Abstract

Objectives: New Zealand is a country with a relatively small population (4 million people) distributed unevenly over a relatively large land area. Adult oral health services in New Zealand are almost all delivered through a market-driven, private practice model and are funded directly by patient payments. Little attention has been given to the distribution of these services. This study reports the findings of a high-acuity examination of the distribution of private dental practices in New Zealand, using modern geographic information system (GIS) tools. Methods: A total of 1,045 private dental practices in New Zealand were geocoded. These dental practices overlaid 1,909 area units. Results: The highest practice : adult population ratios found in this study reflected the areas with the highest population densities of Maori and Pacific Islander people. Conclusions: Oral health has a substantial impact on health-related quality of life and the utilisation of dental care services can contribute to its improvement. As such, it is expected that access to care should be focused on the population groups with the highest degree of need. However, in a market-driven, mostly private practice model, such as that in New Zealand, available care is concentrated largely in areas of high socioeconomic status and in populations with lower levels of oral disease.

Key words: GIS, health service mapping, oral health, New Zealand

INTRODUCTION

New Zealand is a country with a relatively small population (4 million people) distributed unevenly over a relatively large land area (268,000 square km). As a community with close links to its local Pacific Island neighbours and historical links with the UK and Europe, New Zealand has a mixture of societal and ethnic groups. Maori people (the indigenous Polynesian population of New Zealand) represent approximately 15% of the total population1.

New Zealand has one of the healthiest populations in the world, but significant inequalities in health and oral health still exist2., 3.. Access to primary health services is a key issue for New Zealand and successive governments have focused on improving access to primary health care services4., 5..

Child oral health services are predominantly publicly funded, are delivered by dental therapists and have recently undergone a significant service planning and reinvestment programme6. By contrast, adult oral health services in New Zealand are almost all delivered through a market-driven, private practice model and are funded directly by patient payments. Little attention has been given to the distribution or accessibility of these oral health services. The majority of dentists (85%) work in the private sector and therefore most adult dental care is provided through this sector7.

However, New Zealand, like many countries, suffers a potential shortage of dental practitioners and a recognised maldistribution of dentists8 that is magnified by fundamental economic drivers that have led to the establishment of greater numbers of practices in areas of high wealth (the system is fundamentally a fee-for-service private business economic model and this drives the provision model to an uneven distribution of dental practices)9.

Although macro-scale data on dental practitioner distribution across New Zealand are available, very little detailed analysis of distribution has been undertaken. Little research has examined the distribution of dentists in relation to population data on ethnicity or socioeconomic disadvantage. This study reports the findings of a high-acuity examination of the distribution of private dental practices in New Zealand conducted using modern geographic information system (GIS) tools.

METHODS

All data were collected from open-access sources and thus no ethical approval was required.

Dental practice locations

The addresses of all dental practices in New Zealand were obtained from the Yellow Pages (telephone directory) in use in January 2011. Duplicates were removed. All addresses were then entered into a database and the longitude and latitude of each practice address were obtained through a free-access geocoding website (Google Maps). A randomly selected sample of 5% of all geocoded practices were tested against personal knowledge and other web-based information to test the integrity of the data; the confirmatory sample was found to be concordant. It is estimated that the study frameset represented a sample in excess of 95% of all New Zealand private dental practices. The study was a geographic examination of practice location and did not collect data on the number of practitioners or the working hours maintained at individual practices. These issues will be the subject of future research.

Population statistics

All population data were obtained from the most recently available New Zealand Census (2006). The geographic boundaries of each area unit (AU) were obtained from the Statistics New Zealand website1. Population data were divided by AU. Additional geographic and population data (including boundary files) for district health boards (DHBs) were obtained from the New Zealand Ministry of Health website10.

Population data were also adjusted to represent only people aged > 9 years. This adjustment was made to account for the strong level of government intervention in child dental health that would limit the number of children using private dental practices; throughout this manuscript this adjusted population is referred to as the ‘adult’ population.

All data were downloaded in January 2011.

Major cities

The longitude and latitude of the town halls in each of the three largest cities (Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch) in New Zealand were collected from Google Maps. These were used to define city limits as (for simplicity) circles of 15-km radius from each town hall. Population calculations for these city regions were based on the populations of AUs with a centroid that fell within the circle.

Socioeconomic status

The New Zealand Index of Deprivation (NZDep2006) aggregated to AU level was used as a basis of the measure of socioeconomic disadvantage. The NZDep2006 is a composite measure derived from multiple weighted socioeconomic variables collected in the 2006 NZ Census11. This index includes nine variables that either reflect or measure material and social disadvantage. NZDep2006 values were ranked into deciles ranging from one (highest deprivation) to 10 (lowest deprivation)11.

Geocoding

Geographic boundary data for each AU as obtained from Statistics NZ, the population data and socioeconomic data were geocoded using ArcGIS Version 9 [Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA]. Analysis of geographic measures was completed using the ArcGIS software and minor results tallying using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Additionally, 21 DHBs were overlaid in the mapping exercise and population data were linked to each AU. (Effective of 2010, after the DHB boundary file was produced, the two most southern DHBs were merged to form a single entity, leaving a total of 20 DHBs.)

RESULTS

A total of 1,045 private dental practices in New Zealand were geocoded. These dental practices overlaid 1,909 AUs with a total population of 4 million and an adult population (aged > 9 years) of 3.46 million people.

For all of New Zealand, the overall practice : total population and practice : adult population ratios were approximately 1 : 3,900 and 1 : 3,600, respectively.

City vs. rural distribution

Of the 1,045 dental practices mapped in New Zealand, 458 were found to be within city limits (defined by a circle with a 15-km radius extending from the town hall in each of the three largest cities). The total population within the same area amounted to 1.43 million people and 1.14 million adults. Thus, the dental practice : total population and dental practice : adult population ratios in cities were 1 : 3,100 and 1 : 2,700, respectively. The dental practice : total population and dental practice : adult population ratios in rural New Zealand were 1 : 4,800 and 1 : 3,000, respectively.

District health boards

Of the 21 DHBs, five included fewer than 20 private dental practices within the boundary, 16 included more than 20, eight included more than 50 and three included more than 100 (Figure 1). Across the 21 DHBs, the practice : total population and practice : adult population ratios ranged from 1 : 2,500 to 1 : 9,000 and from 1 : 2,200 to 1 : 7,900, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Population : practice ratios for district health boards calculated against the total population and against the population aged > 9 years.

Maori and Pacific Islander population

Area units in which Maori and Pacific Islanders (MPIs) represented ≥ 30% of the population featured only 52 dental practices. This equated to a practice : adult population ratio of 1 : 15,400. Area units in which MPIs accounted for 20–29% of the population included a total of 113 practices, giving a practice : adult population ratio of 1 : 9,100. Area units in which MPIs accounted for 10–19% of the population included 354 practices, giving a practice : adult population ratio of 1 : 4,200. Finally, in AUs in which MPIs represented < 10% of the population, the practice : adult population ratio was 1 : 250, and was thus some 61 times lower than that in AUs in which MPIs accounted for ≥ 30% of the population (Figure 2). Practice : population ratios are shown in Figure 3.

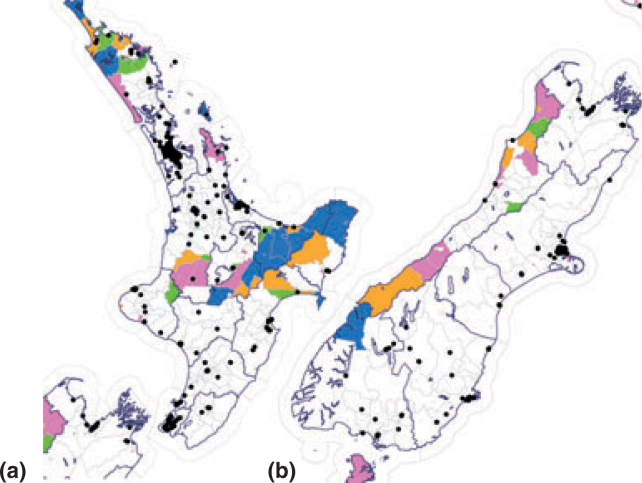

Figure 2.

Geocoding of all private practice locations in the (a) North and (b) South Islands of New Zealand and (c) in Auckland, the largest city in New Zealand. Area units (AUs) are colour-coded to show population numbers. White, population < 500; blue, population > 500. Pink, yellow and red areas indicate AUs in which Maori and Pacific Islander people account for > 10%, > 20% and > 30% of the total population, respectively. Cross-hatched areas indicate AUs in which 40% of the population is socially disadvantaged.

Figure 3.

Population : practice ratios for area units with differing percentages of Maori and Pacific Islander (MPI) people. Ratios are calculated against the total population and against the population aged > 9 years.

Social deprivation

Approximately 708,000 adults live in the wealthiest 20% of AUs in New Zealand. These areas included 234 dental practices, giving a practice : adult population ratio of 1 : 3,000 (Figure 4). The poorest 20% of AUs in New Zealand are home to some 645,000 adults and 117 dental practices, giving a practice : adult population ratio of 1 : 5,500 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Area units marked by grey boundaries on the (a) North and (b) South Islands, showing levels of socioeconomic deprivation. Blue, lowest 10%; green, next lowest 20%; orange, next lowest 30%; pink, highest 40%. Blue boundaries indicate district health board boundaries; black dots indicate dental practices.

Figure 5.

Dental practice : population ratios for each decile of the socioeconomic deprivation index in New Zealand. Ratios are calculated against the total population and against the population aged > 9 years.

DISCUSSION

These results confirm the New Zealand Dental Association’s8 assertions of a dentist maldistribution and are not inconsistent with findings in other developed countries12. The core maldistribution of dentists in city vs. rural areas was marked. Practice : adult population ratios of 1 : 2,713 in urban areas vs. 1 : 4,778 in rural areas indicate a near doubling in the paucity of provision in rural areas when measured by population only. More importantly, individuals living in rural areas face the additional issues of travel distances (and time) to reach the limited number of practices. Additionally, there is some existing awareness that many of these practices may not be fully staffed. (This is the hypothesis of future research.)

Dental disease is very significantly linked to socioeconomic deprivation13., 14., 15., 16.. Higher levels of deprivation result in higher burdens of dental disease (primarily dental caries). This is an internationally accepted finding. It is also known that Maori people have poorer oral health than non-Maori people across all age groups17. The highest practice : adult population ratios found in this study reflected the areas with the highest population densities of MPI people. For example, in AUs in which MPI people accounted for nearly a third of the population, the practice : adult population ratio was nearly 1 : 15,000 and, as the proportion of MPI people in the population decreased, the density of practices increased. For example, in AUs in which MPI people accounted for 10% of the population, the ratio fell to approximately 1 : 250.

Health care models driven by disease burden would focus care resources in areas of high need, which, in this context, would be areas of low socioeconomic status and areas with higher concentrations of Maori people. However, in New Zealand we found that practice : adult population ratios were higher in regions of high wealth.

The results of this study indicate that social inequalities exist with respect to access to and availability of private dental services when using area-based measures of socioeconomic status. It is well known that dental care use is strongly conditioned by price and income18. Most countries in the first world consistently demonstrate an income gradient in dental service utilisation19. Reliance on private financing clearly generates socioeconomic status-related inequity in utilisation (because dental practice locations are market-driven). Previous studies have also indicated that dental care utilisation is little affected by needs adjustment: richer (and insured) individuals simply use more dental services, and oral health never plays a substantial role in the concentration of utilisation18.

CONCLUSIONS

Oral health has a significant impact on health-related quality of life, and the utilisation of dental care services, especially preventive services, can contribute to the improvement of oral health. Therefore, it is expected that access to care should be focused on those groups in the population with the highest level of need. However, in a market-driven, mostly private practice model, such as that in place in New Zealand, available care is concentrated largely in areas with populations of high socioeconomic status and lower levels of oral disease.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics New Zealand . New Zealand Government; Wellington: 2001. Census of Population and Dwellings. [Google Scholar]

- 2.New Zealand Ministry of Health . MoH; Wellington: 2008. A Portrait of Health: Key results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 3.New Zealand Ministry of Health . MoH; Wellington: 2010. Our Oral Health: Key findings of the 2009 New Zealand Oral. [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Zealand Ministry of Health . MoH; Wellington: 2001. Primary Health Care Strategy. Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 5.New Zealand Ministry of Health . MoH; Wellington: 2009. Request for Expression of Interest (EOI) for the delivery of Better, Sooner, More Convenient Primary Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 6.New Zealand Ministry of Health . MoH; Wellington: 2006. Good Oral Health for All, for Life. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broadbent JM. Dental Council of New Zealand. 2008 Workforce Analysis. http://www.dentalcouncil.org.nz/dcResourcesWkfSurveys [Accessed 7 April 2011]

- 8.New Zealand Dental Association . NZDA; Auckland: 2006. NZDA Workforce Project. Final Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leake JL, Birch S. Public policy and the market for dental services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New Zealand Ministry of Health. http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf [Accessed 15 January 2011]

- 11.Salmon C, Crampton P. Department of Public Health, Wellington School of Medicine; Wellington: 2001. The NZDeP2001 Index of Deprivation. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widstrom E, Eaton KA. Oral healthcare systems in the extended European Union. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2:155–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson WM, Williams SM, Dennison PJ, et al. Were NZ’s structural changes to the welfare state in the early 1990s associated with a measurable increase in oral health inequalities among children? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson WM, Poulton R, Kruger E, et al. Socioeconomic and behavioural risk factors for tooth loss from age 18 to 26 among participants in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Caries Res. 2000;34:361–366. doi: 10.1159/000016610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamieson LM, Thomson WM. Adult oral health inequalities described using area-based and household-based socioeconomic status measures. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson WM, Poulton R, Milne BJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in oral health in childhood and adulthood in a birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broughton J. An oral health intervention for the Maori indigenous population of New Zealand: Oranga niho Maori (Maori oral health) as a component of the undergraduate dental curriculum in New Zealand. Int Dent J. 2010;60:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grignon M, Hurley J, Wang L, et al. Inequity in a market-based health system: evidence from Canada’s dental sector. Health Policy. 2010;98:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Listl S. Income-related inequalities in dental service utilisation by Europeans aged 50+ J Dent Res. 2011;90:717–723. doi: 10.1177/0022034511399907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]