Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess the knowledge of future dentists of the United Arab Emirates on risk and non-risk factors for oral cancers and correlate it with their own tobacco use, whether they assess their patients’ tobacco use and their opinion about the relation of oral cancer and smokeless tobacco use. Methods: A total of 270, first- to fifth-year undergraduate dental students who consented to participate in the study filled in a questionnaire enquiring about their knowledge of oral cancer risk factors. A score of oral cancer risk factor knowledge was calculated for each participant based on their correct answers. Results: Eighty-three per cent of participants identified the use of tobacco as a risk factor for oral cancer, 52% identified old age, 45.6% knew about low consumption of fruits and vegetables and 74.4% of students could correctly identify use of alcohol as a risk factor for oral cancer. A significant association was found between being a current and previous tobacco user and having low knowledge of risk factors score (P = 0.015). No significant associations were found between the year of study in the dental college, gender, nationality and knowledge of oral cancer risk factor scores. Conclusion: This study showed an apparent lack of knowledge of oral cancer risk factors among dental students that may later result in a deficiency in integrating optimal oral cancer diagnostic procedures in their practices. There is an urgent need to enhance the oral cancer curricula in oral cancer education and clinical training in oral cancer prevention and examination for dental students.

Key words: Dental students, oral cancer risk factors, dental education

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 90% of cancers affecting the oral cavity are squamous cell carcinomas, mainly found in the lip, tongue, floor of the mouth, gingiva, buccal mucosa and palate1. Tobacco and alcohol use are the primary risk factors for oral cancer in patients over the age of 45 years2. Low consumption of fruits and vegetables, exposure to the sun, infection with Human papilloma virus (HPV) are some of the other risk factors for oral cancers3., 4., 5..

In the USA the 1996 National Strategic Planning Conference for the Prevention and Control of Oral and Pharyngeal Cancer, states that not only should health-care professionals be aware of the factors that increase the risk for oral cancer, they should also know how to examine patients with suspicious oral lesions6. Previous studies have shown that health-care professionals, including dentists, hygienists, nurses, physicians and dental and medical students lack adequate knowledge of oral cancer, fail to incorporate examination of the oral cavity for suspicious lesions and do not perform oral cancer examination routinely7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12..

Death rate from oral cancer per 100,000 is reported as 3.15 in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), ranking 134 in the world13.

According to World Health Organisation (WHO) demographics 18% of UAE adults are smokers14. Findings from the 2005 WHO, UAE Global School-based Student Health Survey (UAE-GSHS-2005) conducted on 15,634 students showed that, overall, 12.7% of students used a type of tobacco product15.

There is no data known to us on UAE dental students’ knowledge of oral cancer risk and non-risk factors.

The purpose of this study was to assess the knowledge of future dentists of the UAE on risk and non-risk factors for oral cancers and correlate it with their own tobacco use, to determine whether they assess their patients’ tobacco use and to discover their opinion about the relation of oral cancer and the use of a smokeless tobacco product.

METHODS

A convenience sample of first- to fifth-year undergraduate dental students of Ajman University of Science and Technology in Ajman, UAE, were approached during February 2010. The total number of questionnaires distributed was 350 from which a total of 270 (140 males, 130 females) agreed to participate (response rate 77%). Those who agreed to participate in the study gave their written consent and completed the self administered questionnaire. Written consent was obtained from the parents of students who were under 18 years old. The Research Committee of College of Dentistry, Ajman University of Science and Technology gave ethical approval for the study. The study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Questionnaires were distributed with the permission of the deanship of the college after a class. No personal identification information was obtained from the students. Their age range was 17–26 years. A higher percentage of male students participated in the study than female students and greatest percentage of participants were final-year students. The participation of non-Emirati Arab students’ was higher than Emirati and non-Arab students. The 19-item questionnaire included six questions inquiring about the student’s own tobacco use, whether they assess their patients’ tobacco use and their opinion about the relation of oral cancer and smokeless tobacco; this created our six selected tobacco variables. In addition, 13 questions were asked to assess the knowledge of the oral cancer risk factors (Table 1), six questions addressed real risk factors (those supported by research) and seven questions addressed non-risk factors (those not supported by research).

Table 1.

Real risk factors (those supported by research), and non-risk factors (those not supported by research) for oral cancer

| Real risk factors: | Non-risk factors: |

|---|---|

| Use of tobacco | Hot beverages and food |

| Previous oral cancer lesion | Use of spicy foods |

| Use of alcohol | Obesity |

| Older age | Poor oral hygiene |

| Lip cancer related to exposure to sun | Familial clustering |

| Low consumption of fruits and vegetables | Poor-fitting dentures |

| Family history |

We calculated the index of knowledge of oral cancer risk factors (a number ranging from 0 to 13) by giving a score of 1 for each correct response to the 13 items regarding risk factors for oral cancer. Based on the knowledge index, we classified students into one of the three categories: high score (10–13), medium score (7–9) and low score (0–6). Microsoft Excel was used to enter the completed questionnaires into a database. We generated descriptive statistics for all questions and examined the frequency distribution and percentages of all answers.

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in the scores according to gender, nationality, year of study and the six selected tobacco variables. We set the statistical significance level to P < 0.05. All the analyses were carried out using spss V. 17 software (University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE).

RESULTS

Table 2 summarises the socio demographic characteristics of the participating students and Table 3 shows the distribution of the students’ responses to the first six questions about tobacco use and attitudes. Analysis showed that 52.6% of participants were current and previous tobacco users and 64% of the students assess patients’ type and amount of tobacco use.

Table 2.

Distribution of students according to the year of study, nationality and gender

| Year of study | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1st year | 45 (16.7) |

| 2nd year | 63 (23.3) |

| 3rd year | 47 (17.4) |

| 4th year | 45 (16.7) |

| 5th year | 70 (25.9) |

| Nationality | |

| Emirati | 64 (23.7) |

| Non-Emirati Arab | 153 (56.7) |

| Non-Emirati non-Arab | 53 (19.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 140 (51.9) |

| Female | 130 (48.1) |

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage of the students who responded positively to the selected tobacco variables

| Selected tobacco variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Students who are tobacco users | 81 (30) |

| Students who are previous tobacco users | 61 (22.6) |

| Students who assess patient’s previous tobacco history | 192 (71.9) |

| Students who assess patient’s type and amount of tobacco use | 173 (64) |

| Students who think cigarette smoking places person at higher risk for oral cancer than using chewing tobacco | 205 (76) |

| Students who think chewing tobacco lesions generally resolve after discontinuing use | 159 (59) |

The percentage of correct and incorrect answers to the oral cancer risk factors and non-risk factors questions are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Regarding knowledge of oral cancer risk factors, 83% of the students could identify use of tobacco as a real risk factor for oral cancer. Only 52% could correctly identify old age as a risk factor for oral cancer, 45.6% of students knew that low consumption of fruits and vegetables is a risk factor, 69.6% knew that lip cancer related to sun exposure and 74.4% could correctly identify use of alcohol as a risk factor for oral cancer. Of the participants, 84.4% knew that having had a previous oral cancer lesion is a risk factor for oral cancer.

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct (dark tinted columns) and incorrect (light tinted columns) answers of dental students to the oral cancer risk factors questions.

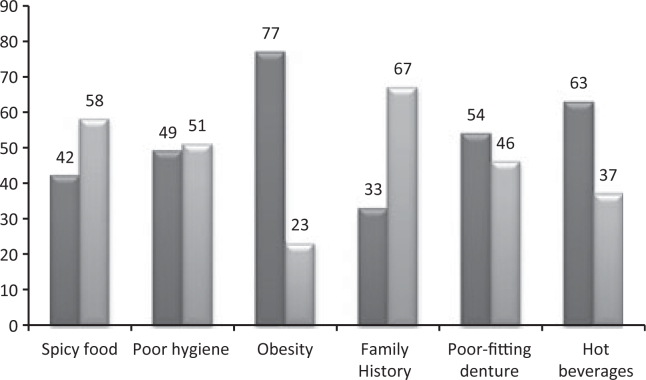

Figure 2.

Percentage of correct (dark tinted columns) and incorrect (light tinted columns) answers of dental students to the oral cancer non-risk factors questions.

Regarding non-risk factors, almost half the students falsely thought that poor oral hygiene is a risk factor; similarly, only 54.4% identified poor-fitting dentures as a non-risk factor. Of respondents, 41.9% and 63%, respectively, knew that consumption of spicy food and hot beverages and food are not real risk factors for oral cancer. Obesity was identified as non-risk factor by 77.4% but only 33% knew that familial clustering is not a real risk factor.

No significant associations were found between the year of study in the dental college, gender, nationality and knowledge of oral cancer risk factor scores. There was a gradual increase in the medium risk factor knowledge score and a decrease in the low knowledge score with increasing year of study, but this was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of students according to year of study and oral cancer risk factor knowledge score

| Year of study | Oral cancer risk factor knowledge score | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0–6) | Medium (7–9) | High (10–13) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 1st year | 12 (26.7) | 27 (60) | 6 (13.3) | 45 (100) |

| 2nd year | 22 (34.9) | 38 (60.3) | 3 (4.8) | 63 (100) |

| 3rd year | 10 (21.3) | 31 (66) | 6 (12.8) | 47 (100) |

| 4th year | 7 (15.6) | 29 (64.4) | 9 (20) | 45 (100) |

| 5th year | 13 (18.6) | 50 (71.4) | 7 (10) | 70 (100) |

| Total | 64 (23.7) | 175 (64.8) | 31 (11.5) | 270 (100) |

Table 5 shows the associations between the knowledge index score and the six selected tobacco variables. There was significant association between being a tobacco user and risk factor knowledge score. Those in the low-score category tended to be smokers; 33% of students who themselves were tobacco users scored low while 20% of non-users scored low (P = 0.024).

Table 5.

Association between the risk factor knowledge index score and six selected tobacco variables

| Knowledge of risk factors score | Total n | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0–6) | Medium (7–9) | High (10–13) | ||||

| Are you any kind of tobacco product user? | Yes | 27 (33.3%) | 43 (53.1%) | 11 (13.6%) | 81 | 0.024* |

| No | 37 (19.6%) | 132 (69.8%) | 20 (10.6%) | 189 | ||

| Are you a former tobacco user? | Yes | 22 (36.1%) | 36 (59%) | 3 (4.9%) | 61 | 0.15 |

| No | 42 (20.1%) | 139 (66.5%) | 28 (13.4%) | 209 | ||

| Do you assess patients previous tobacco use when taking a medical history? | Yes | 41 (21.1%) | 128 (66%) | 25 (12.9%) | 194 | 0.197 |

| No | 23 (30.3%) | 47 (61.8%) | 6 (7.9%) | 76 | ||

| Do you assess type and amount of tobacco use when taking a medical history? | Yes | 29 (16.8%) | 120 (69.4%) | 24 (13.9%) | 173 | 0.001* |

| No | 35 (36.1%) | 55 (56.7%) | 7 (7.2%) | 97 | ||

| Do you think cigarette smoking places person at higher risk for oral cancer than using chewing tobacco? | Yes | 46 (22.2%) | 138 (66.7%) | 23 (11.1%) | 207 | 0.497 |

| No | 18 (28.6%) | 37 (58.7%) | 8 (12.7%) | 63 | ||

| Do you think chewing tobacco lesions generally resolve after discontinuing use? | Yes | 46 (28.6%) | 95 (59%) | 20 (12.4%) | 161 | 0.041* |

| No | 18 (16.5%) | 80 (73.4%) | 11 (10.1%) | 109 | ||

Statistically significant.

Similarly, a significant association was found between being previous tobacco user and having a low knowledge of risk factors score (P = 0.015). Those in the high category of risk factor knowledge score tended to be non-smokers (13% of non-users scored high whereas only 5% of tobacco users scored high).

A highly significant association was found between the knowledge of risk factor score and students’ commitment to asking their patients about the type and amount of tobacco use while taking a medical history. While 36% of students who did not assess type and amount of tobacco use scored low, 7% of them scored high. Similarly, 17% of those who asked about the type and amount of tobacco use scored low and 14% of them scored high (P = 0.001).

There was a significant association between the students’ response to whether tobacco lesions resolve or not after discontinuing use and their risk factor knowledge score: 29% of those responding ‘yes’ scored low and only 17% of those who responded ‘no’ scored low (P = 0.04).

DISCUSSION

Our study was limited to a cross-sectional survey of 270 dental students studying in one dental school in the UAE; therefore it should not be generalised for all dental schools of this country.

Some aspects of the results of our study parallel those in previous surveys’ results done among dentists and dental students7., 8.. More than 80% of students in our survey correctly identified tobacco use as a real risk factor and 74.4% identified alcohol as a risk factor. Carter et al. 9, in a study assessing general medical and general dental practitioners’ oral cancer awareness, found similar results among dentists. In their study only < 20% of dentists could identify other risk factors. Our results regarding knowledge of low consumption of fruits and vegetables as a risk for oral cancer was similar to those of previous surveys8., 10..

Almost half of the dental students’ knowledge in our study regarding non-risk factors was incorrect when compared with a previous study in which 60–70% of students were reported as knowledgeable about non-risk factors10, indicating that half of our subjects were misinformed about non-risk factors. However, this result of ours was comparable with the results of a survey done by Yellowitz et al. 8 on practicing dentists who found that almost 70% knew that obesity is not a risk factor and only 50% knew poor oral hygiene is not a risk for oral cancer.

For risk factor knowledge scores and academic year, we did not find the expected statistically significant association (i.e. an increase in the knowledge scores with year of study). In contrast, Boroumand et al. 16, in their study conducted among Maryland dental students, found that knowledge of oral cancer was low among freshmen when compared with other classes. It is worth mentioning that regardless the year of study, the majority of students (65%) had medium knowledge scores; only 11.5% of students had high knowledge scores. This finding shows an inadequate level of knowledge of oral cancer of our subjects, which is comparable to some of the US dental schools and suggests a need for greater emphasis on oral cancer knowledge in curricula of dental schools11., 12., 16..

In our study 22.6% of dental students who participated were ex-smokers and 30% were smokers. This high percentage of smoking among dental students is alarming. It was noted that, in lower knowledge score category, the number of students who were themselves smokers and ex-smokers was greater than the number of non-smokers. It is clear from this study that smokers have less knowledge of oral cancer and they have less interest in their patients’ smoking history and tobacco use. Students who were non-smokers tended to inquire more about their patients smoking status and tobacco use. It is logical to assume that students who are keen to assess patient’s type and amount of tobacco use while taking medical history would have higher knowledge of risk factors score. In the UAE smoking is now strictly prohibited by law indoors and outdoors at universities. Hopefully, this restriction will help to reduce the number of smokers among the university students.

Moreover, it has been demonstrated in the literature that dental students in their clinical practice perform the procedures that they have been routinely taught during their clinical training. Our data also showed the positive association between having greater knowledge about oral cancer and the dental students’ actions to assess oral cancer risk factors. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate an emphasis on oral cancer prevention and diagnosis in the education of dental students. When the oral cancer knowledge of graduating dental students is increased, the number of dental practitioners who are knowledgeable and competent in providing their patients with the appropriate oral cancer prevention and examination procedures will be increased.

CONCLUSION

This study showed an apparent deficiency of knowledge about oral cancer risk factors among dental students, which may later cause an inadequacy in integrating optimal oral cancer diagnostic procedures in their practices. There is an urgent need to enhance curricula on oral cancer education and clinical training in oral cancer prevention and examination for dental students.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank dental students of Ajman University of Science and Technology who volunteered to participate in our study.

Competing interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silverman S., Jr . 4th ed. Decker; Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: 1998. Oral cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomar SL. Dentistry’s role in tobacco control. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(Suppl):30S–35S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman S., Jr Demographics and occurrence of oral and pharyngeal cancers: the outcomes, the trends, the challenge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(Suppl):7S–11S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Touger-Decker R, Mobbley CC, American Dietetic Association Position of the American Dietetic Association: Oral Health and Nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:615–625. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erdmann J. Recent studies attempt to clarify relationship between oral cancer and human papilloma virus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:638–639. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.9.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Dental Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Dental Research/National Institutes of Health. Proceedings: National Strategic Planning Conference for the Prevention and Control of Oral and Pharyngeal Cancer; August 7-9,1996 Chicago. Available from: www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/pdfs/proceedings.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2011

- 7.Yellowitz JA, Goodman HS. Assessing physicians’ and dentists’ oral cancer knowledge, opinions and practices. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:53–60. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellowitz JA, Horowitz AM, Drury TF, et al. Survey of U.S. dentists’ knowledge and opinions about oral pharyngeal cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:653–661. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter LM, Ogden GR. Oral cancer awareness of general medical and general dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2007;203:E10. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannick GF, Horowitch AM, Drury TF, et al. Assessing oral cancer knowledge among dental students in South Carolina. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:373–378. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burzynski NJ, Rankin KV, Silverman S, Jr, et al. Graduating dental students’ perceptions of oral cancer education: results of an exit survey of seven dental schools. J Cancer Educ. 2002;17:83–84. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rankin KV, Jones DL, McDaniel RK. Oral cancer education in dental schools: survey of Texas dental students. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11:80–83. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Rankings, Live longer live better. Available from: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/middle-east/oral-cancer-cause-of-death. Accessed 31 March 2011

- 14.World Health Organization. Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI), The Tobacco Atlas, 1st edn. Part six: World Tables. Table A: The Demographics of Tobacco; 2002. http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas40pdf. Accessed 31 March 2011

- 15.2005 United Arab Emirates Global School-based Student health survey (UAE-GSHS-2005). Available from: www.who.int/entity/chp/gshs/2005%20UAE%20Questionnaire.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2011

- 16.Boroumand S, Garcia AI, Selwith RH, et al. Knowledge and opinions regarding oral cancer among Maryland dental students. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:85–91. doi: 10.1080/08858190701821238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]