Abstract

Aims: Bisphenol A (BPA)-based dental composites have commonly been used to fill dental cavities or seal pits and fissures on teeth. However, epidemiological evidence with regard to the BPA exposure from dental composites among children has rarely been reported. This study investigated whether there is a relationship between the BPA concentration in urine and the presence of composite restorations and sealants among South Korean children. Methods: Oral examinations and urine sample analyses were conducted on a total of 495 children aged 8–9 years. We classified the participants into four groups by the number of resin composites and sealant surfaces (0, 1–5, 6–10 and 11+). Results: BPA concentrations in urine were higher in children with 11 or more surfaces restored with sealants and resin composites than in those with zero restored surfaces, although no difference was seen in the group with 1–10 surfaces. After adjusting for gender and age, the urinary BPA concentration in children with 11 or more resin composite surfaces was 2.67 μg/g creatinine, which was higher than the concentration found in those with no filling surfaces (P < 0.01). Conclusions: Having many dental composite filling surfaces on teeth may increase the urinary BPA concentration in children.

Key words: Bisphenol A, children, dental composites, sealant, urine

INTRODUCTION

Resin composites are being used as restorative materials with increasing frequency in dentistry because of the demand for aesthetic restorations and concerns about the adverse effects of mercury from amalgam1. Resin-based composite restorative materials consist of two major components: a resin matrix and a filler. Composites without fillers are known as sealants2. The resin matrix commonly contains monomers, such as 2,2-bis[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methacryloxy-propoxy)-phenyl]propane (Bis-GMA), urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) and/or triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA)3., 4.. After a curing process, unpolymerised monomers can be leached from the resin-based composites and may be absorbed systemically5.

Bis-GMA, the most commonly used matrix material for dental polymers6, is a methacrylate ester based on bisphenol A (BPA)7, which is known to disrupt endocrine function by mimicking oestrogen8, and has the potential to interfere with natural hormones in the human body9. As a result of the metabolism of BPA by androgens10, it has been reported that serum BPA levels are strongly associated with higher androgen concentrations. It has also been hypothesised that BPAs bind to oestrogen receptors in the pituitary gland, leading directly to the suppression of follicle-stimulating hormone secretion11. However, although many studies evaluating the effects of BPA exposure from various sources have been performed12., 13., there is little epidemiological evidence describing the amount of BPA leached from resin composites or sealants and its health effects in humans5., 8., 14..

As newborn children do not have fully developed metabolic mechanisms12, they are more susceptible than adults to possible adverse effects15 of the same levels of external BPA exposure. Therefore, it is important to determine the BPA levels derived from exposure to resin composites in children because of the age-dependent differences in metabolic clearance10. However, few studies have demonstrated the BPA concentrations in the body brought about by resin-based dental materials in children. For this reason, this study investigates the relationship between the number of sealant and/or composite filling surfaces and BPA concentration in urine among South Korean children.

METHODS

Study population

Five elementary schools were randomly selected from three metropolitan areas (Seoul, Daegu and Busan) of South Korea. A total of 495 children, who participated in the Children’s Health and Environmental Research (CHEER) study during 2007–2008, were chosen to be examined. All of the children were aged 8–9 years and were third-grade elementary school students. The study population and methods of the CHEER study have been described in detail elsewhere16. All participating parents and guardians provided written consent, and the study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dankook University College of Medicine and Ulsan University College of Medicine. The research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Oral examination

Two dentists trained in the examination protocol according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines17 conducted oral examinations to detect decayed, missing and filled surfaces of deciduous and permanent teeth, and to discern the filling materials in detail. Trained and calibrated dentists carried out an oral examination using a dental mirror and a WHO probe under appropriate artificial light. Cohen’s kappa coefficient for inter-examiner agreement was 0.89 for oral examination. The numbers of surfaces with resin, sealant and other dental substances, including restorative materials, as well as an amalgam on primary teeth and permanent teeth, were counted and classified into four groups: ‘none’, ‘1–5’, ‘6–10’ and ‘11 or more’.

Measurement of BPA concentration

Urine samples were taken and analysed to measure the concentrations of BPA18. The BPA concentrations used in this study were the creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentrations, which were calculated from the concentration of BPA in urine divided by the amount of creatinine in urine. To measure the concentration of BPA in urine, 5 mL of urine were drawn from each child and the samples were preserved at −80 °C before analysis; 1000 μL of urine sample from the participants, 30 μL of 2 m acetate buffer and 20 μL of enzyme were mixed thoroughly, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Then, 100 μL of 2 m HCl, 50 μL of a solution of the internal standard and 3 mL of ethyl acetate were added and incubated for 1 h; this was followed by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 5 min. An organic layer was evaporated under nitrogen and dissolved in 30 μL of 60% acetonitrile. Five microlitres of pre-treated sample were measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography-triple tandem mass detector (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, Agilent 6410) (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA)19. Potential contamination with BPA from other sources during collection, such as from plastic tubes, was minimal. The coefficient of variation for the BPA concentration was 4.7%.

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression models were built to analyse the association between the numbers of surfaces restored with different types of filling material (resin, sealant and resin composites, which were defined as the combination of the number of resin fillings and sealants in this study) and the creatinine-adjusted BPA concentration in urine. Regression models were adjusted by gender and age, as age and gender are two factors related to BPA concentrations in the body; however, these factors were not in the causal pathway between resin composite restoration and BPA concentration in urine12., 13., 20.. Data analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Distribution of filling materials

The percentages of boys and girls (n = 495) were 55.0% and 45.0%, respectively. The proportions of children dwelling in the Seoul, Daegu and Busan areas were 31.3%, 47.3% and 21.4%, respectively (data not shown).

The total average number of teeth filling materials in the study population was 10.07 ± 8.44. The average number of resin fillings was 1.23 ± 2.42. Children in Busan had more surfaces treated with resin fillings (2.36 ± 3.24) than those in other areas. The average number of surfaces with sealants was 2.33 ± 3.06, and children in Daegu had more abundant surfaces with sealants (2.72 ± 3.47) than those in other areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of filling materials in the study population by region

| Seoul (n = 155) | Daegu (n = 234) | Busan (n = 106) | Total (n = 495) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resin | 1.23 ± 2.19 | 0.71 ± 1.92 | 2.36 ± 3.24 | 1.23 ± 2.42 |

| Sealant | 2.39 ± 2.70 | 2.72 ± 3.47 | 1.38 ± 2.34 | 2.33 ± 3.06 |

| Amalgam | 1.80 ± 3.11 | 3.33 ± 4.05 | 2.28 ± 3.84 | 2.63 ± 3.79 |

| Other materials* | 4.26 ± 6.35 | 3.70 ± 6.51 | 3.68 ± 7.51 | 3.87 ± 6.68 |

| Total | 9.69 ± 8.25 | 10.48 ± 8.38 | 9.72 ± 8.87 | 10.07 ± 8.44 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Glass ionomer cement, gold, miracle, stainless steel crown, zinc oxide eugenol cement (ZOE) and zinc phosphate cement (ZPC).

BPA concentrations

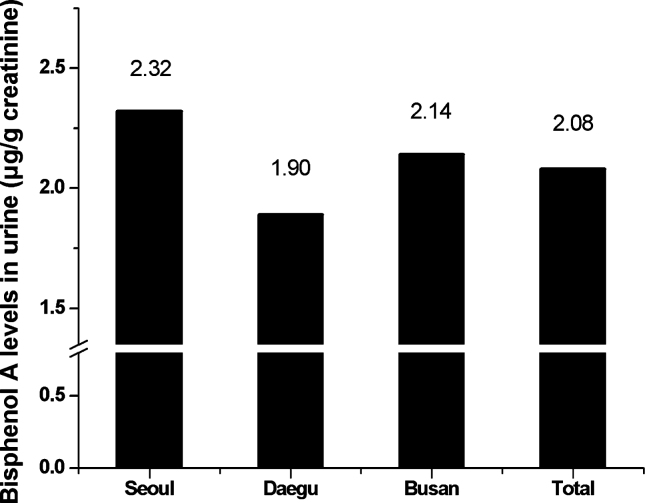

The average creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentration was 2.08 ± 3.81 μg/g creatinine; there was no statistically significant regional difference in the creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentrations according to area. Children in Seoul had the highest BPA concentration in their urine (2.32 ± 3.14 μg/g creatinine), whereas children in Daegu showed the lowest urinary BPA concentration (1.90 ± 4.35 μg/g creatinine) in the study population (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bisphenol A concentrations in urine according to area.

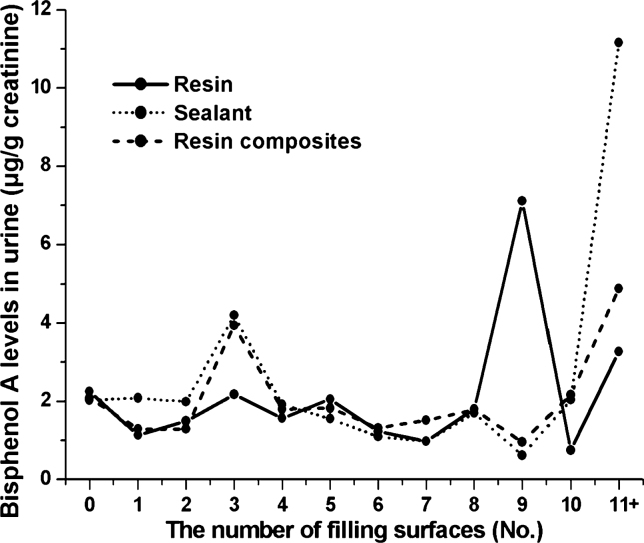

In Figure 2, the full, dotted and broken lines represent the urinary BPA concentrations of resin, sealant and resin composites, respectively. A change in urinary BPA concentration in children who were treated with sealants was not noticeable until they covered nine or ten surfaces. However, with the use of 11 or more sealants, the concentration of BPA in urine started to increase sharply. Nevertheless, it was hard to find a trend of an increase in urinary BPA concentration when teeth were restored with resin or resin composites, and BPA concentrations in urine were not significantly different at the point of more than 11 surfaces among the three categories of materials (P = 0.55; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bisphenol A concentrations in urine according to the number of surfaces restored with resin-based materials.

Associations between the number of filling surfaces and urinary BPA concentrations

In Table 2, regression model I shows the creatinine-adjusted crude urinary BPA concentration according to the classified group of surfaces with filling materials, and model II indicates the creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentration after adjusting for gender and age. BPA concentrations in urine in the group with 11 or more surfaces restored with sealants were 9.13 μg/g creatinine higher than in the reference group with no sealant in the oral cavity (P < 0.01). This trend was still significant after controlling for gender and age, and the concentration of urinary BPA was 9.10 μg/g creatinine in the same group (P < 0.01). In addition, BPA concentrations in urine in the group with 11 or more surfaces restored with resin composites were 2.67 μg/g creatinine higher than in the reference group (P < 0.01). However, no significant association was found between urinary BPA concentrations and the number of resin filling surfaces (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between the number of filling surfaces with resin-based restorative materials and the creatinine-adjusted BPA concentrations in urine

| Model I | Model II | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | P value | Beta coefficient | P value | |

| Surfaces with resin fillings | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1–5 | −0.65 | 0.11 | −0.65 | 0.12 |

| 6–10 | −0.43 | 0.54 | −0.34 | 0.63 |

| 11+ | 1.02 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 0.52 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boy | Reference | |||

| Girl | −0.32 | 0.43 | ||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.90 | ||

| Surfaces with sealants | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1–5 | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.20 | 0.62 |

| 6–10 | −0.63 | 0.17 | −0.59 | 0.21 |

| 11+ | 9.13 | <0.01 | 9.10 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boy | Reference | |||

| Girl | −2.29 | 0.46 | ||

| Age | 0.35 | 0.95 | ||

| Surfaces with resin composites* | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 1–5 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.97 |

| 6–10 | −0.49 | 0.25 | −0.45 | 0.31 |

| 11+ | 2.68 | <0.01 | 2.67 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boy | Reference | |||

| Girl | −0.29 | 0.47 | ||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.98 | ||

Unit: μg/g creatinine. Significant values are shown in bold (P < 0.01).

Resin composites included both resins and sealants.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the relationship between the number of surfaces filled with resin-based dental materials and the BPA concentrations in urine among a total of 495 South Korean children aged 8–9 years. Children who had 11 or more surfaces treated with sealants (9.1 μg/g creatinine) and resin composites (2.6 μg/g creatinine) showed significantly higher urinary BPA concentrations before and after controlling for gender and age (P < 0.01). However, no significant increases in BPA concentration were shown in the study population using resin fillings. This is the first large-scale study in South Korea investigating the effects of resin-based dental materials on children by measuring the creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentrations according to the number of surfaces treated with resin and sealant.

Other studies have demonstrated that BPA exposure results from the placement of composites or dental sealants2., 5., 8., 14.. A prospective cohort study examining exposure to BPA from dental sealants in 14 healthy military personnel, by measuring BPA concentrations in saliva and urine samples using isotope dilution mass spectrometry, found that salivary BPA concentrations increased dramatically after the placement of certain commercially available sealant brands. Furthermore, creatinine-adjusted BPA concentrations in urine remained elevated for at least 24 h after placement. As the authors eliminated a potentially significant amount of exposure to BPA by taking saliva samples immediately after sealant placement, the urinary measurements probably underestimated the total exposure to BPA5. The results showed that the creatinine-adjusted urinary BPA concentrations ranged from 0.17 to 45.4 mg/g creatinine, which was 1000 times higher than the average urinary BPA concentration (2.08 ± 3.81 μg/g) in this study. However, another study, which was designed to investigate the dose-dependent (8 and 32 mg) and time-dependent (1- and 3-h periods) release of BPA after the placement of sealant in 40 healthy adults, showed that BPA concentrations in saliva were 5.8–105.6 ppb. This suggests that BPA released from a dental sealant might not be absorbed, detected or metabolised14. Another study examining the salivary BPA concentrations in 21 patients showed that a maximum amount of 60.1 ng/mL of BPA in saliva remained after restoration with composite resins based on Bis-GMA or UDMA8. No agreement has been reached with regard to the systemic absorption of resin-based dental materials and the extent to which these materials have an adverse effect on health. In our study, the number of surfaces with sealants and resin composites correlated significantly with the BPA concentration, which might be connected with the results of another study, which demonstrated the effect of the different chemical structures of the composites and the ratio of filler to monomer on the leachable element21. Flowable composites containing less filler and more monomer than conventional materials were more cytotoxic in vitro22.

A number of studies have suggested that the BPA concentration in urine or blood is a biomarker of BPA which remains in the body as a result of the placement of resin-based dental materials5., 11., 13., 18., 23., 24., 25.. The oestrogenic effect of BPA has led to concerns with regard to its negative health effects. However, another study has recommended that a separate quantification of BPA and BPA glucuronide is necessary for use in risk assessments18. In humans, the administration of BPA in the mouth leads to rapid absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, and the conversion of BPA to BPA glucuronide in the liver. This is delivered to the bloodstream before reaching the kidneys, and is rapidly excreted by urine. BPA glucuronide is the major metabolite of BPA as a result of rapid glucuronidation, and therefore may be a suitable biomarker of human BPA exposure. Moreover, free BPA26, BPA dimethacrylate7 and other compounds27 have been suggested to be more strongly associated than BPA with potential oestrogenic effects.

The harmful effect of BPA as a hormone disrupter has been manifested. Several studies have dealt with BPA exposures resulting from the placement of composites or dental sealants. However, it is still controversial whether resins or sealants increase BPA concentrations and cause injuries in humans, especially in the South Korean population. Each step related to this issue should be uncovered. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aimed to explore the association between the number of resin composite filling surfaces and urinary BPA concentrations in South Korean children as a preliminary study, and to convey information on resin composites and other relative biomarkers, as well as BPA, from an extensive literature review.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, BPA is a material used in the manufacture of many types of product, including polycarbonate plastic food storage containers and epoxy resin used in the linings of canned food18., 23., 28.; therefore various environmental exposures make up potential sources of increased BPA in subjects’ bodies12. These potential confounders were not taken into account when adjusting for the factors affecting the BPA concentrations in urine, such as age and gender. Second, the background BPA concentrations were not measured at the beginning of the study. Although the reason remains unclear, a significant decline in urinary BPA concentrations was observed among Japanese schoolchildren followed for 5 years from the first to the sixth grade13. Although the BPA concentration in the natural state decreased significantly year by year, there was a relationship between the number of surfaces restored with sealants and resin and the BPA concentration in this analysis, suggesting that there is a positive association between resin composite dental fillings and BPA levels in the human body.

In spite of the limitations of this cross-sectional study caused by the low level of evidence, the authors believe that the results obtained can be used as a basis to carry out further investigations with advanced designs (to address the drawbacks of this study) to infer the causal relationship between the number of composite filling surfaces and urinary BPA concentration.

Acknowledgement

This study was performed with a grant for the CHEER study (a longitudinal cohort study on children’s environmental health) funded by the South Korean Ministry of the Environment.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors report any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouillaguet S, Shaw L, Gonzalez L, et al. Long-term cytotoxicity of resin-based dental restorative materials. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:7–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olea N, Pulgar R, Perez P, et al. Estrogenicity of resin-based composites and sealants used in dentistry. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:298–305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers JM, Sakaguchi RL. 12th edn. Mosby; New York, NY, USA: 2006. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polydorou O, Konig A, Hellwig E, et al. Long-term release of monomers from modern dental-composite materials. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joskow R, Barr DB, Barr JR, et al. Exposure to bisphenol A from bis-glycidyl dimethacrylate-based dental sealants. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:353–362. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noda M, Komatsu H, Sano H. HPLC analysis of dental resin composites components. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:374–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19991205)47:3<374::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarumi H, Imazato S, Narimatsu M, et al. Estrogenicity of fissure sealants and adhesive resins determined by reporter gene assay. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1838–1843. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790110401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki N, Okuda K, Kato T, et al. Salivary bisphenol-A levels detected by ELISA after restoration with composite resin. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:297–300. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-0627-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soderholm KJ, Mariotti A. BIS–GMA-based resins in dentistry: are they safe? J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:201–209. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi T, Tsutsumi O, Ikezuki Y, et al. Positive relationship between androgen and the endocrine disruptor, bisphenol A, in normal women and women with ovarian dysfunction. Endocr J. 2004;51:165–169. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.51.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanaoka T, Kawamura N, Hara K, et al. Urinary bisphenol A and plasma hormone concentrations in male workers exposed to bisphenol A diglycidyl ether and mixed organic solvents. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:625–628. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.9.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mielke H, Gundert-Remy U. Bisphenol A levels in blood depend on age and exposure. Toxicol Lett. 2009;190:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.06.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamano Y, Miyakawa S, Iizumi K, et al. Long-term study of urinary bisphenol A in elementary school children. Environ Health Prev Med. 2008;13:332–337. doi: 10.1007/s12199-008-0049-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung EY, Ewoldsen NO, St Germain HA, Jr, et al. Pharmacokinetics of bisphenol A released from a dental sealant. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:51–58. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamrin MA. Bisphenol A: a scientific evaluation. MedGenMed. 2004;6:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha M, Kwon HJ, Lim MH, et al. Low blood levels of lead and mercury and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity in children: a report of the children’s health and environment research (CHEER) Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . 4th edn. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1997. Oral Health Surveys; Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volkel W, Colnot T, Csanady GA, et al. Metabolism and kinetics of bisphenol A in humans at low doses following oral administration. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1281–1287. doi: 10.1021/tx025548t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dankook University, >The Korean Ministry of Environment . The South Korean Ministry of the Environment; Seoul, South Korea: 2009. A Longitudinal Cohort Study on Children’s Environmental Health (The 4th Year of Final Report) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi T, Tsutsumi O. Serum bisphenol A concentrations showed gender differences, possibly linked to androgen levels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:76–78. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Hiyasat AS, Darmani H, Milhem MM. Cytotoxicity evaluation of dental resin composites and their flowable derivatives. Clin Oral Invest. 2005;9:21–25. doi: 10.1007/s00784-004-0293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wataha JC, Lockwood PE, Bouillaguet S, et al. In vitro biological response to core and flowable dental restorative materials. Dent Mater. 2003;19:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brock JW, Yoshimura Y, Barr JR, et al. Measurement of bisphenol A levels in human urine. J Exp Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:323–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang M, Kim SY, Chang SS, et al. Urinary concentrations of bisphenol A in relation to biomarkers of sensitivity and effect and endocrine-related health effects. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2006;47:571–578. doi: 10.1002/em.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye X, Pierik FH, Angerer J, et al. Levels of metabolites of organophosphate pesticides, phthalates, and bisphenol A in pooled urine specimens from pregnant women participating in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009;212:481–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkel W, Kiranoglu M, Fromme H. Determination of free and total bisphenol A in human urine to assess daily uptake as a basis for a valid risk assessment. Toxicol Lett. 2008;179:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada H, Tarumi H, Imazato S, et al. In vitro estrogenicity of resin composites. J Dent Res. 2004;83:222–226. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Is there a risk of harm of toxicity in the placement of pit and fissure sealant materials? A systemic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]