Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the oral health care system in Nigeria and to outline broad policy options for strengthening the system. Methods: A critical appraisal of the oral health care system in Nigeria was conducted. The Maxwell criteria were used to assess performance. Results: There has been some progress and growth in the oral health care system in Nigeria. However, it is clear that the system falls short on many desirable attributes. The system is neither effective nor efficient and the resources available are grossly inadequate and are overstretched in many areas. The oral health care system is unresponsive to the needs of the populace and there is little stewardship of the system. Conclusions: Urgent action in the Nigerian oral health care system is required on the part of all stakeholders. The first step should involve the provision of adequate resources for the immediate implementation of the national oral health policy. There is also a need for more research on oral health-related issues in the country. Efforts towards improving the system must be properly coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Health and involve all stakeholders in the sector in order to achieve success.

Key words: Health system performance, Nigeria, oral health, oral health system

INTRODUCTION

Globally, oral health problems are regarded as a public health issue that warrants greater focus because, although poor oral health is not life-threatening, it reduces the overall health and productivity of affected persons1., 2.. Ultimately, poor oral health may have a negative impact across society if it is unchecked. Important factors influencing the oral health status of any population are the organisation and management of the oral health care system.

Oral health care systems are defined as: ‘…the combination of organisations’ flows of finance, workforce training and structure, laws, regulations and accepted practice which are aimed at improving the oral health of individuals and the community.’3 The ultimate outcome of any oral health care system is accepted as good oral health status; intermediate outcomes refer to associated oral health behaviours3. However, these outcomes do not derive from the oral health care system alone, but are influenced by other factors, such as the overall health care system and the societal value system4. Developing countries such as Nigeria do not usually maintain a separate system for oral health care, and research, administration and policy function in most oral health circles are often limited. Many developing oral health care systems emphasise the relief of orofacial pain and dental emergencies, leaving a large proportion of their population to suffer neglect5. There are suggestions that this approach to managing oral health has resulted in lower standards of care5 and consequently poor oral health in people in developing countries. Despite the wealth of information on health care systems, analyses of oral health care systems are relatively uncommon6, especially in developing countries such as Nigeria.

A thorough understanding of oral health care systems is required to provide information for policy and system development. In order to understand good or poor performance, it is vital to analyse the way the system carries out its different functions. Such assessments will identify weaknesses and areas in which changes are required in order to ensure that the system is effective and efficient. These changes will enhance the system’s ability to achieve good oral health as a component of good overall health in the population. The objective of this study was therefore to conduct a critical appraisal of the oral health care system in Nigeria with a view to assessing its strengths and weaknesses, and opportunities and threats affecting the achievement of good oral health in Nigerians. The study also sought to proffer policy options for strengthening the oral health care system in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study methodology involved a review of articles published in peer-reviewed journals, documents from international agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Internet resources and Nigerian government documents that provide insight into the oral health care system in Nigeria. The first strategy employed was to search Nigerian government publications and gazettes for relevant information. Searches were also made of the websites of organisations such as the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) (http://www.fmh.gov.ng), the WHO (http://www.who.int/) and the World Federation of Dentists (FDI) (http://www.fdiwordldental.org). Secondly, we searched the PubMed and Global Health electronic databases for relevant articles using search terms such as ‘oral health’, ‘health systems’, ‘developing countries’ and ‘Nigeria’. Where appropriate, the ‘related articles’ search tool was used to retrieve more relevant materials. Inclusion criteria applied to articles for this review referred to the objectives of the study concerned and the quality of the published material. Materials were included only if they clearly addressed issues related to the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats associated with the Nigerian health care system.

Thirdly, we checked the reference lists of all documents and articles retrieved in the previous search strategies to identify relevant materials. Further information was sourced from oral interviews of key informants in the FMoH and the National Dental Association using a structured interview format as a guide in order to reduce bias. Lastly, we used the generic search engine Scirus to source additional information as necessary. In order to ensure the validity and reliability of the information obtained, we examined the information for consistency and whenever possible verified it by triangulating it with data in other documents. Information that could not be fully substantiated was excluded. Two of the present authors (OOS and AAA) each have over 15 years of experience as dentists in Nigeria, over 10 years of experience as well as specialist training in dental public health, and previous research experience in Nigerian oral health issues, and thus provided useful insights in the analysis of key issues for this article. The third author (RVK) is a UK expert in health systems analysis and provided objectivity in conducting the system analysis.

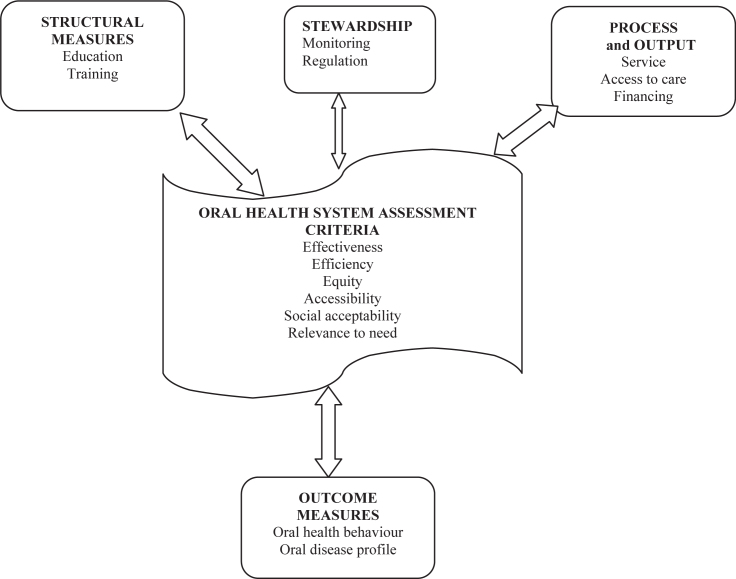

In assessing the organisation of the oral health care system, we adopted two frameworks. The first framework, suggested by Beazoglou6, examines measures related to structure (education and training), process (services and access) and outcome (oral health status). The second framework refers to the criteria described by Maxwell7, which we used to evaluate the quality of the oral health care system; these criteria refer to efficiency, effectiveness, accessibility, equity, social acceptability and relevance to need. Our assessment of the oral health care systems, as outlined in Figure 1, was therefore informed by an assessment of the structural, stewardship, and process and output measures as inputs into the system. We examined these inputs based on the quality criteria defined here to assess the outcomes of the system.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of oral health care system assessment.

RESULTS

Nigeria is the third largest and most populous country in Africa; it has a total area of 923,768 km2 and a population exceeding 140 million people. The government is a three-tier federal structure comprising a federal government, 36 state governments, and 774 local government administrations. The country is also divided into six geopolitical zones for administrative purposes8. Like many other countries, the principal goal of the Nigerian health care system is the improvement of the health status of the population9., 10.. The primary health care approach has been adopted as the key cornerstone to achieving this goal.

The Nigerian oral health care system

The oral health care system in Nigeria exists as a component of the entire health care system. As in most developing countries, the oral health care system is not clearly defined, and oral health is considered less important than other aspects of health. Consequently, it is not recognised as deserving of dedicated attention. The lack of a coordinated system for collecting health data (including on oral health) in the country makes an accurate assessment of the oral health care system difficult. In addition, there was no clear oral health policy in the country until recently, when the first national oral health policy was adopted11., 12.. This policy, alongside a previous draft, was utilised in this appraisal. In assessing the structure and organisation of the oral health care system, we include an assessment of the goals as well as the stewardship role of the system. This will be followed by evaluations using Beazoglou’s framework6 and Maxwell’s criteria7 (Figure 1). We will outline the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats associated with the oral health care system under the domains of structural, process and outcome measures.

Goals and stewardship of the oral health care system

According to the oral health policy, the goal of the oral health care system is to seek an improvement in the health status of the populace through the full integration of oral health care with general health care based on the concept of primary health care11., 12.. Stewardship of the system is provided by the FMoH through its Division of Dentistry (a subdivision of the Department of Hospital Services). The division is responsible for regulating, planning and monitoring functions for the system.

Other stakeholders in the oral health care sector include associations representing the different groups of oral health professionals in the country, such as the Nigerian Dental Association, the Nigerian Dental Therapists Board and the National Association for Dental Technologists. These groups are involved in advocacy for oral health in the country and have been actively involved in the oral health policy development process. Decisions within the oral health care system are also influenced by other health and health-related policy documents of the federal government of Nigeria, such as the National Health Insurance Policy, the National Strategic Plan and the National Health Strategic Development Plan.

In line with the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the oral health system has identified various groups, such as mothers and children, and persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), as important targets in the delivery of oral health care services. Primary oral health care has been identified as a suitable path for reaching the most vulnerable groups in the country. As a result of medical dominance of the Nigerian health care sector, in which the dentist : medical doctor ratio is 1 : 1113, the oral health care sector presently wields little influence in the decision-making processes of the health department.

Structural measures

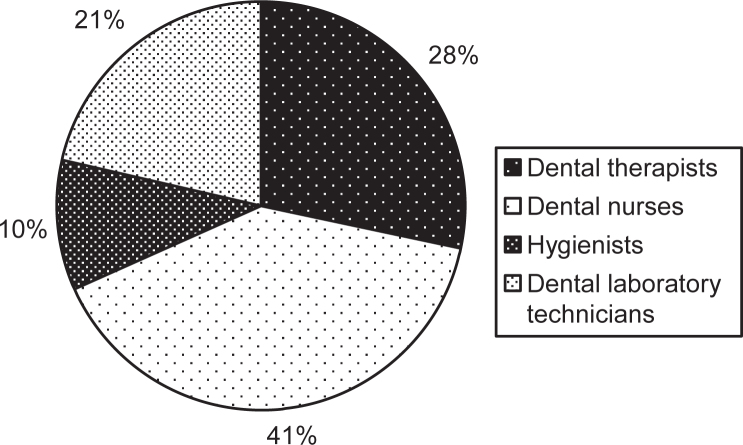

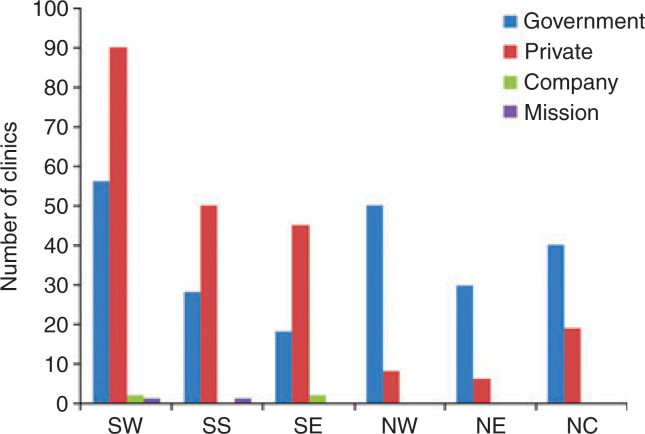

The structural measures component examines the education and training of oral health care personnel in the country. The essential human resources utilised for the provision of oral health care services in Nigeria are dental surgeons, dental nurses, dental therapists and dental laboratory technologists. Table 1 provides an overview of the oral health care human resources available in the country. Figure 2 illustrates the present mix of the oral health care workforce and Figure 3 shows the distribution of dental clinics by geopolitical zone. The majority of skilled personnel are located in the southern zones of the country, particularly in cosmopolitan cities such as Lagos and Port Harcourt.

Table 1.

Oral health care workforce in Nigeria15

| Category | Number | Workforce : population ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Dentists | 3,000 | 1 : 46,667 |

| Dental therapists | 1,100 | 1 : 127,273 |

| Dental nurses | 1,540 | 1 : 90,909 |

| Dental hygienists | 400 | 1 : 350,000 |

| Dental laboratory technicians | 830 | 1 : 168,675 |

Source: Nigerian Dental Association.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the oral health care workforce in Nigeria by profession. Source: World Health Organization15.

Figure 3.

Distribution of dental clinics in Nigeria by funding body and geopolitical/administrative zone. SW, Southwest Zone; SS, South-South Zone; SE, Southeast Zone; NW, Northwest Zone; NE, Northeast Zone; NC, North Central Zone.

Dental training is extensive; it requires a minimum of 5 years to obtain a basic degree and an additional 5 years to specialise in any aspect of dentistry. The curriculum is based on that used in developed countries, especially the USA and the UK. Dental education in Nigeria has evolved and there has been some growth in terms of the number of dental schools and their curricular content. All of the institutions accredited for dental training are government-owned and most are located in the southern part of the country (five of six institutions). Most oral health-related research is conducted at these institutions14. There are two training institutions for dental therapists, located in the Southeast and Northwest Zones, respectively. Dental technicians are trained in schools of dental technology located in all zones, except the Northeast Zone. There are also three accredited institutions for training dental nurses, all of which are located in the Southwest Zone.

In order to improve structural outcomes in the oral health care system, the quantity and quality of dentists emerging from the training system must be considered. Nigeria has been identified as having a critical shortage of health care personnel, which is worse in the oral health sector15. The yearly output of dental professionals from the six dental schools combined, which averages 100 dentists per year, is too low to meet the therapeutic and preventive needs of dental patients in Nigeria16., 17.. The number of training facilities is inadequate to meet the oral health needs of the population and their geographical distribution does not promote the equitable distribution of personnel12. There is also inadequate regulation and monitoring of these training institutions. These shortages are compounded by the fact that a large proportion of health (including dental) professionals have migrated to other countries, especially developed countries15, and others still have moved to more financially rewarding professions. The existing distribution of the workforce is inimical to the promotion of good oral health. Ogunbodede16 has suggested that the dentist : population ratio should be lower than the present ratio, but that the proportion of the dental workforce represented by dental auxiliaries (currently 57%)15 should be higher in order to achieve good oral health among Nigerians.

Process measures

Service provision

Oral health services are delivered in all three of the health care levels currently in existence in Nigeria. At the primary level, oral health care focuses on the prevention and management of dental emergencies, but services are provided at only a few primary health care centres (PHCCs) nationwide. Most secondary care involves the treatment of oral disorders and is provided at private dental clinics, general hospitals, institutions run by faith-based organisations, federal medical centres and armed forces hospitals. Tertiary oral health care is provided at teaching hospitals, in which patients receive specialised care including the treatment of oral diseases and rehabilitation for resulting deformities. Currently, most oral health services in the country are directed towards the provision of curative and rehabilitative care (i.e. secondary and tertiary health care). Traditional oral health workers are also available in rural areas, but there is presently no information on the number available and the scope of their practice. A few non-governmental organisations are also involved in the provision and promotion of oral health care in Nigeria12., 17..

There has been an increase in the number of dental facilities in the country, in both the public and private sectors, and services have been extended to previously underserved areas in the last decade. Nonetheless, the general consensus is that the oral health facilities available and their distribution are inadequate to meet the needs of the people12. It is also pertinent to note that most of the materials and equipment required for the provision of oral health care are not produced locally and are therefore expensive to procure. Moreover, the technical support required for the maintenance of these facilities is not readily available.

Access to oral health care

A total of 446 dental clinics presently provide oral health care services across the country. The management of these facilities is influenced by their funding lines, which may derive from government (federal or state), private, corporate or faith-based bodies. More than half of these facilities are located in the southern part of the country (Figure 3)14. About 50% of providers in the southern zones belong to the private sector, and about 50% of private providers are based in Lagos State alone. The majority of dental facilities are located in cities and towns because access to social amenities such as electricity and potable water is easier in urban areas. Only 20% of dentists in both the private and public sectors work in rural areas, where more than half of the population reside16. This limits the oral health care sector’s ability to provide public oral health care to a sizable proportion of the population.

The establishment of oral health facilities is usually based on the need of the community and the availability of government funding. Interestingly, very few PHCCs provide oral health services nationwide18. The cost of dental treatment in Nigeria is lower than in most developed countries, although it is still considered expensive by a large proportion of the populace. To reduce financial barriers to care, some state governments provide oral health services to the public at subsidised rates. Hence, dental care is substantially cheaper in the public sector. In addition, some state governments provide free preventive care, such as scaling and polishing treatments and extractions, to vulnerable population groups (i.e. children and elderly citizens).

Financing

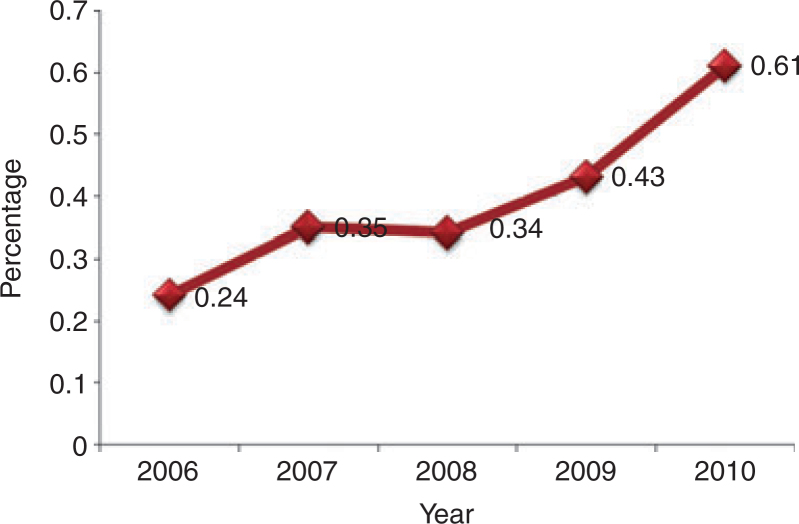

Funding for oral health care in the public sector derives from allocations by the FMoH, the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), private insurance schemes and out-of-pocket payments. The private sector is funded mainly by out-of-pocket payments and private health insurance. Budgetary allocations to health care are usually low (≤ 5% of the national budget19) and consequent competition for scarce funds, along with the over-riding attention garnered by major killer diseases such as malaria, malnutrition and HIV/AIDS, relegates apparently less pressing issues such as oral health care to the background. Figure 4 shows the proportion of health funding allocated to oral health during the 5 years to 2010. Only a tiny proportion of total spending on health (average: 0.41%) was allocated to oral health during 2006–201020. Most of these funds were directed towards the procurement of dental materials for dental facilities managed by the federal government. A similar scenario exists at the state level of care.

Figure 4.

Percentage of the national health budget allocated to oral health care in Nigeria during 2006–2010.

Direct user fees are charged for dental services in both the private and public sectors, although fees in the public sector are lower. The NHIS, introduced in 2005, is expected to provide additional funding for health care and, to a limited extent, oral health care21. Private health insurance schemes, which include provision of oral health care, are also emerging. Nonetheless, the majority of the populace still has limited financial access to oral health care because the main method of financing oral health care services remains out-of-pocket payments20., 22..

Outcome measures

As this analysis of the health system suggests, the combined constraints of the structural, governance and process components of the system impact on the outcome of oral health in Nigerian society. These outcomes in oral health behaviour and the nation’s oral health profile are direct results of the input deficiencies of the oral health care system.

Oral health behaviour

Several studies report that oral health awareness in a large proportion of Nigerians is low and their attitudes towards dentistry are equally poor17., 23., 24., 25., 26.. In our opinion, the most important reason for the poor knowledge and attitudes among Nigerians is poor access to correct and accurate oral health information. In addition, the social norms and practices adopted by most communities, particularly in rural areas, do not promote oral health. For instance, in the southwest of the country, people are encouraged to visit traditional dental practitioners who administer corrosive mouthwashes as a means of eliminating harmful organisms in the mouth. Furthermore, oral health education has not been included in the school curriculum.

Oral disease profile

Like many other countries, dental caries and periodontal disease are the oral diseases most commonly affecting Nigerians. The last national oral health survey reported prevalence rates of 30% and > 80% for dental caries and periodontal disease, respectively26., 27.. However, the oral disease burden in the country follows a pattern of deterioration closely associated with poverty and poor economic growth. Values on the decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index indicating caries prevalence in Nigeria are very low and fall in the range of 10–20%17., 26.. Nonetheless, dental caries represents a public health concern because most carious lesions remain untreated17., 26., 27., 28., 29., 30.. Periodontal disease is prevalent and affects people in all age groups and social strata31., 32., 33.. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has also contributed to the high burden of oral disease. There are over three million HIV-infected persons in Nigeria, 40% of whom present with oral lesions34., 35.. Noma, a nutrition-related oral condition that is rarely reported in most countries, is still found in Nigeria36.

That there has been some progress in the Nigerian oral health care sector is evidenced by increases in the numbers of training facilities, oral health care personnel and dental clinics. In addition, prevalences of the two common dental diseases, dental caries and periodontal disease, have remained stable over the last decade. However, the oral health status of the average Nigerian is still suboptimal. The worrisome issue is that most of those who are affected by oral diseases do not seek care18., 22., 25., and those who do seek care delay in doing so until the disease is no longer amenable to simple therapies.

According to the Maxwell criteria7 for assessing the performance of a health system, the oral health care system in Nigeria falls short on many desirable attributes. Oral health services are neither readily available nor accessible to a large proportion of the populace, in terms of both geographical location and affordability. Fewer than 20% of Nigerians have access to oral health care services37., 38. and most of these services focus on curative rather than preventive care, which might represent a more effective tool for meeting the oral health care needs of the population. In addition, these services have limited acceptability in many social circles in the country and often the services provided do not fully match the normative needs of the population. The number of oral health care personnel available is also inadequate to meet the oral health care needs of the populace. In summary, the oral health care system is not sufficiently responsive to the needs of the populace and there is little stewardship of the system. The system is neither effective nor efficient and the resources available within the system are grossly inadequate and are overstretched in many areas.

These problems highlight the need for an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats associated with the oral health sector in order to chart a course for future action. Table 2 provides a summary of the SWOT analysis.

Table 2.

SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis of the Nigerian oral health care system

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| 1 Availability of oral health services through the public sector in all states and through the private sector in many states 2 Approximately 3000 registered dentists 3 Available capacity for training more human resources 4 The National Oral Health Policy focuses on improving access to care 5 The recently adopted Oral Health Policy focuses on the integration of oral health with other health services |

1 Low access to care because most clients have low awareness of the need for oral health care and cannot afford the cost of care 2 Inequitable distribution of the oral health care workforce 3 Inequitable distribution of available oral health care facilities 4 Absence of a regulatory body to monitor and regulate the activities of oral health care professionals |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| 1 National oral health awareness programmes sponsored by agencies such as the World Federation of Dentists (FDI) 2 More interest in oral health issues at global and national levels 3 More public than private oral health facilities 4 Primary health care facilities are available in every local government area with potential for developing public oral health services 5 More training facilities are being developed for dentistry, especially in the north of the country, where access is particularly poor 6 Provision of oral health services on the National Health Insurance Scheme 7 Training of more allied dental professionals, thus increasing the availability of middle-level oral health professionals |

1 Oral health is given low priority in the health care system 2 No clear guidelines and strategies to address oral health issues nationally 3 Lack of political will to incorporate oral health care into primary health care 4 Inadequate human and financial capacity to provide and manage oral health services 5 Lack of coordination between the oral health sector and other sectors 6 Weak leadership for oral health in the Federal Ministry of Health 7 Poor knowledge of and attitudes towards oral health 8 Poor attitudes of health workers towards the integration of oral health into general health care 9 Migration of oral health care workers to other professions and other countries 10 Meagre budgetary allocations to oral health care at all levels of governance |

DISCUSSION

The history of oral health care in Nigeria spans over 50 years and demonstrates that there has been some development and growth in terms of improved oral health status, and the development of public oral health care services and appropriate structures for the delivery of an oral health policy. However, this development and growth have been slow. Several researchers have recognised some of the problems identified in this paper and proffered probable explanations for the limited progress in the sector made so far. Although we do not claim to have exhaustively identified the problems bedevilling oral health care in Nigeria, it is our opinion that those identified herein represent great challenges to moving the oral health care system in Nigeria forward. However, this study is limited by the paucity of published data on oral health in Nigeria and limited FMoH documentation. Thus this article provides a limited assessment of the oral health care system based on the evidence available, most of which was sourced from localised descriptive studies. That the data on oral health in Nigeria are limited indicates the need for more research (particularly national studies) into oral health-related issues in the country.

In their treatise on an ideal oral health care system, Tomar and Cohen39 suggest that such a system should be consistent with the principles and policies of leading authorities on the public’s health and should incorporate the most current science on clinical and public health practice. Tomar and Cohen39 identified several attributes of an ideal oral health care system; the current structure of the oral health care system in Nigeria clearly falls short on many of these attributes. The long absence of a national oral health policy to guide activities in the oral health sector is the most probable reason for this situation. It is clear that in the past political will regarding the promotion of oral health was low, as evidenced by the meagre allocations afforded to the sector40. Therefore, the recent development and adoption of a national oral health policy are laudable and herald a new dawn in the oral health care sector. This feat is most likely the result of strong advocacy by both local and international agencies, such as the WHO, FDI and the Nigerian Dental Association. There is a need to ensure proper implementation of this policy by all stakeholders in the sector as it is likely to have a positive impact on many of the factors presently hampering the effectiveness and efficiency of the oral health care system.

In addition, the stewardship role of the Division of Dentistry at the FMoH needs to be strengthened by the deployment of more human and financial resources to the unit in order to ensure the unit provides proper oversight of functions intended to achieve the policy goals. It is therefore suggested that the unit should be assured of strong, articulate and consistent leadership and that powers concerning all national oral health-related matters should be devolved to the unit. These measures should ensure that oral health is accorded appropriate priority in the health sector and should minimise the effect of medical dominance in numbers of personnel. There is also a need for continued advocacy by all stakeholders in order to guarantee that the present interest in oral health is sustained.

Concerning the structural measures for the promotion of oral health in Nigeria, the issue of inadequate access to oral health care suggests the need to develop and use new approaches in the education and training of oral health care personnel. The first step should involve the development of more training institutions, especially in the northern part of the country, where need is high. Furthermore, there is also a need for a paradigm shift in the curriculum for dental education in Nigeria towards a more community-based, prevention-oriented and broader training which, while considering global best practices and local challenges, should address existing sociocultural barriers to care. Another challenge facing the development of the oral health care workforce concerns the consistent monitoring of oral health training institutions. There is an urgent need to develop a regulatory body in the country in the form of a general dental council to monitor and regulate the training of dentists and allied professionals, as has been done in many other countries41., 42., 43., 44.. This body should also provide a clear structure for decision making in public oral health, should be based on an adequate information system, led by a full-time dentist and include membership from all oral health allied professions.

Oral health is inextricably linked with general health1., 2.. It has been suggested that patient care would be more holistic if the oral health system were to be properly integrated into the overall health care system39. There is an urgent need to fully integrate oral health care into the Nigerian health care system. However, the attitude of medical personnel remains a threat to the practice of dentistry in Nigeria13. Doctors and other policymakers do not consider oral health important because the country bears a high burden of preventable communicable diseases. This lack of perception about oral health issues also means that medical practitioners often do not refer patients for routine oral health care, despite their access to a large proportion of the populace. Health education programmes on oral health should be conducted among all health care personnel and oral health should be incorporated into the training curricula of all future health care professionals.

In Nigeria, oral health service provision focuses primarily on treatment and very little consideration is given to the prevention of common dental diseases. Any oral health system that focuses on curative care is neither sustainable nor cost-effective because many oral diseases are preventable with simple therapies39. An ideal oral health care system should provide preventive, restorative and rehabilitative care. Thus a refocusing of service provision towards preventive care, as suggested in the oral health policy, is advocated. One method of achieving this involves using the existing primary health care system, which has been relatively successful in making health care facilities accessible to most Nigerians, as a platform from which to provide preventive oral health care45., 46.. This should make the distribution of oral health services more equitable and increase access to care. Currently, PHCCs staffed by trained personnel operate in all 774 local government areas in the nation. These personnel could be trained in the diagnosis of common oral diseases and oral health education could be provided as a component of health education activities. The current development of community dentistry specialists by postgraduate colleges may also be useful in personnel training, as well as in the planning of oral health services. This strategy will increase the number of health workers providing oral health services and simultaneously ensure that more dentists and allied professionals are available to deliver more complex oral health care services.

The issue of funding for oral health care in Nigeria must be urgently addressed as funding is an important indicator of political will40. The oral health sector presently receives < 1% of the monetary allocation to the FMoH21. Most of the money received is then utilised in sustaining clinics managed by the federal government. It is therefore not surprising that there are very few national programmes for oral health and that most of those in existence are funded by external donors. We advocate for an immediate review of the current allocation formula and an increase of the allocation to oral health to ≥ 5% of the total allocation to health. In addition, gradual disengagement of the federal government from the management of dental clinics is suggested. Furthermore, the government should focus on integrating an oral health component into all national programmes in the country. The establishment of a national oral health information system which would periodically collect and collate data on oral health in the country is essential. Information obtained would be vital for policy and planning action by the oral health unit, as well as for monitoring and evaluation of the oral health system.

One of the barriers to accessing oral health care among Nigerians is economic because of the high level of poverty in the country. The NHIS, which was developed to ameliorate this problem, is yet to live up to its billing concerning oral health, probably because oral health is considered as secondary care on the scheme47. Thus the position of oral health on the NHIS should be revised to include the provision of, at minimum, preventive oral health care as defined by the WHO using primary care as the basic package of care48.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper highlights the deficits in the Nigerian oral health care system and suggests actions that would lead to its improvement. The effects of applying criteria such as efficiency, effectiveness, accessibility, equity, social acceptability and relevance to need in planning the oral health care system are evident in the oral health and general health indices of developed countries such as the USA and the UK. This appraisal indicates the need for all stakeholders in the Nigerian oral health care system to rethink their present disposition towards the sector. All efforts towards improving the system should be properly coordinated in order to achieve success. This article has only identified the building blocks necessary for future success. Further actions should be determined by the constant monitoring and evaluation of the oral health care system.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen PE. Challenges to improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Int Dent J. 2004;6(Suppl 1):329–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE, Estupian-Day S, Ndiaye C. WHO’s action for continuous improvement in oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:642–643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R, Treasure ET, Whitehouse NH. Oral health systems in Europe. Part I: finance and entitlement to care. Community Dent Health. 1998;15:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gift HC, Andersen RM. In: Community Oral Health. 2nd ed. Pine C, Harris R, editors. Quintessence Publishing; New Malden: 2007. The principles of organisation and models of delivery of oral health care; pp. 423–454. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pack AR. Dental services and needs in developing countries. Int Dent J. 1998;48(Suppl 3):239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beazoglou T. In: Jong’s Community Dental Health. Gluck GM, Morganstein WM, editors. Mosby; St Louis, MO: 1999. An overview of the oral health system in the US; pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell R. Quality assessment in health. Br Med J. 1984;288:1470–1472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earthtrends. Poverty resource: Nigeria information page. Available from: http://earthtrends.wri.org/povlinks/country/nigeria.php.2.Accessed 10 December 2011

- 9.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 2005. National Health Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 2006. National Health Bill. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 1999. National Policy and Strategy to Achieve Oral Health for all Nigerians (draft) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 2010. National Oral Health Policy (draft) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akande OO. Dentistry and medical dominance: Nigerian perspective. Afr J Biomed Res. 2004;7:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adeleke OA. Regional Centre for Oral Health Research and Training Initiatives (RCORTI) for Africa; Jos: 2006. Report on the profile of oral (dental) health care facilities, manpower and training institutions in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2006. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogunbodede EO. Gender distribution of dentists in Nigeria 1981 to 2000. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akpata ES. Oral health in Nigeria. Int Dent J. 2004;54:361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 1999. National Health Insurance Scheme Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onoriobe UE, Adekugbe Y, Osakpamwan I. Accessibility of rural dwellers in Nigeria to dental centres. Paper presented at the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) Nigerian Division Annual Scientific Conference, 29 August–1 September 2006.

- 20.Osibogun A. Crises and challenges in the Nigerian health sector. J Community Med Prim Health Care. 2004;16:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federal Ministry of Health . FMoH; Abuja: 2011. A report of the Technical Working Group for the Development of a Road Map for the Improvement of Oral Health in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adegbembo AO. Household utilisation of dental services in Ibadan, Nigeria. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:338–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sofola OO, Agbelusi GA, Jeboda SO. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices of primary school teachers in Lagos state. Niger J Med. 2002;11:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sofola OO, Orenuga OO. A survey of the knowledge, attitude and practices of antenatal mothers in Lagos, Nigeria about the primary teeth. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2005;34:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeboda SO, Adeniyi AA, Ogunbodede EO. Assessment of preventive oral health knowledge and practices among rural and urban mothers in Lagos state. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adegbembo AO, El-Nadeef MAI, Adeyinka A. National survey of dental caries status and treatment needs in Nigeria. Int Dent J. 1995;45:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orenuga OO. Oral health status of 4–16-year-old Nigerian schoolchildren in Lagos. Niger Q J Hosp Med. 1997;7:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sofola OO, Jeboda SO, Shaba OP. Dental caries status of primary school children aged 4–16 years in southwest Nigeria. Trop Dent J. 2004;27:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adeniyi AA, Ogunbodede EO, Jeboda SO, et al. Dental caries occurrence and associated oral hygiene practices among rural and urban Nigerian pre-school children. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2009;1:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheiham A. The epidemiology of chronic periodontal disease in western Nigeria. J Periodontal Res. 1968;3:257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1968.tb01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallio P, Ainamo J. Periodontal disease, dental caries and tooth loss in two Nigerian populations. Afr Dent J. 1988;2:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheiham A, Jeboda SO. Periodontal disease in Nigeria – the problem and possible solutions. Trop Dent J. 1981;4:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taiwo OO, Okeke EN, Jalo PH, et al. Oral manifestations of HIV/AIDS in Plateau State indigenes, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2006;25:32–37. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v25i1.28242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obuekwe ON, Onunu AN. Gender and oral manifestations of HIV infection among adult Nigerians. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enwonwu CO, Falker WA, Idigbe EO, et al. Noma (cancrum oris): questions and answers. Oral Dis. 1999;5:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogunbodede EO, Oyeniyi KA, Olusile AO et al. The Ipetumodu Community Oral Health Project, Nigeria. First African and Middle East International Association for Dental Research (IADR) Federation Conference, 27–29 September 2005

- 38.Aderinokun GA. Review of a community oral health programme in Nigeria after 10 years. Afr J Biomed Res. 2000;3:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomar SL, Cohen LK. Attributes of an ideal oral health care system. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(Suppl):6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiremath SS. Rakmo Press; New Delhi: 2009. Textbook of Preventive and Community Dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basker R. General Dental Council: the first 50 years. Available from: http://www.gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/Publications/Publications/Thefirst50years_Gazetteinsert_summer06[1].pdf. Accessed 10 December 2011

- 42.General Dental Council. Our Corporate Strategy. Available from: http://www.gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/Publications/Publications/GDC%20Corporate%20Strategy%202010-14%20%28web%29.pdf. Accessed 12 January 2012

- 43.Dental Council of New Zealand. Roles and functions of the Dental Council. Available from: http://www.dentalcouncil.org.nz/dcAboutCouncil. Accessed 10 December 2011

- 44.Dental Council of India. Introduction to the Dental Council of India. Available from: http://dciindia.org/. Accessed 12 January 2012

- 45.Ogunbodede EO, Jeboda SO. Integration of oral health into existing primary health care services in Nigeria – from policy to practice. Niger Dent J. 1994;11:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osazuwa-Peters N. The Alma-Ata Declaration: an appraisal of Nigeria’s primary oral health care three decades later. Health Policy. 2011;99:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adeniyi AA, Onajole AT. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS): a survey of knowledge and opinions of Nigerian dentists in Lagos. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2010;39:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helderman WHP, Benzian H. Implementation of a Basic Package of Oral Care: towards a reorientation of dental NGOs and their volunteers. Int Dent J. 2006;56:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2006.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]