Abstract

Background: The prison population is a unique and challenging one with many health problems, including poor oral health. In a developing country like India, oral health problems of the prisoners had received scant attention. Objectives: To assess the oral health status and treatment needs of life imprisoned inmates and to know the existing oral health care facilities available in central jails of Karnataka. Materials and methodology design: Cross sectional survey Participants: A systematically selected sample of 800 life imprisoned inmates, were interviewed and examined using modified WHO oral health assessment proforma (1997). Results: The prevalence of caries was 97.5% mean Decayed Missing Filled Teeth(DMFT) was 5.26; Majority of the study population had Community Periodontal Index(CPI) score of 2, whereas 21.6% had at least one sextant with a CPI score of 4. 41.1% prisoners were severely affected with loss of attachment. 8.8% inmates had dentures. Oral sub mucous fibrosis was observed among 9.9% of prisoners. 97.4% of the subjects needed oral hygiene instruction, 87.6% needed restoration, 62.1% extraction of teeth and 32.2% needed prosthesis. Bangalore and Mysore central jail had oral health care facilities on regular basis. Conclusion: This study emphasises the need for special attention from government and voluntary organisations to improve the oral health of inmates.

Key words: Dental care, dental caries, jails, oral health status, periodontal diseases, prisoners, survey

INTRODUCTION

The prison population is unique and challenging with many health problems, including poor oral health. Dental diseases can reach epidemic proportions in the prison setting1. Many challenges exist in delivering services in the prison system, including service provision with respect to security procedures, recruitment and retention of dental staff in relation to strong demand and lucrative remuneration for dentists in private practice. There is currently no standardised system of assessment and prioritisation of the dental needs of prisoners2.

The health of prisoners is of great concern, particularly because the number of persons under the jurisdiction of correction systems, including those on probation or parole, continues to increase dramatically. It is generally acknowledged from extensive research that correctional populations are more vulnerable to a wide range of health problems, most commonly alcoholism, drug abuse, infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, mental illnesses, and psychosocial and psychiatric problems3.

Prisoners serving long-term or life sentences often experience differential treatment and worse conditions of detention relative to other categories of prisoner. Their conditions of detention, compounded by the indeterminate nature of their sentences, often have a profound sociological and psychological impact, which negates the rehabilitative purpose of punishment.

Hardly any health professionals choose to work in the prison system. A lack of health concern, facilities and expertise further deteriorates the health of inmates. This explains the reason for such limited studies conducted in the prison system, especially in India4. Several studies have reported higher prevalence of dental caries and periodontal diseases among incarcerated individuals4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16.. However, Clare5 reported a substantial reduction in the prevalence of dental caries and an improvement in periodontal health among prisoners who had served continually for 3 years in prison.

In a developing country, such as India, the oral health problems of prisoners have received little attention. As the information is sparse, the objectives of the present study were to identify the oral health problems of life-imprisoned inmates and to determine the existing oral healthcare facilities available in the central jails of Karnataka.

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional study was conducted from October 2009 to March 2010 in seven central jails of Karnataka, India, following ethical approval from the Ethical Clearance Committee of JSS Dental College and Hospital, Mysore, India. Written consent was obtained from the inmates.

Sampling

The total prison population for Karnataka in 2009 was 13,216, consisting of 12,664 (95.8%) males and 552 (4.2%) females; 3200 inmates were serving life imprisonment in seven central jails of Karnataka (2009). The sample size was calculated using the online sample size calculator, available at http://www.surveysystem.com; the sample required for a finite population of 3200, a confidence interval of three and a confidence level of 95% was 800.

For a population of 3200, the required sample was 800, i.e. 25% of the population was selected. Gender-wise there were 2880 males and 320 females, 800 (722 males and 78 females) of whom responded. The samples were selected proportionately from each jail depending on the target population (those who had been life imprisoned for at least 3 years). The sampling interval (n) was calculated by dividing the target population on the day of sampling by the sample size. All possible participants (3200) were listed and numbered. A start number was chosen at random and every fifth number was picked thereafter. If a potential participant was selected, but declined to take part, the next available number was substituted.

Training and calibration

The investigator was trained for the diagnosis of oral diseases and calibrated in the interpretation of indices under the guidance of a senior faculty member. Agreement for assessment was 90%.

Collection of data

The data collection process involved the escort of the selected prisoners in groups to the interview by two numberdaras (prisoners with good behaviour). The numberdaras offered reassurance to the participants about their anonymity. Each prisoner was individually interviewed and examined, and was asked to return to the cell block on completion of the examination. Each interview and examination lasted between 10 and 15 min.

The survey design was two-fold:

-

•

Questionnaire. The study involved the completion of a predesigned questionnaire which contained questions on general information, tobacco consumption, oral hygiene practices, imprisonment characteristics, such as sentence category and duration spent, and the availability and utilisation of dental healthcare facilities

-

•

Oral examination of inmates. The inmates were asked to sit comfortably on a chair in a well-ventilated room and clinical examination was carried out under natural light with a mouth mirror, explorer and community periodontal index (CPI) probe [American Dental Association (ADA), Type III, examination method]. Instruments had been autoclaved previously in cloth wrapping in the jail hospital, when taken to barricade cold method of sterilisation was followed, using aldehyde-free instrument disinfectant (Korsolex® AF, Bode Chemie Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) at 6% for 5 min, as no self-sealing pouches were provided. The data were recorded by the investigator on a printed Modified World Health Organization Oral Health Assessment Form (1997)17. The Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S) of Greene and Vermillion18 was used to record the oral hygiene status.

Statistical analysis

The data were then entered manually into the computer, tabulated and analysed. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 was used. The various tests used for analysis were the arithmetic mean, standard deviation, chi-squared test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and contingency coefficient. P < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant for the purpose of analysis.

RESULTS

Eight hundred prisoners were interviewed and clinical examination was performed in seven central jails of Karnataka; 90.3% were males and 9.7% were females. The mean age of the participants was 41.25 years (19–76 years), a large percentage (80.8%) were married and only 2.1% had a postgraduate education. The mean duration of imprisonment served was 6.14 years (3–15 years) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population

| Characteristics | n | Percentage | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place | |||

| Belgaum | 148 | 18.5 | |

| Bijapur | 51 | 6.4 | |

| Dharwad | 30 | 3.8 | |

| Bellary | 63 | 7.9 | |

| Bangalore | 282 | 35.2 | |

| Gulbarga | 103 | 12.8 | |

| Mysore | 121 | 15.4 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 722 | 90.3 | |

| Female | 78 | 9.7 | |

| Age groups (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 169 | 21.1 | 41.25 ± 12.25 |

| 25–34 | 267 | 33.4 | |

| 35–44 | 186 | 23.3 | |

| 45–54 | 115 | 14.4 | |

| >54 | 63 | 7.9 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | 100 | 12.5 | |

| Married | 647 | 80.8 | |

| Divorced | 22 | 2.8 | |

| Widower | 22 | 2.8 | |

| Widow | 9 | 9.1 | |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | 293 | 36.6 | |

| Primary education | 233 | 29.3 | |

| Secondary education | 166 | 20.8 | |

| PUC | 47 | 5.9 | |

| Graduate | 44 | 5.4 | |

| Postgraduate | 17 | 2.1 | |

| Length of imprisonment (years) | |||

| 3–6 | 467 | 58.4 | 6.14 ± 2.25 |

| 7–10 | 296 | 37.0 | |

| 11–15 | 37 | 4.6 | |

PUC, Pre-University Course.

Tobacco consumption

The percentage of prisoners who smoked was 72.5%, 59.1% of whom smoked ‘beedi’ (‘bidi’) (a thin South Asian cigarette filled with tobacco flake and wrapped in a tendu leaf tied with a string at one end), 7.5% cigarettes and 5.9% both beedi and cigarettes; 53.4% of prisoners chewed tobacco, 27.6% of whom were tobacco chewers and 25.8% of whom used ‘gutkha’ [a preparation of crushed areca nut (also called betel nut), tobacco, catechu, paraffin, lime and sweet or savoury flavourings]. Overall, 38.8% of prisoners both smoked and chewed tobacco (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of inmates according to tobacco habits.

Oral health-related behaviour

Sixty-one per cent of prisoners (n = 495) claimed to have visited the dentist for various dental problems. The younger age group had visited the dentist for the treatment of decay (40.4%), whereas the older age group had visited the dentist for the treatment of mobile teeth (41.3%); this association was found to be statistically very highly significant (P < 0.001) With regard to their oral hygiene practices, 66.6% used a toothbrush, 29% used a finger and 4.4% used other aids to clean their teeth.

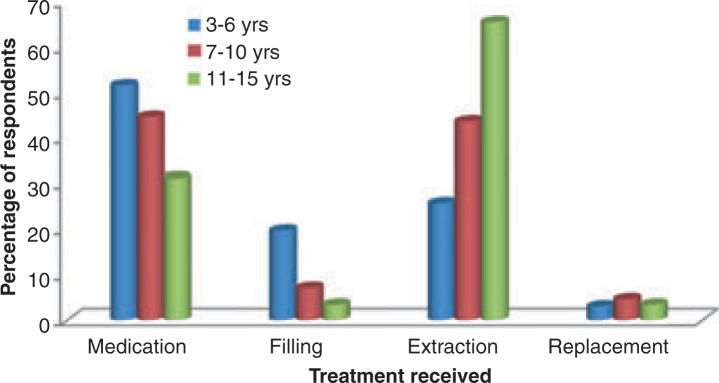

Types of dental services used

Forty-eight per cent (n = 236) used dental services for pain, swelling and infection, and only 3.6% of inmates received replacement of teeth (Figure 2). The enquiry reports of the jail superintendents revealed that Bangalore and Mysore central jails had part-time visits of dentists and permanent dental healthcare facilities for the treatment of prisoners, respectively; however, no such facilities existed in any other central jails of Karnataka.

Figure 2.

Dental treatments received by inmates according to the duration of imprisonment.

Mucosal health

A total of 20.5% of inmates had oral mucosal lesions. Among these lesions, oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) was found in 9.9% of inmates, 7% had ulcers and 1.1% had leucoplakia; the difference between healthy mucosa and affected lesions was found to be highly significant (P < 0.001). It was found that inmates of Dharwad, Gulbarga and Belgaum central jails had higher percentages of OSMF (16.7%, 14.6% and 13.5%, respectively).

Periodontal status

Despite reporting good oral hygiene practices, 66.3% of prisoners had poor oral hygiene status; 39.3% had a CPI score of two and 48.6% had a CPI score of three or four; 30.1% of prisoners had a loss of attachment (LOA) score of one or two (more than 4 mm) and 1.7% of prisoners had a score of four.

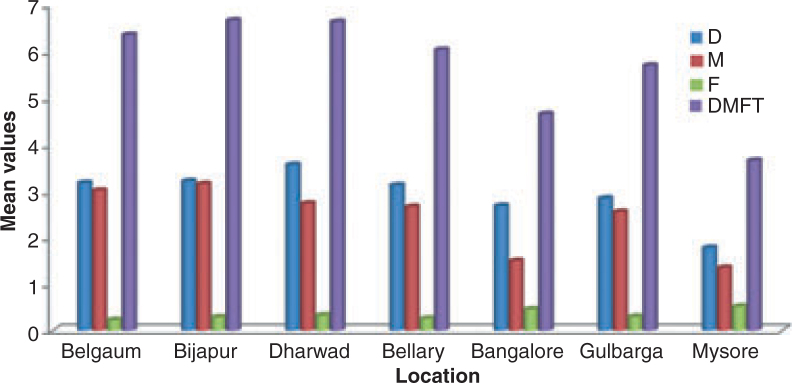

Dentition status

A total of 92.5% of prisoners had one or more untreated decayed (D) teeth, 57.1% had one or more missing (M) teeth and 24.6% had one or more filled (F) teeth. The mean DMFT score was 5.26 (± 2.91) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean number of teeth decayed (D), missing (M) and filled (F), and mean DMFT scores, among inmates.

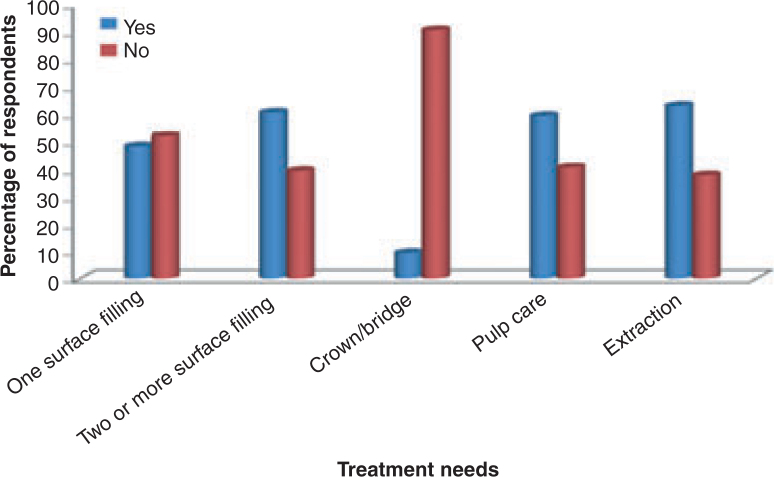

Need for treatment

A total of 48.1% of the inmates needed one surface filling, 39.5% required two or more surface fillings, 9.4% needed crown and bridge, 59.2% needed pulp care and 62.1% needed extraction (Figure 4); 97.7% of the study participants required oral hygiene instructions, 48.1% required complex periodontal treatments and 32.0% required prostheses.

Figure 4.

Number and percentages of inmates needing treatment.

Prosthetic status and needs

Among the prisoners examined, 8.8% had prostheses in the upper and lower jaws (6.6% and 2.2%, respectively). The most commonly used prosthesis was removable partial dentures. The percentage of inmates wearing prostheses was greater in the 25–34-year age group (Figure 5). Prisoners who had served imprisonment for 11–15 years had higher percentages of prosthetic need (22.8% for upper jaw and 19.6% for lower jaw) in the form of multiunit prostheses. The need for prostheses was higher for the upper arch than the lower arch.

Figure 5.

Number and percentages of inmates with prostheses by type of prosthesis.

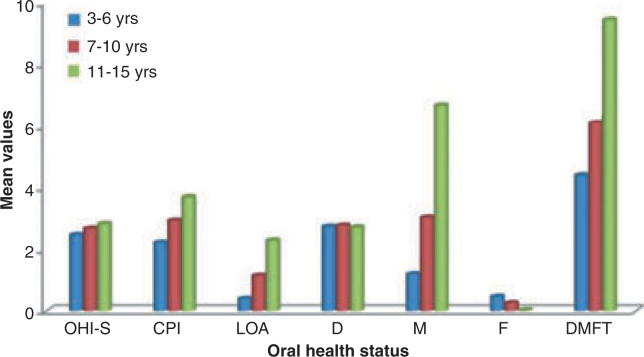

Effect of imprisonment on oral health status

The OHI-S, CPI, LOA and DMFT scores more or less increased linearly as the length of imprisonment increased, except for the mean number of decayed teeth (P > 0.05) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Oral health status of prisoners according to duration of imprisonment served. CPI, community periodontal index; D, decayed; DMFT, decayed, missing and filled teeth; F, filled; LOA, loss of attachment; M, missing; OHI-S, Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified.

DISCUSSION

The results of this cross-sectional study on life-imprisoned inmates in the central jails of Karnataka provide a unique opportunity to analyse the oral health status in this group. There have been very few studies carried out on the oral health status of prisoners. Of these, some studies6., 7., 8., 9. have reported that the oral health status of prison inmates is worse than that of the general population. The prevalence of dental caries was found to be 92.5% with a DMFT value of 5.26. Several studies3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16. have reported higher values of DMFT. This may be a result of differences in the refined diet consumption of the prisoners in the different studies.

Clare5 observed that there was a substantial reduction in dental caries among prisoners who had been in prison continuously for 3 years. The mean number of decayed surfaces was reduced from 6.7 to 3.6 (46.3% reduction). This was a result of the restoration of decayed teeth, extraction of hopeless teeth and the availability and utilisation of dental health services in prison. However, several other studies3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24. have reported an increase in decayed teeth among prisoners who have served in prison for 3 years or more. This was attributed to an ignorance about oral diseases, deleterious habits and the nonavailability of dental healthcare facilities in prison. These findings were in agreement with our study results.

We observed a large number of missing teeth. This was a result of the extraction of teeth and the fact that facilities for the conservation of teeth were not available. Both the numbers of decayed and filled teeth in females were lower in our study when compared with a report by Heng and Douglas2. Females had a significantly greater need for filling and extraction of teeth relative to males. This indicates a greater utilisation of dental health care by males than by females. The underutilisation of oral healthcare facilities by female inmates may be explained by the fact that female inmates may feel insecure in accessing a hospital area in prison which is mostly managed by male inmates; this apprehension was noted during interviews by the investigator. This area should be investigated further, so that a special recommendation can be made to the authorities.

Oral health behaviour

Our results with respect to smoking habits were in agreement with a study conducted by Dahyia and Croucher23 among male prisoners in Guragon district jail, Haryana. Some studies12., 19., 21. have reported a higher prevalence of smoked tobacco products (cigarettes) in both genders. Christina et al.24 reported a significantly higher smoking prevalence for female inmates (81%) relative to male inmates (71%).

The habit of chewing tobacco was found in 28.0% and 24.4% of male and female inmates, respectively. Together with tobacco smoking, a large number of inmates (42.8%) were habitual tobacco chewers. These results were not in agreement with a study reported by Dahyia and Croucher23, who found that only 7.3% of inmates chewed tobacco and 12.5% both smoked and chewed tobacco. Our results were not in agreement with other studies12., 21. with regard to tobacco chewing. This may be a result of differences in cultural factors in India.

Some studies12., 21. have reported higher percentages of use of alcohol and illicit drugs by prisoners. This may be a result of boredom, relief from stress, peer pressure and/or a combination of these issues. However, the present study did not evaluate the use of alcohol and illicit drugs for obvious reasons. Indian jails prohibit the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, but there have been several cases in which <1% of inmates have managed to access alcohol and illicit drugs.

Periodontal status

A total of 97.7% of inmates required oral hygiene instructions and oral prophylaxis; 48.6% of inmates required complex periodontal treatment. Similar results have been reported by Nobil3, who stated that 89.5% of inmates required at least oral hygiene instructions with extremely high needs for prophylaxis, and 19.7% required complex periodontal treatment. The reason for the fewer inmates requiring complex treatments compared with our study may be the presence of regular prison dental services in other prisons.

Oral mucosal health

A high prevalence of OSMF was observed among the inmates of Dharwad, Gulbarga and Belgaum central jails. This may be a result of the high prevalence of tobacco habits. The prevalence was also relatively high among young prisoners. This reflects the high use of tobacco chewing. Ulcers (mucocutaneous lesions) were found more commonly in older prisoners, which was in agreement with a study conducted by Pedraza et al.25 on alterations in the oral mucosa of prisoners in Mexico. It was assumed in this study that a higher tendency to use tobacco during free time was mainly a result of limited freedom of movement and the stresses of loneliness. Hence, the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions may increase with an increase in the length of imprisonment.

Dental health care received during imprisonment

A total of 53.2% of prisoners visited the dentist for dental treatment, the most common complaint being decay (34.5%); 36.7% of inmates never visited the dentist and this might have been the result of a lack of awareness. This finding was in agreement with a previous study conducted by Heidari et al.21, who found that 24% of prisoners never visited the dentist and 69% claimed to have visited the dentist. The perceived need for dental treatment was high and this may have been a result of the long waiting lists, part-time services and security reasons within the prison setting, as noted in other studies12., 15., 21., 22.. The percentage of inmates who received extraction as treatment was high and very few of these inmates received restorations. These observations disagree with a study reported by Osborn et al.15. This difference may be attributed to the regular dental services in Australian prisons compared with the part-time dental services in Karnataka prisons.

CONCLUSION

The present study was conducted on 800 life-imprisoned inmates in the central jails of Karnataka to assess their oral health status and treatment needs. It was observed that the life-imprisoned inmates who had served for longer durations showed a higher percentage of dental caries, periodontal diseases and prosthetic needs. Oral healthcare facilities were available on a regular basis for the inmates of Bangalore and Mysore central jails. This study emphasises the need for special attention from the government and voluntary organisations to meet the oral health needs of this special group. Further longitudinal studies should be conducted to explore the relationship between the onset and progression of dental diseases in the prison environment.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to the Inspector General of Police (Prison) Bangalore, Director General of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Vice Chancellor of JSS University, Principal of JSS Dental College & Hospital, Mysore, and all participants and postgraduates in our department for their kind support during this research work.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Source of support

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Grant (3/2/09/PG THESIS –MPD 16).

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey SB, Anderson AS. Reforming prison dental services in England – a guide to good practice. Health Educ J. 2005;4(Suppl):1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heng CK, Douglas EM. Dental caries experience of female inmates. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nobil CG, Fortunato L, Pavia M. Oral health status of male prisoners in Italy. Int Dent J. 2007;57:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta RK, Singh GPI, Rajhree RG. Health status of inmates in prison. Indian J Commun Med. 2001;26:2001–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clare JH. Dental health status, unmet needs and utilization of services in a cohort of adult felons at admission and after 3 years’ incarceration. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham MA, Glenn RE, Field HM. Dental disease prevalence in a prison population. J Public Health Dent. 1985;45:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salive ME, Carolla JM, Brewer TF. Dental health status of male inmates in a state prison system. J Public Health Dent. 1989;49:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1989.tb02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mixson GM, Eplee HC, Fell PH. Oral health status of a federal prison population. J Public Health Dent. 1990;50:257–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1990.tb02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badner V, Margolin R. Oral health status among women inmates at Rikers island correctional facility. J Correct Health Care. 1994;1:55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clare JH. Survey, comparison, and analysis of caries, periodontal pocket depth, and urgent treatment needs in a sample of adult felon admissions 1996. J Correct Health Care. 1998;5:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers JP. Gauging the effectiveness of a preventive dental program in a large state prison system. J Correct Health Care. 1999;6:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyer EM, Nielsen-Thompson NJ. A comparison of dental caries and tooth loss in IOWA prisoners with other prison populations and dentate US adults. Int J Dent Hyg. 2002;76:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makrides SN, Shulman JD. Dental health care of prison populations. J Correct Health Care. 2002;9:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath C. Oral health behind bars: a study of oral disease and its impact on the life quality of an older prison population. Gerodontology. 2002;19:109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2002.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborn M, Butler T, Barnard PD. Oral health status of prison inmates in New South Wales, Australia. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luann H, Morris J, Jacob A. The oral health of a group of prison inmates. Dent Update. 2003;30:135–138. doi: 10.12968/denu.2003.30.3.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . 4th edn. WHO; World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: 1997. Oral Health Survey Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green JC, Vermillion JR. The Oral Hygiene Index: a method of classifying oral hygiene status. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cropsey KL, Crews KM, Silberman SL. Relationship between smoking status and oral health in a prison population. J Correct Health Care. 2006;12:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh T. An investigation of the nature of research into dental health in prisons: a systematic review. Br Dent J. 2008;17:247–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidari E, Dickinson C, Fiske J. An investigation into the oral health status of male prisoners in the United Kingdom. J Dis Oral Health. 2008;1:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchan KM, Milsom KM, Zoiotopoulos L. The performance of a screening test for urgent dental treatment need in a prison population. Br Dent J. 2008;205:E19. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahyia M, Croucher R. Male prisoner tobacco use and oral cancer knowledge; a case study of a local prison in India. Int Dent J. 2010;60:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christina H, Stover H, Wielandt C. Scientific Institute of the German Medical Association (WIAD gem. e.V.); Bonn: 2008. Reports on Tobacco Smoking in Prison; pp. 1–36. Accessed on 24 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedraza L, Fernandez CL, Badillo RA, et al. Prisoners’ alterations of the oral mucosa in Mexico. Odonto Maxillofac. 2007;11:38–45. [Google Scholar]