Abstract

Objective: To determine the prevalence of orofacial injuries among basketball players in Benin City, Nigeria and to survey the athletes’ awareness, attitude and use of mouthguards. Methods: A cross-sectional survey of basketball players in the standard basketball arena in Benin City was conducted between November 2009 and January 2010. A self-administered questionnaire elicited information on demography, the prevalence of oral and facial injuries, distribution of site and cause of orofacial injuries, athletes’ knowledge, attitudes and usage of mouthguards. Data were subjected to descriptive statistics and Chi square test. Results: The response rate was 78%. Of the 156 respondents, 79.5% were male and 20.5% female, with a mean age of 23.1 years. The distributions was amateurs (61.5%) professionals (38.5%). The mean number of injuries in previous 12 months was 3.7 ± 1.8. The prevalence of both facial and oral injuries among the respondents was 62.8% with the lip and gingiva most commonly involved respectively. The common causes of the orofacial injury reported were from elbows of opponents, falling and collisions with other players. The prevalence of injury was not significantly associated with demography, category, competition and duration of participation. More than half had heard and seen mouthguards and the coach was the leading source of information. The reasons for non-use of mouthguard were mostly ignorance, non-availability and non-affordability. Conclusion: The high prevalence of orofacial injury among basketball players reported in this study justifies the need for multidisciplinary injury prevention interventional approach with emphasis on the rules of the games.

Key words: Orofacial injuries, basketball players, mouthguard, trauma, Nigeria

Worldwide, individuals are increasingly participating in an expanding arena of vigorous physical activities as well as competitive sports at all levels. The benefits of such activities are unfortunately associated with injury risks which include orofacial soft and hard tissue trauma1. The aesthetic value of the face makes the effect and impact of orofacial injuries unquantifiable. Contact sports have maintained a relevant place in causation of orofacial trauma2., 3. because the face is the most vulnerable and least protected area of the body. Orofacial sports-related injuries are known to occur across a wide range of both organised and unorganised sports4. These injuries appear to be more numerous in team sports and more severe in individual sports5. A Nigerian study revealed that 57.9% of orofacial injury occurred in sportsmen and women with contact sports accounting for 78.5% and non-contact events resulting in the remaining 21.5%6. Among contact and team sports, basketball obviously carries the highest risk of orofacial injury7., 8., 9. and is the most frequent cause of sports-related emergency department visits for youths and adolescents10.

The prevalence of orofacial injuries in basketball is 34%11. The increasing incidence of orofacial injuries in high impact sports like basketball needs considerable attention8. Gender-based differences in sports-related facial injuries with male: female ratio of 2.4:1 has been documented12. Although some orofacial injuries in sports are unavoidable, the majority are preventable with proper utilisation of mouthguards13. The Academy of General Dentistry recommends that players participating in basketball whether for an athletic competition or leisure activity, should wear a mouthguard while competing14. Anecdotal evidence shows that basketball is becoming a popular sport in Nigeria with orofacial injuries being common as mouthguard wear in basketball appears to be low. There are few studies assessing the prevalence of orofacial injuries among sportsmen and women in Nigeria15., 16., 17. but to date the authors are not aware of any such specific study on orofacial injury on basketball players.

The objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of oral and facial injuries among basketball players in Benin City, Nigeria and to survey the athletes’ awareness, attitude and use of mouthguards.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining ethical approval for the study from University of Benin Teaching Hospital Ethics Committee, a cross-sectional survey of basketball players at four standard basketball pitches; Ogbe Stadium, University of Benin sports complex, S&T Barracks and Emotan secondary school basketball courts in Benin City, Edo State was conducted. The survey was conducted between November 2009 and January 2010. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to elicit information on demography, basketball players, prevalence of orofacial injuries and the type of injury, athletes’ awareness, attitudes and usage of mouthguards. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the survey. Data analysis was done using SPSS version 15.0. (SPSS version 15.0: SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

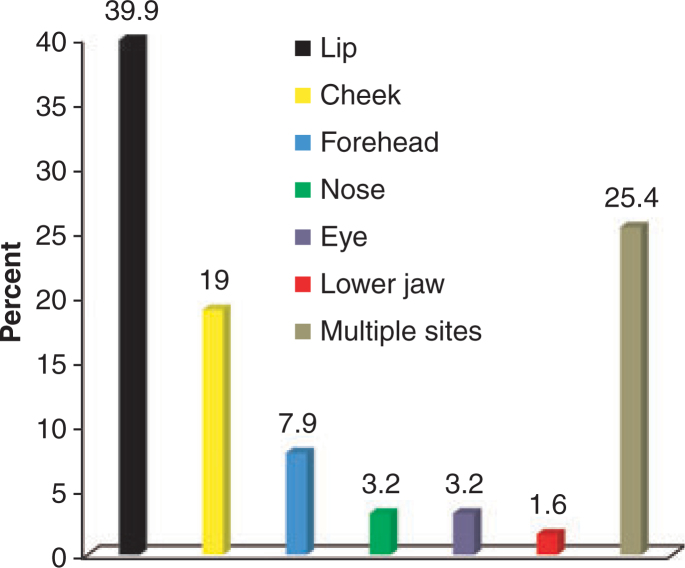

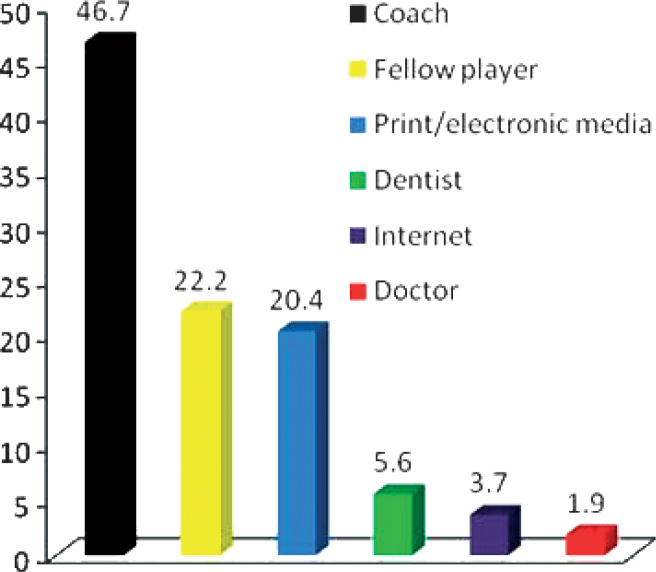

The response rate was 78%. Of the 156 respondents, 79.5% were male and 20.5% female, with a mean age of 23.1 years (SD = 4.8 years). Most were amateurs (61.5%) with the remainder being professionals (38.5%) (Table 1). The mean number of injuries among the respondents in previous 12 months was 3.7 ± 1.8. The prevalence of both facial and oral injuries among the respondents was 62.8% (Table 2), with the lip and gingiva being the most commonly injured facial and intraoral sites respectively (Figure 1). The commonest causes of the orofacial injuries reported were from the elbow of an opponent, a fall and a collision with another player (Table 3). The prevalence of injury was not significantly associated with demography, category, competition and duration of participation. More than half had heard and seen mouthguards and the coach was the leading source of information (Figure 2). The reasons for non-use of mouthguards were mostly ignorance, non-availability and non-affordability.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 40 | 25.6 |

| 20–24 | 58 | 37.2 |

| 25–29 | 46 | 29.5 |

| >29 | 12 | 7.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 124 | 79.5 |

| Female | 32 | 20.5 |

| Position | ||

| Forward | 48 | 30.8 |

| Centre | 24 | 15.4 |

| Point guard | 34 | 21.8 |

| Power forward | 24 | 15.4 |

| Guard | 26 | 16.7 |

| Grade | ||

| Non professional | 96 | 61.5 |

| Professional | 60 | 38.5 |

| Total | 156 | 100.0 |

Table 2.

Prevalence of mouth and facial injury

| Site | Frequency (n) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth alone | 10 | 6.4 |

| Face alone | 18 | 11.5 |

| Both face and mouth | 98 | 62.8 |

| No injury | 30 | 19.2 |

| Total | 156 | 100.0 |

Figure 1.

Site of facial injury experienced by the respondents.

Table 3.

The mechanism of injury experienced by respondents

| Mechanism | Sex | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Fall | 28 (26.4) | 10 (41.7) | 38 (29.2) |

| Elbow | 36 (34.0) | 12 (50.0) | 48 (36.9) |

| Ball | 4 (3.8) | 2 (8.3) | 6 (4.6) |

| Collision with another player | 18 (17.3) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (13.8) |

| Collision with equipment | 10 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (7.7) |

| Multiple mechanisms | 10 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (7.7) |

| Total | 106 (100.0) | 24 (100.0) | 130 (100.0) |

Figure 2.

Sources of information regarding mouthguard among respondents.

DISCUSSION

Basketball is among the sports associated with a high incidence of orofacial injuries in both males and females especially during competition18. In this study, the mean frequency of the injury among the respondents in the previous 12 months was 3.7 ± 1.8. The prevalence of oral and facial injury was high, substantiating the fact that head and neck injuries are very prevalent in basketball7. However, lower prevalences of orofacial injury and trauma have been documented such as 16.6% among Swiss basketball player19, 23% among basketball players in Victoria, Australia20, 31% in Florida high school basketball players21 and 55.4% in Minnesota high schools8. This could be due to the unorganised nature of the game with respondents not playing strictly to the rules of the game thereby making the style of the game more physical22. This also justifies why the common causes of the injuries in this study were from the elbow of an opponent, a fall and a collision with another player. None and sparse use of mouthguards may be contributory18., 23..

In this study injury rates were higher in professional compared to non professionals as reported in previous studies24., 25.., although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.261). The majority of injuries are minor as only a few have been hospitalised due to injury sustained while playing basketball. This tallied with the assertion that most facial injuries sustained while playing basketball are relatively minor, with a few being severe and permanent injuries22.

The facial injuries were mostly in the form of skin abrasions. Lacerations of soft tissues, fracture of the lower jaw and cheek bone and dislocation of the temporomandibular joint were also reported in this study. These patterns of injuries differed from what was earlier documented in a sports festival where the majority of the injuries were lacerations with fracture of the facial skeleton25.

In this study, oral injury was commonly to the tongue and gingiva, while lip injury was the commonest extraoral injury. This is similar to the finding from the Central American and Caribbean Sports Games of the Puerto Rican Delegation over a 20 year period which revealed the lip contusion as the most frequent injury associated with basketball9. In this study, fractured teeth and avulsion were uncommon, which is in agreement with finding of other studies16. The playing position commonly affected by the injuries was the power forward followed by the power guard but this differed in the present study from the findings of previous studies25. The constant contact that the power guard and power forward have with opponents due to their strategic role in defence and attack respectively explains their higher experience of injuries. It is widely reported that orofacial injuries occur more during competition than during training. In this study, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of injuries reported during competition and training. The lesser laurel winning competition in basketball may have been the reason for the similarity in the orofacial injury prevalence.

More than half of the respondents had heard and seen mouthguards, which is comparable to the level of awareness reported among basketball players in China24. Although the coach was the main source of information, the media and fellow players also shared a substantive role in this regard which is consistent with the finding of a previous study24. This reflects an insufficient role of dentists in sports medicine and education25. Mouthguards significantly lower the rates of dental injuries26. Implementation of mandatory mouthguard usage in sports, such as basketball, would decrease such a large number of sports injuries25. Three-quarters believed that a mouthguard can prevent oral injury during basketball but less than a quarter claimed to have used one. The reasons for non use ranged from ignorance about mouthguards, non-availability, non-affordability and possibility of it being a source of discomfort. The high level of ignorance about mouthguards reported in this study was similar to the finding among Japanese high school soccer and rugby players27. The respondents also opined that making mouthguard wearing compulsory during a basketball game and providing a mouthguard free of charge would increase and improve mouthguard wear.

CONCLUSION

This survey revealed a high prevalence of orofacial injury and a low awareness about mouthguard use. This justifies the need for injury prevention and an interventional approach which includes emphasis on the rules of the game, safe landing pattern when falling and the possibility of increased mouthguard wearing by eliminating the identified barriers. Dental professionals’ involvement in educating the public about the importance of using mouthguard protection in contact sports is also advocated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ranalli DN, Demas PN. Orofacial injuries from sport: preventive measures for sports medicine. Sports Med. 2002;2:409–418. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bemelmanns P, Pfeiffer P. Incidence of dental, mouth, and jaw injuries and the efficacy of mouthguards in top ranking athletes. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2000;14:139–143. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulunoglu I, Ozbek M. Oral trauma, mouthguard awareness, and use in two contact sports in Turkey. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22:242–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tesini DA, Soporowski NJ. Epidemiology of orofacial sports-related injuries. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Youth Sports Foundation . National Youth Sports Foundation; Needham, MA: 1994. Fact sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onyeaso CO, Adegbesan OA. Knowledge and attitudes of coaches of secondary school athletes in Ibadan, Nigeria regarding oro-facial injuries and mouthguard use by the athletes. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19:204–208. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2003.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKay GD, Payne WR, Goldie PA, et al. A comparison of the injuries sustained by female basketball and netball players. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1996;28:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvittem B, Hardie NA, Roettger M, et al. Incidence of orofacial injuries in high school sports. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58:288–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amy E. Oro-facial injuries in Central American and Caribbean sports games: a 20-year experience. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmer PA. Basketball injuries. Med Sport Sci. 2005;49:31–61. doi: 10.1159/000085341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanders RA, Bhat M. The incidence of orofacial injuries in sports: a pilot study in Illinois. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:491–496. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linn EW, Vrijhoef MM, de Wijn JR, et al. Facial injuries sustained during sports and games. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newsome PR, Tran DC, Cooke MS. The role of the mouthguard in the prevention of sports-related dental injuries: a review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:396–404. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7439.2001.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Academy of General Dentistry. What is a mouthguard? Available from: URL: http://www.agd.org/public/oralhealth/Default.asp?IssID=331&Topic=S&ArtID=1328#body

- 15.Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Sports related maxillofacial fractures in 77 Nigerian patients. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29:215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saheeb BDO, Sede MA. Orofacial sports – related injuries in a sports festival in Nigeria. Nigerian J Clin Pract. 2003;6:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onyeaso CO. Oro-facial trauma in amateur secondary school footballers in Ibadan, Nigerian: a study of mouthguards. Odontostomatol Trop. 2004;27:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee-Knight CT, Harrison EL, Price CJ. Dental injuries at the 1989 Canada games: an epidemiological study. J Can Dent Assoc. 1992;58:810–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perunski S, Lang B, Pohl Y, et al. Level of information concerning dental injuries and their prevention in Swiss basketball – a survey among players and coaches. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornwell H, Messer LB, Speed H. Use of mouthguards by basketball players in Victoria, Australia. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19:193–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2003.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maestrello-deMoya MG, Primosch RE. Orofacial trauma and mouth-protector wear among high school varsity basketball players. ASDC J Dent Child. 1989;56:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyette RF. Facial injuries in basketball players. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:247–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrow RM, Bonci T. A survey of oral injuries in female college and university athletes. Ath Train. 1989;24:236–237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma W. Basketball players’ experience of dental injury and awareness about mouthguard in China. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:430–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesić N, Seifert D, Jerolimov V. Sports injuries of temporomandibular joints and oral muscles in basketball players. Acta Med Croatica. 2007;61(Suppl 1):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labella CR, Smith BW, Sigurdsson A. Effect of mouthguards on dental injuries and concussions in college basketball. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:41–44. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada T, Sawaki Y, Tomida S, et al. Oral injury and mouthguard usage by athletes in Japan. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1998;14:84–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1998.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]