Abstract

Objectives: To assess the ability of 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride dentifrice to maintain gingival health compared to a sodium fluoride control dentifrice. Design: Following a baseline examination, subjects went through a regimen to bring them to a high level of gingival health. This included a professional prophylaxis supported by oral hygiene instruction prior to commencing study treatment. Subjects brushed twice daily for 12 weeks with either the test or control dentifrice. Examinations for gingival inflammation (MGI), bleeding and plaque were performed after 6 and 12 weeks. Results: 224 subjects were included in the efficacy analysis. Relative to the sodium fluoride/ silica control dentifrice group the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice exhibited statistically significant reductions (p < 0.0001) in MGI, bleeding and plaque of 12.3%, 18.5% and 13.2% respectively after six weeks and 38.1%, 37.8% and 24.2% after 12 weeks. Conclusion: The results of the present clinical study demonstrate that the use of the 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride dentifrice over a 12 week period provides a statistically significant benefit in maintaining gingival health compared to a sodium fluoride control dentifrice.

Key words: Dentifrice, gingival health, zinc chloride

INTRODUCTION

Gingivitis is a commonly occurring gingival disease characterised by accumulation of bacterial plaque leading to reversible inflammation along the gingival margin. If left untreated, gingivitis may lead to the more serious irreversible disease periodontitis. It is recognised that the presence of dental plaque is a precursor to gingivitis and that gingivitis can be significantly reversed through adequate control of dental plaque1. It is widely accepted that keeping the teeth free of dental plaque by a thorough oral hygiene regimen is key to maintaining oral health2., 3., 4.. However, removing sufficient dental plaque mechanically simply by brushing, particularly from those sites in the mouth which are less accessible with a toothbrush is technically difficult and time consuming. The introduction of antimicrobial ingredients in oral care products to help control dental plaque is now widespread5., 6.. Such agents including triclosan, zinc salts and stannous are discussed in reviews by Brading and Marsh7, Eley8 and further by Pizzey9.

The most effective means of controlling dental plaque is through professional dental prophylaxis. This has been shown to be highly effective in reducing gingivitis10. Sturzenberger11 reported that the greatest effect of a dental prophylaxis on gingivitis can be observed 7 to 10 days after treatment, following this gingivitis increased with the recurrence of dental plaque. In healthy patients, the typical time period between dental cleanings is six months. It is highly desirable to have products that will help to maintain the healthy state obtained from professional dental cleanings between these visits. Typically, evaluation of efficacy of over the counter anti-gingivitis toothpastes is carried out in studies where subjects undergo a dental prophylaxis at baseline and then immediately start to use the study treatment12., 13., 14.. The effect of the dental prophylaxis itself during these studies is unknown as comparisons are made relative to baseline (pre-prophylaxis) gingivitis scores without separately evaluating the effect of the prophylaxis.

In order to truly assess the ability of a dentifrice to maintain the level of gingival health obtained from dental prophylaxis, it is important to utilise a clinical study design where subjects are first brought to their optimum gingival health prior to commencing study treatment. Other researchers have utilised clinical study designs which employed a ‘pre-experimental phase’ where subjects were brought to an improved level of gingival health prior to study treatment. Svatun15., 16. demonstrated that a dentifrice containing zinc citrate was able to maintain gingival health to a greater extent than a control dentifrice in student nurses over a one year period. The study design employed a dental prophylaxis at baseline followed by a 4-week pre-experimental phase of oral hygiene instruction to bring subjects to a pre-determined level of gingival health based on number of bleeding sites. Gordon17 compared Listerine antiseptic mouthrinse to an essential oil free mouthrinse vehicle control and water in a nine month maintenance of gingival health clinical study. The study design employed a four week pre-experimental phase where subjects underwent multiple dental prophylaxes to optimise their gingival health prior to treatment. The findings of this study indicated that Listerine antiseptic mouthrinse significantly reduced the development of plaque at 1, 3, 6 and 9 months and the development of gingivitis at nine months as compared to its vehicle control or water rinses. Gordon did not observe a significant difference between the test and control mouthrinses in gingivitis until the nine month visit despite an earlier study by Lamster13 which had shown a significant effect on gingivitis after 1, 3 and 6 months for the same product. Gordon hypothesised that this was due the low levels of gingivitis from the pre-experimental phase in their study compared to the study of Lamster. Despite the slightly different approaches to obtaining improved gingival health through a pre-experimental phase, both Svatun and Gordon observed a significant improvement in their studies compared to baseline prior to commencing treatment.

The objectives of this clinical study were to assess the ability of a dentifrice containing 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol and 0.6%w.w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) to maintain gingival health following a 14 day pre-experimental phase of dental prophylaxis and oral hygiene instruction prior to study treatment compared to a regular sodium fluoride/ silica based dentifrice. In addition the ability of the test dentifrice to control dental plaque was also assessed. The unique combination of o-cymen-5-ol and zinc chloride has resulted in a spectrum of antimicrobial activity greater than for each of the ingredients alone9. The product was used twice daily and assessments of gingival inflammation, bleeding and plaque were conducted after six and 12 weeks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a single centre, examiner blind, two arm, parallel group, randomised and stratified clinical study in healthy adult volunteers conducted at Global Health Research Group, New Delhi, India to assess the ability of a dentifrice containing 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol and 0.6%w/w zinc chloride to maintain gingival health over a 12 week period compared to a control sodium fluoride/ silica dentifrice. The study protocol and consent form were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Global Health Research Group. After providing written informed consent, 325 healthy adult subjects between the ages of 18–65 years were screened in April 2010, with 239 subjects randomised to study treatment. The study was completed in August 2010. Subjects were enrolled into the study if they had:

-

•

Good oral health with at least 20 natural teeth (excluding third molars) and mild to moderate gingivitis at baseline (mean whole mouth Modified Gingival Index (MGI) score 1.50–2.50). Additionally they would have to demonstrate a reduction in MGI and a reduction or no change in bleeding during the pre-experimental phase.

Subjects were excluded from the study if they:

-

•

Were pregnant or breast feeding.

-

•

Were smokers.

-

•

Had dental conditions requiring immediate treatment, sensitivity to oral care products, active caries, severe periodontitis or gingivitis; partial dentures, orthodontic appliances or fixed retainers or restorations in a poor state of repair.

Subjects were also screened for the use of any systemic medication which would have an effect on gingival conditions (e.g. antibiotics, calcium channel blockers, ibuprofen or aspirin therapy) within 14 days of any gingivitis assessment.

The study was conducted in two phases: a two week pre-experimental phase and a 12 week experimental period with a total duration of 14 weeks. Following an initial screening visit, at the start of the pre-experimental phase (Pre-Prophy Baseline visit) subjects underwent oral soft tissue (OST), gingival inflammation using the Modified Gingival Index (MGI)18, bleeding using the Bleeding Index (BI)19 and plaque using the six site Turesky Modification of the Quigley Hein Index (TPI)20 examinations (having abstained from brushing for a 12 hour period prior to the visit). To obtain optimum gingival health, subjects received a thorough professional dental prophylaxis. Afterwards, subjects received thorough professional instruction in oral hygiene which included the use of a medium bristled manual toothbrush (Aquafresh® Clean Control®) (Aquafresh and Clean Control are registered trademarks of GlaxoSmithKline group of companies) with a sodium fluoride/ silica toothpaste (Colgate® Herbal, Indian marketed product) (Colgate Herbal is a registered trademark of Colgate-Palmolive). They were instructed to use these products brushing twice daily at home for the next 14 days. Written instructions, a timer and a diary card to record brushing occasions were provided. Subjects returned to the site after seven days (two hours since their last brushing) for an additional visit at which they received an OST assessment followed by brushing their teeth under supervision followed by plaque disclosure. A qualified dental professional highlighted areas missed during brushing and reviewed the oral hygiene instructions, residual plaque was then removed by professional dental polishing.

Subjects returned to site 14 days after the Pre-Prophy Baseline visit for the randomisation visit (after abstaining from brushing for 12 hours) and underwent OST, MGI, BI and TPI assessments. Only subjects who demonstrated a decrease in MGI and a decrease or no change in bleeding over the two week period since the Pre-Prophy Baseline visit were entered into the experimental phase of the study. Subjects were stratified according to their MGI score from the Pre-Prophy Baseline Visit and randomly assigned either the dentifrice containing 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol and 0.6%w/w zinc chloride in a 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride/ silica base or a 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride/ silica base dentifrice. Subjects underwent a professional dental polishing with their assigned treatment and entered into the experimental phase. Subjects were instructed to brush twice daily (Aquafresh Clean Control flat trim toothbrush) at home for one timed minute with their assigned treatment using a strip of toothpaste that covered the head of the study toothbrush. Treatment compliance was assessed from diaries that the subjects completed each time they brushed at home throughout the study.

At 6 and 12 weeks after randomisation subjects returned for appointments with overnight plaque and underwent OST, MGI, BI and TPI assessments.

Randomisation and blinding procedure

The randomisation schedule was generated using a computerised randomisation generator and provided to the site by the Biostatistics Department of the sponsor. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups according to the method of permuted blocks using a fixed block size of four. Subjects were stratified according to their Pre-Prophy Baseline MGI score into one of two strata: Low MGI (1.50–<2.00) and High MGI (≥2.00). Randomisation numbers were assigned within each strata chronologically as subjects were randomised to treatment. Study staff dispensing the treatment were blinded to the treatment identities. The examiners and the study statistician, data management staff and other employees of the Sponsor who may influence study outcomes were blinded to the treatment allocation of subjects. The study treatments were both white toothpastes provided in plain white tubes with study label detailing the treatment code and instructions for use to ensure the subject was unaware of which treatment they received. Subjects were re-supplied with study treatment and a new toothbrush at the six week visit.

Modified gingival index

The MGI18 is a non-invasive evaluation of early visual changes in severity and extent of gingivitis. The MGI was assessed by a single examiner grading facial and lingual surfaces at two sites on each tooth (papillae and margin) using standard dental illumination under office conditions. The MGI scoring system was as follows:

0 = absence of inflammation

1 = mild inflammation; slight change in colour, little change in colour; little change in texture of any portion of the marginal or papillary gingival unit

2 = mild inflammation; criteria as above but involving the entire marginal or papillar gingival unit

3 = moderate inflammation; glazing, redness, oedema, and/or hypertrophy of the marginal or papillary gingival unit

4 = severe inflammation; marked redness, oedema and/or hypertrophy of the marginal or papillary gingival unit, spontaneous bleeding, congestion, or ulceration.

Bleeding Index

The bleeding index (modified Index of Saxton19) was performed by a single examiner using a colour coded periodontal probe. The probe was engaged approximately 1 millimetre (mm) into the gingival crevice. A moderate pressure was used whilst sweeping along the sulcular epithelium gingiva.

The BI scoring system was as follows:

0 = no bleeding after 30 seconds

1 = bleeding upon probing after 30 seconds

2 = immediate bleeding observed

Dental plaque assessment

A single dental examiner used a six-site modification of the Turesky Modification of the Quigley Hein Index20 to assess plaque on all gradable teeth. Only natural teeth (excluding third molars) were assessed.

The plaque was disclosed using 5 ml of a dye solution (Red Cote®) (Red Cote is a registered trademark of Butler) for 10 seconds followed by rinsing with 10 ml of water for 10 seconds. Each tooth was divided into six areas: mesiofacial, facial, distofacial, mesiolingual, lingual and distolingual surfaces.

Disclosed plaque was scored as follows:

Score Description

-

0

No plaque

-

1

Slight flecks of plaque at the cervical margin of the tooth

-

2

A thin continuous band of plaque (1 mm or smaller) at the cervical margin of the tooth

-

3

A band of plaque wider than 1 mm but covering less than 1/3 of the area

-

4

Plaque covering at least 1/3 but less than 2/3 of the area

-

5

Plaque covering 2/3 or more of the crown of the tooth.

Statistical methods

To detect a between-treatment difference in MGI of 0.09 (SD = 0.19), with a two-sided 5% significance level and a power of 90%, a sample size of 90 subjects per group was required. To allow for withdrawals from the study, approximately 115 subjects per group were randomised.

The MGI and BI were calculated taking the average over all tooth sites for a subject. Teeth which were missing or not gradable were excluded from all calculations.

The MGI and BI were compared between treatments using a mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis. The statistical model included factors for treatment group, time, and treatment:time interaction, and the pre-prophy baseline and randomisation baseline levels of MGI and BI as covariates, and each of the baseline:time interaction terms. The gingival strata level was not included as the actual baseline level was included as a covariate. BI was transformed (square root transformation) prior to analysis, in order to ensure Normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions were met.

In all repeated measures analyses, subject was the unit of analysis and an unstructured covariance matrix was specified. The statistical analysis was based on observed cases. However, using the MMRM methodology, those subjects with missing data at the week 12 assessment were included in the statistical analysis.

The Turesky modification of the Quigley Hein Index (overall) was calculated taking the average over all tooth sites for a subject. The interproximal scores were calculated in the same way as for the overall scores but just based on the mesiofacial, distofacial, mesiolingual and distolingual surfaces. Teeth which were missing or not gradable were excluded from all calculations.

The whole tooth plaque and interproximal plaque were compared between treatments using a MMRM analysis. The statistical model included treatment group, time, strata level of gingival index and treatment:time interaction as factors, and the pre-prophylaxis baseline and randomisation baseline whole mouth plaque score as covariates, and each of the baseline:time interaction terms.

The margin and papillae scores for MGI and BI were based on the mean scores just from the gingival margin areas (facial and lingual) and the papillae areas (facial and lingual). The MGI and BI (for margin and papillae regions separately) were compared between treatments using a MMRM analysis. The statistical model included factors for treatment group, time, and treatment:time interaction, and the pre-prophy baseline and randomisation baseline levels of MGI and BI (whole mouth scores) as covariates, and each of the baseline:time interaction terms.

RESULTS

Three hundred and twenty five adult subjects were screened, with 239 subjects randomised to study treatment. A total of 224 subjects were included in the efficacy analysis which was based on the Intent to Treat (ITT) population. Thirty four of the randomised subjects did not complete the study, one was due to an adverse event and the other 33 were lost to follow up.

Demographics

The baseline demographics for the study population are summarised in Table 1 and show that the two treatment groups were balanced with respect to age, sex and Pre-Prophy Baseline MGI scores of the subjects.

Table 1.

Demographics of intent to treat study population

| Treatment | Number of Subjects | Age (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Overall | MGI Score* (1.5–<2.00) | MGI Score* (≥2.00) | Mean | Range | |

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%zinc chloride (ZnCl22) | 62 | 50 | 112 | 67 | 45 | 25.7 | 18–45 |

| 0.204% Sodium fluoride | 51 | 61 | 112 | 67 | 45 | 26.8 | 18–54 |

MGI score at Pre-Prophy Baseline visit.

Pre-experimental phase

The purpose of the pre-experimental phase was to bring subjects to their optimum gingival health prior to commencing study treatment. MGI, BI and TPI all showed significant reductions between the pre-prophylaxis visit and the randomisation visit (Table 2). There was a 76.8% reduction in MGI, a reduction of 69.4% in BI and a 28.4% reduction in TPI. All these reductions were statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Summary of changes during pre-experimental phase (Pre-Prophy Baseline to Randomisation Visits)

| Index | Mean Score (±SD) | Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Prophy Baseline (N = 224) | Randomisation (N = 224) | Mean Difference (%) | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Modified Gingival Index | 1.90 ± 0.203 | 0.44 ± 0.251 | −1.46 (76.8%) | −1.49, −1.42 | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding Index | 0.64 ± 0.238 | 0.20 ± 0.105 | −0.43 (69.4%) | −0.36, −0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Plaque Index | 3.34 ± 0.308 | 2.39 ± 0.441 | −0.95 (28.4%) | −1.00, −0.89 | <0.0001 |

Comparison based on model-adjusted means.

Experimental phase

Comparison of mean modified gingival index scores

The pre-prophylaxis baseline MGI scores for the 224 subjects included in the efficacy analysis are presented in Table 3. The control dentifrice group had a mean MGI score of 1.91 while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a score of 1.89. The mean MGI scores for the two dentifrice groups after six and 12 weeks dentifrice use are also presented in Table 2. The control dentifrice group had a mean MGI score of 1.75 and 1.56 (6 and 12 weeks of product use respectively), while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a mean MGI score of 1.52 and 0.96 (6 and 12 weeks of product use respectively). These MGI scores were 12.3% and 38.1% lower compared to the control dentifrice and constituted statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Summary of Modified Gingival Index over time

| Time point | Mean Modified Gingival Index (±SD) | Between Treatment Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | Mean Difference (%) | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | 1.89 ± 0.211 | 1.91 ± 0.195 | |||

| Randomisation | 0.45 ± 0.258 | 0.44 ± 0.246 | |||

| Week 6 | 1.52 ± 0.207 | 1.75 ± 0.192 | −0.21 (−12.3%) | −0.24, −0.19 | <0.0001 |

| Week 12** | 0.96 ± 0.267 | 1.56 ± 0.192 | −0.59 (−38.1%) | −0.64, −0.55 | <0.0001 |

0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice vs 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride dentifrice, a negative difference favours the experimental dentifrice. Comparison based on model-adjusted means.

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

The MGI scores were separately analysed to evaluate the margin and papillae, this is presented in Table 4. The results closely mirrored the overall mean scores indicating that the severity of the inflammation was similar in both the margin and papillae sites.

Table 4.

Summary of Modified Gingival Index Margin and Papillae scores

| Timepoint | Margin or papillae | Mean Modified Gingival Index (±SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | ||

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | Margin | 1.88 ± 0.209 | 1.90 ± 0.193 |

| Papillae | 1.89 ± 0.213 | 1.92 ± 0.199 | |

| Randomisation | Margin | 0.47 ± 0.252 | 0.45 ± 0.236 |

| Papillae | 0.44 ± 0.266 | 0.42 ± 0.257 | |

| Week 6* | Margin | 1.51 ± 0.206 | 1.75 ± 0.190 |

| Papillae | 1.52 ± 0.213 | 1.76 ± 0.198 | |

| Week 12*,** | Margin | 0.98 ± 0.262 | 1.57 ± 0.188 |

| Papillae | 0.93 ± 0.280 | 1.55 ± 0.200 | |

Between treatment differences based on model-adjusted means were statistically significant (P < 0.0001) for week 6 and week 12 in favour of 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice for margin and papillae.

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

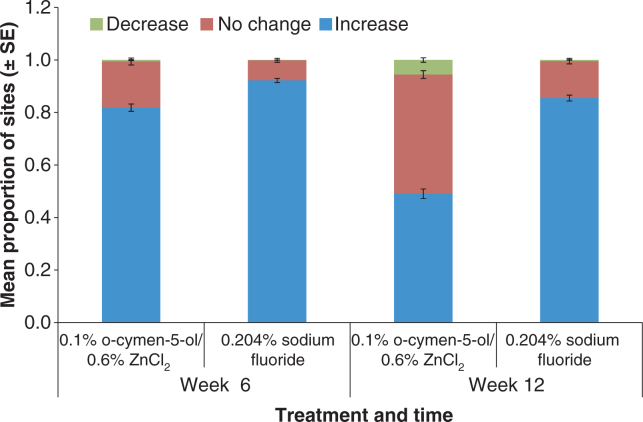

The MGI scores were evaluated to determine the number of individual sites that increased, decreased or showed no change in MGI from the randomisation visit at weeks 6 and 12. This is illustrated in Figure 1 as the relative proportion of sites showing increase, decrease or no change in MGI for each treatment.

Figure 1.

Proportion of tooth sites that showed increase, no change and decrease in MGI after 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Comparison of bleeding index scores

The pre-prophylaxis baseline BI scores for the 224 subjects included in the efficacy analysis are presented in Table 5. The control dentifrice group had a mean BI score of 0.64 while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a score of 0.63. The mean BI scores for the two dentifrice groups after 6 and 12 weeks dentifrice use are also presented in Table 5. The control dentifrice group had a mean BI score of 0.35 and 0.20 (6 and 12 weeks respectively), while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a mean BI score of 0.29 and 0.13 (6 and 12 weeks respectively). These BI scores were 18.5% and 37.8% lower compared to the control dentifrice and constituted statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001).

Table 5.

Summary of Bleeding Index over time

| Time point | Mean Bleeding Index (±SD) | Between Treatment Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | Mean Difference (%) | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | 0.63 ± 0.250 | 0.64 ± 0.227 | |||

| Randomisation | 0.20 ± 0.110 | 0.20 ± 0.101 | |||

| Week 6 | 0.29 ± 0.144 | 0.35 ± 0.141 | −0.06 (−18.5%) | (−0.08, −0.04) | <0.0001 |

| Week 12** | 0.13 ± 0.075 | 0.20 ± 0.100 | −0.09 (−37.8%) | (−0.11, −0.07) | <0.0001 |

0.1% w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice vs 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride dentifrice, a negative difference favours the experimental dentifrice. Comparison based on model-adjusted means. Difference based on transformed values (square root transformation).

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

The BI scores were separately analysed to evaluate the margin and papillae, this is presented in Table 6. The BI scores were lower at the papillae sites than the margin sites. The between treatment differences were statistically significant in both cases.

Table 6.

Summary of Bleeding Index Margin and Papillae scores

| Time point | Margin or papillae | Mean Modified Gingival Index (±SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | ||

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | Margin | 0.71 ± 0.265 | 0.71 ± 0.252 |

| Papillae | 0.55 ± 0.274 | 0.57 ± 0.253 | |

| Randomisation | Margin | 0.25 ± 0.114 | 0.25 ± 0.108 |

| Papillae | 0.16 ± 0.115 | 0.15 ± 0.106 | |

| Week 6* | Margin | 0.34 ± 0.156 | 0.40 ± 0.156 |

| Papillae | 0.23 ± 0.142 | 0.30 ± 0.147 | |

| Week 12*,** | Margin | 0.17 ± 0.083 | 0.24 ± 0.104 |

| Papillae | 0.08 ± 0.073 | 0.16 ± 0.107 | |

Between treatment differences based on model-adjusted means were statistically significant (P < 0.0001) for week 6 and week 12 in favour of 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice for margin and papillae.

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

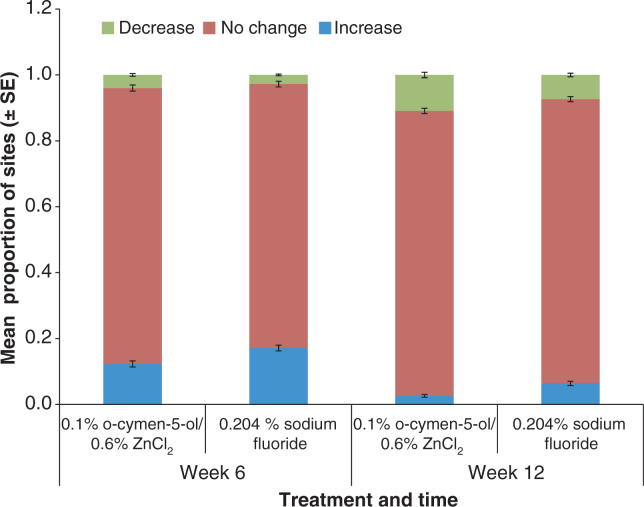

The BI scores were evaluated to determine the number of individual sites that increased, decreased or showed no change in BI from the randomisation visit at weeks 6 and 12. This is illustrated in Figure 2 as the relative proportion of sites showing increase, decrease or no change in BI for each treatment.

Figure 2.

Proportion of tooth sites that showed increase, no change and decrease in Bleeding Index after 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Comparison of plaque index scores

The pre-prophy baseline TPI scores for the 224 subjects included in the efficacy analysis are presented in Table 7. The control dentifrice group had a mean TPI score of 3.35 while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a score of 3.33. The mean TPI scores for the two dentifrice groups after 6 and 12 weeks dentifrice use are also presented in Table 6. The control dentifrice group had a mean TPI score of 2.98 and 2.71 (6 and 12 weeks respectively), while the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group had a mean TPI score of 2.57 and 2.05 (6 and 12 weeks respectively). These TPI scores were 13.2% and 24.2% lower compared to the control dentifrice. The differences were statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Table 7.

Summary of Overall Plaque Index over time

| Time point | Mean Overall Plaque Index (±SD) | Between Treatment Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | Mean Difference (%) | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | 3.33 ± 0.326 | 3.35 ± 0.290 | |||

| Randomisation | 2.38 ± 0.450 | 2.39 ± 0.434 | |||

| Week 6 | 2.57 ± 0.330 | 2.98 ± 0.289 | −0.39 (−13.2%) | −0.45, −0.33 | <0.0001 |

| Week 12** | 2.05 ± 0.490 | 2.71 ± 0.320 | −0.65 (−24.2%) | −0.73, −0.57 | <0.0001 |

0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice vs 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride dentifrice, a negative difference favours the experimental dentifrice. Comparison based on model-adjusted means.

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

The TPI scores were separately analysed to evaluate interproximal plaque (analysis of the mesiofacial, distofacial, mesiolingual and distolingual surfaces only) this is presented in Table 8. The results for the interproximal plaque scores were similar to the overall plaque scores indicating that control of dental plaque is not present over all sites.

Table 8.

Summary of Interproximal Plaque Index over time

| Time point | Mean Interproximal Plaque Index (±SD) | Between Treatment Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%ZnCl2 (N = 112) | 0.204% Sodium Fluoride (N = 112) | Mean Difference (%) | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Pre-Prophy Baseline | 3.33 ± 0.320 | 3.35 ± 0.283 | |||

| Randomisation | 2.40 ± 0.452 | 2.40 ± 0.441 | |||

| Week 6 | 2.57 ± 0.322 | 2.97 ± 0.280 | −0.39 (−13.1%) | −0.44, −0.33 | <0.0001 |

| Week 12** | 2.05 ± 0.486 | 2.70 ± 0.313 | −0.65 (−24.0%) | −0.72, −0.57 | <0.0001 |

0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride (ZnCl2) dentifrice vs 0.204%w/w sodium fluoride dentifrice, a negative difference favours the experimental dentifrice. Comparison based on model-adjusted means.

N = 104 and N = 101 were assessed in each group respectively at Week 12.

Safety results

A total of 16 subjects reported 17 treatment emergent adverse events. There were three oral adverse events and 14 non oral adverse events, none of the adverse events were treatment related. One subject in the o-cymen-5-ol/ zinc chloride dentifrice group experienced a serious adverse event, a head injury, and was withdrawn from the study. This was not considered related to treatment.

DISCUSSION

This single centre, examiner blind, two arm, parallel group, randomised and stratified clinical study evaluated the ability of a dentifrice containing 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol and 0.6%w/w zinc chloride to maintain gingival health when used as part of an oral hygiene regimen over a 12 week period compared to a control sodium fluoride/ silica dentifrice. The study was conducted in a population with mild to moderate gingivitis typical of the general population. Results of this study indicate that the pre-experimental phase where professional dental prophylaxis and oral hygiene instruction were administered was highly effective in reducing levels of gingival inflammation and bleeding to a level of health (mean MGI and BI scores of <1.0) prior to product administration. This study design enabled assessment of the ability of the test product to maintain this level of gingival health over the test period. It is difficult to achieve the level of plaque control administered from professional prophylaxis, therefore it is not unexpected to notice that both the test and control groups showed an increase in gingival inflammation, plaque and bleeding during the study relative to the healthy state observed at randomisation after the subjects had received a complete dental prophylaxis, additional polishing and individualised toothbrush instruction. The test dentifrice containing 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol and 0.6%w/w zinc chloride maintained the level of gingival health at randomisation to a greater extent than the control dentifrice after both six and 12 weeks twice daily use. This is further illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 where the proportion of individual sites in the mouth that either increased, decreased or showed no change in MGI or BI were compared (where no change or decrease indicates maintenance of health). These results indicate that this antimicrobial activity of the formulation as reported by Pizzey9 does control dental plaque and enhance the ability of the dentifrice to maintain gingival health over the 12 week test period compared to a regular sodium fluoride dentifrice.

CONCLUSION

The results of the present clinical study demonstrate that the use of the 0.1%w/w o-cymen-5-ol/ 0.6%w/w zinc chloride dentifrice over a 12 week period provides a statistically significant benefit in maintaining gingival health compared to a regular sodium fluoride control dentifrice.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND SOURCE OF FUNDING

The work described in this manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. The authors external to GSK received no additional fee for the preparation of this manuscript. The remaining authors are employed by GSK but confirm no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–187. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindhe J, Axelsson P. The effect of controlled oral hygiene and topical fluoride application on caries and gingivitis in Swedish schoolchildren. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1973;1:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1973.tb01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindhe J, Axelsson P, Tollskog G. Effect of proper oral hygiene on gingivitis and dental caries in Swedish schoolchildren. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1975;3:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1975.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelsson P, Lindhe J. The effect of a preventative programme on dental plaque, gingivitis and caries in schoolchildren. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:126–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1974.tb01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hull PS. Chemical inhibition of plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:431–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1980.tb02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornman KS. The role of supragingival plaque in the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. A review of current concepts. J Periodont Res. 1986;21(16 Suppl):5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brading MG, Marsh PD. The oral environment: the challenge for antimicrobials in oral care products. Int Dent J. 2003;53:353–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eley BM. Antibacterial agents in the control of supragingival plaque – a review. Br Dent J. 1999;186:286–296. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzey R, Bradshaw DJ, Marquis R. Antimicrobial Effects of o-Cymen-5-ol and Zinc, alone and in combination in simple solutions and toothpaste formulations. Int Dent J. 2011;61:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baderstan A, Egelberg J, Koch G. Effect of monthly prophylaxis on caries and gingivitis in schoolchildren. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1975;3:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1975.tb00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturzenberger OP, Lehnhoff RW, Bollmer BW. A clinical procedure for determining the proficiency of gingivitis examiners. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:756–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panagakos FS, Volpe AR, Petrone, et al. Advanced oral antibacterial/anti-inflammatory technology: a comprehensive review of the clinical benefits of a triclosan/copolymer/fluoride dentifrice. J Clin Dent. 2005;16(Supplement):S1–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamster IB, Alfano MC, Seiger MC, et al. The effect of Listerine Antiseptic® on reduction of existing plaque and gingivitis. Clin Prev Dent. 1983;5:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallatt M, Mankodi S, Bauroth K, et al. A controlled 6-month clinical trial to study the effects of a stannous fluoride dentifrice on gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:762–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svatun B, Saxton CA, van der Ouderaa F, et al. The influence of a dentifrice containing a zinc salt and a non-ionic antimicrobial agent on the maintenance of gingival health. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svatun B, Saxton CA, Rolla G, et al. A 1-year study on the maintenance of gingival health by a dentifrice containing a zinc salt and non-anionic antimicrobial agent. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon JM, Lamster IB, Seiger C. Efficacy of Listerine Antiseptic in inhibiting the development of plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:697–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobene RR. A Modified Gingival Index for Use in Clinical Trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;8:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxton C, Van der Ouderara FGJ. The effect of a dentifrice containing zinc citrate & triclosan on developing gingivitis. J Periodont Res. 1989;24:75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of Vitamin C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]