Abstract

Background: In recent years, disasters that overwhelm the capacity of humans have been frequent. However, international cooperation has been swift as a result of advances in transportation, enabling the more prompt administration of First Aid. Methods: We have had two opportunities to observe outcomes in oral hygiene immediately after and 10 months after two different major disasters. Results: The types of food provided to survivors altered their sense of taste and resulted in the occurrence of dental caries several months after an earthquake. In addition, it is difficult to practise good oral hygiene in the aftermath of a disaster. Conclusions: We observed the occurrence of previously undocumented problems related to dental issues, such as changes in children’s sense of taste caused by unfamiliar types of food provided in relief shelters. Dentists and dental hygienists who are involved in the relief of survivors in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster should focus on maintaining good oral health in order to prevent the occurrence of dental caries.

Key words: Disaster, oral hygiene, dental caries, pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Many manuscripts have described the activities of medical teams in the immediate aftermath of natural disasters such as earthquakes, and the importance of oral health care programmes in this context1., 2., 3.. Dentists may be involved in three stages of response after such an event: the First Aid stage; the settlement stage, and the reconstruction stage. Major tasks during the First Aid stage include the treatment of facial injuries. In the settlement stage, dentists and dental hygienists are required to provide oral health care to survivors living in temporary shelters. In the reconstruction stage there is great demand for dental treatment in affected areas. However, few studies have reported on follow-up investigations into oral health conditions after disasters. We have had a rare opportunity to be involved as dentists in major earthquake relief efforts in Haiti and Japan. In this article, we report outcomes in oral health in Haiti 10 months after the 2010 earthquake there and in Japan immediately after the 2011 earthquake there.

An earthquake with a magnitude of 7.2 struck Haiti on 12 January 2010. Over 200,000 people are thought to have died and many survivors lost their homes. The Great East Japan Earthquake occurred on 11 March 2011, with a magnitude of 9.0. Although the area affected by the quake was widespread, the damage was very limited. The tsunami caused by the earthquake was far more destructive than the actual quake. The Japanese National Police Agency has confirmed 15,754 deaths and 4,460 people missing.

This research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. We obtained verbal consent from all participants involved in the study. The study has not been independently reviewed and approved by a research ethics board.

HAITI

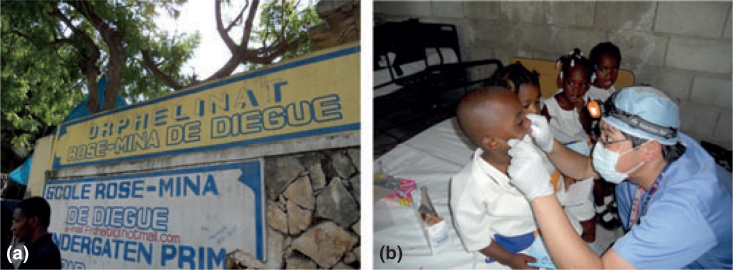

We had the opportunity to visit Haiti with a medical team during 16–23 0ctober 2010. We carried out dental check-ups and preventive care in two orphanages (Figure 1), of which one was located in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, and the other in the city’s suburbs.

Figure 1.

(a) The orphanage in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. (b) A dental check-up is conducted in the orphanage in a suburb of Port-au-Prince.

Sugar consumption in Haiti was the lowest in the Americas region in 2005, despite having increased since 19994. Furthermore, Haiti has a high level of malnutrition, which is associated with the delayed eruption of the primary teeth5. As a result, prior to the earthquake, Haiti had the lowest prevalence of dental caries in the Americas4. However, of the 120 children we examined, we found 32 children (26.7%) to be caries-free and 88 (73.3%) to have dental caries, thereby establishing an increase in the prevalence of dental caries. One possible reason for this increase is that international medical teams distribute sweets to surviving children. During our stay in Port-au-Prince, we often witnessed children asking foreigners for chocolate and candy. We used the data obtained in our observations to compare findings in two different orphanages, of which one was urban and the other suburban. Each child was assigned to one of six categories of caries severity using a scale of 0–5, on which 0 = caries-free and 5 = most severe caries6 (Table 1). The proportion of children with severe dental caries was higher in the urban than the suburban orphanage. A total of 25.0% of children in the urban orphanage had severe dental caries (scores of 4 and 5) (Table 2), whereas only 7.8% of children in the suburban orphanage did so. Furthermore, 37.5% of children in the suburban orphanage were caries-free. As the number of survivors was far greater in urban areas, international medical teams had been more active there. This suggests an increase in sugar consumption, which is a major aetiological factor in dental caries in urban areas7., 8.. In developing countries, sugar consumption is low and thus the occurrence of dental caries is also low. As sugar consumption increases in those countries, so does the prevalence of dental caries9.

Table 1.

Caries severity measured on a scale of 0–5

| Severity score | Definition according to dental surfaces involved |

|---|---|

| 5 | Proximal surfaces of mandibular anterior teeth (excluding distal surfaces of cuspids) |

| 4 | Labial surfaces of maxillary and mandibular incisors and cuspids (excluding those of maxillary cuspids) |

| 3 | Proximal surfaces of maxillary anterior teeth (excluding distal surfaces of cuspids) |

| 2 | Proximal surfaces of molars and premolars (including distal surfaces of cuspids) |

| 1 | Pit and fissure surfaces of posterior teeth and labial surfaces of maxillary cuspids |

| 0 | None of the above |

Table 2.

Post-earthquake prevalences of dental caries in children in urban and suburban orphanages in Haiti

| Children scoring 0–5, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Urban (n = 56) | 8 (14.3%) | 6 (10.7%) | 13 (23.2%) | 15 (26.8%) | 10 (17.9%) | 4 (7.1%) |

| Suburban (n = 64) | 24 (37.5%) | 20 (31.3%) | 11 (17.2%) | 4 (6.3%) | 5 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total (n = 120) | 32 (26.7%) | 26 (21.7%) | 24 (20.0%) | 19 (15.8%) | 15 (12.5%) | 4 (3.3%) |

JAPAN

In the Great East Japan Earthquake, a tsunami occurred after the quake had struck the east coast of Tohoku, which is 180 km long. The local population had only 30 minutes to evacuate to shelters. Over 125,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, with the result that survivors in this area lost almost all their property (Figure 2a). Road damage and flooding, which lasted for 3 days, made it very difficult for rescue teams to reach the affected area (Figure 2b). Hence, survivors in some shelters had access to little food during this period. The food provided in these shelters consisted of items with a long shelf life, such as candy and chocolate, and was high in calories. Further, as in Haiti, children who survived the Japanese earthquake were frequently given sweets by medical personnel.

Figure 2.

(a, b) Effects of the tsunami that followed the 2011 earthquake in Ishinomaki, Japan. (c) A dentist applies fluoride gel to the teeth of a child in a shelter. (d) Dental hygienists teach elementary school students how to brush their teeth. (e) Dentists and dental hygienists visited elderly survivors in shelters to assess their oral health. (f) Dentures of elderly survivors were found to be covered with plaque and food residue.

In addition, tap water at many shelters was limited and survivors were convinced that they were unable to brush their teeth without tap water. Older people hesitated to wash dentures because of the shortage of tap water and the inconvenient locations of washrooms. When we visited shelters to promote oral hygiene 2 weeks after the quake, we found many dentures displayed dental plaque and food residue (Figure 2f). Furthermore, it took about 2 weeks to distribute toothbrushes and toothpaste to shelters. Although we continued to stress the importance of oral hygiene, we found that oral hygiene practices were discarded because other issues were seen as more pressing.

Finally, the food provided in the shelters tasted differently to the food survivors had eaten in their homes. It appeared that children wanted to eat only sweets and rejected balanced meals. However, it was difficult for parents to oversee what their children ate in these conditions.

Actions taken for children

We began to provide oral health services to survivors in shelters 1 week after the quake. First, we provided oral care products such as toothbrushes, toothpaste, dental rinses and denture cleaners. We also applied fluoride gel to the teeth of children living in shelters (Figure 2c) and stressed the importance of oral hygiene to their guardians.

Schools in the affected areas restarted classes 2 months after the tsunami. At June 2011, mean scores on the decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index in 12-year-old children in the affected area were higher than in children across Japan (2.10 vs. 1.29). We visited elementary schools to educate children about the prevention of dental caries (Figure 2d). For instance, dentists and dental hygienists confirmed the importance of brushing with fluoridated toothpaste and taught children to use fluoridated mouth rinses because tap water in Japan is not fluoridated.

Actions taken for elderly people

Subsequently to the earthquake, oral hygiene in older people was alarmingly poor as dentures remained uncleaned. Dental plaque and tongue-coatings are known to function as reservoirs for pneumonia infection in elderly individuals10., 11.. Oral hygiene care reduces the risk for mortality from pneumonia12., 13.. Thus, dental hygienists visited elderly survivors in shelters to clean their mouths and dentures in order to prevent pneumonia (Figure 2e).

Many dentists and dental hygienists from all over Japan visited the affected area as part of the national relief effort. In the First Aid stage, their main tasks included the provision of oral care to the elderly population in shelters because they were less able to properly treat other patients as a result of shortages of electricity, water and dental supplies and instruments. Equipment for oral care, such as toothbrushes, toothpastes, sponge brushes, dental rinses and denture cleaners, should be stockpiled for easy access in future disasters.

CONCLUSIONS

The tasks of dentists in the immediate aftermath of a disaster are generally considered to include the reconstruction of bone fractures and forensic medicine investigations2., 14.. However, our experiences in these two major earthquakes lead us to conclude that the promotion and maintenance of oral hygiene should be a priority in the First Aid stage of response, especially in view of the increased sugar consumption of children and the difficulties in brushing teeth caused by lack of water, toothbrushes and toothpaste. Furthermore, the sense of taste in children seems to change quickly as a result of their consumption of the type of food provided in shelters. Thus, in the future, disaster relief teams attending disaster-stricken areas should include dentists and dental hygienists in order to maintain better oral hygiene and thereby to limit the occurrence of pneumonia and dental caries.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Eugene Sekiguchi (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA), for his critical reading of this manuscript, and the Sai Organisation for providing accommodation in Haiti.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang L, Wei JH, He LS, et al. Dentists’ role in treating facial injuries sustained in the 2008 earthquake in China: how dental professionals can contribute to emergency response. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:543–549. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai J, Zhao Y, Li G. Wenchuan earthquake: response of Chinese dental professionals. Br Dent J. 2009;206:273–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz CH, Koenig KL, Noji EK. A medical disaster response to reduce immediate mortality after an earthquake. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:438–444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO Oral Health Country/Area Profile Programme. Available from: http://www.mah.se/CAPP/Country-Oral-Health-Profiles/According-to-WHO-Regions/. Accessed 29 August 2011

- 5.Psoter WJ, Reid BC, Katz RV. Malnutrition and dental caries: a review of the literature. Caries Res. 2005;39:441–447. doi: 10.1159/000088178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulsen S, Horowitz HS. An evaluation of a hierarchical method of describing the pattern of dental caries attack. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1974;2:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1974.tb01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mobley C, Marshall TA, Milgrom P, et al. The contribution of dietary factors to dental caries and disparities in caries. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelstein BL. The dental caries pandemic and disparities problem. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl 1):2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zero DT. Sugars – the arch criminal? Caries Res. 2004;38:277–285. doi: 10.1159/000077767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe S, Ishihara K, Adachi M, et al. Tongue-coating as risk indicator for aspiration pneumonia in edentate elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Colonisation of dental plaques: a reservoir of respiratory pathogens for hospital-acquired pneumonia in institutionalised elders. Chest. 2004;126:1575–1582. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassim CW, Gibson G, Ward T, et al. Modification of the risk of mortality from pneumonia with oral hygiene care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1601–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quagliarello V, Ginter S, Han L, et al. Modifiable risk factors for nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1–6. doi: 10.1086/426023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colvard MD, Lampiris LN, Cordell GA, et al. The dental emergency responder: expanding the scope of dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:468–473. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]