Abstract

Global Oral Health suffers from a lack of political attention, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. This paper analyses the reasons for this political neglect through the lens of four areas of political power: the power of the ideas, the power of the issue, the power of the actors, and the power of the political context (using a modified Political Power Framework by Shiffman and Smith. Lancet370 [2007] 1370). The analysis reveals that political priority for global oral health is low, resulting from a set of complex issues deeply rooted in the current global oral health sector, its stakeholders and their remit, the lack of coherence and coalescence; as well as the lack of agreement on the problem, its portrayal and possible solutions. The shortcomings and weaknesses demonstrated in the analysis range from rather basic matters, such as defining the issue in an agreed way, to complex and multi-levelled issues concerning appropriate data collection and agreement on adequate solutions. The political priority of Global Oral Health can only be improved by addressing the underlying reasons that resulted in the wide disconnection between the international health discourse and the small sector of Global Oral Health. We hope that this analysis may serve as a starting point for a long overdue, broad and candid international analysis of political, social, cultural, communication, financial and other factors related to better prioritisation of oral health. Without such an analysis and the resulting concerted action the inequities in Global Oral Health will grow and increasingly impact on health systems, development and, most importantly, human lives.

Key words: Global oral health, health systems, oral health planning, political power framework, prioritisation

THE DYNAMICS OF GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH AND POLITICAL PRIORITIES

Public health priorities and political priorities are not necessarily aligned. There are numerous examples of a disproportionate attention and allocation of resources to specific diseases despite a rather limited impact on morbidity and mortality (e.g. polio eradication)1. On the other hand, major causes of childhood mortality such as diarrhoea and infectious diseases are not able to attract adequate political and donor attention1., 2., 3.. Knowledge about the processes and underlying reasons for such mismatches is limited and virtually unknown for oral diseases and their political priority status.

While all major international stakeholders in oral health deplore the neglected state of oral health worldwide4 they have had limited success, so far, in generating major international interest and action in addressing oral health problems. The broader international health community in general is unaware of this critical situation, and the striking disparities both between and within countries in global oral disease burden and access to care5., 6.. Even among the dental profession only a few seem to note the incredible neglect of oral diseases, and even fewer are determined to take bold and tangible action to address this neglect.

This paper examines the neglect of global oral health through the Political Power Framework (PPF) proposed by Shiffman and Smith7, an analytical framework to assess essential factors determining political priorities. The analysis is a first step towards more effective and impactful global oral health advocacy.

GLOBAL ORAL HEALTH – SYMPTOMS OF NEGLECT

The range and size of actors and activities in the area of global oral health is very small compared to the highly diverse sectors of medical, pharmaceutical and development found in international public health. This lack of a critical mass is one of the aspects contributing to the low visibility of oral health internationally. There are, however, a number of deeper and more serious flaws that characterise the current global oral health community.

The sector of oral health experts, dental professionals, dental public health academics and the mainstream of international public health, medicine and general health are worlds apart. Symptoms of this disconnection include:

-

•

The exclusion of oral care in most primary health care systems

-

•

The lack of dental health systems research related to low- and middle-income countries

-

•

Continued adherence to workforce models monopolising the dentist’s role

-

•

Limited interest in health policy analysis

-

•

The lack of attention to oral care in the context of emerging social health insurance models.

None of the major international government agencies for Official Development Assistance have any recognisable health activities addressing oral diseases or prevention. There is also a poor correlation between existing practical and realistic evidence-based approaches, and policy tools to improve oral health; and the implementation and impact of such strategies on the broader population. This is evidenced by the failure to shift from individual clinical care to population-based preventive interventions, and the persistent misconception that appropriate oral care is necessarily costly and thus unaffordable for low- and middle-income countries.

The growing inequities between and within countries in terms of risk exposure, disease burden and access to care are symptoms of the limitations of the current global oral health actors, their governance structures, their vision and remit, scope of activities and their inability to interact effectively to address the situation.

A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSING POLITICAL PRIORITIES IN HEALTH

How is it possible to create critical momentum for oral health? What are the factors that determine political priorities in health? Shiffman and Smith proposed a framework for analysis of policy priority generation in global health, based on research on the Global Safe Motherhood Initiatitve7., 8., 9.. The PPF is based on the analysis of political power in four categories:

-

•

The power of ideas

-

•

The power of the issue

-

•

The power of the actors

-

•

The power of the political context.

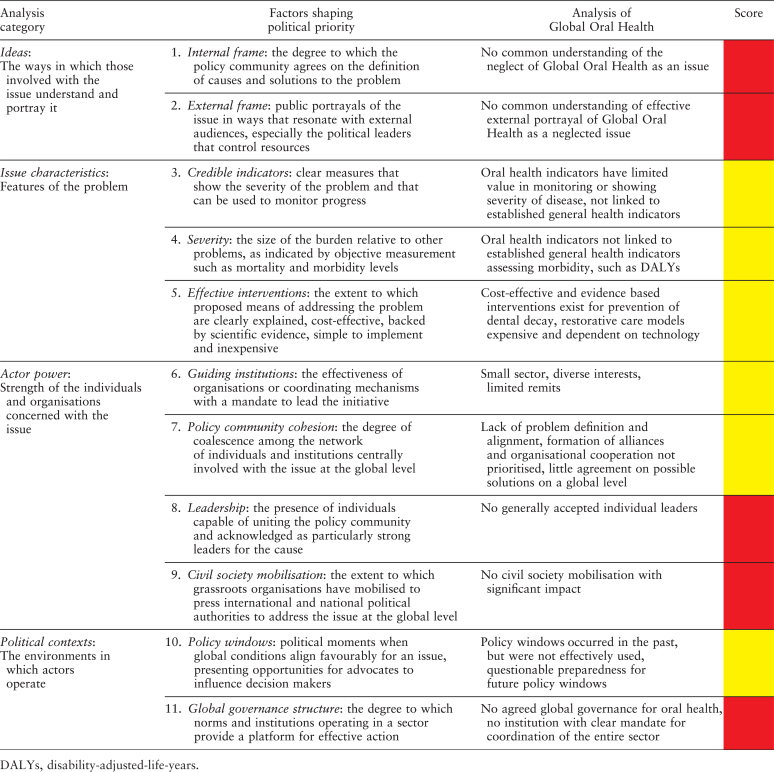

Furthermore, the framework defines 11 factors across the categories that shape political priority (Table 1). We will apply a modification of this framework to examine the case of global oral health, based on our profound knowledge of the sector, review of relevant literature, and long-term involvement with a variety of stakeholders and organisations active in global oral health. The modifications made to the framework are related to the order of the analysis categories and to the factors shaping the political priorities in order to be more relevant to the cause of global oral health.

Table 1.

Framework for analysis of factors shaping political priority (modified from Shiffman and Smith, 2007)

| Analysis category | Factors shaping political priority |

|---|---|

|

Ideas: The ways in which those involved with the issue understand and portray it |

1. Internal frame: the degree to which the policy community agrees on the definition of causes and solutions to the problem |

| 2. External frame: public portrayals of the issue in ways that resonate with external audiences, especially the political leaders that control resources | |

|

Issue characteristics: Features of the problem |

3. Credible indicators: clear measures that show the severity of the problem and that can be used to monitor progress |

| 4. Severity: the size of the burden relative to other problems, as indicated by objective measurement such as mortality and morbidity levels | |

| 5. Effective interventions: the extent to which proposed means of addressing the problem are clearly explained, cost-effective, backed by scientific evidence, simple to implement and inexpensive | |

|

Actor power: Strength of the individuals and organisations concerned with the issue |

6. Guiding institutions: the effectiveness of organisations or coordinating mechanisms with a mandate to lead the initiative |

| 7. Policy community cohesion: the degree of coalescence among the network of individuals and institutions centrally involved with the issue at the global level | |

| 8. Leadership: the presence of individuals capable of uniting the policy community and acknowledged as particularly strong leaders for the cause | |

| 9. Civil society mobilisation: the extent to which grassroots organisations have mobilised to press international and national political authorities to address the issue at the global level | |

|

Political contexts: The environments in which actors operate |

10. Policy windows: political moments when global conditions align favourably for an issue, presenting opportunities for advocates to influence decision makers |

| 11. Global governance structure: the degree to which norms and institutions operating in a sector provide a platform for effective action |

Table 2 summarises the results and relates the details to the modified analysis framework of Shiffman and Smith. The table also adds a scoring dimension to the analysis, where the colour red is used when the criteria of the framework factors are not sufficiently met, yellow if they are partially met, or green when a factor is fully met.

Table 2.

Political analysis results of the Global Oral Health sector

The power of ideas – global oral health as a neglected issue in international health

Framing is an important communication tool used in advocacy and related to the way an issue is portrayed and communicated, both internally and externally. The neglect of global oral health, however, is not defined as a problem and thus makes effective message framing impossible. The most basic agreed concept is the fact that oral health is important to general health and well-being. There is also agreement on the notion that good oral health is integral part of the basic human right to health10., 11., 12.. While these two fundamentals could be the basis for a common problem definition, the definition of neglect itself is missing.

Since the problem is not defined as an issue, different organisations or individuals have widely differing understandings of the concern. With this lack of problem definition it is difficult to achieve alignment and cohesion in policy approaches. The external framing of oral health as a neglected issue is scattered and anecdotal. While some of the international stakeholders and actors use the adjective ‘neglected’, they do so without a common understanding of the term and without anticipating how such messages resonate with the wider international health community. Here the term ‘neglected’ may evoke very different associations and is not self-explanatory for the uninitiated and certainly with those ignorant about the social determinants of oral health.

The power of the issue – why care for global oral health?

To oral health experts it seems obvious that oral health is important to human health. They often forget that the indicators used to assess oral health status and disease burden are not well-fitted to provide clear and transparent information about the true extent of the disease burden, are not suitable to monitor progress over time and are difficult to understand for policy makers and non-dental audiences. In addition, oral health indicators are not fully integrated into the general health indicator framework that is used and accepted by health decision makers, such as the disability-adjusted-life-years (DALY) concept. The existing DALY data for oral diseases are based on non-transparent assumptions and apparently do not take the episodic character of many oral diseases in to account13. In addition, it is not possible to transfer data from traditional oral health indicators into the DALY framework. Most oral health indicators are not connected at all to the indicators applied to monitor progress with the Millennium Development Goals, further contributing to the niche status of global oral health14.

Resulting from the lack of suitable indicators and the scarcity of relevant data, detailed and well-founded estimations of oral disease burdens relative to other disease groups are limited. This seriously hampers effective framing of messages and arguments in advocacy and does not allow for serious evidence-based justification to prioritise oral health.

The evidence for interventions addressing oral diseases exists, mainly for the prevention of dental decay by appropriate fluoride on a population basis15., 16., 17., 18., 19.. The traditional restorative technology-focussed approach of dentistry is clearly not affordable for the majority of health systems worldwide, resulting in the predominant model of provision of oral care through the private sector20. Although low-cost, realistic and scalable intervention packages exist, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO)-endorsed Basic Package of Oral Care, they have not gained sustained and widespread momentum, often because of professional’s resistance to delegation and task-shifting, and lack rigorous evaluation of implementation models21., 22.. The latter results in part from the low priority given to oral health research in general, and in part from the dental profession’s focus on restorative technology research that is well-funded by industry.

The power of actors – how powerful are they in global oral health?

The global oral health sector consists of a handful of international organisations with varying influence, such as the WHO, through its Global Oral Health Unit and its two Regional Advisers, the FDI World Dental Federation, the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), the International Federation of Dental Education Associations (IFDEA), and other international and national professional organisations, such as the International Association of Oro-maxillofacial Surgeons and national dental associations. Some of them are well resourced and nationally powerful. Yet, among all these organisations there is little alignment in terms of policy direction or cohesiveness of action. In real life the agendas of these organisations are determined completely independently of each other by fundamentally different constituencies with limited common interest. Furthermore, none of these organisations has a mandate for coordination of the entire sector and each of them protects its remit within a limited area that is closely guarded against external competing interests. Some organisations function simply as Trade Unions. Currently there is no strong leadership in the oral health community with the vision and ability to unite and inspire the entire sector.

The WHO provides some degree of authoritative policy guidance through various documents and resolutions, yet some of these documents were developed in a way that did not encourage participation and inclusion of other stakeholders23., 24., 25., 26., 27., 28.. Tangible and broad-scale action on most of them is missing due to lack of resources for follow-up and translation into regional and national policies and action plans that have an impact at the local level.

The FDI World Dental Federation has gained some momentum in global oral health. While the moral prerogative to engage in ‘leading the world to optimal oral health’ is at the core of the FDI’s vision and missions, the organisation is often limited due to internal politics and conflicting interests within its constituent base of private practitioner associations29., 30., 31.. IADR and IFDEA recognise and emphasise the need to engage in global oral health advocacy to reduce inequalities, but such activities are only a small part of their overall remit5., 32., 33..

An organised international civil society for global oral health, apart from national dental associations, does not exist. Some high-income countries, such as the USA or the UK have national civil society stakeholders with considerable power, such as foundations or national oral health initiatives; yet in the absence of a uniting and coherent problem definition their activities are not well aligned. Most of these organisations are initiated, led and funded by the dental community in the largest sense; true patient organisations advocating for patient rights, access to care or basic coverage are virtually absent on the national and international scene. The sector of ‘dental aid organisations’, comprising NGOs of industrialised countries giving assistance to low- and middle income countries is mostly underdeveloped, uses outdated and inappropriate approaches and plays no significant role internationally34., 35..

The role of the oral care industry in promoting oral health has largely been neglected in academic research. The handful of global multinational companies are a distinctive force in global oral health, yet their characteristics, agendas and actions are poorly documented and analysed. Their research and consumer-oriented products have contributed greatly to the global decline of dental decay over the last 50 years36. Recently, activities that are broadly summarised under the title ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ reached a limited level of attention, although significant and large-scale Public–Private Partnerships are missing. The global budgets of such companies combined largely exceed the budgets of the WHO and the health budgets of all least-developed countries put together, yet the potential that lies in purposeful partnerships and sustained involvement in global public health remains untapped37., 38..

The power of political context – creating, using and anticipating opportunities

The sector of global oral health suffers from a lack of analysis, connection and insight into political contexts. Unlike other areas of international health, there are no think-tanks or institutions for policy and political analysis. Policy windows on the international level do not come often, and if they arise it requires a degree of coalescence between stakeholders to use them effectively. The adoption of an action plan on oral health by the 60th World Health Assembly in 2007 could have been such a policy window if efforts to exploit the opportunity would have been planned ahead, coordinated and agreed between the various international and national stakeholders, based on a common understanding and a participatory agenda related to promoting oral health39. While the first set of Global Goals for Oral Health by 2000 created some momentum through a competitive process to reach the targets, the current set of Global Goals by 2020 has not reached critical momentum. But there are also examples of successful policy windows40., 41., 42.. The sad case of Deamonte Driver, a boy dying from preventable dental infection in the USA, created an opportunity for the American Dental Association and others in advocating for improved child oral health care43., 44.. Preparedness for such policy windows is essential because they usually require a quick reaction.

MAKING GLOBAL ORAL HEALTH A POLICY PRIORITY – A ROADMAP

All four power categories of the analysis framework showed essential shortcomings and weaknesses ranging from the most basic matters, such as defining the issue in an agreed way, to complex and multi-levelled issues related to appropriate data collection and agreement on adequate solutions. The analysis does not pretend to be a comprehensive assessment of diverse realities. The model applied was appropriate for the initial analysis of the factors that currently limit the global oral health community; but other, more sophisticated methodologies may reveal further important aspects.

This overall diagnosis of the area of global oral health should be seen as a starting point for further investigation and a candid and honest assessment of the present status of the sector. The fact that no area of power in global oral health scored green and five out of the eleven categories scored red may be difficult to understand or accept for some; but it will hopefully open a constructive international debate on these matters. Only with such a baseline it will be possible to develop a roadmap for improvements in some or all areas analysed, which should be in the best interest of all those involved in the sector.

We believe that only with a fundamentally new approach and through joint effort will it be possible to give global oral health a new and purposeful orientation and impetus. The details of such an approach will need to be determined among all involved and it will be essential to base efforts on an agreed problem definition. The need to address the growing inequities may be a realistic starting point; as well as the recognition that the traditional dichotomous division of the world into developed and developing countries is no longer real, nor helpful. Health and oral health inequities in a globalised world follow social gradients that are largely determined outside of the oral health arena, and they go across countries and different populations within countries45., 46..

The consequences of such new thinking are fundamental. The health equity debate will no longer focus on disparities between countries or within countries, but between socio-economic groups, the determinants of their health and ways to address them. Such thinking will lead to an alignment of agendas because all stakeholders, be it in oral health or in the wider international health arena, will discover broad areas of common interest that may be tackled with similar and integrated approaches, irrespective of the average income classification of the country.

CONCLUSION

Political priority for global oral health is low, resulting from a set of complex issues deeply rooted in the current global oral health sector, its stakeholders and their remit, the lack of coherence and coalescence; as well as the lack of agreement on the problem, its portrayal and possible solutions. This paper can only be a starting point for a long overdue, broad and candid international analysis of political, social, cultural, communication, financial and other factors related to better prioritisation of oral health. Such a discussion will reveal further painful truths, but without such an analysis and resulting concerted action the global inequities in oral health will grow and increasingly impact on health systems, development and, most importantly, human lives.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361:2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samb B, Evans T, Dybul M, et al. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 2009;373:2137–2169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravishankar N, Gubbins P, Cooley RJ, et al. Financing of global health: tracking development assistance for health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet. 2009;373:2113–2124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, American Dental Association, American Dental Education Association, FDI World Dental Federation, International Association for Dental Research, Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization . American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, American Dental Association, American Dental Education Association, FDI World Dental Federation, International Association for Dental Research, Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2005. Oral Health – Integration and Collaboration. Testimony for the 2005 Global Health Summit. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenspan D. Oral health is global health. J Dent Res. 2007;86:485. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaglehole R, Benzian H, Crail J, et al. FDI World Dental Education Ltd & Myriad Editions; Geneva & Brighton: 2009. The Oral Health Atlas: Mapping A Neglected Global Health Issue. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiffman J, Smith S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet. 2007;370:1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiffman J. Center for Global Development Brief; 2007. Generating political priority for public health causes in developing countries: implications from a study on maternal mortality. Available from: http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/13821/. Accessed 20 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiffman J. A social explanation for the rise and fall of global health issues. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:608–613. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobdell MH. Health as a fundamental human right. Br Dent J. 1996;180:267–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson M. Health as a human right: implications for the dental profession. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12(Suppl. 1):9–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueno RE, Moyses SJ, Moyses ST. Millennium development goals and oral health in cities in southern Brazil. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A et al. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003: CD002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Beirne P, Forgie A, Worthington HV et al. Routine scale and polish for periodontal health in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007: CD004625. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Watt RG. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:711–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health, Population Health and Wellness . British Columbia Ministry of Health; Vancouver: 2006. Evidence Review: Dental Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health . Department of Health; London: 2007. Delivering Better Oral Health. An Evidence-Based Toolkit for Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee R, Sheiham A. The burden of restorative dental treatment for children in Third World countries. Int Dent J. 2002;52:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frencken JE, Holmgren C, van Palenstein Helderman W. WHO Collaborationg Centre for Oral Health Care Planning and Future Scenarios, University of Nijmengen; Nijmengen, the Netherlands: 2002. Basic Package of Oral Care (BPOC) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chher T, Hak S, Courtel F, et al. Improving the provision of the Basic Package of Oral Care (BPOC) in Cambodia. Int Dent J. 2009;59:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen PE. Challenges to improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Int Dent J. 2004;54:329–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen PE, Lennon MA. Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:319–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen PE. The burden of oral disease: challenges to improving oral health in the 21st century. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen PE. Priorities for research for oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Health. 2005;22:71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health – World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 2008;58:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benzian H, Nackstad C, Barnard JT. The role of the FDI World Dental Federation in global oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:719–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benzian H, Weber G. Public health activities shaping the profile of the FDI World Dental Federation. Developing Dent. 2009;10:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conrod B, Cohen L. Transforming dentistry’s commitment to global oral health. J Canadian Dent Assoc. 2007;73:653–655. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. A global theme poverty and human development. J Dent Res. 2007;86:917–918. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donaldson ME, Gadbury-Amyot CC, Khajotia SS, et al. Dental education in a flat world: advocating for increased global collaboration and standardization. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:408–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benzian H, Gelbier S. Dental aid organisations: baseline data about their reality today. Int Dent J. 2002;52:309–314. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mouradian WE. Band-aid solutions to the dental access crisis: conceptually flawed-a response to Dr. David H. Smith. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1174–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies RM, Ellwood RP, Davies GM. The contribution of industry to the decline in dental caries. Dent Update. 2001;28:140–142. doi: 10.12968/denu.2001.28.3.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexander D, Clarkson J, Buchanan R, et al. Exploring opportunities for collaboration between the corporate sector and the dental education community. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12(Suppl. 1):64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buse K, Harmer AM. Seven habits of highly effective global public-private health partnerships: practice and potential. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Oral Health: Action Plan for Promotion and Integrated Disease Prevention. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA60. R17, 2007.

- 40.FDI World Dental Federation Global goals for oral health in the year 2000. Int Dent J. 1982;32:74–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aggeryd T. Goals for oral health in the year 2000: cooperation between WHO, FDI and the national dental associations. Int Dent J. 1983;33:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leopold CT, Mander C, Utting C, et al. The World Health Organisation goals for oral health: a progress report. Community Dent Health. 1991;8:245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Dental Association. American Dental Association Statement on the death of Deamonte Driver, 2 March 2007. Available from: http://www2.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=104&STORY=/www/story/03-02-2007/0004538384&EDATE=. Accessed 20 April 2010

- 44.Edelstein BL. Putting teeth in CHIP: 1997–2009 retrospective of congressional action on children’s oral health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hobdell MH, Oliveira ER, Bautista R, et al. Oral diseases and socio-economic status (SES) Br Dent J. 2003;194:91–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809882. discussion 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernabe E, Hobdell MH. Is income inequality related to childhood dental caries in rich countries? J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:143–149. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]