung T, Nielsen A, Rasmussen L, Holm F. A versatile method for integration of genes and gene fusions into the lambda attachment site of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;107:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90291-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth P T, Grinter N J. Comparison of the deoxyribonucleic acid molecular weights and homologies of plasmids conferring linked resistance to streptomycin and sulfonamides. J Bacteriol. 1974;120:618–630. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.2.618-630.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker E C, Zhou H, Meyer R J. Replication of a plasmid lacking the normal site for initiation of one strand. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4870–4876. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4870-4876.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernardi A, Bernardi F. Complete sequence of pSC101. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:9415–9426. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.24.9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharjee M, Rao X M, Meyer R J. Role of the origin of transfer in termination of strand transfer during bacterial conjugation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6659–6665. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6659-6665.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharjee M K, Meyer R J. A segment of a plasmid gene required for conjugal transfer encodes a site-specific, single-strand DNA endonuclease and ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Greene P J, Betlach M C, Heyneker H L, Boyer H W, Crosa J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles. II. A multiple cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasch M A, Meyer R J. Genetic organization of plasmid R1162 DNA involved in conjugative mobilization. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:703–710. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.2.703-710.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bressler S, Lanzov V, Lukjaniec-Blinkova A. On the mechanism of conjugation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1968;102:269–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00433718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorrington R, Bardien S, Rawlings D. The broad-host-range plasmid pTF-FC2 requires a primase-like protein for autonomous replication in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;108:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90481-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorrington R, Rawlings D. Characterization of the minimum replicon of the broad-host-range plasmid pTF-FC2 and similarity between pTF-FC2 and the IncQ plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5697–5705. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5697-5705.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenwick R J, Jr, Curtiss R I., III Conjugal deoxyribonucleic acid replication by Escherichia coli K-12: stimulation in dnaB(ts) donors by minicells. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:1212–1223. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.3.1212-1223.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson D, Meyer R. The primase of broad-host-range plasmid R1162 is active in conjugal transfer. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6888–6894. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6888-6894.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Henderson, D., and R. Meyer. Unpublished data.

- 15.Hershfield V, Boyer H W, Yanofsky C, Lovett M A, Helinski D R. Plasmid ColE1 as a molecular vehicle for cloning and amplification of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3455–3459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingsman A, Willetts N. The requirements for conjugal DNA synthesis in the donor strand during Flac transfer. J Mol Biol. 1978;122:287–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kline B. A review of mini-F plasmid maintenance. Plasmid. 1985;14:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Shoemaker N, Wang G-R, Cole S, Hashimoto M, Wang J, Salyers A. The mobilization region of two integrated Bacteroides elements, NBU1 and NBU2, have only a single mobilization protein and may be on a cassette. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3940–3945. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3940-3945.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marko M A, Chipperfield R, Birnboim H C. A procedure for the large-scale isolation of highly purified plasmid DNA using alkaline extraction and binding to glass powder. Anal Biochem. 1982;121:382–387. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masai H, Arai K. Frpo: a novel single-stranded DNA promoter for transcription and for RNA primer synthesis of DNA replication. Cell. 1997;89:897–907. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer R, Hinds M, Brasch M. Properties of R1162, a broad-host-range, high-copy-number plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:552–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.552-562.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perwez T, Meyer R. MobB protein stimulates nicking at the R1162 origin of transfer by increasing the proportion of complexed plasmid DNA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5762–5767. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5762-5767.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perwez T, Meyer R. Stabilization of the relaxosome and stimulation of transfer are genetically distinct functions of the R1162 protein MobB. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2124–2131. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2124-2131.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohrer J, Rawlings D. Sequence analysis and characterization of the mobilization region of a broad-host-range plasmid, pTF-FC2, isolated from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6230–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6230-6237.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scherzinger E, Bagdasarian M M, Scholz P, Lurz R, Ruckert B, Bagdasarian M. Replication of the broad host range plasmid RSF1010: requirement for three plasmid-encoded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:654–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scherzinger E, Haring V, Haring R, Otto S. Plasmid RSF1010 DNA replication in vitro promoted by purified RSF1010 RepA, RepB and RepC proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Otto S, Dobrinski B. In vitro cleavage of double- and single-stranded DNA by plasmid RSF1010-encoded mobilization proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:41–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scholz P, Haring V, Wittmann-Liebold B, Ashman K, Bagdasarian M, Scherzinger E. Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010. Gene. 1989;75:271–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tietze E. Nucleotide sequence and genetic characterization of the novel IncQ-like plasmid pIE1107. Plasmid. 1998;39:165–181. doi: 10.1006/plas.1998.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vapnek D, Rupp W D. Asymmetric segregation of the complementary sex-factor DNA strands during conjugation in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1970;53:287–303. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vapnek D, Rupp W D. Identification of individual sex-factor DNA strands and their replication during conjugation in thermosensitive DNA mutants of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1971;60:413–424. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren G J, Clark A J. Sequence-specific recombination of plasmid ColE1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6724–6728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkins B, Hollom S. Conjugational synthesis of Flac+ and ColI DNA in the presence of rifampicin and in Escherichia coli K12 mutants defective in DNA synthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;134:143–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00268416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkins B, Lanka E. DNA processing and replication during plasmid transfer between gram-negative bacteria. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willetts N, Crowther C. Mobilization of the nonconjugative IncQ plasmid RSF1010. Genet Res. 1981;37:311–316. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300020310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willetts N, Wilkins B. Processing of plasmid DNA during bacterial conjugation. Microbiol Rev. 1984;48:24–41. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.1.24-41.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S, Meyer R. The relaxosome protein MobC promotes conjugal plasmid mobilization by extending DNA strand separation to the nick site at the origin of transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:509–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4861849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]