Abstract

Objectives: To document and analyse the various dental ailments reported and treatments administered during the 2010 Commonwealth Games, held in Delhi, India, based on the treatment registries at the dental clinic in the medical centre in the Commonwealth Games Village and at the primary nodal centre. Methods: A retrospective analysis of dental treatments administered at the Commonwealth Games Village medical centre, from 23 September to 16 October 2010, was conducted. Cases reported referred to athletes, their family members and ancillary staff. A total of 342 instances of various treatments were reported. Results: Patients reporting dental complaints and/or receiving dental treatment represented 5.3% of games participants and ancillary personnel. The largest groups of patients categorised by country of origin came from India, the host nation, followed by Kenya and Nigeria. Most of the interventions were prescription-based and included medications for dental pain and infections, followed by restorative or conservative procedures. Conclusions: A standardised guideline on the minimum requirements for a dental clinic for the Commonwealth Games should be established by the Commonwealth Federation.

Key words: Dentistry, Commonwealth Games, sports dentistry

INTRODUCTION

The 19th Commonwealth Games were held in Delhi, India, in 2010, with much fanfare; the Games showcased India as a nation capable of hosting an event of such magnitude. Sporting events of these proportions require the input of a great number of individuals, including athletes, officials and a supporting workforce, in order to result in a successful endeavour. Providing these individuals with medical support is an important aspect of the ancillary infrastructure. The medical centre established at the Commonwealth Games Village (CGV) was designed to fulfil this purpose.

It was proposed that a dental support centre would be integrated into the proposed medical centre in the CGV. This decision was based upon findings in an extensive study conducted by Piccininni and Fasel1, who reviewed the literature on the various dental services provided at the Olympic Games from 1932 to the Athens Olympics in 2004.

Although the Commonwealth Games have been held for over 80 years, no useable data on dental services provided at previous Commonwealth Games events are available. The previous host city, Melbourne, did not provide in-house dental clinic services and patients with dental complaints were referred to nearby dental hospitals2. A dental clinic was thought to be an important addition to the medical centre proposed for the Games to be held in Delhi and the best of facilities were incorporated into the set-up.

Overview of the dental clinic at the CGV in 2010

The dental clinic at the CGV was a state-of-the-art facility in which modern dental services could be provided with ease. The set-up included two fully automatic dental chairs, one radiovisiography unit, one portable radiographic gun, autoclave units, torque control motors, apex locators, and built-in and stand-alone suction apparatus. The entire clinic was designed in a modular format, which facilitated the maintenance of a clean and sterile environment. The dental centre was also temperature- and humidity-regulated for the comfort of patients. The highest quality of care was provided to patients using the most recently available facilities.

The dental clinic functioned for 12 hours per day and was staffed continually by specialists from various dental specialties. The team comprised an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, an endodontist, a periodontist, two community dentists and a general dental surgeon. These were supported by dental hygienists, a dental nurse, and chair assistants. The clinic functioned from 08.00 hours to 20.00 hours. Outwith these hours, patients were referred directly to the primary nodal centre, in which an oral and maxillofacial surgeon was available 24 hours per day.

METHODS

A retrospective evaluation of data sourced from the CGV dental clinic case registry and the primary nodal centre dental registry was conducted. A total of 342 patients were found to have reported to the dental centre. The spectrum of services provided included both temporary and permanent restorations, root canal treatments, oral prophylaxis, periodontal curettage, crown cementations, removable partial denture fabrication, sedative dressings, extractions, wisdom tooth removal, incision and drainage, and maxillofacial injury management.

Of the 71 countries participating in the Games, patients from 42 countries reported to the dental clinic. Treatments were classified into various categories including oral diagnoses and prescriptions, oral prophylaxis procedures, temporary restorations, permanent restorations, surgical procedures (i.e. wisdom tooth removal, suturing of lacerations, incision and drainage of dental abscess and space infections, splinting of dentoalveolar fractures), routine extraction of teeth, root canal treatment, and cases referred to the primary nodal centre.

Oral prophylaxis, for which an ultrasonic scaler was used, was performed in a total of 24 patients. Temporary restorations using sedative dressings were performed in 43 patients. Permanent restorations required as a result of carious dental lesions or because previous restorations were fractured were performed in 24 patients. A total of 14 surgical procedures were performed. Five of these referred to incision and drainage, in most of which the abscess was drained by the intraoral route. The other nine instances of surgical treatment comprised two cases of primary closure of various intraoral lacerations caused by sporting injuries, two cases of splinting of dentoalveolar fractures, one case of haematoma drainage, and four cases of soft tissue contusions managed by medication and cold compression.

In five cases extractions were mandatory as the teeth were not salvageable by conservative dental procedures. Endodontic or root canal therapies were performed in nine patients in whom sedative restorations failed to alleviate symptoms or irreversible pulpitis was found. Only 10 patients were referred to the primary nodal centre for the management of advanced dental procedures, which included difficult wisdom tooth removal, and refabrication or repair of removable partial dentures. Two dental emergency cases were directly referred from sports venues. These included a case of luxated anterior teeth that occurred during a boxing event and required the extraction of the teeth, and a case of lower labial vestibular laceration sustained during a rugby match, which required primary closure. One athlete suffered a fracture of the zygomatic bone sustained in a game of netball and underwent computed tomography at the nodal centre to confirm the diagnosis, but did not undergo any treatment for the condition.

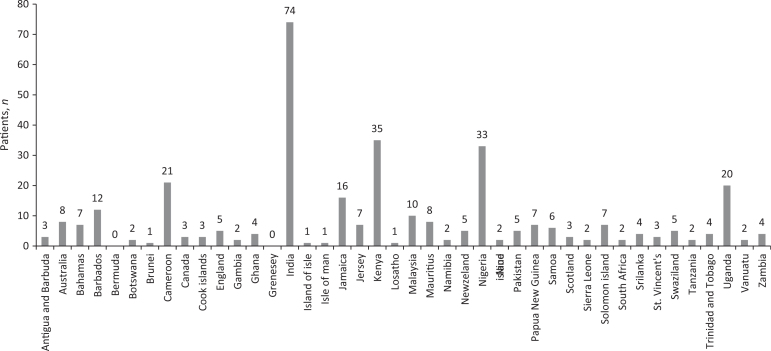

Of the 42 countries from which patients reported to the dental clinic with dental problems that varied in nature from elective to emergency cases, the host nation India was home to the largest group (n = 74), followed by Kenya (n = 35) and Nigeria (n = 33).

RESULTS

The Commonwealth Games involved a total of 6,500 athletes and ancillary personnel3, from among whom the CGV dental clinic and the nodal centre treated 342 patients, representing 5.3% of all personnel (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patterns of reporting to the dental centre at the Commonwealth Games Village, 2010, and interventions performed, by country of patient.

A total of 21.6% of dental patients came from the host country and underwent procedures consisting mostly of elective and minimal emergency procedures. Reporting and treatment percentages of participants from Kenya and Nigeria were 10.2% and 9.6%, respectively (Figure 2). Reporting frequencies of patients from the developed nations were very low or nil in some cases as a result of the better standards of oral hygiene and care afforded in these countries.

Figure 2.

Reporting incidences at the dental centre at the Commonwealth Games Village, 2010, by country of patient.

The most commonly performed treatments were oral diagnoses and the administration of medication for dental pain and infections; these accounted for 58.1% of all treatments administered. Conservative procedural treatments comprising temporary or permanent restorations and root canal treatments represented 22.2% of treatments administered. Oral prophylaxis and dental surgical procedures accounted for 8.2% and 4.7% of treatments, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatments administered at the dental centre at the Commonwealth Games Village, 2010.

DISCUSSION

The CGV dental polyclinic was set up according to recommendations proposed by Piccininni and Fasel1; these guidelines were suggested for the Olympic Games and were not followed in strict accordance as no previous statistics on dental treatment reporting patterns at Commonwealth Games events were available.

The set-up was designed in order to ensure that time loss would be minimal so that athletes could return to competitive events or training as soon as possible. For this purpose, technologies such as radiovisiographs, apex locators, portable radioguns and rotary endomotors were used as part of time-saving strategies intended to allow for precise and accurate diagnosis and treatment and to cause minimal discomfort to patients attending the clinic.

The predefined approach required treatment to be as conservative as possible because aggressive or invasive treatments might interfere with an athlete’s performance. This approach was also selected with the intention of causing minimal iatrogenic trauma as trends show that dental treatment procedures carried out at the various Olympic Games have become more conservative in nature over time1.

As anticipated, treatments performed at the CGV dental clinic tended to be conservative in nature, with 76 patients undergoing temporary or permanent restorations and root canal treatments and only five patients undergoing extractions (Figure 3).

An article on the role of dentistry for the US Olympic Committee pointed out that: ‘Every pre-competition screening turns up several athletes with severely decayed or abscessed teeth.’4 Hence, a preliminary screening might have resulted in a higher reporting percentage, but was not performed because a screening of such magnitude was not considered possible given the numbers of athletes and delegates.

The article also stated that elite athletes may be more susceptible to dental emergencies because many of them belong in the 18–23-year-old age group, among whom wisdom teeth are likely to cause dental distress.4 The author further suggested: ‘Dental neglect could mean that all the years of sweat and sacrifice leading to international competition can be compromised unnecessarily at the moment of truth by a tooth abscess or other dental emergency.’4

The fact that patients from the host nation represented the largest dental patient group reflects the sheer number of athletes and delegates associated with the Indian contingent, as well as the volunteers who reported for treatment, numbers of whom could not be accounted for. The numbers of the next largest patient groups, from Kenya and Nigeria, were substantially lower than that of the host country (Figure 2). Patients from the participating developed nations, in which standards of dental care are generally better than those in less developed countries, reported for treatment only in dental emergencies, either as a result of reluctance to receive dental care in a foreign nation and misgivings concerning the standards of care provided, or because better overall dental health precluded any requirements for intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

A standardised guideline taking into consideration the minimum requirements for a dental clinic at the Commonwealth Games should be established by the Commonwealth Federation. Dental problems in athletes are a reality and dental problems of any nature may affect an athlete’s performance, thereby also affecting his or her country’s tally of medals. Therefore, the provision of prompt and effective treatment is necessary and this can only be provided if a fully supported dental clinic is located close to or preferably within the CGV complex.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire Commonwealth Games medical team for its general support. This report was prepared in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was passed by the ethics board of the Maulana Azad Institute of Dental Sciences, Delhi. Written consent was obtained for all treatments provided. No patient confidentiality was breached in the course of this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Piccininni PM, Fasel R. Sports dentistry and the Olympic Games. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2005;33:471–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Commonwealth Games Australia. Commonwealth Games Athletes Village. http://www.melbourne2006.com.au/Getting+Involved/About+the+Games/Games+Village/ [Accessed 13 March 2011]

- 3.Commonwealth Federation. 2010 Commonwealth Games. http://www.thecgf.com/games/intro.asp [Accessed 13 March 2011]

- 4.US Olympics Committee, Sports Medicine Council The Dental Family in the Olympic Movement. Olympian. 1982;9:14–15. [Google Scholar]